Abstract

Taurine, an important mediator of cellular volume regulation in the central nervous system, is accumulated into neurons and glia by means of a highly specific sodium-dependent membrane transporter. During hyperosmotic cell shrinkage, net cellular taurine content increases as taurine transporter activity is enhanced via elevated gene expression of the transporter protein. In hypoosmotic conditions, taurine is rapidly lost from cells by means of taurine-conducting membrane channels. We reasoned that changes in taurine transporter activity also might accompany cell swelling to minimize re-accumulation of taurine from the extracellular space. Thus, we determined the kinetic and pharmacological characteristics of neuronal taurine transport and the response to osmotic swelling. Accumulation of radioactive taurine is strongly temperature-dependent and occurs via saturable and non-saturable pathways. At concentrations of taurine expected in extracellular fluid in vivo, 98% of taurine accumulation would occur via the saturable pathway. This pathway obeys Michaelis-Menten kinetics with a Km of 30.0 ± 8.8 μM (mean ± SE) and Jmax of 2.1 ± 0.2 nmol/mg protein min. The saturable pathway is dependent on extracellular sodium with an effective binding constant of 80.0 ± 3.1 mM and a Hill coefficient of 2.1 ± 0.1. This pathway is inhibited by structural analogues of taurine and by the anion channel inhibitors, 4,4′-diisothiocyanostilbene-2, 2′-disulfonic acid (DIDS) and 5-nitro-2-(3 phenylpropylamino) benzoic acid (NPPB). NPPB, but not DIDS, also reduces the ATP content of the cell cultures. Osmotic swelling at constant extracellular sodium concentration reduces the Jmax of the saturable transport pathway by approximately 48%, increases Kdiff for the non-saturable pathway by 77%, but has no effect on cellular ATP content. These changes in taurine transport occurring in swollen neurons in vivo would contribute to net reduction of taurine content and resulting volume regulation.

Keywords: Amino acid transport, Cell cultures, Anion channel antagonist

Introduction

Taurine (2-aminoethanesulfonic acid) is one of the most abundant free amino acids in several organs of the body and plays an important role in a variety of essential biological processes (Awapara et al. 1950; Wright et al. 1986). Taurine is involved in neurodevelopment and membrane stabilization and may be a neuromodulator (Huxtable 1992); however, the best understood function of taurine in the central nervous system is as an osmolyte (Pasantes Morales and Schousboe 1988; Pasantes-Morales et al. 2002). Taurine's small size, relative metabolic inertness, and low rate of diffusion across membranes enable cells to maintain high intracellular concentrations of this amino acid. While some cell types, including brain cells, can synthesize taurine from cysteine (Chan-Palay et al. 1982; Beetsch and Olson 1998), the majority of body taurine in most carnivores and humans is derived from the diet (Wright et al. 1986) and is accumulated into cells by a specific membrane transporter.

Accumulation of millimolar concentrations of intracellular taurine is mediated by a high affinity taurine transporter (TauT). Functional loss of this protein leads to defects in vision and exercise performance (Heller-Stilb et al. 2002; Warskulat et al. 2004). The primary amino acid structure for the transporter has been defined in many cell types including mouse and rat brain (Liu et al. 1992; Smith et al. 1992) and is consistent with a monomeric peptide with 12 membrane spanning regions. Specific antibodies raised to unique amino acid sequences from these proteins label a 72 kD protein band on Western Blots (Smith et al. 1992; Han et al. 1999). Two distinct high affinity carrier transporters for taurine have been described in the rodent brain based on amino acid sequence and taurine binding affinities (Pow et al. 2002). While these two transporters show different regional and cellular distribution in the brain, the functional significance of this distribution is not clear. Kinetic analysis of cellular taurine accumulation generally reveals a non-saturable, diffusional component in addition to a high affinity carrier-mediated component (Schousboe et al. 1976; Holopainen et al. 1987; Takahashi et al. 2003). The diffusional component of taurine accumulation movement may represent passive amino acid movement through membrane channels, such as the volume sensitive organic osmolyte and anion channel (Jackson and Strange 1993) and others (Roy and Banderali 1994).

In the brain, taurine is the most important osmotically active organic molecule involved in volume regulation during both hypoosmotic hyponatremia (Verbalis and Gullans 1991) and hyperosmotic dehydration (Trachtman et al. 1988; Bedford and Leader 1993). Through the loss of intracellular taurine and osmotically obliged water, cells avoid potential pathological sequelae which result from persistent alterations in cellular volume (Haussinger et al. 1994; Kimelberg 1995). Brain taurine content is reduced during several days of systemic hypoosmotic conditions and contributes to a significant fraction of the brain volume regulation observed in this condition. With shorter periods of hypoosmolality, brain volume regulation is mediated by loss of inorganic osmolytes with little change in the content of taurine or other organic molecules (Melton et al. 1987). However there is evidence that taurine is redistributed amongst brain cells during the early stage of hypoosmotic hyponatremia. Mobilization of intracellular taurine is indicated by a 5-10 fold increase in the extracellular taurine concentration measured during acute systemic or local hypoosmotic exposure (Solis et al. 1988; Wade et al. 1988). In addition, histochemistry for taurine-like immunoreactivity reveals taurine contents of cerebellar Purkinje cells are reduced while contents of adjacent astroglia are elevated during the first hour of acute hypoosmotic hyponatremia (Nagelhus et al. 1993). The mobilization of taurine and potentially other osmolytes out of neurons and into astrocytes may underlie the observed greater swelling of glial cells relative to that of neurons during pathological conditions characterized by cytotoxic edema (Plum et al. 1963; Klatzo 1967; Wasterlain and Torack 1968; Betz et al. 1989).

Cellular mechanisms that underlie the mobilization and cellular redistribution of taurine during in vivo hypoosmotic hyponatremia are not well understood. In cell culture, taurine is preferentially lost from osmotically swollen neurons as compared with astroglial cells (Olson and Li 2000). We reasoned that, in addition to elevated taurine efflux, the rate of neuronal taurine influx may be reduced during brain swelling to minimize re-accumulation of taurine from the extracellular space and thus, facilitate net transport of taurine from neurons to glia. To explore this mechanism, we determined kinetic and pharmacological characteristics of taurine transport in cultured neurons incubated in normal and hypoosmotic conditions. We focused this study on neurons from the hippocampus because of high content of taurine and taurine transporter protein in hippocampal pyramidal neurons (Pow et al. 2002) and the importance of taurine for osmotic volume regulation of the hippocampus (Kreisman and Olson 2003). Our data suggest neurons rapidly downregulate the taurine transporter when osmotically swollen. These data have been presented in preliminary form (Olson and Martinho 2003; Olson and Martinho in press).

Materials and methods

Materials

Media, sera, and additives for tissue cultures were purchased from Invitrogen Life Technologies, Inc. (Chicago, Illinois). Primary antibodies for glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) and synapsin-25 (SNAP) were purchased from Sternberger Monoclonals (Baltimore, Maryland). Antibodies for neuron specific enolase (NSE) and taurine transporter (TauT) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Company (St. Louis, Missouri) and Chemicon International (Temecula, California), respectively. Fluorescein-conjugated and Texas redconjugated secondary antibodies were obtained from Jackson ImmunoResearch, Inc. (West Grove, Pennsylvania). Goat anti-rabbit antibody conjugated with Alexa Fluor 568 was purchased from Molecular Probes (Eugene, Oregon). Radioactive taurine was from New England Nuclear (Boston, Massachusetts). Cell lysis solutions, enzymes, and buffers for ATP analysis and bicinchoninic acid kit for protein determination were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Company (St. Louis, MO). All other salts and chemicals for HPLC and glutamine synthetase assays came from Fisher Scientific (Fair Lawn, New Jersey) and were the highest grade available.

Primary cell cultures

Hippocampal neuron cultures were prepared from rat fetuses at the eighteenth gestational day using a modified procedure (Scholz et al. 1988) originally described by Banker and Cowen (Banker and Cowan 1977). Pregnant dams were anesthetized to a surgical plane with pentobarbital (65-85 mg/kg) and a sterile laparotomy was performed. All fetuses were removed from the uterus, placed in ice-cold divalent cation-free Hank's balanced salt solution (DCF-HBSS), decapitated, and the hippocampi dissected with the aid of a stereo microscope. Hippocampi pooled from 4-6 fetuses were exposed for 15 min to 0.125% trypsin at 37° C in DCF-HBSS. The tissue then was rinsed three times with DCF-HBSS and triturated by repeated passage through a fire-polished glass pipette. The resulting suspension was centrifuged and the cells resuspended in Eagles' Minimum Essential Medium (E-MEM) medium containing 10% horse serum plus 50 μg/ml streptomycin and 50 U/ml penicillin (Bartlett and Banker 1984) for plating at a density of 30,000 cells/cm2 onto 35 mm plastic Petri dishes or 12 mm glass coverslips previously coated with 5.0 μg/ml polyornithine. After 2 to 4 hours, when the cells have attached to the surface, the medium was changed to neuron growth medium consisting of defined Neurobasal™ medium containing B27 additives, 50 μg/ml streptomycin, 50 U/ml penicillin, and a sufficient volume of 3 M NaCl to raise the osmolality to 290 mOsm (Brewer et al. 1993). Twice each week, one-half of the culture medium was removed and replaced with fresh medium. The percentage of neurons and the presence of contaminating glia were determined by immunocytochemical staining for neuron-specific enolase and GFAP, respectively, and by measuring the activity of glutamine synthetase as described below. Cultures were used after 10-14 days in vitro.

Hippocampal astrocyte cultures are prepared as described by Pappas et al. (1994) using methods similar to those we have described for cerebral cortical astrocyte cultures (Olson and Holtzman 1980). Two to four day-old rat pups were decapitated and the hippocampi dissected with sterile techniques. Tissue from 6-8 animals was softened with 0.125% trypsin for 15 min, vortexed vigorously and then triturated by passage 20-30 times through a 10 ml serum pipette. The cell suspension was filtered through an 80 μm nylon mesh, centrifuged, and the cells resuspended in growth medium consisting of 20% newborn calf serum and 80% E-MEM containing two times the normal amino acid concentrations (except for the glutamine concentration which remains normal) and four times the normal vitamin concentrations. Streptomycin and penicillin also were added (50 μg/ml and 50 U/ml, respectively) as was 19 mM additional sodium bicarbonate (Olson and Holtzman 1981). After 1-2 days in culture, cells were fed with a medium containing only 10% newborn calf serum but otherwise identical to that used for the initial plating. This medium was used for subsequent feedings twice each week. Experiments were performed on cells after 14-21 days in vitro. For some cells, medium was replaced three days prior to experimentation with a 1:1 mixture of conditioned neuron medium removed from hippocampal neuron cultures and fresh neuron growth medium.

Immunocytochemistry

Coverslips containing cells were removed from petri dishes and rinsed twice with staining buffer consisting of 137 mM NaCl and 10 mM Na2HPO4 at pH=7.2. Cells then were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde in this buffer for 15 min. When staining for GFAP, cells also were fixed for 15 min in 95% ethanol containing 10 mM HCl. All fixatives were rinsed from the cover slips using staining buffer containing 0.1% Triton X-100 (SBT). Non-specific antigen sites were blocked with a 30 min exposure to 20% pre-immune goat serum in SBT. Coverslips were rinsed twice and then incubated with SBT for 5 min following this and other antibody exposures described below. Primary mouse antibodies for either GFAP (1:5000) or SNAP (1:5000) plus rabbit antibodies for either NSE (1:100) or TauT (1:100) were applied together for 60 min in SBT. Then, cells were sequentially exposed to goat anti-mouse secondary antibodies conjugated with fluorescein (1:100) and goat anti-rabbit secondary antibodies conjugated with either Texas red (for TauT, 1:300) or Alexa Fluor 568 (for NSE, 1:200) for 30 min each. Some cultures stained for GFAP and NSE also were exposed to 1.0 μg/ml 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) in SBT for 5 min. After a final 10 min incubation and rinse in staining buffer, cells were immersed in distilled water for 10 min. Coverslips were affixed onto glass slides with an aqueous mounting medium (BioMeda Corp, Foster City, CA) and illuminated with epifluorescence for photography. For some coverslips, exposure to one or both of the primary antibodies was omitted.

Glutamine Synthetase

Glutamine synthetase activity was determined in neuronal and glial cell cultures using the method described by Allen et al. (2001). Briefly, cells grown on 35 mm dishes were lysed in a hypotonic imidazole-Triton X-100 buffer and scraped from the dish. The suspension was sonicated and a portion saved for protein determination by the method of Lowry et al. (1951). The remaining suspension was added to a reaction buffer to give final concentrations of 120 mM l-glutamine, 10 mM Na2HAsO4, 50 mM imidazole, 30 mM hydroxylamine, 0.4 mM ATP, and 0.06 mM MgCl2 in 0.8 ml. Blank reactions and standards were performed using fresh imidazole lysis buffer and imidazole lysis buffer with known concentrations of hydroxylglutamate, respectively. After 60 min at 37° C the reaction was stopped with addition of 0.2 ml of 15% FeCl3 in 25% trichloroacetic acid plus 2.5 M HCl and incubated in an ice bath for 30 min. Then the solution was centrifuged and the optical density of the supernatant was determined at 490 nm. Values for cell lysates were compared to those obtained from hydroxylglutamate standards prepared contemporaneously.

Taurine accumulation

Culture medium was removed and cells were washed three times and then incubated at 37° C in isoosmotic phosphate buffered saline (PBS) containing 137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 1.0 mM CaCl2, 0.5 mM MgCl2, 2.7 mM Na2HPO4, 0.5 mM KH2PO4, and 5.5 mM glucose (pH 7.3). Small volumes of 3 M NaCl were added to adjust the osmolality to 290 mOsm. This typically increased the NaCl concentration by approximately 7 mM. After 30 min, PBS in the culture dish was replaced with 1.5 ml of the same PBS plus 0.5-0.75 μCi/ml [3H]-taurine together with various concentrations of unlabeled taurine. For some experiments, the PBS solutions also contained taurine transport inhibitors or other substances. For other experiments, the PBS solution used during [3H]-taurine exposure was made hypoosmotic by reducing the concentration of NaCl to 100 mM and adjusting osmolality to 200 mOsm by adding sucrose. Results from these studies were compared to data from cells incubated in isoosmotic PBS containing 100 mM NaCl plus additional sucrose to adjust the osmolality to 290 mOsm. Unless otherwise noted, taurine accumulation proceeded at 37° C for 0, 10, 20 or 30 min. At the appropriate time point, triplicate 10 μl samples of PBS were removed for radioactivity counting. Then, the cells were rinsed with ice-cold 10 mM tris buffer plus sufficient sucrose to match the osmolality of the PBS used during 3H-taurine exposure. Cells on the culture surface were scraped into 1.0 ml of 0.6 M HClO4 plus 4 mM CsCl and then centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 1 min. A 100 μl aliquot of the resulting supernatant was used for HPLC analysis of amino acids and 800 μl was counted for radioactivity. Precipitated protein remaining on the dish was dissolved with 1.0 ml of 1 M NaOH. This was added to the pellet formed during centrifugation and the protein content determined in the resulting solution by the method of Lowry et al. (1951).

Some taurine accumulation studies were performed at 0° C to determine the temperature dependence of taurine transport. For these studies, cells were chilled on a bed of ice for 30 min prior to exposure to 0° C PBS containing [3H]-taurine. Cells remained on the ice in a closed styrofoam container for the duration of the exposure period. Fixation with 0.6 M HClO4 and subsequent sampling for radioactivity uptake then proceeded at room temperature as described above.

Data for radioactive taurine accumulation were fitted to the sum of carrier-mediated (saturable) transport plus diffusional (non-saturable) transport terms using a nonlinear least squares approximation according to the equation:

| (1) |

where J represents the measured velocity of uptake (nmol/mg protein min), Jmax is the calculated maximal velocity (nmol/mg protein min), Km is the calculated taurine binding constant (μM) for the carrier-mediated component of taurine uptake, Kdiff is the calculated rate constant for the diffusion-mediated uptake mechanism (ml/mg protein min), and [S] is the total extracellular concentration of taurine present during accumulation (μM).

To determine the sodium dependence of taurine uptake, [3H]-taurine accumulation was performed in PBS containing various concentrations of Na+ ranging from 0 to 155 mM. These studies were carried out at a low extracellular taurine concentration to ensure the majority of accumulation was mediated by the saturable component. A zero-sodium PBS solution was made by replacing all NaCl and Na2HPO4 in the PBS with choline chloride and KH2PO4, respectively, and removing KCl to maintain the potassium concentration at 3.2 mM. The sodium concentration of other solutions was adjusted by partial replacement of NaCl in the PBS with choline chloride. For all these solutions, osmolality was adjusted to 290 mOsm by adding choline chloride. Using a nonlinear least squares algorithm, data were fit to the equation:

| (2) |

where J represents the measured velocity of taurine uptake (nmol/mg protein min), is the calculated maximal velocity of taurine uptake at the concentration of taurine present during accumulation (nmol/mg protein min), KNa is the calculated concentration of sodium that produces half-maximal rate of transport (mM), [S] is the concentration extracellular of sodium present during accumulation (mM), and N is the calculated Hill coefficient.

Taurine content

The content of taurine in neuronal cultures was determined as previously described (Olson 1999). Cells on 35 mm petri dishes were rinsed two times in PBS to remove growth medium if present. Cultures then were fixed in 1 ml of 0.6 M HClO4. The cells were loosened from the dish with a rubber policeman and scraped into a microcentrifuge tube together with the acid solution. These tubes were centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 1 min and amino acid contents were determined in the supernatant by HPLC after neutralization with a small volume of 4.5 M KOH and derivitization with o-phthalaldehyde. NaOH (1 M) was added to each petri dish to remove residual precipitated protein and then was transferred to the microcentrifuge tube to dissolve the remaining protein pellet. Protein content was determined in this solution by the method of Lowry et al. (1951).

Medium concentrations of amino acids also were determined by HPLC. A volume of medium was mixed 1:1 with 0.6 M HClO4 and then precipitated material was removed by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 1 min. Amino acid concentrations were determined in the supernatant after neutralization with KOH as described above.

ATP Content

ATP contents of neuron cultures were determined using the luciferin-luciferase method. Cells from a 35 mm culture dish were rinsed free of culture medium, if present, and then lysed with 200 μl mammalian cell lysis solution. A 10 μl aliquot was added to luciferin-luciferase enzyme solution and the initial light emission determined with a luminometer. Data were compared with ATP standards to calculate the total ATP content of each dish. This result was normalized to the protein content of the cell lysate determined using the bicinchoninic acid method.

Statistical analyses

Unless otherwise indicated, quantitative data are expressed as the mean ± SEM of results obtained from independent replicate experiments. Parameters from regression analyses are given as the calculated value ± SE of the approximation. Differences in mean values between control and experimental groups were analyzed using Student's t-test or ANOVA followed by Dunnett's test as appropriate. Significant differences in parameters calculated from curve fits of different data sets were determined using ANOVA, ANCOVA and linear or nonlinear regression analyses. Values were assumed significantly different for p < 0.05.

Results

The taurine transporter is strongly expressed in hippocampal neurons

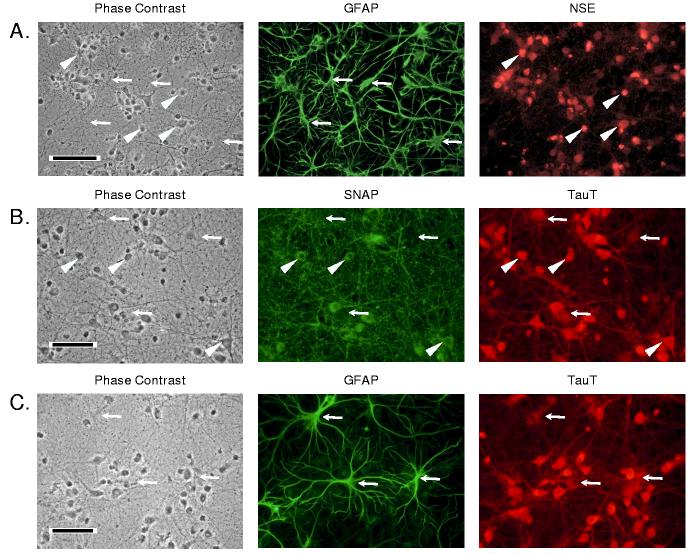

Immunocytochemical analysis of the hippocampal neuron cultures revealed a mixed population of cells predominantly comprised of neurons (Figure 1A). NSE-positive neurons had rounded phase-dark cell bodies while GFAP-positive astrocytes appeared flattened and were less dark under phase contrast microscopy. GFAP-positive cells had multiple branching processes extending for several hundred microns. Numerous SNAP-positive neuron cell bodies were present throughout the culture within a dense matrix of finely branching SNAP-positive fibers and thicker cell processes. Immunostaining of hippocampal glial cultures revealed approximately 95% of the cells were positive for GFAP (data not shown) as we and others previously described for cerebral and hippocampal astrocyte cultures (Olson and Holtzman 1980; Pappas and Ransom 1994).

1.

Images of 14 day-old hippocampal neuron cultures simultaneously immunostained for (A) glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) and neuron-specific enolase (NSE), (B) synapsin-25 (SNAP), and taurine transporter (TauT), or (C) GFAP and TauT. Each panel shows the same field illuminated for phase contrast and for each of the secondary immunofluorescent antibodies as indicated. The black bar in each phase contrast panel represents 50 μm. A. Arrowheads and arrows indicate neuron and glial cell bodies, respectively. B. Arrowheads indicate several neuron cell bodies. The arrows point to regions unlabeled with SNAP but showing significant TauT staining. C. Arrows indicate glial cell bodies and processes stained for both GFAP and TauT.

Immunostaining for TauT demonstrated labeling of both neuron (SNAP-positive) and astroglial (GFAP-positive) cell bodies (Figures 1B and 1C). In addition, numerous neuronal and glial processes showed positive TauT immunoreactivity throughout the culture. The intensity of TauT labeling was consistently lower in GFAP-positive and SNAP-negative cells compared with other cells observed in the same microscopic field.

Cell counts in neuron cultures prepared at several times over a six month period yielded 22 ± 2% GFAP-positive cells relative to all cells with DAPI-stained nuclei (mean ± SD, N = 4). Similar results for the astrocyte content of neuron cultures were obtained by comparing glutamine synthetase (GS) activity in astroglial and neuronal cultures. The GS specific activity of astrocyte cultures grown continuously in astrocyte growth medium containing 10% calf serum was 35.7 ± 0.7 nmol/mg protein min. This activity increased by 51% to 54.0 ± 7.8 nmol/mg protein min when these cells were exposed for three days to neuron growth medium prior to measurement of enzyme activity (p < 0.05). In contrast, the specific activity of GS in neuron cultures was 12.8 ± 2.2 nmol/mg protein min, or approximately 24% of the specific activity measured in astrocyte cultures exposed to neuron growth medium.

Neuron cultures accumulate net taurine

Although the freshly prepared neuron culture growth medium does not contain taurine, we measured a concentration of 2.5 ± 0.1 μM, in medium removed from cultures just prior to experimentation. Cellular content of taurine in the cultures was 10.6 ± 0.7 nmol/mg protein and did not change during the initial 30 min incubation in PBS. Cultures subsequently incubated with PBS containing 100 μM taurine showed a linear increase in taurine content over 30 min at a rate of 2.14 ± 0.08 nmol/mg protein min (r2 = 0.96).

Neuronal taurine accumulation is temperature and sodium dependent

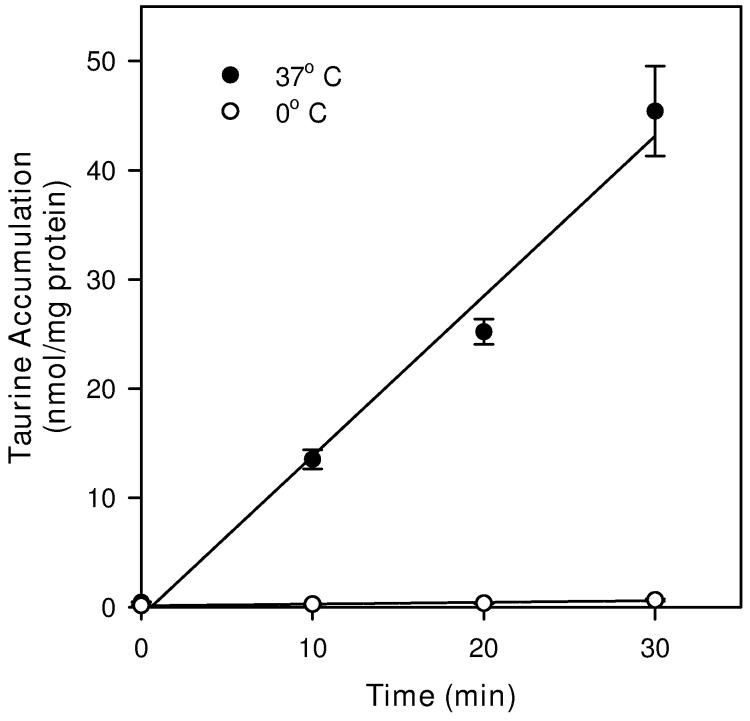

Cultures maintained at 37° C during accumulation of tritium-labeled 100 μM taurine also showed a linear uptake for 30 min (Figure 2). The uptake rate, calculated as the slope of the linear regression fit to the data, was 1.46 ± 0.13 nmol/mg protein min (r2 = 0.98). This rate was reduced by nearly 99% to 0.016 ± 0.003 nmol/mg protein min (r2 = 0.92) for cultures maintained on a bed of ice prior to and during the period of taurine accumulation. The linearity of the graphs of taurine accumulation versus time at both temperatures suggests rates of uptake are constant throughout this interval. Except where noted, all subsequent studies of taurine accumulation were performed with a 20 min period of exposure to the radiolabeled compound.

2.

Time and temperature dependence of taurine accumulation in hippocampal neuron cultures. Cells were exposed to tracer quantities of [3H]-taurine in isoosmotic PBS containing 100 μM unlabeled taurine for the times and at the temperatures indicated before sampling to determine cellular taurine accumulation. Data points are the mean ± SEM of 6-9 independent measurements. Straight lines are drawn for the best fit linear regression to all data points.

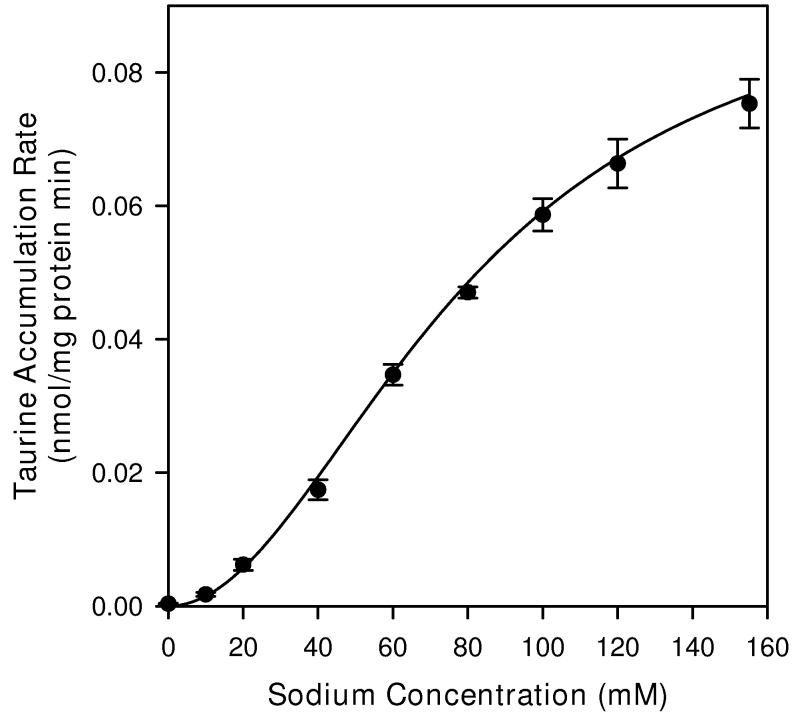

Taurine accumulation in neuron cultures was strongly dependent on the concentration of extracellular sodium (Figure 3). These studies were performed with 1 μM extracellular taurine to minimize the contribution of the non-saturable component of uptake (see below). In PBS made without sodium, the taurine accumulation rate was reduced to approximately 0.5% of the value measured in cells incubated with normal PBS. For values of extracellular sodium concentration between 0 and 155 mM the relationship between extracellular sodium concentration and taurine accumulation was sigmoidal. Non-linear regression analysis yielded a Km for sodium of 80.0 ± 3.1 mM and a Hill coefficient of 2.05 ± 0.09. If the Hill coefficient was fixed at 2.0 in the regression analysis, the calculated Km for sodium became 81.4 ± 1.6 mM.

3.

Sodium dependence of taurine accumulation in hippocampal neuron cultures. Cells were exposed to tracer quantities of [3H]-taurine plus 1 μM unlabeled taurine in isoosmotic PBS containing the indicated sodium concentration for 20 min before sampling to determine cellular taurine accumulation. Sodium chloride was replaced with choline chloride in solutions with reduced sodium concentrations. Data points are the mean ± SEM of 4-5 independent measurements. The smooth line is drawn according to the best fit non-linear regression to a second order Michaelis-Menten equation as described in the text.

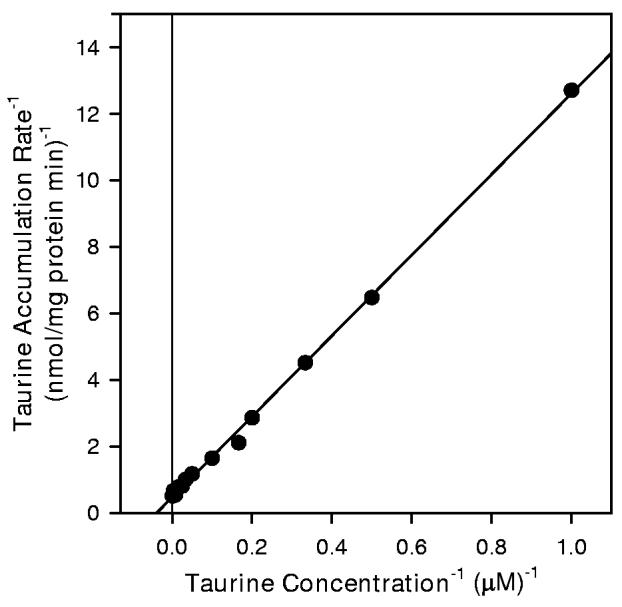

Taurine accumulation kinetics is comprised of saturable and non-saturable components

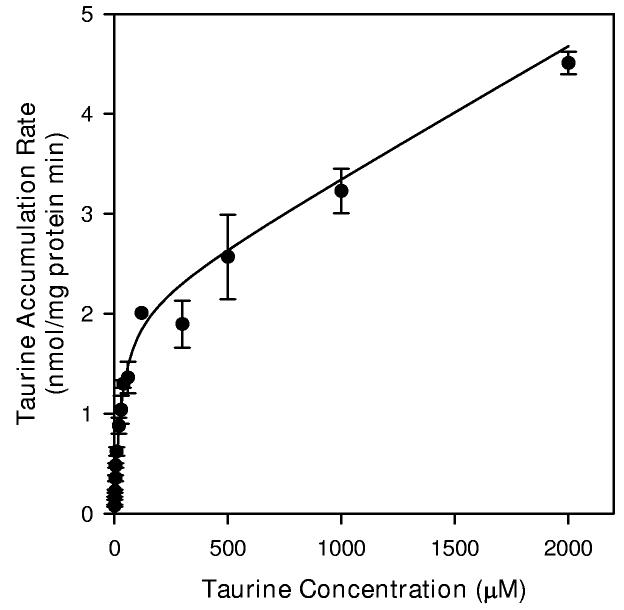

The dependence of taurine accumulation on extracellular taurine concentration appeared to consist of Michaelis-Menten (saturable) and linear (non-saturable) kinetic components (Figure 4). Non-linear regression analysis of the data to fit Equation 1 yielded Km and Jmax values for the saturable component of 30.0 ± 8.8 μM and 2.10 ± 0.23 nmol/mg protein min, respectively. The calculated coefficient for the non-saturable component (Kdiff) was 0.0013 ± 0.0002 ml/mg protein min. Subtracting the non-saturable component from data gathered at each taurine concentration and replotting the results as a double reciprocal graph yielded a strongly linear relationship (Figure 4B).

4.

Taurine transport kinetics of hippocampal neuron cultures. (A) Cells were exposed to the indicated concentration of unlabeled taurine plus tracer quantities of [3H]-taurine in isoosmotic PBS for 20 min before sampling to determine cellular taurine accumulation. Data points are the mean ± SEM of 2-6 independent measurements. The smooth line is drawn according to the best fit non-linear regression to the sum of saturable plus nonsaturable components of taurine accumulation as described in the text. (B) Double reciprocal plot of the mean values at each taurine concentration following subtraction of the calculated non-saturable component. The line represents the best fit linear regression analysis (r2 = 0.999).

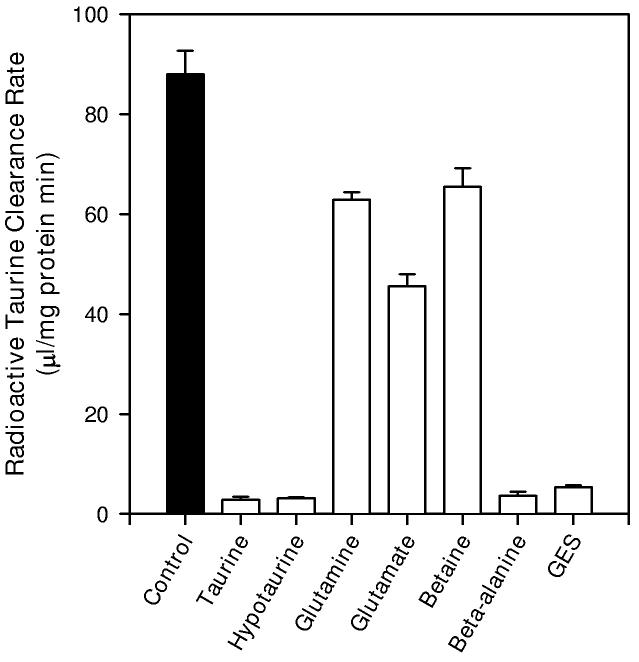

The saturable component of taurine transport is specific for taurine

Accumulation of tracer quantities of [3H]-taurine was strongly inhibited by unlabeled taurine and by structural analogs of taurine (Figure 5). At 1 mM concentrations, taurine, hypotaurine, β-alanine and guanidinoethanesulfonate (GES) inhibited radiolabeled taurine accumulation to less than 5% of the control value. In contrast, 1 mM glutamine, glutamate, or betaine, substrates for various other membrane transporters (Palacin et al. 1998), had significantly smaller effects on taurine accumulation; reducing the accumulation rate to values ranging from 50% to 70% of the control value.

5.

Inhibitors of taurine accumulation in hippocampal neuron cultures. Cells were exposed to tracer quantities of [3H]-taurine in isoosmotic PBS containing 1 μM unlabeled taurine (control) or to the same specific activity of taurine plus 1 mM of the indicated compound for 20 min before sampling to determine radioactive taurine accumulation. Results are expressed as the radioactivity cleared from a volume of extracellular fluid in order to compare inhibition by added unlabeled taurine with that of other compounds. Data points are the mean ± SEM of 5-6 independent measurements. All values from cultures with added compounds are significantly different from the control accumulation rate.

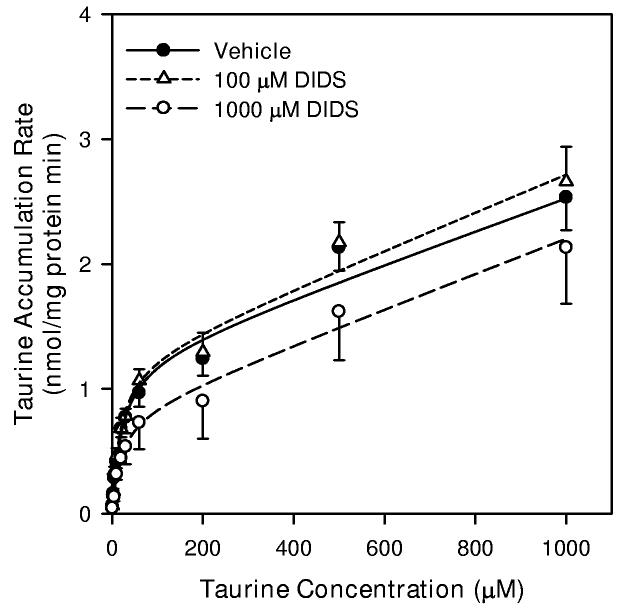

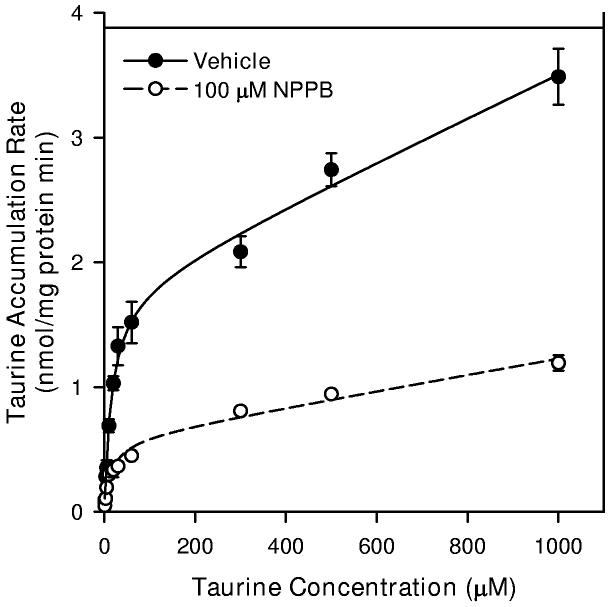

DIDS and NPPB inhibit saturable and non-saturable components of neuronal taurine transport

In an attempt to isolate the saturable component of neuronal taurine accumulation, we measured uptake at various concentrations of taurine in the presence of the anion channel and organic osmolyte efflux inhibitors, 5-nitro-2-(3 phenylpropylamino) benzoic acid (NPPB) or 4,4′-diisothiocyanostilbene-2, 2′-disulfonic acid (DIDS) (d'Anglemont de Tassigny et al. 2003). For these studies, cells were exposed to drug or drug vehicle (0.3% DMSO) for 10 min prior to the addition of radioactive taurine as well as throughout the period of taurine accumulation. The resulting kinetic data were fit to the form of Equation 1. Vehicle alone and 100 μM DIDS had no effect on Jmax, Km, or Kdiff in isoosmotic conditions (Figure 6A). However, 1000 μM DIDS inhibited Jmax by 35% but had no effect on Km and Kdiff. Similarly, in isoosmotic PBS, 100 μM NPPB reduced Jmax of the saturable component by 67% and Kdiff of the non-saturable component by 63%. This concentration of NPPB had no effect on Km for the saturable component (Figure 6B).

6.

Taurine transport kinetics of hippocampal neuron cultures in the absence and presence of anion channel blockers. Cells were exposed to the indicated concentration of taurine plus tracer quantities of [3H]-taurine in isoosmotic PBS for 20 min before sampling to determine cellular taurine accumulation. For some cultures, drugs were added 10 min prior to and throughout the 20 min exposure to [3H]-taurine. The drug vehicle was 0.3% DMSO. Smooth lines are drawn according to the best fit non-linear regression to the sum of saturable plus non-saturable components of taurine accumulation as described in the text. Data points are the mean ± SEM of 4-5 independent measurements. (A) Taurine accumulation during exposure to 100 μM DIDS, 1000 μM DIDS, or drug vehicle. (B) Taurine accumulation during exposure 100 μM NPPB or drug vehicle.

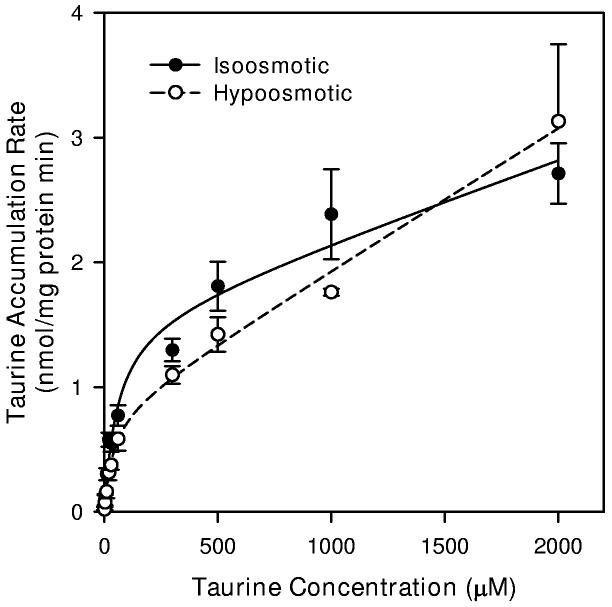

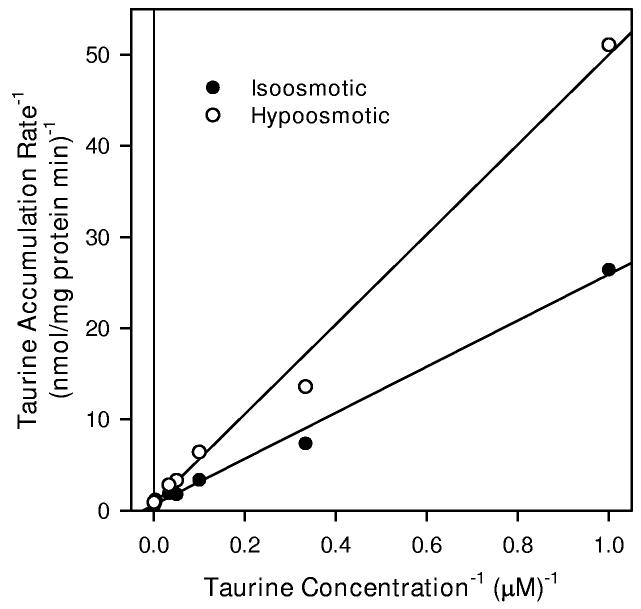

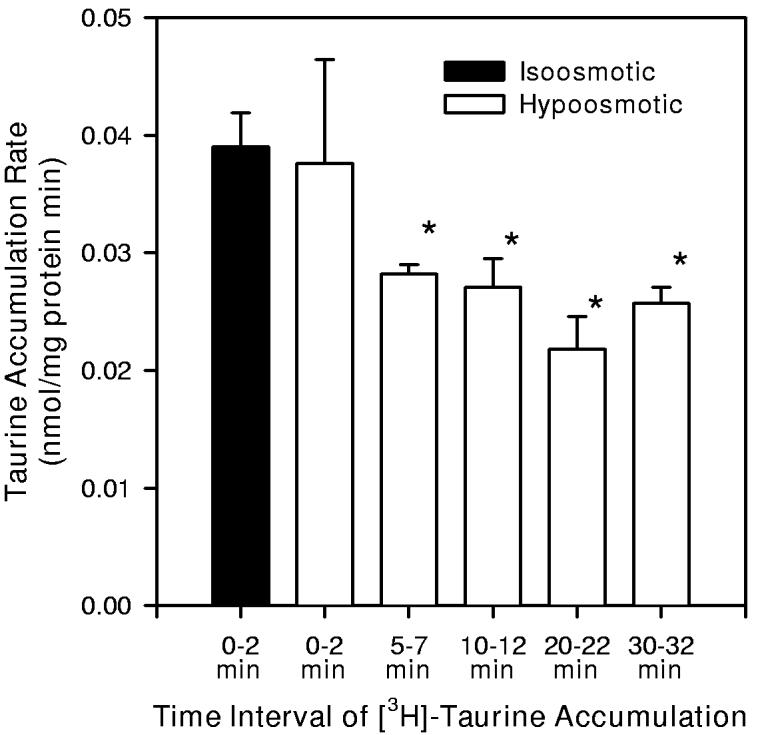

Taurine transport is downregulated by osmotic swelling

The rate of taurine accumulation in hippocampal neuron cultures was reduced by hypoosmotic exposure (Figure 7). In initial studies, taurine accumulation was determined with tracer quantities of [3H]-taurine plus 1 μM unlabeled taurine to minimize the contribution of the non-saturable component of accumulation to the calculated rate of taurine uptake. Based on results shown in Figure 4, 98% of the accumulated taurine occurs via the saturable component at this concentration of extracellular taurine. Because of the strong dependence of the transporter on extracellular sodium (Figure 3), both isoosmotic and hypoosmotic PBS solutions used for these studies were formulated to have the same concentration of NaCl (100 mM). Radioactive taurine was added after various periods of hypoosmotic exposure and cells were prepared for sampling 2 min later. Taurine accumulation measured in the 2 min beginning immediately after the introduction of hypoosmotic PBS was not different from that measured in cultures exposed only to isoosmotic conditions. After 5 min in hypoosmotic PBS, the rate of taurine accumulation was reduced by approximately 28% and remained at this diminished level for least 30 min of hypoosmotic exposure.

7.

Inhibition of taurine accumulation in hippocampal neuron cultures by hypoosmotic exposure. Cells were exposed to isoosmotic or hypoosmotic PBS containing 1 μM taurine. A tracer quantity of [3H]-taurine was added to the PBS during the indicated time intervals. Then cells were rapidly sampled to determine cellular taurine accumulation. The sodium concentration of both isoosmotic and hypoosmotic PBS was 100 mM. Data are the mean ± SEM of 5 independent measurements. * indicates mean values which are significantly different from the measurement made in isoosmotic PBS at time t = 0 min.

The reduction in taurine transport by the saturable transporter indicated in Figure 7 may result from a shift in Km to a higher value or a reduction in Jmax. To explore these possibilities, we evaluated the entire kinetic curve for taurine accumulation using extracellular taurine concentrations ranging from 1 μM to 2000 μM (Figure 8). Analysis of these data by ANCOVA showed a significant effect of osmolality on the resulting rate of accumulation. Data fit to the form of Equation 1 resulted in a calculated Jmax value which was approximately 48% lower in hypoosmotic PBS than that obtained in isoosmotic PBS (Table 1). In contrast, the values for Km were similar for cells in each osmolality. Kdiff for the non-saturable component was 77% higher for cells in hypoosmotic conditions. Subtracting the calculated non-saturable component from each mean value of the kinetic curve and plotting the resulting data as double reciprocal plots gave linear relationships which show a similar intercept on the abscissa but different slopes (Figure 8B).

8.

Taurine transport kinetics of hippocampal neuron cultures in isoosmotic and hypoosmotic conditions. (A) Cells were exposed to the indicated concentration of taurine plus tracer quantities of [3H]-taurine in isoosmotic or hypoosmotic PBS for 20 min before sampling to determine cellular taurine accumulation. Smooth lines are drawn according to the best fit non-linear regression to the sum of saturable plus non-saturable components of taurine accumulation using parameters given in Table 1 as described in the text. Data points are the mean ± SEM of 3-4 independent measurements. Error bars are not shown if they are smaller than the graph symbol. (B) Double reciprocal plots of the mean values at each taurine concentration following subtraction of the calculated non-saturable component. Straight lines represent the best fit linear regression analyses of the resulting data points (Isoosmotic r2 = 0.994, Hypoosmotic r2 = 0.993).

Table 1.

Calculated kinetic parameters for taurine accumulation into cultured hippocampal neurons incubated in isoosmotic and hypoosmotic conditions.

| Jmax nmol/(mg protein min) |

Km μM |

Kdiff ml/(mg protein min) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Isoosmotic | 1.58 ± 0.23 | 57 ± 22 | 0.00064 ± 0.00015 |

| Hypoosmotic | 0.82 ± 0.22* | 38 ± 29 | 0.00113 ± 0.00016* |

Values are the mean ± SE of the parameters calculated using a non-linear least squares method as described in the text.

indicates parameters which are significantly different from the value measured in isoosmotic conditions.

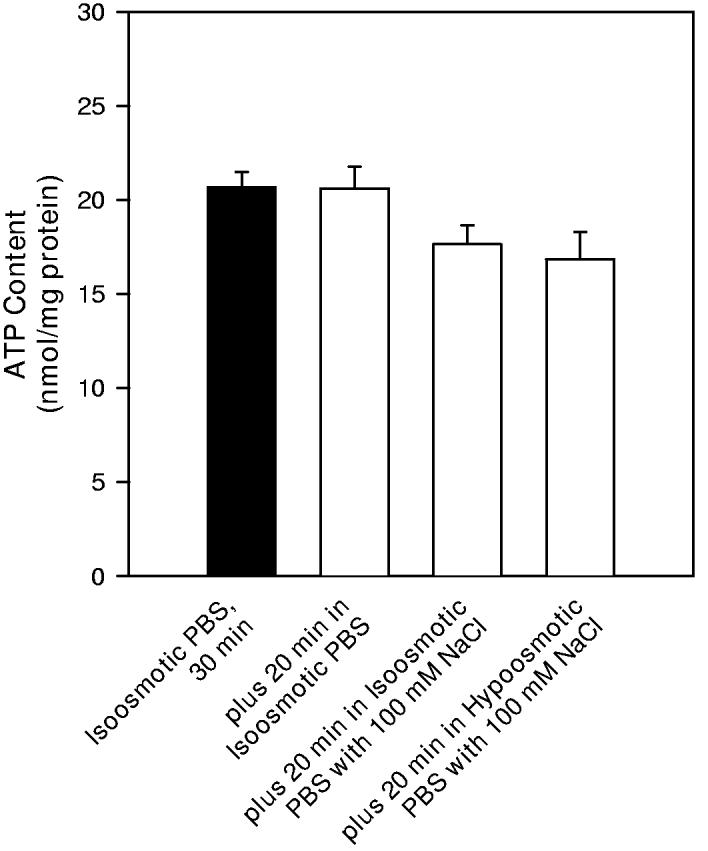

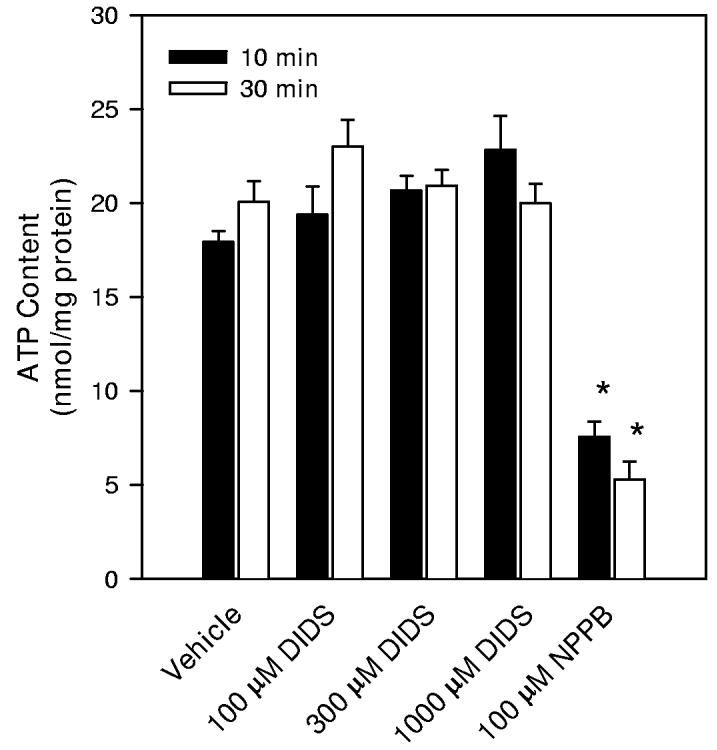

Neuronal ATP is not altered by hypoosmotic exposure

ATP content of neuron cultures was measured in conditions similar to those used for taurine accumulation studies. After incubation for 30 min in isoosmotic PBS, neuron culture ATP content was 20.7 ± 0.8 nmol/mg protein (Figure 9A). This content was not changed for cells incubated for an additional 20 min in isoosmotic PBS, a time period equal to that used during taurine accumulation studies. Following the initial 30 min PBS incubation, ATP content was insignificantly reduced for cultures incubated for 20 min in hypoosmotic PBS containing only 100 mM NaCl. This value was not different for cells incubated for an equivalent period of time in isoosmotic PBS containing the same reduced NaCl concentration.

9.

ATP contents of hippocampal neuron cultures. Drug and osmolality treatments were performed similarly to those used when measuring taurine accumulation. (A) ATP contents were first determined after a 30 min incubation period in isoosmotic PBS (solid bar). Then the PBS bathing the culture was changed to either fresh isoosmotic PBS, isoosmotic PBS with reduced NaCl concentration, or hypoosmotic PBS as indicated. After 20 min in these PBS solutions, cells were sampled for ATP contents (open bars). (B) Drugs or drug vehicle was added during the last 10 min of the initial 30 min incubation period in isoosmotic PBS. ATP contents were measured at the end of this 10 min drug exposure period (solid bars) or after an additional 20 min of drug treatment (open bars). * indicates mean values which are significantly different from the measurement made in isoosmotic PBS at the same time point.

When measuring taurine accumulation in the presence of DIDS and NPPB, the drugs were added to the incubation PBS 10 min prior to the start of the 20 min period of taurine accumulation. Therefore, we measured neuron culture ATP contents after 10 min of drug or vehicle exposure and, in other cultures, after an additional 20 min of drug or vehicle exposure. DIDS was found to have no effect on ATP content at concentrations as high as 1000 μM (Figure 9B). In contrast, 100 μM NPPB caused a 63% and 74% decrease in ATP content after the initial 10 min exposure and after the additional 20 min exposure period, respectively.

Discussion

These data describe kinetic and pharmacological characteristics of taurine transport in cells cultured from fetal rat hippocampus and the response of taurine transport mechanisms to osmotic swelling. The majority of cells in these cultures are neurons which strongly express the taurine transporter in their cell bodies and processes. We found astrocytes comprise 22-24% of the cultured cells as determined by cell counts of GFAP-positive cells and by in vitro determination of glutamine synthetase activity. Astroglial cells, characterized by positive GFAP immunostaining, also demonstrated immunoreactivity for TauT; however, the intensity of staining was significantly lower than that observed for neurons in the same microscopic field of view. Thus, we expect our data regarding the saturable component of taurine accumulation primarily reflect characteristics of TauT in cultured neurons.

Taurine is not a component of the defined growth medium used for these cell cultures (Brewer et al. 1993). Nevertheless, about 2.5 μM taurine was detected in the growth medium at the time of experimentation. This concentration is similar to that typically measured in CSF or in vivo microdialysis of extracellular fluid (Wade et al. 1988; Lehmann 1989; Solis et al. 1990; Stover and Unterberg 2000) and is not likely to be high enough to cause downregulation of TauT gene expression as has been observed in other cell types (Jones et al. 1990; Bitoun and Tappaz 2000; Kang et al. 2002). Using this value for the taurine concentration in the interstitial fluid and the kinetic data shown in Figure 4A, we calculate that approximately 98% of neuronal taurine accumulation would be facilitated by the saturable transport mechanism in vivo.

We found that uptake of radiolabeled taurine in the hippocampal neuronal cultures is linear over time for at least 30 min indicating that appreciable quantities of accumulated radioactive taurine are not lost from the cells during this period. Thus, our data represent unidirectional taurine accumulation. The kinetics of taurine accumulation is similar to that described in other preparations of nervous system tissue including glial cells, synaptosomes, and cerebral endothelial cells (Schousboe et al. 1976; Kontro and Oja 1978; Holopainen et al. 1987; Sanchez-Olea et al. 1991; Beetsch and Olson 1993; Tamai et al. 1995; Qian et al. 2000). The relationship between the rate of taurine accumulation and the extracellular taurine concentration between 1 μM and 2000 μM in these diverse cell systems appears to represent the sum of saturable and non-saturable components. Similar to rat synaptosomes and astrocytes, taurine accumulation in rat hippocampal neurons is strongly temperature dependent (Hruska et al. 1978; Kontro and Oja 1978; Beetsch and Olson 1993). This property has been associated with energy dependent transporters and is consistent with the absolute dependence on a sodium gradient for taurine accumulation (Smith et al. 1992; Qian et al. 2000). The saturable component of taurine accumulation in neuron cultures shows a strong dependence on extracellular sodium with a Hill coefficient of 2 and significant inhibition by GES and other structural analogs of taurine. Inhibition of taurine accumulation by the amino acids glutamate and glutamine and by the quarternary amine, betaine, is markedly lower. Some portion of the inhibition by glutamate may result from a reduction in the sodium gradient caused by activation of ionotropic glutamate receptors known to be present on these cells (Dingledine et al. 1999; Xin et al. 2005). The Jmax we report here for saturable taurine transport in rat hippocampal neuron cultures is higher than values we previously reported from primary rat cerebral astroglial cultures (Beetsch and Olson 1993) and others have reported for rat astrocytes (Larsson et al. 1986; Sanchez-Olea et al. 1991) and bovine endothelial cells (Qian et al. 2000). This result is consistent with the high taurine content observed in hippocampal pyramidal neurons in vivo (Pow et al. 2002).

In response to hypoosmotic swelling, the Jmax of the saturable component of neuronal taurine accumulation is significantly diminished. This reduction in maximal transport rate occurs independent of changes in extracellular sodium and chloride concentrations and requires several minutes to develop. Thus, it does not appear to be a direct result of abrupt cellular swelling or a decrease in the magnitude of ion gradients necessary for taurine transporter activity. Indeed, cellular swelling likely to occur rapidly during hypoosmotic exposure would dilute the intracellular sodium concentration. Consequently, the net sodium gradient driving carrier-mediated taurine accumulation in these cells would be expected to be larger in the hypoosmotically treated cells compared to those in isoosmotic PBS with the same extracellular NaCl concentration. In addition, the reduction in taurine transport rate is not due to a diminished energy state of the cell as ATP contents are similar for cells in hypoosmotic and isoosmotic conditions with similar sodium contents. Finally, the saturable transporter Jmax remains downregulated for at least 30 min during persistent hypoosmotic exposure, a period when regulatory volume decrease is likely to occur (Pasantes-Morales et al. 1993; Olson and Li 2000). In contrast to these data on rat hippocampal neurons, Sanchez-Olea et al. (1991) showed no effect of osmotic swelling on cultured rat astroglial taurine transporter activity. This differential response to osmotic swelling occurring in vivo would contribute to net transfer of taurine from neurons to glial cells. Such an osmolyte transfer has been observed in the cerebellum of hypoosmotic hyponatremic rats (Nagelhus et al. 1993).

Mechanisms responsible for reduced taurine transporter activity in osmotically swollen cultured neurons are not clear from these studies; however, preliminary data suggest tyrosine kinase activity is required (Olson and Martinho in press). For kidney cells, retina, and astrocytes, activation of PKC leads to decreased carrier-mediated taurine accumulation (Loo et al. 1996; Tchoumkeu-Nzouessa and Rebel 1996; Han et al. 1999). However, no effect of PKC on neuronal taurine accumulation is observed (Tchoumkeu-Nzouessa and Rebel 1996), suggesting control of TauT in different cell types is mediated by different biochemical pathways. In addition to direct modification of the transporter molecule, the protein may be removed form the plasma membrane and sequestered into intracellular sites as has been described in kidney cells by Chesney et al. (1989).

We utilized drugs known to inhibit passive anion and organic osmolyte movements in an attempt to separate and isolate the saturable and non-saturable components of taurine accumulation. We found DIDS had no effect on the non-saturable component of taurine accumulation in cells maintained in normal isoosmotic conditions. Thus, the pathway responsible for this component of influx has different pharmacological characteristics from that of the swelling-activated taurine efflux pathway described in other cell types (Sanchez-Olea et al. 1991; Warskulat et al. 1997; Deleuze et al. 1998; Grant et al. 2000). However, we also found 1000 μM DIDS significantly reduced the Jmax of the saturable component. The reduced maximal transport rate occurred without any apparent change in the energy status of the cells suggesting this drug may interact directly with the transporter protein.

NPPB produced even greater effects on neuronal taurine transport. In isoosmotic conditions, this drug reduced the Jmax of the saturable component of taurine transport at a concentration that also significantly reduced the non-saturable component of taurine accumulation and rapidly and drastically reduced the ATP content of the neurons. Thus, the reduction in Jmax may be a result of diminished sodium gradient in some or all of the cells in the dish resulting from compromised energy status. NPPB is known to have significant effects on volume-activated taurine release and anion conductance in cultured rat neurons, astroglial cells, and other cell types (Strange et al. 1993; Sanchez-Olea et al. 1996; Ordaz et al. 2004). This drug also inhibits volume regulation of adult rat hippocampal slices exposed to hypoosmotic conditions (Kreisman and Olson 2003). While widely regarded as an inhibitor of anion channels (d'Anglemont de Tassigny et al. 2003), NPPB also has been shown to reduce cellular ATP content in skate hepatocytes (Ballatori et al. 1995) and to interact with band 3 protein (Branchini et al. 1995), Na-K-2Cl cotransporter (Wangemann et al. 1986), adenylcyclase (Heisler 1991), and photosystem II of thyalkoid membranes (Bock et al. 2001). NPPB was found to block the CFTR anion channel by interacting deep within the pore structure (Zhang et al. 2000). Thus, in addition to reducing the cellular energy state, this drug may block the taurine transporter by interfering with the chloride or the taurine binding sites on the molecule. A complete understanding of NPPB's action on neuronal taurine transport must await more detailed pharmacokinetic analysis.

Because of its linearity with the concentration of extracellular taurine, the non-saturable component of taurine accumulation has been ascribed to passive movement of taurine through membrane channels. We recently described taurine currents in cultured hippocampal neurons (Li and Olson 2004) that have characteristics similar to taurine-conducting channels or taurine currents in cultured rat cerebral and hippocampal astroglial cells (Jackson and Strange 1993; Roy and Banderali 1994; Olson and Li 1997). The voltage-current relationship for the neuronal pathway is only slightly outwardly rectifying suggesting anionic taurine may diffuse passively with nearly equal facility in either direction. The apparent activation of the non-saturable component of taurine accumulation by osmotic swelling also is consistent with taurine movements through channels since anion and taurine conductance as well as unidirectional taurine efflux have been shown to increase in a variety of cells during hypoosmotic exposure (Pasantes-Morales et al. 1990; Jackson and Strange 1993; Olson and Li 1997). Additionally, we observed that NPPB, a potent inhibitor of taurine efflux and volume activated anion channels (d'Anglemont de Tassigny et al. 2003), reduces, but does not completely block, the non-saturable component of taurine neuronal accumulation in isoosmotic conditions. In contrast, DIDS does not alter this non-saturable neuronal taurine accumulation pathway. In other systems, 1000 μM and lower concentrations of DIDS inhibit plasma membrane anion movement via calcium-activated and voltage-sensitive channels and cotransporters and volume-sensitive taurine fluxes (Sanchez-Olea et al. 1991; Thinnes and Reymann 1997; Romero and Boron 1999; Hoffmann 2000; Fuller et al. 2001). However, in many cell types, DIDS does not affect taurine efflux in isoosmotic conditions (Warskulat et al. 1997; Deleuze et al. 1998; Grant et al. 2000). These results imply transport mechanisms in addition to NPPB- and DIDS-sensitive plasma membrane channels are responsible for the non-saturable accumulation of taurine into these cultured neurons in isoosmotic PBS.

Under steady state conditions, intracellular taurine concentration is determined by the rate of accumulation via the saturable taurine transporter and the rate of taurine efflux through passive and non-saturable pathways such as anion and organic osmolyte conducting channels. The rate of taurine accumulation depends on the extracellular taurine concentration while the rate of taurine efflux depends on the gradient of taurine across the plasma membrane. Assuming complete reversibility of the non-saturable pathway, we can use this measured component of taurine accumulation to calculate an approximate rate of passive taurine efflux. With this assumption, we compute a steady state intracellular taurine concentration of 0.12 mM at 2.5 μM extracellular taurine, the value we measured in neuron culture growth medium. With a neuronal cell volume of 4.6 μl/mg protein (Olson and Li 2000), this intracellular taurine concentration is equivalent to 0.56 nmol/mg protein. However, this calculated value of neuronal taurine content is substantially smaller than the 10.6 nmol/mg protein measured for cells freshly removed from neuron growth medium. There may be several reasons for this discrepancy. Potentially, the nonsaturable component is not symmetric, allowing a higher permeability for taurine influx compared with taurine efflux. The lack of change in neuronal taurine contents during the initial 30 min incubation in PBS without added taurine provides support for this hypothesis. Alternatively, the saturable and non-saturable components of taurine accumulation measured in neuron cultures may reside in different cellular compartments. For example, the saturable component may be predominately expressed in neurons while the non-saturable component may be equally expressed in neurons and glial cells. The kinetic data also are consistent with a low affinity transporter in parallel (at the cell membrane) or in series (e.g. at an intracellular organelle) with the neuronal plasma membrane taurine transporter protein. Low affinity plasma membrane taurine transporters have been described in Ehrlich ascites tumor, human carcinoma, and retinal cells (Militante and Lombardini 1999; Wersinger et al. 2001; Poulsen et al. 2002). Additionally, significant intracellular localization of TauT at intracellular sites including mitochondria and the nuclear membrane is consistent with a model of taurine accumulation into organelles in series with its accumulation into the cytosol (Voss et al. 2004; Christensen et al. 2005). Finally, de novo synthesis of taurine by these cells may maintain a higher intracellular concentration of taurine than predicted by this analysis of unidirectional fluxes (Chan-Palay et al. 1982). Some of these possibilities may be addressed in the future using neuron cultures of higher purity or with glia-specific metabolic poisons. A more detailed analysis of intracellular localization of taurine and the transporter protein also may further characterize the components of neuronal taurine accumulation.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge technical assistance provided by James Leasure and Guangze Li. This research was supported by NIH grant R01-NS37485 (JEO) and a Coordenadoria de Aperfeicoamento de Pessoal de Nivel Superior fellowship to EM.

References

- Allen JW, Mutkus LA, Aschner M. Mercuric chloride, but not methylmercury, inhibits glutamine synthetase activity in primary cultures of cortical astrocytes. Brain Res. 2001;891:148–157. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)03185-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awapara J, Landua AJ, Fuerst R. Distribution of free amino acids and related substances in organs of the rat. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1950;5:457–462. doi: 10.1016/0006-3002(50)90191-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballatori N, Truong AT, Jackson PS, Strange K, Boyer JL. ATP depletion and inactivation of an ATP-sensitive taurine channel by classic ion channel blockers. Mol Pharmacol. 1995;48:472–476. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banker GA, Cowan WM. Rat hippocampal neurons in dispersed cell culture. Brain Res. 1977;126:397–342. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(77)90594-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett WP, Banker GA. An electron microscopic study of the development of axons and dendrites by hippocampal neurons in culture. II. Synaptic relationships. J Neurol Sci. 1984;4:1954–1965. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.04-08-01954.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedford JJ, Leader JP. Response of tissues of the rat to anisosmolality in vivo. Am J Physiol. 1993;264:R1164–1179. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1993.264.6.R1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beetsch JW, Olson JE. Taurine transport in rat astrocytes adapted to hyperosmotic conditions. Brain Res. 1993;613:10–15. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)90447-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beetsch JW, Olson JE. Taurine synthesis and cysteine metabolism in cultured rat astrocytes: effects of hyperosmotic exposure. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:C866–874. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.274.4.C866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betz AL, Iannotti F, Hoff JT. Brain edema: a classification based on blood-brain barrier integrity. Cerebrovasc Brain Metab Rev. 1989;1:133–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitoun M, Tappaz M. Taurine down-regulates basal and osmolarity-induced gene expression of its transporter, but not the gene expression of its biosynthetic enzymes, in astrocyte primary cultures. J Neurochem. 2000;75:919–924. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0750919.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bock A, Krieger-Liszkay A, Beitia Ortiz de Zarate I, Schonknecht G. Cl- channel inhibitors of the arylaminobenzoate type act as photosystem II herbicides: a functional and structural study. Biochemistry. 2001;40:3273–3281. doi: 10.1021/bi002167a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branchini BR, Murtiashaw MH, Eckman EA, Egan LA, Alfano CV, Stroh JG. Modification of chloride ion transport in human erythrocyte ghost membranes by photoaffinity labeling reagents based on the structure of 5-nitro-2-(3-phenylpropylamino)-benzoic acid (NPPB) Arch Biochem Biophys. 1995;318:221–230. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1995.1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer GJ, Torricelli JR, Evege EK, Price PJ. Optimized survival of hippocampal neurons in B27-supplemented Neurobasal, a new serum-free medium combination. J Neurosci Res. 1993;35:567–576. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490350513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan-Palay V, Engel AG, Palay SL, Wu JY. Synthesizing enzymes for four neuroactive substances in motor neurons and neuromuscular junctions: light and electron microscopic immunocytochemistry. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1982;79:6717–6721. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.21.6717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesney RW, Jolly K, Zelikovic I, Iwahashi C, Lohstroh P. Increased Na+-taurine symporter in rat renal brush border membranes: preformed or newly synthesized? Faseb J. 1989;3:2081–2085. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.3.9.2744305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen ST, Voss JW, Teilmann SC, Lambert IH. High expression of the taurine transporter TauT in primary cilia of NIH3T3 fibroblasts. Cell Biol Int. 2005;29:347–351. doi: 10.1016/j.cellbi.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- d'Anglemont de Tassigny A, Souktani R, Ghaleh B, Henry P, Berdeaux A. Structure and pharmacology of swelling-sensitive chloride channels, I(Cl,swell) Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2003;17:539–553. doi: 10.1046/j.1472-8206.2003.00197.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deleuze C, Duvoid A, Hussy N. Properties and glial origin of osmotic-dependent release of taurine from the rat supraoptic nucleus. J Physiol. 1998;507(Pt 2):463–471. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.463bt.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dingledine R, Borges K, Bowie D, Traynelis SF. The glutamate receptor ion channels. Pharmacol Rev. 1999;51:7–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller CM, Ji HL, Tousson A, Elble RC, Pauli BU, Benos DJ. Ca(2+)-activated Cl(−) channels: a newly emerging anion transport family. Pflugers Arch. 2001;443(Suppl 1):S107–110. doi: 10.1007/s004240100655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant AC, Thomson J, Zammit VA, Shennan DB. Volume-sensitive amino acid efflux from a pancreatic beta-cell line. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2000;162:203–210. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(99)00260-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han X, Budreau AM, Chesney RW. Ser-322 is a critical site for PKC regulation of the MDCK cell taurine transporter (pNCT) J Am Soc Nephrol. 1999;10:1874–1879. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V1091874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haussinger D, Lang F, Gerok W. Regulation of cell function by the cellular hydration state. Am J Physiol. 1994;267:E343–355. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1994.267.3.E343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heisler S. Antagonists of epithelial chloride channels inhibit cAMP synthesis. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1991;69:501–506. doi: 10.1139/y91-075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heller-Stilb B, van Roeyen C, Rascher K, Hartwig HG, Huth A, Seeliger MW, Warskulat U, Haussinger D. Disruption of the taurine transporter gene (taut) leads to retinal degeneration in mice. Faseb J. 2002;16:231–233. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0691fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann EK. Intracellular signalling involved in volume regulatory decrease. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2000;10:273–288. doi: 10.1159/000016356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holopainen I, Malminen O, Kontro P. Sodium-dependent high-affinity uptake of taurine in cultured cerebellar granule cells and astrocytes. J Neurosci Res. 1987;18:479–483. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490180315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hruska RE, Padjen A, Bressler R, Yamamura HI. Taurine: sodium-dependent, high-affinity transport into rat brain synaptosomes. Mol Pharmacol. 1978;14:77–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huxtable RJ. Physiological actions of taurine. Physiol Rev. 1992;72:101–163. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1992.72.1.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson PS, Strange K. Volume-sensitive anion channels mediate swelling-activated inositol and taurine efflux. Am J Physiol. 1993;265:C1489–1500. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1993.265.6.C1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones DP, Miller LA, Chesney RW. Adaptive regulation of taurine transport in two continuous renal epithelial cell lines. Kidney Int. 1990;38:219–226. doi: 10.1038/ki.1990.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang YS, Ohtsuki S, Takanaga H, Tomi M, Hosoya K, Terasaki T. Regulation of taurine transport at the blood-brain barrier by tumor necrosis factor-alpha, taurine and hypertonicity. J Neurochem. 2002;83:1188–1195. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.01223.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimelberg HK. Current concepts of brain edema. Review of laboratory investigations. J Neurosurg. 1995;83:1051–1059. doi: 10.3171/jns.1995.83.6.1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klatzo I. Presidental address. Neuropathological aspects of brain edema. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1967;26:1–14. doi: 10.1097/00005072-196701000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kontro P, Oja SS. Taurine uptake by rat brain synaptosomes. J Neurochem. 1978;30:1297–1304. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1978.tb10459.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreisman NR, Olson JE. Taurine enhances volume regulation in hippocampal slices swollen osmotically. Neuroscience. 2003;120:635–642. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(03)00359-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson OM, Griffiths R, Allen IC, Schousboe A. Mutual inhibition kinetic analysis of gamma-aminobutyric acid, taurine, and beta-alanine high-affinity transport into neurons and astrocytes: evidence for similarity between the taurine and beta-alanine carriers in both cell types. J Neurochem. 1986;47:426–432. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1986.tb04519.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann A. Effects of microdialysis-perfusion with anisoosmotic media on extracellular amino acids in the rat hippocampus and skeletal muscle. J Neurochem. 1989;53:525–535. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1989.tb07365.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G, Olson JE. Extracellular ATP activates chloride and taurine conductances in cultured hippocampal neurons. Neurochem Res. 2004;29:239–246. doi: 10.1023/b:nere.0000010452.26022.a7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu QR, Lopez-Corcuera B, Nelson H, Mandiyan S, Nelson N. Cloning and expression of a cDNA encoding the transporter of taurine and beta-alanine in mouse brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:12145–12149. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.24.12145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loo DD, Hirsch JR, Sarkar HK, Wright EM. Regulation of the mouse retinal taurine transporter (TAUT) by protein kinases in Xenopus oocytes. FEBS Lett. 1996;392:250–254. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00823-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowry OH, Rosebrough NJ, Farr AL, Randall RJ. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951;193:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melton JE, Patlak CS, Pettigrew KD, Cserr HF. Volume regulatory loss of Na, Cl, and K from rat brain during acute hyponatremia. Am J Physiol. 1987;252:F661–669. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1987.252.4.F661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Militante JD, Lombardini JB. Taurine uptake activity in the rat retina: protein kinase C-independent inhibition by chelerythrine. Brain Res. 1999;818:368–374. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)01318-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagelhus EA, Lehmann A, Ottersen OP. Neuronal-glial exchange of taurine during hypo-osmotic stress: a combined immunocytochemical and biochemical analysis in rat cerebellar cortex. Neuroscience. 1993;54:615–631. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(93)90233-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson JE. Osmolyte contents of cultured astrocytes grown in hypoosmotic medium. Biochem Biophys Acta. 1999;1453:175–179. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4439(98)00090-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson JE, Holtzman D. Respiration in rat cerebral astrocytes from primary culture. J Neurosci Res. 1980;5:497–506. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490050605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson JE, Holtzman D. Factors influencing the growth and respiration of rat cerebral astrocytes in primary culture. Neurochem Res. 1981;6:1337–1343. doi: 10.1007/BF00964355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson JE, Li GZ. Increased potassium, chloride, and taurine conductances in astrocytes during hypoosmotic swelling. Glia. 1997;20:254–261. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-1136(199707)20:3<254::aid-glia9>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson JE, Li GZ. Osmotic sensitivity of taurine release from hippocampal neuronal and glial cells. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2000;483:213–218. doi: 10.1007/0-306-46838-7_23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson JE, Martinho E. 2003 Abstract Viewer and Itinerary Planner. Society for Neuroscience; Washington DC: 2003. Regulation of the taurine transporter in cultured hippocampal neurons. Program No.905.904. [Google Scholar]

- Olson JE, Martinho E. Taurine transporter regulation in hippocampal neurons. Adv Exp Biol Medicine. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-33504-9_34. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ordaz B, Vaca L, Franco R, Pasantes-Morales H. Volume changes and whole cell membrane currents activated during gradual osmolarity decrease in C6 glioma cells: contribution of two types of K+ channels. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2004;286:C1399–1409. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00198.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palacin M, Estevez R, Bertran J, Zorzano A. Molecular biology of mammalian plasma membrane amino acid transporters. Physiol Rev. 1998;78:969–1054. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1998.78.4.969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pappas CA, Ransom BR. Depolarization-induced alkalinization (DIA) in rat hippocampal astrocytes. J Neurophysiol. 1994;72:2816–2826. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.72.6.2816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasantes-Morales H, Moran J, Schousboe A. Volume-sensitive release of taurine from cultured astrocytes: properties and mechanism. Glia. 1990;3:427–432. doi: 10.1002/glia.440030514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasantes-Morales H, Maar TE, Moran J. Cell volume regulation in cultured cerebellar granule neurons. J Neurosci Res. 1993;34:219–224. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490340209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasantes-Morales H, Franco R, Ochoa L, Ordaz B. Osmosensitive release of neurotransmitter amino acids: relevance and mechanisms. Neurochem Res. 2002;27:59–65. doi: 10.1023/a:1014850505400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasantes Morales H, Schousboe A. Volume regulation in astrocytes: a role for taurine as an osmoeffector. J Neurosci Res. 1988;20:503–509. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490200415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plum F, Posner JB, Alvord EC. Edema and necrosis in experimental cerebral infarction. Arch Neurol. 1963;9:563–570. [Google Scholar]

- Poulsen KA, Litman T, Eriksen J, Mollerup J, Lambert IH. Downregulation of taurine uptake in multidrug resistant Ehrlich ascites tumor cells. Amino Acids. 2002;22:333–350. doi: 10.1007/s007260200019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pow DV, Sullivan R, Reye P, Hermanussen S. Localization of taurine transporters, taurine, and (3)H taurine accumulation in the rat retina, pituitary, and brain. Glia. 2002;37:153–168. doi: 10.1002/glia.10026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian X, Vinnakota S, Edwards C, Sarkar HK. Molecular characterization of taurine transport in bovine aortic endothelial cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1509:324–334. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(00)00315-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero MF, Boron WF. Electrogenic Na+/HCO3- cotransporters: cloning and physiology. Annu Rev Physiol. 1999;61:699–723. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.61.1.699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy G, Banderali U. Channels for ions and amino acids in kidney cultured cells (MDCK) during volume regulation. J Exp Zool. 1994;268:121–126. doi: 10.1002/jez.1402680208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Olea R, Moran J, Schousboe A, Pasantes-Morales H. Hyposmolarity-activated fluxes of taurine in astrocytes are mediated by diffusion. Neurosci Lett. 1991;130:233–236. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(91)90404-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Olea R, Morales M, Garcia O, Pasantes-Morales H. Cl channel blockers inhibit the volume-activated efflux of Cl and taurine in cultured neurons. Am J Physiol. 1996;270:C1703–1708. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1996.270.6.C1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholz WK, Baitinger C, Schulman H, Kelly PT. Developmental changes in Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II in cultures of hippocampal pyramidal neurons and astrocytes. J Neurosci. 1988;8:1039–1051. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.08-03-01039.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schousboe A, Fosmark H, Svenneby G. Taurine uptake in astrocytes cultured from dissociated mouse brain hemispheres. Brain Res. 1976;116:158–164. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(76)90258-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith KE, Borden LA, Wang CH, Hartig PR, Branchek TA, Weinshank RL. Cloning and expression of a high affinity taurine transporter from rat brain. Mol Pharmacol. 1992;42:563–569. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solis JM, Herranz AS, Herreras O, Lerma J, Martin del Rio R. Does taurine act as an osmoregulatory substance in the rat brain? Neurosci Lett. 1988;91:53–58. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(88)90248-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solis JM, Herranz AS, Herreras O, Menendez N, del Rio RM. Weak organic acids induce taurine release through an osmotic-sensitive process in in vivo rat hippocampus. J Neurosci Res. 1990;26:159–167. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490260205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stover JF, Unterberg AW. Increased cerebrospinal fluid glutamate and taurine concentrations are associated with traumatic brain edema formation in rats. Brain Res. 2000;875:51–55. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02597-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strange K, Morrison R, Shrode L, Putnam R. Mechanism and regulation of swelling-activated inositol efflux in brain glial cells. Am J Physiol. 1993;265:C244–256. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1993.265.1.C244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi K, Azuma M, Yamada T, Ohyabu Y, Schaffer SW, Azuma J. Taurine transporter in primary cultured neonatal rat heart cells: a comparison between cardiac myocytes and nonmyocytes. Biochem Pharmacol. 2003;65:1181–1187. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(03)00003-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamai I, Senmaru M, Terasaki T, Tsuji A. Na(+)- and Cl(−)-dependent transport of taurine at the blood-brain barrier. Biochem Pharmacol. 1995;50:1783–1793. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(95)02046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tchoumkeu-Nzouessa GC, Rebel G. Activation of protein kinase C down-regulates glial but not neuronal taurine uptake. Neurosci Lett. 1996;206:61–64. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(96)12426-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thinnes FP, Reymann S. New findings concerning vertebrate porin. Naturwissenschaften. 1997;84:480–498. doi: 10.1007/s001140050432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trachtman H, Barbour R, Sturman JA, Finberg L. Taurine and osmoregulation: taurine is a cerebral osmoprotective molecule in chronic hypernatremic dehydration. Pediatr Res. 1988;23:35–39. doi: 10.1203/00006450-198801000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verbalis JG, Gullans SR. Hyponatremia causes large sustained reductions in brain content of multiple organic osmolytes in rats. Brain Res. 1991;567:274–282. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)90806-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voss JW, Pedersen SF, Christensen ST, Lambert IH. Regulation of the expression and subcellular localization of the taurine transporter TauT in mouse NIH3T3 fibroblasts. Eur J Biochem. 2004;271:4646–4658. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.2004.04420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wade JV, Olson JP, Samson FE, Nelson SR, Pazdernik TL. A possible role for taurine in osmoregulation within the brain. J Neurochem. 1988;51:740–745. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1988.tb01807.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wangemann P, Wittner M, Di Stefano A, Englert HC, Lang HJ, Schlatter E, Greger R. Cl(−)-channel blockers in the thick ascending limb of the loop of Henle. Structure activity relationship. Pflugers Arch. 1986;407(Suppl 2):S128–141. doi: 10.1007/BF00584942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warskulat U, Wettstein M, Haussinger D. Osmoregulated taurine transport in H4IIE hepatoma cells and perfused rat liver. Biochem J. 1997;321(Pt 3):683–690. doi: 10.1042/bj3210683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warskulat U, Flogel U, Jacoby C, Hartwig HG, Thewissen M, Merx MW, Molojavyi A, Heller-Stilb B, Schrader J, Haussinger D. Taurine transporter knockout depletes muscle taurine levels and results in severe skeletal muscle impairment but leaves cardiac function uncompromised. Faseb J. 2004;18:577–579. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0496fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasterlain CG, Torack RM. Cerebral edema in water intoxication. II. An ultrastructural study. Arch Neurol. 1968;19:79–87. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1968.00480010097008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wersinger C, Rebel G, Lelong-Rebel IH. Characterisation of taurine uptake in human KB MDR and non-MDR tumour cell lines in culture. Anticancer Res. 2001;21:3397–3406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright CE, Tallan HH, Lin YY, Gaull GE. Taurine: biological update. Annu Rev Biochem. 1986;55:427–453. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.55.070186.002235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xin WK, Kwan CL, Zhao XH, Xu J, Ellen RP, McCulloch CA, Yu XM. A functional interaction of sodium and calcium in the regulation of NMDA receptor activity by remote NMDA receptors. J Neurosci. 2005;25:139–148. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3791-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang ZR, Zeltwanger S, McCarty NA. Direct comparison of NPPB and DPC as probes of CFTR expressed in Xenopus oocytes. J Membr Biol. 2000;175:35–52. doi: 10.1007/s002320001053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]