Abstract

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection leads to a profound T cell dysfunction well before the clinical onset of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). We have been accumulating evidence that one of the mechanisms responsible for this T cell deficiency may be the dysregulation of signal transduction via the interleukin (IL)-2/IL-2 receptor (R) complex. In CD4 T cells, we have observed previously that viral envelope (env) glycoproteins induce IL-2 unresponsiveness and the down-regulation of the three chains making up the IL-2R (α, β, γ) in vitro. We have now established further that this disruption of the IL-2/IL-2R system manifests itself in defective signal propagation via the Janus kinase (Jak)/signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) pathway in response to IL-2. The treatment of CD4 T cells with HIV env or surface ligation of CD4 with anti-CD4 monoclonal antibodies inhibited the IL-2-induced activation of Jak-1 and Jak-3, as well as their targets, STAT5a and STAT5b. This Jak/STAT deficiency may contribute to the crippling of CD4 T cell responses to a cytokine central to the immune response by HIV.

Keywords: CD4 T lymphocytes, HIV env, IL-2, Jak, STAT

Introduction

Despite intense scrutiny, the profound dysfunction of CD4 T lymphocytes caused by the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and characterized in part by the progressive failure in their mitogenic responses remains incompletely understood. However, both direct and indirect pathogenic effects of virus infection have been implicated [1]. A general deficiency within the IL-2 system has long been recognized in HIV infection and includes a poor reactivity of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) from AIDS patients to this cytokine [2–4]. Therefore, considering its critical role in T cell growth and differentiation [5], this fact may play an important role in the virus-induced T cell immunosuppression described.

In vitro incubation with HIV envelope glycoproteins (gp120/gp41), much like the cross-linking of CD4 with certain anti-CD4 monoclonal antibodies, exerts immunosuppressive effects on the proliferation of CD4 T cells to TCR stimulation [6]. We were the first to extend this unresponsiveness to the cytokine IL-2 [7]. IL-2 unresponsiveness in our model using purified human CD4 T lymphocytes was correlated with a reduction in the expression of not only the IL-2Rα chain, which is associated mainly with modulating affinity for IL-2, but of the signal transducing components of the IL-2R, the IL-2Rβ and IL-2Rγ chains.

The Janus kinase (Jak)/signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) pathway, represents a major signal transduction pathway involved in cytokine responses [8] and therefore is an attractive target for HIV in its capacity to cause T cell dysfunction. Interaction of IL-2 with its receptor triggers within minutes the Jak/STAT signal transduction cascade [5]. This involves the phosphorylation of Jak-1 and Jak-3, kinases that are constitutively associated with the β and γ receptor subunits, respectively, and IL-2R phosphorylation. This is followed by STAT5 recruitment to the phosphorylated receptor complex, STAT5 phosphorylation, dimerization, nuclear translocation and transactivation of target genes. Human STAT5 is encoded by two closely linked genes, STAT5a and STAT5b, which exhibit 91% identity at the amino acid level. Both proteins are phosphorylated in response to IL-2 and play a critical role in CD4 T cell proliferation induced by this cytokine.

Information has accumulated concerning HIV-induced defects in T cell signalling [9–11]. However, neither the impact of the IL-2R dysregulation that we observed nor the molecular targets of HIV in the IL-2-induced Jak/STAT signalling pathway are known. Therefore, we investigated the integrity of this pathway in CD4 T cells subjected to the immunosuppressive effects of HIV env or anti-CD4 monoclonal antibody (MoAb) in vitro. We demonstrated that the main players recruited by IL-2 in this pathway, namely Jak-1, Jak-3, STAT5a and STAT5b, are attenuated and may thus contribute to defective CD4 T cell proliferation in response to this cytokine.

Materials and methods

HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein

The recombinant HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein preparation (env) used in all experiments was obtained from Pasteur-Merieux Connaught (Marcy l’Etoile, France) in purified form. The gp120 and gp41 portions of the preparation were derived from the MN and LAI strains of HIV-1. At the concentrations used, env proteins were able to saturate CD4 on the cell surface as determined by the elimination of anti-CD4-FITC antibodies (MT310, Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) binding by flow cytometry (data not shown).

CD4 T cell purification and culture

Venous blood from healthy volunteers was obtained from the Centre de Transfusion Sanguine-Lecourbe (Paris, France). CD4 T lymphocytes were prepared by negative selection from PBMC, essentially as described elsewhere [12]. The CD4 T cells obtained in this fashion were>90% pure, as determined by flow cytometry using anti-CD4-FITC and anti-CD3-PE (UCHT1, Dako) antibodies.

Purified CD4 T cells were treated with either anti-CD4 MoAb 13B8·2 (Immunotech, Marseille, France) or Leu3a (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA, USA) at 1 µg/ml, HIV-1 env at 5 µg/ml or negative controls [mouse IgG1 MoAb (Coulter; Miami, FL, USA) or PBS] for 1–2 h at 37°C. Next, the cells were stimulated with suboptimal amounts of anti-CD3 antibodies (UCHT1, Dako) for 2 days at a concentration of 106 cells/ml in RPMI-1640 cell culture medium containing 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS). For this, anti-CD3 antibody (62·5 ng/ml) was immobilized on 24-well flat-bottom plates (Corning Inc., Corning, NY, USA) coated with goat-antimouse IgG antibody (30 µg/ml, Immunotech). After 2 days, cells were collected, washed with serum free RPMI-1640 and stimulated (4 min at 37°C) with IL-2 (Chiron-Europe, Amsterdam, the Netherlands) at 10 nm in serum free RPMI-1640 and 107 cells/ml. IL-2-stimulated cells were subsequently lysed for immunoprecipitation and Western blot analysis.

Immunoprecipitation and Western blotting

Cell lysis and protein extraction was carried out in a lysis buffer containing 1% Triton-X100 detergent, 10 mm Tris, 10 µg/ml PMSF, 1 mm Na orthovanadate, 50 mm NaF and 10 µg/ml leupeptin for 20 min on ice. Equal concentrations of protein extracts were immunoprecipitated with rabbit antibody directed against Jak-1, Jak-3, STAT5a from Santa Cruz (Santa Cruz, CA, USA), and STAT5b (Pharmingen, San Diego, CA, USA) for 1·5 h at 4°C followed by an equivalent incubation with Pansorbin (Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA, USA). Immunoprecipitates were heat denatured (7 min, 100°C) in a buffer containing 62·5 mm Tris, 5% 2-ME, 10% glycerol, 2% SDS and bromophenol blue, resolved on 8% SDS-PAGE gels and transferred to PVDF membranes (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA). The membranes were probed first with mouse antiphosphotyrosine MoAb 4G10 (Upstate Biotechnologies, Lake Placid, NY, USA) followed by a horseradish peroxidase (HRP) coupled antimouse IgG (Amersham, Buckinghamshire, UK) and expression revealed using ECL Western blotting detection reagents (Amersham). Membranes were then stripped in a buffer containing 2% SDS, 62·5 mm Tris, and 100 mm 2-ME and re-probed with an antibody directed against the appropriate Jak (Jak1 from Transduction Laboratories, Lexington, KY, USA; or Jak3) or STAT followed by a species specific HRP coupled antibody (antimouse IgG-HRP from Amersham or antirabbit IgG-HRP from PARIS, Compiègne, France) and ECL detection. The intensity of protein tyrosine-phosphorylation and protein expression levels were measured by densitometric scanning of the specific bands using an AGFA Snapscan e50™ and NIH image analysis software v1·62. The percentage inhibition of Jak/STAT phosphorylation relative to controls was calculated as follows:

The activation ratio refers to the signal ratio of phosphorylated versus total protein in response to IL-2 and the basal ratio is that obtained in the absence of IL-2.

Results and discussion

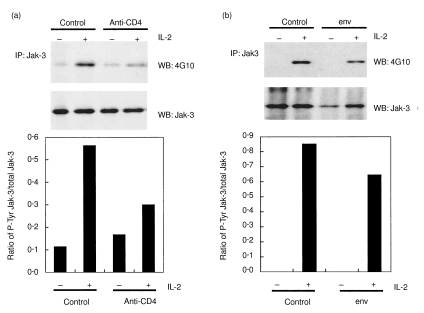

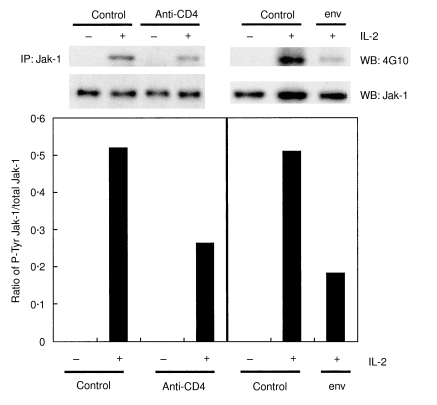

We studied whether the CD4 T cell unresponsiveness induced by the pretreatment of CD4 T cells with HIV env or anti-CD4 MoAb impacted on IL-2-induced Jak-3 activation. Following pretreatment (1–2 h at 37°C) with HIV env or anti-CD4 MoAb CD4 T cells were stimulated at suboptimal amounts of anti-CD3 for 2 days and then stimulated for 4 min with IL-2. It should be noted that we defined suboptimal anti-CD3 stimulation conditions to use such that the induction of Jak/STAT phosphorylation could be observed specifically in response to exogenously added IL-2. We often observed low basal levels of Jak/STAT phosphorylation in the absence of exogenous IL-2 following anti-CD3 stimulation. This resulted probably from low levels of endogenous cytokine(s) production in response to anti-CD3 stimulation and/or direct activation via the TCR. Jak-3 was immunoprecipitated from the protein extracts of stimulated cells and resolved on SDS-PAGE gels. Western blotting with antiphosphotyrosine (4G10) MoAb followed by anti-Jak-3 antibody revealed that both anti-CD4 MoAb and HIV env attenuated Jak-3 phosphorylation in response to IL-2 relative to control treated cells, although a less marked effect was observed for env (Fig. 1a,b). Densitometric analysis comparing phosphorylated versus total Jak-3 expression levels showed an inhibition of 65% and 24% by anti-CD4 and env, respectively. The fact that Jak-1 is activated in response to IL-2 and has been identified as a potential target of Jak-3 [13] prompted us to investigate its phosphorylation status in similarly prepared cell extracts. Figure 2 shows that Jak-1 phosphorylation in response to IL-2 is indeed inhibited by anti-CD4 MoAb and HIV env at a level of 49% and 64%, respectively.

Fig. 1.

Inhibition of Jak-3 phosphorylation by anti-CD4 MoAb (a) and HIV env (b). Purified CD4 T cells were incubated with HIV env (5 µg/ml), anti-CD4 MoAb 13B8·2 (1 µg/ml) or controls then cultured with suboptimal anti-CD3 antibody concentrations for 2 days and finally stimulated in the presence (+) or absence (–) of IL-2 for 4 min, as described in Materials and methods. Protein extracts were prepared and Jak-3 was immunoprecipitated (IP) with anti-Jak-3 antibody and analysed by Western blotting (WB) using antiphosphotyrosine (P-Tyr) MoAb (4G10) followed by stripping and revelation with anti-Jak-3 antibody (Jak-3). Densitometric analysis of the signals obtained was plotted as the ratio of phosphorylated versus total Jak-3.

Fig. 2.

Jak-1 phosphorylation is inhibited by anti-CD4 MoAb and HIV env in CD4 T cells. Cells were treated as indicated in the legend to Fig. 1. Jak-1 activation status in cells treated with (+) or without (–) IL-2 was evaluated by immunoprecipitation (IP) with anti-Jak-1 antibody and Western blotting (WB) using anti-P-Tyr MoAb (4G10) and anti-Jak-1 antibody as described in Materials and methods. Densitometry results are shown as in Fig. 1.

Our results are different from those reported by Selliah et al. [14]. They demonstrated that treatment of CD8-depleted PBMC with HIV gp120 reduced the amount of Jak-3 expression and phosphorylation obtained in response to TCR stimulation. However, under their experimental conditions Jak-1 was unaffected. These differences can be explained by the fact that, unlike in the work by Selliah, we used highly purified CD4 T cells (>90%) and measured Jak-1 and Jak-3 phosphorylation that was induced specifically by IL-2.

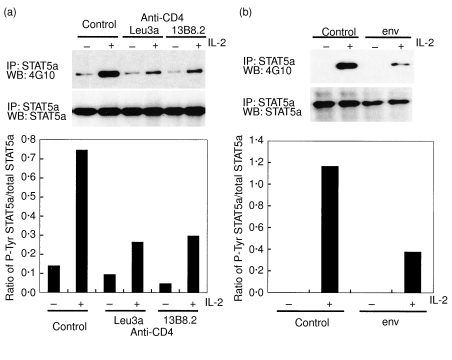

Subsequently, we explored whether the inhibition of Jak-3 and Jak-1 phosphorylation altered events downstream, namely STAT5 phosphorylation and activation. Figure 3 shows clearly that STAT5a phosphorylation in response to IL-2 is inhibited by treating cells with two different anti-CD4 MoAb, 13B8·2 and Leu3a (Fig. 3a) as well as with HIV env (Fig. 3b). Densitometry revealed a percentage inhibition that amounted to 72%, 59% and 68% for Leu3a, 13B8·2 and env, respectively. Because STAT5b activation is also induced by IL-2 [15], its phosphorylation status was investigated (Fig. 4). The level of STAT5b phosphorylation in response to IL-2 stimulation was reduced by 42% and 61% in CD4 T cells treated with anti-CD4 MoAb and HIV env, respectively. Curiously, we observed that although Tyr-phosphorylation of STAT5b was reduced overall, the protein nevertheless underwent a mobility shift (appearance of doublet) in response to IL-2. Previous studies have documented that STAT5b undergoes an SDS-PAGE mobility shift in response to activating signals, which may be the result of Ser phosphorylation [16]. This was not pursued further as the significance of Ser phosphorylation in both STAT5a or STAT5b is not understood.

Fig. 3.

Anti-CD4 MoAb (Leu3a and 13B8·2) (a) and HIV env (b) inhibit STAT5a phosphorylation in response to IL-2. CD4 T cells were subjected to a treatment identical to that described in the legend to Fig. 1. Immunoprecipitation (IP) with anti-STAT5a antibody and Western blotting (WB) experiments using anti-P-Tyr MoAb (4G10) followed by anti-STAT5a antibody were carried out as in Materials and methods. Densitometric analysis is presented as in Fig. 1.

Fig. 4.

Tyr-phosphorylation of STAT5b but not its SDS-PAGE electrophoretic mobility shift in response to IL-2 is inhibited by anti-CD4 MoAb and HIV env glycoproteins. Purified CD4 T cells were treated as described in Fig. 1. STAT5b Tyr-phosphorylation status was evaluated by immunoprecipitation (IP) with anti-STAT5b antibody followed by Western blotting (WB) using anti-P-Tyr MoAb (4G10) and anti-STAT5b antibody, as described in Materials and methods. Densitometric analysis of STAT5b phosphorylation is presented as in Fig. 1.

The inhibition of IL-2-induced STAT5 phosphorylation that we have observed may further uncover an important mechanism by which inappropriate ligation of the CD4 molecule causes CD4 T cell immunosuppression. Goebel et al. [17] have suggested previously that cross-linking of CD4 on PHA-activated CD4 T cells using an anti-CD4 MoAb (16H5) inhibited STAT5 activation in response to IL-2, although no distinction between STAT5a and STAT5b proteins was attempted. Here, we confirm and extend these results to the inhibition of STAT5a and STAT5b phosphorylation. More interestingly, we obtained similar results when anti-CD4 MoAb or HIV-env were used to treat highly purified CD4 T cells. Thus, the reduction of STAT5a and STAT5b protein activation may explain the attenuation of CD4 T cell proliferation in response to IL-2 that we have observed previously after treatment with gp120 [7]. This follows logically from the results that demonstrate that deficiency in either STAT5a and/or STAT5b resulted in a reduced capacity to proliferate in response to this cytokine [18,19].

The physiological relevance of our results is reinforced by the fact that gp120 has been detected in the serum of HIV positive patients [20]. Furthermore, it does appear that Jak/STAT pathway alterations exist after HIV infection in vitro and in seropositive patients. It has been shown that in vitro HIV infection of CD8-depleted PHA blasts reduced both Jak-1 and Jak-3 activation as well as Jak-3 but not Jak-1 expression levels [21]. Interestingly, this inhibition was virus strain-specific and may be associated with the ability of the viruses tested to induce apoptosis. In addition, in vitro HIV infection resulted in the inhibition of STAT5 expression and phosphorylation. We did not study whether the inhibition of IL-2-induced Jak/STAT signalling was related to the strain of HIV from which the env glycoproteins were derived nor whether there were any differences between M-tropic and T-tropic strains, both of which bind CD4. However, if we consider that the inhibition probably occurred via HIV env ligation of CD4, then it would be expected that any strain-related differences would be a function of their CD4 binding capacity. Pericle et al. [22] have demonstrated that peripheral CD3+ T cells from HIV+ patients have a reduced STAT5a, STAT5b and STAT1α expression, although their activation was not addressed. Our study did not show any evidence of reduced STAT5a or STAT5b expression after treatment of CD4 lymphocytes with gp120 or anti-CD4 MoAb. Bovolenta et al. [23] showed that STAT1 and a truncated, potentially dominant negative STAT5 isoform were constitutively activated in PBMC from HIV-infected individuals. However, this study does not address the capacity of IL-2 or other cytokines to activate the Jak/STAT pathway in the different PBMC subsets.

Altogether, our results clearly show that the Jak/STAT pathway initiated by the cytokine IL-2, comprised of Jak-1, Jak-3, STAT5a and STAT5b, is strongly inhibited by HIV env glycoproteins and by prior ligation of CD4 with anti-CD4 MoAb. These findings provide a potential mechanism to explain our previous observations of IL-2/IL-2R regulatory dysfunction within the CD4 T cell compartment that are caused by HIV both in vitro and ex vivo [7,24]. Although this remains the subject of future studies, it is appropriate to speculate on how the ligation of the CD4 molecule may lead to the inhibition of IL-2-dependent Jak/STAT signalling. Mechanisms demonstrated to be important in gp120-induced attenuation of TCR signalling may be paralleled in the IL-2 system. Goldman et al. [25] have presented a model for gp120-induced TCR desensitization in the Jurkat T cell line, which involves the sequestration of the src family kinase p56lck into the cytoskeleton resulting in the reduced availability of this kinase for subsequent TCR-mediated signalling. Considering that this kinase also associates with the IL-2Rβ chain and is important in IL-2-dependent signalling [26], a mechanism involving the sequestration of this kinase or the analogous perturbation of other signalling molecules associated with the IL-2R complex may be important. Whatever the mechanisms involved, IL-2 immunotherapy is able to increase the CD4 counts in HIV seropositive patients, however, the target of exogenously administrated IL-2 is not clear at present. We have shown previously [27,28] that the CD4 T cells in a subset of patients whose CD4 counts fail to increase rapidly in response to highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) express a dysfunctional IL-2R at the level of IL-2-dependent cell cycle entry. Upon in vivo administration of IL-2 to these patients their CD4 counts do increase, as does the reactivity of their CD4 T cells to IL-2. This suggested that the direct target cells of exogenously administered IL-2 may not be the peripheral blood CD4 lymphocytes. However, further investigation is required, particularly in light of the results from recent work by Sereti et al. [29] that describes a preferential expansion of a novel subset of CD4+/CD25+ T cells in HIV+ patients treated with IL-2 in vivo. They suggest that these cells may arise from Ag-independent exogenous IL-2-induced expansion.

Although via different routes, the dysregulation of the IL-2 system is emerging to be an immunosuppressive mechanism exploited not only by HIV but also by other viral pathogens. Measles virus fusion and haemagglutinin proteins have been recently shown to target the Akt kinase in order to induce IL-2 unresponsiveness in T cells [30]. CMV infection of dendritic cells was shown to attenuate their ability to produce IL-2 when exposed to bacterial products and rendered them unable to effectively prime naive T cell responses [31]. Therefore, in order to further our understanding of the immunopathological mechanisms involved, it is important to conduct studies such as these, aimed at dissecting the molecular mechanisms exploited by HIV and other viruses to cause immunosuppression and disease in the host.

Acknowledgments

M.K. was a recipient of a postdoctoral fellowship from the Canadian Institute for Health Research. V.P. is supported by a studentship from the Agence Nationale de Recherches sur le SIDA (ANRS). This work was supported by grants to J.T. from the ANRS. The authors also wish to thank Dr Ralf Altmeyer for his help in obtaining a source for HIV envelope glycoproteins.

References

- 1.McCune J. M. The dynamics of CD4+ T-cell depletion in HIV disease. Nature. 2001;410:974–9. doi: 10.1038/35073648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Poli G. Cytokines and chemokines in HIV infection. In: Pantaleo G, Walker BD, editors. Retroviral immunology. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 2001. pp. 53–78. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hauser GJ, Bino T, Rosenberg H, Zakuth V, Geller E, Spirer Z. Interleukin-2 production and response to exogenous interleukin-2 in a patient with the acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) Clin Exp Immunol. 1984;56:14–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chopra RK, Raj NB, Scally JP, et al. Relationship between IL-2 receptor expression and proliferative responses in lymphocytes from HIV-1 seropositive homosexual men. Clin Exp Immunol. 1993;91:18–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1993.tb03347.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thèze J, Alzari PM, Bertoglio J. Interleukin 2 and its receptors: recent advances and new immunological functions. Immunol Today. 1996;17:481–6. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(96)10057-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oyaizu N, Chirmule N, Kalyanaraman VS, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope glycoprotein gp120 produces immune defects in CD4+ T lymphocytes by inhibiting interleukin 2 mRNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:2379–83. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.6.2379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bani L, David D, Fevrier M, et al. Interleukin-2 receptor beta and gamma chain dysregulation during the inhibition of CD4 T cell activation by human immunodeficiency virus-1 gp120. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:2188–94. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830270911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leonard WJ, O'Shea JJ. Jaks and STATs: biological implications. Annu Rev Immunol. 1998;16:293–322. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.16.1.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cayota A, Vuillier F, Siciliano J, Dighiero G. Defective protein tyrosine phosphorylation and altered levels of p59fyn and p56lck in CD4 T cells from HIV-1 infected patients. Int Immunol. 1994;6:611–21. doi: 10.1093/intimm/6.4.611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tamma SM, Chirmule N, McCloskey TW, Oyaizu N, Kalyanaraman VS, Pahwa S. Signals transduced through the CD4 molecule interfere with TCR/CD3-mediated ras activation leading to T cell anergy/apoptosis. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1997;85:195–201. doi: 10.1006/clin.1997.4424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jabado N, Le Deist F, Fisher A, Hivroz C. Interaction of HIV gp120 and anti-CD4 antibodies with the CD4 molecule on human CD4+ T cells inhibits the binding activity of NF-AT, NF-kappa B and AP-1, three nuclear factors regulating interleukin-2 gene enhancer activity. Eur J Immunol. 1994;24:2646–52. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830241112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bani L, David D, Moreau JL, et al. Expression of the IL-2 receptor gamma subunit in resting human CD4 T lymphocytes: mRNA is constitutively transcribed and the protein stored as an intracellular component. Int Immunol. 1997;9:573–80. doi: 10.1093/intimm/9.4.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhou YJ, Magnuson KS, Cheng TP, et al. Hierarchy of protein tyrosine kinases in interleukin-2 (IL-2) signaling: activation of syk depends on Jak3; however, neither Syk nor Lck is required for IL-2-mediated STAT activation. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:4371–80. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.12.4371-4380.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Selliah N, Finkel TH. Cutting edge. JAK3 activation and rescue of T cells from HIV gp120-induced unresponsiveness. J Immunol. 1998;160:5697–701. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin JX, Leonard WJ. The role of Stat5a and Stat5b in signaling by IL-2 family cytokines. Oncogene. 2000;19:2566–76. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yamashita H, Xu J, Erwin RA, Farrar WL, Kirken RA, Rui H. Differential control of the phosphorylation state of proline-juxtaposed serine residues Ser725 of Stat5a and Ser730 of Stat5b in prolactin-sensitive cells. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:30218–24. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.46.30218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goebel J, Forrest KJ, Mikovits J, Emmrich F, Volk HD, Lowry RP. STAT5 pathway. target of anti-CD4 antibody in attenuation of IL-2 receptor signaling. Transplantation. 2001;71:792–6. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200103270-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nakajima H, Liu XW, Wynshaw-Boris A, et al. An indirect effect of Stat5a in IL-2-induced proliferation: a critical role for Stat5a in IL-2-mediated IL-2 receptor alpha chain induction. Immunity. 1997;7:691–701. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80389-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Imada K, Bloom ET, Nakajima H, et al. Stat5b is essential for natural killer cell-mediated proliferation and cytolytic activity. J Exp Med. 1998;188:2067–74. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.11.2067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oh SK, Cruikshank WW, Raina J, et al. Identification of HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein in the serum of AIDS and ARC patients. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1992;5:251–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Selliah N, Finkel TH. HIV-1 NL4-3, but not IIIB, inhibits JAK3/STAT5 activation in CD4 (+) T cells. Virology. 2001;286:412–21. doi: 10.1006/viro.2001.0994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pericle F, Pinto LA, Hicks S, et al. HIV-1 infection induces a selective reduction in STAT5 protein expression. J Immunol. 1998;160:28–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bovolenta C, Camorali L, Lorini AL, et al. Constitutive activation of STATs upon in vivo human immunodeficiency virus infection. Blood. 1999;94:4202–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.David D, Bani L, Moreau JL, et al. Regulatory dysfunction of the interleukin-2 receptor during HIV infection and the impact of triple combination therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:11348–53. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.19.11348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goldman F, Crabtree J, Hollenback C, Koretzky G. Sequestration of p56lck by gp120, a model for TCR desensitization. J Immunol. 1997;158:2017–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gesbert F, Delespine-Carmagnat M, Bertoglio J. Recent advances in the understanding of interleukin-2 signal transduction. J Clin Immunol. 1998;18:307–20. doi: 10.1023/a:1023223614407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.David D, Nait-Ighil L, Dupont B, Maral J, Gachot B, Theze J. Rapid effect of interleukin-2 therapy in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients whose CD4 cell counts increase only slightly in response to combined antiretroviral treatment. J Infect Dis. 2001;183:730–5. doi: 10.1086/318824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.David D, Keller H, Nait-Ighil L, et al. Involvement of Bcl-2 and IL-2R in HIV-positive patients whose CD4 cell counts fail to increase rapidly with highly active antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2002;16:1093–101. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200205240-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sereti I, Martinez-Wilson H, Metcalf JA, et al. Long-term effects of intermittent interleukin 2 therapy in patients with HIV infection: characterization of a novel subset of CD4 (+) /CD25 (+) T cells. Blood. 2002;100:2159–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Avota E, Avots A, Niewiesk S, et al. Disruption of Akt kinase activation is important for immunosuppression induced by measles virus. Nat Med. 2001;7:725–31. doi: 10.1038/89106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Andrews DM, Andoniou CE, Granucci F, Ricciardi-Castagnoli P, Degli-Esposti MA. Infection of dendritic cells by murine cytomegalovirus induces functional paralysis. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:1077–84. doi: 10.1038/ni724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]