Abstract

Both innate and adaptive immune systems are thought to participate in the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis in adults and children. The experiments reported here were undertaken to examine how immune complexes, potent stimulators of inflammation, may regulate cells of the adaptive immune system. Human T cells were prepared from peripheral blood by negative selection and incubated with bovine serum albumin (BSA)–anti-BSA immune complexes that were formed in the presence or absence of human C1q. C1q-bearing immune complexes, but not unopsonized complexes, elicited both TNF-α and IFN-γ secretion from human T cells. Secretion of both cytokines was time- and dose-dependent. Cross-linking C1q on the cell surface of T cells produced the same results. Cytokine secretion was not inhibited by blocking the C3b receptor (CR1, CD35) on T cells prior to incubation with immune complexes. Reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) of immune complex-stimulated cells revealed accumulation of both TNF-α and IFN-γ mRNA within 2 h post-stimulation. IL-2 was not detected in cell culture supernatants, but IL-2 receptor α chain (CD25) was detected in low density on a small proportion of T cells activated by C1q-bearing immune complexes. Secretion of both cytokines was inhibited partially, but not completely, by IL-10. These experiments show that immune complexes, potent inflammatory mediators, may activate T cells through a novel mechanism. These findings have implications for chronic inflammatory diseases in humans.

Keywords: C1q, IFN-γ, ΙL-10, IL-2 receptor, immune complexes, T cells, TNF-α

INTRODUCTION

T lymphocytes are important components in the initiation and amplification of the adaptive immune response. Conventional T cell activation involves the recognition of peptides or primary amino acid sequences presented within the grooves of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules of antigen-presenting cells. However, in addition to the antigen receptor/CD3 complex through which T cells can be activated by specific antigen, subsets of T cells also express receptors that are part of the innate immune system. For example, the C4b/C3b receptor, CR1 (CD35), is expressed on 10–15% of a subpopulation of T lymphocytes [1–3]. Similarly, subsets of CD8+ T cells express the iC3b receptor, CR3 (CD11b/CD18), which when activated also functions as a β2 integrin [4]. In addition, subpopulations of T cells express at least two cell-surface proteins that will bind C1q, a 60-kDa molecule that binds to the collagen-like region of C1q and a 33-kDa protein with affinity for the globular heads of C1q. These molecules, individually or in concert, may contribute to the C1q-mediated regulation of T cell activation and proliferation [5–7]. Furthermore, although most T cells do not express FcγR, small subpopulations of T cells expressing FcγR have been described [8,9]. Thus, although they play a central role in adaptive immunity, T cells, or subpopulations thereof, also express cell-surface receptors that allow interaction with and regulation by the innate immune system.

In the present study we investigated the ability of T cells to produce cytokines in response to C1q-bearing immune complexes, and to clarify the mechanisms through which such complexes activate T cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents

Polyclonal goat antihuman C1q and bovine serum albumin (BSA; obtained in fatty acid free form) were purchased from Sigma (St Louis, MO, USA). Rabbit polyclonal IgG anti-BSA antibody was obtained from ICN/Cappel (Durham, NC, USA). Purified human C1q was obtained from Advanced Research Technologies (San Diego, CA, USA). Murine 3D9 monoclonal antibody [10], which blocks function of CR1 (CD35), was a gift from Dr John Atkinson, Washington University, St Louis. Monoclonal antihuman TNF-α, IFN-γ and IL-2, HRP-conjugated polyclonal anti-TNF-α, IFN-γ and IL-2 and recombinant TNF-α, IFN-γ and IL-2 standards used for the ELISA assays were obtained from Pharmingen (San Diego, CA, USA). PE-conjugated antihuman CD25 antibodies were obtained from Pharmingen. RPMI-1640 media, l-glutamine, penicillin, streptomycin, fetal bovine serum (FBS) and Trizol were purchased from Gibco (Grand Island, NY, USA). TNF-α and IFN-γ primers were made by William K. Warren Medical Research Institute, University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center. Specific primers for β-actin were purchased from Clontech Laboratories (Palo Alto, CA, USA). PHA and Histopaque-1077 were purchased from Sigma. Recombinant IL-10 protein was purchased from Pharmingen. Oligo (dT)15 primers for reverse transcription reactions were obtained from Promega (Madison, WI, USA). Taq polymerase chain reaction (PCR) Master Mix Kit was purchased From Qiagen (Valencia, CA, USA). Microbeads conjugated with monoclonal mouse antihuman CD14, CD19, CD56 antibodies and MACs separation column were purchased from Miltenyi Biotech (Auburn, CA, USA).

Preparation of immune complexes

BSA–anti-BSA immune complexes (‘unopsonized complexes’) and C1q-bearing immune complexes were formed at 2× antigen excess as we have described previously [11]. The equivalence point was determined by a turbidometric assay described previously [12]. Briefly, immune complexes were formed by combining BSA (0·2 mg/ml), and anti-BSA (6·0 mg/ml) in the presence or absence of C1q (50 µg/ml) in PBS at 37°C for 1 h (the ratio of BSA to anti-BSA to provide 2× antigen excess varied with different lots of antibody). Insoluble material was removed by centrifugation. The complexes were separated from uncomplexed antigen and antibody by using size-exclusion chromatography on S-300 (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech AB, Sweden) equilibrated with PBS as described previously [13]. The exclusion volume, representing material ≥ 1·5 × 106 mol wt was saved and protein concentration of the immune complex preparations was estimated by measuring absorbance at 280 nm. Confirmation that immune complexes had fixed C1q was accomplished by Western blotting.

T cell preparation and stimulation

To avoid cell activation during purification, a negative sorting strategy was employed. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were prepared from heparinized venous blood obtained from healthy volunteers using gradient separation on Histopaque-1077. Cells were washed three times in Ca2+ and Mg2+-free Hanks's balanced salt solution. Cells were then placed in plastic dishes containing RPMI-1640 supplemented with penicillin G (100 U/ml), streptomycin (100 µg/ml), l-glutamine (2 mm) and 10% heat-inactivated FBS. Cells were incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 30 min, after which non-adherent cells were collected and incubated for 20 min at 4°C with CD14, CD19 and CD56 microbeads at 20 µl/1 × 107 cells. The cells were washed once, resuspended in 500 µl Ca2+ and Mg2+-free PBS containing 5% FBS/1 × 108 cells. The suspension was then applied to a MACs column and the unlabelled cells were collected. Cells prepared in this fashion were less than 1% CD14, CD56 and CD19-positive by fluorescence-activated cell-sorting (FACS) analysis.

The T cells were collected and diluted to a concentration of 2 × 106 cells/ml of medium (RPMI-1640) supplemented with penicillin G (100 U/ml), streptomycin (100 µg/ml), l-glutamine (2 mm) and 10% heat-inactivated FBS. Cells were stimulated with C1q-bearing immune complexes at concentrations ranging from 100 to 800 µg/ml for 36 h and time-courses ranging from 4 to 36 h at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. These immune complex concentrations were chosen as being within the range of immune complexes known to accumulate in the circulation in such divergent human illnesses as systemic lupus erythematosus [14], juvenile rheumatoid arthritis [15] and congenital HIV infection [16]. Thus, immune complexes were incubated with the cells at pathologically relevant concentrations. Medium was collected and stored at − 70°C until used for the measurement of TNF-α, IFN-γ and IL-2 concentrations.

A separate set of experiments was performed to identify the specificity of C1q as the entity within the immune complexes responsible for activating T cells. In these experiments, T cells were prepared exactly as described above and incubated with 10 µg/ml purified C1q for 1 h at 37°C. Surface-bound C1q was then cross-linked using 50 µg/ml polyclonal goat anti-C1q antibody. Cells were then incubated for 36 h, after which cell culture supernates were assayed for TNF-α by ELISA. In another set of experiments, T cells were preincubated with 10–20 µg 3D9 MoAb to CR1 (CD35), the C3b receptor which is expressed on a small subpopulation of T cells, prior to the addition of C1q-bearing immune complexes.

Cytokine measurement by ELISA

Concentrations of TNF-α, IFN-γ and IL-2 in cell culture supernates were determined by ELISA using commercially available antibodies. TNF-α MoAb, IFN-γ MoAb or IL-2 MoAb were coated overnight in 96-well microtitre plates in 0·1 m carbonate buffer (pH 9·5). Non-specific binding sites were blocked with 10% FBS in PBS. Cell culture supernates were diluted in PBS and 100 µl added to each well and incubated at room temperature (RT) for 2 h. Plates were then washed and incubated with biotinylated anti-TNF-α, IFN-γ and IL-2 detection antibody and avidin horseradish peroxidase conjugate for 1 h at room temperature, after which the plates were washed again. The colourimetric reaction was obtained with tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) and hydrogen peroxide. The reaction was stopped with 50 µl of 2 N H2 SO4. Plates were then read at 450 nm using a Biotek (Winooski, VT, USA) multiplate reader. Light absorbance from experimental samples was compared with a standard curve generated from known amounts of recombinant TNF-α, IFN-γ or IL-2 protein. Data were entered into a commercially available graphics statistical software program (GraphPad Prism, San Diego, CA, USA) and results obtained under different experimental conditions (e.g. presence and absence of IL-10) were compared by two-tailed independent t-test. P-values < 0·05 were considered statistically significant.

FACS analysis of IL-2 receptorαchain expression

T cells were incubated with C1q-bearing immune complexes (400 µg/ml) or PHA (10 ng/ml) for 36 h. Cells were collected and washed three times with staining medium, PBS containing 1% FBS. Cells (1 × 106 per sample) were stained at 4°C. Cell surface IL-2 receptor was detected by FACScan (Becton Dickinson, USA) using the PE-conjugated anti-CD25 antibodies. Negative controls consisted of PE-conjugated mouse IgG1, κ.

Reverse transcriptase PCR for TNF-α and IFN-γ mRNA

T cells were incubated with C1q-bearing immune complexes, 400 µg/ml, for time periods ranging from 2 to 24 h. Medium was then removed and cells lysed with Trizol reagent. Total RNA was extracted exactly as recommended by the manufacturer. RNA (1 µg) was transcribed into cDNA using oligo(dT)15 primers exactly as recommended by the manufacturer. Specific primers were constructed from known cDNA sequences of TNF-α (sense, 5′-ACAAGCCTGTAGCCCATGTT-3′; antisense, 5′-AAAGTAGACCTGCCCAGACT-3′) and IFN-γ (sense, 5′-GCAGAGCCAAATTGTCTCCT-3′; antisense, 5′-ATGCTC TTCGACCTCGAAAC-3′). Primers for amplification of β-actin were obtained from Clontech Laboratories, Inc. (Palo Alto, CA, USA). Each cDNA was amplified by PCR with Taq PCR Master Mix Kit. Amplification reactions were performed as follows: 1 × (94°C, 1 min), 26× (94°C, 20 s, 55°C, 20 s and 72°C 40 s); and 1× (72°C, 10 min). Products were analysed on a 1·5% agarose gel that contained ethidium bromide. Expected size for the PCR products for TNF-α, IFN-γ and β-actin were 427, 290 and 838 bp, respectively.

RESULTS

Immune complex stimulation of T cells

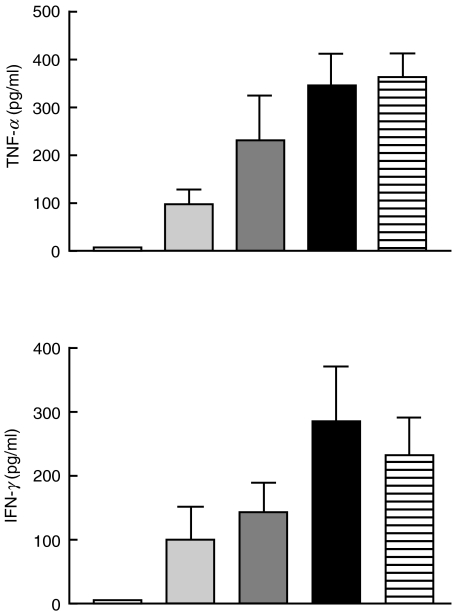

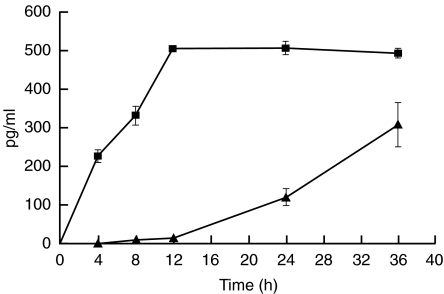

T cells treated with soluble C1q-bearing immune complexes (100–800 µg/ml) for 36 h secreted TNF-α and IFN-γ in a dose-dependent manner, as shown in Fig. 1. IL-2 was not detected. The kinetics of secretion differed for TNF-α compared with IFN-γ. TNF-α was detectable in the cell culture supernatants within 4 h after stimulation, and increased until 12 h. In contrast, IFN-γ was detectable within 8 h after stimulation, and continued to rise steadily until 36 h, the last time-point measured, as shown in Fig. 2. Neither BSA–anti-BSA immune complexes formed in the absence of C1q nor LPS (maximum concentration, 10 ng/ml) stimulated T cell secretion of TNF-α or IFN-γ (data not shown). Furthermore, neither IFN-γ nor TNF-α was secreted when T cells were incubated with insoluble complexes formed in the presence of either human serum or purified C1q (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

Dose-dependent production of TNF-α and IFN-γ by T cells after incubation 36 h with increasing concentrations of C1q-bearing immune complexes. Using a special ELISA, the concentration of TNF-α and IFN-γ was measured in the supernatants. Results are means ± s.e.m. of five independent experiments. □, C1qIC 0 µg/ml;  , C1qIC 100 µg/ml;

, C1qIC 100 µg/ml;  , C1qIC 200 µg/ml; ▪, 400 µg/ml;

, C1qIC 200 µg/ml; ▪, 400 µg/ml;  , 800 µg/ml.

, 800 µg/ml.

Fig. 2.

Kinetics of TNF-α and IFN-γ secretion by T cells after incubation with C1q-bearing immune complexes. T cells were incubated with 400 µg/ml C1q-bearing immune complexes for time periods ranging from 4 to 36 h. IFN-γ secretion lagged significantly behind TNF-α secretion. Results are means ± s.e.m. of three independent experiments. ▪, TNF; ▴, IFN.

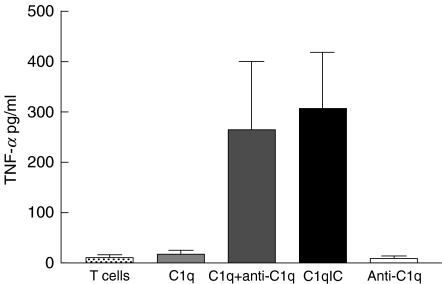

In a separate set of experiments, T cells were incubated with monomeric human C1q, followed by polyclonal goat antihuman C1q antibody. Results of these experiments are shown in Fig. 3. T cells incubated under these conditions produced TNF-α at levels comparable to T cells incubated with C1q immune complexes. Monomeric C1q had no effect on T cells. Blocking CR1 (CD35) with 3D9 MoAb had no effect on the capacity of C1q-bearing immune complexes to induce cytokine secretion from T cells (data not shown).

Fig. 3.

Cross-linking surface-bound C1q results in TNF-α secretion from T cells. T cells were preincubated with either C1q immune complexes (‘C1qIC’) or purified human C1q followed by polyclonal anti-C1q antibody (‘C1q + anti-C1q’) as described in the Methods section. TNF-α secretion was induced under both experimental conditions. Neither monomeric C1q (‘C1q’) nor polyclonal anti-C1q antibody (‘anti-C1q’) induced TNF-α secretion.  , T cells;

, T cells;  , C1q;

, C1q;  , C1q + anti-C1q; ▪, C1qIC; □, anti-C1q.

, C1q + anti-C1q; ▪, C1qIC; □, anti-C1q.

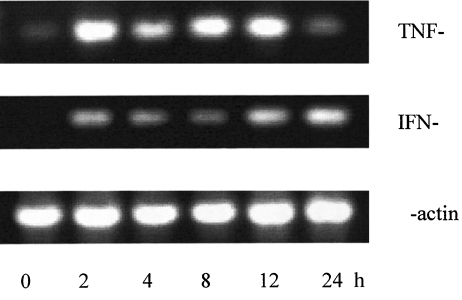

Induction of TNF-α, IFN-γ mRNA

Figure 4 shows a representative RT-PCR analysis of TNF-α and IFN-γ mRNA expression in T cells stimulated with C1q-bearing immune complexes. Neither TNF-α nor IFN-γ mRNA were detected in unstimulated T cells, but were detectable in immune complex stimulated T cells as early as 2 h after stimulation.

Fig. 4.

Accumulation of TNF-α and IFN-γ mRNA after stimulation of T cells by C1q-bearing immune complexes. RT-PCR was performed on RNA isolated from T cells that were stimulated for 2–24 h with C1q-bearing immune complexes (400 µg/ml) using specific primers for TNF-α (top panel) and IFN-γ (middle panel) and β-actin (lower panel). An aliquot of the PCR product was analysed by agarose gel electrophosis. Time periods (h) are indicated on the bottom line.

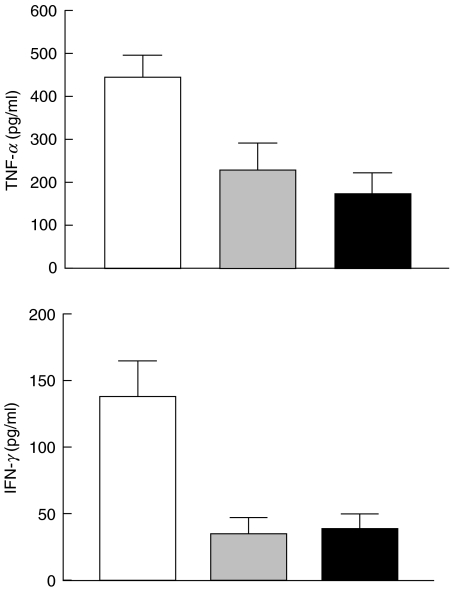

Inhibition of T cell TNF-α and IFN-γ secretion by IL-10

IL-10 is a potent inhibitor of leucocyte cytokine synthesis, acting mainly at the level of cytokine gene transcription. To determine whether the observed production of TNF-α or IFN-γ can be inhibited by IL-10, T cells were incubated with C1q-bearing immune complexes in the presence and absence of IL-10. The concentrations of TNF-α and IFN-γ were measured by ELISA and results are depicted in Fig. 5. IL-10 decreased TNF-α in the two concentrations tested (20 ng/ml and 100 ng/ml), but did not completely inhibit secretion even at the higher concentration. At 20 ng/ml, IL-10 inhibited TNF-α secretion by 49% (228 + 63 pg/ml versus 445 + 51 pg/ml; P < 0·001). Increasing the concentration to 100 ng/ml led to marginal decreases in TNF-α concentrations which were statistically significant compared with cells incubated in the absence of IL-10 (172 + 50 pg/ml versus 445 + 51 pg/ml; P < 0·001), but not cells incubated at 20 ng/ml (P > 0·05).

Fig. 5.

Reduction of TNF-α and IFN-γ secretion by IL-10 in T cells stimulated with C1q-bearing immune complexes. T cells were incubated with immune complexes in the presence or absence of IL-10. Mean production ± s.e.m. is shown for three independent experiments. □, C1qIC 400 µg/ml;  , IL-20 20 ng/ml + C1qIC; ▪, IL-10 100 ng/ml + C1qIC.

, IL-20 20 ng/ml + C1qIC; ▪, IL-10 100 ng/ml + C1qIC.

IL-10 was more efficient in inhibiting IFN-γ secretion. At 20 ng/ml, IL-10 inhibited IFN-γ secretion by 75% (35 + 12 pg/ml versus 137 + 26 pg/ml; P < 0·001). Increasing the concentration of IL-10 had no further effects on IFN-γ secretion by immune complex-stimulated T cells.

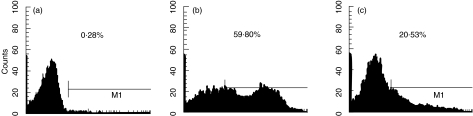

IL-2 receptor expression

T cells were incubated with C1q-bearing immune complexes or PHA for 36 h. Cells were stained and cell surface IL-2 receptor detected by FACs using the PE-conjugated anti-CD25 antibodies. A small proportion of T cells activated by C1q-bearing immune complexes expressed IL-2 receptor (CD25) in low density (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

FACs profiles for CD25 expression on T cells. The horizontal axis represents the intensity of CD25 staining by CD25+ gated cells. Percentages of CD25+ cells (from the total number of T cells) are also shown. Cells were stained with PE-conjugated mouse antihuman CD25 MoAb. (a) Resting T cells. (b) T cells were treated with PHA (10 ng/ml) for 36 h. (c) T cells were treated with C1q-bearing immune complexes (400 µg/ml) for 36 h.

DISCUSSION

The formation of circulating immune complexes is the physiological consequence of antibody responses to different antigens, including microorganisms [17] and intricate mechanisms for immune complex clearance have developed in mammals [18]. Thus, although immune complex formation is a physiological event, their accumulation in the tissue or circulation, as seen in such disorders as rheumatoid arthritis [19] or systemic lupus erythematosus [20], can be considered pathological. Immune complex accumulation leads to a broad spectrum of proinflammatory effects, including complement activation with release of phlogistic C3a and C5a peptides [21] and cytokine secretion from FcγR-expressing cells [22]. We now report a novel property of immune complexes that casts new light on chronic inflammatory diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis: activation of T lymphoctyes.

‘Conventional’ activation of T cells is induced through the TCR/CD3 signalling complex [23]. Such activation results in T cell proliferation [24,25], secretion of IL-2 and IFN-γ and expression of IL-2 receptor [26–28]. Although rheumatoid arthritis has been seen classically as a disease of disordered T cell activation, the cells infiltrating the rheumatoid synovium do not display the same phenotype as cells activated through the TCR/CD3 complex in vitro[29,30]. Specifically, cells in the rheumatoid synovium show no or little cell-surface expression of CD25 and do not secrete IL-2 [31,32]. However, T cells in rheumatoid synovium do secrete low levels of IFN-γ[33] and local TNF-α expression has been described in T cells in both adults [34] and children [35–37] with rheumatoid disease. It is interesting to note, therefore, that the phenotype demonstrated by the T cells in our experiments faithfully mimics what has been described in these related forms of chronic arthritis.

Our model also mimics another important feature of rheumatoid disease: a critical regulatory role for IL-10 [38]. Interleukin 10 is a 18-kDa non-glycosylated polypeptide secreted by monocytes/macrophages, B lymphocytes, keratinocytes, mast cells and subclasses of CD4+ T lymphocytes [39–42]. It possesses strong anti-inflammatory activity, largely by inhibiting proinflammatory cytokine synthesis in both lymphocytes and monocytes [43–45] through both transcriptional and post-transcriptional mechanisms [46–48]. In addition, IL-10 inhibits CXCR4-induced chemotaxis in T cells [49]. It is expressed locally in rheumatoid joints [50–52] and may serve as a pretreatment prognostic marker [53]. Current theories suggest that IL-10, secreted by macrophages and/or T cells, may serve as an autocrine regulator of those cells, dampening the intensity of the inflammatory response and minimizing local tissue destruction [54].

We have not identified clearly the specific cell surface receptor(s) on T cells that mediate cytokine secretion by immune complexes. Our experiments demonstrate that the relevant receptor is a C1q receptor, as unopsonized BSA–anti-BSA complexes had no effect on resting T cells. As we noted in our introduction, there are several receptors for complement proteins expressed on the surface of resting T cells. These include at least two receptors for C1q, although the functional characteristics of these receptors have not been clarified. T cells also express the C3b/C4b receptor, CR1 (CD35), which also binds C1q-bearing ligands [55]. Mouse homologues of the human receptor have been shown recently to enhance CD3-mediated T cell activation [56]. Because blocking this receptor with 3D9 MoAb failed to inhibit TNF-α secretion, we conclude that CR1 is not the receptor involved in T cell activation through this pathway.

Although conventional theories of the pathogenesis of both rheumatoid arthritis and juvenile rheumatoid arthritis [57] have focused on adaptive immunity and the role of the T cell in disease pathogenesis, it is becoming recognized increasingly that the pathogenesis of these illnesses very probably involves complex interactions between innate and adaptive immunity [58]. Furthermore, emerging evidence demonstrates that T cells can be activated to produce cytokines by mechanisms other than ‘classical’ activation though the CD3/TCR complex. For example, Tennenberg and colleagues [59] have demonstrated that LPS-activated endothelium, in the absence of monocytes or any other source of stimulation, can activate resting lymphocytes. Such data, as well as the experiments we report here, invite us to rethink the aetiological clue that is provided to us by the presence of CD4+ T cells within inflamed synovium in rheumatoid arthritis and juvenile rheumatoid arthritis.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (no. R01-AR43967) and the Children's Medical Research Foundation of Oklahoma. Thanks to Dr Anne Pereira for her review of this manuscript and to Julie McGhee for her careful proofreading of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Yaskanin DD, Thompson LF, Waxman FJ. Distribution and quantitative expression of the complement receptor type 1 (CR1) on human peripheral blood T lymphocytes. Cell Immunol. 1992;142:159–76. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(92)90277-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rodgaard A, Thomsen BS, Bendtzen K. Increased expression of complement receptor type 1 (CR1, CD35) on human peripheral blood T lymphocytes after polyclonal activation in vitro. Immunol Res. 1995;14:69–76. doi: 10.1007/BF02918498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mouhoub A, Delibrias CC, Fisher E, Boyer V, Kazatchkine MD. Ligation of CR1 (C3b receptor, CD35) on CD4+ T lymphocytes enhances viral replication in HIV-infected cells. Clin Exp Immunol. 1996;106:297–303. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1996.d01-844.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ross GD, Vetvicka V. CR3 (CD11b/CD18): a phagocyte and NK cell membrane receptor with multiple ligand specificities and functions. Clin Exp Immunol. 1993;92:181–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1993.tb03377.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen A, Gaddipati S, Hong Y, Volkman DJ, Peerschke EI, Ghebrehiwet B. Human T cells express specific binding sites for C1q. Role in T cell activation and proliferation. J Immunol. 1994;153:1430–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ghebrehiwet B, Lu PD, Zhang W, et al. Evidence that the two C1q binding membrane proteins, gC1q-R and cC1q-R, associate to form a complex. J Immunol. 1997;159:1429–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ghebrehiwet B, Habicht GS, Beck G. Interaction of C1q with its receptor on cultured cell lines induces an anti-proliferative response. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1990;54:148–60. doi: 10.1016/0090-1229(90)90014-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lanier LL, Kipps TJ, Phillips JH. Functional properties of a unique subset of cytotoxic T lymphocytes that express Fc receptors for IgG (CD16-Leu-11 antigen) J Exp Med. 1985;162:2089–106. doi: 10.1084/jem.162.6.2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Petrini M, Galbraith RM, Emerson DL, Nel AE, Arnaud P. Structural studies of T lymphocyte Fc receptors. Association of Gc protein with IgG binding to Fc gamma. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:1804–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nickells M, Hauhart R, Krych M, et al. Mapping epitopes for 20 monoclonal antibodies to CR1. Clin Exp Immunol. 1998;112:27–33. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1998.00549.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xiao S, Xu C, Jarvis JN. C1q-bearing immune complexes induce IL-8 secretion in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) through protein tyrosine kinase and mitogen-activated protein kinase-dependent mechanisms: evidence that the 126 kD phagocytic C1qreceptor mediates immune complex activation of HUVEC. Clin Exp Immunol. 2001;125:360–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2001.01597.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jarvis JN, Xu C-S, Wang W. Immune complex size and complement regulate cytokine production by peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Clin Immunol. 1999;93:274–82. doi: 10.1006/clim.1999.4792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Amit A, Kindzelskii AL, Zanoni J, Jarvis JN, Petty HR. Complement deposition on immune complexes reduces the frequencies of metabolic, proteolytic, and superoxide oscillations of migrating neutrophils. Cell Immunol. 1999;194:47–53. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1999.1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huber C, Roger A, Herrman M, Krapf F, Kalden JR. C3-containing serum immune complexes in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. correlation to disease activity and comparison with other rheumatic diseases. Rheumatol Int. 1989;9:59–64. doi: 10.1007/BF00270246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jarvis JN, Taylor H, Iobidze M, Krenz M. Complement activation and immune complexes in children with polyarticular JRA: a longitudinal study. J Rheumatol. 1994;21:1124–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jarvis JN, Taylor H, Iobidze M. Complement activation and immune complexes in early congenital HIV infection. J Acq Immune Def Syndr Retrovirol. 1995;8:480–5. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199504120-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schifferli JA, Taylor RP. Physiological and pathological aspects of circulating immune complexes. Kidney Int. 1989;35:993–1003. doi: 10.1038/ki.1989.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schifferli JA. Complement and immune complexes. Res Immunol. 1996;147:109–10. doi: 10.1016/0923-2494(96)87183-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jarvis JN, Diebold MM, Chadwell MK, Iobidze M, Moore HT. Composition and biological behavior of immune complexes isolated from synovial fluid of patients with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis (JRA) Clin Exp Immunol. 1995;100:514–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1995.tb03731.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Greisman SG, Redechan PB, Kimberley RP, Christian CI. Differences among immune complexes: association of C1q in SLE immune complexes with renal disease. J Immunol. 1987;138:739–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schifferli JA, Steiger G, Paccaud JP. Complement mediated inhibition of immune precipitation and solubilization generate different concentrations of complement anaphylatoxins (C4a, C3a, C5a) Clin Exp Immunol. 1986;64:407–14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jarvis JN, Wang W, Moore HT, Zhao L, Xu C-S. In vitro induction of proinflammatory cytokine secretion by juvenile rheumatoid arthritis synovial fluid immune complexes. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40:2039–46. doi: 10.1002/art.1780401117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ullman KS, Northrop JP, Verweij CL, Crabtree GR. Transmission of signals from the T lymphocyte antigen receptor to the genes responsible for cell proliferation and immune function: the missing link. Ann Rev Immunol. 1990;8:421–52. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.08.040190.002225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Feldmann M, Brennan FM, Maini RN. Role of cytokines in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rev Immunol. 1996;14:397–440. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.14.1.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moulton PJ. Inflammatory joint disease: the role of cytokines, cyclooxygenases and reactive oxygen species. Br J Biomed Sci. 1996;53:317–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weiss A, Littman DR. Signal transduction by lymphocyte antigen receptors. Cell. 1994;76:263–74. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90334-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Altman A, Coggeshall KM, Mustelin T. Molecular events mediating T cell activation. Adv Immunol. 1990;48:227–360. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60756-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harris ED., Jr Rheumatoid arthritis. Pathophysiology and implications for therapy. N Engl J Med. 1990;322:1277–89. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199005033221805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Panayi GS, Lanchbury JS, Kingsley GH. The importance of the T cell in initiating and maintaining the chronic synovitis of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1992;35:729–35. doi: 10.1002/art.1780350702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Taub DD, Conlon K, Lloyd AR, Openheim JJ, Kelvin DJ. Preferential migration of activated CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in response to MIP1 and MIP1β. Science. 1993;260:355–8. doi: 10.1126/science.7682337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Firestein GS, Xu WD, Townsend K, et al. Cytokines in chronic inflammatory arthritis. I. Failure to detect T cell lymphokines (interleukin-2 and interleukin-3) and presence of macrophage colony-stimulating factor (CSF-1) and a novel mast cell growth in rheumatoid synovitis. J Exp Med. 1988;168:1573–86. doi: 10.1084/jem.168.5.1573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen E, Keystone EC, Fish EN. Restricted cytokine expression in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1993;36:901–10. doi: 10.1002/art.1780360706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Simon AK, Seipelt E, Sieper J. Divergent T cell cytokine patterns in inflammatory arthritis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:8562–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.18.8562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chu CQ, Field M, Feldmann M, Maini RN. Localization of tumor necrosis factor α in synovial tissues and at the cartilage-pannus junction in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1991;34:1125–32. doi: 10.1002/art.1780340908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eberhard BA, Laxes RM, Andersson U, Silverman ED. Local synthesis of both macrophage and T cell cytokines by synovial fluid cells from children with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Immunol. 1994;96:260–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1994.tb06551.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lepore L, Pennesi M, Saletta S, Perticarari S, Presani G, Prodan M. Study of IL-2, IL-6, TNF-α, IFN-γ and β in the serum and synovial fluid of patients with juvenile chronic arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 1994;12:561–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grom AA, Murray KJ, Luyrin L, et al. Patterns of expression of tumor necrosis factor α, tumor necrosis factor β, and their receptors in synovia of patients with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis and juvenile spondyloarthropathy. Arthritis Rheum. 1996;39:1703–10. doi: 10.1002/art.1780391013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Katsikis PD, Chu C-Q, Brennan FM, Maini RN, Feldmann M. Immunoregulatory role of interleukin 10 in rheumatoid arthritis. J Exp Med. 1994;179:1515–27. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.5.1517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Go NF, Castle BE, Barrett R, et al. Interleukin 10, a novel B cell stimulatory factor: unresponsiveness of X chromosome-linked immunodeficiency B cells. J Exp Med. 1990;172:1625–31. doi: 10.1084/jem.172.6.1625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thompson L, Dhar LV, Bond MW, Mosmann TR, Moore KW, Rennick DM. Interleukin 10. a novel stimulatory factor for mast cells and their progenitors. J Exp Med. 1991;173:507–10. doi: 10.1084/jem.173.2.507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Waal Malefyt R, Abrams J, Bennet B, Figdor CG, de Vries JE. Interleukin 10 (IL-10) inhibits cytokine synthesis by human monocytes: an autoregulatory role of IL-10 produced by monocytes. J Exp Med. 1991;174:1209–20. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.5.1209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moore KW, de Waal Malefyt R, Coffmann RL, O'Garra A. Interleukin-10 and the interleukin 10 receptor. Ann Rev Immunol. 2001;19:683–765. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.de Waal Malefyt R, Yssel H, de Vries JE. Direct effects of IL-10 on subsets of human CD4+ T cell clones and resting T cells. J Immunol. 1993;150:4754–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Taga K, Mostowski H, Tosato G. Human interleukin-10 can directly inhibit T cell growth. Blood. 1993;81:2964–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schandene L, Alonso-Vega C, Willems F, et al. MB7/CD28-dependent IL-5 production by human resting T cells is inhibited by IL-10. J Immunol. 1994;152:4368–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Clarke CJ, Hales A, Hunt A, Foxwell BM. IL-10-mediated suppression of TNF-alpha production is independent of its ability to inhibit NF kappa B activity. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:1719–26. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199805)28:05<1719::AID-IMMU1719>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Aste-Amezaga M, Ma X, Sartori A, Trinchieri G. Molecular mechanisms of the induction of IL-12 and its inhibition by I L-10. J Immunol. 1998;160:5936–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brown CY, Lagnado CA, Vadas MA, Goodall GJ. Differential regulation of the stability of cytokine mRNAs in lipopolysaccharide-activated blood monocytes in response to interleukin-10. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:20108–12. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.33.20108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jinquan T, Quan S, Jacobi HH, et al. CXC chemokine receptor 4 expression and stromal cell-derived factor-1alpha-induced chemotaxis in CD4+ T lymphocytes are regulated by interleukin-4 and interleukin-10. Immunology. 2000;99:402–10. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2000.00954.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Llorente L, Richaud-Patin Y, Fior R, et al. In vivo production of interleukin-10 by non-T cells in rheumatoid arthritis, Sjogren' syndrome, and systemic lupus erythematosus: a potential mechanism of B lymphocyte hyperactivity and autoimmunity. Arthritis Rheum. 1994;37:1647–55. doi: 10.1002/art.1780371114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cohen SB, Katsikis PD, Chu CQ, et al. High level of interleukin-10 production by the activated T cell population within the rheumatoid synovial membrane. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38:946–52. doi: 10.1002/art.1780380710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cush JJ, Splawski JB, Thomas R, et al. Elevated interleukin-10 levels in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38:96–104. doi: 10.1002/art.1780380115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Verhoef CM, van Roon JA, Vianen ME, Bijlsma JW, Lafeber FP. Interleukin 10 (IL-10), not IL-4 or interferon-gamma production, correlates with progression of joint destruction in rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2001;28:1960–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.van Roon JAG, Lafeber FPJG, Bijlsma JWJ. Synergistic activity of interleukin-4 and interleukin-10 in suppression of inflammation and joint destruction in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44:3–10. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200101)44:1<3::AID-ANR2>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Klickstein LB, Barbashov SF, Liu T, Jack RM, Nicholson-Weller A. Complement receptor type 1 (CR1, CD35) is a receptor for C1q. Immunity. 1997;7:345–55. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80356-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fernandez-Centeno E, de Ojeda G, Rojo JM, Portoles P. Crry/p65, a membrane complement regulatory protein, has costimulatory properties on mouse T cells. J Immunol. 2000;164:533–42. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.9.4533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Grom AA, Giannini EH, Glass DN. Juvenile rheumatoid arthritis and the trimolecular complex (HLA, T cell receptor, and antigen). Differences from rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1994;37:601–7. doi: 10.1002/art.1780370501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Arend WP. The innate immune system in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44:2224–34. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200110)44:10<2224::aid-art384>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tennenberg SD, Weller JJ. Endotoxin activates T cell interferon-γ secretion in the presence of endothelium. J Surg Res. 1996;63:73–6. doi: 10.1006/jsre.1996.0225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]