Abstract

Assisted reproductive technologies (ARTs) have now contributed to the birth of >3 million babies worldwide, but concerns remain regarding the safety of these methods. We have used a transgenic mouse model to examine the effects of ARTs on the frequency and spectrum of point mutations in midgestation mouse fetuses produced by either natural reproduction or various methods of ART, including preimplantation culture, embryo transfer, in vitro fertilization, intracytoplasmic sperm injection, and round spermatid injection. Our results show that there is no significant difference in the frequency or spectrum of de novo point mutations found in naturally conceived fetuses and fetuses produced by in vitro fertilization, intracytoplasmic sperm injection, or round spermatid injection. These results, based on analyses of a transgenic mouse system, indicate that with respect to maintenance of genetic integrity, ARTs appear to be safe.

Keywords: genetic integrity, in vitro fertilization, infertility, mutagenesis, embryology

Since the birth in 1978 of Louise Brown, the first successful “test-tube baby” conceived by in vitro fertilization (IVF) (1), it is estimated that >3 million babies have been born through the application of some form of assisted reproductive technology (ART) (www.medicalnewstoday.com/medicalnews.php?newsid = 45720). ARTs have provided novel solutions to the treatment of hundreds of thousands of otherwise infertile couples worldwide. The advent of embryo transfer (2, 3), intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) (4), microsurgical procedures for testicular sperm extraction (5, 6), and round spermatid injection (ROSI) (7) has further expanded the scope of infertile conditions for which ARTs now provide treatment. As a result, these methodologies are now responsible for 1–2% of births in most western countries (8, 9) and as much as 6% of births in certain countries such as Denmark (10). This figure is likely to continue to increase with ongoing technical advances in methods of ART and demographic changes in the population of individuals seeking treatment for infertility.

Despite the remarkable successes of ARTs, there remain concerns about the safety of these methodologies. Previous studies have indicated an association between ARTs and potential disruption of epigenetic programming as indicated by a higher than average incidence of ART-derived children included among registries of diseases associated with defects in genomic imprinting such as Angelman syndrome (11), Beckwith–Weidemann syndrome (12–14), and retinoblastoma (15). In addition, studies in mice have demonstrated that culture of preimplantation embryos in the presence of serum is associated with increased abnormalities in expression of imprinted genes (16, 17) and disturbances in fetal development leading to small offspring (17, 18), as well as an increased incidence of certain behavioral abnormalities (19).

One area of potential concern that has not been thoroughly investigated is the possibility that the use of ARTs could introduce de novo genetic aberrations that would be manifested as an increase in the frequency and/or a change in the spectrum of mutations in the resulting offspring. Previous studies have yielded inconsistent evidence of any increased risk of karyotypic abnormalities in ART-derived children other than that normally associated with the age or other predisposing histories of the parents (20, 21). A study of human embryos by Munne et al. (22) concluded that ICSI does not produce more numerical chromosomal abnormalities than conventional IVF. In a study of mouse embryos, Bean et al. (23) found that alterations in culture conditions may have considerable impact on the genetic quality of embryos derived by ART. However, a karyotype reveals only the grossest of genetic aberrations, including abnormalities in ploidy or very large deletions, duplications, or rearrangements of chromosomal material. This excludes any assessment of the most common genetic aberrations, collectively known as point mutations, including single base substitutions, or small deletions, insertions, or rearrangements. Point mutations are estimated to be responsible for a majority of genetic diseases in humans (24) and, as such, represent a class of mutations that clearly warrants investigation.

A global analysis of point mutations in human ART-derived offspring is impractical because de novo mutations at any one site typically occur at a frequency of only 1 in 10,000–1,000,000 genomes (25). We therefore used a transgenic mouse model designed specifically to facilitate an analysis of the frequency and spectrum of rare point mutations. The Big Blue transgenic mouse from Stratagene (La Jolla, CA) carries as an integrated transgene, a lambda bacteriophage shuttle vector that can be selectively recovered from genomic DNA, packaged into infectious phage particles and screened by a colorimetric assay to detect rare mutant copies of the bacterial lacI gene within a background of largely nonmutated copies of this gene (26). In addition, phage DNA carrying a mutant transgene can be amplified and sequenced to determine the exact change in base sequence that constitutes any individual mutation. Using this approach, the reporter transgene can be examined to determine both the frequency and spectrum of point mutations. We have used this system to determine whether ART-based methods of reproduction introduce any relative differences in the frequency or spectrum of point mutations in midgestation fetuses compared with those found in fetuses produced by natural reproduction.

Results

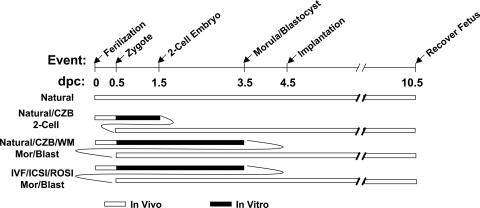

To determine the normal frequency of de novo mutations in midgestation mouse fetuses, we recovered DNA from transgenic fetuses produced by natural conception and natural gestation [i.e., endogenous fetuses recovered directly from uteri at 10.5 days post coitum (dpc)] and measured the frequency of mutations in the lacI reporter transgene. To examine the effects of in vitro culture of preimplantation embryos plus embryo transfer on the frequency of mutations in resulting fetuses, we allowed mice to mate naturally, recovered the fertilized oocytes at the pronuclear stage, and cultured these to either the two-cell stage or the morula/blastocyst stage in either Chatot, Ziomet, and Bavister (CZB) (27) or Whitten's media (28). CZB media is a media commonly used for ART and cloning procedures involving murine cells. Whitten's media was previously reported to lead to an increased frequency of epigenetic aberrations in cultured embryos (17, 19). We then transferred cultured embryos at either the two-cell or morula/blastocyst stage into surrogate dams, recovered midgestation fetuses at 10.5 dpc, and determined the frequency of mutations in each case. To determine the effects of conception by IVF, ICSI, or ROSI on mutation frequency or spectrum, we followed the same scheme, except that we generated zygotes in vitro using gametes recovered from adult male or female mice. The overall developmental scheme for each category of embryos/fetuses produced is summarized in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Developmental scheme for each type of embryo/fetus. A timeline of development to the midgestation stage (10.5 dpc) is shown along with a schematic representation of relative portions of development in vivo (white bar) and in vitro (black bar) for each type of reproduction examined. Control fetuses were produced by natural mating plus natural endogenous gestation (Natural). Test fetuses were produced by natural mating followed by recovery and in vitro culture in CZB to the two-cell stage (Natural/CZB 2-Cell) or the morula/blastocyst stage in either CZB media (Natural/CZB Mor/Blast) or Whitten's media (Natural/WM Mor/Blast), or fetuses were produced by IVF, ICSI, or ROSI fertilization, followed in each case by culture to the morulat/blastocyst stage, embryo transfer, and subsequent development in vivo to midgestation (10.5 dpc). Because implantation of mouse embryos occurs at 4.5 dpc regardless of the stage of embryos transferred, a curved line is used in this figure to show the overlap period between portions of development in vitro and in vivo.

Naturally conceived and gestated fetuses showed a frequency of de novo mutations of 1.08 ± 0.15 (×10−5). Natural conception followed by preimplantation culture to the two-cell or morula/blastocyst stage followed by embryo transfer yielded 10.5 dpc fetuses that showed no statistically significant differences in the frequency of de novo mutations compared with the naturally conceived and developed fetuses (P = 0.4766) (Table 1). This indicates that neither preimplantation culture nor embryo transfer is normally mutagenic.

Table 1.

Mutant frequencies in midgestation fetuses

| Method of conception | Culture media | Stage at transfer | No. of fetuses | Total no. of pfu | No. of mutant plaques* | Conf. ind. mutants† | Mut. freq.± SE (× 10−5)‡ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Natural | None | n/a | 15§ + 5¶ | 4,642,208 | 59 | 50 | 1.08 ± 0.15 |

| Natural | CZB | Mor/Blast | 15§ | 2,418,751 | 23 | 21 | 0.87 ± 0.19 |

| Natural | CZB | two-cell | 15§ | 2,339,815 | 31 | 31 | 1.32 ± 0.24 |

| Natural | WM | Mor/Blast | 15§ | 2,774,900 | 33 | 33 | 1.19 ± 0.21 |

| IVF | CZB | Mor/Blast | 5¶ | 2,210,684 | 22 | 21 | 0.95 ± 0.21 |

| ICSI | CZB | Mor/Blast | 5¶ + 16‖ | 8,081,035 | 106 | 85 | 1.05 ± 0.11 |

| ROSI | CZB | Mor/Blast | 5¶ | 2,312,684 | 24 | 23 | 0.99 ± 0.21 |

Mor, morula; Blast, blastocyst.

*Total mutant plaques recovered.

†Conf. ind mutants, confirmed independent mutants [total mutants recovered minus potential “jackpot mutants” (see Methods)].

‡Mutation frequency based on confirmed independent mutants.

§Three fetuses each from five different parental pairs.

¶One fetus each from five different parental pairs.

‖Sixteen additional fetuses from three different parental pairs.

We next examined the frequency of de novo mutations in fetuses produced by either IVF, ICSI, or ROSI followed by culture to the morula/blastocyst stage, transfer into surrogate dams, and gestation to 10.5 dpc. We initially examined five individual fetuses from each of the ART groups (IVF, ICSI, and ROSI) and found a higher initial frequency of mutants in the ICSI group. However, upon sequencing the mutant lacI transgenes from each group of fetuses and adjusting for jackpot mutations to yield confirmed independent mutations in each group (see Analysis of Mutation Spectrum in Methods), we found no significant difference between the frequency of mutations in the ICSI group and that in any other group including the naturally conceived and gestated fetuses. Nevertheless, to further confirm that production of embryos by ICSI does not typically introduce more mutations than any other mode of reproduction, we analyzed an additional 16 individual ICSI fetuses derived from three different pairs of sperm + oocyte donors. The data from all 21 ICSI-derived fetuses are presented in Table 1.

The frequency of de novo mutations in fetuses produced by IVF was 0.95 ± 0.21 (×10−5), that in fetuses produced by ICSI was 1.05 ± 0.11 (×10−5), and that in fetuses produced by ROSI was 0.99 ± 0.21 (×10−5) (Table 1). There were no statistically significant differences in frequencies of de novo mutations among naturally conceived and gestated fetuses and fetuses produced by IVF, ICSI, or ROSI (Table 1, P = 0.9609). This indicates that these methods of in vitro conception are not mutagenic. We further compared the frequency of occurrence of jackpot mutations in individual ICSI-derived fetuses and individual naturally conceived and gestated fetuses and found no apparent difference in the incidence of jackpot mutations in the two groups (data not shown).

We then sequenced each of the mutant lacI genes recovered from fetuses in each category to confirm that a genetic mutation had indeed occurred in each case and to determine the spectrum of mutations associated with each mode of reproduction. The Big Blue transgenic system readily reveals point mutations, including base substitutions (transitions or transversions) or small insertions or deletions. A summary of the results of this analysis is shown in Table 2. There were no statistically significant differences in the mutation spectra among naturally conceived and gestated fetuses and fetuses produced by either IVF, ICSI, or ROSI (P ≥ 0.1138). Thus the use of these ART procedures did not alter either the frequency or spectrum of point mutations in resultant fetuses. A detailed listing of each individual mutation is provided in supporting information (SI) Table 3.

Table 2.

Mutation spectra in midgestation fetuses

| Mutation type | Natural* | Nat-CZB† two-cell‡ | Nat-CZB† Mor/Blast§ | Nat-WM¶ Mor/Blast | IVF-CZB‖ Mor/Blast | ICSI-CZB** Mor/Blast | ROSI-CZB†† Mor/Blast |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transition, % | 37 (74) | 21 (68) | 14 (67) | 21 (64) | 10 (48) | 63 (74) | 14 (61) |

| Transversion, % | 4 (8) | 5 (16) | 7 (33) | 7 (21) | 5 (24) | 11 (13) | 4 (17) |

| Ins/Del, % | 6 (12) | 3 (10) | 0 | 3 (9) | 3 (14) | 8 (9) | 3 (13) |

| DBS, % | 3 (6) | 1 (3) | 0 | 2 (6) | 2 (10) | 2 (2) | 2 (9) |

| Other, % | 0 | 1 (3) | 0 | 0 | 1 (5) | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Total | 50 | 31 | 21 | 33 | 21 | 85 | 23 |

DBS, double base substitution; Ins, insertion; Del, deletion; Other, combination of simultaneous deletion and insertion. For a complete list of individual muations (sequence change and location) in all categories, see SI Table 3.

*Natural conception plus natural gestation.

†Natural conception plus preimplantation culture in CZB media.

‡Embryo transfer at two-cell stage.

§Embryo transfer at morula/blastocyst stage.

¶Natural conception plus preimplantation culture in Whitten's media.

‖Conception by IVF plus preimplantation culture in CZB media.

**Conception by ICSI plus preimplantation culture in CZB media.

††Conception by ROSI plus preimplantation culture in CZB media.

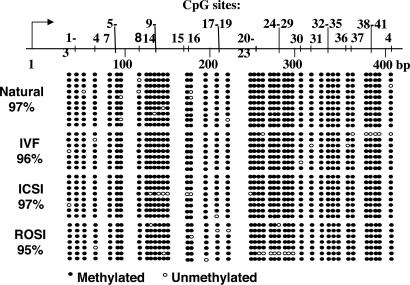

Transitions were the predominant type of point mutation detected in all groups, as is the case with naturally occurring spontaneous mutations in most mammalian species, including humans (29). A common mechanism leading to transition mutations in mammalian DNA is deamination of methylated cytosines to form thymines, resulting in C/G-to-T/A transitions (30). Cytosines present in a 5′-CpG-3′ dinucleotide are the only bases in mammalian DNA that are normally found methylated in vivo, but only a portion of cytosines in CpG dinucleotides are methylated in any particular cell type at any one time (31, 32). To determine whether the high proportion of transition mutations we observed in the lacI transgene in midgestation fetuses was correlated with hypermethylation of this gene, we performed bisulfite genomic sequencing on 10.5 dpc fetuses produced by each mode of reproduction. The results of this analysis show that this transgene was indeed heavily methylated in all groups of fetuses tested (Fig. 2), indicating ample opportunity for the generation of de novo transition mutations by deamination of cytosines.

Fig. 2.

DNA methylation in the lacI transgene. Bisulfite genomic sequencing was used to assess the extent of DNA methylation in the lacI transgene in 10.5 dpc fetuses generated by natural mating + natural development (natural), IVF, ICSI, and ROSI. In each case, 7–10 different PCR amplicons were examined. The map at the top of the figure shows the location of 42 CpG sites within the region encoding the DNA-binding domain relative to the transcriptional start site (bent arrow) in the lacI transgene. Filled circles indicate methylated cytosines, and open circles indicate unmethylated cytosines. In all cases, the transgene was heavily methylated (95–97%).

Discussion

An ongoing concern about the use of ARTs has been the extent to which these procedures might disrupt naturally occurring processes, especially processes associated with dynamic reprogramming required to direct proper embryonic and fetal development. Dynamic changes in epigenetic programming normally occur in the male and female germ-line genomes during gametogenesis and in the resulting embryonic genome extending throughout fetal development. Evidence that ARTs may disrupt epigenetic programming mechanisms has been reported (11–19). In addition, however, there are also changes in genetic parameters during reproduction, specifically in the frequency of acquired mutations in germ cells and embryos. It has been shown that mature spermatozoa carry 5- to 10-fold fewer acquired mutations than do somatic cells from the same individual (33), and preliminary results indicate a similar discrepancy in the frequency of mutations in germ cells and somatic cells in females (P.M. and J.R.M., data not shown). The low frequency of acquired mutations transmitted by the gametic genomes yields an initial embryonic genome with a similarly low frequency of mutations. However, as development proceeds, there is a relatively rapid accumulation of de novo mutations as evidenced by our finding of a mutation frequency of ≈1 (×10−5) in naturally conceived and gestated fetuses at 10.5 dpc.

In the study described here, we have investigated the effects of a variety of different types of assisted reproductive technologies on the frequency and spectrum of point mutations in resulting fetuses. This analysis was necessarily conducted in an animal model system because no similar analysis is feasible in human subjects. Further, this study had the advantage of being designed as a prospective, experimental analysis of a fully fertile population, thus eliminating the variables of infertility or subfertility that often confound human case studies. There are several aspects of ARTs that could be mutagenic. These include direct effects of physical manipulations of gametes and embryos and/or effects of the ex vivo environment in which these manipulations are performed. By comparing the frequency of mutations in midgestation fetuses derived from natural conception and gestation with that in fetuses produced by natural mating followed by culture in vitro for a portion of the preimplantation period and subsequent transfer into surrogate females to foster development to the midgestation stage, we found that these procedures do not lead to any increase in the occurrence of de novo point mutations. This indicates that the mechanisms that normally maintain genetic integrity in preimplantation embryos (e.g., DNA repair activities) function similarly in embryos that are maintained in the female tract during normal development or in culture during in vitro development. These results further indicate that maintenance of genetic integrity is more stringent than maintenance of epigenetic integrity in mammalian embryos cultured in vitro because we observed no defects in the former, whereas defects in the latter have been reported (11–19).

Conception in vitro affords additional opportunities for mutagenesis because of manipulations of gametes required for each method. Both ICSI and ROSI require the use of unique physical manipulations that could damage the spermatozoon or spermatid, respectively, as well as the oocyte into which these are injected. This could lead to disruption of subcellular compartmentalization of nucleic acids or other cellular components including nucleases that could cause mutations if afforded access to genomic DNA. Alternatively, such manipulations could have secondary mutagenic effects by leading to changes in intracellular ion concentrations that could activate endogenous nucleases or repress endogenous DNA repair activities in gametes or embryos. However our analysis of midgestation fetuses produced by IVF, ICSI, or ROSI indicates that these methods do not alter either the frequency or spectrum of point mutations in resulting fetuses.

We did observe differences in the proportions of transferred embryos that survived to midgestation generated by each method of ART. As a result, an expanded study of the differential developmental efficiencies associated with various ART procedures is now underway (Y.Y, L.C., R.Y., and J.R.M., data not shown). However, for the purpose of the present study, we focused on mutation frequencies in viable fetuses at 10.5 dpc because a high proportion of fetuses that survive to midgestation typically proceed to term, and it was specifically for this category of fetuses that we wished to assess any potential contribution of ART methodologies to mutagenesis.

In theory, a disruption of epigenetic programming could lead to a subsequent mutagenic event either by imparting a change in the status of methylation of cytosines that could lead to a change in the frequency of C/G-to-T/A transitions or by disrupting the regulation of DNA repair genes that are critical for normal maintenance of genetic integrity. However, we observed no such alterations in genetic integrity in fetuses produced by ARTs. This includes the absence of any effects of culturing preimplantation embryos in Whitten's media, which was previously shown to disrupt epigenetic programming to some extent (17, 19).

With respect to assessments of genetic integrity, it is important to distinguish between inherited and de novo mutations. Genetic defects extant in the germ-line genome of either parent are equally likely to be propagated to offspring as inherited mutations by natural or assisted reproduction (34). Our study was specifically focused on assessing the incidence of newly acquired, de novo mutations to determine whether ART procedures directly generate new point mutations. We found that de novo point mutations normally occur at a relatively low frequency in midgestation fetuses produced by natural conception and gestation, and our analysis of fetuses produced by IVF, ICSI, or ROSI shows that the frequency and spectrum of these mutations is unchanged as a result of the application of ART procedures. Thus we conclude that with respect to the maintenance of genetic integrity, as indicated by the frequency or spectrum of de novo point mutations, methods of ART appear to be safe.

Methods

Mice.

All procedures involving live animals were approved in advance by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Hawaii. “Big Blue” females (Stratagene) homozygous for the lacI transgene on a C57BL/6 background (26) were used for natural mating and as a source of mature unfertilized oocytes. Wild-type (nontransgenic) DBA/2 males (NCI) were used for natural mating and as a source of spermatozoa and round spermatids. Wild-type CD-1 females (Charles River) previously mated with vasectomized males of the same strain served as surrogate mothers. All animals were maintained in air-conditioned rooms with regulated light-dark cycles (14 h light/10 h dark, starting from 6:00 a.m. each day).

Media.

Bicarbonate-buffered CZB medium supplemented with glucose (27) or Whitten's medium supplemented with EDTA (WM) (29) was used for culture of embryos at 37°C in 5% CO2 in air. Manipulation of oocytes was carried out in Hepes-buffered CZB (Hepes-CZB) (33) at room temperature (23°C) in 100% air. TYH medium (36) was used for sperm capacitation and fertilization in vitro.

Natural Mating and Culture of Naturally Fertilized Embryos in Vitro.

“Big Blue” females in spontaneous estrus were mated with DBA/2 males. The day following mating (= day of vaginal plug) was considered day 0.5 of pregnancy. Fertilized oocytes that had reached the pronuclear stage were collected from the oviducts on the day following natural mating and cultured in CZB for 1 day to obtain 2-cell embryos, or cultured in either CZB or WM for 3 days to obtain morula/blastocyst embryos.

In Vitro Manipulations of Gametes or Embryos.

For IVF, spermatozoa collected from the cauda epididymides of adult DBA/2 male mice were incubated for 1–2 h in TYH medium. A small volume of capacitated sperm suspension was added to a drop of TYH medium containing freshly ovulated oocytes as described (35). Four to five hours later, fertilized oocytes at the pronuclear stage were washed and cultured in CZB with glucose for 1–3 days in 5% CO2 in air 4–5 hours later; 10–20 embryos were cultured together in one drop of media. ICSI and ROSI were performed as described by Kimura and Yanagimachi (36, 37), except that isolated sperm heads, instead of entire spermatozoa, were injected into oocytes during ICSI (38), and oocytes used for ROSI were activated by a 4–5 h treatment with 10 mM SrCl2 in Ca- and Mg-free CZB medium.

Embryo Transfer.

Embryos at the 2-cell or morula/blastocyst stages were transferred into the oviducts of females rendered pseudopregnant by mating to vasectomized males the night preceding embryo transfer; 5–7 embryos were transferred into one oviduct of each recipient female. The day of transfer was considered day 0.5 of pregnancy because implantation of mouse embryos occurs at 4.5 dpc regardless of the stage of embryos transferred. Transferred embryos were subsequently recovered from uteri of surrogate dams at 10.5 dpc.

Experimental Design.

For each method of conception, embryos or fetuses were collected from five separate parental pairs. In each case, the sire was from the DBA2 strain, whereas the dam was from the C57BL/6 strain carrying the lacI transgene. Except where otherwise noted, an equal number of embryos were analyzed from each parental pair. A minimum of 2 million plaque-forming units (pfu) were examined for each category based on calculations conducted before initiating these experiments, indicating this number would yield a power of 0.80 to detect a 2-fold change in mutation frequencies from a baseline frequency of 1.2 × 10−5. Midgestation fetuses were examined because this is the earliest stage following fertilization that could provide sufficient numbers of cells, and hence sufficient numbers of pfu, to facilitate this analysis on individual fetuses. Later stages were not examined because we wanted to focus this analysis on the immediate effects of methods of conception and/or manipulations during preimplantation stages to the greatest extent possible.

Recovery of High-Molecular-Weight DNA.

High-molecular-weight genomic DNA was isolated from 10.5 dpc fetuses of normal size and morphology by using the RecoverEase DNA isolation kit according to the manufacturer's recommendations (Stratagene) with the following modifications. Each frozen fetus was resuspended in 50 μl of ice-cold lysis buffer and transferred to a 2-ml Kontes (Vineland, NJ) dounce tissue homogenizer and homogenized slowly with plunger “B” ≈5 times and then 5 more times with plunger “A.” The homogenate was transferred to a 1.5-ml microcentrifuge tube fitted with a 100 μm Millipore (Billerica, MA) filter and spun briefly to filter the homogenate. After removal of the filter, the tube was centrifuged at 13,200 rpm for 15 min at 4°C, the supernatant was removed, and the pellet was resuspended in 10 μl RNace-it (Stratagene) ribonuclease mixture (1 μl RNace-it/49 μl digestion buffer) and incubated at 50°C for 5 min; 20 μl of proteinase K solution (2.0 mg/ml prewarmed to 50°C) was then added to the tube followed by incubation at 50°C for ≈1.5 h. Then 50 μl of 1× TE was added to each sample followed by drop dialysis by using a 0.025-μm Millipore dialysis membrane floating on 500 ml of 1× TE [0.01 M Tris·HCl + 0.1 M EDTA (pH 8.0)] for 2 days at room temperature.

Analysis of Mutation Frequency.

The lambda shuttle vector containing the lacI target was recovered from genomic DNA by using Transpack packaging extract (Stratagene) according to manufacturer's instructions. Packaged phage were mixed with SCS-8 E. coli cells (Stratagene) and plated at ≤17,500 pfu per 25 × 25 cm NZY agar assay tray. Following incubation at 37°C for 16–18 h, mutant plaques were identified by their blue color, counted, cored, and replated on fresh X-gal/NZY plates to confirm and purify phage displaying the lacI mutant phenotype. A minimum of three separate aliquots of DNA were packaged and analyzed from each individual fetus or pool of fetuses. A minimum of 300,000 pfus were screened for each sample of DNA, and a minimum of 2 million pfus were analyzed for each method of reproduction. After adjustment for “jackpot mutations” (see explanation below), the final mutation frequency was determined by dividing the number of confirmed, independent mutant plaques by the total number of plaque-forming units.

Analysis of Mutation Spectrum.

Isolated mutant phage samples were sent to the CBR DNA Sequencing Facility, University of Victoria, Canada, for sequence analysis. In each case, a 15-μl aliquot of phage stock (cored mutant plaque stored in SM buffer) was used as a template for PCR amplification of a 2,114-bp fragment including the lacI gene [primers: lacI AF (−285 to −259), 5′-AACGCCTGGTATCTTTATAGTCCTGTC-3′; and lacI AR (1829 to 1808), 5′-TCCAGATAACTGCCGTCACTCC-3′]. Each PCR product was sequenced by using a LI-COR Long ReadIR 4200 DNA sequencer by cycle sequencing [primers: lacI SF (−243 to −211), 5′-TGACTTGAGCGTCGATTTTTGTGC-3′ (IRDye700 labeled); and lacI SR (1344 to 1328), 5′-CCAGCTGGCGAAAGGGG-3′ (IRDye800 labeled)] by using the SequiTherm EXCEL II DNA Sequencing Kit-LC (Epicentre, Madison, WI) according to manufacturer's instructions. The sequence was analyzed by using e-Seq v3.0 base-calling software (LI-COR, Lincoln, NE) and SeqMan II v6.1 analysis software (DNAStar, Madison, WI).

A comparison of the lacI gene sequence in mutant phage with that of the wild-type lacI gene sequence revealed and confirmed each individual mutation. Mutations were categorized as transitions (pyrimidine-to-pyrimidine or purine-to-purine substitutions), transversions (pyrimidine-to-purine subsitution or vice versa), or small insertions or deletions.

In addition to providing mutation spectrum data, sequencing each mutant phage also allowed us to identify “jackpot” mutations. Jackpot mutations are those that are detected more than once in the same sample (i.e., the same change in base sequence at the same position) (39–41). Assuming random occurrence of mutations and given the typical frequency of de novo mutations, it is highly unlikely that the same mutation would occur independently more than once in the same sample tissue because the frequency of such an occurrence would be described by the product of the frequencies of a single mutation. Thus, when the same mutation is detected more than once in a single sample, it is assumed that the mutation occurred early in the development of that tissue and was subsequently propagated to a relatively large portion of the cells in the tissue, and this is termed a jackpot mutation (39–41). Such mutations were counted as a single confirmed independent mutation regardless of the number of times they were recovered from a single fetus (39, 42–44).

Statistical Analysis.

Mutation frequency data were analyzed by a Poisson regression model with parameter estimates obtained by the method of maximum likelihood (45). Statistical tests of differences used the likelihood ratio test. All computations were carried out by using SAS PROC GENMOD software (version 9.1; SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Mutation spectrum data were analyzed by using a χ2 test for independence. Because of low expected frequencies, the exact P value was calculated (using SAS version 9.1).

Analysis of DNA Methylation.

Bisulfite conversion of 2-μg genomic DNA from each fetus was performed by using the EZ DNA Methylation Kit (Zymo Research, Orange, CA) according to manufacturer's instructions. Bisulfite-converted genomic DNA was then amplified by PCR (primers: bislacIF, 5′-AGAGAGTTAATTTAGGGTGGTGAA-3′; and bislacIR, 5′-ACAACTTCCACAACAATAACATC-3′), and the products were cloned into the Topo T/A cloning vector (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to manufacturer's instructions. Seven to ten white bacterial colonies representing unique copies of the target gene were recovered and analyzed by preparing plasmid DNA by using the Wizard SV minipreps kit (Promega, Madison, WI) and sequencing the region of the lacI gene that includes the DNA-binding domain (+4 to +444) and contains 42 CpG sites (46, 47) on an ABI 3100 Avant sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) following manufacturer's instructions. The methylation status of each CpG dinucleotide was determined by comparison of sequences from bisulfite-converted and untreated DNA.

Supporting Information.

See SI Table 3, in which the specific location and change in base sequence for each mutation in the lacI gene are listed.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank E. Low, A. Isenor, and R. Martinez for technical assistance; and R. Brzyski for reading the manuscript and providing helpful comments. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant HD 42772 and American Association of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Foundation Grant 117221.

Abbreviations

- CZB

Chatot, Ziomet, and Bavister

- IVF

in vitro fertilization

- ART

assisted reproductive technology

- ICSI

intracytoplasmic sperm injection

- ROSI

round spermatid injection

- dpc

days post coitum

- pfu

plaque-forming unit.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0611642104/DC1.

References

- 1.Steptoe PC, Edwards RG. Lancet. 1978;2:366. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(78)92957-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balmaceda JP, Gastaldi C, Remohi J, Borrero C, Ord T, Asch RH. Fertil Steril. 1988;50:476–479. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)60136-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tan SL, Bennett S, Parsons J. Br Med Bull. 1990;46:628–642. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a072421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van Steirteghem AC, Nagy Z, Joris H, Liu J, Staessen C, Smitz J, Wisanto A, Devroey P. Hum Reprod. 1993;8:1061–1066. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a138192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nagy Z, Liu J, Cecile J, Silber S, Devroey P, Van Steirteghem A. Fertil Steril. 1995;63:808–815. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)57486-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Silber SJ, Van Steirteghem AC, Liu J, Nagy Z, Tournaye H, Devroey P. Hum Reprod. 1995;10:148–152. doi: 10.1093/humrep/10.1.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tesarik J, Mendoza C, Testart J. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:525. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199508243330819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schultz RM, Williams CJ. Science. 2002;296:2188–2190. doi: 10.1126/science.1071741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Center for Disease Control. Assisted Reproductive Technology (ART) Report. 2003.

- 10.Andersen AN, Erb K. Int J Androl. 2006;29:12–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.2005.00577.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cox GF, Burger J, Lip V, Mau UA, Sperling K, Wu BL, Horsthemke B. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;71:162–164. doi: 10.1086/341096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DeBaun MR, Niemitz EL, Feinberg AP. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;72:156–160. doi: 10.1086/346031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maher ER, Brueton LA, Bowdin SC, Luharia A, Cooper W, Cole TR, Macdonald F, Sampson JR, Barratt CL, Reik W, Hawkins MM. Med Genet. 2003;40:62–64. doi: 10.1136/jmg.40.1.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gicquel C, Gaston V, Mandelbaum J, Siffroi JP, Flahault, Le Bouc AY. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;72:1338–1341. doi: 10.1086/374824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moll AC, Imhof SM, Schouten-van Meeteren AY, Boers M, van Leeuwen F, Hofman P. Lancet. 2003;361:1392. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13065-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lucifero D, Chaillet JR, Trasler JM. Hum Reprod. 2004;10:3–18. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmh002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mann MR, Lee SS, Doherty AS, Verona RI, Nolen LD, Schultz RM, Bartolomei MS. Development (Cambridge, UK) 2004;131:3727–3735. doi: 10.1242/dev.01241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khosla S, Dean W, Brown D, Reik W, Feil R. Biol Reprod. 2001;64:918–926. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod64.3.918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ecker DJ, Stein P, Xu Z, Williams CJ, Kopf GS, Bilker WB, Abel T, Schultz RM. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:1595–1600. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0306846101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bonduelle M, Van Assche E, Joris H, Keymolen K, Devroey P, Van Steirteghem A, Liebaers I. Hum Reprod. 2002;17:2600–2614. doi: 10.1093/humrep/17.10.2600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aboulghar H, Aboulghar M, Mansour R, Serour G, Amin Y, Al-Inany H. Fertil Steril. 2001;76:249–253. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(01)01927-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Munne S, Marquez C, Reing A, Garrisi J, Alikani M. Fertil Steril. 1998;69:904–908. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(98)00039-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bean CJ, Hassold TJ, Judis L, Hunt PA. Human Reprod. 2002;17:2362–2367. doi: 10.1093/humrep/17.9.2362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Crow JF. Nat Rev Genet. 2000;1:40–47. doi: 10.1038/35049558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vogel F, Rathenberg R. Adv Hum Genet. 1975;4:223–318. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-9068-2_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kohler SW, Provost GS, Fieck A, Dretz PL, Bullock WO, Sorge JA, Putman DL, Short JM. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:7958–7962. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.18.7958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chatot CL, Lewis JL, Torres I, Ziomek CA. Biol Reprod. 1990;42:432–440. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod42.3.432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abramczuk J, Solter D, Koprowski H. Dev Biol. 1977;61:378–383. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(77)90308-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cooper DN, Krawczak M. Hum Genet. 1990;85:55–74. doi: 10.1007/BF00276326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Walsh CP, Xu GL. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2006;301:283–315. doi: 10.1007/3-540-31390-7_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lande-Diner L, Cedar H. Nat Rev Genet. 2005;6:648–654. doi: 10.1038/nrg1639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jaenisch R, Bird A. Nat Genet Suppl. 2003;33:245–254. doi: 10.1038/ng1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.The Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Fertil Steril. 2004;82(Suppl 1):S151–S152. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2004.05.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Walter CA, Intano GW, McCarrey JR, McMahan CA, Walter RB. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:10015–10019. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.17.10015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Toyoda Y, Yokoyama M, Hoshi T. Jpn J Anim Reprod. 1971;16:147–151. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kimura Y, Yanagimachi R. Biol Reprod. 1995;52:709–720. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod52.4.709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kimura Y, Yanagimachi R. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1995;121:2397–2405. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.8.2397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kuretake S, Kimura Y, Hoshi K, Yanagimachi R. Biol Reprod. 1996;55:789–795. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod55.4.789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nishino H, Schaid DJ, Buettner VL, Haavik J, Sommer SS. Environ Mol Mutagen. 1996;28:414–417. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2280(1996)28:4<414::AID-EM16>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Heddle JA. Mutagenesis. 1999;14:257–260. doi: 10.1093/mutage/14.3.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hill KA, Buettner VL, Glickman BW, Sommer SS. Mutat Res. 1999;436:11–19. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5742(98)00024-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nishino H, Buettner VL, Haavik J, Schaid DJ, Sommer SS. Environ Mol Mutagen. 1996;28:299–312. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2280(1996)28:4<299::AID-EM2>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hill KA, Buettner VL, Halangoda A, Kunishige M, Moore SR, Longmate J, Scaringe WA, Sommer SS. Environ Mol Mutagen. 2004;43:110–120. doi: 10.1002/em.20004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thybaud V, Dean S, Nohmi T, de Boer J, Douglas GR, Glickman BW, Gorelick NJ, Heddle JA, Heflich RH, Lambert I, et al. Mutat Res. 2003;540:141–151. doi: 10.1016/j.mrgentox.2003.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Agresti A. Categorical Data Analysis. New York: Wiley; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Farabaugh PJ. Nature. 1978;274:765–769. doi: 10.1038/274765a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.de Boer JG, Glickman BW. Genetics. 1998;148:1441–1451. doi: 10.1093/genetics/148.4.1441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.