Abstract

The lymphotoxin-β receptor (LTβR) pathway is critical for maintenance of organized lymphoid structures and is involved in the development of colitis. To investigate the mechanisms by which LTβR activation contributes to the pathology of chronic inflammation we used a soluble LTβR-Ig fusion protein as a competitive inhibitor of LTβR activation in the mouse model of chronic colitis induced by oral administration of dextran sulphate sodium. Strong expression of LTβ which constitutes part of the LTα1β2 ligand complex was detected in colonic tissue of mice with chronic colitis. Treatment with LTβR-Ig significantly attenuated the development and histological manifestations of the chronic inflammation and reduced the production of inflammatory cytokines such as TNF, IL-1β, and IL-6. Moreover, LTβR-Ig treatment significantly down-regulated mucosal addressin cell adhesion molecule-1 (MAdCAM-1) expression, leading to reduced leucocyte rolling and sticking in postcapillary and collecting venules and reduced extravasation into the intestinal mucosa as quantified by in vivo fluorescence microscopy. Thus, LTβR pathway inhibition ameliorates DSS-induced experimental chronic colitis in mice by MAdCAM-1 down-regulation entailing reduced lymphocyte margination and extravasation into the inflamed mucosa. Therefore, a combined treatment with reagents blocking T cell-mediated perpetuation of chronic inflammation such as LTβR-Ig together with direct anti-inflammatory reagents such as TNF inhibitors could constitute a promising treatment strategy for chronic colitis.

Keywords: DSS-induced colitis, LIGHT, LTα1β2, LTβR, MAdCAM-1

Introduction

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is characterized by chronic inflammation of the intestinal tract. Even though its aetiology is still unknown there is increasing evidence that the immune system plays a critical role in the development and perpetuation of ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn's disease (CD). IBD seems an unbalanced version of the normal host defence against luminal antigens or self antigens expressed in the gut mucosa. Recruitment of leucocytes from the gut lumen to mucosal sites is most likely a pivotal step in initiation and perpetuation of disease [1]. Adhesion molecules on the endothelium are recognized by ligands on blood leucocytes mediating a multistep process, involving rolling and tethering of leucocytes, stable adhesion, and transendothelial migration through the vessel wall [2,3]. Leucocyte–endothelial interactions in the gut are critically dependent on mucosal addressin cell adhesion molecule-1 (MAdCAM-1), which is expressed on endothelial cells within the mesenteric lymph nodes and the lamina propria of both the small and the large intestine. MAdCAM-1 expression is strongly increased in animal models of ulcerative colitis, even in the dextran sulphate sodium (DSS)-induced colitis [4,5] and is believed to play a central role in the aetiology of colitis by directing circulating lymphocytes to gut-associated lymphoid and interstitial tissues [6]. Adhesion of α4β7-integrin on a subset of T cells to MAdCAM-1 on cytokine-activated endothelial cells facilitates the extravasation of lymphocytes to inflamed sites in the gut [7].

The relevance of balanced cytokine levels has been established in several colitis models [8]. Both IL-2-deficient and IL-10-deficient mice spontaneously develop colitis. Colitis induced by transfer of CD45RBhi CD4+ T cells into severe combined immunodeficient (SCID) mice was attenuated by neutralization of TNF, IFN-γ, or LTα1β2, demonstrating that these cytokines play a role in the generation of colitis [9,10]. DSS-induced chronic colitis is characterized by ulceration, epithelial damage, mucosal inflammatory infiltrate, and lymphoid hyperplasia [11]. In this model cytokines such as IFNγ, IL-12, and IL-18 have been shown to be critically involved in the pathogenesis [12–15] and the inhibition of MAdCAM-1 ameliorated the disease [5].

The relevance of TNF in experimental colitis as well as in many models of autoimmune disease is well established [9,16–19]. Therapeutic intervention by inhibition of TNF action has been shown to be beneficial in IBD, rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, and ankylosing spondylitis [20–25]. The different members of the TNF receptor family exert distinct biological functions even though there is close molecular relationship of the respective ligands and their receptors. While the TNF system is activated either by TNF or lymphotoxin-α homotrimers (LTα3), the LTβ receptor (LTβR) is activated by membrane bound LTα1β2 heterotrimers or by homologous to Lymphotoxins, exhibits inducible expression, and competes with HSVglycoprotein D for HVEM, a receptor expressed by T lymphocytes (LIGHT) [26,27]. LTβR signalling is believed to participate in the interaction of activated lymphocytes, to which ligand expression is restricted, with nonlymphoid LTβR-bearing cells [28–30]. Furthermore, LTβR signalling is required for differentiation of follicular dendritic cells (FDC) and maintenance of the FDC network [31]. Phenotypic characterization of mice with a genetically disrupted LT pathway revealing a lack of Peyer's patches, of αEβ7-positive peripheral lymphocytes, and low IgA [31–33], together with the experimental evidence of activated T cell involvement in the pathogenesis of IBD [9, 10, 34], suggested a role for the LT system in mucosal immunology. In different colitis models the LT pathway has been shown to be as important as the TNF system for disease development [10,35].

We analysed the role of LTβR activation on lymphocyte extravasation in chronic colitis by treating mice with a LTβR inhibitor consisting of a soluble LTβR-Ig construct. Inhibition of the LT pathway ameliorated chronic DSS-induced colitis and led to significant reduction of MAdCAM-1 expression resulting in significantly less leucocyte rolling and sticking in postcapillary and collecting venules, and reduced extravasation.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Female BALB/c mice were obtained from Charles River (Sulzfeld, Germany). Mice were housed in the animal facilities of the University of Regensburg, handled in accordance with institutional guidelines, and were age, sex and weight (minimum 19 g) matched for experiments.

Induction and treatment of chronic colitis

For induction of chronic colitis mice received four cycles of treatment with DSS. Each cycle consisted of 5% DSS (ICN Biochemicals, Aurora, Ohio, USA) in drinking water for seven days, followed by a 10-day interval with normal drinking water, as described [11].

For therapeutic studies LTβR activation was blocked by treatment with the LTβR-Ig fusion protein. In chronic DSS-induced colitis mice received 100 µg LTβR-Ig i.p. for five days two to three weeks after completion of the four cycles of DSS treatment and were killed on day six. The treatment with LTβR-Ig was restricted to five days in order to avoid complication by mouse anti-human Ig antibodies. Human IgG1 (100 µg in 100 µl PBS) (Sigma Aldrich, Steinheim, Germany) was used as control. Monoclonal antibodies to mouse TNF (V1q) (100 µg in 100 µl PBS) which has been demonstrated to effectively neutralize endogenous TNF in vivo were used as positive therapeutic control treatment [12,17].

Antibodies and Reagents

Expression and purification of the fusion protein LTβR-Ig composed of the extracellular domain of mouse LTβR fused to the Fc domain of human IgG1 has been described recently [36]. Purified human IgG (Sigma Aldrich, Steinheim, Germany) was used as control. The neutralizing monoclonal antibody to mouse TNF (V1q) has been described previously [37]. For MAdCAM-1 staining the rat anti-mouse MAdCAM-1 antibody MECA 367 (Becton Dickinson, Heidelberg, Germany) and for FACS analysis of the α4β7-integin complex a PE-labelled anti-mouse LPAM-1 (α4β7-integin complex) antibody DATK 32 (Beckton Dickinson, Heidelberg, Germany) was used.

Histological scoring and colonic patch scoring

Mice were killed by cervical dislocation, their colons removed and washed with PBS. The distal third of the colon was cut longitudinally, fixed in 10% formalin in PBS overnight, and longitudinal sections of the paraffin-embedded material were made. Three 5 µm sections were cut serially at a distance of 20 µm, the next 3 sections were cut at a distance of 100 µm, and a third set of sections was cut after another 100 µm. The sections were stained with haematoxylin-eosin and 3 sections obtained from each of 3 sites at 100 µm distance were evaluated in a blinded fashion. Mice were scored individually with each score representing the mean of 9 sections.

Histology was scored as follows: epithelium: 0, normal morphology; 1, loss of goblet cells; 2, loss of goblet cells in large areas; 3, loss of crypts; 4, loss of crypts in large areas; infiltration: 0, no infiltrate; 1, infiltration around crypt bases; 2, infiltrate reaching to L. muscularis mucosae; 3, extensive infiltration reaching the L. muscularis mucosae, thickening of the mucosa with abundant oedema; 4, infiltration of the L. submucosa. The colitis score of individual mice represents the sum of the different histological subscores (maximum score = 8).

Colonic patches were scored as follows: 0, no colonic patch; 1, one colonic patch; 2, two colonic patches; 3, three colonic patches; 4, more than three colonic patches, per 1·5 cm colon length.

Measurement of MPO activity

Intestinal myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity was measured as index of neutrophilic granulocyte infiltration. Tissue samples (30 mg) from macroscopically inflamed areas were placed in potassium phosphate buffer (50 mmol/l, pH 6·0) containing 0·5% (w/v) hexadecyltrimethylammonium bromide (1 ml/30 mg tissue), homogenized with an Ultra Turrax (IKA Labortechnik, Staufen, Germany) (3 × 30 s), and subjected to three cycles of freezing and thawing. After centrifugation (20 000 g at 4°C for 20 min) supernatants (10 µl) were transferred into phosphate buffer (pH 6·0) containing 0·17 mg/ml 3,3′-dimethoxy-benzidine and 0·0005% H2O2 and MPO activity was determined by measuring the H2O2–dependent oxidation of 3,3′-dimethoxybenzidine [38].

RNA isolation and RT-PCR

Colons were exteriorized, cleaned, and 1 cm of the distal part of the colon was used for RNA isolation. Total RNA was isolated from the tissue using QIAshredder (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen). RNA was quantified by using Agilent 2100 Bioanalyser according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed as follows: Total RNA (1 µg) from each sample was reverse transcribed in a total volume of 40 µl using the RT-system (Promega, Mannheim, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The reaction mixture was stored at −20°C until further use. The cDNAs (5 µl) were amplified using the following primers: mlTβ 5′primer (5′-CCT GCT GGC TGT GGC AGG AGC TAC-3′) 3′primer (5′-GTA CCA TAA CGA CCC GTA CCC GAT G-3′); mlTα 5′primer (5′-GAA GGG GTA TTG GGA AAA GAG CTG-3′), 3′primer (5′-CTC TAG GGG CCC AGG GAC TCT CTG G-3′); mlIGHT 5′primer (5′-GAG AGT GTG GTA CAG CCT TCA GTG-3′), 3′primer (5′-TGT AAG ATG TGC TGC TGG GTT G-3′); mlTβR 5′primer (5′-GCC GAA GCT TCT GGT GGC CTC TCA GCC CCA G-3′), 3′primer (5′-GCC GGG ATC CGC TCC TGG CTC TGG GGG ATT-3′); β-Actin 5′ primer (5′-TGA CGG GGT CAC CCA CAC TGT-3′), 3′primer (5′-CTA GAA GCA TTT GCG GTG GAC-3′). Annealing temperatures for each primer: mlTβ 60·5°C; mlTα 60°C; mlIGHT 60°C; mlTβR 60°C, β-actin 58·5°C. Samples were kept for 5 min at 95°C and the following 35 cycles were conducted: 95°C for 30 s, annealing temperature for 30 s and 72°C for 30 s. To confirm equal amounts of RNA β-actin cDNA was amplified in each assay. Aliquots of the samples were analysed by electrophoresis on a 1·5% agarose gel and visualized by ethidium bromide staining.

Quantitative polymerase chain reaction

RNA from colon tissue samples was transcribed using the Promega (Mannheim, Germany) Reverse Transcription System following the manufacturer's recommendations. Quantification of cytokines mRNA was performed using a Light Cycler (Roche, Molecular Systems, Mannheim, Germany) according to the manufacturer's recommendations as described [14].

Immunohistochemistry

Intestinal mucosa colonic tissue was immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen after removal and stored at − 80°C. Cryostat sections (5–7 µm thick) were air dried, fixed for 20 min with acetone, and immunohistochemical staining for MAdCAM-1 was performed according to the manufacturer's protocol (Becton Dickinson, Heidelberg, Germany).

FACS analysis

Single cell suspensions from mesenteric lymph nodes from either LTβR-Ig- or control IgG-treated mice were prepared. Lymphocytes were incubated with PE-labelled anti-mouse LPAM-1 (DATK−32, 10 µg/ml) for 30 min on ice, washed twice with PBS (pH 7·2, containing 2% FCS), and fluorescence was analysed using a FACScan flow cytometer.

Microsurgical technique

After premedication with atropine (0·1 mg/kg body weight s.c) animals were anaesthetized with constant flow of oxygen (33%), isoflurane (0·4 vol%) and nitrous oxide and treated as described previously [2]. Mice were placed on a heating pad and the left carotid artery and jugular vein were cannulated for injection of fluorescent dyes for in vivo microscopy and substitution of volume loss.

In vivo microscopy

Part of the mobilized left colon (approximately 1 cm length) was exteriorized on a mechanical stage and covered with a cover slip [2]. Microcirculation of the submucosa was visualized to determine leucocyte endothelium interaction in 10 randomly selected postcapillary and collecting venules. Leucocytes were stained in vivo with acridine orange (0·02%) and classified as rolling, adherent, or nonadherent cells. Each vessel segment was observed for a period of 30 s In order to analyse mucosal microcirculation and lymphocyte extravasation, a longitudinal incision was performed and to visualize the microcirculation of the mucosa fluorescein isothiocyanate-labelled dextran was injected intravenously.

Statistics

Each experiment was performed at least 3 times with similar statistically significant results. For statistical analysis the Student's T-test (cytokine levels) or the Mann–Whitney Rank Sum Test (histological score, colonic patch score, MPO activity, length of colon, in vivo microscopy) was used. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean. Statistically significant when P < 0·05.

Results

Inhibition of LTβR activation ameliorated disease in chronic DSS-induced colitis

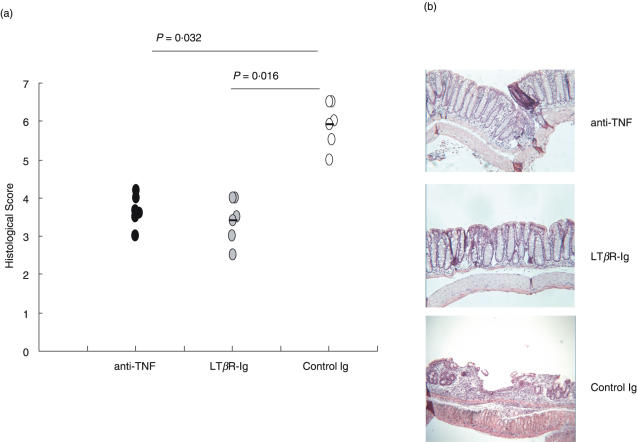

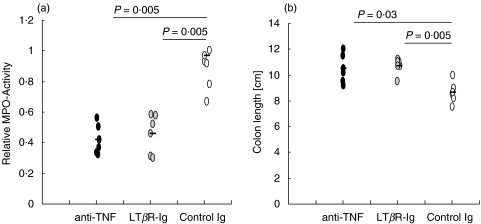

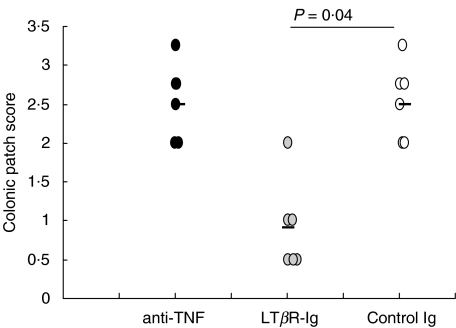

To determine the role of LTβR activation in the development of chronic DSS-induced colitis soluble LTβR-Ig fusion protein was used to block LTα1β2- or LIGHT-mediated functions. Blockade of LTβR signalling in normal adult mice has previously been shown to result in dedifferentiation of the FDC network in the spleen [39]. Three days after a single injection of 100 µg LTβR-Ig i.p. FDC staining in spleens was reduced (data not shown). Treatment of mice with chronic colitis with LTβR-Ig led to a significantly decreased histological score (Fig. 1a) characterized by nearly no loss of crypts and a reduced inflammatory infiltrate compared to the histology of human IgG-treated control mice (Fig. 1b, middle and bottom panel). The mucosal architecture was improved by LTβR blockade and the effect was comparable to that of TNF neutralization (Fig. 1b, top panel). Also, the inflammatory infiltrate of granulocytes (Fig. 2a) and the reduction in colon length (Fig. 2b) were less severe in mice treated with either LTβR-Ig or anti-TNF compared to control mice. Another marker for the severity of colitis is the number and size of colonic patches in the colonic mucosa. Treatment with anti-TNF failed to reduce the colonic patch score, whereas treatment with LTβR-Ig significantly reduced it (Fig. 3).

Fig. 1.

(a) The histological score was determined in mice (n = 6) with chronic colitis after treatment with either LTβR-Ig, anti-TNF or control IgG. Statistical significance was determined using the Mann–Whitney Rank Sum Test. (b) Histology of colon sections from the same mice as in (a).

Fig. 2.

(a) The inflammatory infiltrate of granulocytes in colon tissue sections of mice (n = 6) with chronic colitis treated with either LTβR-Ig, anti-TNF, or control IgG was measured as MPO activity and statistical significance determined using the Mann–Whitney Rank Sum Test. (b) The length of the colons from the same mice as in (a) was measured and the statistic significance of the reduction in length was determined using the Mann–Whitney Rank Sum Test.

Fig. 3.

Lymph node score was determined in mice (n = 6) with chronic colitis after treatment with either LTβR-Ig, anti-TNF, or control IgG. Statistical significance was determined using the Mann–Whitney-Rank Sum Test.

Effect of LTβR-Ig treatment on inflammatory cytokine expression

To determine local changes of key inflammatory cytokines induced by LTβR-Ig treatment mRNAs of IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF were quantified by RT-PCR using mRNA from the distal part of the inflamed colon. LTβR-Ig treatment reduced the amount of mRNA of all three cytokines when compared to control IgG treatment (Table 1). Only 37% of TNF, 10% of IL-1β, and 2% of IL-6 mRNA was detected compared to the control IgG-treated group.

Table 1.

Quantitative RT-PCR for inflammatory cytokines

| Chronic colitis | ||

|---|---|---|

| controlβIgG | LTβR-Ig | |

| IL-1β | 1·26 × 10−4 | 0·13 × 10−4 |

| TNF | 4·50 × 10−4 | 1·70 × 10−4 |

| IL-6 | 61·90 × 10−4 | 1·31 × 10−4 |

Quantitative RT-PCR from colon tissue samples of mice with chronic colitis was performed. mRNA levels of IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF were quantified in mice (n = 5) which had been treated with either LTβR-Ig or control IgG and are given as arbitrary units.

Expression of LTβR and its ligands

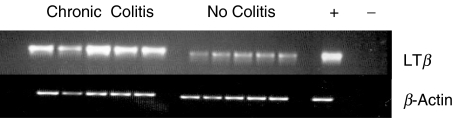

To measure colonic expression of LTβR and of the ligands, LTα1β2 and LIGHT, semiquantitative PCR was performed using mRNA extracted from the distal part of the inflamed colon. Neither transcription of LIGHT, LTα, nor LTβR was significantly modulated compared to healthy control mice (data not shown). In contrast, LTβ mRNA expression was significantly elevated in all mice with chronic colitis compared to mice with acute (data not shown) or no colitis (Fig. 4). FITC-coupled LTβR-Ig bound to CD4+, CD8+, and B220+ cells from the mesenteric lymph nodes only from mice with chronic colitis indicating increased expression of LTα1β2 on lymphocytes of the colonic mucosa during chronic inflammation (data not shown).

Fig. 4.

Semiquantitative RT-PCR for mRNA determination of LTβ, and β-actin was performed from colon tissue of healthy mice or mice with chronic colitis (n = 5).

LTβR-Ig treatment down-regulates MAdCAM-1 expression

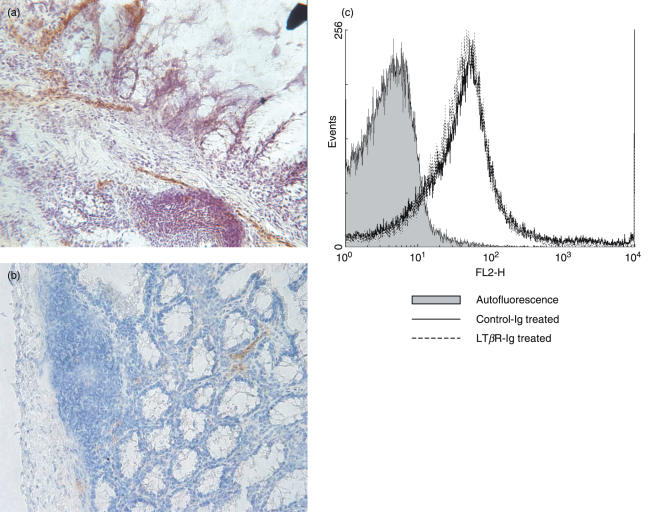

In mice with chronic colitis strong MAdCAM-1 staining was found mainly on the endothelium of venules of the lamina propria, the intestinal mucosa, and on the high endothelial venules (HEV) of colonic patches (Fig. 5a) while only weak MAdCAM-1 staining was observed in the colonic tissue of healthy mice (data not shown). After LTβR-Ig treatment MAdCAM-1 staining was clearly reduced (Fig. 5b).

Fig. 5.

Representative image of the distribution of MAdCAM-1 expression in the inflamed mucosa. Frozen colon sections of either (a) control IgG- or (b) LTβR-Ig-treated mice with chronic colitis were stained for MAdCAM-1. Representative pictures of at least 3 individual stainings (n = 6) are shown. (c) Expression of α4β7-integrin, the ligand for MAdCAM-1, on lymphocytes derived from the mesenteric lymph nodes of either control IgG- or LTβR-Ig-treated mice with chronic colitis. Representative data from at least 3 individual measurements are shown.

The α4β7-integrin is a ligand for MAdCAM-1 and it has been described that LTβR–/– mice have only few αEβ7high-integrin positive lymphocytes [31]. We found no difference in α4β7-integrin staining on lymphocytes of LTβR-Ig-treated mice compared to control IgG-treated mice. Also FACS analysis of α4- and β7-components alone did not show any difference between the two groups (data not shown). Peripheral node addressin (PNAd) which was reported to be regulated by LTβR activation [40] was exclusively found on HEV of the colonic patches during chronic colitis with no difference between control IgG- or LTβR-Ig-treated mice (data not shown). Also, no difference in the amount of L-Selectin or PNAd ligand on lymphocytes from the two groups was detected (data not shown).

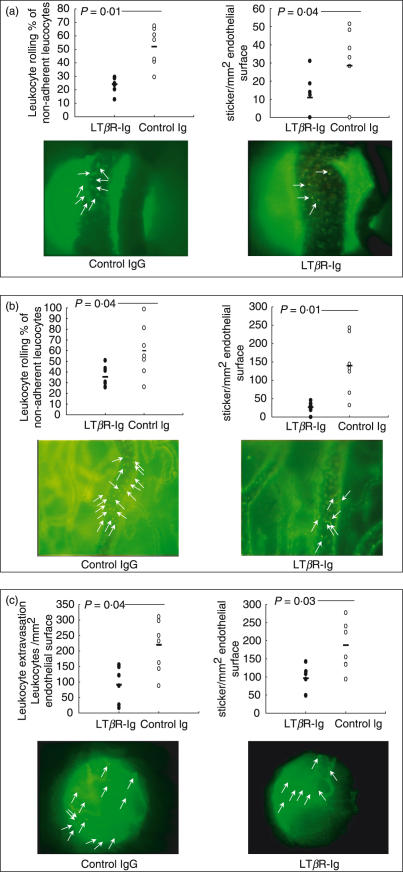

Down-regulated MAdCAM-1 expression after LTβR-Ig treatment causes reduced leucocyte rolling, sticking, and extravasation

In LTβR-Ig-treated mice, the number of rolling and sticking lymphocytes in collecting venules was significantly decreased compared to the control IgG-treated group as visualized by in vivo fluorescence microscopy (Fig. 6a). In submucosal collecting venules significantly fewer leucocytes were seen in close proximity to the endothelial wall. The difference between rolling and sticking leucocytes was made by monitoring the movement of labelled leucocytes over time. Equally, the numbers of leucocytes rolling and sticking in the mucosal postcapillary venules was decreased in LTβR-Ig-treated mice (Fig. 6b). Furthermore, the numbers of leucocytes sticking and extravasated into the colonic mucosa was significantly reduced in mice treated with the LTβR-Ig (Fig. 6c). Taken together, the results from in vivo microscopy strengthen the histological and macroscopic findings of reduced colonic inflammation in mice with chronic colitis after LTβR-Ig treatment by demonstrating reduced leucocyte infiltration into the mucosa and submucosa.

Fig. 6.

In vivo microscopy of mucosal microcirculation in chronic colitis. The numbers (%) of rolling leucocytes or sticking leucocytes (per mm2) as well as pictures are given. Rolling and sticking events of lymphocytes (a) in submucosal collecting venules, (b) in mucosal post capillary venules and (c) sticking events and extravasation of lymphocytes in the mucosa.

Discussion

To unravel the mechanisms by which LTβR blockade results in protective effects in chronic colitis we compared LTβR-Ig treatment to anti-TNF treatment. While TNF initiates the inflammatory cascade and beneficial effects of TNF inhibition may directly result from the anti-inflammatory intervention, the LT/LTβR system appears to lack direct inflammatory effects [41]. LTβR activation rather mediates inflammatory functions by the induction of chemokine secretion [36,42–44]. The relevance of TNF in experimental colitis is well established. Anti-TNF treatment has previously been reported to be beneficial in chronic DSS-induced colitis [9, 16, 17] and in human disease such as IBD [23]. Our data showing that LTβR blockade is equally beneficial as TNF blockade in the model of chronic DSS-induced colitis are in line with the finding in other colitis models that both the TNF and the LT pathway are critically involved in experimental chronic colitis [10,35]. Mice deficient in Peyer's patches and mesenteric lymph nodes develop acute colitis with increased severity [45]. Colonic patch-deficient mice generated by in utero treatment with LTβR-Ig, however, were protected in a hapten-induced colitis model [35]. When we analysed the lymphoid structures in the colonic mucosa of mice with chronic colitis after either anti-TNF or LTβR-Ig treatment we found an important difference between the two groups: whereas anti-TNF-treated mice exhibited the same colonic patch score as control IgG-treated mice, LTβR-Ig treatment reduced the colonic patches in number and size. This might be explained by data showing that LTα1β2 signalling is important for expression of homing chemokines in B and T cell areas of the spleen [46]. Even though expression of B lymphocyte chemoattractant (BLC), EBI-1 ligand chemokine (ELC), and secondary lymphoid tissue chemokine (SLC) seemed dependent on both LTα1β2 and TNF signalling [46] we found a reduction in number and size of colonic patches only after LTβR-Ig treatment but not after TNF neutralization.

The severe colonic inflammation in chronic DSS-induced colitis was accompanied by increased mRNA levels of TNF, IL-1β, IL-6, and LTβ. The mRNA levels of the inflammatory cytokines TNF, IL-1β, and IL-6 were significantly reduced after LTβR-Ig-treatment, indicating less colonic inflammation in such treated mice. The finding that mice with chronic DSS-induced colitis have elevated expression of LTβ, constituting an essential part of the heterotrimeric LTα1β2 molecule, is in line with the observation of increased LTβ staining of CD4+ T cells in biopsies from patients with IBD [47]. Compared to LTβ, the contribution by LIGHT seems less important for the manifestation of chronic colitis as indicated by the strong binding of FITC-labelled LTβR-Ig to CD4+, CD8+ and B220+ cells from mesenteric lymph nodes while no enhanced LIGHT expression was detectable by PCR analysis. Thus, our data do not support the idea of LIGHT as a costimulatory molecule for T cell activation under physiological conditions in vivo as suggested by the finding that LIGHT overexpression led to spontaneous development of intestinal inflammation [48].

Interaction of activated lymphocytes via LTα1β2 with LTβR-bearing cells may provide the molecular mechanism by which the environment alters expression patterns of regulatory factors, e.g. chemokines and adhesion molecules, thus perpetuating chronic inflammation. The observation that LTβR-Ig also attenuated colitis in two T cell transfer models indicates a decisive role of T cell-related functions, including antigen presentation, trafficking, and effector functions for the development of colitis [10]. Based on these data, it can be envisioned that the LT system controls homing mechanisms, especially in mucosa-associated lymphoid tissues. Besides other adhesion molecules induced by inflammatory cytokines and involved in local lymphocyte stimulation and antigen presentation in the intestinal mucosa, MAdCAM-1 seems to play a special role in regulating the influx of lymphocytes in the normal and inflamed gut [1, 2, 4]. Previous reports demonstrated that MAdCAM-1 is critical for the development and severity of colitis in the CD45RBhi T cell transfer model [49] and chronic DSS-induced colitis [1,5]. Neutralizing of α4β7-integrin, the ligand of MAdCAM-1, or of the α4-integrin chain alone, significantly ameliorated colitis [1,50]. Our results are in line with previous findings of reduced MAdCAM-1 staining in spleen and in gut after LTβR-Ig-treatment [51,52]. With intravital fluorescence microscopy we show that the reduced MAdCAM-1 staining after LTβR-Ig treatment coincided with significantly decreased rolling and sticking of lymphocytes to the intestinal epithelium, decreased lymphocyte margination in collecting and post capillary venules, and reduced extravasation of lymphocytes into the inflamed mucosa.

While neutralization of TNF or IFNγ directly reduces the inflammatory reaction, LTβR blockade seems to inhibit the T cell-mediated perpetuation of the chronic inflammation. Thus, the two treatment strategies appear to act independently by interfering with different molecular mechanisms involved in the pathogenicity of chronic DSS-induced colitis. Accordingly, any treatment combination using anti-inflammatory reagents such as TNF inhibitors together with strategies blocking the LT system could result in additive or even synergistic protective effects in chronic colitis. Studies investigating this possibility in different models are currently being performed.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the DFG (SFB 585–02 TPB2).

References

- 1.Van Asche G, Rutgeerts P. Antiadhesion molecule therapy in inflammatory bowel disease. Infl Bowel Dis. 2002;8:291–300. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200207000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Farkas S, Herfarth H, Rössle M, et al. Quantification of mucosal leucocyte endothelial cell interaction by in vivo fluorescence microscopy in experimental colitis in mice. Clin Exp Immunol. 2001;126:250–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2001.01544.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Warnock RA, Campbell JJ, Dorf M, et al. The role of chemokines in the microenvironmental control of T versus B cell arrest in Peyer's patch high endothelial venules. J Exp Med. 2000;191:77–88. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.1.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Connor EM, Eppihimer MJ, Morise Z, et al. Expression of mucosal addressin cell adhesion molecule-1 (MAdCAM-1) in acute and chronic inflammation. J Leukoc Biol. 1999;65:349–55. doi: 10.1002/jlb.65.3.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kato S, Hokari R, Matsuzaki K, et al. Amelioration of murine experimental colitis by inhibition of mucosal addressin cell adhesion molecule-1. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;295:183–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fong S, Jones S, Renz ME, et al. Mucosal addressin cell adhesion molecule-1 (MAdCAM-1). Its binding motif for alpha 4 beta 7 integrin and role in experimental colitis. Immunol Res. 1997;16:299–311. doi: 10.1007/BF02786396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Briskin M, Winsor-Hines D, Shyjan A, et al. Human mucosal addressin cell adhesion molecule-1 is preferentially expressed in intestinal tract and associated lymphoid tissue. Am J Pathol. 1997;151:97–110. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elson CO, Sartor RB, Tennyson GS, et al. Experimental models of inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 1995;109:1344–67. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90599-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Powrie F, Leach MW, Mauze S, et al. Inhibition of Th1 responses prevents inflammatory bowel disease in scid mice reconstituted with CD45RBhi CD4+ T cells. Immunity. 1994;1:553–62. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(94)90045-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mackay F, Browning JL, Lawton P, et al. Both the lymphotoxin and tumor necrosis factor pathways are involved in experimental murine models of colitis. Gastroenterology. 1998;115:1464–75. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70025-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Okayasu I, Hatakeyama S, Yamada M, et al. A novel method in the induction of reliable experimental acute and chronic ulcerative colitis in mice. Gastroenterology. 1990;98:694–702. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(90)90290-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Obermeier F, Kojouharoff G, Hans W, et al. Interferon-gamma (IFN-gamma) - and tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-induced nitric oxide as toxic effector molecule in chronic dextran sulphate sodium (DSS)-induced colitis in mice. Clin Exp Immunol. 1999;116:238–45. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1999.00878.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hans W, Schölmerich J, Gross V, et al. Interleukin-12 induced interferon-gamma increases inflammation in acute dextran sulfate sodium induced colitis in mice. Eur Cytokine Netw. 2000;11:67–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Obermeier F, Dunger N, Deml L, et al. CpG motifs of bacterial DNA exacerbate colitis of dextran sulfate sodium-treated mice. Eur J Immunol. 2002;32:2084–92. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200207)32:7<2084::AID-IMMU2084>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sivakumar PV, Westrich GM, Kanaly S, et al. Interleukin 18 is a primary mediator of the inflammation associated with dextran sulphate sodium induced colitis: blocking interleukin 18 attenuates intestinal damage. Gut. 2002;50:812–20. doi: 10.1136/gut.50.6.812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Neurath MF, Fuss I, Pasparakis M, et al. Predominant pathogenic role of tumor necrosis factor in experimental colitis in mice. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:1743–50. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830270722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kojouharoff G, Hans W, Obermeier F, et al. Neutralization of tumour necrosis factor (TNF) but not of IL-1 reduces inflammation in chronic dextran sulphate sodium-induced colitis in mice. Clin Exp Immunol. 1997;107:353–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1997.291-ce1184.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Flavell RA, Kratz A, Ruddle NH. The contribution of insulitis to diabetes development in tumor necrosis factor transgenic mice. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1996;206:33–50. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-85208-4_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tisch R, McDevitt H. Insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Cell. 85:291–7. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81106-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brandt J, Haibel H, Cornely D, et al. Successful treatment of active ankylosing spondylitis with the anti- tumor necrosis factor alpha monoclonal antibody infliximab. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:1346–52. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200006)43:6<1346::AID-ANR18>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chaudhari U, Romano P, Mulcahy LD, et al. Efficacy and safety of infliximab monotherapy for plaque-type psoriasis: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2001;357:1842–7. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)04954-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goossens PH, Verburg RJ, Breedveld FC. Remission of Behcet's syndrome with tumour necrosis factor alpha blocking therapy. Ann Rheum Dis. 2001;60:637. doi: 10.1136/ard.60.6.637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Present DH, Rutgeerts P, Targan S. Infliximab for the treatment of fistulas in patients with Crohn's disease. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1398–405. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199905063401804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vermeire S, Louis E, Carbonez A, et al. Demographic and clinical parameters influencing the short-term outcome of anti-tumor necrosis factor (Infliximab) treatment in Crohn's disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:2357–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05991.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.St Clair EW. Infliximab treatment for rheumatic disease: clinical and radiological efficacy. Ann Rheum Dis. 2002;61(Suppl. 2):ii67–ii69. doi: 10.1136/ard.61.suppl_2.ii67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ware CF, VanArsdale TL, Crowe PD, et al. The ligands and receptors of the lymphotoxin system. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1995;198:175–218. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-79414-8_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mauri DN, Ebner R, Montgomery RI, et al. LIGHT, a new member of the TNF superfamily, and lymphotoxin alpha are ligands for herpesvirus entry mediator. Immunity. 1998;8:21–30. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80455-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mackay F, Majeau GR, Lawton P, et al. Lymphotoxin but not tumor necrosis factor functions to maintain splenic architecture and humoral responsiveness in adult mice. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:3033–42. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830270830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Browning JL, Sizing ID, Lawton P, et al. Characterization of lymphotoxin-alpha beta complexes on the surface of mouse lymphocytes. J Immunol. 1997;159:3288–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fu YX, Huang G, Wang Y, et al. B lymphocytes induce the formation of follicular dendritic cell clusters in a lymphotoxin alpha-dependent fashion. J Exp Med. 1998;187:1009–18. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.7.1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Futterer A, Mink K, Luz A, et al. The lymphotoxin beta receptor controls organogenesis and affinity maturation in peripheral lymphoid tissues. Immunity. 1998;9:59–70. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80588-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Banks TA, Rouse BT, Kerley MK, et al. Lymphotoxin-alpha-deficient mice. Effects on secondary lymphoid organ development and humoral immune responsiveness. J Immunol. 1995;155:1685–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Koni PA, Sacca R, Lawton P, et al. Distinct roles in lymphoid organogenesis for lymphotoxins alpha and beta revealed in lymphotoxin beta-deficient mice. Immunity. 1997;6:491–500. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80292-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Atreya R, Mudter J, Finotto S, et al. Blockade of interleukin 6 trans signaling suppresses T-cell resistance against apoptosis in chronic intestinal inflammation: evidence in Crohn disease and experimental colitis in vivo. Nat Med. 2000;6:583–8. doi: 10.1038/75068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dohi T, Rennert PD, Fujihashi K, et al. Elimination of colonic patches with lymphotoxin beta receptor-Ig prevents Th2 cell-type colitis. J Immunol. 2001;167:2781–90. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.5.2781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hehlgans T, Stoelcker B, Stopfer P, et al. Lymphotoxin–beta receptor immune interaction promotes tumor growth by inducing angiogenesis. Cancer Res. 2002;62:4034–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Echtenacher B, Falk W, Männel DN, et al. Requirement of endogenous tumor necrosis factor/cachectin for recovery from experimental peritonitis. J Immunol. 1990;145:3762–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Herfarth H, Brand K, Rath HC, et al. Nuclear factor-kappa B activity and intestinal inflammation in dextran sulphate sodium (DSS) -induced colitis in mice is suppressed by gliotoxin. Clin Exp Immunol. 2000;120:59–65. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2000.01184.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Endres R, Alimzhanov MB, Plitz T, et al. Mature follicular dendritic cell networks depend on expression of lymphotoxin beta receptor by radioresistant stromal cells and of lymphotoxin beta and tumor necrosis factor by B cells. J Exp Med. 1999;189:159–68. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.1.159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cuff CA, Sacca R, Ruddle NH. Differential induction of adhesion molecule and chemokine expression by LTalpha and LTalphabeta in inflammation elucidates potential mechanisms of mesenteric and peripheral lymph node development. J Immunol. 1999;162:5965–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hochman PS, Majeau GR, Mackay F, et al. Proinflammatory responses are efficiently induced by homotrimeric but not heterotrimeric lymphotoxin ligands. J Inflammation. 1996;46:220–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Degli-Esposti MA, Davis-Smith T, Din WS, et al. Activation of the lymphotoxin beta receptor by cross-linking induces chemokine production and growth arrest in A375 melanoma cells. J Immunol. 1997;158:1756–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hehlgans T, Männel DN. Recombinant, soluble LIGHT (HVEM ligand) induces increased IL-8 secretion and growth arrest in A375 melanoma cells. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2001;21:333–8. doi: 10.1089/107999001300177529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dejardin E, Droin NM, Delhase M, et al. The lymphotoxin-beta receptor induces different patterns of gene expression via two NF-kappaB pathways. Immunity. 2002;17:525–35. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00423-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Spahn TW, Herbst H, Rennert PD, et al. Induction of Colitis in Mice Deficient of Peyer's Patches and Mesenteric Lymph Nodes Is Associated with Increased Disease Severity and Formation of Colonic Lymphoid Patches. Am J Pathol. 2002;161:2273–82. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64503-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ngo VN, Korner H, Gunn MD, et al. Lymphotoxin α/β and tumor necrosis factor are required for stromal cell expression of homing chemokines in B and T cell areas of the spleen. J Exp Med. 1999;189:403–12. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.2.403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Agyekum S, Church A, Sohail M, et al. Expression of lymphotoxin-beta (LT-beta) in chronic inflammatory conditions. J Pathol. 2003;199:115–21. doi: 10.1002/path.1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang J, Lo JC, Foster A, et al. The regulation of T cell homeostasis and autoimmunity by T cell-derived LIGHT. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:1771–80. doi: 10.1172/JCI13827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Picarella D, Hurlbut P, Rottman J, et al. Monoclonal antibodies specific for beta 7 integrin and mucosal addressin cell adhesion molecule-1 (MAdCAM-1) reduce inflammation in the colon of SCID mice reconstituted with CD45RBhigh CD4+ T cells. J Immunol. 1997;158:2099–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Watanabe C, Miura S, Hokari R, et al. Spatial heterogeneity of TNF-α induced T cell migration to colonic mucosa is mediated by MAdCAM-1 and VCAM-1. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2002;283:G1379–G1387. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00026.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mackay F, Majeau GR, Lawton P, et al. Lymphotoxin but not tumor necrosis factor functions maintain splenic architecture and humoral responsiveness in adult mice. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:2033–42. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830270830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Debard N, Sierro F, Browning J, et al. Effect of Mature lymphocytes and lymphotoxin on the development of the follicle-associated epithelium and M cells in mouse Peyer's patches. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:1173–82. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.22476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]