Abstract

Protection against intracellular pathogens such as Mycobacterium leprae is critically dependent on the function of NK cells at early stages of the immune response and on Th1 cells at later stages. In the present report we evaluated the role of IL-18 and IL-13, two cytokines that can influence NK cell activity, in the generation of M. leprae-derived hsp65-cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL) from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) of leprosy patients. We demonstrated that IL-18 modulates hsp65-induced CTL generation and collaborates with IL-12 for this effect. In paucibacillary (PB) patients and normal controls (N) depletion of NK cells reduces the cytolytic activity. Under these conditions, IL-12 cannot up-regulate this CTL generation, while, in contrast, IL-18 increases the cytotoxic activity both in the presence or absence of NK cells. IL-13 down-regulates the hsp65-induced CTL generation and counteracts the positive effect of IL-18. The negative effect of IL-13 is observed in the early stages of the response, suggesting that this cytokine affects IFNγ production by NK cells. mRNA coding for IFNγ is induced by IL-18 and reduced in the presence of IL-13, when PBMC from N or PB patients are stimulated with hsp65. Neutralization of IL-13 in PBMC from multibacillary (MB) leprosy patients induces the production of IFNγ protein by lymphocytes. A modulatory role on the generation of hsp65 induced CTL is demonstrated for IL-18 and IL-13 and this effect takes place through the production of IFNγ.

Keywords: leprosy, NK cells, cytotoxicity, IL-18, IL-13

INTRODUCTION

The production of proinflammatory cytokines by phagocytic cells during infections starts a cascade of cellular reactions resulting in inflammation and activation of effector cells of innate immunity. Depending on the cytokine milieu, these early events will lead the immune response towards type 1 or type 2 activities which can reciprocally regulate each other. Upon infection with bacteria or intracellular parasites, monocytes/macrophages produce interleukin (IL)-12 which is modulated by positive and negative feedback signals [1–4]. IL-12 is required for proliferation and for IFNγ production by natural killer (NK) cells and differentiated T cells. It has been reported that IL-1, IL-2, IL-12, IL-18 and TNFα are potent inductors or coinductors of IFNγ in NK and T cells [3–9]. In addition, IFNγ regulates a variety of immunological responses in both innate and acquired immunity. In mycobacterial infections release of IL-2 and IFNγ is generally associated with resistance to intracellular infections, whereas release of IL-4 and IL-10 is associated with progressive disease [10,11]. As IL-12, IL-18 is a macrophage/monocyte derived cytokine that participates in the induction of IFNγ production, in the increase of NK activity and in the stimulation of Th1 cell differentiation [12–14]

NK cells were initially defined for their ability to spontaneously lyse certain tumour cells and virally infected cells. However they do not lyse normal cells from the same host. NK cells recognize their target cells by different receptors that determine their function [15]. Beyond their capacity to kill specific target cells, NK cells are also capable of producing type 1 or type 2 cytokines. The early migration of IFNγ-producing NK cells into the inflammatory sites is important in the generation of a Th1 response. On the other hand, enhancement of NK cytotoxicity by IL-18 does not require endogenous IL-12 production probably because the IL-18 receptor (IL-18R) is constitutively expressed on the surface of NK cells [14]. Recent studies have revealed that IL-18 does not require help from IL-12 to induce Th2 cytokines production in T and NK cells while it induces IL-13 production by the same cells acting synergistically with IL-2 when IFNγ is lacking [16]. IL-13 is a pleiotropic cytokine derived from activated T cells that acts on monocytes, macrophages, NK cells and normal and malignant B cells and is also involved in the development of humoral immunity [17]. Although IL-13 has only 30% sequence homologuey with IL-4, both share biological functions by inducing the activation of STAT6 and JAK3 but differentially regulate functional activities in fresh primary T and NK cells [18,19]. IL-13 strongly inhibits the production of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines by LPS-activated monocytes [19].

Leprosy is an infectious disease caused by Mycobacterium leprae in which the clinical manifestations correlate with the cell-mediated immunity (CMI). At one pole, tuberculoid leprosy is characterized by strong CMI and a Th1 cytokine pattern has been documented in the lesions [10,11], on the other pole, lepromatous leprosy patients are weak responders to M. leprae antigens and their lesions are characterized by a Th2 cytokine pattern. Arrest of mycobacterial growth is thought to be mediated in part by cytotoxic T lymphocytes and, as we have previously demonstrated, multibacillary (MB) patients are unable to generate a cytotoxic response to M. leprae heat shock protein 65 (hsp65) [20]. Considering that protection against intracellular pathogens is critically dependent on the function of NK cells at early stages of the immune response and on Th1 cells at later stages, we evaluated the role of IL-18 and IL-13, two cytokines that are able to influence NK cell activity, in the hsp65-CTL generation in PBMC from leprosy patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

Twenty-one leprosy patients, diagnosed on the basis of clinical and bacteriological criteria and classified according to Ridley and Jopling [21], were studied: 11 lepromatous (LL), 3 borderline lepromatous (BL), 4 tuberculoid (TT) and 3 borderline tuberculoid patients (BT). They were divided into two groups: paucibacillary (PB: TT and BT) (3F, 4M; age range 33–72 years) and multibacillary (MB: LL and BL) (8F, 6M; age range 19–76 years) patients. Their informed consent for experimentation was obtained according to the Ethics Commission of the Hospital Francisco J. Muñiz. MB patients undergoing an ENL episode and those taking thalidomide or corticoids were excluded. All the patients included in this study were free of other infectious diseases and those under treatment received multidrug therapy (MDT) according to the recommendations of the World Health Organization. Most of the patients came from or were residing in endemic areas at the moment of the study. Eight BCG-vaccinated normal controls (N) (5 women, 3 men; 24–60 years) were studied simultaneously.

Mononuclear cells

Heparinized blood was collected and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were isolated by Ficoll-Hypaque gradient centrifugation [22]. Cells were collected from the interface and resuspended in RPMI 1640 tissue culture medium (Gibco Laboratory, NY, USA) containing gentamycin (85 µg/ml) and 15% heat inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS) (Gibco Laboratory) (complete medium).

Effector cells for cytotoxicity assays

PBMC (2 × 106 cells/ml) were cultured in Falcon 2063 tubes (Becton Dickinson, Lincoln, PK, NJ, USA) at 37°C in humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere, in complete medium with or without the 65 kD (10 µg/ml) recombinant protein from M. leprae (hsp 65), in the presence or absence of: IL-12 (10 ng/ml), IL-18 (10 ng/ml), IL-13 (10 ng/ml) and monoclonal antibodies (MAb) against IL-18 (mouse, class type IgG1/kappa, 10 ng/ml), IL-12 (mouse, IgG1) or IL-13 (rabbit, polyclonal antigen affinity purified, bioactivity: 1 ng/ml neutralizes 1 µg/ml IL-13) (10 ng/ml), or combinations of the cytokines with the different antibodies mentioned above. Hsp 65 (batch ML10-2) was kindly provided by Dr M. Singh, GBF, Braunschweig, Germany, through the UNDP/World Bank/WHO); the endotoxin concentration was 1·65 × 103 units/mg of protein according to Limulus amoebocyte lysate assay. IL-18 and IL-13 were purchased from Peprotech Inc (Rocky Hill, NJ, USA) and IL-12 from R & D Systems, (Minneapolis, MN, USA), all of them were recombinant proteins. Monoclonal anti-human IL-18 and polyclonal anti-human IL-13 antibodies were purchased from Peprotech (USA). On day 7, treated and control cells were washed three times with RPMI 1640, resuspended in complete medium (1 × 106 cells/ml) and tested for cytotoxic activity.

Isolation of NK-depleted PBMC

PBMC were depleted of lymphocytes bearing the CD56 and CD16 antigens by a magnetic method. Briefly, a total of 2–4 × 106 PBMC resuspended in 100 µl of PBS containing 2% FCS, were treated with anti-CD16 (Leu 19, IgG1, clone MY31, Becton Dickinson) and anti-CD56 (Leu 11a, IgG1, clone 3G8, Becton Dickinson) during 30 min at 4°C and then with goat anti-mouse IgG-coated beads (Dynal, Oslo, Norway) (30 min) on an ice-cold bath. Cells were resuspended with PBS in a final volume of 2 ml and placed in a magnetic particle concentrator for 3 min to collect the unbound cells. The efficiency of the depletion as well as the percentage of the different lymphocyte subsets present in total PBMC and in the NK-depleted lymphocyte population (NK-depleted PBMC) was determined by flow cytometry. The percentage of CD16+/CD56+ lymphocytes in NK-depleted PBMC was 0–1%. NK-depleted PBMC were resuspended in complete medium ensuring that the proportion of the remaining cells was the same as in total cultured PBMC in order to compare their lytic activity. NK-depleted PBMC were incubated with hsp65 (10 µg/ml) in the presence of the cytokines mentioned above during 7 days and employed as effector cells.

Target cells

Monocytes were allowed to adhere to the bottom of 24 well flat bottom Falcon plates by incubation of PBMC (5 × 106/ml) for 2 h at 37°C. After removing nonadherent cells, cells remaining in the plates (10% of the original cell suspension) were incubated at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere for 7 days. For the cytotoxic assays, on day 6 of incubation, macrophages were pulsed with hsp65 (10 µg/ml). Macrophages kept under the same conditions but without addition of antigen were used as controls. Plates were cooled for 2 h at 4°C to facilitate the detachment of adherent cells by vigorous pipetting using ice-cold medium. These cells were washed and pellets of 5–7 × 105 cells were labelled with 100 µCi of Na251CrO4 (New England Nuclear, Boston, MA, USA) by incubation for 1 h at 37°C, after which they were washed three times and resuspended in complete medium at 1 × 105 cells/ml.

Cytotoxic assay

Five thousand target cells were seeded into each well of 96 well microtitre plates (Corning, USA). Effector cells (1 × 106 cells/ml) were added in triplicate at an effector to target cell ratio = 40 : 1 (E/T) in 0·25 ml final volume. The plates were centrifuged at 50 × g for 5 min and incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 4 h. After centrifugation at 500 × g for 5 min, 100 µl of supernatants was removed from each well. The radioactivity of supernatants and pellets was measured in a gamma counter. Results were expressed as percentage of cytotoxicity (% Cx):

Spontaneous release is the radioactivity released from target cells incubated with complete medium alone. It ranged from 8 to 15%. In all cases, the cytotoxic assays performed with PBMC cultured in the absence of hsp 65 or with macrophages not pulsed with antigen rendered negligible cytotoxicity (0–6%), even if cytokines were included in the cultures (2–7%). Data presented in Table and Figures were obtained by subtracting the cytotoxicity against nonhsp 65 pulsed macrophages from the experimental values determined using hsp 65-pulsed targets. PBMC were incubated during 7 days with LPS (E. coli 011:B4, Sigma), at the same concentration as endotoxin is present contaminating the hsp65 preparation. A negligible (1%-3%) cytotoxicity against hsp65-pulsed macrophages was observed.

Flow cytometric analysis of intracellular IFNγ production

In order to determine the effect of IL-18 and IL-13/anti-IL-13 on IFNγ production, PBMC (2 × 106 cells/ml in complete medium) were stimulated with hsp65 (10 µg/ml) in the presence or absence of IL-18 (10 ng/ml) with or without IL-13/anti-IL-13 (10 ng/ml) during 48 h at 37°C in 5% CO2. Monensin (3 µm, ICN, Biomedical Inc, Ohio, USA) was added to the PBMC cultures for the final 4 h of culture. Cells were washed and re-suspended in PBS supplemented with FCS (1%) and sodium azide (0·01%) (PBS-FCS-azide). Then, 100 µl of the cellular suspension was stained with anti-CD56-PE (Becton Dickinson) for 30 min at room temperature. Subsequently, cells were fixed (Fix and Perm, Caltag, Burlingame, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, after washing in PBS-FCS-azide, fixed cells were resuspended in 100 µl of PBS and an optimal dose of a fluorochrome conjugated antibody for intracellular staining (anti-human IFNγ FITC, Caltag) was added together with 100 µl permeabilizing solution (Fix and Perm, Caltag) and incubated for 30 min at 4°C, washed once with PBS-FCS-azide and finally resuspended in Isoflow solution. The samples were analysed in a FACScan cytometer using Cellquest software (Becton Dickinson). 50 000 events were acquired and analysed. Analysis gates were set on lymphocytes according to forward and side scatter properties. Results are expressed as the percentage of cytokine-producing cells in a population of specified cells. Cells labelled with isotype-matched irrelevant monoclonal antibodies and nonactivated lymphocytes labelled with anticytokine antibodies were used as controls.

Preparation of RNA

PBMC were cultured at 1 × 10 6/ml in complete culture medium and in the presence or absence of hsp65, with or without IL-18, IL-13 or anti-IL-13, at the concentration mentioned above, for 40 h. Then cells were spun and the pellets treated with Trizol (Life Technologies, USA). Total RNA was extracted as indicated by the manufacturer, finally dissolved in 50 µl of DEPC-treated water and the optical density of the resulting solution was determined in a Metrolab spectrophotometer (Metrolab, Argentina).

RT-PCR

Ten microlitres of each sample of RNA was used to obtain first strand cDNA by the use of Moloney leukaemia murine virus reverse transcriptase (MMLV-RT, Promega, USA) and oligo dT15 (Promega) as a primer. 10 µl of the cDNA obtained was used for PCR. The sequences of the primers used are: for β-actin sense: TGACGGGG TCACCCACACTGTGCCCATCTA and antisense: CTAGAAGCATTTGCGGTGGA CGATGGAGGG, and for IFN-γ: sense ATGAAATATACAAGTTATATCTTG GCTT T, antisense: GATGCTCTTCGACCTCGAAACAGCAT. A Perkin-Elmer thermocycler was used for amplification. The amplified fragments were analysed in a 10% polyacrylamide gel, electrophorized and stained with ethidium bromide. The stained gels were photographed with an FCR-10 camera (Fotodyne, WI, USA).

Statistics

Comparisons of MB, PB and N were performed using the Student’t test. Cytotoxicity values obtained from the different subsets of effector cells of each individual were compared using the Wilcoxon signed rank test.

RESULTS

Role of IL-18 on the generation of hsp65-induced CTL activity

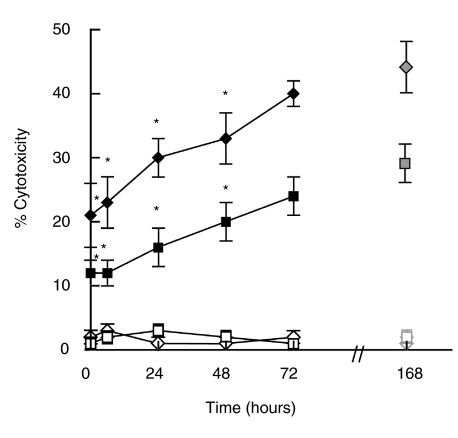

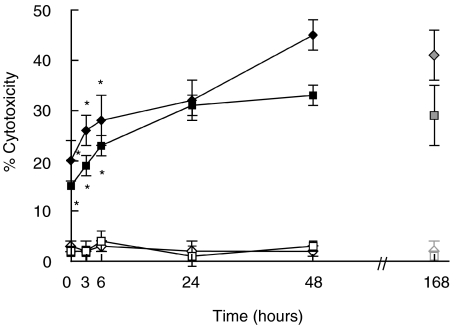

It is well known that IL-18 is an inductor of IFNγ[12,13] which is a key cytokine in the generation of hsp65-CTL response. In order to analyse whether IL-18 was involved in the development of hsp65-CTL, PBMC from PB patients and N controls were stimulated with M. leprae-derived hsp65 in the presence of neutralizing concentrations of anti-IL-18 MAb at the onset or at different time points throughout the subsequent culture period (168 h). As shown in Fig. 1, the lytic activity was inhibited when a-IL-18 was present either at the onset of the culture or added 24 h or 48 h after the antigen stimulation of PBMC from PB patients and N individuals in comparison to the cytotoxic activity generated in the absence of a-IL-18. The inhibition was dependent on the concentration of a-IL-18 added to the culture (data not shown). These results suggest that IL-18 plays an important role during the early and the late times of hsp65-CTL generation.

Fig. 1.

Inhibition of hsp65-induced cytotoxic activity by neutralization of endogenous IL-18. PBMC from 4 PB(⋄) and 4 N (▪) were cultured for 7 days with hsp65 (168 h, ◊ and □) or hsp65 and anti-IL18 (⋄ and ▪) added at the onset (0 h) or at different time points (6 h, 24 h, 48 h or 72 h) after the beginning of the culture. Then cells were tested for their lytic activity against hsp65-pulsed (⋄, ▪) or non pulsed macrophages (◊, □) as mentioned in Materials and methods. Results are expressed as % cytotoxicity (mean ± SEM). Statistical differences between % cytotoxicity from hsp65 stimulated PBMC and % cytotoxicity from anti-IL-18 treated and hsp65 stimulated PBMC: * P < 0·05.

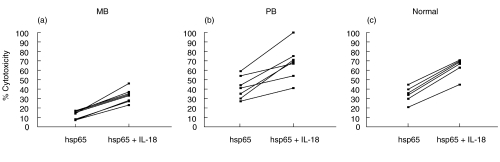

Low expression of mRNA coding for IL-18 has been reported in M. leprae stimulated adherent cells as well as in lesions from lepromatous patients [23] along with low levels of IL-12, likely contributing to the weak cell mediated immunity observed in these patients. So, we analysed whether the lack of hsp65-CTL activity observed in MB patients could be reverted by addition of IL-18 during the stimulation of PBMC with hsp65. As shown in Fig. 2, hsp65-CTL of MB patients was significantly increased when IL-18 was added at the onset of antigen stimulation (P < 0·005). In addition, comparison of CTL responses from leprosy patients early or late during MDT treatment showed no significant changes (data not shown). An increase was also observed in cells from PB patients (P < 0·01) and N controls under the same conditions (P < 0·005).

Fig. 2.

Effect of exogenous IL-18 on the generation of hsp65-induced cytotoxic activity. PBMC from (a) 11 MB, (b) 7 PB patients and (c) 6 N controls were incubated during 7 days with hsp65 in the presence or absence of IL-18 and then tested for their ability to lyse hsp65-pulsed macrophages. Results are expressed as % cytotoxicity and individual data are shown.

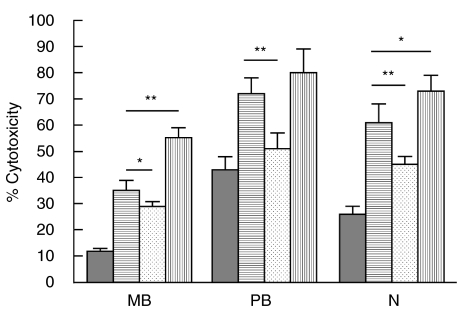

The effect of IL-18 on hsp65 cytotoxic response is partially mediated by IL-12

It has been reported that IL-18 modulates T-cell effector functions through the action of IL-12 [24], which is considered to play an important role in the generation of hsp65-CTL activity [25]. Therefore, in order to analyse whether the increase observed in hsp65-CTL activity by IL-18 was also dependent on IL-12, PBMC from leprosy patients and N controls were incubated with hsp65 and IL-18 in the presence of a neutralizing concentration of an a-IL-12 MAb to block the activity of endogenous IL-12. As shown in Fig. 3, a-IL-12 partially inhibited the positive effect of IL-18 on the generation of hsp65-CTL activity in all the groups studied, suggesting that IL-18 enhanced the cytotoxic response via both an IL-12 dependent and an IL-12 independent pathways. Furthermore, experiments performed employing IL-18 plus IL-12 showed that the coaddition of these two cytokines markedly increased the hsp65-CTL activity in MB and N (Fig. 3) confirming that these two cytokines collaborate in the generation of the hsp65-induced cytotoxic effector cells.

Fig. 3.

IL-18 acts in an IL-12-dependent and IL-12-independent manner on the generation of hsp65-induced CTL activity. PBMC from 11 mB, 7 PB patients and 6 N controls were cultured during 7 days with hsp65, in the absence ( ) or presence of IL-18 (

) or presence of IL-18 ( ), IL-18 + anti-IL-12 MAb (

), IL-18 + anti-IL-12 MAb ( ) or IL-18 + IL-12 (

) or IL-18 + IL-12 ( ). Then cells were tested for their lytic activity against hsp65-pulsed macrophages. Results are expressed as percentage of cytotoxicity (mean ± SEM). *P < 0·05, **P < 0·02.

). Then cells were tested for their lytic activity against hsp65-pulsed macrophages. Results are expressed as percentage of cytotoxicity (mean ± SEM). *P < 0·05, **P < 0·02.

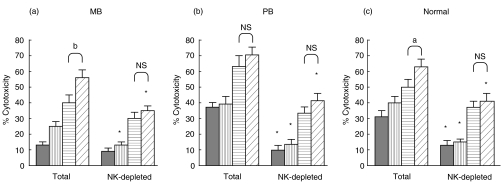

IL-18 enhanced hsp65-induced CTL by acting on CD3+ and CD56+/CD16+ NK cells

To identify the populations of cells that respond to IL-18, depletion of CD56+/CD16+ cells was performed in PBMC and then, total and NK-depleted PBMC were stimulated with hsp65 in the presence of IL-18, IL-12 or IL18 + IL-12. As shown in Fig. 4, the depletion of CD56+/CD16+ cells previous to antigen stimulation abrogated the cytolytic activity in cells from PB and N controls. Besides, in these cells IL-12 could not up-regulate the generation of hsp65-CTL effector cells when NK cells were either present or absent during antigen stimulation. In contrast, IL-18 was able to increase the lytic activity despite the absence of NK cells, although to a lesser extent than that observed in total PBMC, in the three groups tested. Moreover, no differences were observed in hsp-65 CTL activity in MB, PB and N when IL-12 was added to the IL-18 treated cells in NK-depleted cells. In addition, depletion of NK cells 24 h after the onset of antigen stimulation did not inhibit the generation of hsp65-CTL activity (data not shown). These results suggest that IL-18 enhances CTL activity through direct action on CD3+ T and NK cells. In the presence of NK cells this positive effect can be amplified at the early steps of the culture through an IL-12 dependent mechanism.

Fig. 4.

IL-18 enhanced hsp65-induced CTL by acting on both T lymphocytes and CD56+/CD16+ NK cells. PBMC from (a) 6 MB, (b) 6 PB patients and (c) 5 N controls were depleted (NK-depleted PBMC) or not (Total PBMC) of CD56+/CD16+ NK cells by magnetic methods as described in Material and Methods. Both cell populations were cultured during 7 days with hsp65 in the presence or absence of cytokines (▪ PBMC + hsp65;  PBMC + hsp65 + IL-12;

PBMC + hsp65 + IL-12;  PBMC + hsp65 + IL-18;

PBMC + hsp65 + IL-18;  PBMC + hsp65 + IL-12 plus IL-18) and then tested for their lytic activity against hsp65-pulsed macrophages. Results are expressed as percentage of cytotoxicity (mean ± SEM). Statistical differences between % cytotoxicity from the equivalent Total/undepleted PBMC and NK-depleted PBMC (cultured in the same conditions of antigen and cytokines):*P < 0·05; % cytotoxicity from PBMC + IL-18 + IL-12 versus% of cytotoxicity from PBMC + IL-18: a, P < 0·05; b, P < 0·02; NS = no statistical significant.

PBMC + hsp65 + IL-12 plus IL-18) and then tested for their lytic activity against hsp65-pulsed macrophages. Results are expressed as percentage of cytotoxicity (mean ± SEM). Statistical differences between % cytotoxicity from the equivalent Total/undepleted PBMC and NK-depleted PBMC (cultured in the same conditions of antigen and cytokines):*P < 0·05; % cytotoxicity from PBMC + IL-18 + IL-12 versus% of cytotoxicity from PBMC + IL-18: a, P < 0·05; b, P < 0·02; NS = no statistical significant.

Inhibition by IL-13 of hsp65-induced cytotoxic activity

IL-18 may be a cofactor for the development of humoral immunity and is a coinducer of IL-13 in NK and T cells when IFNγ is suppressed [16]. In addition, a subset of NK cells that produces IL-13 and is able to regulate IFNγ production has been recently identified [26]. Thus we analysed the effect of IL-13 on the generation of hsp65-induced CTL effector cells. As shown in Fig. 5, addition of IL-13 to PBMC from PB patients and N controls at the onset or 6 h after antigen stimulation inhibited the generation of hsp65 cytotoxic activity when compared with that obtained in the absence of IL-13. Addition of this cytokine, 24 h after hsp65 stimulation inhibited the hsp65-induced CTL only in 2 out 5 PB while no inhibition was observed in the cytotoxic response of N controls. Moreover, a small increase of the lytic activity was observed in cells from 3 out 5 PB studied when IL-13 was added 48 h after antigen stimulation. Therefore, IL-13 strongly modulates the early stages of CTL generation.

Fig. 5.

Inhibition of hsp65-induced CTL activity by exogenous IL-13: PBMC from 5 PB (⋄) patients and 5 N controls (▪) were cultured during 7 days with hsp65 (168 h, ◊ and □) or hsp65 and IL-13 (⋄ and ▪) added at the onset (0 h) or at different time points (3 h, 6 h, 24 h or 48 h) along the culture period. Then cells were tested for their lytic activity against hsp65-pulsed (⋄, ▪) or non pulsed macrophages (◊, □). Results are expressed as % cytotoxicity (mean ± SEM). Statistical differences between % cytotoxicity from hsp65 stimulated PBMC and % cytotoxicity from IL-13 treated and hsp65 stimulated PBMC: *P < 0·05.

Considering the low hsp65 lytic activity generated both in the presence or absence of NK cells in PBMC from MB patients, we undertook to determine whether endogenous IL-13 could be involved in the early stages of CTL development. As it can be observed in Table 1, neutralization of IL-13 at the onset of antigen stimulation increased the hsp-65 cytotoxic response and, even more, when CTL were generated in the presence of IL-18 an enhancing effect was observed in the lytic activity. On the other hand, in cells from PB and N, addition of IL-13 at the onset of antigen stimulation inhibited hsp65-CTL activity and decreased the enhancing effect of IL-18. These results demonstrate that when IL-13 is present at the beginning of antigen stimulation the CTL generation is down regulated and, also, that the positive effect of IL-18 on hsp65-CTL activity can be suppressed by IL-13. In cells from MB patients neutralization of IL-13 results in an increase of the hsp65 induced cytotoxic activity suggesting the production of IL-13 probably by an NK cell subpopulation since the down modulatory effect of IL-13 was observed at very short times after antigen stimulation.

Table 1.

Effect of IL-13 on the hsp65-induced CTL activity

| PBMC from | n | PBMC coincubated with | PBMC + hsp65 % cytotoxicity | PBMC + hsp65 + IL-18 % cytotoxicity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MB | 10 | – | 12 ± 1 | 38 ± 4 |

| anti-IL-13 | 28 ± 2* | 52 ± 3* | ||

| PB | 7 | – | 43 ± 6 | 68 ± 7 |

| IL-13 | 19 ± 3* | 39 ± 7* | ||

| N | 7 | – | 27 ± 2 | 58 ± 6 |

| IL-13 | 10 ± 2* | 39 ± 7* |

PBMC from MB, PB patients and N individuals were incubated during 7 days with hsp65 or IL-18 in the presence or absence of anti-IL-13 or IL-13. Cells were then employed as effector cells in the cytotoxic assay. Results are expressed as percentage of cytotoxicity (mean ± SEM). Statistical differences between % cytotoxicity from PBMC cultured in the absence of IL-13 and percentage of cytotoxicity from PBMC cultured with IL-13

P < 0·05.

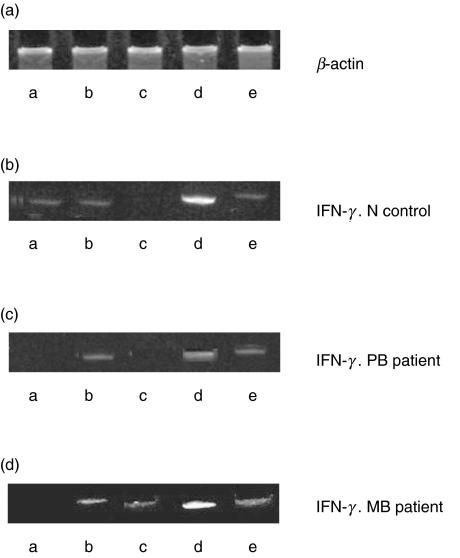

Modulation by IL-18 and IL-13 of the IFNγ mRNA induction in PBMC

In order to investigate whether the increase in hsp65-CTL activity could be associated to an induction of mRNA coding for IFNγ in cells from leprosy patients and N controls, and could be modulated by IL-18 and IL-13, we performed a series of RT-PCR experiments. Although some induction could be observed at 40 h with hsp65 in cells from 3 out 10 individuals studied (1 out of 2 PB, 1 out of 3 N and 1 out of 5 mB), when stimulation occurred in the presence of IL-18 an intense band for IFNγ could be observed when PBMC from all the groups were analysed. In the MB example shown in Fig. 6 the band corresponding to IFNγ was less intense when anti-IL-13 was added alone or even in the presence of IL-18. In two other MB cases a band for IFNγ was observed only with the simultaneous addition of hsp65, IL-18 and anti-IL-13 (data not shown). In PBMC from PB patients and N controls IL-13 inhibited the expression of mRNA coding for IFNγ. This inhibition was overcome in the presence of IL-18 recovering basal levels (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Effect of IL-18 and IL-13 on the expression of mRNA coding for IFNγ in PBMC. (a) β-actin; (b) N control; (c) PB patient; (d) MB patient. PBMC were cultured in complete medium alone (lane a) or in the presence of M. leprae hsp65 (lane b), hsp65 + IL-13 (lane c, N and PB) or anti-IL-13 (lane c MB), hsp65 + IL-18 (lane d) or hsp65 + IL-13 + IL-18 (lane e N and PB) or hsp65 + anti-IL-13 + IL-18 (lane e MB) and then RT-PCR was performed as described in Material and methods. One representative experiment of each group studied is shown.

Hence hsp65 induces mRNA coding for IFNγ only in some individuals and IL-13 can inhibit the expression of this mRNA. Treatment with anti-IL-13, at least at the antibody concentration tested, does not increase the stimulatory effect of IL-18 on IFNγ mRNA expression.

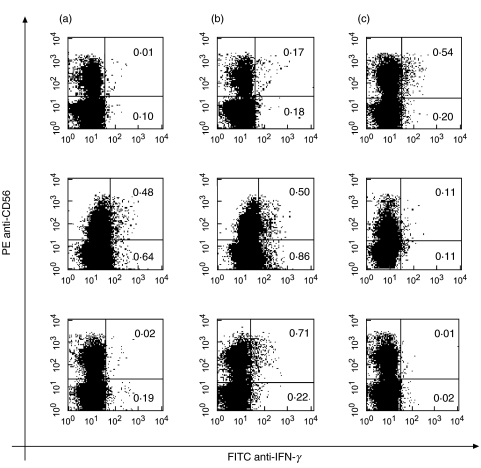

Effect of IL-18 and IL-13 on IFNγ production by CD56+ cells to hsp65

Considering the fact that both IL-18 and IL-13 act on NK cells and can modulate the expression of mRNA coding for IFNγ, we undertook to determine their effect on IFNγ production by CD56+ and CD56– cell populations. For this purpose PBMC were stimulated with hsp65 in the presence of IL-18 and anti-IL-13 in cell cultures from MB patients or IL-13 in cells from PB patients and N, during 72 h and then stained for surface CD56 and intracellular IFNγ expression. As shown in Fig. 7, the lower percentages of IFNγ+ CD56+ and CD56– cells were observed in MB patients in response to hsp65, while, IFNγ+ CD56+ and CD56– cells can be detected in PB patients. An increase in IFNγ+ cells was observed in both subpopulations from patients in the presence of IL-18, although it was much smaller in CD56 + cells from PB patients known to produce IFNγ in response to M. leprae antigens. Moreover, in the presence of IL-18, neutralization of IL-13 increased the percentage of IFNγ+ CD56+ in MB patients while addition of IL-13 reduced the IFNγ+ CD56+ and CD56–cells in PB patients and N. These results confirm that in response to hsp65, IL-18 enhances and IL-13 down modulates the IFNγ production of CD56+ cells. This early produced IFNγ by CD56 + cells can in turn induce further production of the same cytokine by CD56- (mainly CD3+) cells later on.

Fig. 7.

Effect of IL-18 and IL-13 on hsp65-induced IFNγ production by CD56– and CD56+ cells. PBMC from 4 mB and 3 PB patients and 3 N controls were cultured during 3 days with hsp65 (a), hsp65 + IL-18 (b) or hsp65 + IL-18 plus anti-IL-13 or IL-13 (anti-IL-13 in MB and IL-13 in PB patients and N) (c). Then cells were stained with anti-CD56-PE and anti-IFNγ-FITC as described in Material and Methods. Results are expressed as the percentage of IFNγ-producing CD56+ and CD56– cells. One representative experiment of each group is shown.

DISCUSSION

Specific unresponsiveness to M. leprae antigens is a feature of MB patients. We have previously demonstrated that cells from MB patients were unable to generate a cytotoxic T cell response when hsp65 was employed as antigen [20]. IFNγ is one of the key cytokines involved in the hsp65 CTL response [27] and this response is amplified by addition of IL-12, generating CD56+ effector cells [25] in PBMC from leprosy patients. In the present report we evaluated the role of both IL-18 and IL-13. It is well known that both IL-18 and IL-12 are able to induce the production of IFNγ from NK and T cells [7,28]. In addition, mRNA coding for IL-18 and IL-12 has been observed in cells from leprosy lesions and in adherent PBMC from tuberculoid leprosy patients, suggesting that the presence of these two cytokines correlates with the level of cell mediated immunity observed in these patients [23,29]. Our results show that IL-18 is required during the first 48–72 h, a time longer than IL-12 (24 h) for the generation of hsp65 CTL [25] and that, as well as IL-12, it increases the cytotoxic activity in cells from leprosy patients and normal controls. Moreover, in our experimental model, IL-18 is a powerful inductor of hsp65 CTL in PBMC from MB patients, in contrast to the results reported for M. leprae induced proliferation [23]. This discrepancy may be due to differences in the antigen used and/or the effector function evaluated. The stimulatory effect of IL-18 was in part mediated by IL-12 both in patients and N controls. Since IL-18 and IL-12 synergistically induce IFNγ production by NK, T and B cells [7,23,28,30] the decrease in the lytic activity observed by neutralization of endogenous IL-12 during CTL development could be due to a reduced production of IFNγ, as described for M. leprae[23]. In the present report we have demonstrated that IL-18 and IL-12 collaborate in the induction of hsp-65 cytotoxic response in patients and N controls. Therefore, as reported with experimental M. leprae[31] and M. avium[32,33] infection in mice, IL-18 is important for the generation of protective immunity to mycobacteria.

It is well known that IL-18 acts on both NK and T cells. In our experimental system, we observed that when NK cells were present at the onset of the hsp65 stimulation, higher cytotoxic activity was generated from PBMC of PB patients than from cells of MB in response to exogenous IL-18, but similar cytotoxic responses were generated in NK-depleted PBMC obtained from the two groups of patients, suggesting that in the absence of NK cells IL-18 can act directly on T cells, and that NK cells can amplify the positive effect of IL-18. In opposition, the stimulatory effect of IL-12 on hsp65-CTL generation required the presence of NK cells since the increase was not observed when NK cells were depleted. As CD56– (mainly CD3+) cells from MB patients can respond to exogenous IL-18 in a way similar to NK depleted cells from PB patients, we can assume that NK cells from MB patients are not able to efficiently amplify the positive effect of IL-18, probably because they produce type 2 cytokines which could be responsible for the differences observed in the CTL response.

It is known that NK cells produce both type 1 and type 2 cytokines [34]. They direct the development of the antigen-specific T cell-mediated response to intracellular pathogens via IFNγ, contributing to control Th1 cell differentiation through the release of IL-12 [2,35]. IL-13 is produced predominantly by CD4+ Th2 cells although increased IL-13 levels produced by NK cells have been observed in IFNγ deficient mice [16]. Clones producing both cytokines were described in humans [16] and recently, two nonoverlapping IL-13+ and IFNγ+ subsets were identified in adult and neonatal human NK cells [26]. In vitro, IL-13 is a macrophage-deactivating agent because it inhibits the production of cytokines, nitric oxide, and chemokines such as MIP-1α and IL-8 [19,36–38]. In vivo, IL-13 inhibits TNFα release and neutrophil accumulation [39,40]. In addition, it has been demonstrated that IL-13 was coproduced dominantly along with IL-4 by type 2-like M. leprae-responsive T cell clones generated from borderline lepromatous patients [41]. However, unlike IL-4, IL-13 lacks the capacity to induce type 2 differentiation because, although IL-4 and IL-13 share the alpha receptor chain, T cells lack functional IL-13 receptors [36]. We observed that the presence of IL-13 at the onset of antigen stimulation, reduced the lytic activity generated in cells from PB and N controls. This inhibitory effect was not observed when IL-13 was added later, which suggests that it might be affecting the early production of IFNγ. Moreover, this negative effect of IL-13 on the generation of hsp65 cytotoxic activity was also observed in the presence of IL-18, concomitantly with a decrease in the percentage of IFNγ+ CD56+ and CD56– cells and a diminution in the level of IFNγ mRNA observed in PBMC from PB and N controls. Conversely, neutralization of endogenous IL-13 in MB patients increased the hsp65 lytic activity to levels over those observed when IL-18 was added. Even more, this enhancing effect correlated with an increase in IFNγ+ CD56+ cells and detectable levels of mRNA coding for IFNγ in cells from MB patients. IL-4, involved in the development of hsp-65-CTL [25], is one of the Th2 cytokines found in lesions from multibacillary leprosy patients [10,11]. Its presence may result in accumulation of IL-13+ NK cells, due to an impaired maturation of NK cells or to a loss of IFNγ producing NK cells. Lack of IFNγ produced by CD56 + cells in early times of the response would account for an inadequate production of the same cytokine by CD56– (mainly CD3+) cells later on, resulting in the deficient hsp-65-CTL response observed in MB patients. Therefore, our results imply that IL-13 is a strong inhibitory cytokine that can modulate the early and late steps of hsp65-CTL generation by diminishing IFNγ production, and probably also that of TNFα, in MB patients.

In conclusion, our results demonstrate that NK cells modulate the hsp65-CTL generation in leprosy patients. IL-18 increases the lytic activity in NK-depleted PBMC from MB patients proving that NK cells act as negative regulators in hsp65 CTL activity. The down modulation induced on the generation of lytic activity by IL-13 is observed at early time points suggesting that IL-13 affects IFNγ production by NK cells. This effect of IL-13 may account in part for the unresponsiveness observed in MB patients.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (CONICET, PIP 0711/98), Agencia Nacional de Promoción Científica y Tecnológica (ANPCyT, 05–04816).

REFERENCES

- 1.Young HA, Hardy KJ. Role of IFNγ in immune-cell regulation. J Leuk Biol. 1995;58:373–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Trinchieri G. Interleukin-12: a proinflammatory cytokine with immuno-regulatory functions that bridge innate resistance and antigen-specific adaptative immunity. Annu Rev Immunol. 1995;13:251–76. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.13.040195.001343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ma X, Chow JM, Gri G, Garra G, Gerosa F, Wolf SF, Dzialo R, Trinchieri G. The interleukin 12 p40 gene promoter is primed by interferon gamma in monocytic cells. J Exp Med. 1996;183:147–57. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.1.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.D’Andrea A, Ma X, Aste Amezaga M, Paganin C, Trinchieri G. Stimulatory and inhibitory effects of IL-4 and IL-13 on the production of cytokines by human peripheral blood mononuclear cells: priming for IL-12 and tumor necrosis factor α production. J Exp Med. 1995;181:537–46. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.2.537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.D’Andrea A, Rengaraju M, Valiante NM, et al. Production of natural killer cells stimulatory factor (Interleukin-12) by peripheral blood mononuclear cells. J Exp Med. 1992;176:1387–98. doi: 10.1084/jem.176.5.1387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Okamura H, Tsutsui H, Komatsu T, et al. Cloning of a new cytokine that induces IFN-γ production by T cells. Nature. 1995;378:88–91. doi: 10.1038/378088a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Okamura H, Kashiwamura SI, Tsutsui H, Yoshimoto T, Nakanishi K. Regulation of interferon-γ by IL-12 and IL-18. Curr Opin Immunol. 1998;10:259–64. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(98)80163-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bancroft GJ, Sheehan KC, Schreiber RD, Unanue ER. Tumour necrosis factor is involved in the T cell-independent pathway of macrophage activation in scid mice. J Immunol. 1989;143:127–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hunter CA, Timans J, Pisacane P, et al. Comparison of the effects of interleukin-1α, interleukin 1-β and interferon-γ-inducing factor on the production of interferon-γ by natural killer. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:2787–92. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830271107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yamamura M, Uyemura K, Deans RJ, Weinberg K, Rea TH, Bloom BR, Modlin RL. Defining protective responses to pathogens: cytokine profiles in leprosy lesions. Science. 1991;254:277–9. doi: 10.1126/science.254.5029.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yamamura M, Wang XH, Ohmen JD, Uyemura K, Rea TH, Bloom BR, Modlin RL. Cytokines patterns of immunological mediated tissue damage. J Immunol. 1992;149:1470–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nakanishi K, Yoshimoto T, Hiroko T, Okamura H. Interleukin-18 regulates bothTH1 and TH2 responses. Ann Rev Immunol. 2001;19:423–74. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Akira S. The role of IL-18 in innate immunity. Curr Opin Immunol. 2000;12:59–63. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(99)00051-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hyodo Y, Matsui K, Hayashi N, et al. IL-18 upregulates perforin-mediated NK activity without increasing perforin messenger RNA expression by binding constitutively expressed IL-18 receptor. J Immunol. 1999;162:1662–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moretta L, Bottino C, Pende D, Mingari MC, Blassoni R, Moretta A. Human natural killer cells. their origin, receptors and function. Eur J Immunol. 2002;32:1208–11. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200205)32:5<1205::AID-IMMU1205>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoshino T, Wiltroout RH, Young HA. IL-18 a potent co-inducer of IL-13 in NK and T cells: a new potential role for IL-8 in modulating the immune response. J Immunol. 1999;162:5070–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Vries JE. Molecular and biological characteristics of Interleukin-13. Chem Immunol. 1996;63:204–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.YuCh R, Kirken RA, Malabarba MG, Young HA, Ortaldo JR. Differential regulation of the Janus Kinase-STAT pathway and biologic function of IL-13 in primary human NK and T cells: a comparative study with IL-4. J Immunol. 1998;161:218–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de Waal Malefyt R, Figdor CG, Huijbens R, et al. Effects of IL-13 on phenotype, cytokine production, and cytotoxic function of human monocytes. Comparison with IL-4 and Modulation by IFN-Gamma or IL-10. JImmunol. 1993;151:6370–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de la Barrera S, Fink S, Finiasz M, Minucci F, Valdez R, Baliña LM, Sasiain MC. Lack of cytotoxicity against Mycobacterium leprae-65 kD heat shock protein (hsp) in multibacillary leprosy patients. Clin Exp Immunol. 1995;99:90–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1995.tb03477.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ridley DS, Jopling WH. Classification of leprosy according to immunity: a five group system. Int J Lepr. 1996;34:255–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boyum A. Isolation of mononuclear cells and granulocytes from human blood. Scand J Clin Invest. 1968;97:77–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garcia V, Uyemura K, Sieling P, et al. IL-18 promotes type 1 cytokine production from NK cells and T cells in human intracellular infection. J Immunol. 1999;162:6114–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yoshimoto T, Takeda K, Tanaka T, Ohkusu K, Kashiwamura S, Okamura H, Akira S, Nakanishi K. IL-12 up-regulates IL-18 receptor expression on T cells, Th1 cells, B cells: synergism with IL-18 for IFN-γ production. J Immunol. 1998;161:3400–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alemán M, de la Barrera S, Fink S, Finiasz M, Fariña MH, Pizzariello G, Sasiain MC. Interleukin-12 amplifies the M.leprae hsp65-cytotoxic response in the presence of Tumour necrosis factor-α and Interferon-γ generating CD56+ effector cells: Interleukin-4 down-regulates this effect. Scand J Immunol. 2000;51:262–70. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.2000.00675.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Loza MJ, Peters S, Zangrilli JG, Perussia B. Distinction between IL13+ and IFN-γ+ natural killer cells and regulation of their pool size by IL-4. Eur J Immunol. 2002;32:413–23. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200202)32:2<413::AID-IMMU413>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sasiain MC, de la Barrera S, Fink S, Finiasz M, Alemán M, Fariña MH, Pizzariello G, Valdez R. Interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) and tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNFα) are necessary in the early stage of induction of CD4 and CD8 cytotoxic T cells by Mycobacterium leprae heat-shock protein (hsp) 65 kD. Clin Exp Immunol. 1998;114:196–203. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1998.00702.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang T, Kawakami T, Qureshi MH, Okamura H, Kurimoto M, Saito A. Interleukin-12 (IL-12) and IL-18 sinergistically induce the fungicidal activity of murine peritoneal exudate cells against Criptococcus neoformans through production of γ interferon and natural killer cells. Infect Immun. 1997;65:3594–9. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.9.3594-3599.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yamauchi P, Bleharski JR, Uyemura K, et al. A role for CD40–CD40L ligand interactions in the generation of type 1 cytokine responses in human leprosy. J Immunol. 2000;165:1506–12. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.3.1506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Micallef MJ, Ohtsuki T, Kohno K, et al. Interferon-γ inducing factor enhances T helper 1 cytokine production by stimulated human T cells: synergism with interleukin-12 for interferon-γ production. Eur J Immunol. 1996;26:1647–51. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830260736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kobayashi K, Kai M, Gidoh M, Nakata N, Endoh M, Singh RP, Kasama T, Saito H. The possible role of interleukin (IL)-12 and interferon-gamma-inducing factor/IL-18 in protection against experimental Mycobacterium leprae infection in mice. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1998;88:226–31. doi: 10.1006/clin.1998.4533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Takeda K, Tsutsui H, Yoshimoto T, et al. Defective NK cell activity and Th1 response in IL-18-deficient mice. Immunity. 1998;8:383–90. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80543-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kobayashi K, Nakata N, Kai M, Kasama T, Hanyuda Y, Hatano Y. Decreased expression of cytokines that induce type 1 helper T cell/interferon-gamma responses in genetically susceptible mice infected with Mycobacterium avium. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1997;85:112–6. doi: 10.1006/clin.1997.4421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peritt D, Robertson S, Gri G, Showe L, Aste-Amezaga M, Trinchieri G. Cutting edge. Differentiation of human NK cells into NK1 and NK2 subsets. J Immunol. 1998;161:5821–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tay CH, Szolomolanyi E, Welsh RM. Control of infections by NK cells. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1998;230:193–220. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-46859-9_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zurawski G, de Vries JE. Interleukin 13, an interleukin 4-like cytokine that acts on monocytes and B cells, but not on T cells. Immunol Today. 1994;15:19–26. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(94)90021-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Doherty TM, Kastelein R, Menon S, Andrade S, Coffman RL. Modulation of murine macrophage function by IL-13. J Immunol. 1993;151:7151–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ohta TM, Kasama T, Hanyuuda M, Hatano Y, Kobayashi K, Negishi M, Ide H, Adachi M. Interleukin-13 down-regulates the expression of neutrophil-derived macrophage inflammatory protein-1 alpha. Inflamm Res. 1998;47:361–8. doi: 10.1007/s000110050345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Watson ML. Anti-inflammatory actions of interleukin-13: suppression of tumor necrosis factor-alpha and antigen-induced leukocyte accumulation in the guinea pig lung. Am J Resp Cell Mol Biol. 1999;20:1007–12. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.20.5.3540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Matsukawa A, Hogaboam CM, Lukacs NW, Lincoln PM, Evanoff HL, Strieter RM, Kunkel SL. Expression and contribution of endogenous IL-13 in an experimental model of sepsis. J Immunol. 2000;164:2738–44. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.5.2738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Verhagen CE, van der Pouw Kraan TC, Buffing AA, Chand MA, Faber WR, Aarden LA, Das PK. Type 1- and type 2-like lesional skin-derived Mycobacterium leprae-responsive T cell clones are characterized by co-expression of IFN-gamma/TNF-alpha and IL-4/IL-5/IL-13, respectively. J Immunol. 1998;160:2380–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]