Abstract

Cutaneous tolerance to antigens may be induced in mice through application of antigen during the first few days following birth. The mechanism governing this neonatally induced tolerance remains uncertain. We employed a contact hypersensitivity model to analyse dendritic cell (DC) function and the expression of classical and non-classical lymphocyte populations within the neonate. Examination of draining lymph node DC after antigenic challenge of the skin revealed these DC to be significantly deficient in their ability to stimulate antigen-specific T cell proliferation. Co-stimulatory molecule (CD40, CD80 and CD86) expression of these cells was deficient in comparison to adult DC, and functional tests revealed these cells to possess a critical absence of CD40 signalling. A numerical analysis of classical and non-classical lymphocyte expression demonstrated that while the neonatal spleen is devoid of T cells, the lymph nodes have a normal repertoire of T, B, γδ and CD4+CD25+ lymphocytes but an increased expression of natural killer (NK) cells. This study indicates that functionally deficient DC are likely contributors to neonatally induced cutaneous tolerance.

Keywords: contact sensitivity, co-stimulatory molecule, dendritic cells, neonatal tolerance, NK, CD40

INTRODUCTION

As a consequence of the seminal work of Medawar in the 1950s [1] and several subsequent studies [2–4], it has generally been accepted that neonatal animals are uniquely susceptible to tolerance induction. It was thought that the neonate's immune system was qualitatively different to their adult counterparts, and that this difference was crucial to an animal's ability to establish tolerance to its own tissues. This phenomenon has been manipulated in numerous attempts to prevent the onset of disease in experimental systems of autoimmunity, such as diabetes [5] and experimental allergic encephalomyelitis [6,7].

The precise cause of neonatally induced T cell unresponsiveness has not yet been clarified fully, although several studies have nominated such mechanisms as clonal deletion or anergy of antigen-specific cells [6,8] or antigen-specific suppressor cell generation [9]. However, the long-held notion that neonates are immune privileged has recently been challenged by evidence of at least partial neonatal immune competence. Studies demonstrating skewing of the neonatal immune response towards the Th2 phenotype [10] and the pivotal role of antigen-presenting cells (APC) involved during this period [11] have forced a revision of the classical theories previously devised to explain neonatal tolerance. Subsequent proposals regarding the mechanism underlying neonatal tolerance may be summarized within two general areas: those that rely on the neonatal immune system being qualitatively different to that of the adult, and those that argue for a quantitative difference only. The latter theories note that the number of T cells present within the neonatal spleen, which are approximately 1000 times lower than in adults, is suggested to be the critical component of neonatal non-responsiveness [12]. Evidence supporting a qualitative difference within neonates is building but is divergent, as some groups have demonstrated a CD40L deficiency within T cells [13,14], while others maintain that neonatal T cells show normal CD40L up-regulation are still deficient in interferon (IFN)-γ production [15], Th1 lineage development and cytotoxic function [16–18].

We suggest that multiple mechanisms are responsible for neonatal tolerance, which is likely to be caused partly by deficiencies within the capacity of resident APC to stimulate normal T cell responses. Reports of neonatal Ia-bearing adherent cell deficiencies were reported first in 1980 [19], yet characterization of neonatal APC is far from complete. Utilizing the contact hypersensitivity (CHS) model, we investigated the T cell stimulatory and co-stimulatory capacity of the murine epidermal dendritic cell (DC) representative, the Langerhans’ cell (LC), during the neonatal period. To examine the role of the major secondary lymphoid organs involved in CHS play during this critical period, we also conducted a numerical and phenotypical analysis of neonatal mouse spleen and lymph node (LN) cell populations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

BALB/c (H-2d) and FVB/N (H-2q) mice were obtained from the University of Tasmania Central Animal House and were used with the permission of the University of Tasmania Ethics Committee (Animal Experimentation), permit number A5629.

Antigens and vehicles

Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) and dinitrofluorobenzene (DNFB) were from Sigma (St Louis, MO, USA), and the vehicle for both antigens was 4 : 1 acetone: Di-n-butyl phthalate.

Treatment of mice

The dorsal trunk was shaved with electric animal clippers (Oster Corporation, model number A5-00, Milwaukee, WI, USA) and the mice were treated on their dorsal surface with applications of 150 µl of a 1·5% solution of either FITC or DNFB. Eighteen h later the draining lymph nodes and spleen were removed and cell suspensions prepared as detailed below. FITC immune mice were treated on their shaved dorsal skin with 150 µl of a 1·5% solution of FITC, followed 7 days later by another application of FITC. The spleen was removed 5 days later and T cells prepared as described below.

Cell suspensions

Adult mice were killed by CO2 asphyxiation, while neonatal mice were decapitated following cold anaesthesia. The lymph nodes (brachial, axillary and inguinal) and spleen were removed, aggregated as adult and neonatal preparations in a sterile Petri dish containing incomplete Dulbecco's minimum essential medium (DMEM) (CSL Limited, Victoria, Australia, no additions) with type II collagenase (1 mg/ml; Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany), chopped finely and incubated at 37°C for 20 min. The digested material was then disaggregated by gentle pipetting and the cell suspension allowed to settle on ice for 5 min to allow removal of tissue remnants and clumps. The supernatant was then washed once and resuspended in either DMEM-10FCS (DMEM; supplemented with 2 mm glutamine, CSL Limited; 5 × 10−5m 2-mercaptoethanol, Sigma; 150 µg/ml gentamicin, David Bull Laboratories, Melbourne, Australia; and 10% fetal calf serum, CSL Limited) for cell culture or PBS–BSA–Azide (2% BSA, CSL Limited; 0·1% sodium azide, Sigma) for antibody staining.

Flow cytometry

For surface stains, cell suspensions were prepared in PBS/2%BSA/0·1% azide and treated with FcBlock (BD Pharmingen) to block Fc receptors prior to using the following fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated, phycoerythrin-conjugated or biotinylated antibodies (all supplied by BD Pharmingen): CD3e (145–2C11), CD4 (L3T4), CD8a (Ly-2), H2-Dd (34-2-12), I-A/I-E (M5/114·15·2), CD80/B7-1 (16–10A1), CD86/B7-2 (GL1), CD40 (3/23), Pan-NK (DX-5), γδ (GL3), CD25 (3C7), CD45R/B220 (RA3–6B2), hamster IgG group 1 isotype (G235-2356), hamster IgG group 2 κ isotype (Ha4/8), rat antimouse IgG2a isotype (R35-95), rat antimouse IgG2b isotype (R12-3) and rat IgM κ isotype (R4-22). To identify various cell types, the following antibody combinations were employed: CD3+ (T lymphocytes), B220+ (B lymphocytes), CD3− DX5+ (NK cells), CD3+γδ+ (γδ T lymphocytes) and CD4+ CD25+ (CD4/CD25 T lymphocytes). Cells binding biotinylated antibodies were visualized by staining with avidin–phycoerythrin or avidin–fluorescein isothiocyanate, and dead cells were excluded analytically via staining with propidium iodide (5 µg/ml; Sigma) or 7-aminoactinomycin D (50 µg/ml; Sigma). Each antibody treatment involved incubation of cells with antibody for 30 min on ice. A total of 10 000 cellular events were collected on a Coulter EPICS Elite ESP flow cytometer equipped with a Coherent Innova 90 Argon ion laser and analysed with the ELITE Workstation software (Coulter, FL, USA).

DC preparations

Lymph node cell suspensions were layered onto 2 ml metrizamide (Nycomed, Oslo, Norway; 14·5 g plus 100 ml medium RPMI-1640 (CSL Limited) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum and centrifuged for 20 min at 600 g. Cells at the interface were collected, washed once and resuspended in the appropriate medium. This enrichment procedure routinely increased lymph node CD11c+ cells from 4% to between 30 and 40% in both neonates and adults as determined by flow cytometry (data not shown).

T cell preparations

Spleen cell suspensions were prepared by mild disruption through a 40-µm nylon cell strainer (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) into DMEM-10FCS. The spleen cell suspension was then layered onto 2 ml Histopaque-1077 (Sigma Diagnostics, St Louis, MO, USA; density 1·077 g/ml) and centrifuged for 20 min at 600 g. The cells at the interface were removed, washed once and resuspended in DMEM-10FCS before being incubated within a pre-equilibrated nylon wool column for 1 h at 37°C/10% CO2[20]. The non-adherent cell fraction was then eluted and washed once prior to use. This enrichment procedure routinely produced CD3+ cell purities>70% as determined by flow cytometry (data not shown).

Antigen-specific proliferative assays

Nylon wool enriched T cells, 1·0 × 105, from FITC-immune mice were co-cultured with 2·5 × 104 metrizamide-enriched DC from mice which had been sensitized 18 h prior with FITC in a total of 200 µl DMEM-10FCS in round-bottomed microtitre plates (Greiner, Frickenhansen, Germany) to give a 1 : 4 DC : T cell ratio. Each test group was performed in quadruplicate, and control wells consisted of 2·5 × 104 DC or 1·0 × 105 T cells in isolation in a total of 200 µl DMEM-10FCS. Cells were incubated for 4 days at 37°C/10% CO2 followed by an 18-h incubation in the presence of 1 µCi [3H]thymidine (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech Australia, Tullamarine, Australia) before harvesting on an automatic cell harvester (Skatron Combi Harvester, Sterling, VA, USA) and counted using a liquid scintillation counter (LKB Wallac, Turku, Finland). T cell proliferation was measured by [3H]thymidine incorporation, and results were expressed as a percentage of the adult control, which ranged typically between 20–30 000 cpm.

Accessory cell functional assay (MLR)

Nylon wool-enriched T cells, 1·0 × 105, from the spleens of FVB mice were co-cultured with 2·5 × 104 DC from FITC-sensitized mice in a total of 200 µl DMEM-10FCS in round-bottom microtitre plates (Greiner). To prevent cells from the DC suspension from proliferating in culture, DC preparations were incubated for 20 min at 37°C in DMEM-10FCS containing 50 µg/ml mitomycin C, followed by three washes. To block CD28-mediated co-stimulation of T cells, CTLA-4 Ig (a generous gift from Peter Lane, Basel, Switzerland) was added at a final concentration of 2 mg/ml, as described by Woods et al. [21]. Cultures were incubated for 4 days at 37°C/10% CO2 prior to determination of proliferation by [3H]thymidine incorporation as described above.

RESULTS

Neonatal DC are poor stimulators of antigen-specific T lymphocyte proliferation

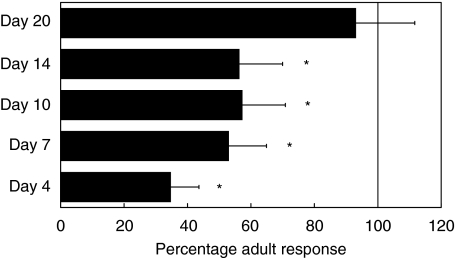

To assess the role that DC play in the development of immunity within the neonate, we analysed the capacity of neonatal DC to deliver antigen-specific APC signals to T cells. DC from FITC-challenged adult mice and neonatal mice of ages 4, 7, 10, 14 and 20 days were cultured with T cells from FITC-immune mice and the resultant proliferative responses compared. DC from day 4 mice were significantly impaired in their ability to generate T lymphocyte division (P < 0·01), achieving only 35% of the mature DC stimulatory capacity (Fig. 1). This capacity improved marginally in DC from mice aged 7, 10 and 14 days, all achieving approximately 50% of the mature signal strength, and by age 20 days the DC stimulatory capacity was indistinguishable from that of the mature control. This demonstrates that lymph node DC from neonatal mice are unable to deliver a positive, antigen-specific proliferative signal to T lymphocytes in response to skin antigenic challenge, and that this ability develops gradually over the first 3 weeks of life.

Fig. 1.

Antigen-specific T cell stimulation by neonatal DC. BALB/c mice of the indicated ages were sensitized with FITC and LN DC populations were isolated 18 h later. DC were cultured with T cells isolated from the spleens of FITC-immune BALB/c mice for a period of 6 days prior to determination of T cell proliferation, expressed as a percentage of the mature control. For the time-points 4, 7, 10 and 14 days, DC failed to achieve significant proliferation, while DC from day 20 mice were not significantly different from the mature control. Each timepoint represents the mean ± standard deviation of quadruplicate cultures from a representative of two experiments.

Neonatal DC possess a reduced co-stimulatory capacity

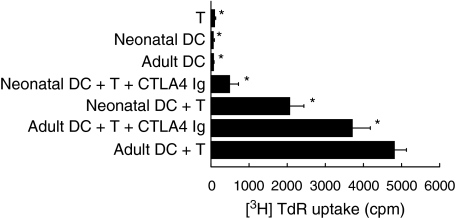

When neonatal DC were co-cultured with allogeneic T lymphocytes they had a significantly reduced ability to induce T cell proliferation compared to adult DC. To determine whether the APC functional deficiency of neonatal DC was due to more than a primary signal deficiency, the co-stimulatory capacity of these cells was determined via a mixed lymphocyte reaction (MLR) assay. BALB/c (H-2d) neonatal and mature DC were cocultured with FVB/N (H-2q) mouse T cells with and without the presence of CTLA-4 Ig. Neonatal DC were able to stimulate only 43% of the T cell proliferation that DC from mature mice were able to achieve (P < 0·01) (Fig. 2), and upon addition of CTLA-4 Ig the accessory cell function of neonatal DC was removed almost completely (13% of the mature control), while the mature DC accessory function was reduced to only 66% of the mature control. Hence neonatal DC are significantly less able than mature DC to provide functional accessory signals to T lymphocytes and are heavily dependent on the B7-CD28 signalling pathway to achieve any T lymphocyte stimulation.

Fig. 2.

Accessory cell function of neonatal DC. DC from BALB/c FITC-treated mice were cultured with T cells from FVB mice, in the presence or absence of anti-CTLA4 Ig for 5 days prior to determination of T cell proliferation. The co-stimulatory function of neonatal DC is impaired in comparision to mature DC, and is heavily dependent on the B7-CTLA4 signalling pathway. The data represent the mean ± standard deviation of quadruplicate cultures from a representative of two experiments.

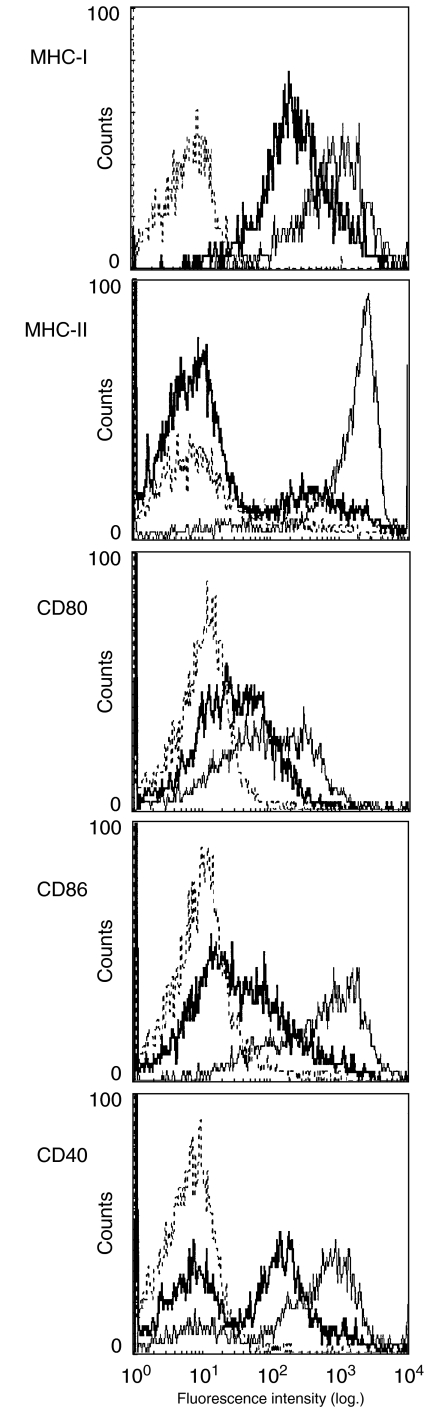

Surface expression of antigen presentation molecules are diminished within neonates

Since neonatal DC were found to be functionally deficient in their ability to provide normal T lymphocyte stimulation, we determined if there were differences in surface expression of those markers involved in APC-T lymphocyte communication. 4-day-old and 6-week-old BALB/c mice were killed 18 h after dorsal skin FITC application, and their draining lymph nodes were removed for DC isolation and analysis. Viable, FITC-positive DC were tested for their expression of MHC class I, MHC class II, CD40, CD80 and CD86. All markers exhibited diminished expression profiles in the neonate compared to the adult (Fig. 3). The largest difference was reserved for MHC class II and CD40, whereas smaller reductions were noted in MHC class II, CD80 and CD86. Because these markers are normally up-regulated during antigen processing and presentation, this indicated that neonatal DC have functional deficiencies in up-regulating those molecules required for fully professional APC activity.

Fig. 3.

Surface expression of antigen presentation molecules on FITC+ dendritic cells. Dendritic cells were enriched over metrizamide, surface stained with antibody and gated according to fluorescence intensity and scatter profiles. Bold histograms represent the neonatal DC, light histograms mature DC and dotted lines are isotype controls.

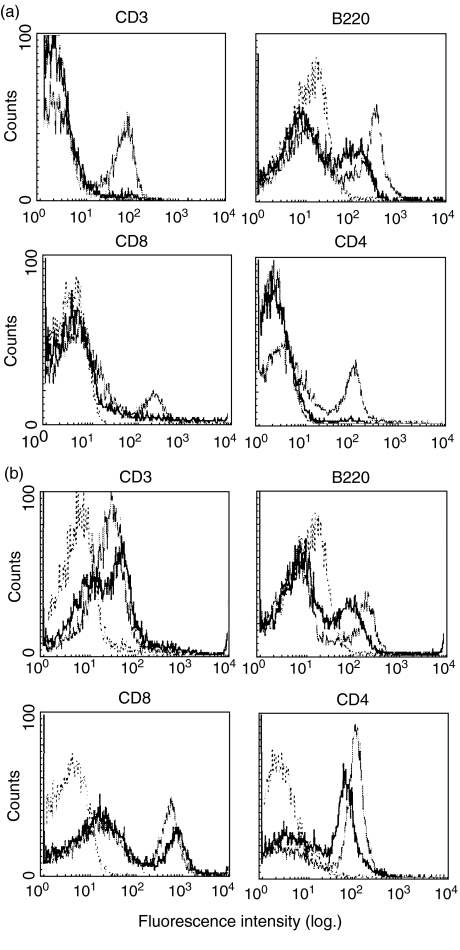

Neonatal LN have normal proportions of classical lymphocytes while neonatal splenic populations are diminished

The above results demonstrate that DC function is diminished within the neonate. The next series of experiments were designed to determine further potential underlying factors in the altered function of the neonatal contact sensitivity response. As a means of gauging cell number deficiencies, the proportions of classical lymphocytes (T and B) in the neonatal spleen (Fig. 4a) and lymph nodes (Fig. 4b) were compared to that of the adult. While it is important to note that the fluorescence intensity of neonatal cells was often reduced, the overall percentages of both cell types within these organs were similar, with the notable exception being the almost complete lack of T lymphocytes within the neonatal spleen. Analysis of T lymphocyte compartments revealed that the neonatal lymph node CD4:CD8 T lymphocyte ratio was normal (between 2 : 1 and 2·5 : 1) and, as expected, the neonatal spleen was almost devoid of CD4+ and CD8+ cells. This indicates that the Th2-inducing environment of the neonate is not due to an imbalance in the expression of classical lymphocytes. Furthermore, due to the absence of T lymphocytes within the neonatal spleen, subsequent analysis of cell populations focused on the lymph nodes as the probable site of memory T cell education within the neonate.

Fig. 4.

Splenic and lymph node expression of CD3, B220, CD4 and CD8 of mature and neonatal mice. Lymphocyte cell suspensions were prepared from the spleen (a) and lymph nodes (b) of neonatal and mature mice 18 h following dorsal skin treatment with DNFB and surface stained with antibody. Bold histograms represent the neonatal DC, light histograms mature DC and dotted lines are isotype controls.

Lymph node expression of non-classical regulatory lymphocytes

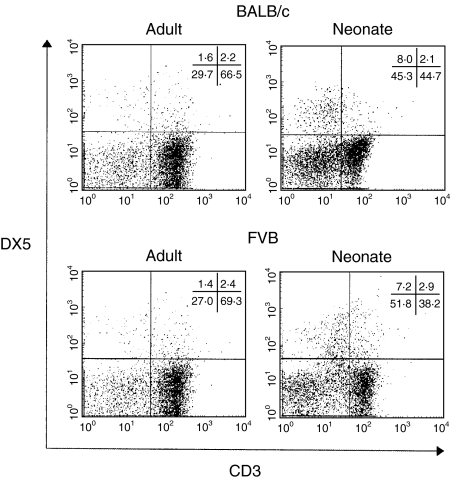

Because the expression of classical lymphocytes in the neonatal lymph nodes were balanced, we chose next to investigate the expression of three known non-classical regulatory lymphocytes; γδ T cells, CD4+CD25+ T cells and NK cells. γδ and CD4+CD25+ T cells were determined to be expressed at equivalent levels within the neonatal and mature lymph nodes (between 1·5 and 2·5%) as demonstrated in Fig. 5. However, the NK cell population (CD3−DX5+) was found initially to have an increased expression in the BALB/c. In order to establish this as a pan-strain characteristic, FVB mice were also tested. In both strains NK cells were represented consistently at 1% of the adult lymph node population, while in the neonatal lymph nodes NK cells were found to be approximately five- to sixfold higher (between 5% and 6%) (Fig. 6).

Fig. 5.

Lymph node populations of CD4+CD25+ and CD3+γδ+. Lymphocyte cell suspensions were prepared from the spleen and lymph nodes of neonatal and mature mice 18 h following dorsal skin treatment with DNFB and surface stained with antibody.

Fig. 6.

Natural Killer (CD3−DX5+) cell representation in BALB/c and FVB mouse lymph nodes. Lymphocyte cell suspensions were prepared from lymph nodes of BALB/c and FVB neonates and adults 18 h after dorsal skin treatment with DNFB. Suspensions were surface stained with CD3 and DX5 antibodies.

DISCUSSION

This study implicates Langerhans cells in the impaired ability of newborn mice to generate cell-mediated contact sensitivity responses. We have demonstrated that these cells are unable to employ the CD40–CD40 ligand co-stimulatory pathway as a means of generating T cell division. Through a numerical analysis of lymphocyte populations, we have also shown that the lymph nodes of the neonate possess levels of classical and regulatory non-classical lymphocytes similar to that of the adult, with the exception of a striking elevation in the presence of NK cells.

The current understanding of the neonatal immune system suggests that Th1 responses are minimal or absent and are more easily tolerized than Th2 responses [22], which are generally dominant and retained as the memory response [10]. Thus vertebrates exposed to known sensitizing agents during the neonatal period fail to generate strong cell-mediated immune responses when re-exposed to the antigen later in life. The cause of this skewing of both the immediate and long-term immune response is unclear. Hence we compared the immune system of the neonate and the adult mouse, with an emphasis on analysing cell number, phenotype and function of a variety of immune cells.

Splenic T cell number and function within the neonate has been identified as one of the prime causes of immunological hyporeactivity and the subsequent development of tolerance [11,23,24]. More recently, it has become clear that the spleen differs from the lymph nodes within the neonate with regard to their lymphocyte population ratios and the primary immune responses they generate [25,26]. We confirmed this observation in the BALB/c neonate, demonstrating a low number of T cells within the spleen, whereas the lymph nodes had a relatively normal proportion of T cells and a normal CD4+ : CD8+ lymphocyte ratio. There were no differences in splenic or lymph node B cell populations in the neonate. It would therefore seem more likely that the generation of the immune response in neonatal mice initially occurs in the lymph nodes, whether this results in immunity or suppression. This is supported by a recent observation that the neonatal spleen is not required for the generation of dominant Th2 memory responses [25].

Part of the phenotypical analysis of the neonatal immune environment involved the enumeration of two known regulatory (i.e. suppressive) lymphocytes within the lymph nodes. CD4+CD25+ T lymphocytes have been implicated as being responsible for the tolerance to allografts [27] and the prevention of autoimmune reactions [28,29]. Their regulatory reactions are proposed to take place at the DC interface [30], thus there is a possibility that their regulatory behaviour is instigated upon interaction with DC. γδ T cells have also been implicated as being influential in several forms of tolerance, including oral tolerance [31], tumour tolerance [32] and immune-privileged site tolerance observed in anterior chamber associated immune deviation (ACAID) [33] and in the testis [34]. These cells were present within the neonatal lymph nodes, but in similar proportions to the adult nodes, indicating that deviation of the immune response at this time is not the result of an increased number of these cells. However, this does not rule out the possibility that these cells are responsible for the maintenance of suppression in neonatally tolerized adult animals.

As there was a normal lymphocyte balance within the neonatal lymph nodes, and considering evidence of neonatal T cell competence in responding to antigen presentation by adult DC [11,35], we chose to investigate whether lymph node APC function was contributing to the immune deviation of the neonate. Following skin challenge, DC in neonatal lymph nodes carry less antigen than their adult counterparts, and these mice fail to develop contact hypersensitivity when challenged by the same antigen as an adult [36]. We now demonstrate that neonatal DC are ineffective in delivering a proliferative signal to T cells. As this deficiency will have a major impact on the balance of neonatal immune responses, it was necessary to clarify the underlying cause. The ability of these DC to deliver co-stimulatory signals to T cells was reduced significantly, and the addition of CTLA-4 Ig blocked the residual co-stimulatory activity. Consequently the weakened co-stimulatory activity of these cells is totally dependent on the B7/CD28 pathway and the CD40–40 L signalling pathway is non-functional. This failure to utilize CD40 signalling is supported by the reduced surface expression of CD40 evident on antigen-bearing neonatal lymph node DC.

The CD40–40 ligand-receptor combination is a critical part of normal in vivo responses (reviewed in [37]). The CD40–40 L interaction has been shown to drive IL-12 production by APCs [38–40] and promote differentiation to Th1 during priming of T cell responses [41,42]. As such, the absence or blocking of CD40 signalling can lead to deficient induction of Th1-type responses, allowing long-term allograft survival [43] and the suppression of CHS responses [44]. Deficient expression of the CD40 molecule by APCs may therefore be important to neonatally developed tolerance and the prevention of autoimmune diseases, the likelihood of which is discussed in detail by Thompson and Thomas [45]. Furthermore, evidence of a deficiency within IL-12 production by neonatal DC has been gathered in human tests [46], and preliminary tests in our own laboratory indicate that the IL-12 p35 subunit expression is reduced within the neonatal lymph nodes (data not shown). We therefore consider it likely that this absence of CD40 signalling plays an important role in the skewing of the neonatal immune response to Th2 via the reduction of Th1 activity. It is also likely that the low expression of MHC class II of these DC also contributes to the reduced immune response of the neonate. This may partially explain why the neonate has few MHC class II positive cells within its circulation [47], which has been shown to be critical to neonatal graft tolerance [48]. Other APC types and their deficiencies should also be considered, as it has been demonstrated recently that skin-applied hapten may reach the lymph nodes and other tissues without being bound and transported by any cell type [49]. Thus, other APC that have been demonstrated to induce anergy through incomplete T cell signalling, such as B cells [50], may also process skin-applied antigen and subsequently contribute to the antigen-specific immune deviation within the neonate.

An intriguing finding from the enumeration of neonatal lymph node lymphocyte populations conducted in this study was the greater proportion of natural killer (NK) cells within the neonatal lymph nodes. This unusually high proportion of NK cells may be indicative of an important regulatory role during development life, perhaps including a role in establishing peripheral tolerance. There are numerous reports of a variety of NK activities that may influence Th response developments. Initial reports that DC which have interacted with antigen were targets for NK cells [51] have been explained by recent observations that human and murine NK cells can be triggered to mediate lysis by interacting with the co-stimulatory molecules CD40, CD80 and CD86 [52–56]. Furthermore, immature DC expressing these molecules in combination with a reduced level of MHC class I are susceptible to NK-mediated lysis, while more mature DC with higher levels of MHC class I are protected [57,58]. The antigen-carrying DC within neonatal draining lymph nodes in this study have reduced co-stimulatory molecule and MHC class II expression and, more importantly, demonstrate reduced MHC class I expression. It is therefore attractive to suggest that NK cells interact with antigen-carrying DC, which may result in a reduction in immunocompetent DC and a subsequent shifting in the balance of the final response. A further possible role for NK activity in the generation of antigen-specific regulatory cells could occur via transforming growth factor (TGF)-β production. NK cells have been shown to be critical to the induction of CD8+ suppressor effector cells through their TGF-β secretion [59] and TGF-β production by lymphocytes has been shown to be decreased in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) [60]. It is interesting to note that NK cell function is often impaired in many autoimmune diseases, such as SLE and multiple sclerosis [61,62]; thus it may be that either of the two roles for NK cells in the generation of tolerance we propose here may be interrupted during such diseases.

In summary, the findings from this study support our previous proposal that neonatal DC induce antigen-specific unresponsiveness rather immunity. The most probable site of tolerance induction to cutaneous antigen within the neonate is the lymph nodes, because normal levels of T and B lymphocytes are located here alongside antigen-bearing and CD40-deficient DC. A key area yet to be addressed is the cause of the various neonatal DC deficiencies. These findings have important implications for the future design of therapeutic strategies against autoimmune diseases.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grant no.107914 from the National Health and Medical Research Council (Australia). The authors would like to acknowledge Mr Mark Cozens for his valuable assistance with flow cytometry.

References

- 1.Billingham RE, Brent L, Medawar PB. ‘Actively acquired tolerance’ of foreign cells. Nature. 1953;172:603–6. doi: 10.1038/172603a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chiller JM, Romball CG, Weigle WO. Induction of immunological tolerance in neonatal and adult rabbits. Differences in the cellular events. Cell Immunol. 1973;8:28–39. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(73)90090-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adorini L, Harvey MA, Miller A, et al. Fine specificity of regulatory T cells. II. Suppressor and helper T cells are induced by different regions of hen egg-white lysozyme in a genetically nonresponder mouse strain. J Exp Med. 1979;150:293–306. doi: 10.1084/jem.150.2.293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nossal GJ. Cellular mechanisms of immunologic tolerance. Annu Rev Immunol. 1983;1:33–62. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.01.040183.000341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Petersen JS, Karlsen AE, Markholst H, et al. Neonatal tolerization with glutamic acid decarboxylase but not with bovine serum albumin delays the onset of diabetes in NOD mice. Diabetes. 1994;43:1478–84. doi: 10.2337/diab.43.12.1478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Qin YF, Sun DM, Goto M, et al. Resistance to experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis induced by neonatal tolerization to myelin basic protein: clonal elimination vs. regulation of autoaggressive lymphocytes. Eur J Immunol. 1989;19:373–80. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830190223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clayton JP, Gammon GM, Ando DG, et al. Peptide-specific prevention of experimental allergic encephalomyelitis. Neonatal tolerance induced to the dominant T cell determinant of myelin basic protein. J Exp Med. 1989;169:1681–91. doi: 10.1084/jem.169.5.1681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gammon G, Dunn K, Shastri N, et al. Neonatal T-cell tolerance to minimal immunogenic peptides is caused by clonal inactivation. Nature. 1986;319:413–5. doi: 10.1038/319413a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Waters CA, Pilarski LM, Wegmann TG, et al. Tolerance induction during ontogeny. I. Presence of active suppression in mice rendered tolerant to human gamma-globulin in utero correlates with the breakdown of the tolerant state. J Exp Med. 1979;149:1134–51. doi: 10.1084/jem.149.5.1134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singh RR, Hahn BH, Sercarz EE. Neonatal peptide exposure can prime T cells and, upon subsequent immunization, induce their immune deviation: implications for antibody vs. T cell-mediated autoimmunity. J Exp Med. 1996;183:1613–21. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.4.1613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ridge JP, Fuchs EJ, Matzinger P. Neonatal tolerance revisited. turning on newborn T cells with dendritic cells. Science. 1996;271:1723–6. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5256.1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stockinger B. Neonatal tolerance mysteries solved. Immunol Today. 1996;17:249. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(96)80534-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Flamand V, Donckier V, Demoor FX, et al. CD40 ligation prevents neonatal induction of transplantation tolerance. J Immunol. 1998;160:4666–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li L, Legge KL, Min B, et al. Neonatal immunity develops in a transgenic TCR transfer model and reveals a requirement for elevated cell input to achieve organ-specific responses. J Immunol. 2001;167:2585–94. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.5.2585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Adkins B, Bu Y, Guevara P. Murine neonatal CD4+ lymph node cells are highly deficient in the development of antigen-specific Th1 function in adoptive adult hosts. J Immunol. 2002;169:4998–5004. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.9.4998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adkins B, Hamilton K. Freshly isolated, murine neonatal T cells produce IL-4 in response to anti-CD3 stimulation. J Immunol. 1992;149:3448–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Adkins B, Ghanei A, Hamilton K. Developmental regulation of IL-4, IL-2, and IFN-gamma production by murine peripheral T lymphocytes. J Immunol. 1993;151:6617–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adkins B, Ghanei A, Hamilton K. Up-regulation of murine neonatal T helper cell responses by accessory cell factors. J Immunol. 1994;153:3378–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lu CY, Beller DI, Unanue ER. During ontogeny, Ia-bearing accessory cells are found early in the thymus but late in the spleen. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1980;77:1597–601. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.3.1597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hathcock KS. T cell enrichment by nonadherence to nylon. In: Colignan JE, Kruisbeek DH, Marguiles DH, et al., editors. Current protocols in immunology. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 1992. pp. 3.2.1–3.2.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Woods GM, Doherty KV, Malley RC, et al. Carcinogen-modified dendritic cells induce immunosuppression by incomplete T-cell activation resulting from impaired antigen uptake and reduced CD86 expression. Immunology. 2000;99:16–22. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2000.00928.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Romball CG, Weigle WO. In vivo induction of tolerance in murine CD4+ cell subsets. J Exp Med. 1993;178:1637–44. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.5.1637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holan V, Lipoldova M, Zajicova A. Immunological nonreactivity of newborn mice: immaturity of T cells and selective action of neonatal suppressor cells. Cell Immunol. 1991;137:216–23. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(91)90070-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Borghans JA, de Boer RJ. Neonatal tolerance revisited by mathematical modelling. Scand J Immunol. 1998;48:283–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.1998.00398.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Adkins B, Bu Y, Cepero E, et al. Exclusive Th2 primary effector function in spleens but mixed Th1/Th2 function in lymph nodes of murine neonates. J Immunol. 2000;164:2347–53. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.5.2347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Astori M, Finke D, Karapetian O, et al. Development of T–B cell collaboration in neonatal mice. Int Immunol. 1999;11:445–51. doi: 10.1093/intimm/11.3.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kingsley CI, Karim M, Bushell AR, et al. CD25+CD4+ regulatory T cells prevent graft rejection. CTLA-4 and IL-10-dependent immunoregulation of alloresponses. J Immunol. 2002;168:1080–6. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.3.1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sakaguchi S, Sakaguchi N, Asano M, et al. Immunologic self-tolerance maintained by activated T cells expressing IL-2 receptor alpha-chains (CD25). Breakdown of a single mechanism of self-tolerance causes various autoimmune diseases. J Immunol. 1995;155:1151–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Itoh M, Takahashi T, Sakaguchi N, et al. Thymus and autoimmunity: production of CD25+CD4+ naturally anergic and suppressive T cells as a key function of the thymus in maintaining immunologic self-tolerance. J Immunol. 1999;162:5317–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cederborn L, Hall H, Ivars F. CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells downregulate co-stimulatory molecules on antigen-presenting cells. Eur J Immunol. 2000;30:1538. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200006)30:6<1538::AID-IMMU1538>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ke Y, Pearce K, Lake JP, et al. Gamma delta T lymphocytes regulate the induction and maintenance of oral tolerance. J Immunol. 1997;158:3610–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Seo N, Egawa K. Suppression of cytotoxic T lymphocyte activity by gamma/delta T cells in tumor-bearing mice. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 1995;40:358–66. doi: 10.1007/BF01525386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Skelsey ME, Mellon J, Niederkorn JY. Gamma delta T cells are needed for ocular immune privilege and corneal graft survival. J Immunol. 2001;166:4327–33. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.7.4327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mukasa A, Hiromatsu K, Matsuzaki G, et al. Bacterial infection of the testis leading to autoaggressive immunity triggers apparently opposed responses of alpha beta and gamma delta T cells. J Immunol. 1995;155:2047–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Adkins B. T-cell function in newborn mice and humans. Immunol Today. 1999;20:330–5. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(99)01473-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dewar AL, Doherty KV, Woods GM, et al. Acquisition of immune function during the development of the Langerhans cell network in neonatal mice. Immunology. 2001;103:61–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2001.01221.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mackey MF, Barth RJ, Jr, Noelle RJ. The role of CD40/CD154 interactions in the priming, differentiation, and effector function of helper and cytotoxic T cells. J Leukoc Biol. 1998;63:418–28. doi: 10.1002/jlb.63.4.418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kelsall BL, Stuber E, Neurath M, et al. Interleukin-12 production by dendritic cells. The role of CD40–CD40L interactions in Th1 T-cell responses. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1996;795:116–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1996.tb52660.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cella M, Scheidegger D, Palmer-Lehmann K, et al. Ligation of CD40 on dendritic cells triggers production of high levels of interleukin-12 and enhances T cell stimulatory capacity: T–T help via APC activation. J Exp Med. 1996;184:747–52. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.2.747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kato T, Hakamada R, Yamane H, et al. Induction of IL-12 p40 messenger RNA expression and IL-12 production of macrophages via CD40–CD40 ligand interaction. J Immunol. 1996;156:3932–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Campbell KA, Ovendale PJ, Kennedy MK, et al. CD40 ligand is required for protective cell-mediated immunity to Leishmania major. Immunity. 1996;4:283–9. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80436-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stuber E, Strober W, Neurath M. Blocking the CD40L–CD40 interaction in vivo specifically prevents the priming of T helper 1 cells through the inhibition of interleukin 12 secretion. J Exp Med. 1996;183:693–8. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.2.693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lu L, Li W, Fu F, et al. Blockade of the CD40–CD40 ligand pathway potentiates the capacity of donor-derived dendritic cell progenitors to induce long-term cardiac allograft survival. Transplantation. 1997;64:1808–15. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199712270-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tang A, Judge TA, Turka LA. Blockade of CD40–CD40 ligand pathway induces tolerance in murine contact hypersensitivity. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:3143–50. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830271210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thompson AG, Thomas R. Induction of immune tolerance by dendritic cells: implications for preventative and therapeutic immunotherapy of autoimmune disease. Immunol Cell Biol. 2002;80:509–19. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1711.2002.01114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Goriely S, Vincart B, Stordeur P, et al. Deficient IL-12 (p35) gene expression by dendritic cells derived from neonatal monocytes. J Immunol. 2001;166:2141–6. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.3.2141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chernishov VP, Slukvin II. Mucosal immunity of the mammary gland and immunology of mother/newborn interrelation. Arch Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz) 1990;38:145–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.White DJ, Gilks W. The ontogeny of immune responses. J Heart Lung Transplant. 1993;12:S301–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pior J, Vogl T, Sorg C, et al. Free hapten molecules are dispersed by way of the bloodstream during contact sensitization to fluorescein isothiocyanate. J Invest Dermatol. 1999;113:888–93. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1999.00770.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ozaki ME, Coren BA, Huynh TN, et al. CD4+ T cell responses to CD40-deficient APCs: defects in proliferation and negative selection apply only with B cells as APCs. J Immunol. 1999;163:5250–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shah PD, Gilbertson SM, Rowley DA. Dendritic cells that have interacted with antigen are targets for natural killer cells. J Exp Med. 1985;162:625–36. doi: 10.1084/jem.162.2.625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Geldhof AB, Raes G, Bakkus M, et al. Expression of B7-1 by highly metastatic mouse T lymphomas induces optimal natural killer cell-mediated cytotoxicity. Cancer Res. 1995;55:2730–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chambers BJ, Salcedo M, Ljunggren HG. Triggering of natural killer cells by the co-stimulatory molecule CD80 (B7-1) Immunity. 1996;5:311–7. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80257-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Geldhof AB, Moser M, Lespagnard L, et al. Interleukin-12-activated natural killer cells recognize B7 co-stimulatory molecules on tumor cells and autologous dendritic cells. Blood. 1998;91:196–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Martin-Fontecha A, Assarsson E, Carbone E, et al. Triggering of murine NK cells by CD40 and CD86 (B7–2) J Immunol. 1999;162:5910–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wilson JL, Charo J, Martin-Fontecha A, et al. NK cell triggering by the human co-stimulatory molecules CD80 and CD86. J Immunol. 1999;163:4207–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hoglund P, Ohlen C, Carbone E, et al. Recognition of beta 2-microglobulin-negative (beta 2m-) T-cell blasts by natural killer cells from normal but not from beta 2m- mice: nonresponsiveness controlled by beta 2m- bone marrow in chimeric mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:10332–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.22.10332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Carbone E, Terrazzano G, Ruggiero G, et al. Recognition of autologous dendritic cells by human NK cells. Eur J Immunol. 1999;29:4022–9. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199912)29:12<4022::AID-IMMU4022>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gray JD, Hirokawa M, Horwitz DA. The role of transforming growth factor beta in the generation of suppression: an interaction between CD8+ T and NK cells. J Exp Med. 1994;180:1937–42. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.5.1937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ohtsuka K, Gray JD, Stimmler MM, et al. Decreased production of TGF-beta by lymphocytes from patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Immunol. 1998;160:2539–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Katz P, Zaytoun AM, Lee JH, Jr, et al. Abnormal natural killer cell activity in systemic lupus erythematosus: an intrinsic defect in the lytic event. J Immunol. 1982;129:1966–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Benczur M, Petranyl GG, Palffy G, et al. Dysfunction of natural killer cells in multiple sclerosis: a possible pathogenetic factor. Clin Exp Immunol. 1980;39:657–62. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]