Abstract

Myelin-reactive T cells are considered to play an essential role in the pathogenesis of multiple sclerosis (MS), an autoimmune disease of the central nervous system. We have previously studied the effects of T cell vaccination (TCV), a procedure by which MS patients are immunized with attenuated autologous myelin basic protein (MBP)-reactive T cell clones. Because several myelin antigens are described as potential autoantigens for MS, T cell vaccines incorporating a broad panel of antimyelin reactivities may have therapeutic effects. Previous reports have shown an accumulation of activated T cells recognizing multiple myelin antigens in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of MS patients. We conducted a pilot clinical trial of TCV with activated CD4+ T cells derived from CSF in five MS patients (four RR, one CP) to study safety, feasibility and immune effects of TCV. CSF lymphocytes were cultured in the presence of rIL-2 and depleted for CD8 cells. After 5–8 weeks CSF T cell lines (TCL) were almost pure TCRαβ+CD4+ cells of the Th1/Th0 type. The TCL showed reactivity to MBP, MOG and/or PLP as tested by Elispot and had a restricted clonality. Three immunizations with irradiated CSF vaccines (10 million cells) were administered with an interval of 2 months. The vaccinations were tolerated well and no toxicity or adverse effects were reported. The data from this small open-label study cannot be used to support efficacy. However, all patients remained clinically stable or had reduced EDSS with no relapses during or after the treatment. Proliferative responses against the CSF vaccine were observed in 3/5 patients. Anti-ergotypic responses were observed in all patients. Anti-MBP/PLP/MOG reactivities remained low or were reduced in all patients. Based on these encouraging results, we recently initiated a double-blind placebo-controlled trial with 60 MS patients to study the effects of TCV with CSF-derived vaccines in early RR MS patients.

Keywords: activated CD4+ T cells, cerebrospinal fluid, multiple sclerosis, pilot clinical trial, T cell vaccination

INTRODUCTION

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic inflammatory disease of the central nervous system (CNS) white matter, characterized by focal areas of demyelination [1]. Although the exact mechanism of disease initiation remains elusive, it is postulated that CD4+ T cells play an essential role in the pathogenesis of MS by targeting components of myelin sheaths such as myelin basic protein (MBP), proteolipid protein (PLP) and myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) [2,3].

Based on the potential pathogenicity of myelin reactive T cells several immunotherapeutic strategies have been designed to specifically inactivate these T lymphocytes [4]. One possible therapeutic approach involves immunization with attenuated myelin-reactive T cells. This so-called ‘T cell vaccination’ (TCV) has been shown previously to prevent disease initiation and to induce remission in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), an animal model for MS, by enhancing the existing peripheral regulatory network [5]. The protective effects involve both an anti-idiotypic T cell response, recognizing T cell receptor (TCR) determinants [6] and an antiergotypic regulatory T cell response based on interactions with activation markers [7]. The successful results of T cell vaccination in animal studies led to human clinical trials conducted to evaluate the therapeutic effect of TCV as a treatment strategy for MS [8–10]. A pilot trial was performed in a small number of MS patients to assess safety of and immunological responses to T cell vaccination [9,11,12]. Patients were immunized three times with autologous irradiated MBP-reactive T cell clones. Subcutaneous inoculations of the vaccine cells were well-tolerated and caused no adverse effects. Clinical data suggested a moderate improvement in some relapsing-remitting (RR)-MS patients [11]. Furthermore, vaccinations induced an effective anticlonotypic T cell response in all patients, associated with a specific depletion of MBP-reactive T cells [9]. These results were confirmed in an extended phase I open label trial with 49 MS patients [13,14]. Further analysis of the antivaccine response revealed that CD8+ T cells display a direct cytolytic anti-idiotypic effect, whereas CD4+ T cells are the predominant cytokine producers. In addition, other cell populations are expanded upon stimulation with the vaccine clones including γδ T cells and NK cells, which may also play a role in the peripheral regulatory network [14]. Furthermore, it was shown that a significant anticlonotypic T cell response was still present several years after vaccination [15]. However, in five patients MBP-reactive T cells reappeared in the circulation and this coincided with clinical relapses in two of these patients [16]. Reappearing T cells belonged to a different clonal origin and were depleted successfully in subsequent rounds of vaccination [15,16]. In conclusion, these pilot studies indicated that T cell vaccination with attenuated autologous MBP-reactive T cell clones is safe and feasible, and that this experimental treatment induces a specific antivaccine response, thereby enhancing the peripheral immunoregulatory networks.

Increasing evidence indicates that T cells recognizing other myelin components may also contribute to the disease process in MS. Experiments in EAE and studies on human T cell reactivity demonstrated that PLP and MOG may play an important role as candidate myelin antigens in the autoimmune mediated demyelination [17–22]. Incorporating T cell populations specific for these autoantigens in the vaccines may improve the effectiveness of the current TCV protocol. However, technically it is almost impossible to generate T cell clones specific for three different myelin antigens with the current protocol design. Interestingly, it has been shown that a higher frequency of activated myelin-reactive T cells is present in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) compared to peripheral blood [23–27]. Moreover, the population of CSF lymphocytes reflects the repertoire of inflammatory cells infiltrating the parenchyma more effectively and may contain infiltrating pathogenic cells relevant to the disease process because of its proximity to the target organ in MS [28].

Based on these observations and a prior study to determine the optimal expansion conditions of CSF-derived activated T cells, a protocol was developed to expand activated CD4+ T lymphocytes from CSF of MS patients. We were able to grow these T cells to sufficient numbers for vaccination (107 T cells) after stimulation with low doses of recombinant human interleukin-2 in the presence of irradiated autologous feeder cells [25]. Using immunomagnetic beads, other mononuclear cell populations were depleted successfully from the CSF cell cultures. In this pilot trial of CSF-based T cell vaccination, five MS patients were immunized subcutaneously three times with 107 irradiated activated CD4+ T cells at 2-month intervals. We characterized the T cells used for vaccination and studied safety, feasibility and immune effects following immunization. T cell vaccines consisted predominantly of activated Th1/0 TCRαβ+ CD4+ T cells, showed reactivity towards at least two out of three myelin antigens tested and had a restricted clonality as determined by TCR analysis. The vaccinations were tolerated well and all patients remained clinically stable on EDSS without relapse during and at least 4 months after treatment. Another 6–12 months later, two patients worsened on EDSS (one RR-MS and one CP-MS), and in the RR-MS patient this was accompanied by a relapse. Both anti-idiotypic responses against the vaccine cells and antiergotypic responses were observed after vaccination in the majority of the patients. Myelin reactivities in the peripheral blood towards MBP, PLP and MOG remained low or were further reduced in all patients. In conclusion, these preliminary data illustrate that T cell vaccination with CSF-derived CD4+ activated T cells is feasible and safe and induces a specific antivaccine response.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

Five patients with clinically definite MS received three subcutaneous vaccinations containing 10 million CSF-derived activated CD4+ T cells at 2-month intervals. A lumbar puncture was performed at time 0, patients were immunized after months 2, 4 and 6 and followed-up until 10–15 months after the last vaccination. Four months after the last vaccination, a second CSF sample was obtained for postvaccination analysis. For each patient, MRI-scans were performed before the first and after the third vaccination. During the whole procedure, patients were monitored monthly for safety parameters and changes in clinical or immunological status. The clinical study was approved by the ethical committee of the Limburgs Universitair Centrum (Diepenbeek, Belgium).

Patients

Table 1 shows an overview of the patient characteristics. The five patients (four female/one male) participating in this study all had clinically definite MS: four of the relapsing-remitting (RR) type and one of the secondary progressive (CP) type. The mean age was 36·8 (range 24–51) years, mean disease duration at the time of study entry was 7·4 (range 1–28) years and baseline EDSS scores varied from 1·0 to 6·5. The four RR-MS patients showed a relapse rate from 1 to 3 during the last 2 years before entering the study. None of the patients used immunosuppressive or immunomodulatory drugs within 3 months before study entry. All participating patients signed a letter of informed consent.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics at study entry

| Subject | Sex | Age | Disease typea | Disease duration | EDSS | Relapse rateb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMH | F | 36 | RR | 3 | 2·5 | 3 |

| VEL | F | 24 | RR | 2 | 1·0 | 1 |

| FRW | M | 31 | RR | 3 | 3·5 | 2 |

| LIB | F | 51 | RR | 1 | 3·5 | 2 |

| JEL | F | 42 | SP | 28 | 6·5 | n.a. |

Disease type: RR: relapsing-remitting; SP: secondary progressive

number of relapses in a period of 2 years prior to study entry; EDSS: expanded disability status scale; n.a.: not applicable.

Cell culture media and antigens

Cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with L-glutamine, sodium pyruvate, non-essential amino acids and 10 mM HEPES buffer (Life Technologies, Paisley, Scotland, UK) and either 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS, Hyclone Europe, Erembodegem, Belgium) or 10% heat-inactivated autologous serum. Human MBP was purified from white matter of normal human brain according to the method of Deibler [29]. The synthetic myelin peptides MBP (84–102), MBP (143–168), PLP (41–58), PLP (184–199), PLP (190–209), MOG (1–22), MOG (34–56), MOG (64–86) and MOG (74–96) were synthesized and HPLC purified (>95% purity) by Severn Biotech Ltd (Worcester, UK) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Amino acid sequence of synthesized myelin peptides

| Myelin peptide | Amino acid sequence |

|---|---|

| MBP (84–102) | NPVVHFFKNIVTPRTPPPS |

| MBP (143–168) | GVDAQGTLSKIFKLGGRDSRSGSPMA |

| MOG (1–22) | GQFRVIGPRHPIRALVGDEVEL |

| MOG (34–56) | GMEVGWYRPPFSRVVHLYRNGKD |

| MOG (64–86) | EYRGRTELLKDAIGEGKVTLRIR |

| MOG (74–96) | DAIGEGKVTLRIRNVRFSDEGGF |

| PLP (41–58) | GTEKLIETYFSKNYQDYE |

| PLP (184–199) | QSIAFPSKTSASIGSL |

| PLP (190–209) | SKTSASIGSLCADARMYGVL |

Generation of CSF-derived activated CD4+ T cell vaccines

Fresh CSF-derived mononuclear cells were isolated after centrifugation of the cerebrospinal fluid obtained by lumbar puncture (10–15 ml). Cells were resuspended in autologous medium, counted and cultured for 10–12 days at cell densities of 2 × 104 cells/well, in the presence of 105 irradiated autologous peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) as feeder cells and low concentrations of recombinant human IL-2 (2 U/ml rhIL-2, Roche Diagnostics, Brussels, Belgium). In parallel, freshly isolated PBMC were plated out. Every 7–14 days, cell cultures were phenotypically characterized by flow cytometric analysis with a set of fluorochrome-conjugated mAb: anti-CD4/CD8, anti-CD3/CD16-56, anti-CD25/CD3, anti-TCRαβ/TCRγδ and antimouse IgG1/IgG2a as an isotype control (BD Biosciences). Lymphocyte subsets other than CD4+ T cells (CD8+ T cells, TCRγδ T cells or NK cells) representing> 15% of the total cell population were depleted using immunomagnetic beads (Dynal, Skoyen, Norway). Depletion efficiency (typically> 95%) was monitored by flow cytometric analysis. Cells were further expanded by repeated stimulation with autologous feeder cells and rhIL-2. At regular time-points, T cell cultures were analysed for their phenotype and, if necessary, depleted from non-CD4+ T cell subsets during the expansion period. One week prior to the first vaccination, T cells were activated with freshly isolated irradiated autologous feeder cells and rhIL-2. Ten million attenuated (6000 rad, Cs-source) autologous CSF-derived activated T cells were used for vaccination. The remaining cells were aliquoted and frozen for subsequent immunizations and used for detailed vaccine characterization as described below.

Analysis of cytokine profiles

To analyse the cytokine secretion profiles of CSF-derived vaccine cells, 2 × 104 cells were stimulated with phytohaemagglutinin (PHA, 2 µg/ml, Difco, Detroit, MI, USA) in the presence of 105 irradiated autologous PBMC or 105 irradiated autologous PBMC alone. After 72 h, cell supernatants were harvested and the cytokine production was measured using a sandwich ELISA based on commercially available monoclonal antibody pairs according to the manufacturer's instructions (Cytosets, Biosource Europe, Nivelles, Belgium). Optical densities were measured at 450 nm and 630 nm using an automated ELISA reader (ICN Biomedicals, Asse, Belgium) and sample concentrations were calculated using standard curves. Cells stimulated with PHA were analysed for production of IL-4, IL-6, IL-10, TNF-α and IFN-γ. Net cytokine secretion was calculated by subtracting background levels (cells without PHA) from the levels measured in the stimulated cultures.

T cell receptor (TCR) expression analysis

We determined the clonal heterogeneity of T cells of the three subsequent CSF-vaccines of PBMC isolated before the first and after the third vaccination and, if possible, of CSF-derived T cells obtained after the third vaccination. Cells were pelleted, washed twice in ice-cold PBS and immediately frozen at −70°C. Total RNA was extracted using the High Pure total RNA isolation kit (Roche Diagnostics, Brussels, Belgium) and reverse-transcribed into first-strand cDNA using oligo dT (Promega, Madison, WI, USA).

Semiquantitative TCR BV gene repertoire screening using PCR-ELISA

PCR-ELISA was performed as described previously [30]. Relative expression of TCR BV genes in the total TCR BV gene repertoire were presented as fractions of the total TCR BV gene expression using the following formula: % BVx = (OD450 (BVx) × 100)/Σ OD450 (BVn).

Overrepresented TCR BV genes were defined as exceeding an arbitrarily defined cut-off value based on the mean TCR BV gene expression levels in the blood of 10 healthy controls + 3 standard deviations (s.d.).

Clonal analysis: CDR3 sequencing

CDR3 region sequences were determined as described previously [31]. Briefly, cDNA of overrepresented TCR BV genes was amplified using the TCR BV region-specific and a TCR BC region-specific primer. PCR amplicons were ligated in the pCR2·1 cloning vector and transformed by heat shock in Escherichia coli cells following the manufacturer's instructions (TOPO TA Cloning Kit, Invitrogen, Leek, the Netherlands). Subsequently, plasmid DNA was isolated from 15 to 25 recombinant plasmids. After an additional round of amplification of the insert with TCR BV and TCRBC region specific primers, the amplicons were sequenced with a TCR BC region-specific primer using the Big Dye™ Terminator Cycle Sequencing Ready Reaction Kit (Applied Biosystems, Warrington, UK). Fluorescently labelled PCR amplicons were purified and DNA sequences were evaluated on an ABI Prism 310 Genetic Analyser (Applied Biosystems).

Clonal analysis: CDR3 spectratyping

CDR3 region spectrotype analysis was performed as described earlier [30,32]. CDR3 spectratype analysis provides information about the clonal composition of specific BV gene families. Polyclonal T cell populations show a Gaussian distribution profile with at least four peaks. A less heterogeneous profile with two to four peaks represents an oligoclonal T cell population, whereas a single peak in the CDR3 spectratype profile strongly suggests a monoclonal T cell population.

Frequency analysis of myelin-reactive T cells determined by ELISPOT

Myelin reactivity of CSF-derived cultured T cells was tested in an IFN-γ ELISPOT assay as described earlier (Mabtech, Sweden) [33]. We tested triplicate wells of 2 × 104 vaccine T cells cultured in the presence of 105 irradiated autologous PBMC (as antigen presenting cells) and antigen. Reactivity was tested to a panel of synthetic MBP, PLP or MOG peptides (10 µg/ml each, Table 1), control stimuli (PHA or anti-CD3, 2 µg/ml) or no antigen added. Spots were counted using a dissection microscope. The number of cytokine-secreting cells was calculated by subtracting the number of spots in control wells (without antigen) from the number of spots obtained in the presence of the stimulating agent.

In parallel, an IL-4 ELISPOT assay was performed using the anti-IL-4 antibody pair from MabTech. Interassay variability and reproducibility of the ELISPOT assays were as reported previously [33].

Frequency analysis of myelin-reactive T cells determined by limiting dilution analysis

Before the first and after the third vaccination, PBMC were isolated from heparinized blood by Histopaque density centrifugation (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA), washed extensively, counted and suspended in autologous medium. Subsequently, cells were plated at 105 cells per well in U-bottom 96-well plates (Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark) in the presence of MBP (40 µg/ml, 60 wells), a mixture of the three PLP peptides (10 µg/ml each, 30 wells) or a mixture of the three MOG peptides (10 µg/ml each, 30 wells). In parallel 60 wells of 4 × 104 PBMC per well were cultured with Tetanus toxoid (TT, 2·5 Lf/ml, RIVM, Bilthoven, the Netherlands). After 7 days, cultures were restimulated with 105 irradiated autologous PBMC pulsed with the corresponding antigen and supplemented with 2 U/ml rhIL-2. At day 14, each TCL was tested for antigen specificity. Briefly, 50% of the cells in a cultured well were split into four wells and restimulated in duplicate with 105 irradiated antigen-pulsed or non-pulsed autologous PBMC. After 3 days, proliferation capacities were measured using a classical [3H]-thymidine incorporation assay. During the last 16 h of culture, cells were pulsed with 1 µCi [3H]-thymidine (Amersham, Buckinghamshire, UK) and harvested with an automated cell harvester (Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden). Incorporated radioactivity was measured with a Beta-plate liquid scintillation counter (Wallac, Turku, Finland). The criteria for a positive antigen-specific T cell line were set at a stimulation index (SI) > 3 and a minimum value of 1500 counts per minute (cpm).

Proliferative response to vaccine cells and PHA-stimulated T cell blasts

At various time-points before, during and after the immunization program, freshly isolated PBMC (5 × 104 cells/well) were cocultured in triplicate with 5 × 104 irradiated stimulator cells for 72 h, as described previously [9]. The immunizing vaccine T cells or PHA-activated T cell blasts were used as stimulators. To prepare activated T cell blasts, PBMC were cultured in the presence of 1 µg/ml PHA and 5 U/ml rhIL-2 for 7 days and washed extensively. As control, PBMC and irradiated stimulator T cells were cultured alone. Cell proliferation was measured in a classical proliferation assay as described above, and stimulation indices (SI) calculated as follows: (cpm of PBMC co-cultured with irradiated stimulator T cells)/(cpm of PBMC cultured alone) + (cpm of irradiated stimulator T cells alone).

Monitoring safety and clinical status variables

During the entire study period, all patients were monitored for safety using standard toxicity assays and were observed for adverse effects following the immunization protocol. To determine expanded disability status score (EDSS) and relapse rate, neurological examinations were performed. A clinical relapse was defined as the appearance, or reappearance, of one or more neurological abnormalities persisting for at least 48 h [34]. Patients were asked to report changes in symptoms and/or the appearance of new symptoms. Clinical relapses were confirmed by the evaluating neurologist at the next scheduled visit. Brain MRI were obtained before the first vaccination and after the third vaccination using a 1·5 Tesla instrument (Magneton Symphony, Siemens, Erlangen, Germany). Using two interleaved series of turbo spin-echo dual echo sequences, proton density (Pd, TR: 2560 ms, TE: 11 ms) and T2-weighted (T2w, TR: 600 ms, TE: 12 ms) images were obtained. These sequences are followed by two interleaved series of T1-weighted spin-echo sequences (T1w, TR: 600 ms, TE: 12 ms) after administration of Gadolinium (Gd). All sequences were acquired with a slice thickness of 3 mm, an interslice gap of 3 mm, a field of view of 250 mm and a 190/256 matrix for Pd and T2w images or a 192/256 matrix for T1w images. The total number of T1w and T2w lesions and the number of Gd enhanced T1w lesions were counted. T1w Gd-enhanced lesions and new or enlarging T2w lesions were considered to be active lesions, as described [22]. Lesions that appeared on T2w scans and were also Gd-enhanced on T1w images were counted only once as an active lesion.

RESULTS

Vaccine preparation

For four of five MS patients, we were able to expand CSF-derived mononuclear cells to sufficient numbers to perform three immunizations. Most patients received 107 vaccine cells in each of the three immunizations. Due to culturing difficulties, the first vaccines of patient FRW and JEL contained 2–3 million cells only. For one patient (VEL), cells from the CSF could not be cultured. Instead, we performed three vaccinations using rhIL-2 expanded mononuclear cells from peripheral blood.

Vaccine characterization

Phenotypic analysis

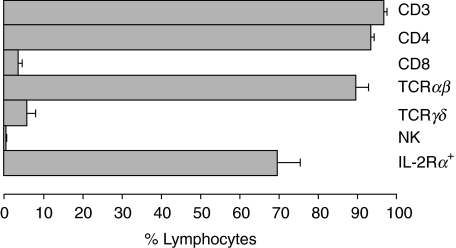

Flow-cytometric analysis demonstrated that vaccines were composed of TCRαβ+ CD4+ T cells (93·5 ± 0·9%) with a variable expression of the IL-2 receptor α chain (CD25, 69·7 ± 5·7%). Little or no CD8+ T cells (3·5 ± 1·1%), γδ+ T cells (5·7 ± 2·3%) or natural killer cells (CD16+ 56 + ; 0·16 ± 0·08%) were present in the vaccines (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Mean phenotypic expression profiles of T cell vaccines. Bars represent the mean percentages of cellular subsets. Standard errors of the mean (s.e.m.) are shown in horizontal lines. Mean percentages of total T cells (CD3), T helper cells (CD4), cytotoxic T cells (CD8), TCRαβ+ T cells (TCRαβ), γδ T cells (TCRγδ), natural killer cells (NK, CD16/56) and activated T cells (IL-2 receptor α chain (CD25)+) are shown for the three vaccines of the five MS patients. □, 10 pg/ml;  , 11–100 pg/ml;

, 11–100 pg/ml;  , 101–500 pg/ml;

, 101–500 pg/ml;  , 501–1000 pg/ml;

, 501–1000 pg/ml;  , >1000 pg/ml.

, >1000 pg/ml.

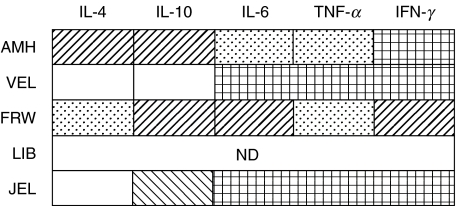

Cytokine profile

Next, the cytokine secretion profiles of T cell lines used for the first vaccination were analysed after in vitro stimulation with phytohaemagglutinin (PHA) and feeders. TNF-α, IFN-γ and IL-6, produced by Th1 cells, and IL-4 and IL-10, produced by Th2 cells, were measured by ELISA in the supernatants of the cell cultures. In the four vaccines tested, high levels of TNF-α, IFN-γ and IL-6 were measured (Fig. 2). CSF-derived T cells from two patients (AMH and FRW) also produced moderate amounts of IL-4 and IL-10, and were subtyped as Th0-type cells (Fig. 2). In contrast, Th2-specific cytokines were not present in the cell culture supernatants of the two other patients (VEL and JEL). These T cell vaccines consisted predominantly of Th1-like cells.

Fig. 2.

Cytokine production of T cell vaccines. T cell vaccines used for the first vaccination were stimulated with PHA. After 3 days, cell supernatants were harvested and cytokine levels were measured by ELISA. Net cytokine production (in pg/ml) of IL-4, IL-10, IL-6, TNF-α and IFN-γ was calculated by subtracting background levels (without PHA) from the cytokine levels determined in the PHA-stimulated cultures. ND: not determined. □, <10 pg/ml;  , 11–100 pg/ml;

, 11–100 pg/ml;  , 101–500 pg/ml;

, 101–500 pg/ml;  , 501–1000 pg/ml;

, 501–1000 pg/ml;  , >1000 pg/ml.

, >1000 pg/ml.

Myelin reactivity

Myelin specificity of the vaccine cells was tested at the time of the first vaccination. The recognition pattern of immunodominant peptides of MBP, PLP and MOG was analysed by IFN-γ and IL-4 ELISPOT using 2 × 104 vaccine cells in the presence of 105 irradiated autologous PBMC as antigen presenting cells. No IL-4-secreting cells were detected after stimulation with the myelin peptides, although a high IL-4 production was found against the control stimuli PHA and anti-CD3. IFN-γ-secreting vaccine cells displayed a heterogeneous reactivity towards different peptides of the three myelin antigens tested (Table 3). In three of four cell cultures we found relatively high reactivity towards MOG. All four T cell cultures tested recognized one or more PLP peptide, but to a lesser extent. Although MBP-specific T cells were demonstrated in only two patient vaccines, we cannot exclude the possibility that T cells recognizing other MBP epitopes are present, as only two immunodominant peptides of the MBP protein were tested. Furthermore, pilot experiments using low numbers of pure MBP- or MOG-specific Th1 cell clones demonstrated that the number of spots detected does not always correspond to the number of myelin-reactive T cells added (data not shown). Indeed, theoretically every myelin-specific T cell should produce IFN-γ upon stimulation with the peptide it is recognizing. However, counting the number of spots showed that only 1/10 of the cells derived from the myelin-specific T cell clone secreted IFN-γ after stimulation with the corresponding myelin peptide or a control stimulus (anti-CD3) (data not shown).

Table 3.

Myelin reactivity of T cell vaccines

| Antigen reactivity | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient | MBPa | PLPa | MOGa | TT |

| AMH | 8 | 5 | 17 | 4 |

| VEL | 9 | 8 | 25 | 2 |

| FRW | NI | |||

| LIB | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| JEL | 0 | 3 | 17 | 0 |

T cell vaccines used for the first vaccination were tested for myelin reactivity by ELISPOT. 2×104 vaccine cells in the presence of 105 antigen-presenting cells were incubated with a mixture of different peptides available of MBP (84–102 and 143–168), PLP (41–58, 84–99 and 196–209) and MOG (1–22, 34–56, 64–86 and 74–96). The sum of the positive spots is shown for each myelin antigen peptide mixture. TT: Tetanus toxoid, control antigen; NI: not identified; for patient FRW, the ELISPOT assay failed twice.

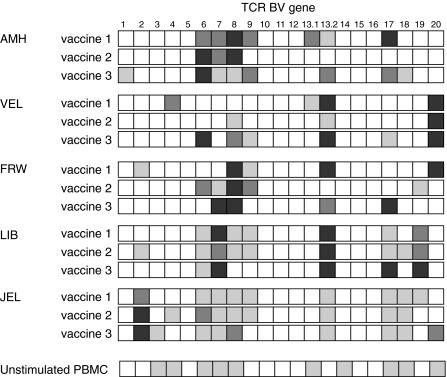

Clonal composition

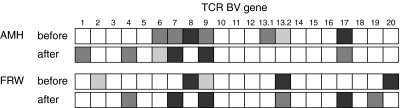

To study the clonal composition of the three subsequent vaccines for each patient, the TCR BV gene expression profiles were analysed by a semiquantitative PCR-ELISA assay. The TCR BV gene expression in the vaccine cells is restricted and only a limited number of BV genes are overexpressed (Fig. 3). The three vaccines from one patient had a stable BV gene expression profile. For example, in patient LIB, BV 7 and BV 13·2 are overrepresented in all three vaccines. In addition, an increased expression of BV 6, BV 17 and BV 19 was observed in the three cell populations. Despite the limited number of overexpressed TCR BV genes in all patient cultures, overrepresented BV genes definitely varied among different patients. In general, the BV gene expression pattern in the vaccines was different among patients (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

TCR BV gene expression profiles in the T cell vaccines of five MS patients. T cell vaccines were submitted to semiquantitative PCR-ELISA analysis to determine the TCR BV gene expression repertoire. As a comparison to illustrate the skewed BV gene usage of the cultured vaccine T cells, the mean TCR BV gene expression profile of unstimulated PBMC from 10 healthy controls is shown. The expression of each individual TCR BV gene (A450(BVx)) is presented as a percentage of the total BV gene expression (Σ A450(BVn)). □, <5%  , 5–10%;

, 5–10%;  , 10–15%; ▪, <15%.

, 10–15%; ▪, <15%.

CDR3 spectratype analysis provides information about the clonal composition of specific BV gene families. Identical fragment lengths of PCR amplified CDR3 regions, which are depicted as peaks in the profile, suggest strongly that identical T cell clones are present in different samples. Furthermore, the height of the peaks corresponds to the frequency of a specific clonotype within a given BV gene family. In general, the majority of the analysed TCR BV gene families in the T cell vaccines showed a restricted clonal origin as demonstrated by predominantly mono- or oligoclonal CDR3 spectratype profiles (Fig. 4). Furthermore, comparison of the different clonotypes of the three vaccine samples within a given BV gene family also indicates that identical T cell clones are present in different samples, although the frequency (determined by peak height) may vary at different time-points (Fig. 4). For example, CDR3 fragment length analysis of the TCR BV 6 gene family in patient AMH shows an oligoclonal profile for all three vaccines, as illustrated in Fig. 4a. In vaccine 1, three different peaks are present and the dominant clonotype also persists in vaccine 2. The oligoclonal T cell population of vaccine 3 is represented by three different clonotypes but the frequency of the dominant clonotype from vaccine 1 and 2 is much lower in this sample. Interestingly, in the unstimulated PBMC a restricted oligoclonal profile, with the same dominant clonotype was also observed (Fig. 4a). Figure 4b illustrates the persistence of a given clonotype in the BV 7 T cell populations of the three vaccines of patient FRW. Although at time-point 2 and 3 a monoclonal CDR3 spectratype profile is observed, this clonotype is also present in vaccine 1 but at a lower frequency. Furthermore, the unstimulated PBMC were polyclonal with an increased frequency of one peak. The CDR3 fragment length of this band corresponds to the dominant peak in the CSF-derived vaccine samples. This may indicate an increased expression level in the peripheral blood after in vivo activation and subsequent clonal expansion of this specific clonotype (Fig. 4b).

Fig. 4.

CDR3 fragment length screening of two selected TCR BV genes in the CSF-derived T cell vaccines from two MS patients. The clonal composition of two TCR BV gene families in the vaccine cultures of two different MS patients (a: patient AMH BV gene 6 and b: patient FRW BV gene 7) was determined after nested PCR amplification with a fluorescently labelled TCR BC region-specific primer of BV gene family amplicons. CDR3 fragment lengths were calculated using the Genescan-1000 ROX size standard and the 672 Genescan Software. Peaks with an identical CDR3 length in different samples are marked with a symbol (⋆, ♦ and ○).

In conclusion, TCR BV gene expression profiles and subsequent CDR3 region analysis of the three vaccines used for immunization showed a restricted but stable heterogeneity with different overrepresented BV genes between different patients.

CDR3 sequence analysis of overrepresented BV genes in patient AMH

For one patient (AMH), we also determined the clonal composition of different BV gene families in the three vaccine samples using CDR3 sequence analysis. To this end, the PCR products were cloned in a plasmid vector and 15–25 randomly selected recombinant clones were sequenced. Table 4 provides an overview of the CDR3 sequences of three BV gene families obtained in the three vaccine samples of patient AMH.

Table 4.

CDR3 sequence analysis of three TCR BV gene families in the vaccines of patient AMH

| Amino acid sequence | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TCR BV gene | Sample | Freqa | BVb | BnDnb | BJb | BCb |

| BV 6 | Vaccine 1 | 08/20 | YLCASS | VRGD | QPQHFGDGTRLSIL | EDLNK |

| 05/20 | YLCASSL | YGPLAGVG | EQFFGPGTRLTVL | EDLKN | ||

| 03/20 | YRCAS | RPGGG | GYTFGSGTRLTVV | EDLNK | ||

| 03/20 | YLCASS | DPGH | YGYTFGSGTRLTVV | EDLNK | ||

| 01/20 | YLCASS | VRGD | QPQHFGDGTRLSIL | EDLNK | ||

| Vaccine 2 | 20/22 | YLCASS | VRGD | QPQHFGDGTRLSIL | EDLNK | |

| 02/22 | YLCASSL | YGPLAGVG | EQFFGPGTRLTVL | EDLKN | ||

| Vaccine 3 | 24/24 | YLCASS | VRGD | QPQHFGDGTRLSIL | EDLNK | |

| BV 13·2 | Vaccine 1 | 06/20 | YFCAS | RDPPT | YNEQFFGPGTRLTVL | ELDKN |

| 03/20 | YFCASS | PFAGR | TEAFFGQGTRLTVV | EDLNK | ||

| 03/20 | YFCASSY | RGTLG | NEQFFGPGTRLTVL | EDLKN | ||

| 02/20 | YFCAS | RSPT | NTEAFFGQGTRLTVV | EDLNK | ||

| 01/20 | YFCASSY | SGTA | NYGYTFGSGTRLTVV | EDLNK | ||

| 01/20 | YFCAS | RNRGF | SYNEQFFGPGTRLTVL | EDLKN | ||

| 01/20 | YFCASSY | KGSG | TEAFFGQGTRLTVV | EDLNK | ||

| 01/20 | YFCAS | RLQGN | SNQPQHFGDGTRLSIL | EDLNK | ||

| 01/20 | YFCAS | GLQGN | SNQPQHFGDGTRLSIL | EDLNK | ||

| 01/20 | YFCAS | THQEYG | NQPQHFGDGTRLSIL | EDLNK | ||

| Vaccine 2 | 07/22 | YFCAS | RNRGF | SYNEQFFGPGTRLTVL | EDLKN | |

| 06/22 | YFCASSY | KGSG | TEAFFGQGTRLTVV | EDLNK | ||

| 04/22 | YFCAS | RDPPT | YNEQFFGPGTRLTVL | ELDKN | ||

| 03/22 | YFCASSY | RGTLG | NEQFFGPGTRLTVL | EDLKN | ||

| 01/22 | YFCASS | PFAGR | TEAFFGQGTRLTVV | EDLNK | ||

| 01/22 | YFCASSY | SGRTYD | EQFFGPGTRLTVL | EDLKN | ||

| Vaccine 3 | 10/21 | YFCASSY | KGSG | TEAFFGQGTRLTVV | EDLNK | |

| 09/21 | YFCASSY | SGTA | NYGYTFGSGTRLTVV | EDLNK | ||

| 02/21 | YFCAS | RNRGF | SYNEQFFGPGTRLTVL | EDLKN | ||

| BV 17 | Vaccine 1 | 21/24 | YLCASSI | RMD | TEAFFGQGTRLTVV | EDLNK |

| 01/24 | YLCASS | GHTGDN | NSPLHFGNGTRLTVT | EDLNK | ||

| 01/24 | YLCASSI | VPG | SGANVLTFGAGSRLTVL | EDLKN | ||

| 01/24 | YLCASSI | PRGGSG | YGYTFGSGTRLTVV | EDLNK | ||

| Vaccine 2 | 18/20 | YLCASSI | RMD | TEAFFGQGTRLTVV | EDLNK | |

| 02/20 | YLCASSI | VPG | SGANVLTFGAGSRLTVL | EDLKN | ||

| Vaccine 3 | 05/09 | YLCASSI | RMD | TEAFFGQGTRLTVV | EDLNK | |

| 03/09 | YLCASSI | GG | NEQFFGPGTRLTVL | EDLKN | ||

| 01/09 | YLCASSI | VPG | SGANVLTFGAGSRLTVL | EDLKN | ||

Freq: frequency; number of plasmids with a particular CDR3 amino acid sequence as a fraction of the total number of plasmids sequenced for a given TCR BV gene in a specific sample

BV: variable region of the TCR beta chain; BnDn: diversity region of the TCR beta chain; BJ: junctional region of the TCR beta chain; BC: constant region of the TCR beta chain. Identical CDR3 sequences within a specific TCR BV gene family are presented in italic and/or bold type.

These results demonstrate that TCR BV gene families consisted of a limited number of different T cell clones and that identical clonotypes are persistent in the three vaccines, although the frequency may vary. This finding is consistent with the previously described data on CDR3 fragment length analysis. For BV6, CDR3 sequence ‘VRGD’ represents the dominant clone in vaccine 1, although several other clonotypes are present. In vaccines 2 and 3, this T cell clone accounts for>90% (20/22) and even 100% (24/24) of the randomly selected TCR BV 6 gene products. Within the BV 17 gene family, high frequencies of the dominant T cell clone with CDR3 sequence ‘RMD’ are found in vaccine 1 (21/24), vaccine 2 (18/20) and vaccine 3 (5/9). Although the clonal composition of the less expressed BV 13·2 gene family is more heterogeneous, similar CDR3 sequences are found in the three different samples (Table 4).

In conclusion, CDR3 sequence analysis of T cell clones present in a given TCR BV gene family demonstrated a stable and restricted clonal composition of vaccine T cell populations in the three vaccines of patient AMH.

Immunological follow-up

Frequency of myelin-reactive T cells

To study the effect of CSF-based T cell vaccination on circulating myelin-reactive T cells in the peripheral blood, we determined the frequency of antimyelin T cells before and after vaccination by limiting dilution analysis. PMBC were plated out in the presence of native MBP, PLP-peptide mix or MOG-peptide mix. Tetanus toxoid was used as a control antigen. After 14 days, using a classical proliferation assay, the number of antigen-specific T cell lines was determined. Frequencies of antimyelin T cells before and after vaccination are shown in Table 5. In two patients (FRW and JEL), the frequency of myelin-specific T cells was low before vaccination and remained stable after vaccination. However, in three of five patients, T cell lines reactive towards the three myelin antigens tested are present in the peripheral blood before vaccination. Interestingly, after vaccination, no myelin-reactive T cells could be found in one patient (LIB). Furthermore, in patients AMH and VEL, who had relatively high frequencies of anti-MBP, anti-PLP and anti-MOG T cells before vaccination, a significant decline of circulating myelin-specific T cells was observed after vaccination (Table 5). In contrast, no significant changes in the T cell frequency to the control antigen Tetanus toxoid was observed. In conclusion, these data indicate that following T cell vaccination antimyelin reactivity in the peripheral blood remained low or was further reduced in all patients.

Table 5.

Frequency of myelin-reactive T cells before and after vaccination

| Number of antigen-specific T cell linesa | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient | Antigen | before TCVb | after TCVb |

| AMH | MBP (60 wells) | 5 | 1 |

| PLP (30 wells) | 2 | 0 | |

| MOG (30 wells) | 14 | 0 | |

| Tetanus toxoid (30 wells) | 4 | 7 | |

| VEL | MBP (60 wells) | 16 | 0 |

| PLP (30 wells) | 3 | 2 | |

| MOG (30 wells) | 7 | 0 | |

| Tetanus toxoid (30 wells) | 18 | 17 | |

| FRW | MBP (60 wells) | 2 | 3 |

| PLP (30 wells) | 0 | 0 | |

| MOG (30 wells) | 1 | 1 | |

| Tetanus toxoid (30 wells) | NT | NT | |

| LIB | MBP (60 wells) | 3 | 0 |

| PLP (30 wells) | 1 | 0 | |

| MOG (30 wells) | 1 | 0 | |

| Tetanus toxoid (30 wells) | 0 | 0 | |

| JEL | MBP (60 wells) | 1 | 0 |

| PLP (30 wells) | 0 | 1 | |

| MOG (30 wells) | 0 | 2 | |

| Tetanus toxoid (30 wells) | 0 | 0 | |

Frequency of myelin-specific T cells was determined by limiting dilution analysis. Reactivity towards MBP, PLP (peptide mix) and MOG (peptide mix) was tested. In addition, a control antigen (Tetanus toxoid) was incorporated to provide information about the fluctuations in the immune response in general.

Frequency analysis was performed with freshly isolated PBMC shortly before the first vaccination and 4 months after the third vaccination. TCV: T cell vaccination; NT: not tested.

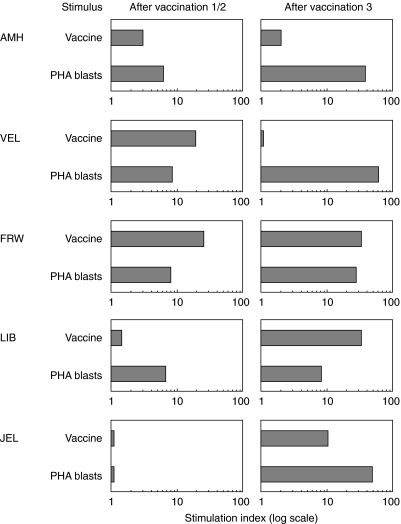

Proliferative antivaccine response

To study the cellular immune response induced by T cell vaccination, PBMC of vaccinated patients were stimulated with irradiated vaccine cells or irradiated autologous PHA-stimulated T cell blasts (PHA blasts). The proliferative responses were evaluated at day 4 after stimulation using a classical [3H]-thymidine assay. Figure 5 summarizes the proliferative responses, induced by T cell vaccines or PHA blasts for the five MS patients 1 month after the first or second and third vaccinations. Significant proliferative responses (SI > 3) towards the vaccine cells were observed in four of five patients. For two patients (LIB and JEL), the proliferative response was more pronounced after the third vaccination (SI of 10 and 32, respectively). Patient VEL showed the highest antivaccine response after the second vaccination, and high stimulation indices were calculated after each vaccination for patient FRW. In addition, strong proliferative responses were induced after stimulation with autologous PHA T cell blasts in all five patients. This antiergotypic response was more pronounced after the third vaccination (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Proliferative response to T cell vaccines and autologous PHA-stimulated T cell blasts after vaccination. Freshly isolated PBMC from vaccinated patients were stimulated with irradiated vaccine cells or irradiated autologous PHA-stimulated T cell blasts 1 month after each vaccination. After 4 days, cells were harvested and proliferative responses were evaluated in a classical [3H]-thymidine incorporation assay. Based on the incorporated radioactivity, stimulation indices were calculated.

In conclusion, these data demonstrate that immunization with activated T cells induced a specific anti-idiotypic response (towards the vaccine T cells) in the majority of the patients. Furthermore, antiergotypic proliferative responses were observed in all patients, predominantly after the third vaccination.

Comparison of cultured CSF cells before and after vaccination

IL-2 expanded CSF cultures were compared before and after vaccination. Cell numbers after lumbar puncture (10–15 ml) varied significantly between patients (Table 6), both before (range: 5225–157 000 cells) and after vaccination (range 11 250–105 000 cells) and comparison of mean cell numbers showed a slight decrease of CSF cells after vaccination (before: 59 910 ± 28 708; after: 44 940 ± 16 910). Before vaccination, we were able to grow CSF-derived cells from four of five MS patients, and after depletion of CD8+ T cells and γδ cells, expanded CSF cultures consisted predominantly of CD4+ TCRαβ+ T cells after approximately 8 weeks of culture (Table 6). Remarkably, although similar cell numbers were obtained by lumbar puncture after the third vaccination, we could not grow CSF-derived T cells in two of five patients (LIB/JEL). Furthermore, CD8+ and γδ T cell populations were more persistent and could not always be depleted efficiently as is demonstrated by the phenotype expression profiles after approximately 8 weeks of culture (Table 6).

Table 6.

CSF cellularity before and after vaccination

| Phenotypec | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient | Cell numbera | Expansionb | CD4+ | CD8+ | γδ+ |

| AMH | |||||

| ″before | 40 000 | + | 95 | 5 | 21 |

| ″after | 23 900 | + | 9 | 35 | 62 |

| VEL | |||||

| ″before | 157 000 | – | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| ″after | 58 400 | + | 9 | 39 | 88 |

| FRW | |||||

| ″before | 90 000 | + | 90 | 8 | 12 |

| ″after | 105 000 | + | 80 | 1 | 19 |

| LIB | |||||

| ″before | 6 925 | + | 90 | 8 | 1 |

| ″after | 11 250 | – | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| JEL | |||||

| ″before | 5 625 | + | 95 | 0 | 2 |

| ″after | 26 150 | – | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

Cell number counted after lumbar puncture (10–15 ml) before expansion

expansion of CSF-derived cells using low doses of rhIL-2 was successful for four of five MS patients before vaccination, and for three of five MS patients after vaccination

phenotype of cultured CSF-derived cells as determined after 8 weeks of expansion and depletion of non-CD4+ T cell populations using immunomagnetic beads. In the CSF cultures after vaccination, large populations of CD8+ and/or γδ cells could not always be successfully depleted; n.d.: not determined.

For two patients, AMH and FRW, we compared the TCR BV gene repertoire of cultured CSF-derived CD4+ T cells before and after vaccination (Fig. 6). In these patients, differences in TCR BV gene expression profiles were seen at the two time-points. Some TCR BV gene families were preferentially expressed only before or after vaccination (AMH BV 1, 4, 8 and 13·1; FRW BV 4, 7, 8, 17, 19 and 20) whereas for other T cell populations fluctuations in the TCR BV gene expression were observed. In addition, the clonal composition of four TCR BV gene families were analysed for patient AMH in CSF cultures and unstimulated PBMC before and after vaccination (Table 7). Although for both the TCR BV 6 and 13·2 gene family a reduced expression was observed in the cultured CSF (Fig. 6), the clonal composition of the CSF remained rather stable. For BV 6, the dominant clone ‘VRGD’ persisted in the CSF after treatment and was even more frequent in peripheral blood (VRGD, 16/17). A new dominant clonotype was found in CSF at the second time-point (IPAGGA, 6/19), whereas another clone was no longer detectable after vaccination (YGPLAGVG). For BV 13·2, the dominant clone ‘KGSG’ after vaccination (12/21), was also part of the more heterogeneous T cell population at the first time-point (KGSG, 1/20) and could also be detected in the blood at both time-points (before: 3/18; after: 6/21). The most predominant clone in the CSF before vaccination (RDPPT, 6/20) persisted in the CSF after treatment (RDPPT, 6/21). Although the dominant clone from the blood (SGTA, 15/18) was found with a lower frequency after vaccination (SGTA, 14/21), no increased frequency of this T cell clone was found in the CSF afterwards (SGTA, 1/21). A decreased expression of BV 17 was demonstrated by PCR-ELISA (Fig. 6). The dominant clone before vaccination for this BV gene family (RMD, 21/24) was after treatment only present in the CSF (RMD, 1/17) and in the blood (RMD, 1/26) at a very low frequency. However, although the dominant clone in the blood (GG, 13/16) was detected at lower frequency after vaccination (GG, 13/26), this clone was one of the two new and most abundant clonotypes in the CSF after vaccination (GG, 5/17; LEYRGQ, 6/17). Similar observations were reported for the TCR BV 9 family. The overrepresented T cell clone before vaccination (RTNN, 19/22), was found at lower frequency in the CSF cultures after vaccination (RTNN, 4/21). Furthermore, the dominant clone from the unstimulated PBMC before vaccination (PATLA, 8/19) persisted in the blood after vaccination and was also found at high frequency in the cultured CSF at the second time-point (PATLA, 8/21). This might indicate that some T cells migrated from the periphery to the CNS.

Fig. 6.

TCR BV gene expression profiles of cultured CSF-derived T cells before the first and after the third vaccination. CSF T cells obtained before the first and after the third vaccination by lumbar puncture were cultured for 8 weeks and depleted from non-CD4+ T cells prior to PCR-ELISA analysis. The expression of each individual TCR BV gene (A450(BVx)) is presented as a percentage of the total BV gene expression (Σ A450(BVn)). □, <5%;  , 5–10%;

, 5–10%;  , 10–15%; ▪, >15%.

, 10–15%; ▪, >15%.

Table 7.

CDR3 sequence analysis of four TCR BV gene families in cultured CSF T cells and unstimulated mononuclear cells from the blood before and after vaccination for patient AMH

| Evolutionc | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TCR BV gene | Sample | Amino acid sequencea | Frequencyb | before | after |

| BV 6 | CSF | VRGD | 8/20 | 8/19 | = |

| YPLAGVG | 5/20 | 0/20 | ↓ | ||

| IPPAGA | 0/20 | 6/19 | ↑ | ||

| PBMC | VRGD | 11/20 | 16/17 | ↑ | |

| YPLAGVG | 0/20 | 1/17 | = | ||

| VGEQ | 7/20 | 0/17 | ↓ | ||

| BV 9 | CSF | RTNN | 19/22 | 4/21 | ↓ |

| PATLA | 0/22 | 8/21 | ↑ | ||

| PBMC | RTNN | 0/19 | 1/21 | = | |

| PATLA | 8/19 | 14/21 | ↑ | ||

| BV 13·2 | CSF | RDPPT | 6/20 | 6/21 | = |

| KGSG | 1/20 | 12/21 | ↑ | ||

| SGTA | 1/20 | 1/21 | = | ||

| PBMC | KGSG | 3/18 | 6/21 | ↑ | |

| SGTA | 15/18 | 14/21 | ↓ | ||

| BV 17 | CSF | RMD | 21/24 | 1/17 | ↓ |

| GG | 0/24 | 5/17 | ↑ | ||

| LEYRGQ | 0/24 | 6/17 | ↑ | ||

| PBMC | RMD | 1/16 | 1/26 | ↓ | |

| GG | 13/16 | 13/26 | ↓ | ||

Amino acid sequence of the hypervariable diversity region of the TCR beta chain (BnDn) from dominant T cell clones within a specific BV gene family

the frequency is the number of plasmids with a particular CDR3 amino acid sequence as a fraction of the total number of plasmids sequenced for a given TCR BV gene in a specific sample;

evolution: comparison between frequency of a given T cell clone before and after vaccination: increased (↑), decreased (↓) or similar (=). BV: variable region of the β chain of the T cell receptor; CSF: cerebrospinal fluid; PBMC: peripheral blood mononuclear cells. CSF T cells cultured for about 8 weeks and depleted from non-CD4+ T cells were obtained before the first and after the third vaccination.

In conclusion, although no clear differences in the number of cells obtained after lumbar puncture could be found before and after vaccination, we were not able to isolate CD4+ T cells in four of five MS patients after vaccination because of large percentages of non-CD4+ T cell populations or poor expansion after IL-2 culturing. Furthermore, we found fluctuations in the TCR BV gene expression profiles and characterization of clonotypes in four BV gene families showed that some clones persisted after vaccination, others were found at significantly lower frequency and some T cells migrated from the peripheral blood into the CSF. Although this analysis allows to follow individual T cell clonotypes in CSF and blood before and after vaccination, it does not provide any information about a pathogenic or regulatory role of these T cells.

Safety and clinical parameters

Vaccinations were well tolerated and no toxicity or adverse effects were reported following administration of vaccine T cells. The data from this small open-label study cannot be used to support clinical efficacy. However, the patients were monitored for changes in clinical status variables at several time-points before, during and after vaccination (Table 8). As demonstrated by EDSS scores, patients remained clinically stable during and at least 4 months after treatment. After a longer period of 10–15 months after the last vaccination, one patient (FRW) showed a remarkable improvement of 2·0 points on the EDSS scale after treatment, whereas in two patients the EDSS score worsened. The remaining two patients were stable for the entire follow-up period. In addition, a reduced relapse rate was observed in all RR-MS patients. The mean relapse rate was 2·0 ± 0·4 during a period of 2 years prior to TCV and 0·3 ± 0·3 in a period of 14–20 months after the first vaccination. MRI scans were obtained before the first and after the third vaccination. We observed active lesions in three of five MS patients after the last vaccination (2–8 months) but thus far, this observation did not result in a clinical exacerbation. For the two remaining patients, no active lesions on MRI were detected at both time-points.

Table 8.

Overview of the clinical data

| EDSS scorea | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| after TCV | Relapse rateb | Active lesionsc | |||||

| Patient | before TCV | 4 m | 10–15 m | before TCV | after TCV | before TCV | after TCV |

| AMH | 2·5 | 2·5 | 4·5 | 3 | 1 | – | – |

| VEL | 1·0 | 1·0 | 1·0 | 1 | 0 | + | + |

| FRW | 3·5 | 2·0 | 1·5 | 2 | 0 | – | + |

| LIB | 3·5 | 3·5 | 3·5 | 2 | 0 | + | + |

| JEL | 6·5 | 6·5 | 7·5 | n.a. | n.a. | – | – |

EDSS scores as determined at study entry (before TCV), 4 months after the third vaccination (4 m) and 10–15 months after the third vaccination (10–15 m)

relapse rates were calculated for a period of 2 years prior to TCV treatment (before TCV) and calculated for a period of 14–20 months beginning at the date of the first vaccination (after TCV)

the presence of active MRI lesions was determined by MRI at one time-point before vaccination and at one time-point (2–8 months) after the last vaccination. An active lesion was defined as a T1w Gd enhanced lesion, or a new or enlarging T2w lesion. Lesions that appeared on T2w scans and were Gd enhanced on T1w were counted only once; n.a.: not applicable.

DISCUSSION

Our previous study with TCV using MBP-reactive T cells has shown that this procedure leads to an up-regulation of the regulatory anticlonotypic networks, and a specific suppression of the MBP-specific T cells in the periphery [9,35]. However, there are some limitations associated with this protocol of TCV using only MBP-specific T cell clones. Indeed, it has been demonstrated that the autoimmune response in MS is also directed to several other myelin antigens such as PLP and MOG [20,21,33]. This diverse T cell reactivity pattern might be present from disease onset and may persist along the disease progression, as shown in a study by Soderstrom and co-workers [27]. In contrast, recognition of multiple myelin antigens could also be the result of inter or intramolecular epitope spreading after breakdown of the blood–brain barrier and subsequent demyelination and release of myelin fragments [22,36]. These two mechanisms may account for the heterogeneous reactivity against multiple myelin antigens and should be taken into consideration when developing an improved T cell-specific therapy for MS. In addition, it has been shown that the frequency of myelin-reactive T cells is increased in the cerebrospinal fluid of MS patients [25–28]. Other studies have demonstrated a high frequency of activated CD4+ T cells in CSF and showed that certain T cell clones persist for a long time in the CSF, further supporting their relevance for the immunopathogenesis of MS [37,38]. In EAE studies, it has been demonstrated that, although the phenotype of T cells in the target organ diversifies as the disease progresses, disease-associated T cells are preserved throughout the course of the disease [39,40]. Furthermore, bystander CSF-derived cells attracted to the site of inflammation may also be potentially important in the disease process.

We carried out a CSF-derived T cell vaccination protocol based on the concept that CSF activated CD4+ T cells, recognizing a broad spectrum of myelin or other currently unidentified CNS antigens and bystander cells may be pathologically important in the disease process. We cultured CSF-derived mononuclear cells obtained from five MS patients with low doses of rhIL-2 to specifically expand activated T cells, bearing the IL-2 receptor [37]. Other cell populations were depleted using immunomagnetic beads (CD8+ T cells and γδ cells). Using this protocol CSF-based vaccines were generated from four of five MS patients. For one patient, CSF-derived T cells could not be expanded and instead we used IL-2 expanded T cells from the peripheral blood.

The majority of the CSF-T cell cultures consisted of activated cells, which was shown previously to be necessary for an efficient recognition by anti-idiotypic T cells in EAE. The T cells in the vaccines phenotypically resemble pathogenic myelin-reactive T cells described previously in EAE and MS: CD4+ T helper cells of Th1- or mixed Th0-subtype [41–43]. All CSF-derived T cells produced high levels of the proinflammatory cytokines TNF-α and IFN-γ. This production may be important as these cytokines have been shown to damage the myelin-producing oligodendrocytes, facilitate the recruitment of inflammatory cells to the site of inflammation by up-regulating the expression of adhesion molecules and lead to an increased presentation of CNS antigens after up-regulation of MHC class II molecules [44,45].

What is the composition of the CSF-based vaccines in terms of myelin-reactivity and clonal heterogeneity? As demonstrated by IFN-γ ELISPOT, all CSF-derived T cell vaccines displayed a heterogeneous reactivity towards MBP-, PLP- and MOG-peptides. However, we only tested reactivity to a limited number of immunodominant peptides of three myelin antigens. It remains possible that T cells, recognizing other epitopes of MBP, PLP and MOG or even other (unidentified) CNS antigens, may also be present. In addition, we demonstrated that the true frequency of cytokine-secreting T cells upon specific antigen stimulation may be underestimated using the ELISPOT-technique, as illustrated for pure CD4+ Th1 MBP- and MOG reactive T cell clones (data not shown). Semi-quantitative analysis of the TCR BV gene repertoire revealed that only a limited number of BV genes is overexpressed, although the identity of the predominant BV gene families varied between different MS patients. These findings do not agree fully with a previous study that reported a marked bias of TCR BV6 in expanded CSF samples for the majority of the MS patients screened [37]. CDR3 fragment length screening and CDR3 sequence analysis of specific BV genes demonstrated a restricted clonal composition with only one or a few dominant clonotypes within a given BV family. In addition, our data illustrate that clonal composition of the vaccines remained stable and dominant clones persisted during further culturing. In conclusion, our results demonstrate that the vaccines where composed of activated CD4+ Th1/0 cells with a limited clonal origin and with reactivity to different myelin antigens but also unidentified antigens.

Our data demonstrated a cellular proliferative response to the vaccines after immunization. From animal studies, we have learned that the T cell receptor (TCR) is the major target of both CD8+ MHC class I restricted and CD4+ MHC class II restricted anti-idiotypic T cells [46,47]. Based on T cell (receptor) vaccination studies in humans, it has been shown that the anti-idiotypic T cell responses are directed preferentially at the hypervariable CDR3 or the less variable CDR2 sequences of the idiotypic TCR [15,48–50]. Although TCR determinants may be the predominant targets, additional surface molecules may also contribute to the enhancement of the peripheral regulatory networks. Immune responses directed at activation markers common to all CD4+ T cells may also play an important role in the suppression of activated T cells following vaccination [7]. Although the targets for these T–T cell interactions remain unidentified, cytokine receptors have recently been proposed as candidate molecules [51]. Our data indicate that CSF-derived T cell vaccines are immunogenic because both anticlonotypic and antiergotypic responses are present after vaccination. Indeed, we observed proliferative responses to irradiated vaccine cells but also against irradiated autologous PHA-stimulated T cell blasts. These data correspond to our previous studies of TCV with MBP-reactive T cell clones: anticlonotypic T cell lines isolated from immunized patients were predominantly CD8+ cytolytic T cells that specifically recognized and lysed the immunizing T cell clones in the context of MHC class I molecules and CD4+ T cells were the major cytokine producing cells in the antivaccine cell population after TCV [13–15]. Furthermore, antiergotypic T cell responses have been demonstrated in almost all patients [12].

Interestingly, we found a significant reduction of MBP, PLP and MOG-reactive T cells in the periphery after TCV in two MS patients, while the frequency of TT-specific T cells remained the same. In the other three patients the antimyelin reactivity was rather low before vaccination and remained stable or was further reduced. Our results suggest that by enhancing the regulatory networks (both anticlonotypic and antiergotypic), the frequency of myelin-reactive T cells can be reduced by TCV. Furthermore, we were not able to successfully expand activated CD4+ T cells from the CSF after vaccination in the majority of the patients. It is tempting to speculate that CSF cultures either are depleted from activated T cells or are dominated by other cell subsets involved in the anticlonotypic and antiergotypic regulation of the pathogenic T cells. These findings are consistent with another T cell receptor vaccination study, where MS patients were immunized with a TCR BV6 peptide [52]. This BV gene family was overexpressed in the CSF-derived activated T cell population of the majority of the MS patients screened previously [37]. After vaccination, CSF cultures of some patients failed to expand in cytokine supplemented conditions and the authors proposed that the lack of cell growth might imply the absence of activated T cells in the CSF of these patients [52]. However, CDR3 sequence analysis to compare the clonal heterogeneity of cultured CSF and non-stimulated PBMC before and after vaccination in one MS patient revealed that T cell clones comprised in the CSF vaccines were still detectable: some clones persisted in the CSF and peripheral blood, although the frequency of other dominant T cell clones significantly diminished after vaccination. Despite the fact that this patient (AMH) showed an antivaccine response following vaccination, the number or immunogenicity of certain T cell clones in the CSF vaccines might be too low to induce a sufficient anticlonotypic response to (completely) eliminate these pathogenic T cells. These observations are in line with a previous report on TCR peptide vaccination: immunization with a low dosage of the TCR BV6 peptide did not reduce the frequency of TCR BV6-specific T cells after treatment. In contrast, the higher dose vaccination was more effective [52]. Another possibility to circumvent this problem is to perform repeated vaccinations (more than three) to obtain efficient immune responses towards all vaccine cells over time. It should also be noted that for one MS patient, we were not able to generate a CSF-derived T cell vaccine. Instead we used activated T cells from the blood, and both anticlonotypic and antiergotypic responses were detected after vaccination. In addition, we found a significant reduction of MBP, PLP and MOG-reactive T cells in the periphery. Although we presume that the frequency of pathogenic T cells is higher in the CSF, we have also demonstrated in patient AMH that activated T cell clones in the blood before vaccination can be detected in the CSF afterwards. Therefore, using these T cells as vaccines might prevent their migration to the CNS and subsequent pathological effects. The procedure for the generation of blood-derived activated CD4+ T cell vaccines is less complicated, but the relevance of these activated T cells to the disease is less clear. In conclu-sion, we demonstrated a significant immunological response both to the vaccine cells (anti-idiotypic) as well as to activated cells in general (antiergotypic), although T cell clones used in the CSF-derived vaccines were not completely eliminated after vaccination.

This pilot trial was not designed to draw conclusions about treatment efficacy, but preliminary data suggest some degree of clinical benefit for MS patients in terms of a reduced relapse rate and a stabilization of disease scores shortly after vaccination. Based on the promising results on feasibility and safety of this approach, together with the immune effects, a double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial involving 60 early RR-MS patients was recently initiated to study the efficacy of vaccination with CSF-derived T cells in a larger population.

Acknowledgments

We thank C. Bocken, E. Smeyers, J. Bleus, I. Rutten, D. Nijst, M. Bousse and A. Bogaers for excellent technical assistance and Dr A. VanderBorght and M. Buntinx for helpful discussions. This work was supported by grants from the Belgian ‘Instituut voor de bevordering van het Wetenchappelijk Technologisch Onderzoek in de Industrie (IWT)’ (‘Strategische technologieën voor Welzijn en Welvaart (STWW)’ programme), the Belgian ‘Nationaal Fonds voor Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek (FWO)’, the Belgian Charcot Foundation, the Belgian WOMS Foundation and the Limburgs Universitair Centrum (LUC). A. VdA holds a fellowship from the ‘Bijzonder Onderzoeksfonds’-LUC.

References

- 1.Martin R, McFarland HF, McFarlin DE. Immunological aspects of demyelinating diseases. Annu Rev Immunol. 1992;10:153–87. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.10.040192.001101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stinissen P, Raus J, Zhang J. Autoimmune pathogenesis of multiple sclerosis: role of autoreactive T lymphocytes and new immunotherapeutic strategies. Crit Rev Immunol. 1997;17:33–75. doi: 10.1615/critrevimmunol.v17.i1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hellings N, Raus J, Stinissen P. Insights into the immunopathogenesis of multiple sclerosis. Immunol Res. 2002;25:27–51. doi: 10.1385/IR:25:1:27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hohlfeld R. Biotechnological agents for the immunotherapy of multiple sclerosis. Principles, problems and perspectives. Brain. 1997;120:865–916. doi: 10.1093/brain/120.5.865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen IR. The cognitive paradigm and the immunological homunculus. Immunol Today. 1992;13:490–4. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(92)90024-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lider O, Reshef T, Beraud E, Ben Nun A, Cohen IR. Anti-idiotypic network induced by T cell vaccination against experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Science. 1988;239:181–3. doi: 10.1126/science.2447648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lohse AW, Spahn TW, Wolfel T, et al. Induction of the anti-ergotypic response. Int Immunol. 1993;5:533–9. doi: 10.1093/intimm/5.5.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hafler DA, Cohen I, Benjamin DS, Weiner HL. T cell vaccination in multiple sclerosis: a preliminary report. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1992;62:307–13. doi: 10.1016/0090-1229(92)90108-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang J, Medaer R, Stinissen P, Hafler D, Raus J. MHC-restricted depletion of human myelin basic protein-reactive T cells by T cell vaccination. Science. 1993;261:1451–4. doi: 10.1126/science.7690157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Correale J, Lund B, McMillan M, Ko DY, McCarthy K, Weiner LP. T cell vaccination in secondary progressive multiple sclerosis. J Neuroimmunol. 2000;107:130–9. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(00)00235-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Medaer R, Stinissen P, Truyen L, Raus J, Zhang J. Depletion of myelin-basic-protein autoreactive T cells by T-cell vaccination: pilot trial in multiple sclerosis. Lancet. 1995;346:807–8. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)91622-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stinissen P, Zhang J, Medaer R, Vandevyver C, Raus J. Vaccination with autoreactive T cell clones in multiple sclerosis: overview of immunological and clinical data. J Neurosci Res. 1996;45:500–11. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19960815)45:4<500::AID-JNR21>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stinissen P, Hermans G, Hellings N, Raus J. Functional characterization of CD8 anticlonotypic T cells from MS patients treated with T cell vaccination. J Neuroimmunol. 1998;90:99–564. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hermans G, Denzer U, Lohse A, Raus J, Stinissen P. Cellular and humoral immune responses against autoreactive T cells in multiple sclerosis patients after T cell vaccination. J Autoimmun. 1999;13:233–46. doi: 10.1006/jaut.1999.0314. 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang J, Vandevyver C, Stinissen P, Raus J. In vivo clonotypic regulation of human myelin basic protein-reactive T cells by T cell vaccination. J Immunol. 1995;155:5868–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hermans G, Medaer R, Raus J, Stinissen P. Myelin reactive T cells after T cell vaccination in multiple sclerosis: cytokine profile and depletion by additional immunizations. J Neuroimmunol. 2000;102:79–84. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(99)00157-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Genain CP, Nguyen MH, Letvin NL, et al. Antibody facilitation of multiple sclerosis-like lesions in a nonhuman primate. J Clin Invest. 1995;96:2966–74. doi: 10.1172/JCI118368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Markovic-Plese S, Fukaura H, Zhang J, et al. T cell recognition of immunodominant and cryptic proteolipid protein epitopes in humans. J Immunol. 1995;155:982–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pelfrey CM, Tranquill LR, Vogt AB, McFarland HF. T cell response to two immunodominant proteolipid protein (PLP) peptides in multiple sclerosis patients and healthy controls. Mult Scler. 1996;1:270–8. doi: 10.1177/135245859600100503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kerlero de Rosbo N, Milo R, Lees MB, Burger D, Bernard CC, Ben Nun A. Reactivity to myelin antigens in multiple sclerosis. Peripheral blood lymphocytes respond predominantly to myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein. J Clin Invest. 1993;92:2602–8. doi: 10.1172/JCI116875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Diaz-Villoslada P, Shih A, Shao L, Genain CP, Hauser SL. Autoreactivity to myelin antigens: myelin/oligodendrocyte glycoprotein is a prevalent autoantigen. J Neuroimmunol. 1999;99:36–43. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(99)00099-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hellings N, Gelin G, Medaer R, et al. Longitudinal study of antimyelin T-cell reactivity in relapsing- remitting multiple sclerosis: association with clinical and MRI activity. J Neuroimmunol. 2002;126:143–60. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(02)00052-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sun JB, Olsson T, Wang WZ, et al. Autoreactive T and B cells responding to myelin proteolipid protein in multiple sclerosis and controls. Eur J Immunol. 1991;21:1461–8. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830210620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sun J, Link H, Olsson T, et al. T and B cell responses to myelin-oligodendrocyte glycoprotein in multiple sclerosis. J Immunol. 1991;146:1490–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang J, Markovic-Plese S, Lacet B, Raus J, Weiner HL, Hafler DA. Increased frequency of interleukin 2-responsive T cells specific for myelin basic protein and proteolipid protein in peripheral blood and cerebrospinal fluid of patients with multiple sclerosis. J Exp Med. 1994;179:973–84. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.3.973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chou YK, Bourdette DN, Offner H, et al. Frequency of T cells specific for myelin basic protein and myelin proteolipid protein in blood and cerebrospinal fluid in multiple sclerosis. J Neuroimmunol. 1992;38:105–13. doi: 10.1016/0165-5728(92)90095-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Soderstrom M, Link H, Sun JB, Fredrikson S, Wang ZY, Huang WX. Autoimmune T cell repertoire in optic neuritis and multiple sclerosis: T cells recognising multiple myelin proteins are accumulated in cerebrospinal fluid. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1994;57:544–51. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.57.5.544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Soderstrom M, Link H, Sun JB, et al. T cells recognizing multiple peptides of myelin basic protein are found in blood and enriched in cerebrospinal fluid in optic neuritis and multiple sclerosis. Scand J Immunol. 1993;37:355–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.1993.tb02565.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Deibler GE, Martenson RE, Kies MW. Large scale preparation of myelin basic protein from central nervous tissue of several mammalian species. Preport Biochem. 1972;2:139–65. doi: 10.1080/00327487208061467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.VanderBorght A, Van der Aa A, Geusens P, Vandevyver C, Raus J, Stinissen P. Identification of overrepresented T cell receptor genes in blood and tissue biopsies by PCR-ELISA. J Immunol Meth. 1999;223:47–61. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(98)00201-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.VanderBorght A, Geusens P, Vandevyver C, Raus J, Stinissen P. Skewed T-cell receptor variable gene usage in the synovium of early and chronic rheumatoid arthritis patients and persistence of clonally expanded T cells in a chronic patient. Rheumatology (Oxf) 2000;39:1189–201. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/39.11.1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pannetier C, Cochet M, Darche S, Casrouge A, Zoller M, Kourilsky P. The sizes of the CDR3 hypervariable regions of the murine T-cell receptor beta chains vary as a function of the recombined germ-line segments. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:4319–23. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.9.4319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hellings N, Baree M, Verhoeven C, et al. T-cell reactivity to multiple myelin antigens in multiple sclerosis patients and healthy controls. J Neurosci Res. 2001;63:290–302. doi: 10.1002/1097-4547(20010201)63:3<290::AID-JNR1023>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kurtzke JF. Rating neurologic impairment in multiple sclerosis: an expanded disability status scale (EDSS) Neurology. 1983;33:1444–52. doi: 10.1212/wnl.33.11.1444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ben Nun A, Wekerle H, Cohen IR. Vaccination against autoimmune encephalomyelitis with T-lymphocyte line cells reactive against myelin basic protein. Nature. 1981;292:60–1. doi: 10.1038/292060a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tuohy VK, Yu M, Yin L, et al. The epitope spreading cascade during progression of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis and multiple sclerosis. Immunol Rev. 1998;164:93–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1998.tb01211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wilson DB, Golding AB, Smith RA, et al. Results of a phase I clinical trial of a T-cell receptor peptide vaccine in patients with multiple sclerosis. I. Analysis of T-cell receptor utilization in CSF cell populations. J Neuroimmunol. 1997;76:15–28. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(97)00028-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hafler DA, Fox DA, Manning ME, Schlossman SF, Reinherz EL, Weiner HL. In vivo activated T lymphocytes in the peripheral blood and cerebrospinal fluid of patients with multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 1985;312:1405–11. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198505303122201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim G, Kohyama K, Tanuma N, Arimito H, Matsumoto Y. Persistent expression of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE)-specific Vbeta8.2 TCR spectratype in the central nervous system of rats with chronic relapsing EAE. J Immunol. 1998;161:6993–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim G, Tanuma N, Kojima T, et al. CDR3 size spectratyping and sequencing of spectratype-derived TCR of spinal cord T cells in autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol. 1998;160:509–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zamvil SS, Steinman L. The T lymphocyte in experimental allergic encephalomyelitis. Annu Rev Immunol. 1990;8:579–621. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.08.040190.003051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hermans G, Stinissen P, Hauben L, Berg-Loonen E, Raus J, Zhang J. Cytokine profile of myelin basic protein-reactive T cells in multiple sclerosis and healthy individuals. Ann Neurol. 1997;42:18–27. doi: 10.1002/ana.410420106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hemmer B, Vergelli M, Calabresi P, Huang T, McFarland HF, Martin R. Cytokine phenotype of human autoreactive T cell clones specific for the immunodominant myelin basic protein peptide (83–99) J Neurosci Res. 1996;45:852–62. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19960915)45:6<852::AID-JNR22>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vartanian T, Li Y, Zhao M, Stefansson K. Interferon-gamma-induced oligodendrocyte cell death: implications for the pathogenesis of multiple sclerosis. Mol Med. 1995;1:732–43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Selmaj KW, Raine CS. Tumor necrosis factor mediates myelin and oligodendrocyte damage in vitro. Ann Neurol. 1988;23:339–46. doi: 10.1002/ana.410230405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Howell MD, Winters ST, Olee T, Powell HC, Carlo DJ, Brostoff SW. Vaccination against experimental allergic encephalomyelitis with T cell receptor peptides. Science. 1989;246:668–70. doi: 10.1126/science.2814489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vandenbark AA, Hashim G, Offner H. Immunization with a synthetic T-cell receptor V-region peptide protects against experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Nature. 1989;341:541–4. doi: 10.1038/341541a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chou YK, Buenafe AC, Dedrick R, et al. T cell receptor V beta gene usage in the recognition of myelin basic protein by cerebrospinal f. J Neurosci Res. 1994;37:169–81. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490370203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bourdette DN, Chou YK, Whitham RH, et al. Immunity to T cell receptor peptides in multiple sclerosis. III. Preferential immunogenicity of complementarity-determining region 2 peptides from disease-associated T cell receptor BV genes. J Immunol. 1998;161:1034–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zang YC, Hong J, Rivera VM, Killian J, Zhang JZ. Preferential recognition of TCR hypervariable regions by human anti-idiotypic T cells induced by T cell vaccination. J Immunol. 2000;164:4011–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.8.4011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mor F, Reizis B, Cohen IR, Steinman L. IL-2 and TNF receptors as targets of regulatory T–T interactions: isolation and characterization of cytokine receptor-reactive T cell lines in the Lewis rat. J Immunol. 1996;157:4855–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gold DP, Smith RA, Golding AB, et al. Results of a phase I clinical trial of a T-cell receptor vaccine in patients with multiple sclerosis. II. Comparative analysis of TCR utilization in CSF T-cell populations before and after vaccination with a TCRV beta 6 CDR2 peptide. J Neuroimmunol. 1997;76:29–38. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(97)00029-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]