Abstract

M cells represent an important gateway for the intestinal immune system by delivering luminal antigens through the follicle-associated epithelium to the underlying immune cells. The goal of this study was to characterize this route of antigen uptake during intestinal inflammation by characterizing M cell formation and M cell-associated lymphocytes after indomethacin challenge in rats. We demonstrated increased M cell formation as early as 12 h after a single injection of indomethacin. The elevated M cell counts were determined until day 3 and returned to basal levels after 7 days. Electron microscopic studies revealed an expansion of mononuclear cells inside the M cell pocket that were characterized predominantly as B cells, T cell receptor (TCR)αβ- and CD4-positve T cells, whereas other markers such as CD11b, CD8 and CD25 remained unchanged. In situ hybridization studies showed increased expression of interleukin (IL)-4 by lymphocytes during intestinal inflammation in the Peyer's patch follicle. These studies illuminate the relevance of M cells during intestinal inflammation and suggest that M cells derive from epithelial cells in a certain microenvironment.

Keywords: follicle associated epithelium, indomethacin, ileitis, intestinal M cells, Peyer's patch

INTRODUCTION

The epithelium covering intestinal mucosal surfaces provides an effective barrier to the majority of macromolecules and microorganisms inside the intestinal tract. The effector mechanisms involve the innate and adaptive immune system that requires antigen sampling across the epithelial barrier [1]. This sampling function is carried out in part by specialized cells called M cells (membraneous or microfold), which are found inside the follicle-associated epithelia (FAE) covering the Peyer's patches [2,3]. M cells were first observed by transmission electron microcopy and multiple studies could demonstrate distinct features differentiating them from surrounding epithelial cells, e.g. short irregular microvilli [4,5]. Furthermore, M cells show a deep invagination of the basolateral membrane that contains lymphocytes and phagocytotic leucocytes. Several studies examined the origin of intestinal M cells: initially it was assumed that M cells derive from undifferentiated precursors inside the crypts adjacent to the dome. Further studies that have been performed on the basis of differentiated expression of glycoconjugates on M cell membranes could show that a subpopulation of crypt cells seems to be predetermined as M cells before acquiring the corresponding morphological features [6,7]. However, recent studies could demonstrate that human intestinal epithelial cells may be converted into functional M cells in vitro by interaction with Peyer's patch derived lymphocytes [8,9]. Furthermore, other groups suggested that a differentiation from epithelial cells is more likely than a specific precursor, as a fast increase of M cell numbers at distinct sites of the FAE occurs rapidly after exposure to bacteria [10].

Recently we have shown an increase in M cell numbers during indomethacin induced chronic ileitis in rats [11]. To further evaluate the underlying mechanisms regarding the origin of M cells we examined the kinetics of M cell induction and characterized the associated mononuclear cells in the so-called ‘M cell pocket’. M cells were visualized by their lack of alkaline phosphatase in their apical membrane and by a monoclonal antibody against cytokeratin-8 shown to be M cell-specific in rats [12]. Interacting lymphocytes were characterized by immunohistochemistry and electron microscopy, and induction of cytokine production was determined by in situ hybridization.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and tissue isolation

Female Wistar rats (about 3 months old) were housed in standard wire-mesh bottom cages at constant temperature of 25°C and 12/12 h light/dark cycles. The rats were given water and standard laboratory diet ad libitum with no restriction prior to indomethacin injection.

For tissue isolation animals were killed by cervical dislocation after an overdose of ether. The small intestine was flushed with cold phosphate-buffered saline containing 1 mm Pefabloc (Boehringer, Mannheim, Germany). Peyer's patches were identified by visual inspection; for immunohistochemical studies they were excised and embedded directly in OCT compound (Miles, Elkhart, IN, USA).

Indomethacin-induced ileitis

A total number of 19 rats were examined, including a control group (n = 4). For induction of an acute ileitis rats received one subcutaneous dose of indomethacin (Sigma, 7·5 mg/kg) or vehicle. Tissue was examined after 12, 24, 48 and 72 h and after 1 week. Chronic ileitis was induced by two separate injections of indomethacin (7·5 mg/kg) 24 h apart. The tissue was processed 14 days after the first injection.

Quantification of M cell-associated lymphocytes

Images were taken by using a fluorescence microscope (Nikon Diaphot 200) with a computer-assisted video system (Hamamatsu c4742–56) including the NIH-Image software (NIH Image version 1·67), thereby measuring the surface of the follicle-associated epithelium (FAE). Images were taken at 400×. The created digital image was imported into the NIH-Image software. The length of the FAE was measured by using a 5/17 standard measuring slide (Zeiss) and the absolute number of epithelial cells within the FAE calculated by assuming an average size of a single cell of 7 µm.

M cells were visualized by an alkaline phosphatase staining of the apical membrane, as described earlier [13]. In brief, sections were incubated with Fast-Red (Sigma, 1 mg/ml) in an AP-staining solution (2 mg/ml Naphtol-ASMX-phosphate, 2 ml dimethylformamide, 100 mm Tris-HCL pH 9·5, 100 mm NaCl, 5 mm MgCl2) for 2–3 min. Afterwards sections were washed three times with phosphate buffered saline (PBS).

After AP staining the total number of AP-negative FAE cells was determined and divided by the calculated number of total FAE cells, giving the relative number of M cells within the FAE. Similar analyses were carried out by using the M cell-specific monoclonal antibody anticytokeratin-8, showing equivalent results.

Immunohistochemistry

Cryosections (5 µm) were fixed for 10 min in acetone at −20°C, air-dried and transferred into PBS (pH 7·2). For histological examination sections were stained with haematoxylin and eosin. For immunohistochemistry sections were blocked for 30 min with 10% goat serum in PBS and incubated with the primary antibody in 10% goat serum/PBS for 2 h at room temperature (RT). After three washing steps for 5 min in PBS sections were incubated with a secondary antibody for 1 h at RT. Again the sections were rinsed three times in PBS for 5 min, followed by a FITC-conjugated streptavidin reagent (Dianova, Hamburg, Germany; 5 µg/ml in PBS) for 30 min. After three final washes with PBS for 5 min sections were enclosed in Moviol-gel and evaluated using a Zeiss Axiophat fluorescence microscope. Controls performed under identical conditions without the primary antibody were all negative.

The following monoclonal antibodies were used for characterization of M cell-associated lymphocytes: antirat CD4 (clone W3/25, Diagnostic International,Germany), antirat CD8 (clone Ox8, Diagnostic International, Germany), antirat CD11b (clone WT.5, Pharmingen, San Diego, USA), anti-CD25 (clone OX-39, Research Diagnostics Inc., Flanders, USA), anti-TCRαβ (clone R73, Pharmingen), mouse antirat B cell (clone RLN-9D3, Serotec Ltd, BK), anticytokeratin no. 8 MoAb (clone 4·1.18, Boehringer Mannheim, Germany). A polyclonal biotin-conjugated antimouse Ig antibody (Pharmingen) was used.

Electron microscopy

Tissue specimens were rinsed with PBS, fixed immediately in 2·5% glutaraldehyde in PBS overnight, post-fixed in 1% osmium tetroxide for 2 h, rinsed in PBS and dehydrated through a graded series of ethanol, which was finally replaced with propylene oxide. Afterwards, the tissue was embedded in Epon (Serva, Heidelberg, Germany) and hardened for 48 h at 65°C. After identification of the area of interest on semithin sections stained with toluidine blue Peyer's patches were cut with diamond knives on an ultra-microtome (0·05 µm) and mounted on uncoated mesh grids. The sections were contrasted with 5% uranyl acetate and 0·1% lead citrate and examined with a Philips CM10 electron microscope.

In situ hybridization

A 152 base pairs (bp) fragment corresponding to rat interleukin (IL)-4 was amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) from rat splenic cDNA using an IL-4 forward (5′-ACAA GGAACAC CACGGAGAAC-3′) and reverse (5-GTTCAGACCGCTGA CACCTCTA-3′) primer. The amplified product was inserted into the pGEM-T vector (Promega, Mannheim, Germany) and the orientation of the product confirmed by sequencing. After appropriate linearization sense and antisense orientated FITC labelled probes were synthesized by using the Riboprobe transcription Kit (Promega, Mannheim, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

For in situ hybridization Peyer's patches were removed from the small intestine and fixed for 1 h in 4% paraformaldehyde solution and subsequently incubated in 30% sucrose solution at 4°C overnight followed by embedding into OCT compound. Sections (10 µm) were transferred on SuperFrost plus slides (Fisher Scientific, Schwerte, Germany), air-dried, washed in PBS containing 100 mm glycin and treated for 15 min with 0·3% Triton X-100 (Sigma). After washing with PBS the sections were treated with 5 µg/ml Proteinase K (Sigma) for 30 min at 37°C followed by an incubation in 0·25% acetic anhydride in TEA buffer for 10 min at RT.

For prehybridization the sections were incubated in 200 µl hybridization solution (Sigma) for 1 h at 37°C. After denaturation of the probe (5 µl in 250 µl hybridization solution) sections were hybridized overnight at 55°C in a hybridization oven and washed 2 × 10 min in 2× SSC and 0·5 × SSC at 42°C. After the final wash step sections were mounted in Moviol-gel. Sense probes served as internal controls.

Statistical analysis

M cell numbers after indomethacin injection were analysed by the Mann–Whitney test. P < 0·05 was considered to be statistically significant. Different relative amounts of M cell associated mononuclear cells were compared by the χ2 test.

RESULTS

M cells are rapidly induced after indomethacin injection

Previous studies by our group could demonstrate that M cells are significantly induced during chronic intestinal inflammation [11]. To investigate the kinetics of M cell formation after indomethacin injection we induced an acute intestinal inflammation in rats by a single dose of indomethacin (7·5 mg/kg) and analysed the induction of M cell formation at different time-points (12, 24, 48, 72 h and 7 days). Macroscopical alterations such as hyperaemia, erosions and ulcerations peaked 24 h after injection and lasted maximally 3 days. After 7 days, no gross alterations were visible any more.

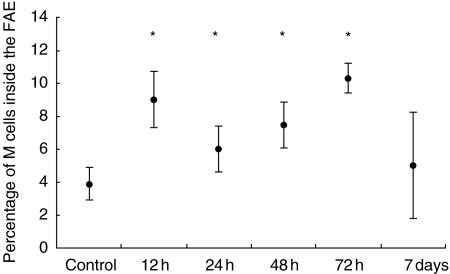

To analyse the induction of M cells, Peyer's patches from multiple rats at each time-point were embedded in OCT, cut into 5 µm sections and stained for alkaline phosphatase. Estimating an average diameter of 7 µm per intestinal epithelial cell we determined the percentage of M cells to regular epithelial cells as 4% corresponding to earlier reports [14]. In the course of an acute intestinal inflammation, a significant increase of M cells inside the FAE could be determined as early as 12 h after indomethacin injection (8·8%). Three days after induction, a significant increase in M cell numbers was still detectable (9·9%), although macroscopic alterations had resolved almost completely. After 1 week the M cell ratio came back to normal values (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Kinetic of M cell induction after indomethacin challenge. The total number of M cells inside the FAE significantly increased as early as 12 h after a single injection of indomethacin. Whereas 72 h after injection still higher levels could be observed, the M cell ratio returned to normal values after 7 days. The data show the results of 10 randomly selected Peyer's patches per rat examined (five sections per PP) from five rats per group (control 4).*P < 0·05 compared to control.

M cell-associated lymphocytes during intestinal inflammation

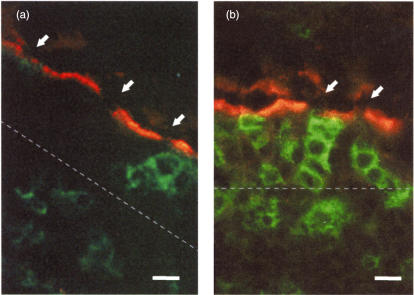

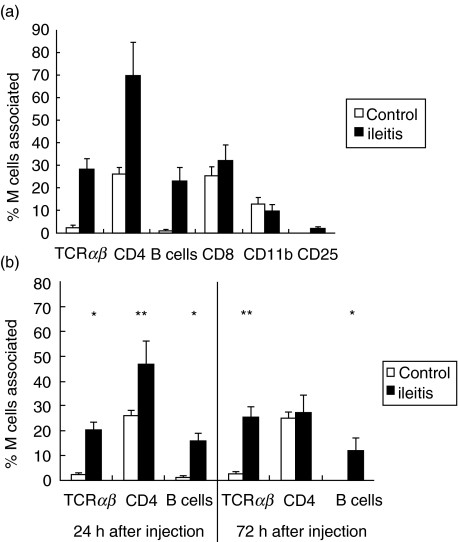

Recent observations demonstrated that M cells might be generated from regular epithelial cells by interaction with Peyer's patch lymphocytes. In addition, M cells are known to be responsible for antigen acquisition from the intestinal lumen. This mechanism is known to be one key event during intestinal inflammation. To investigate the hypothesis that distinct lymphocyte populations are present in the M cell pocket under inflammatory conditions that might be responsible for M cell induction we determined different lymphocyte subpopulations in the chronic and acute model of indomethacin-induced ileitis. Therefore, we performed a double labelling of the M cell area by alkaline phosphatase and antibodies to CD4, CD8, CD11b, TCRαβ and B cells as well as to the activation marker CD25 (Fig. 2). While we could not determine any notable alteration in CD11b or CD8 expressing cells in the chronic model of inflammation 14 days after two injections of indomethacin, there was a significant increase in CD4 and TCRαβ expressing T cells amounting to about 2·5-fold and 5·5-fold, respectively. In addition, we could find a higher number of B cells with the pan B cell antibody RLN-9D3. In contrast, we were not able to detect an elevated expression of CD25 (see Fig. 3a).

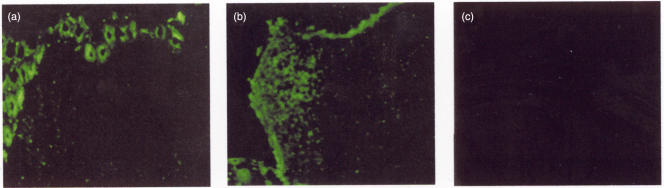

Fig. 2.

Identification of M cells by lack of alkaline phosphatase staining. M cells were identified by the lack of alkaline phosphatase activity (arrows) in their apical membrane; co-staining with markers for different mononuclear subsets such as CD4 in these images (a: control; b: chronic ileitis, bar = 5 µm). The thickness of the epithelium is indicated by a broken line.

Fig. 3.

M cell-associated mononuclear cells during acute and chronic intestinal inflammation. During chronic (a) and acute (b) intestinal inflammation, the amount of M cell-associated B and TCRαβ cells increased significantly, whereas no alterations could be detected for CD8, CD11b and CD25 positve cells. Interestingly, the amount of CD4 positive cells showed only elevated values in the chronic model of intestinal inflammation and 24 h after a single injection, but returned to normal values after 72 h. The data show the mean of eight randomly selected Peyer's patches (three representative sections containing > 300 µm FAE) per rat examined from five rats per group (control 4) and the standard error of the mean (s.e.m.). *P < 0·01; **P < 0·05.

To test if the observed alterations in lymphocyte subpopulation can be observed similarly in the acute model of inflammation we examined the M cell-associated lymphocyte subpopulation at different time-points after indomethacin injection. These results show that parallel to the observation in the chronic model a higher number of M cells associated B, CD4-positive and TCRαβ-positive cells could be observed after 24 h. In contrast to B and TCRαβ-positive cells, the number of CD4-positive cells returned to normal values 72 h after induction of colitis (see Fig. 3b).

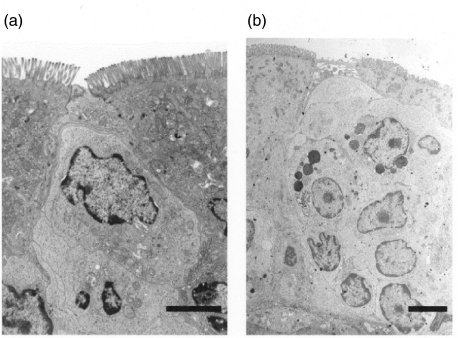

Electron microscopy of M cell pocket during intestinal inflammation

M cells can be identified by electron microscopy due to their unique features with shorter and irregular microvilli compared to neighbouring intestinal epithelial cells as well as by the lymphocytes in the M cell pocket. During intestinal inflammation we could observe a notable increase in the total number of M cell-associated lymphocytes as well as in the total number of M cells (see Fig. 4). Their predominant site of appearance, however, remained on the lateral side of the dome.

Fig. 4.

Transmission electron microscopy of the M cell pocket during intestinal inflammation. After a single injection of indomethacin, the number of M cell associated lymphocytes increased markedly (b) compared to untreated controls (a, bar = 3 µm)

Increased IL-4 mRNA expression by Peyer's patch lymphocytes during intestinal inflammation

Studies in rodents could demonstrate that the PP T cell response to luminal antigens is partially affected by Th2 cells secreting IL-4. Intestinal antigens are at least one key mediator for the induction of intestinal inflammation after indomethacin challenge, and electron microscopy studies revealed an elevated antigen uptake by M cells. Therefore, we performed in situ hybridization analysis for IL-4 expression in inflamed and control intestinal tissue to study if an altered cytokine expression might be involved in elevated M cell formation after indomethacin challenge. Indeed, regular intestinal tissue showed an IL-4 expression by intestinal epithelial cells as well as a small fraction of Peyer's patch lymphocytes inside the follicle and adjacent to the lateral FAE. In contrast, inflamed intestinal tissue showed a significant increase of IL-4 expression by lymphocytes inside the follicle predominantly close to the FAE (see Fig. 5). It might therefore be conceivable that IL-4 expression by Peyer's patch lymphocytes influences M cell conversion from epithelial cells inside the FAE under inflammatory conditions.

Fig. 5.

Increased IL-4 mRNA expression in Peyer's patches. Whereas normal tissue (a) showed IL-4 mRNA expression only inside the epithelia and limited activity inside the follicle, a clear induction inside Peyer's patch lymphocytes could be determined during acute intestinal inflammation (b) with major expression inside the follicle underneath the FAE (c: sense control; bar = 50 µm). IL-4 expression seen within the epithelia was confirmed by RT-PCR on isolated epithelial cells (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

In our study the significant increase of M cells during an acute intestinal inflammation over a short time-course suggests that M cells are involved in the inflammatory process. M cell numbers increased as early as 12 h after indomethacin injection and returned to normal values after 7 days. Furthermore, the observation of distinct lymphocyte populations in the M cell pocket indicates an elevated antigen uptake during acute and chronic intestinal inflammation. Therefore, it might be that M cells are involved in the development of intestinal inflammation and that they are converted rapidly from intestinal epithelial cells inside the FAE by lympho–epithelial interaction under inflammatory conditions.

Although numerous studies have focused on the impact of M cells in various animal models little is known about their role during intestinal inflammation. Recently, we demonstrated that an elevated number of M cells could be observed in the course of a chronic intestinal inflammation in rats where the elevated number of M cells was paralleled with morphological signs of M cell apoptosis [11].

Corresponding to the elevated M cell numbers after indomethacin challenge in rats one group previously described a strong increase of M cells in spondyl-arthropathy associated ileal inflammation in humans [15], whereas other groups reported a loss of M cells from the epithelium of colonic lymphoid follicles in Crohn's disease [16]. These controversial results may reflect different inflammatory conditions or are a result of different techniques used for quantifying M cells, but also demonstrate that to date little is known about the significance of M cells during intestinal inflammation. In our study, we used the lack of AP in the brush border of M cells as a negative marker for M cells which has been shown to be a reliable parameter [13]. Additionally, we correlated the results with a M cell-specific antibody previously described [12] which showed similar results compared to AP-staining (data not shown). We could demonstrate a significant increase in M cell numbers from 4% in non-inflamed follicle associated epithelia to 9·6% over 3 days after the injection, while the level returned to normal values after 7 days. Morphological alterations as hyperemia, wall thickening and ulcer formation detected mainly in the distal jejunum and proximal ileum as described earlier peaked after 24 h and decreased over the following days. After 7 days no gross signs of inflammation were visible any more. However, as the highest M cell number could be detected after 3 days it seems likely that the increased M cell count is a secondary reaction to the inflammatory stimulus rather than a primary effect of indomethacin. Interestingly, we could observe clear differences between the two different models of indomethacin-induced intestinal inflammation: while M cell counts normalized 7 days after one injection of indomethacin we were able to detect elevated numbers 14 days after repeated administration, corresponding to the inflammatory conditions.

Intestinal ulcerations induced by indomethacin in the rat is considered to be a good experimental model for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and recent studies could demonstrate similarities to ileal Crohn's disease focusing on a vascular genesis [17]. However, additional mechanisms like depletion of protective prostaglandins, biliary secretion, genetic susceptibility, food intake and luminal bacteria have been proven to be operative as well [18,19]. As earlier studies could demonstrate M cell induction by bacteria [20] it is conceivable that bacterial invasion of the follicle due to altered barrier function in IBD results in a signal transduction event which stimulates underlying mononuclear cells. These conditions may provide the environment for differentiation of epithelial cells into M cells. However, the main effector mechanisms responsible for M cell formation have not yet been described.

Previous observations in human Peyer's patches suggested that the M cell pocket provides a specialized microenvironment composed of memory T (CD4+ CD45R0+) and memory B (sIgD–CD20+) cells partially expressing the proliferation antigen Ki-67 [21]. More recent observations suggest that cognate B/T cell interaction occurs inside the M cell pocket, thereby promoting diversification of stimulatory mucosal immune responses in an ideally located area to encounter luminal antigens [22]. Our data show a significant elevation of M cell-associated TCRαβ, CD4 and B cells during chronic intestinal inflammation, whereas other cell markers (CD8, CD11b, CD25) were not altered. It is therefore conceivable that the observed increase in B cells and CD4+ T cells reflects an elevated antigen uptake and processing during intestinal inflammation through M cells. Indeed, electron microscopy studies could reveal signs of increased phagocytotic activity inside the M cell pocket. In additon, our recent observations support this view as M cells seem to undergo an apoptotic process during chronic intestinal inflammation, thereby preventing further antigen uptake. It still remains to be elucidated if and how dendritic cells (DC) known to be present within the subepithelial dome area of Peyer's patches [23] are also influencing M cell-mediated antigen processing or M cell formation. Recent observations could demonstrate the expression of the chemokine-receptor CCR6 by myeloid DC [24] that partially express CD4 on their surface, whereas the specific ligand Mip3α is secreted by the FAE. We therefore cannot completely exclude the presence of CD4+ DC in M cell pockets after indomethacin challenge. Interestingly, the deletion of this chemokine receptor does not inhibit the migration of this DC subset [25], but influences M cell formation by reducing CD4+ T cell proliferation (unpublished observations). Further studies have to show whether the M cell-associated CD4 T cells belong to a regulatory T cell population recently described by Jump and Levine within PP, but not in mesenteric lymph node or spleen [26]. Interestingly, this population specifically resides within PP and expresses the activation marker CD69 and low levels of CD45RB, whereas expression of CD25 was similar in all three tissues.

Although multiple studies have examined the ontogenesis of M cells their origin still remains unclear. Until now two major theories have been discussed [27]. Initially, the identification of cells showing distinct M cell features in dome-associated crypts has led to the view that they might constitute a different cell lineage. However, multiple studies could demonstrate that immunological conditions in the FAE are more likely to be responsible for M-cell induction. Savidge et al. could demonstrate that SCID mice lacking mucosal follicles develop follicle-associated epithelia and M cells after reconstitution with Peyer's patch lymphocytes from normal mice [28]. Additionally, Kerneis et al. recently demonstrated an in vitro differentiation of M cell-like cells from Caco-2 cells by co-culturing them with Peyer's patch lymphocytes [8]. It is therefore conceivable that distinct immunological or inflammatory conditions convert enterocytes into M cells, although the major responsible elements are still a controversial issue.

IL-4 represents an important T cell growth factor for the generation of Th2-type and TGF-β-secreting CD4+ T cells within Peyer's patches [29]. Studies by Colgan and coworkers could also show that IL-4 is capable of modulating the function and morphology of intestinal epithelial cell lines [30]. It therefore seems conceivable that IL-4 might represent an important cytokine in the generation of M cells within the FAE. In our study we were able to demonstrate an increased expression of IL-4 within PP after indomethacin challenge by in situ hybridization. However, it seems unlikely that the conversion of M cells from enterocytes is dependent solely on a single cytokine, as regular intestinal epithelial cells are in contact with IL-4-producing T cells as well.

B lymphocytes have been proposed to be effector cells in this process as based on in vivo and in vitro observations: after exposure of mouse FAE with bacteria an expansion of M cells paralleled with a B cell recruitment has been observed [10] and Raji B cells have been described to induce an in vitro conversion of enterocytes into M cells [9]. In our study, we were indeed able to detect elevated numbers of B cells associated with M cells under inflammatory conditions that might be responsible for the observed increased M cell count. However, the parallel-observed expansion of CD4- and TCRαβ-positive T cells as well as the elevated expression of interleukin-4 by PP lymphocytes suggests that a specific microenvironment is more likely to induce M cell differentiation from epithelial cells rather than a specific cell population.

Previous studies have suggested that aphthoid ulcers as early changes in Crohn's disease probably derive from the FAE [31]. Although the exact mechanisms involved in the onset and perpetuation of inflammatory bowel disease have not yet been determined, multiple studies could demonstrate that antigens as well as bacteria play some role in this context [32]. According to our present data, under inflammatory conditions M cells show specific alterations regarding their function as an antigen-sampling system and thus might contribute to the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease.

REFERENCES

- 1.Neutra MR, Pringault E, Kraehenbuhl JP. Antigen sampling across epithelial barriers and induction of mucosal immune responses. Annu Rev Immunol. 1996;14:275–300. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.14.1.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neutra MR. Current concepts in mucosal immunity. V. Role of M cells in transepithelial transport of antigens and pathogens to the mucosal immune system. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:G785–91. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1998.274.5.G785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wolf JL, Bye WA. The membranous epithelial (M) cell and the mucosal immune system. Annu Rev Med. 1984;35:95–112. doi: 10.1146/annurev.me.35.020184.000523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Owen RL, Jones AL. Epithelial cell specialization within human Peyer's patches: an ultrastructural study of intestinal lymphoid follicles. Gastroenterology. 1974;66:189–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Trier JS. Structure and function of intestinal M cells. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1991;20:531–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gebert A, Posselt W. Glycoconjugate expression defines the origin and differentiation pathway of intestinal M-cells. J Histochem Cytochem. 1997;45:1341–50. doi: 10.1177/002215549704501003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Giannasca PJ, Giannasca KT, Falk P, et al. Regional differences in glycoconjugates of intestinal M cells in mice: potential targets for mucosal vaccines. Am J Physiol. 1994;267:G1108–21. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1994.267.6.G1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kerneis S, Bogdanova A, Kraehenbuhl JP, et al. Conversion by Peyer's patch lymphocytes of human enterocytes into M cells that transport bacteria. Science. 1997;277:949–52. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5328.949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kerneis S, Caliot E, Stubbe H, et al. Molecular studies of the intestinal mucosal barrier physiopathology using cocultures of epithelial and immune cells: a technical update. Microbes Infect. 2000;2:1119–24. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(00)01266-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Borghesi C, Taussig MJ, Nicoletti C. Rapid appearance of M cells after microbial challenge is restricted at the periphery of the follicle-associated epithelium of Peyer's patch. Lab Invest. 1999;79:1393–401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kucharzik T, Lugering A, Lugering N, et al. Characterization of M cell development during indomethacin-induced ileitis in rats. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2000;14:247–56. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2000.00688.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rautenberg K, Cichon C, Heyer G, et al. Immunocytochemical characterization of the follicle-associated epithelium of Peyer's patches: anti-cytokeratin 8 antibody (clone 4.1.18) as a molecular marker for rat M cells. Eur J Cell Biol. 1996;71:363–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Owen RL, Bhalla DK. Cytochemical analysis of alkaline phosphatase and esterase activities and of lectin-binding and anionic sites in rat and mouse Peyer's patch M cells. Am J Anat. 1983;168:199–212. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001680207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith MW, Peacock MA. ‘M’ cell distribution in follicle-associated epithelium of mouse Peyer's patch. Am J Anat. 1980;159:167–75. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001590205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cuvelier CA, Quatacker J, Mielants H, et al. M-cells are damaged and increased in number in inflamed human ileal mucosa. Histopathology. 1994;24:417–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1994.tb00550.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fujimura Y, Hosobe M, Kihara T. Ultrastructural study of M cells from colonic lymphoid nodules obtained by colonoscopic biopsy. Dig Dis Sci. 1992;37:1089–98. doi: 10.1007/BF01300292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anthony A, Pounder RE, Dhillon AP, et al. Similarities between ileal Crohn's disease and indomethacin experimental jejunal ulcers in the rat. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2000;14:241–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2000.00694.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Satoh H, Guth PH, Grossman MI. Role of bacteria in gastric ulceration produced by indomethacin in the rat. cytoprotective action of antibiotics. Gastroenterology. 1983;84:483–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kent TH, Cardelli RM, Stamler FW. Small intestinal ulcers and intestinal flora in rats given indomethacin. Am J Pathol. 1969;54:237–49. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Borghesi C, Regoli M, Bertelli E, et al. Modifications of the follicle-associated epithelium by short-term exposure to a non-intestinal bacterium. J Pathol. 1996;180:326–32. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199611)180:3<326::AID-PATH656>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Farstad IN, Halstensen TS, Fausa O, et al. Heterogeneity of M-cell-associated B and T cells in human Peyer's patches. Immunology. 1994;83:457–64. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yamanaka T, Straumfors A, Morton H, et al. M cell pockets of human Peyer's patches are specialized extensions of germinal centers. Eur J Immunol. 2001;31:107–17. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200101)31:1<107::aid-immu107>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Iwasaki A, Kelsall BL. Localization of distinct Peyer's patch dendritic cell subsets and their recruitment by chemokines macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP)-3alpha, MIP-3beta, and secondary lymphoid organ chemokine. J Exp Med. 2000;191:1381–94. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.8.1381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kucharzik T, Hudson JT, III, Waikel RL, et al. CCR6 expression distinguishes mouse myeloid and lymphoid dendritic cell subsets: demonstration using a CCR6 EGFP knock-in mouse. Eur J Immunol. 2002;32:104–12. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200201)32:1<104::AID-IMMU104>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhao X, Sato A, Dela Cruz CS, et al. CCL9 is secreted by the follicle-associated epithelium and recruits dome region Peyer's patch CD11b+ dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2003;171:2797–803. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.6.2797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jump RL, Levine AD. Murine Peyer's patches favor development of an IL-10-secreting, regulatory T cell population. J Immunol. 2002;168:6113–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.12.6113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nicoletti C. Unsolved mysteries of intestinal M cells. Gut. 2000;47:735–9. doi: 10.1136/gut.47.5.735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Savidge TC, Smith MW, James PS. A confocal microscopical analysis of Peyer's patch membranous (M) cell and lymphocyte interactions in the scid mouse. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1995;371A:243–5. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-1941-6_51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Inobe J, Slavin AJ, Komagata Y, et al. IL-4 is a differentiation factor for transforming growth factor-beta secreting Th3 cells and oral administration of IL-4 enhances oral tolerance in experimental allergic encephalomyelitis. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:2780–90. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199809)28:09<2780::AID-IMMU2780>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Colgan SP, Resnick MB, Parkos CA, et al. IL-4 directly modulates function of a model human intestinal epithelium. J Immunol. 1994;153:2122–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fujimura Y, Kamoi R, Iida M. Pathogenesis of aphthoid ulcers in Crohn's disease. correlative findings by magnifying colonoscopy, electron microscopy, and immunohistochemistry. Gut. 1996;38:724–32. doi: 10.1136/gut.38.5.724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fiocchi C. Inflammatory bowel disease: etiology and pathogenesis. Gastroenterology. 1998;115:182–205. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70381-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]