Abstract

Dendritic cells (DCs) are the most potent antigen-presenting cells and a prerequisite for the initiation of primary immune response. This study was performed to investigate the contribution of DCs to the initiation of Graves’ hyperthyroidism, an organ-specific autoimmune disease in which the thyrotrophin receptor (TSHR) is the major autoantigen. DCs were prepared from bone marrow precursor cells of BALB/c mice by culturing with granulocyte macrophage-colony stimulating factor and interleukin−4. Subcutaneous injections of DCs infected with recombinant adenovirus expressing the TSHR (but not β-galactosidase) in syngeneic female mice induced Graves’-like hyperthyroidism (8 and 35% of mice after two and three injections, respectively) characterized by stimulating TSHR antibodies, elevated serum thyroxine levels and diffuse hyperplasitc goiter. TSHR antibodies determined by ELISA were of both IgG1 (Th2-type) and IgG2a (Th1-type) subclasses, and splenocytes from immunized mice secreted interferon-γ (a Th1 cytokine), not interleukin-4 (a Th2 cytokine), in response to TSHR antigen. Surprisingly, IFN-γ secretion, and induction of antibodies and disease were almost completely suppressed by co-administration of alum/pertussis toxin, a Th2-dominant adjuvant, whereas polyriboinosinic polyribocytidylic acid, a Th1-inducer, enhanced splenocyte secretion of IFN-γ without changing disease incidence. These observations demonstrate that DCs efficiently present the TSHR to naive T cells to induce TSHR antibodies and Graves’-like hyperthyroidism in mice. In addition, our results challenge the previous concept of Th2 dominance in Graves’ hyperthyroidism and provide support for the role of Th1 immune response in disease pathogenesis.

Keywords: autoimmunity, dendritic cells Graves’ disease, thyrotrophin receptor, Th1/Th2

Introduction

Graves’ disease is a tissue specific autoimmune disease of the thyroid gland characterized by hyperthyroidism mediated by thyroid stimulating autoantibodies. It is well established that the main autoantigen recognized by the autoimmune response in Graves’ disease is the thyrotrophin receptor (TSHR) [1,2]. However, despite extensive studies over decades, the precise mechanisms responsible for breaking tolerance remain to be elucidated. Aberrant MHC class II expression on thyroid epithelial cells in autoimmune thyroid disease was demonstrated first by Bottazzo et al. [3]. It is therefore proposed that thyroid cells expressing both TSHR and MHC class II probably play a role in the induction and/or exacerbation of autoimmune thyroid disease as non-professional antigen-presenting cells (APCs). This concept was supported later by the animal model of Graves’ disease developed by Shimojo et al. [4]. In contrast, dendritic cells (DCs) are well known to be professional APCs that can elicit a primary immune response and boost the secondary immune response to foreign antigens and autoantigens [5]. Indeed, DCs pulsed with autoantigens have been demonstrated previously to induce autoimmune diseases such as experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis and autoimmune diabetes [6,7]. In addition, it is reported that intrathyroidal infiltration of DCs and macrophages precedes lymphocytic involvements in animal models that develop lymphocytic thyroiditis spontaneously [8–11]. DC infiltration is also found in Graves’ and Hashimoto's thyroid tissues [12–14]. Therefore, it is possible that thyroid autoimmunity is initiated by thyroid infiltrating DCs that phagocytose and process thyroid autoantigens for presentation to T cells.

The present study was designed to examine the role of DCs in the induction of Graves’ hyperthyroidism. We demonstrate that repeated immunization of female BALB/c mice with syngeneic bone marrow-derived DCs infected with recombinant adenovirus expressing the TSHR induces Graves’-like hyperthyroidism. Disease is characterized by elevated serum thyroxine (T4) levels, positive thyroid stimulating and TSH binding inhibiting activities, and diffuse hyperplastic goitre. Surprisingly, this disease induction was suppressed completely by co-administration of alum and pertussis toxin (a Th2 adjuvant) but not by polyriboinosinic polyribocytidylic acid (poly (I:C), a Th1 adjuvant). These data suggest that (i) DCs may play a role in the initiation of Graves’ disease and (ii) Graves’ disease is not, as considered previously, a Th2-mediated autoimmune disease; both Th1 and Th2 immune responses appear to participate in the pathogenesis of disease.

Materials And Methods

Recombinant adenoviruses used

Recombinant adenoviruses expressing human TSHR (AdCMVTSHR) or β-galactosidase (AxCALacZ) have been constructed previously [15]. Amplification and purification of adenovirus, and spectrophotometrical determination of virus particle titre were performed as described previously [15].

Generation of bone marrow-derived DCs

Bone marrow-derived DCs were obtained from murine bone marrow precursors as described previously [16]. Briefly, bone marrow cells were harvested from femurs and tibias of ∼ 4 weeks old BALB/c mice (Charles River Japan Laboratory Inc., Tokyo, Japan) and plated in RPMI-1640 medium with 10% fetal calf serum, 50 µm 2-mercaptoethanol, antibiotics and 10 ng/ml recombinant murine granulocyte macrophage-colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF) (Kirin Brewery Co., Tokyo, Japan) and 10 ng/ml murine interleukin-4 (IL-4) (Wako Chemical Co., Osaka, Japan). The medium was changed every other day. Seven days later, non-adherent cells (immature DCs) were harvested by gentle washing with warm PBS. Flow cytometric analysis of CD11c, MHC class II and CD86 expression verified the purity of DCs to be >90% (data not shown).

X-gal staining

DCs, seeded at 1 × 105 cells per well in a 24-well culture plate, were infected with AxCALacZ at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10 000 particles per cell under centrifugation at 2000 g at 37°C for 2 h, as recommended recently [17]. One day later, the cells were stained with 5-bromo-4-chloro-indolyl-b-D-galactopyranoside (x-gal) as reported previously [18].

Flow cytometry

DCs, seeded at 1 × 106 cells per well in a 6-well culture plate, were infected with AdCMVTSHR at a MOI of 10 000 particles per cell under centrifugation at 2000 g at 37°C for 2 h [17]. One day later, flow cytometric analysis was performed as described previously [19]. Briefly, the cells were incubated for 30 min at room temperature with 1 : 100 diluted sera from a Graves’ or control mice [15], washed once with PBS and then incubated for 30 min on ice in the dark with FITC-conjugated goat antimouse IgG (F2772, Sigma Chemical Co., St Louis, MO, USA). After washing once with PBS, the cells (10 000/sample) were analysed by a FACScan flow cytometry (Becton Dickinson Immunocytometry Systems, San Jose, CA, USA) and the CellQuest software program.

Immunization protocol

Female BALB/c mice (∼ 6 weeks old) were injected subcutaneously with 50 µl PBS containing 1 × 106 DCs infected with adenovirus at a MOI of 10 000 particles per cell for 2 h at 37°C under 2000 g centrifugation [17] (day 0). Control mice were injected with PBS alone. The same immunization schedule was performed twice or thrice at 3-week intervals. Some mice were also injected intraperitoneally with a Th2 adjuvant [100 µl alum adjuvant (Pierce Chemical Co., Rockford, IL, USA) and 0·18 µg pertussis toxin (Sigma)][20] on day 0 or a Th1 adjuvant [7·5 µg/g poly (I:C) (Sigma)][21], on 5 consecutive days (day 0 to day 4). All experiments were conducted in accordance with the principles and procedures outlined in the Guideline for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals in Nagasaki University. Mice were kept in a pathogen-free environment.

T4, thyroid stimulating immunoglobulin (TSI) and TSH binding inhibiting immunoglobulin (TBII) measurements

T4, TSI and TBII in mouse sera were determined as described previously [15]. Briefly, T4 was measured with a radioimmunoassay kit (Eiken Chemical, Osaka, Japan). The normal range was defined as the mean ± 3 s.d. of control mice. TSI activities were measured with FRTL5 cells. The cells seeded at 3 × 104 cells/well in a 96-well culture plate were incubated in 50 µl hypotonic HBSS containing 1 mm isobutyl-methylxanthine, 20 mm HEPES, 0·25% BSA and 5 µl serum for 2 h at 37°C. cAMP released into the medium was measured with a radioimmunoassay kit (Yamasa, Tokyo, Japan). A value over 150% of control mice was judged as positive. TBII values were determined with a TRAb kit (RSR Limited, Cardiff, UK). Ten µl of serum was used for each assay. A value over 15% inhibition of control binding was judged as positive.

ELISA for TSHR antibodies

ELISA for detecting mouse IgG antibodies against TSHR was determined as reported previously [22,23] with minor modifications. Briefly, ELISA wells were coated with 100 µl TSHR-289 protein (1 µg/ml) overnight and incubated with mouse sera (1 : 30–300 dilutions). The colour was then developed with antimouse IgG (A3673, Sigma), or subclass-specific antimouse IgGs (IgG1 and IgG2a) (X56 and R19-15, PharMingen, San Diego, CA, USA) conjugated with horseradish peroxidase and orthophenylene diamine as a substrate.

Cytokine secretion from splenocytes

Splenocytes were cultured at 4 × 105 cells per well in a 96-well round-bottomed plate in the presence or absence of TSHR-289 protein (5 µg/ml). Five days later, the concentrations of interferon (IFN)-γ and IL-4 in the medium were determined with ELISA kits (Biosource International, Camarillo, CA, USA). Cytokine production was expressed as pg per ml using standard curves of recombinant murine IL-12 and IL-4.

Thyroid and eye histology

Thyroid tissues and extraocular muscles were removed, fixed with 10% formalin in PBS and embedded in paraffin. Five-µm-thick sections were prepared and stained with H&E.

Results

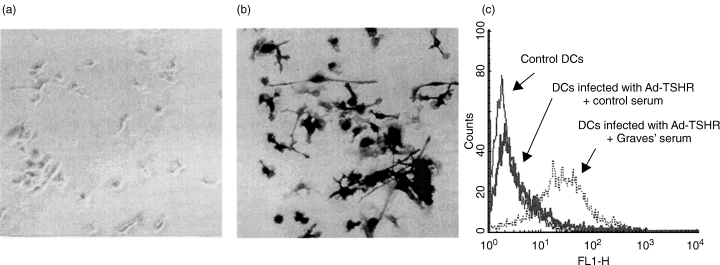

We first evaluated the infectivity of adenovirus for murine bone marrow-derived DCs with AxCALacZ. When DCs were infected with AxCALacZ at a MOI of 10 000 particles per cell under centrifugation at 2000 g at 37°C for 2 h, as reported recently [17], more than 90% of the cells were stained with x-gal (Fig. 1b). Furthermore, flow cytometric analysis revealed that approximately 85% of DCs infected with AdCMVTSHR at a MOI of 10 000 particles per cell in the same condition expressed TSHR (Fig. 1c). Therefore, DCs infected with AdCMVTSHR or AxCALacZ in this condition were used for the subsequent experiments.

Fig. 1.

Transgene expression in DCs infected with adenovirus. (a, b) DCs were left untreated (a) or infected with AxCALacZ at a MOI of 10 000 particles per cell under centrifugation for 2 h at 2000 g at 37°C (b), and stained with x-gal. (c) DCs were left untreated or infected with AdCMVTSHR at a MOI of 10 000 particles per cell under centrifugation for 2 h at 2000 g at 37°C, followed by flow cytometric analysis of TSHR expression with sera from a control mouse and a mouse with Graves’ hyperthyroidism [15].

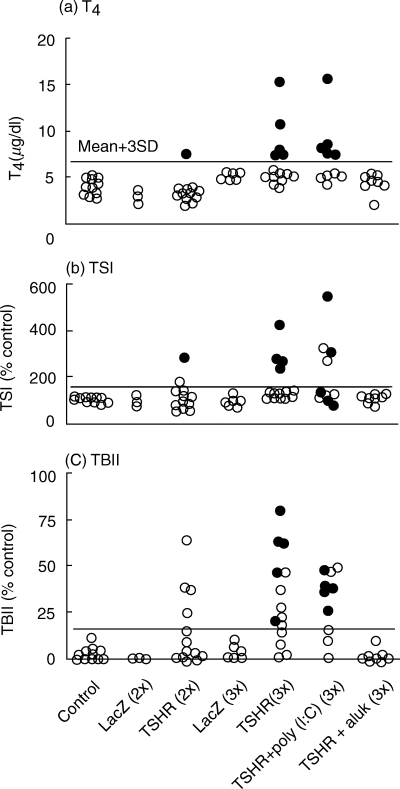

Female BALB/c mice were immunized subcutaneously with DCs infected with either AxCALacZ or AdCMVTSHR (106 cells per injection). Immunization was performed twice or thrice at 3-week intervals. Mice were sacrificed 14 weeks after the first immunization, and serum levels of T4, TSI and TBII were determined (Fig. 2). Serum T4 concentrations in control mice were 4·44 ± 0·78 µg/dL (mean ± s.d.), and the upper limit of serum T4 was defined as 6·78 µg/dL (mean + 3 s.d.). After two injections of DC/AdCMVTSHR, only one of 12 (8%) mice had an elevated T4 level. In contrast, five of 14 (36%) mice immunized thrice with DCs/AdCMVTSHR became hyperthyroid. T4 levels in all mice immunized twice or thrice with AxCALacZ remained in the normal range. TSI activity was observed in most of the hyperthyroid mice, and TBII activity was detectable in all hyperthyroid mice as well as in some euthyroid mice. Correlation coefficients between T4 and TSI, TSI and TBII and T4 and TBII were 0·728, 0·512 and 0·524, respectively.

Fig. 2.

T4, TSI and TBII values in sera from mice immunized with DCs infected with AdCMVTSHR or AxCALacZ alone or in combination with alum or poly (I:C). The normal upper limits are shown by horizontal lines. Data are means of duplicate determinations. Closed circles, hyperthyroid mice; open circles, euthyroid mice. Lane 1, control mice; lane 2, mice immunized 2× with AdCALacZ; lane 3, mice immunized 2× with AdCMVTSHR; lane 4, mice immunized 3× with AdCALacZ; lane 5, mice immunized 3× with AdCMVTSHR; lane 6, mice immunized 3× with AdCMVTSHR and poly (I:C); lane 7, mice immunized 3× with AdCMVTSHR and alum.

To evaluate the role of T-helper subsets in this Graves’ model, mice were immunized with AdCMVTSHR together with either poly (I:C), a Th1-dominant adjuvant, or alum and pertussis toxin, a Th2 adjuvant. Surprisingly, alum/pertussis toxin completely inhibited TSI/TBII formation and disease induction (Fig. 2). In contrast, poly (I:C) administration did not suppress the induction of hyperthyroidism. In this group, the incidence of hyperthyroidism (50%) was not significantly different from the 37% incidence in mice not receiving adjuvant (χ2τest).

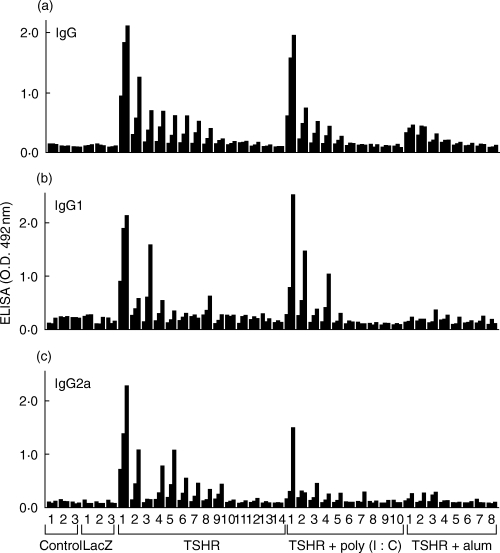

The IgG subclasses of TSHR antibodies were characterized by ELISA. TSHR antibodies of both IgG1 and IgG2a subclasses were detected in mice immunized thrice with DC/AdCMVTSHR (Fig. 3), suggesting that both Th1 and Th2 immune responses are involved in the response to the TSHR in this model. A similar pattern was observed in mice immunized with DC/AdCMVTSHR + poly (I:C). Because only a few sera showed positive signals for both IgG1 and IgG2a even at 1 : 30 dilution, the IgG1/IgG2a ratios were not compared between these two groups. As for TSI and TBII, anti-TSHR IgG titres were very low in the DC/AdCMVTSHR + alum group.

Fig. 3.

IgG subclass distribution of anti-TSHR antibodies in ELISA assays. Total IgG, IgG1 and IgG2a of anti-TSHR antibodies were determined in sera from control mice and those immunized thrice with (i) DCs infected with AxCALacZ, (ii) DCs infected with AdCMVTSHR (DCs/TSHR), (iii) DCs/TSHR and alum or (iv) DCs/TSHR and poly (I:C). Data are means of duplicate determinations obtained with sera from individual mice diluted 1 : 300, 1 : 100 and 1 : 30 (from left to right).

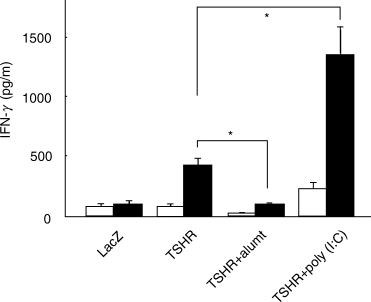

Splenocytes obtained 10 days after two injections with DCs infected with AdCMVTSHR secreted IFN-γ (Fig. 4), not IL-4 (data not shown), in response to TSHR antigen. Co-administration of alum or poly (I:C) significantly suppressed or enhanced, respectively, TSHR-induced IFN-γ secretion. These data clearly demonstrate the deviation of immune response to Th1 and Th2 by poly (I:C) and alum, respectively.

Fig. 4.

IFN-γ production from splenocytes of mice immunized with DCs infected with AdCMVTSHR alone or in combination with alum or poly (I:C). Mice were immunized twice with (i) DCs infected with AxCALacZ, (ii) DCs infected with AdCMVTSHR (DCs/TSHR), (iii) DCs/TSHR and alum or (iv) DCs/TSHR and poly (I:C). Splenocytes were isolated 10 days after the second immunization. IFN-γ in supernatants of splenocytes cultured in the presence or absence of TSHR-289 (5 µg/ml) for 5 days was determined by ELISA. Data are mean ± s.e. (n = 3) and expressed as pg/ml. Open and solid bars, splenocytes cultured in absence or presence of TSHR-289, respectively. *P < 0·05.

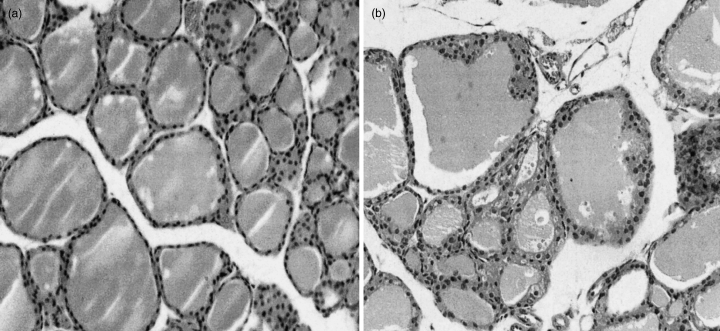

Finally, the histology of the thyroid glands from hyperthyroid mice showed diffuse goitres with hypertrophy and hypercellularity of thyroid epithelial cells, characteristics of Graves’ disease in humans (Fig. 5). These findings were observed consistently in hyperthyroid mice with higher T4, and were less evident and heterogeneous in those with lower T4. No intrathyroidal lymphocytic infiltration was, however, observed. Furthermore, extraocular muscles were intact.

Fig. 5.

Histology (H&E-staining) of the thyroid glands from euthyroid, control (a) and hyperthyroid mice (b). Original magnification, × 200.

Discussion

This study was first designed to investigate the role of DCs, professional APCs, in the induction of Graves’ hyperthyroidism in high responder syngeneic mice. We show here that repeated subcutaneous injection of DCs infected with recombinant adenovirus expressing the TSHR can elicit anti-TSHR antibodies with TSI and TBII activities and induce Graves’-like hyperthyroidism in female BALB/c mice. These data demonstrate that DCs efficiently present the human TSHR, a near ‘self’-antigen, to naive T cells and provide evidence supporting a significant role for DCs in the initiation of autoimmunity leading to Graves’ disease in humans. Disease incidence in this article is, however, slightly lower than that with direct injection of adenovirus expressing the TSHR we have reported recently [15] (36%versus 55%). As mentioned in the Introduction, DCs have been detected in the thyroids of Graves’ and Hashimoto's patients [12–14] as well as in animal models in the initial phase of thyroid autoimmune response [8–11]. Moreover, experimental autoimmune thyroiditis (a model for human Hashimoto's disease) has been reported to be induced in susceptible mice with DCs pulsed with thyroglobulin, one of the autoantigens in Hashimoto's disease [24,25].

It is therefore likely that DCs also play crucial roles in the initiation of autoimmune response in other recently described murine models of Graves’ hyperthyroidism. In two Graves’ models involving intramuscular injection of plasmid DNA [26] or adenovirus expressing the TSHR [15], it is unlikely that muscle cells are involved in antigen presentation because they do not usually express MHC class II or co-stimulatory accessory molecules that are indispensible for T cell stimulation [27]. Consequently, DCs are probable participants in eliciting the immune response to the TSHR by being infected directly with adenovirus, or by taking up antigen expressed in injured (or dead) muscle cells at the injection site [28]. In contrast, the other murine models with injection of fibroblasts or B lymphoblastoid cells expressing syngeneic MHC class II, the TSHR and the co-stimulatory molecule B7-1 [4, 22, 29] implicates non-professional APCs in disease induction. These data together suggest the critical role played by both professional and nonprofessional APCs in the pathogenesis of experimental Graves’ disease. However, it should be noted here that as Graves’ thyroid cells express the TSHR and MHC class II, but not B7 molecules [30], it is possible that these cells induce tolerance rather than immunity against TSHR.

We also addressed the Th1 versus Th2 balance in our new Graves’ model using Th1 and Th2 adjuvants, showing the importance of Th1 immune reaction in disease induction. These data are inconsistent with the general hypothesis that organ-specific autoimmune diseases such as Hashimoto's thyroiditis may be mediated by Th1 cells, whereas humorally mediated autoimmune diseases including Graves’ disease may be mediated by Th2 cells. Indeed, there are numerous controversial data regarding Th1/Th2 paradigm in murine and human Graves’ disease. In animal models, a Th1 adjuvant (complete Freund's adjuvant) has been reported previously to delay and a Th2 adjuvant (alum) to accelerate induction of Graves’ hyperthyroidism in the Shimojo model [31]. However, preferential secretion of IFN-γ (a Th1 cytokine), not IL-4 (a Th2 cytokine), from splenocytes has been demonstrated recently in the same model [22]. In the TSHR DNA vaccination model, although the immune cells infiltrating the thyroid glands are reported to be of Th2 type (B cells, IL-4 producing T cells and mast cells) [26], anti-TSHR monoclonal antibodies established from these mice were all of the Th1 subclass (IgG2a in mice) [19]. TSHR-antigen induced splenocyte secretion of IFN-γ, but not of IL-4, was also observed by the TSHR cDNA vaccination [23]. Histological changes in extraocular muscles were observed only in this model [26] and other study with passive transfer of TSHR-primed T cells [32]. Furthermore, in adenovirus model [15], both IgG1 and IgG2a subclasses of anti-TSHR antibodies and IFN-γ, not IL-4, secretion from splenocytes were documented (unpublished data). Additionally, a stimulating anti-TSHR monoclonal antibody recently established from a hamster immunized with adenovirus expressing the TSHR is of Th1 subclass (IgG2) [33].

In humans, a high incidence of Graves’ disease has been reported after anti-CD52 monoclonal antibody treatment (a Th2-inducer) in patients with multiple sclerosis [34]. However, cytokine expression profiles in Graves’ sera and thyroid glands provide controversial data [35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44]. Human TSHR-specific T cell clones are Th0/Th2 or Th0/Th1 [45,46]. Several other lines of evidence suggest the importance of a Th1 immune response in Graves’ disease. Graves’ disease generally ameliorates during pregnancy (a Th2 dominant state) [47]. Moreover, TSI activities in Graves’ patients are seen in the IgG1 subclass (a Th1 type in human) [48]. These data indicate that it may be an oversimplification to categorize Graves’ disease as a Th2 dominant immune disease. It is worth noting here that a significant role for a Th1 immune response has been reported in other autoantibody-mediated autoimmune diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus, myasthenia gravis and autoimmune haemolytic anaemia [49,50]. Th1 immune responses may therefore play a critical role in the pathogenesis of Graves’ disease.

The contrasting effects of alum (a Th2 adjuvant) in two animal models, namely acceleration of disease in the Shimojo model [31]versus suppression in the present study, suggest that different immunization protocols and/or different mouse strains (different genetic backgrounds) are likely to elicit distinct immune reactions which nevertheless result in the same phenotypic outcome, in this case, hyperthyroidism. Although these murine models may not perfectly mimic human Graves’ disease, one can speculate that the autoimmune reactions to the TSHR in different Graves’ patients may not be identical because humans have different genetic backgrounds and are also exposed to different environmental factors.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that TSHR-expressing DCs efficiently induce TSHR antibodies and Graves’-like hyperthyroidism in female BALB/c mice. Our data also indicate that Graves’ disease may not be a Th2-dominant disease, as considered previously. Graves’ hyperthyroidism in humans may be a heterogeneous disease, involving both Th1 and Th2-type autoimmune responses.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr I. Saito (Tokyo University) for AxCALacZ, Dr J. Miyazaki (Osaka University) for CA promoter, Mrs Y. Iwasaki (Nagasaki University School of Medicine) for technical assistance and Kirin Brewery Co. (Tokyo, Japan) for murine GM-CSF.

References

- 1.Rees Smith B, McLachlan SM, Furmaniak J. Autoantibodies to the thyrotropin receptor. Endocr Rev. 1988;9:106–21. doi: 10.1210/edrv-9-1-106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rapoport B, Chazenbalk GD, Jaume JC, et al. The thyrotropin (TSH) receptor: interaction with TSH and autoantibodies. Endocr Rev. 1998;19:673–716. doi: 10.1210/edrv.19.6.0352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bottazzo GF, Pujol-Borrel R, Hanafusa T, et al. Role of aberrant HLA-DR expression and antigen presentation in induction of endocrine autoimmunity. Lancet. 1983;ii:1115–8. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(83)90629-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shimojo N, Kohno Y, Yamaguchi K, et al. Induction of Graves-like disease in mice by immunization with fibroblasts transfected with the thyrotropin receptor and a class II molecule. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:11074–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.20.11074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mellman I, Steinman RM. Dendritic cells: specialized and regulated antigen processing machines. Cell. 2001;106:255–8. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00449-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dittel BN, Visintin I, Merchant RM, et al. Presentation of the self antigen myelin basic protein by dendritic cells leads to experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol. 1999;163:32–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ludewig B, Odermatt B, Landmann S, et al. Dendritic cells induce autoimmune diabetes and maintain disease via de novo formation of local lymphoid tissue. J Exp Med. 1998;188:1493–501. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.8.1493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Voorbij HAM, Kabel PJ, de Haan M, et al. Dendritic cells and class II MHC expression on thyrocytes during the autoimmune thyroid disease of the BB rat. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1990;55:9–22. doi: 10.1016/0090-1229(90)90065-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mooij P, de Wit HJ, Drexhage HA. An excess of dietary iodine accelerates the development of a thyroid-associated lymphoid tissue in autoimmune prone BB rats. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1993;69:189–98. doi: 10.1006/clin.1993.1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Many M-C, Maniratunga S, Varis I, et al. Two step development of a Hashimoto-like thyroiditis in genetically autoimmune prone non obese diabetic (NOD) mice. Effect of iodine-induced cell necrosis. J Endocrinol. 1995;147:311–20. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1470311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hala K, Malin G, Dietrich H, et al. Analysis of the initiation period of spontaneous autoimmune thyroiditis (SLT) in obese strain (OS) of chicken. J Autoimmun. 1996;9:29–138. doi: 10.1006/jaut.1996.0016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kabel PJ, Voorbij HAM, de Haan M, et al. Intrathyroidal dendritic cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1988;66:199–207. doi: 10.1210/jcem-66-1-199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Quadbeck B, Eckstein AK, Tews S, et al. Maturation of thyroidal dendritic cells in Graves’ disease. Scand J Immunol. 2002;55:612–20. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.2002.01066.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Molne J, Jansson S, Ericson LE, et al. Adherence of RFD-1 positive dendritic cells to the basal surface of thyroid follicular cells in Graves’ disease. Autoimmunity. 1994;17:59–71. doi: 10.3109/08916939409014659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nagayama Y, Kita-Furuyama M, Ando T, et al. A novel murine model of Graves’ hyperthyroidism with intramuscular injection of adenovirus expressing the thyrotropin receptor. J Immunol. 2002;168:2789–94. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.6.2789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Inaba K, Inaba M, Romani N, et al. Generation of large number of dendritic cells from mouse bone marrow cultures supplemented with granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor. J Exp Med. 1992;176:1693–702. doi: 10.1084/jem.176.6.1693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nishimura N, Nishioka Y, Shinohara T, et al. Enhanced efficiency by centrifugal manipulation of adenovirus-mediated interleukin 12 gene transduction into human monocyte-derived dendritic cells. Hum Gene Ther. 2001;12:333–46. doi: 10.1089/10430340150503966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nagayama Y, Nishihara E, Namba H, et al. Targeting the replication of adenovirus to p53-defective thyroid carcinoma with a p53-regulated Cre-loxP system. Cancer Gene Ther. 2001;8:36–44. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Costagliola S, Rodien P, Many M-C, et al. Genetic immunization against the human thyrotropin receptor causes thyroiditis and allows production of monoclonal antibodies recognizing the native receptor. J Immunol. 1998;160:1458–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ulanova M, Tarkowski A, Hahn-Zoric M, et al. The Common vaccine adjuvant aluminum hydroxide up-regulates accessory properties of human monocytes via an interleukin-4-dependent mechanism. Infect Immunol. 2001;69:1151–9. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.2.1151-1159.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Manetti R, Annunziato F, Tomasevic L, et al. Polyionsonic acid:polycytidylic acid promotes T helper type 1-specific immune responses by stimulating macrophage production of interferon-α and interleukin-12. Eur J Immunol. 1995;25:2656–60. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830250938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yan X-M, Guo J, Pichurin P, et al. Cytokines, IgG subclasses and costimuation in a mouse model of thyroid autoimmunity induced by injection of fibroblasts co-expressing MHC class II and thyroid autoantigens. Clin Exp Immunol. 2000;122:170–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2000.01362.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pichurin P, Yan X-M, Farilla L, et al. Naked TSH receptor DNA vaccination: a Th1 T cell response in which interferon-γ production, rather than antibody, dominates the immune response in mice. Endocrinology. 2001;142:3530–6. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.8.8301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Knight SC, Farrant J, Chan J, et al. Induction of autoimmunity with dendritic cells: studies on thyroiditis in mice. Clin Immunol Immunolpathol. 1988;48:277–89. doi: 10.1016/0090-1229(88)90021-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Watanabe H, Inaba M, Adachi Y, et al. Experimental autoimmune thyroiditis induced by thyroglobulin-pulsed dendritic cells. Autoimmunity. 1999;31:273–82. doi: 10.3109/08916939908994073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Costagliola S, Many M-C, Dehef J-F, et al. Genetic immunization of outbred mice with thyrotropin receptor cDNA provides a model of Graves’ disease. J Clin Invest. 2001;105:803–11. doi: 10.1172/JCI7665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Conry RM, Widera G, LoBuglio AF, et al. Selected strategies to augment polynucleotide immunization. Gene Ther. 1996;3:67–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Restifo NP, Ying H, Hwang L, et al. The promise of nucleic acid vaccines. Gene Ther. 2000;7:89–92. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaithamana S, Fan J, Osuga Y, et al. Induction of experimental autoimmune Graves’ disease in BALB/c mice. J Immunol. 1999;163:5157–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Salmaso C, Olive D, Pesce G, et al. Costimulatory molecules and autoimmune thyroid diseases. Autoimmunity. 2002;35:159–67. doi: 10.1080/08916930290013441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kita M, Ahmad L, Marians RC, et al. Regulation and transfer of a murine model of thyrotropin receptor antibody mediated Graves’ disease. Endocrinology. 1999;140:1392–8. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.3.6599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Many M-C, Costagliola S, Detrait M, et al. Development of an animal model of autoimmune thyroid eye disease. J Immunol. 1999;162:4966–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ando T, Latif R, Prisker A, et al. A monoclonal thyroid-stimulating antibody. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:1667–74. doi: 10.1172/JCI16991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Coles A, Wing M, Smith S, et al. Pulsed monoclonal antibody treatment and autoimmune thyroid disease in multiple sclerosis. Lancet. 1999;354:1691–5. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)02429-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mysliwiec J, Kretowski A, Topolska J, et al. Serum Th1 and Th2 profile cytokine level changes in patients with Graves’ ophthalmopathy treated with corticosteroids. Horm Metab Res. 2001;33:739–43. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-19135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kallmann BA, Huther M, Tubes M, et al. Systemic bias of cytokine production toward cell-mediated immune regulation in IDDM and toward humoral immunity in Graves’ disease. Diabetes. 1997;46:237–43. doi: 10.2337/diab.46.2.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tamaru M, Matuura B, Onji M. Increased levels of interleukin-12 in Graves’ disease. Eur J Endocrinol. 1999;141:111–6. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1410111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Al-Humaidi MA. Serum cytokine levels in Graves’ disease. Saudi Med. 2000;7:639–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Roura-Mir C, Catalfamo M, Sospedra M, et al. Single-cell analysis of intrathyroidal lymphocytes shows different cytokine expression in Hashimoto's and Graves’ disease. Eur J Endocrinol. 1997;27:3290–302. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830271228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Heuer M, Aust G, Ode-Hakim S, et al. Different cytokine mRNA profiles in Graves’ disease, Hashimoto's thyroiditis, and nonautoimmune thyroid disorders determined by quantitative reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) Thyroid. 1996;6:97–106. doi: 10.1089/thy.1996.6.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Paschke R, Schuppert F, Taton M, et al. Intrathyroidal cytokine gene expression profiles in autoimmune thyroiditis. J Endocrinol. 1994;141:309–15. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1410309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Watson PF, Pickerill AP, Davies R, et al. Analysis of cytokine gene expression in Graves’ disease and multinodular goiter. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1994;79:355–60. doi: 10.1210/jcem.79.2.8045947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ajjan RA, Watson PF, McIntosh RS, et al. Intrathyroidal cytokine gene expression in Hashimoto's thyroiditis. Clin Exp Immunol. 1996;105:523–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1996.d01-784.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.De La Vega JR, Vilaplana JC, Biro A, et al. IL-10 expression in thyroid glands: protective or harmful role against thyroid autoimmunity? Clin Exp Immunol. 1998;113:126–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1998.00628.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mullins RJ, Cohen SBA, Webb LMC, et al. Identification of thyroid stimulating hormone receptor-specific T cells in Graves’ disease thyroid using autoantigen-transfected Epstein–Barr virus-transformed B cell lines. J Clin Invest. 1995;96:30–7. doi: 10.1172/JCI118034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fisfalen ME, Palmer EM, Van Seventer GA, et al. Thyrotropin-receptor and thyroid peroxidase-specific T cell clones and their cytokine profile in autoimmune thyroid disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82:3655–63. doi: 10.1210/jcem.82.11.4336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Davies TF. The thyroid immunology of the postpartum period. Thyroid. 1999;9:675–84. doi: 10.1089/thy.1999.9.675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Weetman AP, Yateman ME, Ealey PA, et al. Thyroid-stimulating antibody activity between different immunoglobulin G subclasses. J Clin Invest. 1990;86:723–7. doi: 10.1172/JCI114768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Theofilopoulos AN, Lawson BR. Tumor necrosis factor and other cytokines in murine lupus. Ann Rheum Dis. 1999;58:149–5. doi: 10.1136/ard.58.2008.i49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Elson C, Baker RN. Helper T cells in antibody-mediated, organ-specific autoimmunity. Curr Opin Immunol. 2000;12:664–9. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(00)00160-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]