Abstract

It is well known that monocytes may play an active role in thrombogenesis, since they may express on their surface tissue factor, the major initiator of the clotting cascade. The results of this investigation demonstrate beta-2-glycoprotein I (β2-GPI) mRNA expression by human peripheral blood monocytes, indicating that these cells synthesize β2-GPI. In addition, we show β2-GPI expression on cell surface of these cells by flow cytometric analysis, and the presence of this protein in cell lysate by Western blot. Interestingly, β2-GPI expression on monocytes is significantly increased in patients with anti-phospholipid syndrome (APS) or systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) as against healthy blood donors and correlates with tissue factor expression on monocytes. These findings support the view that monocytes are able to synthesize β2-GPI and suggest that patients with APS may have increased β2-GPI exposure on cell surface, which leads to persistently high monocyte tissue factor expression and consequently to a prothrombotic diathesis.

Keywords: β2-glycoprotein I, tissue factor, monocytes, anti-phospholipid antibodies, anti-β2-GPI

INTRODUCTION

Anti-phospholipid syndrome (APS) is a clinical entity characterized by serum antiphospholipid antibodies (aPL) associated to morbid manifestations, such as arterial and venous thrombosis, recurrent abortions and/or foetal death [1–3].

Beta2-glycoprotein I (β2-GPI) is a plasma glycoprotein capable of binding to anionic phospholipids and a cofactor required for the formation of the antigenic epitopes of some aPL. In patients with APS antibodies directed only against β2-GPI have been detected [4,5], and it was demonstrated that aPL and ‘pure’ anti-β2-GPI represent two distinct and not cross-reagent specificities [6]. Moreover, anti-β2-GPI antibodies have been more closely associated with thrombosis occurring in APS than aCL [7]. A direct pathogenic role for anti-β2-GPI antibodies in APS has been suggested by the demonstration that these antibodies can activate endothelial cells in vitro and that the passive immunization of mice with these antibodies results in an experimental model of APS in vivo[8]. Moreover, it was shown that these antibodies induce a remarkable increase in tissue factor activity of endothelial cells [8].

Although hepatocytes represent the main site of β2-GPI synthesis [9], the presence of β2-GPI mRNA has been demonstrated, by RT-PCR, in fetal astrocytes, in cells from intestine and placenta [10,11]. More recently, we also detected β2-GPI mRNA in endothelial cells, lymphocytes, astrocytes and neurones [12]. All these cell lines were bound by anti-β2-GPI antibodies, a finding which suggests that β2-GPI is expressed and synthesized by several cell types virtually involved in APS pathogenesis [12,13].

Furthermore, monocytes play an active role in thrombogenesis, since, once activated, these cells express tissue factor (TF), the major initiator of the clotting cascade, on their surface [14]. Recently, in vitro and in vivo data suggest a role for monocyte TF in APS [15–17], although a definitive role in the pathophysiology of the syndrome is not yet established. However, a number of studies demonstrated that the incubation of monocytes with β2-GPI-dependent anti-cardiolipin antibodies resulted in an increase in TF mRNA synthesis and TF expression on monocyte surface [15–17].

In this study, we firstly performed RT-PCR to investigate β2-GPI mRNA expression by monocytes from normal subjects. We subsequently investigated whether β2-GPI expression on the surface of monocytes was modified in patients with SLE and APS and if there was a relationship between TF expression, β2-GPI expression, anti-β2-GPI antibodies and aPL serum levels.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients and controls

Seventeen consecutive outpatients with APS (13 female, 4 male; mean age 33·6 years, range 6–50 year) diagnosed according to the Sapporo criteria [3] (7 primary and 10 secondary to SLE) were enrolled. Fifteen consecutive SLE outpatients without signs of APS (13 female, 2 male; mean age 39·4 years, range 22–60 years) fulfilling ACR criteria [18] and 15 healthy donors (12 female, 3 male; mean age 39 years, range 28–52 years) were included as controls. All the patients referred to the Division of Rheumatology of the University of Rome ‘La Sapienza’.

After obtained informed consent, each subject underwent peripheral blood sample collection. The serum recovered was then stored at –20°C until assayed.

The clinical features of the APS and SLE patients are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

The clinical features of the APS and SLE patients

| Variable | APS (n = 17) | SLE (n = 15) |

|---|---|---|

| Females/males | 13/4 | 13/2 |

| Age(years) | ||

| Mean | 33·6 | 39·4 |

| Range | 6–50 | 22–60 |

| Disease duration (months) | ||

| Mean | 97 | 110 |

| Range | 1–322 | 1–240 |

| Venous thromboses | 10 | 0 |

| Arterial thromboses | 9 | 0 |

| Recurrent thromboses | 8 | 0 |

| Miscarriages/pregnancy | 7/9 | 3/9 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 4 | 3 |

Monocyte preparation

Human peripheral blood mononuclear cells were isolated from fresh heparinized blood by Lymphoprep (Nycomed AS Pharma Diagnostic Division, Oslo, Norway) density-gradient centrifugation and washed three times in phosphate buffered saline (PBS), pH 7·4. Monocytes were isolated by counterflow centrifugal elutriation according to the Current Protocols in Immunology [19]. Monocyte populations were washed with RPMI 1640 and placed in serum-free medium, containing 5 mM insulin, 5 mM transferrine, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 mg/ml streptomycin, 250 pg/ml fungizone and 2 mM L-glutamine (obtained from Gibco BRL, Life Technologies Italia srl, Milano, Italy) for 24 h at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere.

The purity of monocyte preparation was checked by cytofluorimetric analysis by FITC-conjugated anti-CD14 (IgG2a κ isotype, DAKO S.p.A.) (5 µl/106 cells). All preparations contained up to 80% of anti-CD14 positive cells.

Western blot analysis of β2-GPI expression

Whole cells (human monocytes and as a negative control normal skin fibroblasts) were lysed in lysis buffer (20 mM HEPES, pH 7·2, 1% Nonidet P-40, 10% glycerol, 50 mM NaF, 1 mM phenylmethylsulphonyl fluoride, 10 µg of leupeptin per ml). The proteins were separated by 10% sodium dedecyl sulphate polyacrilamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), electrophoretically transferred to nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) and then probed with polyclonal rabbit anti-human β2-GPI (Chemicon Int., Temecula, CA, USA). Bound antibodies were then visualized with peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (Sigma). The colour reaction was obtained by adding 200 mg of sodium nitroprusside (Sigma), 80 mg of o-dianisidine (Sigma), dissolved in 100 ml H2O, containing 35 µl of 30% H2O2. The reaction was stopped by washing in distilled water.

Detection of β2-GPI mRNA by RT-PCR

Detection of β2-GPI mRNA by RT-PCR was performed as previously described [12]. Hepatoma line HEpGL2 (kindly provided by Rita Nicotra, Istituto Regina Elena, Roma, Italy) were used as positive control according to Avery et al. [10] and Chamley et al. [11] and normal skin fibroblasts as negative control. Cell lines were cultured in their usual medium supplemented by 5–20% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and gentamycin (0·05 mg/ml) (Gibco BRL). After 3 days, one sample of each cell line was repeatedly washed in PBS, pH 7·3, to remove the culture medium and then analysed. Total RNAs, extracted from monocytes and control cell lines by ultraspec RNA isolation system (Biotecx) according to the manufacturer's instruction, were treated with DNAse I, RNAse free (Gibco BRL) and then converted to first-strand cDNA copes by random primers of 4 µg of total RNA with Super Script H-RNAse RT as suggested by the supplier (Gibco BRL). Oligonucleotide primers designed for PCR amplification of the human β2-GPI and β-actin mRNAs were checked by Genebank. Based on the coding sequences [20,21] the following primers were used: β2-GPI-F 5′-TCTGCCATGCCAAGTTGTAAAG-3′ (784–805); β2-GPI-R 5′-CATCGGATGCATCAGTTTTCCA-3′ (1045–1024); β-actin-F 5′-AAGAGAGGCATCCTCACCCT-3′ (222–241); β-actin-F 5′-TACATGGCTGGGGTGTTGAA-3′ (439–420) [22]. One-fourth of cDNA synthesis reaction volume was combined in a 100-µl final volume for PCR amplification containing each primer and Taq polymerase (Gibco BRL). PCR was performed for either 35 (β2-GPI) or 25 (β-actin) cycle, each cycle consists of denaturation at 94°C (45 s), annealing at 60°C (30 s), extension at 72°C (30 s), after predenaturation at 95°C (2 min), and final extension at 72°C (10 min). Ten microlitres of the RT-PCR products were submitted to a second PCR using the same primers for β2-GPI. Fifteen microlitres of the PCR products were run on 2% agarose gels in TAE buffer. To rule out the possibility of amplification of contaminating genomic DNA, RNA samples treated with DNAse were submitted to PCR amplification without RT.

Immunofluorescence and flow cytometric analysis

Indirect immunofluorescence was performed to analyse β2-GPI expression on cell plasma membrane of monocytes. One × 106 cells were fixed in 4% formaldehyde/PBS for 1 h at 4°C. After washing three times with PBS, cells were incubated with a rabbit polyclonal anti-human β2-GPI (Chemicon Int.) or, alternatively, with anti-human β2-GPI 1A4 MoAb [12], in PBS/1% BSA, for 1 h at 4°C. Phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG or anti-mouse IgG (γ-chain specific, Sigma) were then added and incubated at 4°C for 30 min After washing with PBS, cells were incubated with FITC-conjugated monoclonal antibodies (MoAb) anti-CD14 (Sigma) or anti-human tissue factor (American Diagnostica Inc. Greenwich, CT, USA) for 45 min at 4°C. The fluorescence intensity was analysed with a Becton Dickinson cytometer. Cells were gated on the basis of forward angle light scatter and 90° light scatter parameters.

Separately, in parallel experiments, cells were directly stained with anti-β2-GPI Ab before fixing the cells with 4% formaldehyde in PBS, revealing that fixation procedures did not affect β2-GPI staining on the cell surface.

Evaluation of DNA fragmentation

Monocytes were placed in serum-free medium for 24 h at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere as above. DNA fragmentation was studied by propidium iodide staining followed by flow cytometric analysis (EPICS Profile, Coulter Electronics, Hialeah, FL, USA). Cells were fixed with cold 70% ethanol in PBS for 1 h at 4°C. After centrifugation at 200 g for 10 min at 4°C, cells were washed once in PBS. The pellet was resuspended in 0·5 ml PBS, 50 µl of RNAse (Type I-A, Sigma, 10 mg/ml in PBS) was added, followed by 50 µg/ml propidium iodide (Sigma) in PBS. The cells were incubated in the dark at room temperature for 15 min and kept at 4°C until measured. A Trypan blue exclusion test was performed to evaluate the viability of the cultures.

Detection of β2-GPI serum levels by ELISA

β2-GPI serum levels were detected by a slight modification of an ELISA method previously reported [23]. Polystyrene plates were coated (100 µl/well) overnight at 4°C, with the IgG mouse anti-human β2-GPI 1A4 MoAb [12], 5 µg/ml in PBS. After washing two times with PBS, the plates were blocked by incubation for 1 h at 25°C with a solution of PBS-1% milk. After washing four times with PBS-0·1% milk-0·1% tween 20, sera (100 µl/well; 1 : 5000 in PBS-0·1% milk-0·1% tween 20) were added and incubated for 1 h at 25°C. After washing four times, rabbit polyclonal anti-human β2-GPI (Chemicon Int.) (100 µl/well; 1 : 1000 in PBS-0·1% milk-0·1% tween 20) was added and incubated for 1 h at 25°C. After washing four times, alkaline phosphatase-conjugated mouse anti-rabbit IgG (100 µl/well; 1 : 1000 in PBS-0·1% milk-0·1% tween 20) was added and incubated for 1 h at 25°C. After washing four times, 100 µl of p-nitrophenylphosphate solution was added and the optical density (OD) was read at 405 nm wavelength. The β2-GPI serum levels were calculated according to a standard curve obtained from a pool of normal human sera calibrated on purified human β2-GPI (Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA, USA), as previously described [23].

Anti-CL and anti-β2-GPI antibodies evaluations

Sensitive and specific commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA; Diamedix, Miami, Fl, USA) were used to measure anti-CL and anti-β2-GPI antibodies. Results were expressed as international units (IU) according to manufacturer's instructions.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out using Mann–Whitney's U-test for comparison of means between the different groups of patients or between patients and controls. Spearman's rank correlation coefficient was applied for calculation of the correlation between parallel variables in single patients. The frequencies of the autoantibodies studied between patients and controls were compared by the χ2 test. A P-value < 0·05 was considered as statistically significant.

RESULTS

β2-GPI expression in human monocytes

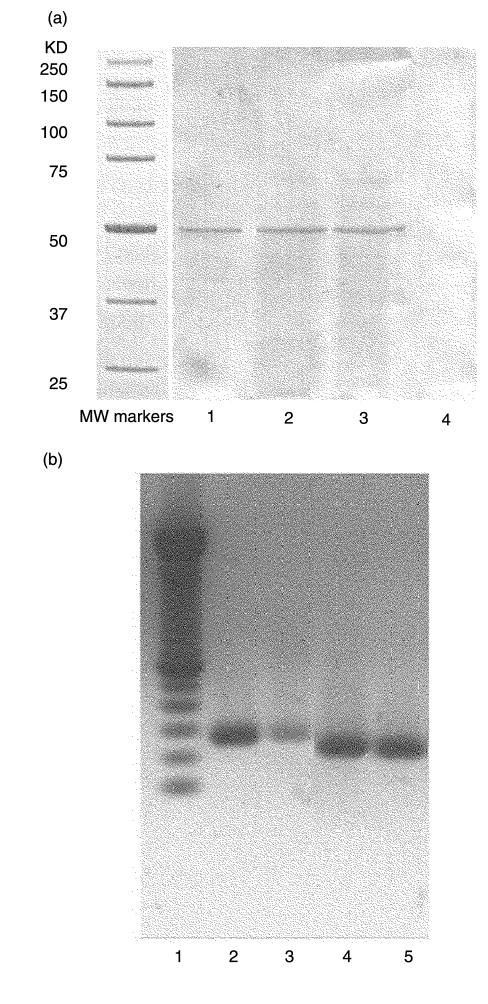

In order to detemine whether β2-GPI is expressed in human monocytes, cell-free lysates were analysed by Western blot, using a polyclonal anti-β2-GPI Ab. The analysis revealed a 50-kDa band, comigrating with standard β2-GPI both in the presence and in the absence of FCS. No bands were detected in the lysate from human skin fibroblasts (Fig. 1a).To clarify whether β2-GPI was really synthesized by these cells, the expression of mRNA for β2-GPI was evaluated in human monocytes isolated from peripheral blood. As shown in Fig. 1b, the β2-GPI mRNA was identified in human monocytes. The RT-PCR of RNAs resulted in amplification of the expected bands, i.e. 262 bp for β2-GPI. According to our previous paper [12], no bands were detected in human skin fibroblasts (not shown). The possibility of amplification of contaminating genomic DNA was excluded, since no products were obtained from the RNA samples subjected to PCR without RT. Moreover, the β-actin-specific primer pairs were selected from two exons separated by one intronic sequence [22]. As shown in Fig. 1b, the RT-PCR product of β-actin mRNA (218 bp), but no gene fragment (659 bp) was observed.

Fig. 1.

(a) Western blot analysis of β2-GPI expression in human monocytes. Monocytes were washed with RPMI 1640 and placed in serum-free medium, containing 5 mM insulin, 5 mM transferrine, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 mg/ml streptomycin and 250 pg/ml fungizone, 2 mM L-glutamine for 24 h at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere. Whole cells were lysed in lysis buffer. The proteins were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE, electrophoretically transferred to nitrocellulose membrane and then probed with polyclonal anti-human β2-GPI. Bound antibodies were then visualized with peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG. The colour reaction was obtained by sodium nitroprusside. Lane 1: standard β2-GPI, 2 µg; lane 2: monocytes placed in serum-free medium without FCS; lane 3: monocytes placed in medium with 10% FCS; lane 4: human skin fibroblasts. (b) Reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) products of mRNAs for β2-GPI from human monocytes. Lane 1: 50-bp DNA ladder: lane 2: RT-PCR products of mRNAs for β2-GPI from HepGL2; lane 3: RT-PCR products of mRNAs for β2-GPI from human monocytes; lane 4: RT-PCR products of mRNAs for β-actin from HepGL2; lane 5: RT-PCR products of mRNAs for β-actin from human monocytes. The RT-PCR of RNAs results in amplification of the expected bands: 262 bp for β2-GPI, 218 bp for β-actin.

Increase of β2-GPI expression in monocytes of patients with APS and SLE and relationship with tissue factor expression

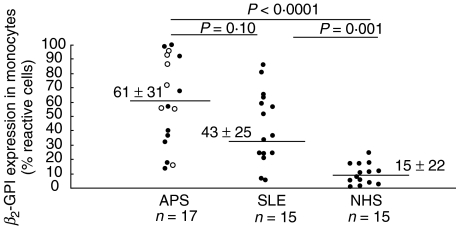

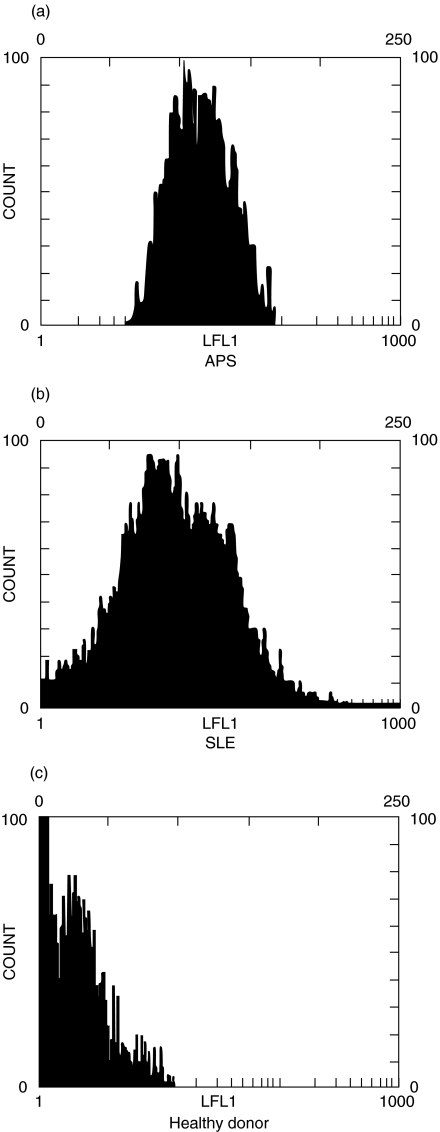

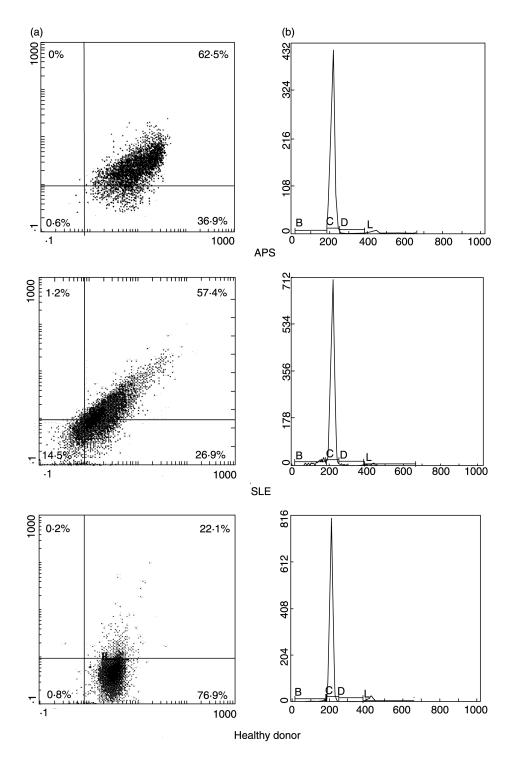

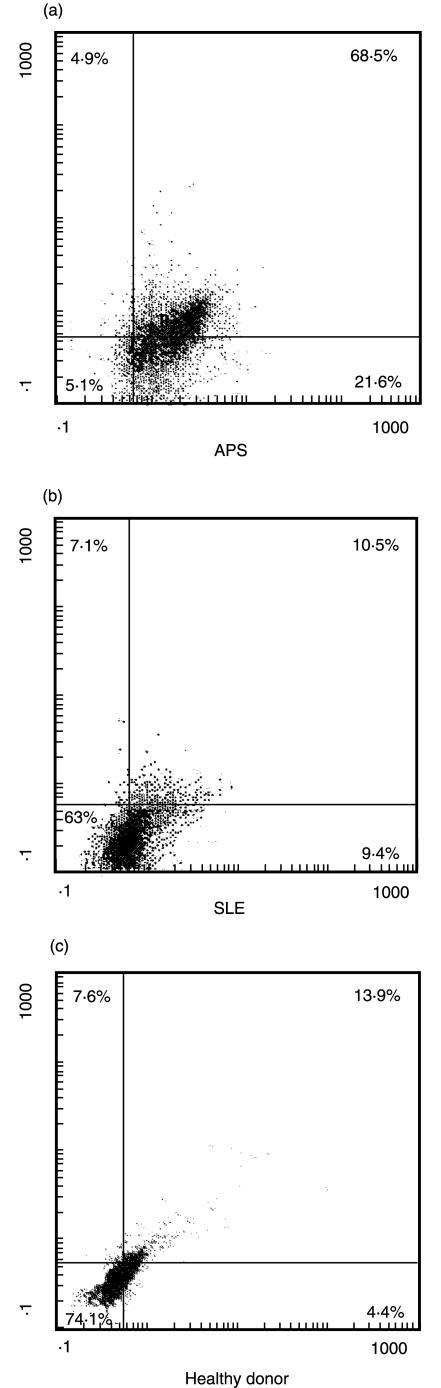

Cytofluorimetric analysis with anti-β2-GPI Ab showed a significantly higher staining for β2-GPI on monocytes from patients with APS (61 ± 31% reactive cells) or with SLE (43 ± 25) than from healthy donors (15 ± 22) (P < 0·0001 and P= 0·001, respectively) (Fig. 2). Although mean β2-GPI expression on monocytes from patients with APS was higher than that on monocytes from patients with SLE, this difference was not statistically significant (P = 0·104). In Fig. 3 a representative example of each group is reported. Similar findings were obtained using the anti-β2-GPI 1A4 MoAb (not shown). In order to confirm the expression of β2-GPI on a pure monocyte population we performed a double staining for CD14 and β2-GPI. Again, the cytofluorimetric analysis showed a significantly higher staining for β2-GPI on monocytes from patients with APS or with SLE than from healthy donors (P ≤ 0·001) (Fig. 4a). To rule out the possibility that the increased β2-GPI expression may be due to cell apoptosis, we analysed DNA fragmentation by cytofluorimetric analysis in the three groups under test. No significative hypodiploid peaks were detected (Fig. 4b) and virtually no difference was found between β2-GPI positive and negative cells (data not shown). In the analysis of the clinical data of individual patients, no significant correlation of monocyte β2-GPI expression with either occurrence of venous and/or arterial thrombosis and miscarriages or clinical activity of SLE was found. Moreover, no difference in β2-GPI expression of monocytes between primary and secondary APS was found. A double fluorescence was performed to assess whether the cell plasma membrane reactivity in APS and SLE patients was related to tissue factor expression on the cell surface. Monocytes were immunostained with anti-β2-GPI Ab, followed by PE-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG and then with FITC-conjugated anti-tissue factor MoAb. Dual staining showed that in patients with APS a very strong association between anti-tissue factor and anti-β2-GPI staining was observed (P < 0·001) (Fig. 5).

Fig. 2.

β2-GPI expression on human monocyte cell surface (% reactive cells), as detected by cytofluorimetric analysis. β2-GPI expression on monocytes from patients with APS (17 samples), 7 of which primary APS (○) and 10 secondary to SLE (•), patients with SLE (15 samples) and healthy donors (NHS) (15 samples) are shown. Means ± standard deviation.

Fig. 3.

Cytofluorimetric analysis of β2-GPI expression on human monocyte cell surface. The cells were stained with polyclonal anti-human β2-GPI. Dot plots (SSC/FSC) represent log fluorescence versus cell number, gated on cell population of a side scatter/forward scatter (SS/FS) histogram. Cell number is indicated on the y-axis and fluorescence intensity is represented in three logarithmic units at the x-axis. (a) β2-GPI expression on monocytes from a patient with APS; (b) β2-GPI expression on monocytes from a patient with SLE; (c) β2-GPI expression on monocytes from a healthy donor.

Fig. 4.

(a) Cytofluorimetric analysis of CD14 and β2-GPI. Monocytes were stained with polyclonal anti-human β2GPI plus PE-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG and then counterstained with FITC-conjugated anti-CD14 MoAb. Dot plots (SSC/FSC) represent log fluorescence. Green (FITC) fluorescence is indicated on the x-axis and red fluorescence (PE) is represented on the y-axis. The line indicates the background autofluorescence: upper left panel: β2GPI+CD14- cells; upper right panel: β2GPI+CD14+ cells; lower left panel: β2GPI-CD14-; lower right panel: β2GPI-CD14+ cells. One example representative of all the patients under test. β2-GPI expression on monocytes from a patient with APS or SLE is significantly higher as compared to those from a healthy donor. (b) Cells were fixed with 70% ethanol and, after adding RNAse, were stained with propidium iodide. A subdiploid peak in flow cytometry histograms (cursor B) identifies DNA fragmentation as the typical nuclear change that defines apoptosis. Cursor C reveals the diploid peak, cursor D the hyperdiploid peak and cursor L the tetraploid peak. Cell number is indicated on the y-axis and fluorescence intensity is represented at the x-axis. The cytofluorimetric analysis of DNA staining with propidium iodide showed a subdiploid peak of fluorescence of 2·6% for the patient with APS, 7·0% for the patient with SLE and 1·6% for the healthy donor. One example representative of all the subjects under test.

Fig. 5.

Cytofluorimetric analysis of tissue factor expression in anti-β2-GPI positive cells. Monocytes were stained with polyclonal anti-human β2GPI plus PE-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG and then counterstained with FITC-conjugated anti-tissue factor MoAb. Dot plots (SSC/FSC) represent log fluorescence. Green (FITC) fluorescence is indicated on the x-axis and red fluorescence (PE) is represented on the y-axis. The line indicates the background autofluorescence: upper left: β2GPI+TF- cells; upper right: β2GPI+TF+ cells; lower left: β2GPI-TF-; lower right: β2GPI-TF+ cells. (a) monocytes from a patient with APS; (b) monocytes from a patient with SLE; (c) monocytes from a healthy donor. In monocytes obtained from APS patients a very strong association between the two staining was observed (β2GPI+TF+ cells: 68·5%versus β2GPI+TF- cells: 4·9% and β2GPI-TF+ cells: 21·6%; P < 0·001). One example representative of all the patients under test.

Serum concentration of β2-GPI and anti-β2-GPI antibodies

In order to assess whether β2-GPI serum concentration or the presence of anti-β2-GPI antibodies were related to β2-GPI expression on monocyte surface, we firstly analysed β2-GPI serum concentration in all the patients. Serum β2-GPI concentration was 247 ± 155 mg/l in patients with APS, 384 ± 241 mg/l in patients with SLE and 224 ± 179 mg/l in healthy donors (SLE versus NHS p = 0·014; SLE versus APS NS; APS versus NHS NS). No significant differences were observed between primary and secondary APS. Moreover, no significant correlation between β2-GPI serum levels and monocyte β2-GPI surface expression was found. No significant correlation between the presence of aCl or anti-β2-GPI antibodies and β2-GPI monocyte surface expression was observed. A significant association between aCl IgG and anti-β2-GPI IgG was found (P < 0·01).

DISCUSSION

This investigation demonstrates β2-GPI mRNA expression by human monocytes, thus indicating that these cells synthesize β2-GPI. In addition, we show that β2-GPI expression on monocytes is increased in patients with APS and SLE and correlates with tissue factor expression.

The demonstration of β2-GPI mRNA in human monocytes by RT-PCR extends the knowledge that the liver [9,24] is not the exclusive site of β2-GPI synthesis [10,11]. In this concern, the production of β2-GPI mRNA has been previously demonstrated, in endothelial cells, astrocytes, neurones and lymphocytes [12]. These findings support the view that β2-GPI can have not only extracellular but also intracellular origin. This hypothesis is further supported by the observation that in endothelial cells β2-GPI is located and accumulates in late endosomes [25,26]. Interestingly, β2-GPI expression on monocytes is significantly increased in patients with APS or SLE as compared to healthy donors. On the basis of this finding, together with the observation that β2-GPI is detectable on monocytes even after the withdrawal of serum from cell culture, it is possible to hypothesize that β2-GPI synthesis is increased in monocytes from APS or SLE patients. However, it is certainly possible that β2-GPI was present on the cells when they were isolated from plasma and was not removed by short-term colture in serum-free medium or that it comes from β2-GPI secreted by the cultured cells.

Anyway, the observation of increased β2-GPI expression on monocytes could have relevant implications in the immunopathogenesis of the APS, given that monocytes might play a role in the thrombogenesis associated with APS [16,17]. Indeed, circulating monocytes of patients with primary APS display tissue factor overexpression that may contribute to the prothrombotic state [27]. Stimulation of peripheral blood mononuclear cells of these patients with β2-GPI induces substantial monocyte tissue factor, which was shown to be dose-dependent and requiring CD4+ T lymphocytes and class II MHC molecules to be expressed [28]. These findings suggested that patients with APS may have chronic stimulation of β2-GPI-specific T lymphocytes which leads to persistently high monocyte tissue factor expression and consequently to a prothrombotic diathesis [28]. This hypothesis is in keeping with our observation that β2-GPI expression on monocyte plasma membrane of APS patients is closely related to tissue factor expression. Although we did not demonstrate a significant association between β2-GPI expression on monocytes and the clinical manifestations of the syndrome, only a follow-up study, including subjects with active thrombosis, could disclose the predictive meaning of this finding. In conclusion, the demonstration of β2-GPI synthesis by human monocytes confirms and extends the possibility that different cell types are able to synthesize this protein, as recently suggested by the identification of β2-GPI in late endosomes of endothelial cells [25,26]. In addition, these results indicate that β2-GPI on monocyte surface offers a physiopathologically relevant target for anti-β2-GPI antibodies, thus providing new mechanistic insights into APS pathogenesis.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hughes GRV. The anticardiolipin syndrome. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 1985;3:285–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hughes GRV, Harris EN, Gharavi AE. The anticardiolipin syndrome. J Rheumatol. 1986;13:486–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilson WA, Gharavi AE, Koike T, et al. International consensus statement on preliminary classification criteria for definite antiphospholipid syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42:1309–11. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199907)42:7<1309::AID-ANR1>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Galli M, Confurius P, Maassen C, et al. Anticardiolipin antibodies (ACA) directed not to cardiolipin but to a plasma protein cofactor. Lancet. 1990;355:1544–7. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)91374-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hunt J, Krilis S. The fifth domain of β2-glycoprotein I contains a phospholipid binding site (Cys 281-Cys 288) and a region recognized by anticardiolipin antibodies. J Immunol. 1994;152:653–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sorice M, Circella A, Griggi T, et al. Anticardiolipin and anti-β2-GPI are two distinct populations of autoantibodies. Thromb Haemost. 1996;75:303–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tsutsumi A, Matsuura E, Ichikawa K, Fujisaku A, Mukai M, Kobayashi S, Koike T. Antibodies to beta 2-glycoprotein I and clinical manifestation in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1996;39:1466–74. doi: 10.1002/art.1780390905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kornberg A, Renaudineau Y, Blanche M, Jouinou P, Shoenfeld Y. Anti-Beta2-Glycoprotein I antibodies and Anti-Endothelial Cell Antibodies Induce Tissue Factor in Endothelial Cells. IMAJ. 2000;2:27–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Day JR, O'Hara PJ, Grant FJ, Lofton-Day C, Berkaw MN, Werner P, Arnaud P. Molecular cloning and sequence analysis of the cDNA encoding human apolipoprotein H (beta2-glycoprotein I) Int J Clin Lab Res. 1992;21:256–63. doi: 10.1007/BF02591656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Avery VM, Adrian DL, Gordon DL. Detection of mosaic protein mRNA in human astrocytes. Immunol Cell Biol. 1993;71:215–9. doi: 10.1038/icb.1993.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chamley LW, Allen JL, Johnson PM. Synthesis of β2 glycoprotein I by the human placenta. Placenta. 1997;18:403–10. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4004(97)80040-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Caronti B, Calderaro C, Alessandri C, Conti F, Tincani R, Palladini G, Valesini G. β2-glycoprotein I (β2GPI) mRNA is expressed by several cell types involved in antiphospholipid syndrome-related tissue damage. Clin Exp Immunol. 1999;115:214–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1999.00770.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Caronti B, Pittoni V, Palladini G, et al. Anti β2-glycoprotein I antibodies bind to central nervous system. J Neurol Sci. 1998;156:211–9. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(98)00027-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mackman N, Morrissey JH, Fowler B, Edgington TS. Complete sequence of the human tissue factor gene, a highly regulated cellular receptor that initiates the coagulation protease cascade. Biochemistry. 1989;28:1755–62. doi: 10.1021/bi00430a050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kornberg A, Blank M, Kaufman S, Shoenfeld Y. Induction of tissue factor-like activity in monocytes by anticardiolipin antibodies. J Immunol. 1994;153:1328–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cuadraro MJ, Lòpez-Pedrera C, Khamashta MA, Camps MT, Tinahones F, Torre A, Hughes GRV, Velasco F. Thrombosis in primary antiphospholipid syndrome. A pivotal role for monocyte tissue factor expression. Arhritis Rheum. 1997;40:834–41. doi: 10.1002/art.1780400509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Amengual O, Atsumi T, Khamashta MA, Hughes GRV. The role of Tissue Factor pathway in ipercoagulable state in patients with Antiphospholipid Syndrome. Thromb Haemost. 1998;79:276–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hochberg MC. Updating the American College of Rheumatology revised criteria for the classification of SLE. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40:1725. doi: 10.1002/art.1780400928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coligan JE, Kruisbeek AM, Margulies DH, Shevach EM, Strober W. Isolation of Monocyte/Macrophage Populations. In: John Wiley & Sons, editor. Current Protocols in Immunology. New York: Greene Publishing Associates and Wiley-Interscience; 1991. pp. 7.6.1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Steinkasserer A, Estaller C, Weiss EH, et al. Complete nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequence of human beta-2 glycoprotein I. Biochem J. 1991;277:387–91. doi: 10.1042/bj2770387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cusimano G, Palladini G, Lauro GM. MHC class II expression by human glioma cells after in vitro incubation with soluble antigens. Acta Neurol Scand. 1990;81:215–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1990.tb00969.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ponte P, Ng SY, Engel J, Gunning P, Kedes L. Evolutionary conservation in the untraslated regions of actin cDNA. Nucl Acid Res. 1984;12:1687–96. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.3.1687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kamboh MI, Manzi S, Mehdi H, Fitzgerald S, Sanghera DK, Kuller LH, Aston CE. Genetic variation in apolipoprotein H (β2-glycoprotein I) affects the occurrence of antiphospholipid antibodies and apolipoprotein H concentrations in systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 1999;8:742–50. doi: 10.1191/096120399678840909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matsuura E, Igarashi M, Igarashi Y, Nagae H, Ichikawa K, Yasuda T, Koike T. Molecular definition of human beta 2-glycoprotein I (beta 2-GPI) by cDNA cloning and inter-species differences of beta 2-GPI in alternation of anticardiolipin binding. Int Immunol. 1991;3:1217–21. doi: 10.1093/intimm/3.12.1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dunoyer-Geindre S, Kruithof EKO, Galbe-de Rochemonteix B, Rosnoblet C, Gruenberg J, Reber G, de Moerloose P. Localization of β2 glycoprotein I in late endosomes of human endothelial cells. Thromb Haemost. 2001;85:903–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sorice M, Ferro D, Misasi R, et al. Evidence for anticoagulant activity and β2-GPI accumulation in late endosomes of endothelial cells induced by anti-LBPA antibodies. Thromb Haemost. 2002;87:735–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dobado-Berrios PM, Lopez-Pedrera C, Velasco F, Aguirre MA, Torres A, Cuadrado MJ. Increased levels of Tissue Factor mRNA in mononuclear blood cells of patients with Primary Antiphospholipid Syndrome. Thromb Haemost. 1999;82:1578–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Visvanathan S, Geczy CL, Harmer JA, McNeil HP. Monocyte Tissue Factor induction by activation of β2-glycoprotein-I-specific T lymphocytes is associated with thrombosis and fetal loss in patients with antiphospholipid antibodies. J Immunol. 2000;165:2258–62. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.4.2258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]