Abstract

To examine the effects of anti-CD4 mAb treatment in acute and chronic antigen-induced arthritis (AIA), C57BL/6 mice were treated intraperitoneally either with the depleting anti-CD4 mAb GK1·5 or with rat-IgG (control) on Days −1, 0, 1, 3, 5, and 7. Arthritis was monitored by assessment of joint swelling and histological evaluation in the acute (Day 3) and the chronic phase (Day 21) of AIA. To determine the effects on cellular immune responses, in vivo T-cell reactivity (delayed type hypersensitivity; DTH) was measured, as well as protein levels of TH1- (IL-2, IFN-γ) and TH2-cytokines (IL-4, IL-10) in joint extracts and supernatants of ex vivo stimulated spleen and lymph node cells. The humoral immune response was analysed by measuring serum antibodies against methylated bovine serum albumine (mBSA) and extracellular matrix proteins. Treatment with GK1·5 reduced swelling, inflammation, and destruction of the arthritic joint. Unexpectedly, the effects were even more pronounced in the acute than in the chronic phase. The anti-inflammatory effect was accompanied by a diminished DTH against the arthritogen mBSA and a decrease of TH1-cytokine production in spleen and pooled body lymph nodes, whereas the TH2-cytokine production in these organs was unchanged and the humoral immune response was only moderately reduced. There was a failure of depleting CD4+ T-cells in the joint, reflected also by unchanged local cytokine levels. Therefore, systemic rather than local effects on the TH1/TH2 balance appear to underlie the therapeutic efficacy of anti-CD4 treatment in AIA.

Keywords: Acute, anti-CD4 mAb, antigen-induced arthritis, chronic, T helper cell

INTRODUCTION

CD4+ T-helper cells infiltrate the synovial membrane during the development of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) [1] and are found in synovial lymphoid aggregates during the chronic, destructive phase [2]. For this reason and because of beneficial effects of treatments directed against CD4+ T-cells [3], these cells presumably play a central role in promoting human RA (reviewed in [4,5]).

Antigen-induced arthritis (AIA) is an intensely studied animal model of arthritis. It shows similarities with human RA with respect to histopathological features, response to antirheumatic drugs [6], and inducibility of acute flares upon repeated antigen challenge [7,8]. AIA is induced by systemic immunization with methylated bovine serum albumin (mBSA) in complete Freund's adjuvant, followed by an injection of mBSA into the joint cavity. After an acute inflammatory reaction, considered to be mediated by the resulting immune complexes of antigen and specific antibodies [9], formation of the so-called pannus leads to chronic, destructive arthritis.

In AIA, T-cells are clearly important for progression of AIA, because preventive treatment with an anti-TCRα/β monoclonal antibody (mAb) completely blocks the occurrence of chronic ovalbumin-induced AIA and diminishes clinical signs if given in the early chronic phase [10]. Also, successful treatment of established AIA with immuno-suppressants that selectively inhibit T-cell functions [11,12] clearly shows that this model is T-cell dependent. CD4+ T-cells play a substantial role also in AIA flare-up reactions, as demonstrated by blocking exacerbations of joint swelling, inflammation, and destruction in mice treated with the anti-CD4 mAb GK1·5 before antigen rechallenge [13]. Indirect evidence for participation of CD4+ T-cells in the inducing phase of disease derives from adoptive transfer experiments with CD4+ T-cell-depleted spleen and lymph node cells in SCID mice, resulting in significantly reduced disease activity [14]. However, it remains unclear whether CD4+ T-cells are critical in the early phase of AIA, in addition to the well-known immune complex mechanism.

Therefore, mice were treated with the depleting anti-CD4 mAb GK1·5 [15] prior to AIA induction (Day −1, 0), during the acute phase (Days 1, 3, 5) and the early chronic phase (Day 7) of AIA. Mechanisms underlying the resulting effects on joint swelling, synovial inflammation, and destruction of bone and cartilage were investigated by determining in vivo T-cell reactivity (delayed type hypersensitivity; DTH), cytokine profiles of lymphoid organs and joints, and humoral response to mBSA and matrix antigens. A clear therapeutic effect of anti-CD4 treatment was observed in the acute phase of AIA; unexpectedly, this effect was even more pronounced in acute than in chronic AIA, underlining the essential role of CD4+ T-cells in the acute phase of experimental arthritis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and antibodies

Female C57BL/6 mice, 8–10 weeks of age, were obtained from the Animal Research Facility, Friedrich Schiller University, Jena, Germany. They were kept under standard conditions, 10 per cage with food and water ad libitum and a 12 h/12 h light/dark cycle. All animal studies were approved by the governmental commission for animal protection. The rat-antimouse CD4 mAb GK1·5 (IgG2b) was purified from hybridoma (GK1·5; ATCC TIB-207, Manassas, VA, USA) culture supernatant, the control rat IgG from Lewis rat serum, both by affinity chromatography on HiTrap Protein-G columns (Amersham-Pharmacia, Freiburg, Germany).

Antigen-induced arthritis and anti-CD4 treatment

The animals were immunized on Days − 21 and − 14 by subcutaneous injection of 100 µg methylated bovine serum albumin (mBSA) in 50 µl saline, emulsified in 50 µl complete Freund's adjuvant (Sigma, Deisenhofen, Germany) which was adjusted to 2 mg/ml with heat-killed Mycobacterium tuberculosis (strain H37RA; Difco, Detroit, MI, USA). In addition, the mice received an intraperitoneal injection of 2 × 109 heat-inactivated Bordetella pertussis (Pertussis Reference Centre, Krankenhaus Friedrichshain, Berlin, Germany). Arthritis was elicited on Day 0 by injection of 100 µg mBSA in 25 µl saline into the right knee joint cavity, while the left knee remained untreated. For anti-CD4 treatment, the mice (n = 10) received 200 µg of the antimouse CD4 mAb GK1·5 on Days −1, 0, 1, 3, 5, and 7 of AIA intraperitoneally. The control group (n = 10) was treated with 200 µg rat IgG instead. Joint swelling was measured on Days 0, 1, 3, 5, 7, 14, and 21 using an Oditest vernier calliper (Kroeplin Längenmesstechnik, Schlüchtern, Germany) and expressed as the difference between the diameter of the right and the left knee joint.

Delayed type hypersensitivity

For assessment of DTH, 10 µl mBSA-solution (0·5 mg/ml in 0·9% saline) were injected intradermally into the pinna of the right ear on Day 5. The thickness of the ear was measured before injection and 24 and 48 h later by a vernier calliper and expressed as the difference between the mean thickness of the ear after 24 and 48 h and the initial thickness of the ear.

Histology

Both knee joints were removed on Day 3 (acute phase) or on Day 21 (late chronic phase) of AIA, skinned, and fixed in phosphate-buffered formalin. Paraffin sections of EDTA-decalcified joints (5 µm) were stained with haematoxylin/eosin. Severity of arthritis was examined by grading of cellular infiltration and joint destruction as previously described [16].

Immunohistochemistry

Knee joints were removed on Day 3 of AIA in toto and snap-frozen in isopropane/liquid nitrogen. Cryosections of 6 µm were prepared and air-dried. The slides were incubated for 1 h with primary biotinylated mAb against CD3 (C363·29B; Southern Biotechnology Associates, Birmingham, AL, USA), or against CD4 (CT-CD4, Medac, Hamburg, Germany), recognizing a different epitope than GK1·5 (unpublished observation). After rinsing, the slides were incubated for 45 min with streptavidin-conjugated alkaline phosphatase (Dianova, Hamburg, Germany). Neufuchsin was used as substrate. The slides were washed and counterstained with haematoxylin. Positively stained cells were scored semiquantitatively by two observers in a blinded manner (0 = no; 1 = weak; 2 = medium; 3 = strong infiltration of CD3+/CD4+ T-cells).

Preparation of joint extracts

Whole knee joints were removed on Day 3, snap-frozen in liquid N2, and stored at −70°C. The extracts were obtained by grinding the frozen joints under liquid N2 with a mortar and a pestle, followed by addition of 2 ml saline and homogenization with a Dounce homogeniser. After centrifugation for 20 min at 1500 g, the supernatant was aliquoted and frozen at −70°C until further use. Protein concentrations were determined using the BCA-Assay (Pierce, Rockville, IL, USA) and measured cytokine levels (pg) were normalized to per mg total protein.

Isolation and stimulation of cells

Single cell suspensions from whole body lymph nodes and spleens in RPMI 1640, 10% fetal calf serum, 2 mm l-glutamine, 10 mm Hepes (all from Gibco, Karlsruhe, Germany), 100 U/ml penicillin (Jenapharm, Jena, Germany), and 100 µg/ml streptomycin (Grünenthal, Stolberg, Germany) were seeded at 1 × 106 cells per well in 24-well plates and stimulated with PMA (10 ng/ml; Sigma) and ionomycin (500 ng/ml; Sigma). Cell-free supernatants were harvested after 24 h, aliquoted, and stored at − 70°C until analysis.

Cytokine analysis

Concentrations of IL-2, IFN-γ, IL-10, and IL-4 were determined by sandwich ELISA using the following antibody pairs: JES6–1A12 and JES6–5H4 (IL-2, BD Pharmingen, Heidelberg, Germany); R4–6A2 and XMG1·2 (IFN-γ, BD Pharmingen); BVD4–1D11 and BVD6–24G2 (IL-4, BD Pharmingen); JES5–2A5 and JES5–16E3 (IL-10, BD Pharmingen) according to standard procedures.

Determination of serum antibodies

Serum antibodies to mBSA, to collagen type I and II, and to cartilage proteoglycans were measured by ELISA. In brief, ELISA microplates (Greiner, Frickenhausen, Germany) were coated with the antigen (10 µg/ml) overnight [17]. After coating, the wells were washed and blocked with 3% bovine serum albumin in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) for 30 min and washed once more. The sera to be tested were added in appropriate dilutions and the plates incubated for 2 h at room temperature. After washing, the amount of bound antibody was determined by incubation with an antimouse-IgG-peroxidase conjugate (Serva, Heidelberg, Germany) for 1 h, followed by washing and addition of o-phenylenediamine as the substrate. The absorbance was measured at 492 nm in a microplate reader (SLT, Crailsheim, Germany).

Statistical analysis

The nonparametric Mann–Whitney U-test (two-tailed) was applied for analysis of the experimental parameters, with statistically significant differences between the anti-CD4 mAb and control IgG group accepted for P ≤ 0·05.

Analyses were performed using the SPSS 10·0™ program (SPSS Inc.; Chicago, IL, USA).

RESULTS

Clinical effects

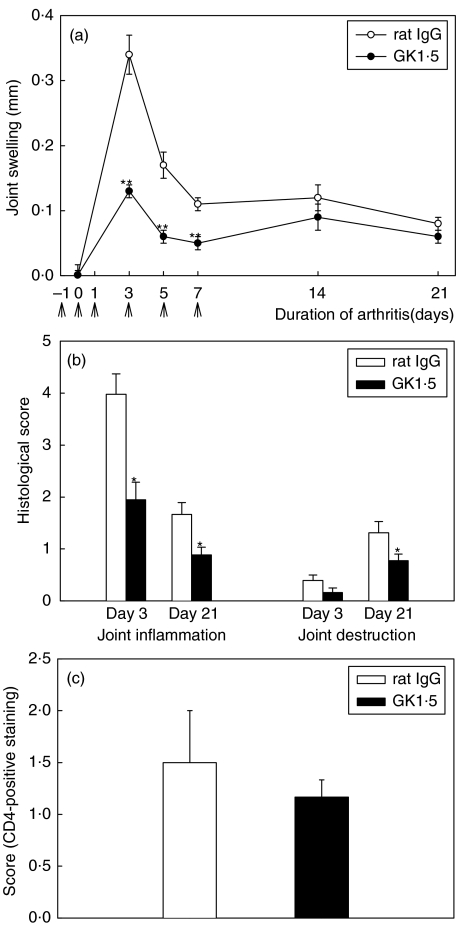

Treatment with the depleting anti-CD4 mAb GK1·5 on Days −1, 0, 1, 3, 5, and 7 led to a highly significant decrease of joint swelling in the acute phase of AIA (Days 3, 5) and in the early chronic phase (Day 7) of AIA compared to the rat IgG-treated control group (Fig. 1a).

Fig. 1.

Swelling, histology, and CD4+ staining of joints with AIA. (a) Time course of joint swelling in AIA after treatment with the anti-CD4 mAb GK1·5 (•) or control rat IgG (○). Arrows indicate the days of treatment (Days −1, 0, 1, 3, 5, and 7). (b) Histological score of joint inflammation and joint destruction in the acute phase (Day 3) and the chronic phase (Day 21) of AIA. (c) Score of CD4-positive staining in the joint of GK1·5-treated (▪) or control (□) animals on Day 3. Results are expressed as means ± SEM of 10 individual animals per group (a,b) or of 5 (rat IgG) and 3 (GK1·5) individual animals per group (c). *P ≤ 0·05, **P ≤ 0·01 in comparison to the rat IgG-treated control group.

The decreased disease activity following GK1·5 therapy was confirmed by analysis of joint histology. Signs of joint inflammation, as defined by hyperplasia of the synovial lining layer and cellular infiltration, were significantly reduced in GK1·5-treated animals both in acute (Day 3) and chronic AIA (Day 21) (Fig. 1b). The joint destruction score, defined as pannus formation as well as erosion of cartilage and bone, became significantly reduced in the chronic phase (Fig. 1b), i.e. the phase with maximal joint destruction [16]. Notably, reduction of clinical signs following anti-CD4 therapy was not accompanied by significant decreases of the densities of CD4+ T-cells or CD3+ T-cells in the synovial membrane on Day 3 (Fig. 1c).

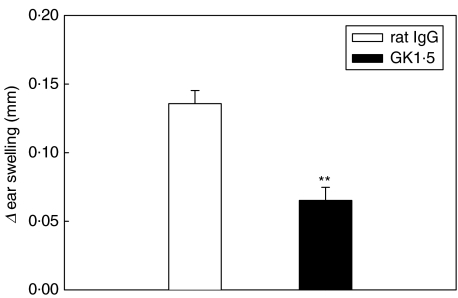

The DTH reaction against the antigen mBSA, used for immunization and induction of AIA, was elicited by intradermal injection of the antigen into the ears of treated or control animals on Day 5 of AIA. After 24 and 48 h, ear swelling was significantly reduced to less than 50% in GK1·5-treated mice compared to controls (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

In vivo T-cell reactivity. Delayed type hypersensitivity to the arthritogen mBSA on Day 5 after induction of AIA. GK1·5-treated animals (▪); control animals (□). Results are expressed as means ± SEM (n = 10 for each group). **P = 0·01 in comparison to rat IgG-treated control group.

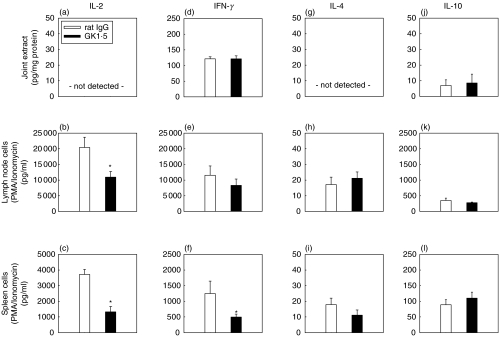

Cytokine levels in joint extracts, in supernatants of spleen and lymph node cells

In order to verify the role of TH1 and TH2 cells in the acute phase of AIA, the production of IL-2, IFN-γ, IL-4, and IL-10 following GK1·5 therapy was investigated in the arthritic joint, as well as in spleen and lymph nodes (LN) on Day 3 of AIA (acute phase).

IL-2/IFN-γ

IL-2 could not be detected in the joint (Fig. 3a). In vivo GK1·5 treatment significantly reduced the IL-2 levels produced by isolated LN and spleen cells following in vitro stimulation with PMA/ionomycin (P ≤ 0·05; Figs 3b,c). For IFN-γ, there was no effect of in vivo anti-CD4 treatment in joint extracts or LN cells (Figs 3d,e). However, there was a significant decrease of the IFN-γ secretion by isolated spleen cells following anti-CD4 therapy (P ≤ 0·05; Fig. 3f).

Fig. 3.

Cytokine levels on Day 3 of AIA. Concentrations of IL-2 (a–c), IFN-γ (d–f), IL-4 (g–i), and IL-10 (j–l) in joint extracts (a,d,g,j), supernatants of PMA/ionomycin stimulated lymph node cells (b,e,k,h), and PMA/ionomycin stimulated spleen cells (c,f,l,i) of (▪) GK1·5-treated or (□) rat IgG-treated mice, as determined by sandwich ELISA. Results are expressed as means ± SEM (n = 6 for each group). *P = 0·05 in comparison to rat IgG-treated control group.

Il-4/IL-10

Secretion of the TH2 cytokines IL-4 and IL-10 in the joint or in stimulated spleen and LN cells remained unchanged by in vivo anti-CD4 therapy (Fig. 3g–l).

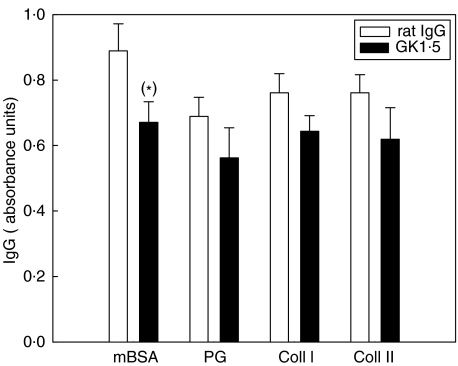

Serum antibody levels

To determine the influence of anti-CD4 mAb therapy on the humoral immune response, serum IgG levels against the arthritogen mBSA and the extracellular matrix components collagen I, collagen II and proteoglycans were measured. There was no influence of anti-CD4 treatment on the humoral response in early AIA (Day 3; data not shown). On Day 21, the specific IgG levels against extracellular matrix components were numerically reduced, and the levels against the arthritogen mBSA moderately reduced (P = 0·07; Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Total IgG levels on Day 21 of AIA. IgG-levels against mBSA, proteoglycan, collagen I, and collagen II from the serum of (▪) GK1·5-treated or (□) rat IgG-treated animals, taken from the chronic phase of arthritis (Day 21). Results are expressed as mean absorbance values ± SEM (n = 10 for each group). *P = 0·07 in comparison to rat IgG-treated control group.

DISCUSSION

Treatment with the anti-CD4 mAb GK1·5 from Day − 1 to Day 7 (i.e. prior to AIA induction, during the acute phase and the early chronic phase of AIA) led to a profound decrease of joint swelling and also significantly reduced histological signs of inflammation. The efficacy of anti-CD4 treatment agrees with a number of reports in collagen-induced arthritis (CIA) [18–20], adjuvant arthritis (AA) [21–24], streptococcal cell wall-induced arthritis (SCW) [25], and in the K/BxN mouse model [26], both upon preventive therapy and treatment in the established phase of arthritis. In AIA, in turn, the efficacy of anti-CD4 mAb treatment is controversial. On one hand treatment was found to suppress clinical and histological signs of inflammation in the flare up reaction [13], but on the other hand there was a lack of influence on clinical and histological signs upon treatment in the acute phase of rat AIA (3, 24, and 48 h post induction) [27].

A surprising finding of this study was that the acute phase of AIA was influenced by anti-CD4 mAb treatment at all and that this effect was even more pronounced than in chronic AIA (Fig. 1). This contradicts the present belief that acute AIA purely depends on immune-complex mechanisms [28,29], as also shown by strong clinical amelioration by anti-CD4 treatment despite a failure of changing antibody levels to mBSA and matrix molecules. It also suggests that the efficacy of anti-CD4 treatment in acute AIA depends primarily, if not exclusively, on the counteraction of pro-inflammatory T-cell functions [10–12,14].

More generally, the present study confirms previous findings on the efficacy of anti-T-cell treatment altogether, for example with anti-TCRα/β mAbs either given preventively and in the early phase or in the early chronic phase of AIA [10]. Furthermore, the present results extend these findings in showing that the subpopulation of CD4+ T-cells is the driving force in joint inflammation and joint destruction during acute AIA.

An influence of anti-CD4 therapy on T-cell reactivity in murine AIA was suggested by a significant decrease of the DTH reaction, as well as a significant decrease of total IL-2 production in whole body LN and IL-2/IFN-γ production in the spleen (although not entirely excluding an effect of CD4+ T-cell depletion). An effect of anti-CD4 treatment on the in vivo T-cell reactivity has also been observed in rat AA [23], however, in that case the DTH to the arthritogen Mycobacterium tuberculosis was significantly increased, possibly due to differences among arthritis models. Decreased production of IL-2/IFN-γ in LN and/or spleen cells following anti-CD4 treatment has also been observed in CIA [19]. Also, a depleting anti-CD4 mAb failed to induce an increase of the TH2-cytokine IL-4 in CIA [19], as also seen in the present study (Fig. 3).

Selective reduction of TH1 cytokines in spleen and LN in conjunction with efficacious anti-CD4 therapy suggests a predominant role of TH1 cells in AIA, in good agreement with the decrease of TH1 cytokines (but an increase of TH2 cytokines), induced by a nondepleting anti-CD4 mAb in CIA [19]. Reports on similar effects of anti-CD4 treatment in transplantation models [30] and even in healthy mice [31] suggest that this facet of anti-CD4 treatment is not restricted to arthritis, but also occurs in other models of pathology and physiology. Interestingly, selective reduction of TH1 cell reactivity following effective anti-CD4 treatment has been also observed in human RA [32].

The borderline effect of anti-CD4 mAb treatment on the antibodies against the arthritogen mBSA in AIA observed in the present study (Fig. 4) is in concordance with significantly reduced antibody responses to the arthritogen in CIA [18,19] and in AA [33]. These findings indicate that antibodies against the arthritogen play a pathogenetic role in a variety of experimental arthritis models, and that even slightly suppressed antibody responses may contribute to the efficacy of anti-CD4 therapy.

In the present study, the anti-CD4 effects were induced by a depleting anti-CD4 mAb. In the past, efficacy of anti-CD4 treatment has been reported using both depleting and nondepleting anti-CD4 mAbs [18–25]. For the treatment of RA, recent clinical studies have focused on the use of nondepleting anti-CD4 mAbs, aimed at influencing the reactivity of CD4+ T-cells rather than removing them completely (reviewed in [3]). These studies indicate that both depleting and nondepleting antibodies may be suitable for the treatment of arthritis, although the underlying therapeutic mechanisms may considerably differ.

Whereas anti-CD4 treatment led to an 88% depletion of CD4+ T cells from the peripheral blood (Day 7), as well as a 50% and 75% depletion of CD4+ T cells from lymph nodes and spleen, respectively (data not shown), there was no influence of the anti-CD4 treatment on the density of CD3+ and CD4+ T-cells in the inflamed synovial membrane. This lack of depletion was observed despite clear clinical efficacy of the treatment. In addition, there was absolutely no influence of the clinically effective anti-CD4 mAb on any of the T-cell cytokines analysed in extracts of arthritic joints (Fig. 3). These findings strongly argue for clinical efficacy of treatment despite sparing of local T-cell functions. The importance of the reduction or coating of CD4+ T-cells in synovial membrane and/or synovial fluid for the efficacy of treatment appears controversial. While some studies report on a positive correlation between the percentage of mAb-coated CD4+ lymphocytes in the synovial fluid and the degree of clinical improvement in RA [34,35], another study describes reduction of the density of CD4+ cells, inflammatory infiltration, and the expression of adhesion molecules despite lack of clinical improvement [36]. However, coating of CD4+ synovial T-cells by therapeutically applied antibody or a shift in the adhesion molecule-dependent migration pattern of CD4+CD45RBhigh/low T-cells (representing naive and memory T-cells, respectively) into the joint can not be totally excluded as an underlying mechanism at present [15,37].

On the other hand, parallel occurrence of local antiarthritic efficacy and reduction of systemic T-cell reactivity (DTH, T-cell cytokines) suggests that systemic counteraction of T-cell functions (e.g. in spleen and LN) strongly contributes to the therapeutic effects. Involvement of systemic sites (spleen, LN, peritoneum, and serum) in the AIA model has recently been demonstrated by the analysis of macrophage-derived cytokines [16]. This notion is also supported by reports on the accumulation of large amounts of anti-CD4 mAb in arthritic joints following i.v. administration [38,39], excluding that a low mAb concentration is a reason for the lack of local effects. A rather marginal importance of local anti-CD4 effects for the efficacy of treatment may also be suggested by the failure of intra-articular application of anti-CD4 mAb to clinically improve human RA despite an overall reduction of the local CD4+ cell infiltration [40].

In conclusion, two novel findings emerge from our study: (1) Systemic, rather than local counteraction of effector T-cell functions (mainly TH1 functions) appears to underlie the beneficial effects of anti-CD4 treatment in the AIA model, previously regarded as a purely monoarticular disease; and (2) T-cell functions, and not only immune complex mechanisms, are a major pathogenetic component in acute AIA, as shown by the efficacy of anti-CD4 therapy accompanied by decreased TH1 levels but unchanged antibody levels.

Acknowledgments

Heidemarie Börner, Cornelia Hüttich, Uta Griechen, Waltraud Kröber, and Renate Stöckigt are gratefully acknowledged for excellent technical assistance, and Dr Ernesta Palombo-Kinne for critical revision of the manuscript. This work was supported by the Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (Grant FKZ 01ZZ9602 to R.B and R.W.K., and 01ZZ0105 to R.W.K) and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Grant Br 1372/5 to R.B., Ki 439/6 to R.W.K).

REFERENCES

- Panayi GS, Lanchbury JS, Kingsley GH. The importance of the T cell in initiating and maintaining the chronic synovitis of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1992;35:729–35. doi: 10.1002/art.1780350702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitzalis C, Kingsley GH, Murphy J, Panayi GS. Abnormal distribution of the helper-inducer and suppressor-inducer T lymphocyte subsets in the rheumatoid joint. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1987;45:252–8. doi: 10.1016/0090-1229(87)90040-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulze-Koops H, Lipsky PE. Anti-CD4 monoclonal antibody therapy in human autoimmune diseases. Curr Dir Autoimmun. 2000;2:24–49. doi: 10.1159/000060506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinne RW, Palombo-Kinne E, Emmrich F. T-cells in the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis: villains or accomplices? Biochim Biophys Acta. 1997;1360:109–41. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4439(96)00079-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox DA. The role of T cells in the immunopathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis: new perspectives. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40:598–609. doi: 10.1002/art.1780400403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crossley MJ, Spowage M, Hunneyball IM. Studies on the effects of pharmacological agents on antigen-induced arthritis in BALB/c mice. Drugs Exp Clin Res. 1987;13:273–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchner E, Bräuer R, Schmidt C, Emmrich F, Kinne RW. Induction of flare-up reactions in rat antigen-induced arthritis. J Autoimmun. 1995;8:61–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Putte LB, Lens JW, van den Berg WB, Kruijsen MW. Exacerbation of antigen-induced arthritis after challenge with intravenous antigen. Immunology. 1983;49:161–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brackertz D, Mitchell GF, Vadas MA, Mackay IR. Studies on antigen-induced arthritis in mice. III. Cell and serum transfer experiments. J Immunol. 1977;118:1645–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshino S, Yoshino J. Suppression of chronic antigen-induced arthritis in rats by a monoclonal antibody against the T cell receptor alpha beta. Cell Immunol. 1992;144:382–91. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(92)90253-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bräuer R, Kette H, Henzgen S, Thoss K. Influence of cyclosporin A on cytokine levels in synovial fluid and serum of rats with antigen-induced arthritis. Agents Actions. 1994;41:96–8. doi: 10.1007/BF01986404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackham A, Griffiths RJ. The effect of FK506 and cyclosporin A on antigen-induced arthritis. Clin Exp Immunol. 1991;86:224–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1991.tb05800.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs MJ, van den Hoek AE, van Lent PL, van de Loo FA, van de Putte LB, van den Berg WB. Role of IL-2 and IL-4 in exacerbations of murine antigen-induced arthritis. Immunology. 1994;83:390–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrow PK, Thoss K, Katenkamp D, Bräuer R. Adoptive transfer of susceptibility to antigen-induced arthritis into severe combined immunodeficient (SCID) mice: role of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Immunol Invest. 1996;25:341–53. doi: 10.3109/08820139609059316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice JC, Bucy RP. Differences in the degree of depletion, rate of recovery, and the preferential elimination of naive CD4+ T cells by anti-CD4 monoclonal antibody (GK1.5) in young and aged mice. J Immunol. 1995;154:6644–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon J, Surber R, Kleinstäuber G, Petrow PK, Henzgen S, Kinne RW, Bräuer R. Systemic macrophage activation in locally-induced experimental arthritis. J Autoimmun. 2001;17:127–36. doi: 10.1006/jaut.2001.0534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bräuer R, Kittlick PD, Thoss K, Henzgen S. Different immunological mechanisms contribute to cartilage destruction in antigen-induced arthritis. Exp Toxicol Pathol. 1994;46:383–8. doi: 10.1016/S0940-2993(11)80121-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranges GE, Sriram S, Cooper SM. Prevention of type II collagen-induced arthritis by in vivo treatment with anti-L3T4. J Exp Med. 1985;162:1105–10. doi: 10.1084/jem.162.3.1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu CQ, Londei M. Induction of Th2 cytokines and control of collagen-induced arthritis by nondepleting anti-CD4. Abstract. J Immunol. 1996;157:2685–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams RO, Mason LJ, Feldmann M, Maini RN. Synergy between anti-CD4 and anti-tumor necrosis factor in the amelioration of established collagen-induced arthritis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:2762–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.7.2762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billingham MEJ, Hicks CA, Carney SL. Monoclonal antibodies and arthritis. Agents Actions. 1990;29:77–87. doi: 10.1007/BF01964727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelegri C, Paz Morante M, Castellote C, Castell M, Franch A. Administration of a nondepleting anti-CD4 monoclonal antibody (W3/25) prevents adjuvant arthritis, even upon rechallenge: parallel administration of a depleting anti-CD8 monoclonal antibody (OX8) does not modify the effect of W3/25. Cell Immunol. 1995;165:177–82. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1995.1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pohlers D, Schmidt-Weber CB, Franch A, Kuhlmann J, Bräuer R, Emmrich F, Kinne RW. Differential clinical efficacy of anti-CD4 monoclonal antibodies in rat adjuvant arthritis is paralleled by differential influence on NF-kappaB binding activity and TNF-alpha secretion of T cells. Arthritis Res. 2002;4:184–9. doi: 10.1186/ar404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelegri C, Morante MP, Castellote C, Franch A, Castell M. Treatment with an anti-CD4 monoclonal antibody strongly ameliorates established rat adjuvant arthritis. Clin Exp Immunol. 1996;103:273–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1996.d01-624.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Broek MF, van de Langerijt LG, van Bruggen MC, Billingham ME, van den Berg WB. Treatment of rats with monoclonal anti-CD4 induces long-term resistance to streptococcal cell wall-induced arthritis. Eur J Immunol. 1992;22:57–61. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830220110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouskoff V, Korganow AS, Duchatelle V, Degott C, Benoist C, Mathis D. Organ-specific disease provoked by systemic autoimmunity. Cell. 1996;87:811–22. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81989-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchner E. 1996. Behandlung der antigen-induzierten Arthritis der Ratte mit Anti-Makrophagenprinzipien und monoklonalen Anti-CD4 Antikörpern. PhD thesis, Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg. [Google Scholar]

- van Lent PL, Nabbe K, Blom AB, Holthuysen AE, Sloetjes A, van de Putte LB, Verbeek S, van den Berg WB. Role of activatory Fc gamma RI and Fc gamma RIII and inhibitory Fc gamma RII in inflammation and cartilage destruction during experimental antigen-induced arthritis. Am J Pathol. 2001;159:2309–20. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)63081-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Lent PL, van Vuuren AJ, Blom AB, Holthuysen AE, van de Putte LB, van de Winkel JG, van den Berg WB. Role of Fc receptor gamma chain in inflammation and cartilage damage during experimental antigen-induced arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:740–52. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200004)43:4<740::AID-ANR4>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegling A, Lehmann M, Riedel H, Platzer C, Brock J, Emmrich F, Volk HD. A nondepleting anti-rat CD4 monoclonal antibody that suppresses T helper 1-like but not T helper 2-like intragraft lymphokine secretion induces long-term survival of renal allografts. Transplantation. 1994;57:464–7. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199402150-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field EH, Rouse TM, Fleming AL, Jamali I, Cowdery JS. Altered IFN-gamma and IL-4 pattern lymphokine secretion in mice partially depleted of CD4 T cells by anti-CD4 monoclonal antibody. J Immunol. 1992;149:1131–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulze-Koops H, Davis LS, Haverty TP, Wacholtz MC, Lipsky PE. Reduction of Th1 cell activity in the peripheral circulation of patients with rheumatoid arthritis after treatment with a non- depleting humanized monoclonal antibody to CD4. J Rheumatol. 1998;25:2065–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelegri C, Castell M, Serra M, Rabanal M, Rodriguez-Palmero M, Castellote C, Franch A. Prevention of adjuvant arthritis by the W3/25 anti-CD4 monoclonal antibody is associated with a decrease of blood CD4 (+) CD45RC (high) T cells. Clin Exp Immunol. 2001;125:470–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2001.01592.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choy EH, Pitzalis C, Cauli A, Bijl JA, Schantz A, Woody J, Kingsley GH, Panayi GS. Percentage of anti-CD4 monoclonal antibody-coated lymphocytes in the rheumatoid joint is associated with clinical improvement. Implications for the development of immunotherapeutic dosing regimens. Arthritis Rheum. 1996;39:52–6. doi: 10.1002/art.1780390107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason U, Aldrich J, Breedveld F, et al. CD4 coating, but not CD4 depletion, is a predictor of efficacy with primatized monoclonal anti-CD4 treatment of active rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2002;29:220–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tak PP, van der Lubbe PA, Cauli A, et al. Reduction of synovial inflammation after anti-CD4 monoclonal antibody treatment in early rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38:1457–65. doi: 10.1002/art.1780381012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hersmann GHW, Kriegsmann J, Simon J, Hüttich C, Bräuer R. Expression of cell adhesion molecules and cytokines in murine antigen-induced arthritis. Cell Adh Comm. 1998;6:69–82. doi: 10.3109/15419069809069761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinne RW, Becker W, Schwab J, Schwarz A, Kalden JR, Emmrich F, Burmester GR, Wolf F. Imaging rheumatoid arthritis joints with technetium-99m labelled specific anti-CD4- and non-specific monoclonal antibodies. Eur J Nucl Med. 1994;21:176–80. doi: 10.1007/BF00175768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinne RW, Becker W, Simon G, et al. Joint uptake and body distribution of a technetium-99m-labeled anti-rat-CD4 monoclonal antibody in rat adjuvant arthritis. J Nucl Med. 1993;34:92–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veale DJ, Reece RJ, Parsons W, et al. Intra-articular primatised anti-CD4: efficacy in resistant rheumatoid knees. A study of combined arthroscopy, magnetic resonance imaging, and histology. Ann Rheum Dis. 1999;58:342–9. doi: 10.1136/ard.58.6.342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]