Abstract

The identification of immunodominant and universal mycobacterial peptides could be applied to vaccine design and have an employment as diagnostic reagents. In this paper we have investigated the fine specificity, clonal composition and HLA class II restriction of CD4+ T cell clones specific for an immunodominant epitope spanning amino acids 91–110 of the 16-kDa protein of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Twenty-one of the tested 28 clones had a Th1 profile, while seven clones had a Th0 profile. None of the clones had a Th2 profile. While the TCR AV gene usage of the clones was heterogeneous, a dominant TCR BV2 gene family was used by 18 of the 28 clones. The CDR3 regions of BV2+ T cell clones showed variation in lengths, but a putative common motif R-L/V-G/S-Y/W-E/D was detected in 13 of the 18 clones. Moreover, the last two to three residues of the putative CDR3 loops, encoded by conserved BJ sequences, could also play a role in peptide recognition. Antibody blockade and fine restriction analysis using HLA-DR homozygous antigen-presenting cells established that 16 of 18 BV2+ peptide-specific clones were DR restricted and two clones were DR-DQ and DR-DP restricted. Additionally, five of the 18 TCRBV2+ clones recognized peptide 91–110 in association with both parental and diverse HLA-DR molecules, indicating their promiscuous recognition pattern. The ability of peptide 91–110 to bind a wide range of HLA-DR molecules, and to stimulate a Th1-type interferon (IFN)-γ response more readily, encourage the use of this peptide as a subunit vaccine component.

Keywords: CD4+ T cells, HLA restriction, IFN-γ, 16-kDa M. tuberculosis antigen, T cell receptor

INTRODUCTION

The resurgence of tuberculosis worldwide has intensified research efforts directed at examining the host defence and pathogenic mechanisms operative in Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. M. tuberculosis, the primary aetiological agent of tuberculosis, causes approximately 8 million new cases each year and the disease is responsible for at least 3 million deaths annually [1]. M. tuberculosis is a classical example of a pathogen for which the protective response relies on cell-mediated immunity. Several studies have demonstrated that cellular immunity mediated by interferon (IFN)-γ-secreting CD4+ T cells plays a critical role in the protective response against M. tuberculosis. In fact, the primary effector function of CD4+ T cells is believed to be production of IFN-γ and possibly other cytokines, sufficient to activate macrophage, which can then control or eliminate intracellular organisms [1].

Peptide subunit vaccines have hitherto been considered unlikely vaccine candidates because of allele-specific binding to HLA class II molecules, thus potentially necessitating the definition and use of a large number of antigenic peptides to achieve adequate vaccine coverage in an outbreed population. However, the peptide binding requirements for HLA class II molecules are less restricted and this has led to definition of a certain number of peptides from M. tuberculosis able to bind with high affinity to more than one HLA class II molecule.

The 16-kDa α-crystallin (acr) antigen of M. tuberculosis might represent a good antigenic target of protective T cell responses. This protein is expressed predominantly by M. tuberculosis during stationary growth or subjected to oxygen deprivation, and can account for up 25% total bacillary protein expression in these circumstances. Accordingly, increased expression of the 16-kDa gene has been detected in M. tuberculosis-infected mice as well as in lung biopsies from tuberculous (TB) patients with chronic cavitary lesions. As containment within the granuloma may induce similar conditions, the 16-kDa protein might be an important antigenic target during bacillary latency [2]. Additionally, we have found that post-chemotherapy changes in T cell proliferative and IFN-γ responses in TB patients are particularly striking for T cells recognizing the 16-kDa antigen. Finally, the 16-kDa antigen contains an immunodominant and genetically permissive epitope, spanning amino acids 91–110, which should represent a candidate subunit vaccine component [3–5].

We have developed recently a number of CD4+ T cell clones from the peripheral blood and body fluids of patients affected by different clinical forms of tuberculosis, by polyclonal stimulation in vitro with phytohaemoagglutinin (PHA) and interleukin 2 (IL-2). Among these clones, 55 were found to recognize the 16-kDa protein and 28 of the latter recognized its 91–110 epitope, thus supporting its immunodominance also at a clonal level.

In this study we have investigated the fine specificity, clonal composition, and HLA class II restriction of CD4+ T cell clones specific for the 91–110 epitope of the 16-kDa protein of M. tuberculosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

Peripheral blood and body fluids were obtained from six TB patients before the onset and 4 months after antituberculous therapy. Two patients were affected by TB pleuritis, one by TB ascitis, one by effusive TB pericarditis and the last two by TB meningitis. The baseline characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 1. The clinical diagnosis was confirmed by ultrasound, CT scanning and symptomatic improvement following antituberculous chemotherapy. Mtb was detected by culture and by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) in both cerebrospinal fluids (CSF) samples (patients 5 and 6), in pleural fluid sample (patient 2) and in ascitic fluid sample (patient 3). All six patients had a negative tuberculin-PPD skin test with <5 mm skin induration at 48–72 h after injection of 1 U of PPD (Statens Seruminstitut, Copenaghen, Denmark).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of TB patients

| Patient no. | Diagnosis | Disease status | PPD status |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | TB pleuritis | Active | Negative |

| 2 | TB pleuritis | Active | Negative |

| 3 | TB ascitis | Active | Negative |

| 4 | TB pericarditis | Active | Negative |

| 5 | TB meningitis | Active | Negative |

| 6 | TB meningitis | Active | Negative |

None of the patients had evidence of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, nor were treated with steroids or antitubercular drugs at the time of first sampling. Informed consent was obtained from the patient or their parents.

TB patients were HLA-typed serologically and in some cases the HLA antigens were confirmed by PCR amplification technique using sequence-specific oligonucleotide primers.

Generation of CD4+ T cell clones

Generation of CD4+ T cell clones from the peripheral blood and body fluids of patients affected by different clinical forms of tuberculosis has been described in detail [3].

Briefly, CD4+ T lymphocytes were isolated from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) or diseased body fluids by immunomagnetic sorting, using an anti-CD4 specific MoAb (MEM-115, a kind gift of Prof. Vaclav Horejsi, Institute of Molecular Genetics, Academy of Science of the Czech Republic, Prague, Czech Republic) and cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated pooled human AB serum. Wells of U-bottomed 96-well plates (Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark) were seeded with 104 CD4+ T cells, 2 × 105 allogeneic PBMC (irradiated 3000 rads from a caesium source), 5 × 104 irradiated autologous Epstein–Barr virus-transformed homozygous lymphoblastoid B (EBV-B) cells, 0·5 µg/ml PHA (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) and 200 U/ml human recombinant IL-2 (Genzyme, Cambridge, MA, USA) in a total volume of 0·2 ml. After 21 days of culture, the cells were transferred to tissue-culture flasks and expanded further in the presence of 200 U IL-2 ml. The cell lines were 92–98% CD4+ by FACS analysis. Cloning at 0·3 cells/well in the medium supplemented as in the initial cell culture yielded at 40–100% plating efficiency. The average frequency of positive wells was approximately 15%, which corresponds to an estimated growth frequency of 60% under limiting dilution conditions, following a single-hit Poisson distribution (data not shown). T cell clones were used for assay at least 3 days after the last IL-2 addition. This cloning procedure, using PHA and allogeneic stimulation, induces the expansion of virtually all CD4+ T cells and does not introduce any bias in the T cell repertoire [3,6].

Synthetic peptides and cell lines

Peptide 91–110 derived from the sequence of the 16-kDa protein of M. tuberculosis was prepared using solid-phase/Fmoc chemistry as described in detail elsewhere. The peptide was of 90% purity and its homogeneity was confirmed by analytical reverse phase HPLC, mass spectroscopy and amino acid composition analysis. The sequence of peptide 91–110 is the following: SEFAYGSFVRTVSLPVGADE.

Epstein–Barr virus-transformed homozygous lymphoblastoid B (EBV-B) cell lines were obtained from Istituto Tumori Genova (IST, Genova, Italy).

In vitro stimulation of peptide-specific CD4+ T cells and cytokines assays

CD4+ T cells were washed twice in RPMI-1640 medium to remove excess IL-2; 5 × 104 T cells/well were incubated with irradiated (30 Gy) autologous or allogeneic EBV-B cells (15 × 104) in the presence of synthetic peptides at different concentrations. After 24 h the supernatants were collected and stored at −70°C until tested. IFN-γ and IL-4 contents were assessed by a two-MoAb sandwich ELISA kit, according to the manufacturer's recommendations (Euroclone, Devon, UK).

Determination of HLA restriction and inhibition studies

CD4+ T cells were incubated as described above, with peptides and irradiated homozygous EBV-B cells expressing different HLA-DR molecules. Control cultures consisted of the T cell clones alone and T cell clones incubated with EBV-B without peptide.

For inhibition studies, autologous APCs were preincubated with HLA-specific MoAbs for 1 h at 37°C, followed by addition of the T cells and peptides. Murine MoAbs against human MHC class II determinants, L243 (anti HLA-DR, IgG2a), Leu 10 (anti-HLA-DQ, IgG1) and B7/21 (anti-HLA-DP, IgG1) were purchased from Becton Dickinson (Mountain View, CA, USA) and used at a final concentration of 10 µg/ml. Isotype-control MoAbs were used at the same concentration.

Analysis of TCR-BV and -AV gene usage, amplification and sequencing of TCR transcripts

CD4+ T cell clones were restimulated and 14 days later 5 × 106 T cells were harvested. After this time interval, the irradiated lymphocytes are no longer present and thus do not interfere with TCR-BV analysis, as ascertained in preliminary experiments.

Total RNA was extracted from 2 to 5 × 105 T cell clones by the single-step acid guanidinium thiocyanate method described by Chomczynski & Sacchi [7]. Reverse transcription of RNA was performed using a cDNA synthesis kit (Applied Biosystems, Rome, Italy). Amplification of TCR.

AV and BV regions was performed using PCR primers specific for the constant region and variable domains of the TCR (Immuno Source, Los Altos, CA, USA), which allow amplification of 21 BV (BV1–12, BV13S1 and BV13S2, BV14 to BV20) and 19 AV (AV1 to AV18, AV22) families. Each PCR contained 0·5 mm of each primer, 2 µl cDNA, 0·2 m dNTPs, 2 U Taq polymerase (Applied Biosystems), 10 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8), 50 mm KCl and 1·5 mm MgCl2 in a final volume of 50 µl. The reaction was run for 35 cycles of 1 min denaturation at 95°C, 1 min annealing at 55°C and 1 min extension at 72°C. Ten per cent of each PCR reaction was analysed in a 2% agarose gel and amplified products were assessed by ethidium bromide staining.

Sequencing of BV2 junctions was performed directly (i.e. without prior bacterial cloning) on T cell clones-derived cDNA, amplified using pairs of BC primer (5′–GGG AGA TCT CTG CTT CTG ATG GCT C−3′) and BV2-specific primer (5′–ACA TAC GAG CAA GGC GTC GAG AAG G−3′), as described in [6], using Sequenase (Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden).

RESULTS

Cytokine profile of 16-kDa peptide 91–110-specific CD4+ T cell clones

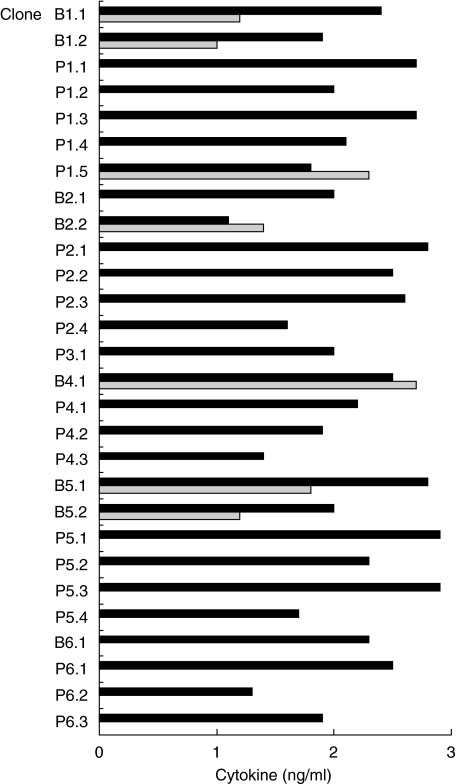

We have reported previously that 28 CD4+ T cell clones derived from the peripheral blood or disease sites of six TB patients, upon polyclonal stimulation with PHA and IL-2, recognize the 16-kDa acr protein of M. tuberculosis and its 91–110 epitope [3]. Of note, all the 16-kDa-reactive CD4+ T cell clones obtained from body fluids were originated before chemotherapy, while those obtained from peripheral blood originated 4 months after chemotherapy. These clones are signed with the letter B (body fluid) and P (peripheral blood), respectively. As shown in Fig. 1, 21 of the 28 clones had a Th1 profile as they produced IFN-γ, but not IL-4, in response to peptide 91–110 and autologous antigen-presenting cells (APC), while seven clones had a Th0 profile as they produced both IFN-γ and IL-4. None of the clones had a Th2 profile. The cytokine-producing profile of the clones was irrespective of whether they were obtained from peripheral blood or from disease sites.

Fig. 1.

Cytokine production profile of peptide 91–110-specific CD4+ T cell clones. Twenty-eight CD4+ T cell clones derived from peripheral blood or disease sites of tuberculous patients were stimulated with peptide 91–110 in the presence of autologous APC. Supernatants were collected and IFN-γ (black bars) and IL-4 (grey bars) levels measured.

TCR AV and TCR BV gene usage of peptide 91–110-specific T cell clones

CD4+ T cell clones were analysed for TCR AV and BV gene usage by reverse transcription (RT)-PCR. As shown in Table 2, a dominant BV2 gene was expressed by 18 clones (64%). Three clones expressed BV8 while other clones had heterogeneous BV expression (BV3, 4, 5, 6, 12, 14 and 17). The corresponding AV genes were strikingly heterogeneous. With the exception of AV8, which was used by six of the 28 CD4+ T cell clones (21%), a total of 10 different AV families were expressed.

Table 2.

T cell receptor usage of peptide 91–110-specific CD4 T cell clones

| TCR usage | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient no. | HLA-DR | Clone no. | Clone derived from* | Clone phenotype | BV | AV |

| 1 | DR3/7 | B1·1 | Pleural fluid | Th0 | 2 | 8 |

| B1·2 | Pleural fluid | Th0 | 2 | 17 | ||

| P1·1 | Peripheral blood | Th1 | 2 | 2 | ||

| P1·2 | Peripheral blood | Th1 | 2 | 10 | ||

| P1·3 | Peripheral blood | Th1 | 2 | 17 | ||

| P1·4 | Peripheral blood | Th1 | 3 | 2 | ||

| P1·5 | Peripheral blood | Th0 | 8 | 12 | ||

| 2 | DR14/15 | B2·1 | Pleural fluid | Th1 | 2 | 1 |

| B2·2 | Pleural fluid | Th0 | 6 | 10 | ||

| P2·1 | Peripheral blood | Th1 | 2 | 17 | ||

| P2·2 | Peripheral blood | Th1 | 2 | 1 | ||

| P2·3 | Peripheral blood | Th1 | 5 | 6 | ||

| P2·4 | Peripheral blood | Th1 | 8 | 2 | ||

| 3 | DR1/15 | P3·1 | Peripheral blood | Th1 | 2 | 8 |

| 4 | DR4/13 | B4·1 | Pericardic fluid | Th0 | 2 | 10 |

| P4·1 | Peripheral blood | Th1 | 2 | 8 | ||

| P4·2 | Peripheral blood | Th1 | 2 | 8 | ||

| P4·3 | Peripheral blood | Th1 | 12 | 22 | ||

| 5 | DR5/7 | B5·1 | Cerebrospinal fluid | Th0 | 2 | 12 |

| B5·2 | Cerebrospinal fluid | Th0 | 17 | 18 | ||

| P5·1 | Peripheral blood | Th1 | 2 | 17 | ||

| P5·2 | Peripheral blood | Th1 | 2 | 1 | ||

| P5·3 | Peripheral blood | Th1 | 2 | 10 | ||

| P5·4 | Peripheral blood | Th1 | 4 | 17 | ||

| 6 | DR1/5 | B6·1 | Cerebrospinal fluid | Th1 | 8 | 8 |

| P6·1 | Peripheral blood | Th1 | 2 | 8 | ||

| P6·2 | Peripheral blood | Th1 | 2 | 2 | ||

| P6·3 | Peripheral blood | Th1 | 14 | 5 | ||

T cell clones were obtained from different body fluids before therapy or from peripheral blood 4 months after therapy.

Comparison of CDR3 region sequences of peptide 91–110-specific BV2+ T cell clones

Because of the predominant BV2 gene usage by peptide 91–110-specific CD4+ T cell clones, further analysis involved only such clones.

The CDR3 regions of BV2+ T cell clones were analysed and their sequences were compared in order to identify a conserved motif in the CDR3 regions of TCRs with the same epitope specificity.

Ten different BJ segments were used by the TCRs of the 18 clones, the most frequent of which were BJ2·1 and BJ2·7, both expressed in three clones (Table 3). We did not notice any particular selection of BJ sequences that correlated with HLA-DR restriction. The large BJ repertoire and additional junctional due to imprecise joining and N-region addition was reflected in the highly heterogeneous BV CDR3 regions (Table 3). In general, there was a variation in lengths of the BV2 CDR3 regions that ranged from six to nine amino acids (Table 3). The residues from BJ regions contributing to CDR3 are underlined. The last two to three residues of the putative CDR3 loops, encoded by the BJ sequence, are normally conserved in their respective J segments, suggesting that their role is probably to help maintain the overall conformation of the CDR3 loops rather than to contact ligand directly [9,10]. Despite the heterogeneity of BV and BJ segments used, certain conserved amino acid sequences were identified in the CDR3 region [11]. A putative common motif R-L/V-G/S-Y/W-E/D, or at least part of it (highlighted in bold in Table 3), is apparent in 13 of the 18 clones, being absent in clones P2·1, B4·1, B5·1, P5·3 and P6·1.

Table 3.

. CDR3 region analysis of BV2+ peptide 91–110-specific CD4+ T cell clones

| Junctional sequence | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient no. | Clone | BV | CDR3 | BJ |

| 1 | B1·1 | 2 | SRLGYSNEQ | 2·1 |

| B1·2 | 2 | PYSIYDTQ | 2·3 | |

| P1·1 | 2 | AALGYKDTQ | 2·3 | |

| P1·2 | 2 | SSRGYLETQ | 2·5 | |

| P1·3 | 2 | LVGEGYEQ | 2·7 | |

| 2 | B2·1 | 2 | LVGYEQ | 2·7 |

| P2·1 | 2 | GADNEK | 1·4 | |

| P2·2 | 2 | TVSDGYGY | 1·2 | |

| 3 | P3·1 | 2 | LDLGKANEQ | 2·1 |

| 4 | B4·1 | 2 | PTGTPQPQ | 1·5 |

| P4·1 | 2 | LYLGVSYEQ | 2·7 | |

| P4·2 | 2 | DRGLYNTEA | 1·1 | |

| 5 | B5·1 | 2 | LDNYRTEA | 1·1 |

| P5·1 | 2 | SRWDYEQ | 2·1 | |

| P5·2 | 2 | GSSYPQ | 1·5 | |

| P5·3 | 2 | FTWPGGEL | 2·2 | |

| 6 | P6·1 | 2 | SGTPETETQ | 2·5 |

| P6·2 | 2 | RLYTGNTI | 1·3 | |

Amino acid residues are indicated using a single-letter code. The last two–three residues of putative CDR3 loops, encoded by the BJ sequence, are normally conserved in their respective J segments and are underlined. Common motif residues are highlighted in bold.

HLA restriction

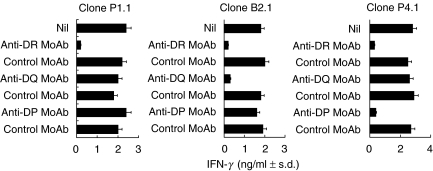

HLA class II restriction of individual clones was determined by testing the ability of DR-, DQ- or DP-specific antibodies to inhibit IFN-γ production in response to peptide 91–110 and autologous APCs [12]. The results (Table 4) indicate that IFN-γ production could be blocked in all tested clones by the anti-HLA-DR MoAb. Moreover, stimulation of two clones could be blocked by a simultaneous presence of anti-DP/anti-DR (clone P4·1) and anti-DQ/anti-DR antibodies (clone B2·1), indicating that these two clones actually recognize peptide 91–110 presented in the context of both HLA-DR and -DQ/DP molecules. Figure 2 shows primary inhibition data of the P4·1 and B2·1 clones, as well as a representative HLA-DR-restricted clone, P1·1.

Table 4.

Inhibition of peptide 91–110 CD4 T cell clones by anti-HLA class II MoAbs

| Patient no. | HLA-DR phenotype | Clone no. | Clone phenotype | HLA restriction molecule |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | DR3/7 | B1·1 | Th0 | DR |

| B1·2 | Th0 | DR | ||

| P1·1 | Th1 | DR | ||

| P1·2 | Th1 | DR | ||

| P1·3 | Th1 | DR | ||

| 2 | DR14/15 | B2·1 | Th1 | DR/DQ |

| P2·1 | Th1 | DR | ||

| P2·2 | Th1 | DR | ||

| 3 | DR1/15 | P3·1 | Th1 | DR |

| 4 | DR4/13 | B4·1 | Th0 | DR |

| P4·1 | Th1 | DR/DP | ||

| P4·2 | Th1 | DR | ||

| 5 | DR11/7 | B5·1 | Th0 | DR |

| P5·1 | Th1 | DR | ||

| P5·2 | Th1 | DR | ||

| P5·3 | Th1 | DR | ||

| 6 | DR1/11 | P6·1 | Th1 | DR |

| P6·2 | Th1 | DR |

CD4+ T cells were cultured in the presence of peptide 91–110 and autologous APCs pre-incubated with HLA-specific MoAbs L243 (anti-HLA-DR, IgG2a), Leu 10 (anti-DQ, IgG1) and B7/21 (anti-HLA-DP, IgG1).

Fig. 2.

HLA class II restriction of peptide 91–110-specific CD4+ T cell clones. T cells were cultured for 72 h as described in Materials and Methods. HLA class II blocking and isotype-matched control antibodies were added to cultures to establish the MHC restriction. After 48 h supernatant was collected and assayed for IFN-γ content by ELISA.

To identify the HLA-DR molecules involved in the peptide presentation, T cell clones were tested for IFN-γ production to peptide 91–110 in the presence of HLA-DR homozygous matched EBV-B cells as APC. The results are shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

HLA restriction of peptide 91–110 specific CD4+ BV2+ T cell clones

| Patient no. | HLA-DR phenotype | Clone no. | Clone phenotype | HLA restriction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | DR3/7 | B1·1 | Th0 | DR7 |

| B1·2 | Th0 | DR7 | ||

| P1·1 | Th1 | DR7 | ||

| P1·2 | Th1 | DR7 | ||

| P1·3 | Th1 | DR7 | ||

| 2 | DR14/15 | B2·1 | Th1 | DR15 |

| P2·1 | Th1 | DR14, DR15, DR11 | ||

| 2·2 | Th1 | DR14 | ||

| 3 | DR1/15 | P3·1 | Th1 | DR1, DR15 |

| 4 | DR4/13 | B4·1 | Th0 | DR4, DR13, DR11, DR14 |

| P4·1 | Th1 | DR4, DR13, DR11, DR14 | ||

| P4·2 | Th1 | DR13 | ||

| 5 | DR11/7 | B5·1 | Th0 | DR7, DR11, DR12, DR13 |

| P5·1 | Th1 | DR7, DR11 | ||

| 5·2 | Th1 | DR11 | ||

| 5·3 | Th1 | DR7, DR11 | ||

| 6 | DR1/11 | P6·1 | Th1 | DR11, DR12, DR13 |

| P6·2 | Th1 | DR1, DR11 |

HLA-DR restriction of CD4+ T cell clones that recognize peptide 91–110 in the context of either parental or allogeneic HLA-DR molecules are underlined.

Thirteen of 18 BV2 T cell clones (72,2%) recognize peptide 91–110 exclusively when presented by one or both parental HLA-DR molecules, while five of 18 clones (27,8%) recognize peptide 91–110 in the context of either parental or allogeneic HLA-DR molecules, indicating a promiscuous recognition (Table 5).

DISCUSSION

T cell recognition of proteins involves binding of distinct peptide regions to the polymorphic, allele-specific domains of MHC molecules [13–16]. The diversity of immunodominant sequences recognized in the context of the widely polymorphic HLA genotypes in man represents an inherent obstacle for the development of synthetic peptides as potential diagnostic tools or vaccine subunits. Therefore, a special interest is attached to promiscuous, immunodominant peptides, which have been identified in several microbial antigens, endogenous proteins and potential autoantigens. A better understanding of structural features of immunogenic peptides in relation to multiple HLA-DR alleles is necessary for the rational design of permissively recognized variant peptides of biological interest.

In this paper, we have studied the cytokine production, HLA restriction and the TCR repertoire of CD4+ T cell clones specific for peptide 91–110 of the 16-kDa protein of M. tuberculosis.

In our study, 21 of 28 peptide 91–110-reactive CD4+ T cell clones had a Th1 profile as they produced IFN-γ, but not IL-4, in response to peptide 91–110 and autologous APC, while seven clones had a Th0 profile as they produced both IFN-γ and IL-4. None of the clones had a Th2 profile. The cytokine-producing profile of the clones was irrespective of whether they were obtained from peripheral blood or from disease sites [3]. The ability of the clones to produce IFN-γ provides a mechanism by which this T cell subset might contribute to immunity against M. tuberculosis infection. In fact, IFN-γ synergizes with other cytokines for induction of inducible nitric oxide synthase and production of nitric oxide from macrophages which, in turn, exert cytocidal effects on intracellular bacteria such as M. tuberculosis.

By the use of monoclonal antibody blocking studies and HLA-matched homozygous EBV-B cells as peptide-presenting cells, we have demonstrated that the phenotype of response is in the vast majority of clones related to the presenting HLA-DR molecule. This was true for all tested clones, with the exception of clone B2·1, whose response was inhibited by antibodies to HLA-DR and HLA-DQ molecules, and clone P4·1, whose response was inhibited by antibodies to HLA-DR and HLA-DP molecules. Fine HLA-DR restriction of the clones was confirmed by analysing their response upon in vitro stimulation with peptide 91–110 and homozygous EBV-B cells as antigen-presenting cells. Of the 18 clones tested, nine clones recognized 91–110 in the context of only one parental HLA-DR molecule, four clones recognized peptide 91–110 in the context of both parental HLA-DR molecules and five clones recognized peptide 91–110 in the context of both parental and completely allogeneic molecules, indicating their promiscuous nature. Although in all these cases the allogeneic HLA-DR molecules share the same HLA-B3 gene product (i.e. HLA-DR52), the latter does not seem to be the true restriction element, as stimulation of clones occurred in the presence of only some, but not all EBV-B cell lines expressing the B3 alleles. This indicates that the promiscuous recognition pattern of some peptide 91–110-specific T cell clones should be the consequence of the binding of the peptide to certain conserved sequences of certain HLA-DR molecules. Further analysis on the identification of the precise HLA-DR alleles that restrict presentation of peptide 91–110 to T cell clones and comparison of their amino acid sequences might help to define the nature of the promiscuity of some clones.

Analysis of TCR α and β chain expression of the 28 peptide 91–110-specific CD4+ T cell clones revealed diversity in V segments in both chains. A particular BV gene product, BV2, was used preferentially by peptide 91–110-specific CD4+ T cell clones, irrespective of the HLA-DR molecule presenting the peptide. Thus, consistent with previously published results, the HLA class II molecule is not required for shared BV gene usage by TCRs specific for this peptide. In the antipeptide 91–110 response no preferential usage of other BV gene was found in a series of clones not expressing BV2, suggesting that the latter is strongly selected, at least in individuals studied, for interaction with a structural determinant common to the different peptide/HLA-DR complexes recognized. However, further studies are needed to clarify whether the determinant selecting BV2 is borne by the non-polymorphic DR α chain or a common motif of the polymorphic DR β chain, or rather of the peptide, or both the peptide and the DR molecule.

The TCR BV usage in the 28 clones tested was not biased to only one AV gene, as observed for BV. For instance, if we consider the 18 clones using BV2, seven different AV genes were used to recognize peptide 91–110, without any apparent predominant AV usage. AV usage by non-BV2 clones was even more diverse, with nine different AV genes used by the 10 non-BV2 T cell clones. However, due to the low number of clones available, it was not possible to compare the significance of these differences. The most striking finding of this study came from the analysis of the V-J CDR3 regions of the β chain of BV2 positive clones. Despite the fact that the β chain junctional regions appeared to be diverse in both length and amino acid composition, a common motif was observed. The sequence R-L/V-G/S-Y/W-E/D (or at least part of it) was apparent in 13 of the 18 BV2 clones and might be involved in recognition of the HLA-DR/peptide complex. The key contacts should probably be the aromatic Y or W present in 14 clones, which could combine with the hydrophobic F in the centre of peptide 91–110. Additionally, a basic residue (R or K) present in eight clones also could combine with the acidic E at position 92 of peptide 91–110. Finally, the acidic E or D present in 15 of the 18 clones could combine with the basic R at position 100 of peptide 91–110. Because the latter amino acids are encoded by the BJ sequence and are normally conserved in their respective J segments, this suggests a role for this BJ-encoded germline sequence in the recognition of peptide 91–110/HLA-DR complexes.

Crystallographic data have illustrated recently how recognition of MHC-peptide complexes by monogamous TCR molecules [17,18] is dependent largely upon a single TCR pocket engaging a prominent side chain of the peptide antigen. It is thus possible to speculate that peptide antigens that can bind multiple MHC molecules (degenerate binders) can engage certain TCR chains that carry multiple binding pockets, generating an interaction of such strength as to overcome the usual apparent requirement for MHC restriction (promiscuous T cell recognition). Crystallographic and modelling data also indicate that different TCR–peptide–MHC complexes will have distinct structural orientations and contact points [16–22]. Finally, it has been shown that TCR is orientated in an orthogonal mode relative to its peptide-MHC ligand, necessitated by the amino-terminal extension of peptide residues projecting from the MHC class II antigen-binding groove as part of a mini beta sheet. Consequently, the disposition of the TCR CDR loops is altered relative to that of most peptide/MHC class I-specific TCRs; the latter TCRs assume a diagonal orientation, although with substantial variability [23,24].

Therefore, further analysis of the promiscuous BV2 TCRs in contact with the mycobacterial 16-kDa peptide 91–110 complexed with different HLA-DR molecules could reveal some unique features of this trimolecular interaction.

The identification of immunodominant and universal peptides applies to vaccine design, and has diagnostic relevance. The ability of peptide 91–110 to bind a wide range of HLA-DR molecules, and to stimulate a Th1-type IFN-γ response more readily, encourage the use of this peptide as a subunit vaccine component.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Prof. Vaclav Horejsi, Institute of Molecular Genetics, Academy of Science of the Czech Republic, Prague, for the provision of the MoAb MEM-115. We also thank Dr John D. McKinney (The Rockefeller University) for providing us with unpublished data and all colleagues at the Department of Immunology, Stockholm University, for technical help and advice. This work has been supported by grants from the Italian National Research Council (CNR) to FD and the Ministry for Education and Scientific and Technologic Research (MURST 60% to AS and FD).

REFERENCES

- 1.Flynn JL, Chan J. Immunology of tuberculosis. Annu Rev Immunol. 2001;19:93–129. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agrewala JN, Wilkinson RJ. Differential regulation of Th1 and Th2 cells by p91–110 and p21–40 peptides of the 16-kDa a-crystallin antigen of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Clin Exp Immunol. 1998;114:392–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1998.00724.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dieli F, Singh M, Spallek R, et al. Change of Th0 to Th1 cell-cytokine profile following tuberculosis chemotherapy. Scand J Immunol. 2000;52:96–102. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.2000.00744.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dieli F, Friscia G, Di Sano C, et al. Sequestration of T lymphocytes to body fluids in tuberculosis: reversal of anergy following chemotherapy. J Infect Dis. 1999;180:225–8. doi: 10.1086/314852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Friscia G, Vordermeier HM, Pasvol G, Harris DP, Moreno C, Ivanyi J. Human T cell responses to peptide epitopes of the 16-kDa antigen in tuberculosis. Clin Exp Immunol. 1995;102:53–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1995.tb06635.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saulquin X, Ibisch C, Peyrat MA, et al. A global appraisal of immunodominant CD8 T cell responses to Epstein–Barr virus and cytomegalovirus by bulk screening. Eur J Immunol. 2000;30:2531–9. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200009)30:9<2531::AID-IMMU2531>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chomczynski P, Sacchi N. Single step method of RNA isolation by a guanidinium thiocyanate phenol chlorophorm extraction. Ann Biochem. 1987;162:156–9. doi: 10.1006/abio.1987.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Friedl-Hajek R, Breitneder H, Bohle B, Fischer G, Ebner C, Scheiner O. Conserved sequence motif of CDR3 loops of TCR specific for two major epitopes of grass pollen allergen PHl p1. Int Immunol. 1998;10:1725–32. doi: 10.1093/intimm/10.11.1725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boitel B, Ermonval M, Panina-Bordignon P, Mariuzza RA, Lanzavecchia A, Acuto O. Preferential Vβ gene usage and lack of junctional sequenze conservation among human T cell receptors specific for a tetanus toxin-derived peptide: evidence for a dominant role of a germline-encoded V region in antigen/major histocompatibility complex recognition. J Exp Med. 1992;175:765–7. doi: 10.1084/jem.175.3.765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Toyonaga B, Yoshikai Y, Vadasz V, Chin B, Mak TW. Organization and sequences of diversity, joining, and constant region genes of the human T-cell receptor β-chain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:6824–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.24.8624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yassine-Diab B, Carmichael P, L’Faqihi FE, et al. Biased T-cell receptor usage is associated with allelic variation in the MHC class II peptide binding groove. Immumogenetics. 1999;49:532–40. doi: 10.1007/s002510050531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Agrewala JN, Wilkinson RJ. Influence of HLA-DR on the phenotype of CD4+ T lymphocytes specific for an epitope of the 16-kDa a-crystallin antigen of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Eur J Immunol. 1999;29:1753–61. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199906)29:06<1753::AID-IMMU1753>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Valle MT, Megiovanni AM, Merlo A, et al. Epitope focus, clonal composition and Th1 phenotype of the human CD4 response to the secretory mycobacterial antigen Ag85. Clin Exp Immunol. 2001;123:226–32. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2001.01450.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jurcevic S, Hills A, Pasvol G, Davidson RN, Ivanyi J, Wilkinson RJ. T cell response to a mixture of Mycobacterium tuberculosis peptides with complementary HLA-DR binding profile. Clin Exp Immunol. 1996;105:416–21. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1996.d01-791.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Friedl-Hajek R, Spangfort MD, Schou C, Breiteneder H, Yssel H, Joost van Neerven RJ. Identification of a higly promiscuous and HLA allele-specific T-cell epitope in birch major allergen Btt V1: HLA restriction, epitope mapping and TCR sequence comparisons. Clin Exp Allergy. 1999;29:478–87. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.1999.00489.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shi Y, Kaliyaperumal A, Lu L, et al. Promiscuous presentation and recognition of nucleosomal autoepitopes in lupus: role of autoimmune T cell receptor alpha chain. J Exp Med. 1998;187:367–78. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.3.367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garboczi DN, Ghosh P, Utz U, Fan QR, Biddison WE, Wiley DC. Structure of the complex between human T-cell receptor, viral peptide and HLA-A2. Nature. 1996;384:134–41. doi: 10.1038/384134a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garcia KC, Degano M, Stanfield RL, et al. An alpha-beta T cell receptor structure at 2·5 angstrom and its orientation in the TCR–MHC complex. Science. 1996;274:209–19. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5285.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jorgensen JL, Esser U, Reay PA, Fazekas de St Groth B, Davis MM. Mapping T cell receptor/peptide contacts by variant peptide immunization of single-chain transgenics. Nature. 1992;355:224–30. doi: 10.1038/355224a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nanda NK, Arzoo KK, Geysen HM, Sette A, Sercarz EE. Recognition of multiple peptide cores by a single T cell receptor. J Exp Med. 1995;182:531–9. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.2.531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sant’Angelo DB, Waterbury G, Preston-Hulbert P, et al. The specificity and orientation of a TCR to its peptide-MHC class II ligands. Immunity. 1996;4:367–76. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80250-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sun R, Shepherd SE, Geier SS, Thomson CT, Sheil JM, Nathenson SG. Evidence that the antigen receptors of cytotoxic T lymphocytes interact with a common recognition pattern on the H-2Kb molecule. Immunity. 1995;3:573–82. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90128-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ding YH, Smith KJ, Garboczi DN, Utz U, Biddison WE, Wiley DC. Two human T cell receptors bind in a similar diagonal mode to the HLA-A2/Tax peptide complex using different TCR amino acids. Immunity. 1998;8:403–11. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80546-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reinherz EL, Tan K, Tang L, et al. The crystal structure of a T cell receptor in complex with peptide and MHC class II. Science. 1999;286:1913–21. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5446.1913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]