Panel Members

Michael L. Boninger, MD

Panel Chair

(Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation)

University of Pittsburgh

VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System

Pittsburgh, PA

Robert L. Waters, MD

Liaison to the Consortium Steering Committee and Topic Champion

(Orthopedic Surgery)

Rancho Los Amigos Medical Center

Downey, CA

Theresa Chase, MA, ND, RN

(SCI Nursing)

Craig Hospital

Englewood, CO

Marcel P.J.M. Dijkers, PhD

(Evidence-Based Practice Methodology)

Mt. Sinai School of Medicine

New York, NY

Harris Gellman, MD

(Orthopedic Surgery)

Bascom Palmer Institute

Miami, FL

Ronald J. Gironda, PhD

(Clinical Psychology)

James A. Haley VA Medical Center

Tampa, FL

Barry Goldstein, MD

(Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation)

VA Puget Sound Health Care System

Seattle, WA

Susan Johnson-Taylor, OTR

(Occupational Therapy)

Rehabilitation Institute of Chicago

Chicago, IL

Alicia Koontz, PhD, RET

(Rehabilitation Engineering)

VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System

Pittsburgh, PA

Shari L. McDowell, PT

(Physical Therapy)

Shepherd Center

Atlanta, GA

Contributors

Consortium Member Organizations and Steering Committee Representatives

American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons

E. Byron Marsolais, MD

American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation

Michael L. Boninger, MD

American Association of Neurological Surgeons

Paul C. McCormick, MD

American Association of Spinal Cord Injury Nurses

Linda Love, RN, MS

American Association of Spinal Cord Injury Psychologists and Social Workers

Romel W. Mackelprang, DSW

American College of Emergency Physicians

William C. Dalsey, MD, FACEP

American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine

Marilyn Pires, MS, RN, CRRN-A, FAAN

American Occupational Therapy Association

Theresa Gregorio-Torres, MA, OTR

American Paraplegia Society

Lawrence C. Vogel, MD

American Physical Therapy Association

Montez Howard, PT, MEd

American Psychological Association

Donald G. Kewman, PhD, ABPP

American Spinal Injury Association

Michael M. Priebe, MD

Association of Academic Physiatrists

William O. McKinley, MD

Association of Rehabilitation Nurses

Audrey Nelson, PhD, RN

Christopher Reeve Paralysis Foundation

Samuel Maddox

Congress of Neurological Surgeons

Paul C. McCormick, MD

Insurance Rehabilitation Study Group

Louis A. Papastrat, MBA, CDMS, CCM

International Spinal Cord Society

John F. Ditunno, Jr., MD

Paralyzed Veterans of America

James W. Dudley, BSME

U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs

Margaret C. Hammond, MD

United Spinal Association

Vivian Beyda, DrPH

Expert Reviewers

American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons

Michael W. Keith, MD

MetroHealth Medical Center

American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation

David R. Gater, Jr., MD, PhD

University of Michigan/VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System

James K. Richardson, MD

University of Michigan, Department of Physical Medicine

and Rehabilitation

American Association of Spinal Cord Injury Nurses

Kathleen L. Dunn, MS, RN, CRRN-A, CNS

VA San Diego Healthcare System

Susan I. Pejoro, RN, MS, GNP

VA Palo Alto Health Care System

American Association of Spinal Cord Injury Psychologists and Social Workers

Michael Dunn, PhD

SCI Service, VA Palo Alto Health Care System

David W. Hess, PhD, ABPP

Virginia Commonwealth University

Terrie L. Price, PhD

Rehabilitation Institute of Kansas City

Marcia J. Scherer, PhD, FACRM

Institute for Matching Person and Technology, Inc.

American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine

Michal S. Atkins, OTR/L, MA

Rancho Los Amigos National Rehabilitation Center

Craig J. Newsam, DPT

Rancho Los Amigos National Rehabilitation Center

Marilyn Pires, RN, MS, CRRN-A, FAAN

Rancho Los Amigos National Rehabilitation Center

American Occupational Therapy Association

Carole Adler, BA, OTR/L

Santa Clara Valley Medical Center

Mary Shea, MA, OTR, ATP

Mt. Sinai Medical Center

Valerie Willette, OTR, CHT

American Society of Hand Therapists (ASHT)

Texas State Chapter of ASHT

American Paraplegia Society

Chester H. Ho, MD

Louis Stokes VA Medical Center

Steven Kirshblum, MD

Kessler Institute for Rehabilitation

American Physical Therapy Association

Claire E. Beekman, PT, MS, NCS

Rancho Los Amigos National Rehabilitation Center

Barbara Garrett, PT

Kessler Institute for Rehabilitation

Sharon Russo, MS, PT

Woodrow Wilson Rehabilitation Center

American Psychological Association

Lester Butt, PhD, ABPP

Craig Hospital

Donald G. Kewman, PhD, ABPP

American Psychological Association

American Spinal Injury Association

Sam C. Colachis III, MD

Ohio State University

Jennifer Hastings, PT, NCS

University of Washington

Michael Priebe, MD

Edward Hines, Jr., VA Medical Center

Association of Academic Physiatrists

Sam C. Colachis III, MD

Ohio State University

Steven Kirshblum, MD

Kessler Institute for Rehabilitation

Association of Rehabilitation Nurses

“Sis” Theuerkauf, MEd, RN, CRRN, CCM

Education and Support Consultants, Inc.

Insurance Rehabilitation Study Group

Louis A. Papastrat, MBA, CDMS, CCM

American Re Healthcare

Adam L. Seidner, MD, MPH

St. Paul Travelers Insurance Companies

James Urso, BA

St. Paul Travelers Insurance Companies

International Spinal Cord Society

Fin Biering-Sorensen, MD

Clinic for Para- and Tetraplegia,

Neuroscience Centre

Rigshospitalet Copenhagen University Hospital

Paralyzed Veterans of America

James Angelo

Kelly Saxton

United Spinal Association

Robert L. Waters, MD

Rancho Los Amigos National Rehabilitation Center

U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs

Douglas B. Barber, MD

University of Texas Health Science Center

Sunil Sabharwal, MD

VA Boston Healthcare System

Yvonne Lucero, MD

Hines VAMC/SCIS

Special Reviewers

Thomas Armstrong, PhD

University of Michigan

Richard Hughes, PhD

University of Michigan

The Consortium for Spinal Cord Medicine

Seventeen organizations, including the Paralyzed Veterans of America (PVA), joined in a consortium in June 1995 to develop clinical practice guidelines in spinal cord medicine. A steering committee governs consortium operation, leading the guideline development process, identifying topics, and selecting panels of experts for each topic. The steering committee is composed of one representative with clinical practice guideline experience from each consortium member organization. PVA provides financial resources, administrative support, and programmatic coordination of consortium activities.

After studying the processes used to develop other guidelines, the consortium steering committee unanimously agreed on a new, modified clinical/epidemiologic evidence-based model derived from the Agency for Health Care Research and Quality (AHRQ). The model is:

▪ Interdisciplinary, to reflect the varied perspectives of the spinal cord medicine practice community.

▪ Responsive, with a timeline of 12 months for completion of each set of guidelines.

▪ Reality-based, to make the best use of the time and energy of the busy clinicians who serve as panel members and field expert reviewers.

The consortium's approach to the development of evidence-based guidelines is both innovative and cost-efficient. The process recognizes the specialized needs of the national spinal cord medicine community, encourages the participation of both payer representatives and consumers with spinal cord injury, and emphasizes the use of graded evidence available in the international scientific literature.

The Consortium for Spinal Cord Medicine is unique to the clinical practice guidelines field in that it employs highly effective management strategies based on the availability of resources in the health-care community; it is coordinated by a recognized national consumer organization with a reputation for providing effective service and advocacy for people with spinal cord injury and disease; and it includes third-party and reinsurance payer organizations at every level of the development and dissemination processes. The consortium expects to initiate work on two or more topics per year, with evaluation and revision of previously completed guidelines as new research demands.

Guideline Development Process

The guideline development process adopted by the Consortium for Spinal Cord Medicine consists of 12 steps, leading to panel consensus and organizational endorsement. After the steering committee chooses a topic, a panel of experts is selected. Panel members must have demonstrated leadership in the topic area through independent scientific investigation and publication. Following a detailed explication and specification of the topic by select steering committee and panel members, consultant methodologists review the international literature, prepare evidence tables that grade and rank the quality of research, and conduct statistical meta-analyses and other specialized studies, as needed. The panel chair then assigns specific sections of the topic to the panel members based on their area of expertise. Writing begins on each component using the references and other materials furnished by the methodology support group.

After panel members complete their sections, a draft document is generated during the first full meeting of the panel. The panel incorporates new literature citations and other evidence-based information not previously available. At this point, charts, graphs, algorithms, and other visual aids, as well as a complete bibliography, are added, and the full document is sent to legal counsel for review.

After legal analysis to consider antitrust, restraint-of-trade, and health policy matters, the draft document is reviewed by clinical experts from each of the consortium organizations plus other select clinical experts and consumers. The review comments are assembled, analyzed, and entered into a database, and the document is revised to reflect the reviewers' comments. Following a second legal review, the draft document is distributed to all consortium organization governing boards. Final technical details are negotiated among the panel chair, members of the organizations' boards, and expert panelists. If substantive changes are required, the draft receives a final legal review. The document is then ready for editing, formatting, and preparation for publication.

The benefits of clinical practice guidelines for the spinal cord medicine practice community are numerous. Among the more significant applications and results are the following:

▪ Clinical practice options and care standards.

▪ Medical and health professional education and training.

▪ Building blocks for pathways and algorithms.

▪ Evaluation studies of guidelines use and outcomes.

▪ Research gap identification.

▪ Cost and policy studies for improved quantification.

▪ Primary source for consumer information and public education.

▪ Knowledge base for improved professional consensus building.

Methodology

Grading the Scientific Literature and Quantifying the Strength of the Recommendations

The methodology team affiliated with the Mt. Sinai School of Medicine conducted an extensive search of the literature, using Medline, CINAHL, Psychlit, and other bibliographic databases, using both indexed terms (MeSH terms and similar) and text words appropriate to the subject matter. Initial searches included the terms spinal (cord) injury(ies), arm(s)/hand(s)/shoulder(s)/upper limb(s), and such terms as pain, strength(en)(ing), carpal tunnel syndrome, fracture(s), ergonomic(s)(ical), wheelchair propulsion, rotator cuff. All these searches were done with indexed terms “exploded” (so as to include key terms subsumed under the search terms) and were not limited to the English language. Additional searches were performed using more specialized text words or excluding the limitation to spinal cord injury, retrieving, for instance, the literature on biomechanics and risk factors for shoulder problems in industry.

For some of the searches, the abstracts (if available) were scanned for applicability by the methodology team and the ones retained sent to all or a subgroup of the panel members. For other searches, individual panel members did the scanning for relevance. To identify additional studies, panel members used their own libraries and the reference lists of papers found through database search and otherwise.

Once the panel members had written their draft recommendations and the accompanying text providing the justification and other background information, the methodology team identified the papers and other materials (quoted or not) in support of the recommendations and submitted them to a detailed review to identify and extract the relevant evidence and evaluate the quality of the research project that was used to produce the evidence. This is a modification of the methodology used in previous consortium guidelines, in which the research design of the studies was identified and the evidence level selected (ranging from a low of V to a high of I) based on the design only (and on sample size and certainty of results in the case of randomized trials). Since Sackett published this schema in 1989, there have been many studies to show that the quality of the overall design and planned procedures, as well as the implementation of studies, affect outcomes, and evidence-based medicine textbooks now include instructions on detailed assessment of the quality of studies, based on checklists and (not uncommonly) rating scales (see West et al., 2002).

Using the recommendations in West et al., the methodology team selected the checklists of the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) (Harbour and Miller, 2001) (http://www.sign.ac.uk/) as the most appropriate and complete. SIGN offers checklists for four types of research design relevant to the present project:

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses,

Randomized controlled trials,

Cohort studies, and

Case-control studies.

Because none of these checklists was appropriate for pre-post studies, case series studies, or cross-sectional studies, all of which are commonly used in the SCI rehabilitation and outcomes literature, additional checklists were created by the team based on the template of SIGN. In addition, some items that West et al. identified as important but were missing in the SIGN checklists (e.g., mention of the funding source) were added to the seven checklists. The four modified and three supplemental checklists require the reviewer of methodology to answer questions on the internal validity, subject selection, randomization, confounding, outcomes assessment instruments, and other relevant aspects of the study being reviewed, leading to an overall assessment of the study quality as very strong (++), strong (+), or weak (−), within its category. This, in turn, leads to a conclusion whether the phenomenon reported in the paper (for instance, a change in patient status resulting from an intervention, a link between a risk factor and a particular outcome) is real or possibly an artifact of the study's methods and implementation.

Although the hierarchy of research designs described by Sackett holds true in the abstract, in practice the rankings of studies need to be adjusted downward for poor design or poor implementation of a study, and the methodology team did so based on the study quality scores. The following strength of study rating schema was used:

Systematic review (or meta-analysis) of randomized trials.

Randomized clinical trial (RCT).

Systematic review (or meta-analysis) of observational studies (case-control, prospective cohort, and similar strong designs).

Single observational study (case-control, prospective cohort, or similar strong designs).

Case series, pre-post study, cross-sectional study, or similar design.

Case study, nonsystematic review, or similar very weak design.

If on the SIGN form a study was rated “++”, it was given the number corresponding to its basic design. If it was rated “+”, it was given one level less than its nominal rank, and two levels less was assigned if the quality rating was “–”.

In addition to the grading of the clinical scientific literature reviewed for this guideline as described above, an additional grading was added to the recommendations. Support for these particular recommendations depends highly on the science of ergonomics. One definition of ergonomics is the design of equipment and work arrangements to improve working posture and ease the load on the body, thus reducing instances of long-term negative psychological and physical effects, such as repetitive strain injury and work-related musculoskeletal disorder. This science has its basis in hundreds of epidemiologic, anatomic, biomechanical, and physiologic studies. The scientific underpinning of ergonomics as it relates to upper limb repetitive strain injuries has been thoroughly reviewed in three separate review-based publications funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Institute of Medicine, and the National Research Council. In these publications separate independent panels reviewed the evidence for work relatedness of upper limb disorders and made recommendations based on the evidence. For this guideline, panel chair Michael Boninger and two special consultants, Thomas Armstrong, PhD, and Richard Hughes, PhD, reviewed the ergonomics-based recommendations and graded them based on accepted principles of the biomechanical, physiological, psychophysical, and epidemiological ergonomics literature, as well as on standard ergonomic practices, using the following scale:

Strongly agrees with scientifically validated ergonomic principles.

Somewhat agrees with scientifically validated ergonomic principles.

Not supported by scientifically validated ergonomic principles.

In each case, the ergonomic grade was reached by consensus, taking into account the differences in activities and surroundings (if any) between the industrial workers and their circumstances typically studied in ergonomics research and persons with SCI.

If there were multiple studies or multiple research traditions (clinical and ergonomic) supporting a recommendation, a next step was taken: evaluating the evidence as a whole. Evaluation of the entire body of scientific evidence supporting a particular guideline has also evolved since the 1989 Sackett proposal that consortium panels have used to date (see West et al., 2002; Harris et al., 2001). Where in the past a form of “nose counting” was used (“How many studies in support of the recommendation are there?”), the focus now is generally on the quality, quantity, and consistency of the evidence, and a number of instruments to systematize rating of the strength of the body of research (supporting a recommendation) as a whole have been published (see, for example, West et al., 2002). The methodology team used an approach based on that of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (Harris et al., 2001): The strength of the recommendation, taking into account the body of evidence overall and other factors, was rated as very strong (A), strong (B), intermediate (C), or weak (D), based on the following factors:

The number of studies and their size (the cumulative number of subjects).

The aggregate internal validity of the studies: how well a claim of a causal relationship was supported (aggregate quality of the “research design” in a narrow sense). The study strength hierarchy ratings from 1 to 6 were the major factor here.

The aggregate external validity (the representativeness of the samples studied to all persons with spinal cord injury to whom the particular recommendation applies). The SIGN checklists also provide information relevant to the issue of external validity or generalizability.

Coherence and consistency (the degree to which the findings of multiple studies were consistent, or if there were differences in findings, the degree to which the differences were plausible given variations in subjects, measures, or other relevant aspects).

The applicability of clinical research findings from studies of non-SCI groups to individuals with SCI.

The ergonomics grading.

The four levels of recommendation required the following:

LEVEL A: VERY STRONG SUPPORT FOR RECOMMENDATION

▪ Multiple strong RCTs or a single strong systematic review of RCTs, and

▪ A great majority of studies in support of the recommendation, and

▪ Studies using subjects with SCI or results clearly applicable to SCI.

LEVEL B: STRONG SUPPORT FOR RECOMMENDATION

▪ Single large, strong RCT or strong systematic review of observational studies or multiple weak RCTs or multiple strong observational studies (case control or cohort) and

▪ A majority of studies in support of the recommendation and

▪ Studies using subjects with SCI or results clearly applicable to SCI or

▪ Strong ergonomic principles support (grade 1).

LEVEL C: INTERMEDIATE SUPPORT FOR RECOMMENDATION

▪ Multiple case series, pre-post studies or weak case-control or cohort study or single weak RCT and

▪ Studies using subjects with SCI or results clearly applicable to SCI, or

▪ Studies listed under level A or B above, and

▪ Applicability of studies to SCI unclear or more than just a single study reported contrary findings, or

▪ Agreement with ergonomics literature somewhat (grade 2).

LEVEL D: WEAK SUPPORT FOR RECOMMENDATION

▪ Qualitative reviews, case studies, weak cross-sectional studies or very weak studies of other design and no ergonomic support (grade 3).

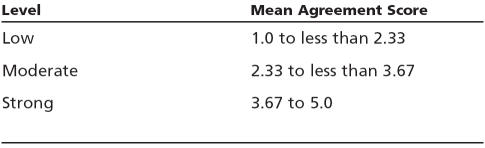

In addition, each recommendation has a “strength of panel opinion” rating. Panel members reviewed the literature, discussed recommendations among themselves and with other professional colleagues, reviewed field reviewer comments and suggestions, and based on that information and their clinical experience, independently rated each recommendation on a 1–5 scale, where 1 reflected disagreement and 5 strong agreement. The “strength of panel opinion” rating reflects the mean of the individual panel member ratings.

Levels of Panel Agreement with the Guideline Recommendation

Introduction

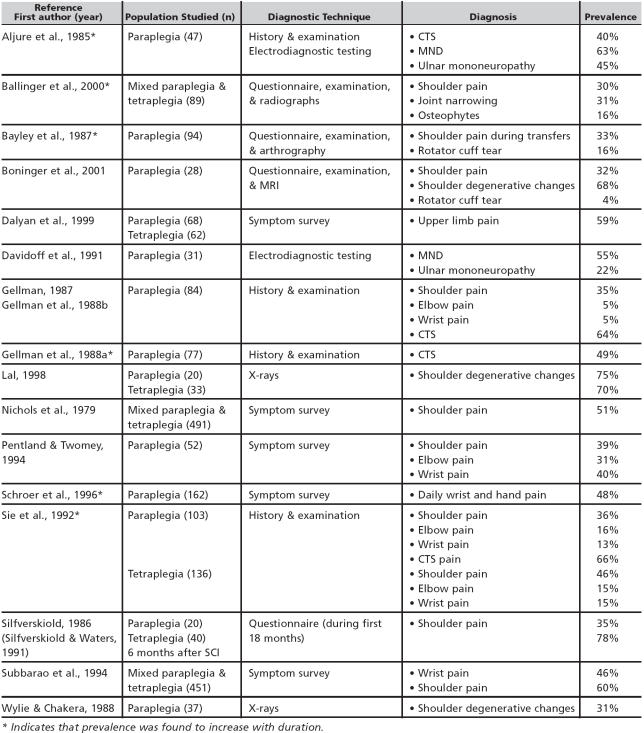

Upper limb pain and injury are highly prevalent in people with spinal cord injury (SCI), and the consequences are significant. The problems associated with upper limb pain and injury have received more attention recently as the life expectancy of individuals with SCI approaches that of the general population. Using the upper limbs for weight-bearing purposes for 40 to 50 years or more challenges limbs that are designed primarily for facilitating hand placement in several planes. The majority of studies investigating the prevalence of upper limb pain and injury has focused on two areas and diagnoses: the wrist, carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS); and the shoulder, rotator cuff disease. The results of these studies are summarized in Table 1 (page 8). This table does not include all the studies on this topic, however. In general, to be included in the table more than 20 subjects with SCI had to be studied, the population could not be restricted to athletes, and the results needed to be clearly presented.

Table 1.

Studies Documenting Prevalence of Upper Limb Injuries

Wrist and CTS

The underlying pathology behind CTS is thought to be damage to the median nerve as it passes through the carpal canal at the wrist. Therefore, researchers in this area have used both nerve conduction studies and signs and symptoms to diagnose the disorder. These primarily cross-sectional studies have found the prevalence of CTS to be between 40 percent and 66 percent. This variation in prevalence is likely due to different diagnostic criteria and different recruitment practices, which would lead to differences in the population studied. Studies have also differed in their conclusions related to the effect of length of time since SCI. As can be seen in Table 1, four studies found an association between length of time since injury and prevalence of CTS (see Table 1 footnote). In addition, some studies found median nerve damage (MND) without clinical symptoms.

Other studies have focused primarily on symptoms of pain in the hand and wrist. These studies have found the prevalence of hand and wrist pain to be between 15 percent and 48 percent. Ulnar nerve entrapment at the wrist (Guyon's canal) has also been reported. In addition to CTS and ulnar nerve injury, other diagnoses cited as causing pain include tendinitis and wrist arthritis.

Elbow

Several authors report elbow pain and injury to be a significant problem. The prevalence of elbow pain and injury has been reported to be between 5 percent and 16 percent. Although specific diagnoses are not commonly mentioned in these studies, ulnar nerve entrapment at the elbow (cubital tunnel), a common compression mononeuropathy, has been reported. The prevalence of ulnar mononeuropathy at the elbow in SCI varies between 22 percent and 45 percent. Other diagnoses commonly mentioned include lateral epicondilitis, olecranon bursitis, and arthritis.

Shoulder

The glenohumeral joint is remarkable for its lack of bony constraint. Soft tissues, such as muscles, ligaments, the capsule, and the labrum, are primarily responsible for maintaining stability and alignment. Surveys and cross-sectional studies have demonstrated that shoulder problems are common in both paraplegia and tetraplegia (between 30 percent and 60 percent). Like in CTS, the wide range in prevalence rates may be explained by differences in study populations, differences in diagnostic criteria, and inconsistency among examiners in the physical examination. Some of these studies reported on both shoulder and neck pain. Symptoms from the neck and shoulder region are often difficult to differentiate because several muscles act on both the shoulder girdle and cervical spine. Common conditions include impingement syndrome, capsulitis, osteoarthritis, recurrent dislocations, rotator cuff tear, bicipital tendinitis, and myofacial pain syndrome involving the cervical and thoracic paraspinals.

Impact of Pain

In one of the largest studies on upper limb pain, Sie et al. (1992) found that significant pain was present in 59 percent of individuals with tetraplegia and 41 percent of individuals with paraplegia. Significant pain was defined as pain requiring analgesic medication, pain associated with two or more activities of daily living, or pain severe enough to result in cessation of activity. Lundqvist et al. (1991) reported that pain was the only factor correlated with lower quality-of-life scores. Dalyan et al. (1999) determined that of individuals experiencing upper limb pain, 26 percent needed additional help with functional activities and 28 percent reported limitations of independence. In one study, individuals with SCI reported that their dependence on personal care assistants fluctuated with upper limb pain (Subbarao et al., 1994). Gerhart et al. (1993) found that upper limb pain was a major reason for functional decline in individuals with SCI who required more physical assistance since their injury. Dalyan et al. (1999) documented a significant association between employment status and upper limb pain, with unemployment higher and full-time employment lower in individuals with upper limb pain than those without (21.4 percent versus 7.1 percent and 20 percent versus 45.2 percent, respectively).

Ergonomics and Upper Limb Injury

Although the number of studies linking the activities of individuals with SCI to injury may be small, the ergonomics literature provides a strong basis for evidence-based practice. There have been three large evidence-based reviews of the link between repetitive tasks and upper limb injury. In 1997 the National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) reviewed the scientific evidence of this link (NIOSH, 1997). In 1999 the National Research Council (NRC) completed a study titled “Work-Related Musculoskeletal Disorders: A Review of the Evidence” (NRC, 1999). In 2001 the NRC, together with the Institute of Medicine, completed a review titled “Musculoskeletal Disorders and the Workplace” (NRC and IOM, 2001). These comprehensive reviews have found strong links between specific work activities and injury and all are available at the organizational Web sites (www.iom.edu and www.nas.edu/nrc). These reports have been the basis of many recommendations for worksite changes. Modification of task performance based on ergonomic analysis has been proven to reduce the incidence of pain and cumulative trauma disorders of the upper limbs in various work settings (Carson, 1994; Hoyt, 1984; Chatterjee, 1992; McKenzie et al., 1985). These same interventions can be used to prevent pain and injury in SCI.

Recommendations

1. Educate health-care providers and persons with SCI about the risk of upper limb pain and injury, the means of prevention, treatment options, and the need to maintain fitness.

(Clinical/epidemiologic evidence–None; Ergonomic evidence–None; Grade of recommendation–NA; Strength of panel opinion–Strong)

Education of individuals with SCI and clinicians is essential to the preservation of upper limb function. An educated clinician may be more likely to discuss issues of upper limb function and make appropriate recommendations. An educated patient will be more likely to follow evidence-based recommendations. Education is particularly important when lifestyle changes are suggested as a means of primary prevention.

Both the clinician and the patient should be educated about the prevalence of upper limb pain and injury, the potential impact of pain, and possible means of prevention. Well-informed patients may be more likely to recognize and act upon early signs of upper limb injury when interventions may have the greatest effect. Patient education should occur both during initial rehabilitation and at periodic evaluations.

NOTE: Recommendations in these guidelines to reduce the frequency of repetitive tasks should not be construed as advice to decrease all activity. There is evidence that suggests that more activity can prevent pain (Curtis et al., 1986). Rather, the panel's intention is to inform patients how to “move smarter” while maintaining function and fitness. The panel feels strongly that attention to an overall program of health promotion and a wellness-oriented lifestyle that includes regular activity and/or exercise is important (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 1996).

2. Routinely assess the patient's function, ergonomics, equipment, and level of pain as part of a periodic health review. This review should include evaluation of:

▪ Transfer and wheelchair propulsion techniques.

▪ Equipment (wheelchair and transfer device).

▪ Current health status.

(Clinical/epidemiologic evidence–None; Ergonomic evidence–None; Grade of recommendation–NA; Strength of panel opinion–Strong)

Medical history and physical examination provide most of the key information needed to diagnose, assess, and treat mechanical upper limb problems. The history provides much information about the pathologic processes involved and the impact of the condition on function. To address the recommendations that follow, the clinician needs to know if the patient is currently having upper limb pain.

Because most studies of individuals with SCI have demonstrated that more than half experience upper limb pain, direct questions that address not only pain, but also stiffness, swelling, locking, difficulty moving, stability, weakness, and fatigue should be asked. If a pain site is identified, it is necessary to attempt to diagnose the cause of the pain and institute treatment. The examination is essential for determining the anatomic structures involved.

In addition to assessing pain and mechanical symptoms, an assessment of the patient's risk factors for developing pain is vital. As detailed further in this guideline, many factors, such as changes in medical status, including pregnancy; new medical problems, such as heart disease; and significant changes in weight, can affect the risk of injury. Individuals who are older at the time of injury may experience functional changes sooner than people who are injured at a young age (Thompson, 1999).

Risk assessment for upper limb pain is similar to measuring serum lipids and obtaining a family history prior to initiating preventive medication for coronary artery disease. Individual items to be included in the assessment are discussed in detail in the recommendations that follow, but the basic information should include the following:

▪ Number of nonlevel transfers per day. Techniques and equipment used. Weight of the chair.

▪ Weight of the individual.

▪ Setup and propulsion technique used by manual wheelchair users.

▪ Number of overhead activities in a day.

▪ Work-related activities.

▪ Current exercise program (strengthening, stretching, and conditioning).

For both wheelchair propulsion and transfers, observation of the subject completing these activities will likely provide the most information.

Ergonomics

3. Minimize the frequency of repetitive upper limb tasks.

(Clinical/epidemiologic evidence–4/5; Ergonomic evidence–1; Grade of recommendation–B; Strength of panel opinion–Strong)

Task frequency in SCI can be minimized by decreasing the frequency of the propulsive stroke during wheelchair propulsion (see recommendations 7, 8, and 10), decreasing the number of transfers needed each day, switching to a power wheelchair when appropriate (see recommendations 6 and 34), and decreasing the frequency of other repetitive vocational and avocational tasks. This recommendation is based on the fact that a number of studies have strongly implicated frequency of task completion as a risk factor for repetitive strain injury and/or pain at the wrists (Werner et al., 1998; Silverstein et al., 1987; Loslever and Ranaivosoa, 1993; Roquelaure et al., 1997) and shoulder (Cohen and Williams, 1998; Frost et al., 2002; Andersen et al., 2002). Although the majority of studies are correlative and do not prove cause-and-effect relationships, longitudinal studies have found similar results (e.g., Fredriksson et al., 2000). These longitudinal studies provide stronger evidence of causation.

It should be noted that frequency of a task is defined differently in each study. Wheelchair propulsion, with a stroke occurring approximately once per second, would exceed what the majority of studies consider a frequent task. Adding to the strength of this recommendation is a study involving wheelchair users (Boninger et al., 1999). In this study, the health of the median nerve was related to the frequency of propulsion. The more often the individual with SCI pushed on the rim to go a constant speed, the less healthy the nerve. Median nerve injury is the basic pathology behind the development of CTS.

4. Minimize the force required to complete upper limb tasks.

(Clinical/epidemiologic evidence–5/6; Ergonomic evidence–1; Grade of recommendation–B; Strength of panel opinion–Strong)

Individuals with SCI should minimize the forces needed to complete a task. Reduced forces can be achieved by maintaining an ideal weight, improving wheelchair propulsion techniques, ensuring optimal biomechanics during weight bearing, switching to power mobility when appropriate, and minimizing exposure to high loads as part of vocational and avocational activities.

Force depends upon the position of the joint. For example, a 10-pound weight in the hand may be fine with the humerus positioned at the side of the body but would be excessive if the shoulder were abducted to 90 degrees. Higher forces are correlated with injuries and/or pain at the wrist (Roquelaure et al., 1997; Werner et al., 1998; Silverstein et al., 1987) and shoulder (Frost et al., 2002; Andersen et al., 2002). Longitudinal studies have also found that higher loads or high-force work predicts risk of development of pain or injury (Fredriksson et al., 2000; Stenlund et al., 1992 and 1993). Again it is important to note that the forces defined as high in these studies are almost always exceeded during wheelchair propulsion (Boninger et al., 1997) and are almost always exceeded during transfers and pressure relief (Reyes et al., 1995; Harvey and Crosbie, 2000; Perry et al., 1996). For example, one study defined high force as 39 Newtons (Silverstein et al., 1987) while another study related high force to lifting a tool that weighed only 1kg (Roquelaure et al., 1997). Yet another study noted that pulling or pushing a mass over 50kg was related to shoulder pain (Hoozemans et al., 2002). The average individual with SCI weighs more than 50kg (110 pounds).

The effects of high forces during wheelchair propulsion have been examined in two studies. In one study, the rate of rise of the total force applied to the pushrim was correlated with median nerve damage (Boninger et al., 1999). Higher rate of rise, which is closely related to higher force, was associated with impaired function of the median nerve. When the same subjects were followed longitudinally, decrements in median nerve function over time were predicted by the forces exerted on the pushrim at the start of the study (Fronczak et al., 2003). These results strongly suggest that higher peak forces lead to injury.

5. Minimize extreme or potentially injurious positions at all joints.

a. Avoid extreme positions of the wrist.

As much as possible, extremes of wrist motion should be avoided, particularly maximum extension when weight bearing during transfers. Awareness of extreme wrist posture is also important during vocational and avocational activities. This recommendation, which is based on ergonomic studies and research measuring pressure in the carpal canal in various positions, defines extreme positions as those near the limits of motion of the joint.

In a paper specific to wheelchair users, 18 individuals with paraplegia had manometric studies performed of their wrists in various positions (Gellman et al., 1988a). Individuals with paraplegia had higher pressures in wrist extension than control subjects without paralysis but with CTS. A number of other investigators found wrist posture in a work setting to be a risk factor for CTS (Armstrong and Chaffin, 1979; Werner et al., 1998; Hughes et al., 1997). In a recent study of wheelchair users, increased range of motion at the wrist was found to be associated with healthier median and ulnar nerves (Boninger et al., 2003). The authors explained that increased range of motion was associated with decreased forces during propulsion. The range of motion found in this study would not be considered extreme. Therefore, increased range of motion during wheelchair propulsion is acceptable, provided it is associated with decreased forces (see recommendation 10). Patients should specifically avoid repeated or sustained exertions in extreme wrist positions.

(Clinical/epidemiologic evidence–4/5; Ergonomic evidence–1; Grade of recommendation–B; Strength of panel opinion–Strong)

b. Avoid positioning the hand above the shoulder.

Individuals with spinal cord injury should avoid tasks that require the arm to be above shoulder height. This can be accomplished by modifying the home and providing appropriate assistive technology (see recommendations 14, 15, and 16).

The association between overhead activity and shoulder pain and injury in the ergonomics literature is strong. A number of studies have found that working above shoulder height increases risk of pain and injury (Pope et al., 2001; Hughes et al., 1997). In addition, this same position has been found to lead to higher forces in the shoulder (Herberts et al., 1984).

(Clinical/epidemiologic evidence–6; Ergonomic evidence–1; Grade of recommendation–B; Strength of panel opinion–Strong)

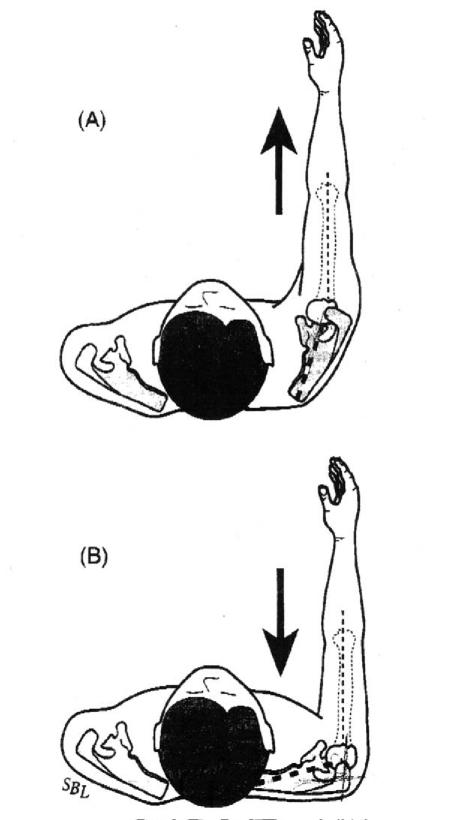

c. Avoid potentially injurious or extreme positions at the shoulder, including extreme internal rotation and abduction.

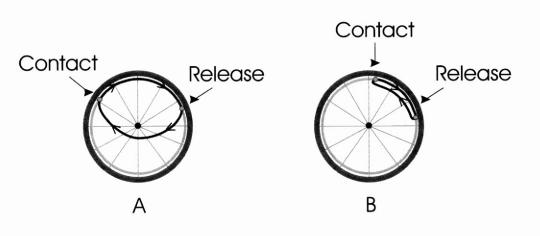

Proper positioning of the shoulder is complicated by the fact that the pectoral girdle and the humerus are so mobile. Alignment of the glenohumeral joint impacts the stability of the joint. Glenohumeral alignment refers to the relative position of the scapula to the humerus. In positions where the humerus is closely aligned with the glenoid centerline (Figure 1A), little muscular force may be needed for stability. In this position, the joint may remain stable without increasing forces because the bony alignment is stable. When the humerus is not aligned with the glenoid (Figure 1B), forceful muscular work may be needed to maintain stability of the joint. In the presence of shoulder weakness or injury, if proper alignment of the glenohumeral joint can be achieved during work, the mechanical load on soft tissues and the rotator cuff may be decreased. Although this position cannot easily be achieved during weight-bearing activities, some theorize that this relationship should be kept in mind when performing transfers and other high force tasks.

FIGURE 1. MAXIMUM SHOULDER EXTENSION.

Mechanical impingement between the humerus and overlying coracoacromial arch may lead to injury of the supraspinatus tendon. Internal rotation with abduction or forward flexion may predispose to impingement, particularly with a narrowed humeroacromial space or osteophytes from the acromioclavicular joint. The impingement test first described by Neer and later modified by Hawkins and Kennedy (1980) involves abduction and internal rotation which, if it causes pain, is considered positive and a sign of impingement syndrome. Internal rotation and abduction are common positions during wheelchair propulsion (Newsam et al., 1999; Neer II, 1983).

Maximum shoulder extension when combined with internal rotation and abduction should also be avoided. When performing such activities as transferring, adaptive equipment—a tub bench, for example—is needed to prevent awkward positions like those seen when transferring out of a tub.

(Clinical/epidemiologic evidence–4/5; Ergonomic evidence–1; Grade of recommendation–B; Strength of panel opinion–Strong)

For adequate stabilization and long-term health of the upper limb joints, proper positioning of the joint is imperative. The basis for this recommendation includes general biomechanical principles, ergonomic studies, and studies measuring the pressure in the carpal canal in various positions.

Equipment Selection, Training, and Environmental Adaptations

6. With high-risk patients, evaluate and discuss the pros and cons of changing to a power wheelchair system as a way to prevent repetitive injuries.

(Clinical/epidemiologic evidence–2/3; Ergonomic evidence–1; Grade of recommendation–B; Strength of panel opinion–Strong)

A powered form of mobility is often not considered until the individual begins to complain of upper limb pain or sustains a repetitive strain injury. Based on reviews by NRC, IOM, and NIOSH, powered mobility should help protect the upper limb by reducing repetitive forceful activity. However, use of powered mobility may lead to weight gain and upper limb deconditioning. Ultimately these factors could lead to an increased risk of injury during transfers due to the need to lift more weight by a less conditioned limb.

A person with C6 level of SCI may need powered mobility to function with peers in the community environment (Newsam et al., 1996). The advantages and disadvantages of powered mobility should be discussed initially when deciding on a wheelchair and later when replacing a wheelchair. This discussion should focus on the high prevalence of upper limb pain and injury reported among individuals with SCI as well as on the association between manual wheelchair use and upper limb injury. High-risk patients include but are not limited to those who have a prior injury to the upper limb, are obese, are elderly, or live in a challenging environment, such as on a steep hill or very rough terrain.

The advantages of power wheelchairs include:

▪ Reduced propulsion-related repetitive strain.

▪ Conserved energy and therefore reduced fatigue.

▪ Increased speed.

▪ Increased ease of traversing uneven terrain and inclines.

The disadvantages include:

▪ Decreased transportability.

▪ Increased maintenance. Increased cost.

▪ Possible weight gain.

▪ Possible decreased fitness.

Alternatives to manual mobility include scooters, power wheelchairs, and power-assist and add-on devices. Scooters provide fewer seating and control options and are less maneuverable. In addition, three-wheeled scooters are less stable than power wheelchairs.

Power-assist devices are a relatively new concept and generally consist of an add-on-powered motor(s) that supplements the force applied to the pushrim with additional rear-wheel torque. Power-assist devices have been shown to require considerably less energy expenditure to propel than a manual wheelchair (Cooper et al., 2001). Power add-on devices allow a joystick control power option on a manual wheelchair. Power add-on devices may be less expensive than other powered mobility options and are usually mounted directly onto a manual wheelchair. Power-assist and power add-on devices are lighter, less expensive, and easier to transport than the other powered options, and because these devices are often mounted directly onto a manual wheelchair, they can also be removed to allow normal manual wheelchair use.

7. Provide manual wheelchair users with SCI a high-strength, fully customizable manual wheelchair made of the lightest possible material.

(Clinical/epidemiologic evidence–2/5; Ergonomic evidence–1; Grade of recommendation–B; Strength of panel opinion–Strong)

Manual wheelchairs are generally grouped into three primary classifications in accordance with the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services K-Codes:

▪ The depot (K0001), which is designed for short-term hospital or institutional use, weighs 35 pounds or more, and is not adjustable.

▪ The lightweight (K0004), which weighs between 30 and 35 pounds and is designed with minimal adjustments.

▪ The ultralight (K0005), which weighs less than 30 pounds and is adjustable. (Note that the ultralight classification is outdated, as titanium chairs weighing less than 20 pounds are now available.)

In rare cases, an individual with SCI may require a reclining back, tilt-in space, or some other option that is only available on something other than an ultralight wheelchair. However, except in these rare instances, the panel strongly recommends that the lightest possible wheelchair be used for the following reasons.

Lighter wheelchairs require less force to propel. As stated in recommendation 4, the forces required to complete tasks should be minimized whenever possible. Rolling resistance is related to weight. Therefore, a lighter wheelchair will reduce the forces needed to propel the chair and thus the forces transmitted into the upper limb joints. One study directly compared ultralight and depot wheelchairs and found that ultralight wheelchairs allowed individuals with SCI to push at faster speeds, travel further distances, and use less energy (Beekman et al., 1999). The reduction of force will be even more important on inclines.

Lighter wheelchairs are adjustable. Only ultralight wheelchairs are adjustable to fit the user. Because rolling resistance is lower with larger diameter wheels (Brubaker, 1986), the rolling resistance will be less if the user sits further back in the chair over the larger rear wheels. Other alterations, such as customizing the rear axle position (see recommendation 8) and adjusting the camber and seat angle, are also likely to have a positive impact on propulsion mechanics.

Lighter wheelchairs are made with better components. Ultralight wheelchairs are made out of stronger, higher grade materials and better components, such as bearings that can reduce rolling resistance. Better components mean less down-time, and the result is that ultralight wheelchairs outperform both depot and lightweight-type wheelchairs when internationally accepted fatigue-testing standards are applied. Titanium chairs have a further advantage in that titanium frames dampen vibration and thus can protect the spine and shoulder from the damaging effects of vibration.

Lighter wheelchairs cost less to operate. Ultralight wheelchairs have been shown to last 13.2 times longer than depot wheelchairs and to cost about 3.5 times less to operate (Cooper et al., 1996). When compared to lightweight wheelchairs, the ultralights were found to last 4.8 times longer and were 2.3 times less expensive to operate (Cooper et al., 1997). When tested to failure, ultralight wheelchairs had the longest survival rate and had fewer catastrophic failures (Fitzgerald et al., 2001) and thus placed users at less risk for premature failure and possible injury. Although the initial cost of an ultralight chair is higher, the expense is more than made up in durability.

8. Adjust the rear axle as far forward as possible without compromising the stability of the user.

(Clinical/epidemiologic evidence–2/3; Ergonomic evidence–1; Grade of recommendation–B; Strength of panel opinion–Strong)

A more forward axle position decreases rolling resistance and therefore increases propulsion efficiency (Brubaker, 1986). A number of clinical studies support this conclusion. A more forward axle position has been found to increase the hand contact angle or amount of the pushrim used by the individual (Hughes et al., 1992). In addition, a more forward axle position has been associated with less muscle effort, smoother joint excursions, and lower stroke frequencies (Masse et al., 1992). Although the latter study involved racing wheelchair setup, positioning the seat in a low, rearward position is transferable to manual wheelchair setup. In a study of 40 wheelchair users in their own manual chairs, a more forward axle position was associated with lower peak forces, less rapid loading of the pushrim, fewer strokes to go the same speed, and greater hand contact angles (Boninger et al., 2000). Two of these parameters, stroke frequency and rate of loading the pushrim, have been associated with damage to the median nerve (Boninger et al., 1999).

Unfortunately, moving the rear axle forward has been proven to decrease rearward stability (Majaess et al., 1993). For this reason, wheelchairs are usually delivered with the axle in the most rearward position possible. As a result, it is necessary for wheelchair dealers, clinicians, and patients to adjust the setup. Antitippers can prevent rearward falls, but they also make it difficult to negotiate a curb and pop a wheelie.

Because of the effect on stability, the panel recommends that the axle be moved forward incrementally, provided the wheelchair user feels stable. Moreover, the wheelchair user needs to understand that adding weight to the chair can affect stability, and therefore packages or backpacks ideally should be located underneath the seat of the chair (Kirby et al., 1996). Finally, clinicians need to be aware that adjusting the axle position can affect wheel alignment and seat angle. Other adjustments, such as caster alignment and height, may be needed to keep the chair in good alignment.

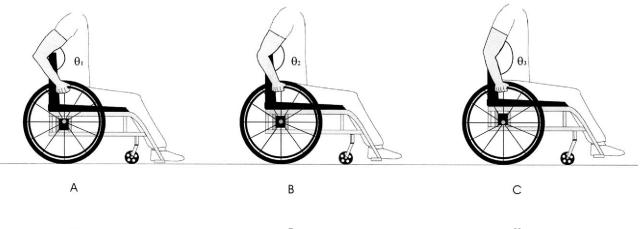

9. Position the rear axle so that when the hand is placed at the top dead-center position on the pushrim, the angle between the upper arm and forearm is between 100 and 120 degrees.

(Clinical/epidemiologic evidence–2/3; Ergonomic evidence–2; Grade of recommendation–C; Strength of panel opinion–Strong)

In general, studies have shown that a lower seat position or a higher rear axle improves propulsion biomechanics. A lower seat position has been associated with greater upper limb motions (Hughes et al., 1992; van der Woude et al., 1989), greater hand contact angles (Boninger et al., 2000; van der Woude et al., 1989), lower frequency, and higher mechanical efficiency (van der Woude et al., 1989). These findings are intuitively obvious as lower seat heights give greater access to the pushrim.

However, if the seat height is too low, the wheelchair user will be forced to push with the arm abducted, which could increase the risk for shoulder impingement. Two studies agreed that the ideal seat height is the point at which the angle between the upper arm and forearm is between 100 and 120 degrees when the hand is resting on the top dead center of the pushrim (Figure 2B) (Boninger et al., 2000; van der Woude et al., 1989). An alternative method that can be used to approximate the same position and angle is to have the individual rest with arms hanging at the side. Fingertips should be at the same level as the axle of the wheel. Adjusting seat height through vertical axle movement can affect alignment, thus other changes may be needed. Lowering the seat height also increases stability of the wheelchair.

FIGURE 2. ILLUSTRATIONS A-C SHOW DIFFERENCES IN THE ELBOW FLEXION ANGLE (Q) FROM ADJUSTING THE HEIGHT OF THE AXLE. ILLUSTRATION B DEPICTS THE RECOMMENDED ELBOW ANGLE (Q2 =100 TO 120 DEGREES). ANGLE Q1 IS SMALLER BECAUSE THE SEAT IS TOO LOW (AXLE TOO HIGH). ANGLE Q3 IS LARGER BECAUSE THE SEAT IS TOO HIGH (AXLE TOO LOW).

10. Educate the patient to:

a. Use long, smooth strokes that limit high impacts on the pushrim.

As discussed in recommendations 3 and 4, both direct and indirect evidence supports reducing peak forces, decreasing the rate of application of forces, and minimizing the frequency of propulsive strokes. A long, smooth wheelchair propulsive stroke should accomplish these goals.

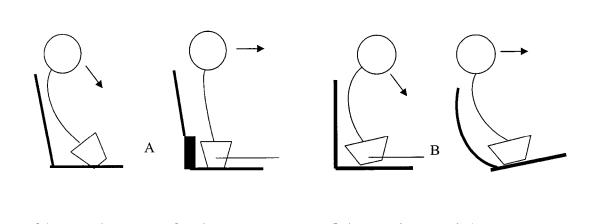

Rapid loading of the pushrim has been related to median nerve injury in both longitudinal and cross-sectional studies. When forces are applied to the pushrim in long, smooth strokes, the same amount of energy is imparted to the rim without high peak forces or a large rate of rise in forces. A long stroke, for example, as shown in Figure 3A, as opposed to a short stroke (Figure 3B), is also likely to minimize frequency or cadence.

FIGURE 3. THE RECOMMENDED PROPULSION PATTERN IS SHOWN IN “A.” AN EXAMPLE OF A POOR PROPULSION PATTERN IS SHOWN IN “B” (ARC PATTERN). THE THICK BLACK LINE ON THE WHEEL IS THE PATH FOLLOWED BY THE HAND.

(Clinical/epidemiologic evidence–5; Ergonomic evidence–1; Grade of recommendation–B; Strength of panel opinion–Strong)

b. Allow the hand to drift down naturally, keeping it below the pushrim when not in actual contact with that part of the wheelchair.

Although the path of the hand is constrained by the arc of the pushrim during the delivery of propulsive forces, there is more freedom in upper limb motion when the hand is off the rim and preparing for the next stroke. Four distinct patterns of recovery have been identified: arc, semicircular, single-looping over, and double-looping over. The single-looping over form of propulsion, which consists of having the hand above the pushrim during recovery, is the most prevalent pattern in individuals with paraplegia (Boninger et al., 2002). However, the semicircular pattern, in which the user's hand drops below the pushrim during the recovery phase, has better biomechanics (see Figure 3A). The semicircular pattern has been associated with lower stroke frequency (Boninger et al., 2002), greater time spent in the push phase relative to the recovery phase (Boninger et al., 2002), and less angular joint velocity and acceleration (Shimada et al., 1998). The semicircular pattern is preferred because the hand follows an elliptical pattern with no abrupt changes in direction and no extra hand movements.

(Clinical/epidemiologic evidence–5; Ergonomic evidence–2; Grade of recommendation–C; Strength of panel opinion–Strong)

11. Promote an appropriate seated posture and stabilization relative to balance and stability needs.

(Clinical/epidemiologic evidence–2/3; Ergonomic evidence–NA; Grade of recommendation–C; Strength of panel opinion–Strong)

Appropriate seating and trunk support provide a stable base for the upper extremities. Without a firm base of support, the arms may be at risk for injury due to the increased work necessary to compensate for instability or due to falls caused by reaching for objects. The ability to reach and complete work from a wheelchair is affected by stabilization of the pelvis and trunk (Curtis et al., 1995a; Klefbeck et al., 1996). Sitting balance is also related to level of injury, as persons with higher spinal cord injuries demonstrate less ability to reach (Lynch et al., 1998).

Age, level of injury, type of activity, and preexisting conditions guide the amount of stabilization needed. When seating an individual with SCI, the following general principles should be observed:

▪ Stabilize the pelvis first, then the lower extremities, and, last, the trunk.

▪ Stabilize the pelvis on a cushion that provides postural support as well as pressure distribution. The cushion should be mounted on a surface that maintains its position.

▪ If the individual has no fixed deformities, promote as neutral and midline a position of the pelvis as possible, and promote a midline trunk with normal lumbar and cervical lordosis.

▪ Accommodate fixed postures of the pelvis, lower extremities, and trunk to allow balance for performance of activities of daily living.

▪ Place trunk support as high as the client needs to feel stable and comfortable. Apply lateral and anterior trunk supports if the client is unable to maintain a stable posture while performing activities of daily living and other functional skills.

▪ Make special accommodations for individuals with tetraplegia, who may have a forward head posture that results in rounding of the shoulders and causes anterior instability and reliance on the upper extremities to maintain balance. Address this posture in the following ways: posterior stabilization of the pelvis in its most corrected posture (Figure 4A); accommodation of a fixed kyphosis through shape and angle in space of the back support (Figure 4B).

▪ For those individuals with C4 and higher neurologic levels, provide full support of the forearm and hand to decrease subluxation or dislocation.

FIGURE 4. “A” DEMONSTRATES HOW PROVIDING POSTERIOR PELVIC SUPPORT CAN PREVENT A KYPHOTIC POSITION OF THE TRUNK AND ANTERIOR INSTABILITY. “B” DEMONSTRATES HOW A FIXED KYPHOTIC POSTURE CAN BE ACCOMMODATED THROUGH SEAT TILT AND A CONTOURED BACKREST. THIS ACCOMMODATION PROVIDES A FUNCTIONAL POSITION.

Seating and postural support can affect both wheelchair propulsion and transfers. A high back-rest may be necessary to provide adequate trunk stabilization. The shape of the backrest must allow for scapular movement needed during wheelchair propulsion. A smaller seat-to-back angle (seat dump or squeeze) can improve pelvic stabilization but make transfers difficult. Manual wheelchair users should be provided with a lightweight cushion as increased weight increases propulsion forces (see recommendations 4 and 7). In all circumstances, the client's comfort, function, and preference are paramount. Finally, clinicians should be aware that individuals who are older at the time of injury may experience functional changes sooner than those injured at a younger age.

12. For individuals with upper limb paralysis and/or pain, appropriately position the upper limb in bed and in a mobility device. The following principles should be followed:

Avoid direct pressure on the shoulder.

Provide support to the upper limb at all points.

When the individual is supine, position the upper limb in abduction and external rotation on a regular basis.

Avoid pulling on the arm when positioning individuals.

Remember that preventing pain is a primary goal of positioning.

(Clinical/epidemiologic evidence–None; Ergonomic evidence–NA; Grade of recommendation–NA; Strength of panel opinion–Strong)

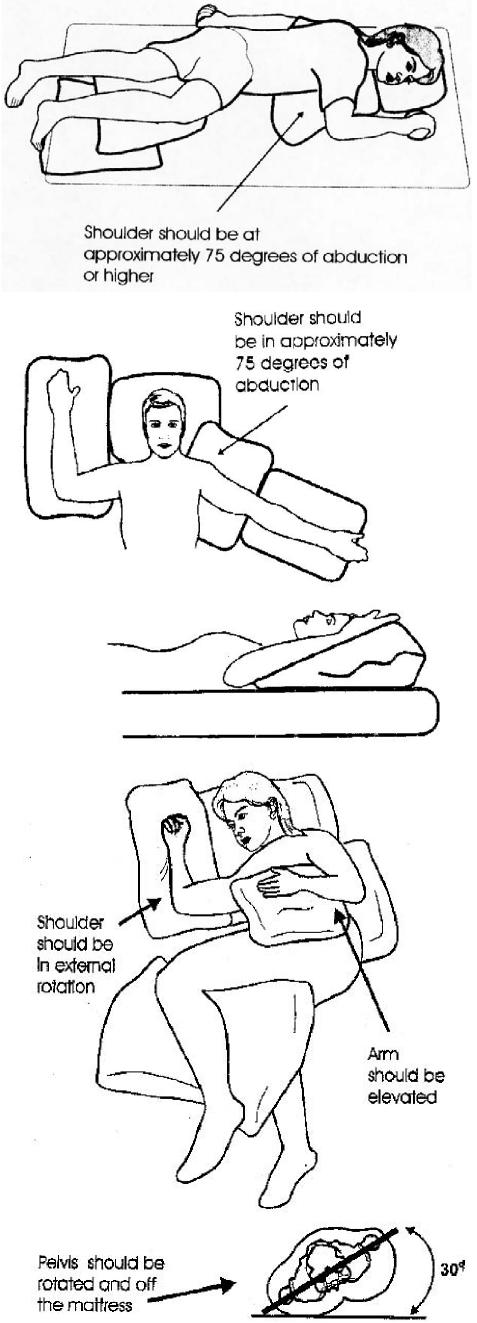

Inappropriate positioning of the shoulder when the individual is supine or sitting can lead to decreased range of motion and associated upper limb pain and injury. Individuals with tetraplegia tend to position their arms close to the body in a position of internal rotation. The abducted and externally rotated arm should be alternated between the left and right sides so that each arm spends an equal amount of time in the positions shown. To avoid pulling on the arms while positioning in bed, hold the patient at the lower portion of the scapula. The position shown in Figure 5 may also provide passive stretch and pain relief for individuals with paraplegia and shoulder pain.

FIGURE 5. EXAMPLES OF APPROPRIATE BED POSITIONING TO SUPPORT THE UPPER LIMB. (COURTESY OF RANCHO LOS AMIGOS NATIONAL REHABILITATION CENTER, DOWNEY, CALIFORNIA).

13. Provide seat elevation or possibly a standing position to individuals with SCI who use power wheelchairs and have arm function.

(Clinical/epidemiologic evidence–2/3; Ergonomic evidence–1; Grade of recommendation–B; Strength of panel opinion–Strong)

One of the strongest associations found in the 1997 NIOSH review was between shoulder and neck pain and posture. In general, posture in this context referred to overhead activity. Numerous studies have found an association between overhead activity and the development of shoulder pain (Herberts et al., 1984; Bjelle et al., 1979). In addition, a number of studies have shown that the degree of upper arm elevation is one of the most important parameters influencing shoulder muscle load (Sigholm et al., 1984; Palmerud et al., 2000; Jarvholm et al., 1991). The muscles most affected were the rotator cuff muscles. Even if modifications to both the home and work environments are so complete as to totally negate the need for overhead activities, individuals with SCI will still be forced to do them whenever they shop, visit the post office, or check out books at the library.

Another compelling reason for elevating seats is the need for level transfers. Research on transfers has shown that forces are reduced when an individual makes a level transfer or transfers downhill (Wang et al., 1994). (See recommendation 15a.) The only way to ensure this type of transfer is through seat elevation. In the past, seat elevation added seat height to the wheelchair, making transfers back into the chair more difficult and making it more difficult to fit under low surfaces such as tables. Some power wheelchairs offer seat elevation with very low seat heights, which helps to alleviate this concern.

An alternative means of reducing overhead activities is by prescribing a power wheelchair that allows individuals to stand. But standing wheelchairs may not help with transfers and may increase the risk of injury to bones, joints, and skin, all of which must be evaluated prior to the prescription.

14. Complete a thorough assessment of the patient's environment, obtain the appropriate equipment, and complete modifications to the home, ideally to ADA standards.

(Clinical/epidemiologic evidence–None; Ergonomic evidence–NA; Grade of recommendation–NA; Strength of panel opinion–Strong)

A thorough assessment of the environments where routine transfers, activities of daily living, and work are performed is necessary for consumers and clinicians to know when and where to intervene. The environment should be altered and/or equipment provided to minimize overhead activities, reduce forces in the extremities, and reduce the frequency at which activities are completed.

At a minimum, evaluation should include home, work, and school environments and the means of transportation. Every environment should be built or modified, when possible, in a manner consistent with ADA standards. If that is not possible, activities that involve raising the arm above shoulder height should be modified or avoided, or adaptive equipment should be used. For example, objects in overhead cabinets should be transferred to a lower location or a reacher should be used. In addition, the home should be modified to ensure that transfers are level (see recommendation 15a).

15. Instruct individuals with SCI who complete independent transfers to:

a. Perform level transfers when possible.

Whenever possible, the transfer surfaces should be either at equal height or downhill, as uphill transfers are known to increase forces in the upper limb (Wang et al., 1994). Clients with tetraplegia may not be able to lift their weight if greater flexion is needed at the elbow (Harvey and Crosbie, 1999), as is required in an uphill transfer. Consider adaptive bath equipment, such as roll-in shower chairs, and other adjustable height transfer surfaces that can be used for multiple tasks, such as bathing and bowel and bladder care, to be part of a prevention program.

(Clinical/epidemiologic evidence–2/3; Ergonomic evidence–2; Grade of recommendation–C; Strength of panel opinion–Strong)

b. Avoid positions of impingement when possible.

The classic position of impingement is with the arm internally rotated, forward flexed, and abducted (Neer II, 1983). In this position, the rotator cuff tendon insertions at the greater tuberosity of the humerus are in closer proximity to the undersurface of the acromioclavicular joint. In a normally functioning shoulder this will not necessarily cause impingement; however, in the presence of pain or rotator cuff impairment, impingement may occur. It is often difficult to avoid these positions during transfers.

As stated earlier, forces at the shoulder are greater with increasing flexion and abduction (Sigholm et al., 1984). When pushing down on an object with the arm at the side, forces are transmitted directly through the elbow and wrist to the shoulder (Harvey and Crosbie, 2000). Little if any movement is created at the arm in this position. If the arm is abducted or forward flexed, then, in addition to the forces, movements will also occur at the shoulder. These movements lead to higher forces in the shoulder muscles themselves. When an overhead reach is necessary for certain transfers (such as into a car or truck), minimize internal rotation of the arm.

(Clinical/epidemiologic evidence–5; Ergonomic evidence–2; Grade of recommendation–C; Strength of panel opinion–Strong)

c. Avoid placing either hand on a flat surface when a handgrip is possible during transfers.

The forces associated with transfers are borne at the wrist and hand. Applying force through an extended wrist and flat palm increases pressure in the carpal canal, thereby compressing the median nerve. A number of studies have documented the association between wrist posture and CTS, with greater flexion and extension linked to injury, more so in the presence of high forces (Tanzer, 1959; Gelberman et al., 1981; Lundborg et al., 1982; Werner et al., 1998; Roquelaure et al., 1997; Armstrong and Chaffin, 1979).

One study on the association between wrist postures and CTS specific to individuals with SCI (Gellman et al., 1988a) found that individuals with paraplegia, both with and without CTS, had higher pressures in wrist extension than unimpaired individuals with CTS. In a cadaver study, Keir et al. (1997) found that hydrostatic carpal tunnel pressure was greatest in extension and in ulnar deviation with the palmaris longus loaded. This is a common position for transfers when the hand is resting on a flat surface (Harvey and Crosbie, 2000). In addition, it has been observed that with excessive wrist extension, carpal hypermobility can occur over time (Schroer et al., 1996).

When possible, the hand should be placed in a position that allows it to avoid extremes of wrist extension (i.e., that allows the fingers to drape over and grasp the edge of the transfer surface). Transfers using closed-fist maneuvers with the wrist in neutral may reduce the pressures in the carpal tunnel; however, the impact on the metacarpal joints is unknown and this may be an unstable position for the wrist. To preserve tenodesis grip for individuals who use tenodesis, transfers should be performed with the wrist extended and the fingers flexed.

(Clinical/epidemiologic evidence–2/5; Ergonomic evidence–3; Grade of recommendation–C; Strength of panel opinion–Strong)

d. Vary the technique used and the arm that leads.

Clinical observation and electromyographic analysis of transfers in individuals with paraplegia have found that the forces and work performed with the trailing arm are greater than that of the leading arm (Perry et al., 1996). Differences were also seen between the trailing and leading arm in a study of subjects without disabilities (Papuga et al., 2002). Individuals who have difficulty performing transfers because of pain from rotator cuff tendinitis or a tear could potentially lessen the pain on the affected shoulder if they lead with their hurt arm.

A transfer technique to consider involves flexing the trunk forward over the weight-bearing arm while protracting and depressing the scapula. This position allows better transmission of the forces between the humerus and the trunk (Gagnon et al., 2003). In a forward flexed position, the vertical distance between the shoulders and buttocks is reduced (Harvey and Crosbie, 2000), which may be mechanically advantageous to the elbow extensor. In addition, in this position the rotator cuff may exhibit less activity, more weight will be borne through the glenoid, and the risk of impingement may be reduced (Gagnon et al., 2003).

When performing weight-shifting or pressure relief maneuvers, the same principles apply. Whenever possible, the person with a spinal cord injury should perform pressure relief activities by using a combination of techniques, such as forward leaning, side-to-side shifting, and depression-style maneuvers.

(Clinical/epidemiologic evidence–None; Ergonomic evidence–2; Grade of recommendation–C; Strength of panel opinion–Strong)

Evidence exists that transfers can lead to upper limb injury. In a transfer, the shoulders must not only support the weight of the body, as in a vertical weight relief raise, but also must shift the trunk mass between the outreached hands. Pressure during transfers has been shown to be 2.5 times greater than that recorded when the shoulder is not bearing weight (Bayley et al., 1987). The increase in pressure is likely due to the shift in body weight from the trunk through the clavicle and scapula and across the subacromial tissues to the humeral head. The increased pressures stress the vasculature of the rotator cuff and can contribute to tendon degeneration.

16. Consider the use of a transfer-assist device for all individuals with SCI. Strongly encourage individuals with arm pain and/or upper limb weakness to use a transfer-assist device.

(Clinical/epidemiologic evidence–2/5; Ergonomic evidence–2; Grade of recommendation–C; Strength of panel opinion–Strong)

Risk factors associated with loss of independence in terms of transfers for individuals with SCI include pain, excessive body mass and increased body fat, shoulder range-of-motion and muscle deficiencies or imbalance, poor exercise capacity, and intolerance for activities of daily living (Nyland et al., 2000). Because assistive devices have the potential to reduce forces in the upper limb during transfers, such devices may be effective at preventing and treating upper limb injuries.

Individuals with higher level spinal cord injuries place a greater demand on their muscles during transfers (Gagnon et al., 2003); use of a sliding board will reduce the amount of force needed for lateral movement (Grevelding and Bohannon, 2001). The reduction of force is even greater with friction-reducing surfaces or a disc that slides easily along the surface (Grevelding and Bohannon, 2001). Again, reduced stress should lessen the chance of injury or exacerbation of pain.

Sliding-board transfers allow the transfer motion to be broken into smaller movements, which can reduce injurious forces (Butler et al., 2000). However, sliding boards are not suitable for transfers across two surfaces that vary greatly in height (such as from a wheelchair to a truck seat or SUV). Therefore, standard transfer training without the use of a transfer-assist device is still essential for all patients who can do so safely. Difficulties can arise if the patient is large, has spasticity that interferes with a transfer, or has skin that is highly susceptible to tissue breakdown (e.g., an elderly individual with SCI or with a previous history of pressure sores).

Unfortunately, with the exception of a sliding board, transfer-assist devices are frequently not portable and can be a major inconvenience. Other transfer-assist options include patient lifts, which are available in various configurations (e.g., portable versus permanent, sling versus strap, mechanical versus electric), and power seat elevators, as specified in recommendation 13. If manual assistance is provided, care should be taken not to pull on a weak or unstable upper limb when lifting.

Other conditions that require transfer-assist devices are pregnancy and obesity. The additional weight associated with these conditions increases the forces in the shoulder during transfers, placing the individual at increased risk for injury. A large abdomen also prevents hip flexion during transfers, leading to poor placement of the trailing hand and subsequently poor glenohumeral alignment.

Appropriate training is suggested if transfer devices are recommended. If a transfer board is used, shear and friction injuries of the skin can be avoided if small lifts with lateral movements are taught rather than a sliding movement along the board.

Exercise

17. Incorporate flexibility exercises into an overall fitness program sufficient to maintain normal glenohumeral motion and pectoral muscle mobility.

(Clinical/epidemiologic evidence–3/4; Ergonomic evidence–NA; Grade of recommendation–C; Strength of panel opinion–Strong)

The American College of Sports Medicine has recommended stretching exercises for the able-bodied population to prevent injury, increase performance, and enhance overall health (ACSM, 1998). Similarly, flexibility and stretching have been promoted in several fitness and exercise program resources for wheelchair users (Froehlich et al., 2002; Lanig et al., 1996; Lockette and Keyes, 1994; Miller, 1995; Hicks et al., 2003).

A common posture in wheelchair users includes protracted shoulders with shortened anterior and lengthened posterior muscles (i.e., upper thoracic kyphosis and protracted scapulae) and a head-forward position. Shortened muscles or restricted range of motion may increase the risk of an upper limb injury and pain. Two separate studies have found an association between restricted range of motion and pain, reduced activity, and/or injury (Ballinger et al., 2000; Waring and Maynard, 1991). Incorporating stretching into an exercise program for individuals who use manual wheelchairs has been associated with decreased reported pain intensity (Curtis et al., 1999). The exercise protocols used in this study included both strengthening and stretching, with stretching being focused on the chest and anterior shoulder muscles.

When an individual with SCI begins a stretching program, the panel suggests the following regimen:

▪ Perform stretching exercises of the neck, upper trunk, and limb a minimum of 2 to 3 times per week.

▪ Perform full range-of-motion exercises with particular attention to the following areas: external rotation of the humerus and retraction and upward rotation of the scapula.

▪ Apply gentle, prolonged stretch in each direction of tightness.

▪ Avoid causing impingement by providing a distractive force along the long axis of the humerus.

▪ Avoid internal rotation when completing overhead range of motion.

Consult additional resources as needed, such as Anderson and Bornell, Stretch and Strengthen for Rehabilitation and Development 1987, and Lockette and Keyes, Conditioning with Physical Disabilities 1994.

18. Incorporate resistance training as an integral part of an adult fitness program. The training should be individualized and progressive, should be of sufficient intensity to enhance strength and muscular endurance, and should provide stimulus to exercise all the major muscle groups to pain-free fatigue.

(Clinical/epidemiologic evidence–3/6; Ergonomic evidence–NA; Grade of recommendation–C; Strength of panel opinion–Strong)

Strengthening exercises have been recommended for the able-bodied population to prevent injury, increase performance, and enhance overall health (ACSM, 1998). Similarly, several authors have recommended strengthening as part of the regular fitness routine for wheelchair users. The basis of this recommendation is that individuals with SCI may be prone to muscle imbalance and selective muscle weakness. Muscle imbalance has been related to pain in athletes with both paraplegia (Burnham et al., 1993) and tetraplegia (Miyahara et al., 1998). Two studies have documented that a strengthening and stretching program can decrease pain (Hicks et al., 2003; Curtis et al., 1999). Exercise should also be encouraged for weight maintenance or reduction, conditioning, endurance, and general well-being. As stated previously, weight gain is likely a risk factor for upper limb injury. Exercise combined with diet modification can help with weight loss and prevention of weight gain.

When an individual with SCI begins a strengthening program, the following is recommended:

▪ Perform one set of 8 to 10 exercises with 8 to 12 repetitions of the major muscle groups, 2 to 3 days per week. Goals for daily repetitions should systematically increase, starting low and gradually working up to target levels.

▪ Pay particular attention to shoulder depressors (i.e., infraspinatus, subscapularis, pectoralis major, and latissimus dorsi) and to scapular stabilizers (e.g., trapezius and rhomboids).

▪ To limit impingement, avoid internal rotation when exercising above the level of the shoulder.