Abstract

To target the neural cell adhesion molecule (NCAM, CD56) on neuroblastoma by T cell-based immunotherapy we have generated a bi-specific CD3 × NCAM antibody (OE-1). This antibody can be used to redirect T cells to NCAM+ cells. Expectedly, the antibody binds specifically to NCAM+ neuroblastoma cells and CD3+ T cells. OE-1 induces T cell activation, expansion and effector function in peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC)-derived CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. T cell activation was shown to depend on the presence of normal natural killer (NK) cells in the culture. Interestingly, while PBMC- derived T cells were activated by OE-1, NK cells were almost completely depleted, suggesting that T cells activated by OE-1 deleted the NK cells. Activated CD4+ and CD8+ T cells differentiate into a larger CCR7+ central memory and a smaller CCR7– effector memory cell population. Most importantly, preactivated T cells were highly cytotoxic for neuroblastoma cells. In eight of 11 experiments tumour-directed cytotoxicity was enhanced when NK cells were present during preactivation with OE-1. These data strongly support a bi-phasic therapeutic concept of primarily stimulating T cells with the bi-specific antibody in the presence of normal NCAM+ cells to induce T cell activation, migratory capacity and finally tumour cell lysis.

Keywords: bispecific antibodies, natural killer cells, neural cell adhesion molecule, neuroblastoma, T-cell activation

INTRODUCTION

Treatment of neuroblastoma is still a great challenge in paediatric oncology. More than one-third of all neuroblastoma patients die from their disease. The prognoses for children with high-risk neuroblastoma is even worse, with a survival rate of 30–40% [1]. New treatment approaches with anti-GD2 monoclonal antibodies achieved responses within selected patient groups [2,3], but are associated with side-effects limiting the clinical benefit [4]. Developing more sophisticated antibody-based concepts is expected to improve neuroblastoma treatment in future.

The neural cell adhesion molecule (NCAM, CD56) is expressed on nearly 100% of neuroblastomas [5], as well as on several normal tissues including the central nervous system (CNS), some neuroendocrine tissues and natural killer cells (CD56). The CNS is protected by the blood–brain barrier against systemically applied therapeutic antibodies. NCAM expression on neuroendocrine tissues appears to be weaker compared to neuroblastoma [6,7]. Targeting NCAM with specific antibodies or recombinant proteins result in protein phosphorylation and subsequent inhibition of cell proliferation, which has been shown particularly for neuroblastoma [8,9]. NCAM appears to be an especially promising target molecule for antibody-mediated immunotherapy.

Bi-specific monoclonal antibodies (bi-MoAbs) are capable of binding two different molecules: one antibody arm can bind a tumour-associated antigen (TAA), the other arm a leucocyte receptor. Bi-MoAbs are designed to recruit autologous leucocytes countering malignant tissues [10,11]. Employing T cells via CD3-epsilon × TAA antibodies is the most intensively studied bi-specific strategy. T cells are highly efficient cytotoxic effectors and play a central regulatory role in the immune network. Recently, the induction of a secondary and long-persisting antitumour memory was demonstrated in a mouse model after CD3 × TAA bi-MoAb treatment [12]. Clinical trials evaluating the locoregional application of CD3 × TAA bi-specific antibodies plus autologous human effector cells in patients with advanced stage glioblastoma and ovarian carcinoma demonstrated remarkable tumour regressions [13–15].

CD3 × TAA bi-specific antibodies first need to activate T cells by the CD3/TcR receptor complex before malignant tissues can be attacked [16,17]. T cell activation usually takes 2–4 days and requires preactivation by cross-linking T cells to tumour cells expressing the TAA for optimal results. Hence, bi-specific T cell activation in vivo is focused to the tumour site. Activated T cells up-regulate activation markers such as CD25 and CD69, begin to proliferate and become cytotoxic.

Malignant tissues are often infiltrated by so-called tumour infiltrating T lymphocytes (TIL). TIL are often anergic and poorly activated by CD3/TcR signalling, while peripheral T cells of the same patients are efficiently activated [18–20]. It would therefore be desirable to recruit the huge mass of available peripheral T cells to attack malignant tissues.

It was the aim of our study to combine the efficacy of CD3-mediated T cell recruitment with NCAM as a tumour marker. We hypothesize that a bi-specific CD3 × NCAM molecule would primarily link T cells with NK cells in the periphery before penetrating any malignant tissue. This raises several questions. Is it possible that T cells could not only be activated at the tumour site, but in the periphery? If this happens, would these T cells become cytotoxic for neuroblastoma cells? Alternatively, does the interaction between T cells and NK cells in the presence of the bi-specific CD3 × NCAM molecule reduce T cell function? Furthermore, we found it interesting to determine whether such T cells would differentiate further and thereby develop a cytotoxic phenotype expressing homing receptors for malignant tissues.

Here we show that the newly generated bi-specific MoAb OE-1 (CD3 × NCAM) activates peripheral blood derived T cells in the presence of NK cells to become effector memory T cells with homing properties for malignant tissues, capable of lysing neuroblastoma cells. While NK cells are diminished in number and function, T cell activation was enhanced by the T–NK cell interaction.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines and culture

The ERIC-1 hybridoma produces murine IgG1-κ antibodies specific for the neural cell adhesion molecule (NCAM, CD56) [5]. OKT3 hybridoma cells producing IgG2a-κ antibodies specific for the human CD3-epsilon chain were obtained from ATCC (CRL-8001). 15E8 hybridoma cells produce murine IgG1-κ antihuman CD28 antibodies [16]. Antibodies were purified from protein-free cell culture supernatants (SFM media, Life Technologies, Eggenheim, Germany) by protein G affinity chromatography and dialysed against phosphate buffered saline (PBS). Hybridoma cells, IMR-5 (human neuroblastoma), Jurkat (human T cell lymphoma), U266 (human plasma cell leukaemia), K562 (human erythroleukaemia) and Daudi (human B lymphoblast lymphoma) cells were grown in RPMI-1640 medium (Life Technologies, Eggenheim, Germany) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) (PAA, Linz, Austria), 2 mm Glutamax-ITM (Life Technologies) and 10 mg/l ciprofloxacin (Bayer, Leverkusen, Germany).

Isolation of the OE-1 hybrid–hybridoma

Using tetradoma technology [16] we generated a bi-specific antibody (OE-1, IgG2a/IgG1) specific for the T cell-receptor epsilon chain (CD3) and the neural cell adhesion molecule (NCAM, CD56). After selection in RPMI-1640 medium (Life Technologies) supplemented with 10% FCS and HAT (HAT = 2·5 × 10−3 m hypoxanthine, 1 × 10−5 m aminopterin, 4 × 10−4 m thymidine), supernatants from growing clones were tested for antibodies with IgG1/IgG2a heavy chain pairing by isotype-specific sandwich ELISA [16]. The well with the strongest ELISA signal was selected for repeated subcloning.

Purification and characterization of bispecific antibodies

An OE-1 master cellbank was established. To purify antibodies OE-1 hybrid–hybridoma cells were grown in SFM media (LifeTechnologies) and supernatants purified by single-step hydrophobic interaction chromatography [21]. All functional tests were carried out with bi-specific antibodies from the same batch to exclude batch to batch variations. Antibody binding was demonstrated by flow cytometry: Jurkat (CD3+, NCAM–), IMR-5 (CD3–, NCAM+), U266 (CD3–, NCAM–) and negative enriched (NK cell isolation kitTM, Miltenyi) peripheral blood NK (CD3–, NCAM+) cells were incubated with OE-1 antibodies (10 µg/ml, 15 min, 4°C) and both IgG1 and IgG2a heavy chains of the bi-specific antibody was detected by secondary isotype specific fluoroisothiocyanate (FITC)-coupled antibodies (10 µg/ml, 15 min, 4°C, Southern Biotechnology). ERIC-1 and OKT3 antibodies were used as controls. Cells were measured in a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, Heidelberg, Germany). To determine binding affinity OE-1 was [131I]-labelled using the chloramine-T method [22]. The binding affinity constant was calculated by means of Scatchard analysis [23]. No suitable coupling chemistry, leaving the CD3 site intact, could be found.

Immunohistochemistry

Thirteen fresh frozen neuroblastoma tissue sections and two normal lymph node sections (6 µm) were stained with haematoxylin and eosin (H&E). OE-1 was applied to tumour slices in various concentrations: 50 µg/ml, 10 µg/ml, 3·75 µg/ml and 2·5 µg/ml. A biotin–avidin method was used for staining as described earlier [24].

Measurement of T cell expansion in the presence of OE-1

PBMCs from healthy donors were incubated in round-bottomed plates at a density of 1 × 106/ml in AIM-V medium (Life Technology) + 10% human serum (PAA) + 10 mg/l ciprofloxacin. Antibody (OE-1, OKT3, ERIC-1, 15E8) concentrations were 1000 ng/ml. Viable cells at day 1 (baseline) and at day 6 were stained with CD4-FITC or CD8-FITC and CD16-PE (Becton Dickinson) and counted in a flow cytometer (FACSCalibur, Becton Dickinson). TruCountTM tubes were used to determine the absolute number of cells in each test. All tests were run in triplicate.

Magnetic activated cell sorting

Leukocyte subpopulations were separated using magnetic cell sorting technology (MACSTM, Miltenyi Biotech, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany). Depletion of CD56+ lymphocytes was performed using CD56-microbeads and negative enrichment of untouched natural killer cells was performed with the NK-cell isolation kitTM, both from PBMC, following the manufacturer's protocol.

BrdU assay

First PBMC were depleted from CD56+ cells by the MACSTM technique. Then NK cells from the same donor were negative enriched and re-added to the PBMC in a dilution series (PBMCCD56–: NK cells range: 100 : 0, 100 : 1·2, 100 : 3·7, 100 : 11·1, 100 : 33·3, 100 : 100) in order to obtain a defined NK cell concentration. 400 ng/ml antibodies: OE-1 + 15E8 or ERIC-1 + OKT3 + 15E8, were added. After incubation in flat-bottomed microtitre plates at a density of 0·5 × 106 cells/ml for 6 days BrdU was added 2 h prior to the evaluation of proliferating cells (BrdU cell proliferation ELISA, Roche molecular biochemicals). ELISA testing was carried out following the manufacturer's recommendations. After staining with substrate solution and stopping with H2SO4 absorption was measured at 450 nm wavelength in a microplate reader. All tests were run in triplicate.

Cytotoxicity assay

Target cells were labelled with europium (50 mm HEPES, 93 mm NaCl, 5 mm KCl, 2 mm MgCl2, 2 mm EuCl3, 10 mm diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid, pH 7·4) by single-pulse electroporation (500 V, 201 µF, 25 Ω, 5 ms). Cytotoxicity tests were carried out as described elsewhere [16,25].

To investigate T cell-mediated cytotoxicity against neuroblastoma cells after T cell activation from PBMC with OE-1 bi-MoAbs PBMCs were depleted from CD56+ cells and portioned over four cell culture flasks before negative enriched autologous NK cells were re-added to a final concentration of 30, 20, 10 or 0% NK cells in order to obtain defined NK cell contents; 400 ng/ml OE-1 + 400 ng/ml anti-CD28 antibodies then were added to initiate effector cell activation and NK cell elimination. After 4 days effector cells were harvested and tested against Europium-loaded IMR-5 cells. New OE-1 antibodies (1000 ng/ml) were added to reach receptor saturation. Control experiments were carried out by adding competitive ERIC-1 (5000 ng/ml) antibodies to verify antigen specificity of the cytolytic reaction.

T-cell phenotyping

The expression pattern of CD25, CD69, CCR7 and CD45RA were measured by flow cytometry. Therefore fresh isolated PBMC at a density of 0·5 × 106 cells/ml were incubated with 400 ng/ml OE-1 plus 1000 ng/ml 15E8 in RPMI-1640 medium + 10% FCS to initiate cell proliferation. Cells were stained at baseline and on days 3 and 6 with anti-CD4-PerCP, anti-CD8-PerCP, anti-CD25-FITC, anti-CD69-FITC or anti-CCR7-PE and anti-CD45RA-FITC antibodies (all antibodies from Becton Dickinson, anti-CCR7 antibody from R&D Systems, Wiesbaden, Germany), and measured in a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson).

Statistical analyses

The Student's t-test for two paired samples was used to determine statistically significant differences. The Wilcox test for two-paired samples was used to determine statistically significant differences in the results of the BrdU tests. For regression of the dose–response curve we applied the Michaelis–Menten kinetic law. The kinetic is defined as V = b + Vmax* ([20]/([S] + Km)), where b is an added constant to define the baseline. The curves were computed using the iterative methods for non-linear regression of SPSS. All calculations were performed using SPSS version 10·0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

RESULTS

The bi-specific antibody OE-1 binds specifically CD3 and NCAM

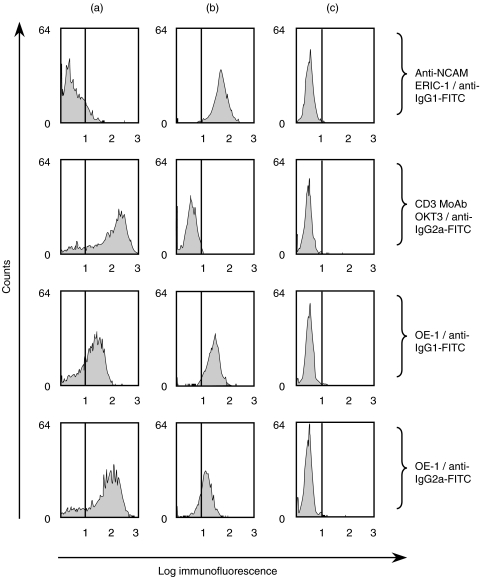

To test specific binding of the bi-specific antibody OE-1 (IgG2a/IgG1) to CD3 and NCAM, we performed FACS analyses using CD3+ NCAM– Jurkat cells, CD3– NCAM+ IMR-5 cells and CD3– NCAM– U266 cells. Similar to the NCAM specific ERIC-1 MoAb, the bi-specific OE-1 stained NCAM+ IMR-5 cells but not NCAM– U266 cells. OE-1 also stained CD3+ Jurkat cells as shown for the CD3 MoAb, but not CD3– U266 cells. These experiments demonstrate clearly the bispecific nature of OE-1 (Fig. 1). Flow cytometry analyses with negative enriched peripheral blood NK cells also demonstrated binding of OE-1. Competition experiments with radioactive labelled OE-1 demonstrated a similar KD value < 10−9 of the parental ERIC-1 antibody, as well as the NCAM binding site of OE-1. Measuring the affinity of the CD3 binding site was not possible, as no suitable coupling chemistry leaving the CD3 site intact could be found. Nevertheless, all phenotypical and functional tests concerning CD3 showed very similar results for OKT3 and OE-1.

Fig. 1.

Demonstration of OE-1 binding to CD3 or NCAM expressing cells using flow cytometry. (a): Jurkat cells (CD3+, NCAM–) incubated with OE-1 MoAb and secondary goat antimouse-IgG1-FITC or goat antimouse-IgG2a-FITC, respectively. Parental CD3 MoAb and anti-NCAM MoAb were used as a control. (b): IMR-5 (CD3–, NCAM+). (c): U266 (CD3–, NCAM–).

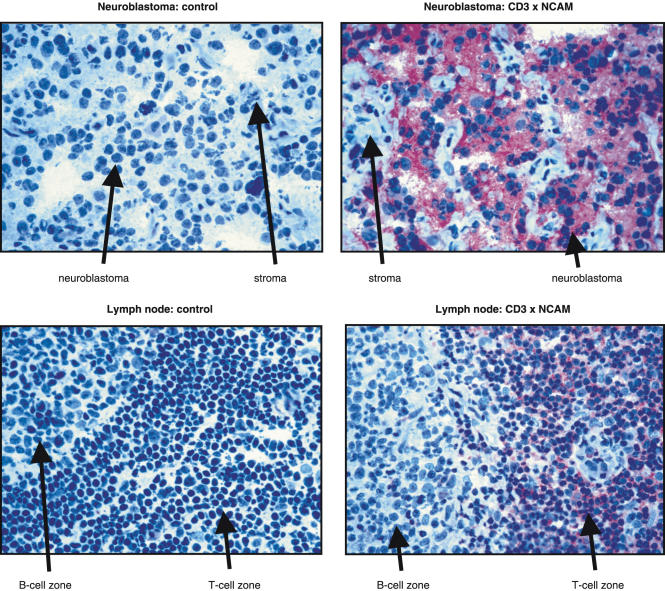

Immunohistochemistry

Similar to ERIC-1, OE-1 bound specifically to NCAM+ neuroblastoma sections but not to infiltrating stroma cells. A strong staining was found in 13 of 13 samples tested independently of histological grading (five G3 cases, four G2 cases, three G1a cases and one G1b case) according to Hughes et al.'s classification [26], suggesting that OE-1 can efficiently recognize NCAM on neuroblastoma cells. Lymphocyte staining in the T cell zone in two of two lymph nodes was positive while stroma cells and lymphocytes of the B cell zone were negative. These experiments demonstrate the ability of OE-1 to detect T cells and neuroblastoma cells in situ(Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Immunohistochemical staining showing OE-1 binding to neuroblastoma and lymph node sections. Left side: the negative control showed no staining in neuroblasts and lymph node tissue. Right side: the upper picture demonstrated a strong staining for OE-1 in the neuroblasts while the stroma cells were negative. In the lower picture the T cells reacted positive for OE-1 while the B-cell zone was negative. Magnification × 400.

OE-1 stimulates T cell expansion in PBMC ex vivo cultures

To test whether OE-1 would stimulate CD3+ or NCAM+ immune cells in peripheral blood, we performed experiments measuring T cell and NK cell functions. First we investigated whether OE-1, similar to OKT3 MoAb, can stimulate T cells to proliferate. PBMC from seven healthy donors were stimulated by either OE-1 or CD3 plus anti-NCAM MoAb in the presence of co-stimulatory CD28 MoAb (15E8). Expansion of CD4+ and CD8+ T cell subsets were analysed by cell counting after a 6-day culture. Similar to CD3 MoAb, OE-1 induced significant expansion of CD4+ T cells [twofold increase for OE-1 (range 1·11–3·95); 1·79-fold increase for the CD3 MoAb (range 1·21–4·00)]. In only two of seven tests did OE-1 induce a significantly stronger CD4+ T cell proliferation compared with CD3 MoAbs (Fig. 3a). In the absence of any CD3/TcR complex-mediated stimulation, CD4+ T cell numbers were reduced. The number of CD8+ T cells increased by 2·19-fold (range 1·30–4·91) when cultured in the presence of OE-1, but only 1·55-fold (range 1·01–4·41) in the presence of CD3 MoAb. OE-1 induced a significantly stronger T cell proliferation than CD3 MoAbs in six of seven tests demonstrating a favourable CD8+ T cell proliferation. Again CD8+ T cell counts decreased in the absence of stimulation. Interestingly, we observed a prominent interindividual variation of cell expansion for both CD3 MoAb and the bi-specific OE-1 MoAb; however, expansion was higher when stimulating with OE-1 in six of seven donors (Fig. 3b).

Fig. 3.

Expansion of PBMC-derived T cells cocultured with the bi-specific MoAb OE-1. (a) CD4+ T cells: PBMC were incubated with OE-1 plus CD28 costimulatory MoAb (black bar), CD3 MoAb plus anti-NCAM MoAb plus CD28 MoAb (grey bar) or medium alone (white bar). CD4+ T cell density measured at start and at day 6 in a flow cytometer. Proliferative index was calculated. The results from seven different donors are shown. Overall expansion rate was calculated as follows: CD4+ T cell counts at day 6/CD4+ T cells counts at day 0. In two of seven experiments OE-1-induced T cell proliferation was significantly stronger (P < 0·05) than in the controls (no. II and no. VII). In the other experiments the difference was not significant. (b) Expansion of CD8+ lymphocytes in these cultures. In six of seven experiments OE-1-induced T cell proliferation was significantly (P < 0·05) stronger than in the controls. Only in experiment no. 4 was the difference not significant. (c) Cell proliferation as measured in a BrdU incorporation ELISA. PBMC were depleted from NCAM+ cells and plated on a MTP. Purified autologous natural killer cells then were re-added in a dilution series (range: 100 : 0, 100 : 1·2, 100 : 3·7, 100 : 11·1, 100 : 33·3, 100 : 100). Antibodies were as follows: OE-1 plus CD28 MoAb (filled circles) or CD3 plus anti-NCAM plus CD28 MoAb (open boxes). One representative experiment of six is shown.

To determine whether NCAM+ NK cells might influence expansion of CD8+ T cells in these cultures a series of experiments were performed:

Similar to the experiments described above, PBMCs from a healthy donor were stimulated by either OE-1 or CD3 MoAb in the presence of costimulatory CD28 MoAb (15E8). Expansion of cell subsets was analysed by cell counting after a 6-day culture. No cell proliferation was seen for leucocyte subpopulations (CD14+, CD16+ and CD19+) other than T cells.

Next we used PBMC depleted of CD56+ cells and re-added NK cells in a dilution series (PBMCCD56–:NK cells range: 100 : 0, 100 : 1·2, 100 : 3·7, 100 : 11·1, 100 : 33·3, 100 : 100). The addition of increasing numbers of CD56+ cells led to an increased proliferative response of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the presence of OE-1 bi-specific MoAb, but not in the presence of parental CD3 and anti-NCAM MoAb or absence of antibodies.

To allow further analyses over a broader range of donors, we changed the analysis technique to a BrdU incorporation ELISA. Again we used PBMC depleted from CD56+ cells and re-added NK cells in a dilution series (PBMCCD56–: NK cells range: 100 : 0, 100 : 1·2, 100 : 3·7, 100 : 11·1, 100 : 33·3, 100 : 100). A total of nine experiments were carried out, where six tests confirmed the observation and three tests failed. In the model used, we propose that in the presence of OE-1 the NK-cells induce an increase of cell-proliferation according to the Michaelis–Menten kinetic. A representative set of data are shown in Fig. 3c. The present data from six experiments (Table 1) demonstrate a significant increase of cell-proliferation dependent on the NK-cell concentration using the Wilcox test for two-paired samples (P = 0·028).

Table 1.

Results from six different experiments measuring OE-1-induced cell proliferation as shown in Fig. 3c. Experiment 1 represents the same set of data as Fig. 3c; experiments 2–5 represent additional experiments

| Experiment | OKT3: calculated proliferation index | OE-1: calculated proliferation index | Wilcox’s rank test |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2·9 | 15·8 | p = 0·028 |

| 2 | 1·2 | 5·7 | p = 0·028 |

| 3 | 9·2 | 13·6 | p = 0·028 |

| 4 | 1·3 | 3·2 | p = 0·028 |

| 5 | 1·2 | 2·3 | p = 0·028 |

| 6 | 3·2 | 4·1 | p = 0·028 |

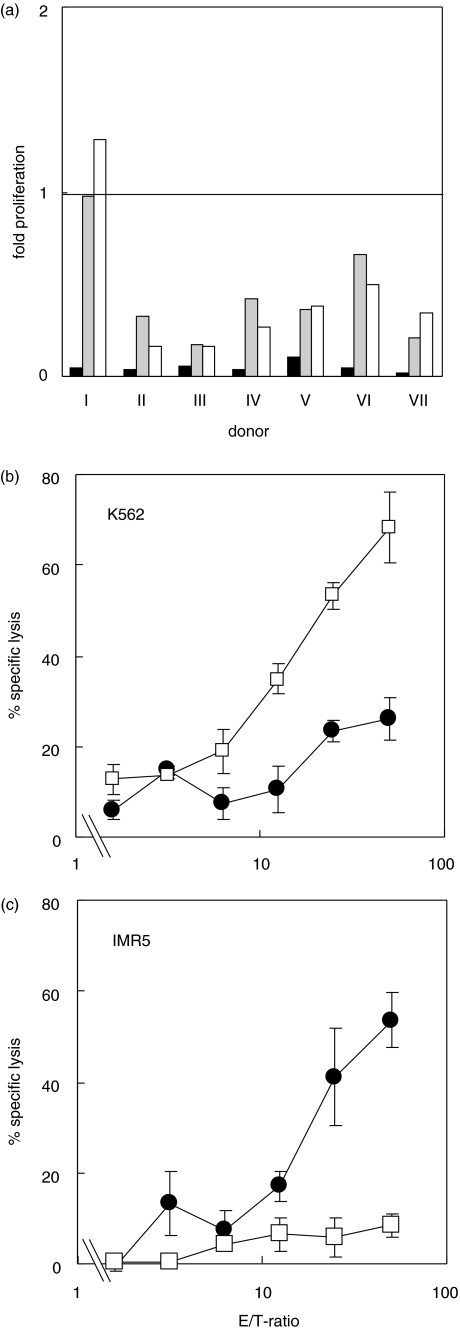

Loss of NK cells after incubation of PBMC with OE-1

We were next interested in determining whether NCAM+ NK cells would also expand after activation by OE-1 through NCAM binding. However, after analysing absolute CD16+ cell counts after incubation of PBMC with OE-1, NK cells were almost completely depleted (mean of 6% of initial cell number in seven experiments, Fig. 4a), while NK cell count was significantly higher in cultures without antibodies (mean of 44% of initial cell number) or with parental CD3 and anti-NCAM MoAb (mean of 43% of initial cell number). The complete loss of NK cell function from PBMC after incubation with OE-1 defined as lysis of K562 cell was also documented (Fig. 4b). A cytotoxicity assay with PBMC from the same OE-1 activated sample was carried out simultaneously as a control to give evidence for successful stimulation and functional activity against IMR-5 cells (Fig. 4c).

Fig. 4.

(a) Counting of natural killer cells from the same PBMC probes as in Fig. 3 (a + b). CD16+ cells were counted at day 0 and day 6. Black bar: OE-1 + CD28 MoAb; grey bar: CD3 plus anti-NCAM plus CD28 MoAb; white bar: medium control. In seven of seven experiments the OE-1-induced NK cell depletion was significant stronger (P < 0·05) than in the controls. (b) Cytotoxicity against K562 NK sensitive target cells (CD56–). PBMC were activated with either CD3 plus CD28 MoAb (open boxes) or OE-1 + CD28 MoAb (filled circles). OE-1-activated PBMC revealed a significantly weaker (P < 0·05) cytotoxicity against K562 cells seen at E/T ratios ranging from 6·25 : 1 to 50 : 1. (c) Measurement of cytotoxic T cell activity against IMR-5 neuroblastoma cells (NCAM+) from the same PBMC samples as in Fig. 4b after addition of new OE-1 antibodies. OE-1 activated PBMC demonstrated a significantly stronger cytotoxicity (P < 0·05) against IMR-5 seen at E/T-ratios ranging from 12·5 : 1 to 50 : 1. The test was repeated once with K562 and twice with Daudi cells revealing similar results.

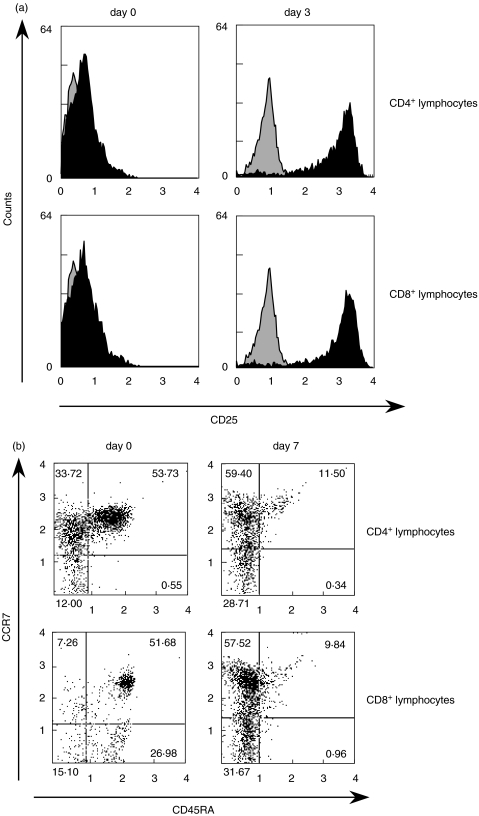

Characterization of CD4+ and CD8+ T cell subsets after activation by OE-1

T cells, originally negative for CD25 and CD69 amplified both activation markers significantly within 3 days. In particular, CD25 were strongly multiplied on approximately 100% of all CD4 and CD8+ T cells (Fig. 5a).

Fig. 5.

Surface marker measurement on OE-1-activated PBMC. T cell subpopulations were identified by CD4+- and CD8+-PerCP coupled antibodies. (a) Measurement of CD25 activation marker at day 0 and day 3 after activating PBMC with OE-1 bi-MoAb + CD28 MoAb. (b) Measurement of CD45RA and the CCR7 chemokine receptor at day 0 and day 7 after activating PBMC with OE-1 bi-MoAb + CD28 MoAb. Relative numbers of cells are indicated in each quadrant. Experiment B was carried out three times, revealing similar results.

After stimulation with OE-1, a loss of CD45RA in a vast majority of T cells was observed while CD45RA negative cells could be divided into a larger CCR7+ group and a smaller CCR7– group. The experiment was carried out three times with similar results. Flow cytometry analyses every 24 h demonstrated that loss of CD45RA was a slow but continuous process during the observation time (7 days). At day 7 the CCR7–/CD45RA– population was about 31% for CD8+ T cells and 28% for CD4+ T cells (Fig. 5b). The CCR7+/CD45RA– population was 57%, respectively, 59% for CD8+ and CD4+ T cells.

Enhancement of cytotoxicity

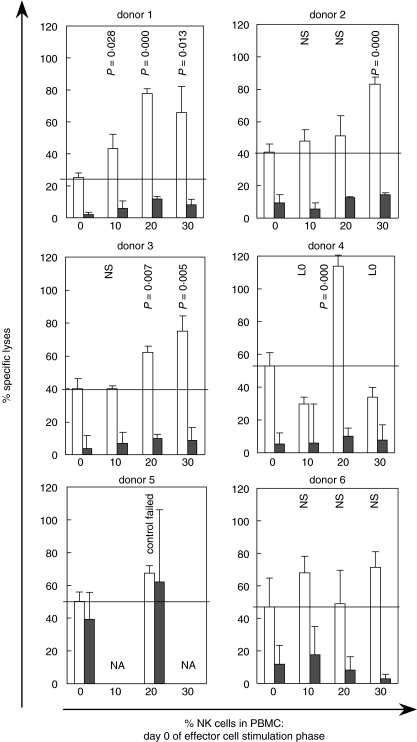

It was important to verify whether OE-1 activated T cells are capable to mediate cytolysis against a malignant target after the prior struggle with NK cells. PBMC were depleted from CD56+ cells and portioned over four cell culture flasks before isolated autologous NK cells were re-added to a final concentration of 30, 20, 10 or 0% NK cells; 400 ng/ml OE-1 + 400 ng/ml anti-CD28 antibodies were substituted to initiate effector cell activation and NK cell elimination. After 4 days effector cells were harvested and assayed using Europium-loaded IMR-5 cells. New OE-1 antibodies (1000 ng/ml) were added to the tests to reach receptor saturation. Control experiments were carried out by adding competitive ERIC-1 (5000 ng/ml) antibodies to demonstrate that T cells were the source of the cytolytic reaction observed, not the NK cells.

Altogether the experimental outcome was variable (seen the 6 experiments shown in Fig. 6). However, eight out of 11 experiments provided evidence for an enhanced T cellular cytotoxicity after OE-1 induced T-/NK–cell interaction. Increased cytotoxicity was seen mainly when 20% or more NK cells were present during the activation phase. The difference in cytotoxic activity corresponds to more than 50% of the specific lysis. Cytotoxicity against IMR-5 was poor or not detectable, when T cells were not prestimulated.

Fig. 6.

T cellular cytotoxicity redirected against IMR-5 (NCAM+) neuroblastoma cells. PBMC-derived T cells were activated using bi-specific OE-1 MoAb plus CD28 MoAb. For each test PBMCs were depleted of CD56+ cells and defined numbers of autologous CD56+ NK cells were re-added prior to activation. After 4 days activated T cells were assayed against IMR-5 (NCAM+) neuroblastoma cells in a Europium release assay. Fresh OE-1 MoAb (1000 ng/ml) was added to the assay to achieve receptor saturation and competitive parental anti-NCAM MoAb (5000 ng/ml) to determine remaining NK cell-mediated lysis. E/T ratio was 50 : 1. The horizontal line marks the level of cytotoxicity when no NK cells were present during the preactivation phase. Six representative experiments of 11 are shown. White bar = OE-1 bi-MoAb; black bar = OE-1 bi-MoAb + ERIC-1 MoAb; n.a. = not available; n.s. = no significant difference compared with 0% NK cells; L0 = cytotoxicity lower compared with 0% NK cells; P-values were indicated when a level of significance <0·05 was reached compared with 0% NK cells.

DISCUSSION

We have demonstrated here that OE-1 antibodies induce T cell activity in peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Notably, T cell proliferation and tumour-directed cytotoxicity as induced by OE-1 was enhanced by autologous natural killer cells.

After T cell stimulation by OE-1, cells differentiate into a CCR7+/CD45RA– and a CCR7–/CD45RA– population. According to Sallusto et al. [27], CCR7–/CD45RA– T cells are ‘effector memory cells’ (TEM cells) displaying immediate effector functions and expressing receptors for migration into malignant tissues. Although no in vivo data on OE-1 are available, it might be speculated that T cells activated by OE-1 in the periphery transform into cytotoxic TEM cells and migrate thereafter into neuroblastoma tissue and attack the tumour. If this is correct, in vivo recruitment of the huge mass of peripheral T cells may circumvent local T cell suppression by malignant tissues.

Central memory T cells are characterized as CCR7+/CD45RA– T cells are ‘central memory cells’ (TCM cells) [27]; they displaying homing properties for lymphoid tissues and exercise regulatory functions in the immune network. Occurrence of TCM cells after bi-specific CD3 × NCAM T cell stimulation might represent an immunomodulatory effect of OE-1. Further, it is known that TCM cells can differentiate into TEM cells upon secondary stimulation displaying homing properties for tumour tissue and cytotoxic function [27].

A complete NK cell depletion by OE-1 as observed was due most probably to direct T cell activity against NK cells. Under physiological conditions NK and T cells collaborate in inflamed tissues and should not eliminate each other. In contrast to our observations Malygin et al. [28] found NK cell proliferation and T cell depletion after adding CD3 × CD16 bi-specific F(ab′)2 antibodies plus IL-2 to isolated PBMC. This might be explained partially by the different cellular receptors used. In preliminary experiments we did not find signs of NK cell activation as shown by intracellular cytokine staining and reverse ADCC test. However, a transient NK cell depletion, as observed in our experiments, might be tolerated in an in vivo situation, as this also occurs after standard chemotherapy. NK cell precursors are CD56 negative and should not be affected by OE-1 [29].

We developed a two-phase hypothetical model on the in vivo action of the OE-1 bi-MoAb: phase I includes a broad and systemic T cell activation, resulting in the development of cytotoxic T memory effector cells displaying homing properties for malignant tissues. In phase II, activated T cells migrate into the tumour tissue and execute highly efficient cytotoxicity. This new strategy is currently under investigation in a murine model.

For the therapeutic development of OE-1 it will be necessary to reduce immunogenicity, e.g. by humanizing the antibody and deleting the Fc portion of the bi-specific antibody. Furthermore, certain formats of recombinant bi-MoAbs have been described in recent years, of which the so-called bi-specific diabody approach is particularly promising. Diabodies were constructed from the variable parts of immunoglobulin light (L)- and heavy (H) chains: two fusion proteins, H1–L2 and H2–L1, were co-expressed in a bacterial expression system. After protein syntheses chains can associate to intact bi-specific molecules. If required, diabodies can be humanized partly or completely. Bi-specific diabodies lack the Fc part and do not induce cytokine release due to T cell cross-linking with Fcγ-receptor-expressing bystander cells. Cytokine release induced side-effects are suspected to be less compared with ‘complete’ bi-specific antibodies.

These steps towards a therapeutic antibody are currently under way in our laboratory.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Rolf Zinkernagel for discussing the data. We especially thank Mrs Marion Battenberg for expert technical assistance. We also thank Dr Klaus Schomäker and Dr Thomas Fischer for radioactive labelling experiments. This work was supported by the Köln Fortune Program/Faculty of Medicine, University of Cologne, Germany. JLS is supported by the Sofja-Kovalevskaja Award of the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation. FB is supported by the German Cancer Aid (Deutsche Krebshilfe).

REFERENCES

- 1.Berthold F, Hero B. Neuroblastoma: current drug therapy recommendations as part of the total treatment approach. Drugs. 2000;59:1261–77. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200059060-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kushner B, Kramer K, Cheung N. Phase II trial of the anti-G (D2) monoclonal antibody 3F8 and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor for neuroblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:4189–94. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.22.4189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheung N, Kushner B, Cheung I, et al. Anti-G (D2) antibody treatment of minimal residual stage 4 neuroblastoma diagnosed at more than 1 year of age. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:3053–60. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.9.3053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kremens B, Hero B, Esser J, et al. Ocular symptoms in children treated with human-mouse chimeric anti-GD2 MoAb ch14.18 for neuroblastoma. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2002;51:107–10. doi: 10.1007/s00262-001-0259-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bourne S, Patel K, Walsh F, Popham C, Coakham H, Kemshead J. A monoclonal antibody (ERIC-1), raised against retinoblastoma, that recognizes the neural cell adhesion molecule (NCAM) expressed on brain and tumours arising from the neuroectoderm. J Neurooncol. 1991;10:111–9. doi: 10.1007/BF00146871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roy D, Ouellet S, Le HC, Ariniello P, Perreault C, Lambert J. Elimination of neuroblastoma and small-cell lung cancer cells with an anti-neural cell adhesion molecule immunotoxin. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1996;88:1136–45. doi: 10.1093/jnci/88.16.1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hirano T, Hirohashi S, Kunii T, Noguchi M, Shimosato Y, Hayata Y. Quantitative distribution of cluster 1 small cell lung cancer antigen in cancerous and non-cancerous tissues, cultured cells and sera. Jpn J Cancer Res. 1989;80:348–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.1989.tb02318.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krushel L, Tai M, Cunningham B, Edelman G, Crossin K. Neural cell adhesion molecule (N-CAM) domains and intracellular signaling pathways involved in the inhibition of astrocyte proliferation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:2592–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.5.2592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dehal P, Embleton M, Kemshead J, Hawkins R. Targeted cytokine delivery to neuroblastoma. Biochem Soc Trans. 2002;30:518–20. doi: 10.1042/bst0300518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Staerz U, Kanagawa O, Bevan M. Hybrid antibodies can target sites for attack by T cells. Nature. 1985;314:628–31. doi: 10.1038/314628a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Featherstone C. Bispecific antibodies: the new magic bullets. Lancet. 1996;348:536. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(05)64681-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ruf P, Lindhofer H. Induction of a long-lasting antitumor immunity by a trifunctional bispecific antibody. Blood. 2001;98:2526–34. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.8.2526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nitta T, Sato K, Yagita H, Okumura K, Ishii S. Preliminary trial of specific targeting therapy against malignant glioma. Lancet. 1990;335:368–71. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)90205-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jung G, Brandl M, Eisner W, et al. Local immunotherapy of glioma patients with a combination of 2 bispecific antibody fragments and resting autologous lymphocytes: evidence for in situ T-cell activation and therapeutic efficacy. Int J Cancer. 2001;91:225–30. doi: 10.1002/1097-0215(200002)9999:9999<::aid-ijc1038>3.3.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Canevari S, Stoter G, Arienti F, et al. Regression of advanced ovarian carcinoma by intraperitoneal treatment with autologous T lymphocytes retargeted by a bispecific monoclonal antibody. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1995;87:1463–9. doi: 10.1093/jnci/87.19.1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hombach A, Tillmann T, Jensen M, et al. Specific activation of resting T cells against tumour cells by bispecific antibodies and CD28-mediated costimulation is accompanied by Th1 differentiation and recruitment of MHC-independent cytotoxicity. Clin Exp Immunol. 1997;108:352–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1997.3481245.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weiner G, Kostelny S, Hillstrom J, Cole M, Link B, Wang S, Tso J. The role of T cell activation in anti-CD3 × antitumor bispecific antibody therapy. J Immunol. 1994;152:2385–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miescher S, Whiteside T, von Carrel SFV. Functional properties of tumor-infiltrating and blood lymphocytes in patients with solid tumors: effects of tumor cells and their supernatants on proliferative responses of lymphocytes. J Immunol. 1986;136:1899–907. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cardoso A, Schultze J, Boussiotis V, et al. Pre-B acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells may induce T-cell anergy to alloantigen. Blood. 1996;88:41–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Agrawal S, Marquet J, Delfau-Larue M, et al. CD3 hyporesponsiveness and in vitro apoptosis are features of T cells from both malignant and nonmalignant secondary lymphoid organs. J Clin Invest. 1998;102:1715–23. doi: 10.1172/JCI3784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Manzke O, Tesch H, Diehl V, Bohlen H. Single-step purification of bispecific monoclonal antibodies for immunotherapeutic use by hydrophobic interaction chromatography. J Immunol Meth. 1997;208:65–73. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(97)00129-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Greenwood F, Hunter W, Glover J. The preparation of 131J-labelled humen growth hormone of high specific radioactivity. Biochem J. 1963;89:114–23. doi: 10.1042/bj0890114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scatchard G. The attraction of proteins for small molecules and ions. NY Acad Sci. 1949;51:660–72. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hell K, Lorenzen J, Hansmann M, Fellbaum C, Busch R, Fischer R. Expression of the proliferating cell nuclear antigen in the different types of Hodgkin's disease. Am J Clin Pathol. 1993;99:598–603. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/99.5.598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bohlen H, Manzke O, Engert A, Hertel M, Hippler-Altenburg R, Diehl V, Tesch H. Differentiation of cytotoxicity using target cells labelled with europium and samarium by electroporation. J Immunol Meth. 1994;173:55–62. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(94)90283-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hughes M, Marsden H, Palmer M. Histologic patterns of neuroblastoma related to prognosis and clinical staging. Cancer. 1974;34:1706–11. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197411)34:5<1706::aid-cncr2820340519>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sallusto F, Lenig D, Forster R, Lipp M, Lanzavecchia A. Two subsets of memory T lymphocytes with distinct homing potentials and effector functions. Nature. 1999;401:708–12. doi: 10.1038/44385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Malygin A, Somersalo K, Timonen T. Promotion of natural killer cell growth in vitro by bispecific (anti-CD3 × anti-CD16) antibodies. Immunology. 1994;81:92–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sivori S, Falco M, Marcenaro E, et al. Early expression of triggering receptors and regulatory role of 2B4 in human natural killer cell precursors undergoing in vitro differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:4526–31. doi: 10.1073/pnas.072065999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]