Abstract

The resistance to mousepox is correlated with the production of type I cytokines: interleukin (IL)-2, IL-12, interferon (IFN)-gamma and tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha. We intend to describe the modulation of generalized ectromelia virus (EV) infection with exogenous administration of mrIFN-γ and mrTNF-α separately and in combination using susceptible BALB/c mice. The treatment schemes presented resulted in the localization of the generalized EV infection and its development into non-fatal sloughing of the infected limb. This was accompanied by low virus titres in the treated mice due to control of systemic virus replication and virus clearance. The balance of type I versus type II cytokines was dominated by a type I response in the treated groups. The group treated with the combination of IFN-γ and TNF-α exhibited the best survival with Th1-dominant (IFN-γ and IL-12) cytokine profiles, whereas the TNF-α-treated group of mice was less successful in clearance of virus and demonstrated the lowest survival rate. The successful cytokine treatment schemes in this orthopoxvirus model system may have important implications in the treatment of viral diseases in humans and, in particular, of variola virus infection.

Keywords: cytokines, modulation of generalized infection, mousepox, virus load

INTRODUCTION

The ectromelia virus (EV) is recognized as the aetiological agent of mousepox, a relatively common infection in laboratory mouse colonies around the world. EV, being a natural mouse pathogen, makes mousepox a very useful model of orthopoxvirus (OPV) infection. EV is an example of a species-specific, highly virulent OPV which expresses the major types of immunomodulatory soluble cytokines receptors for interleukin (IL)-1β, tumour necrosis factor (TNF), interferon (IFN)-γ and IFN-α/β, which are highly conserved among different virus isolates [1–5]. Several poxvirus genes have been discovered to encode proteins with sequence similarity to IL-18 binding proteins (IL-18 BPs). The EV IL-18 BP was found to block NF-κB activation and induction of IFN-γ in response to IL-18 [6]. These secreted proteins down-regulate inflammatory responses by sequestering cytokines and preventing their interaction with cellular receptors. The contribution of cytokines in the induction of a protective immune response and recovery from infection with EV has been reported [1,2,7–9]. It is well known that resistance to EV infection and disease correlates with the production of type I cytokines: IL-2, IL-12, IFN-γ and TNF-α. In susceptible BALB/c mice, EV infection predominantly elicits a Th2 immune response with delayed Th1 immunity [7].

The crucial role of IFN-γ in EV in virus clearance at all stages of infection was established and reported in a number of papers [2,8–12]. Treatment with anti IFN-γantibodies in resistant C57BL/6 mice infected with EV transformed a mild, inapparent infection into a fulminant disease similar to that seen in EV-infected highly susceptible mice [8]. IFN-γ is considered a proinflammatory cytokine because it augments TNF activity and induces nitric oxide. Similar to IFN-α and IFN-β, IFN-γ possesses antiviral activity. The antiviral nature of TNF is generally well accepted [13–15]. TNF appears to induce multiple antiviral mechanisms and its synergy with IFN-γ promotes antiviral activities [16–18]. It has been observed in previous studies [15] that TNF receptor-deficient mice that were otherwise resistant to EV were susceptible to lethal infection. In other models the overexpression of TNF during infection with vaccinia virus led to rapid elimination of the virus [13,14].

Thus, on the basis of our knowledge of EV pathogenesis, our intention was to treat mousepox with IFN-γ or TNF-α alone and in combination using susceptible BALB/c mice to study the influence of exogenous administration of these Th1 cytokines on both survival and the clinical picture of the disease by measuring cytokine levels and determining viral loads in blood.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Virus

EV virus, strain K-1 was received from the State Collection of Viruses of the SRC VB ‘Vector’. The source of the virus has been indicated previously [19]. The virus was purified after undergoing one passage through chicken embryos. The virus titre was determined by using a Vero E6 cell monolayer and was calculated to be 7·4 ± 0·4 log10 TCID50/ml, which corresponds to 5·4 ± 0·4 log10 LD50/ml.

Animals

Specific-pathogen-free inbred 4-week-old BALB/c mice (males) were used for the experiment. All animals were obtained from the vivarium of SRC VB ‘Vector’ and were kept at a standard ration.

Preparations

For the treatment of mousepox the following preparations were used: recombinant mouse IFN-γ (rmIFN-γ) (lot CFP03, CFP05, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, USA), the specific activity is established by the manufacturer as 8·43 × 103 IU/µg; and recombinant mouse TNF-α (rmTNF-α) (lot CS082031, R&D Systems), the specific activity is established by the manufacturer as 2·7 × 105 RU/µg.

Preparations rmIFN-γ and rmTNF-α were reconstituted in sterile phosphate buffered saline (PBS) (pH 7·4) before use according to the manufacturer's recommendations.

Experimental design

All mice were infected subcutaneously in the left hind footpad with EV, strain K-1, at a dose of 5 LD50 (in 100 µl of medium RPMI-1640) on day 1. Animals were followed to 21 days post-exposure to observe signs of disease and mortality. All mice were divided into four main groups with different schemes of therapy (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Scheme of experiment

| Group | No. of animals | Group's characteristics | Treatment scheme |

|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | 30 | No treatmentMortality control | – |

| A2 | 40 | No treatmentTaking blood samples | – |

| B1 | 30 | Treatment with rmIFN-γMortality control | Days 4–16 after infection,daily, intraperitoneally,1·7 × 103 IU/mouse |

| B2 | 40 | Treatment with rmIFN-γTaking blood samples | Days 4–16 after infection,daily, intraperitoneally,1·7 × 103 IU/mouse |

| C1 | 30 | Treatment with rmTNFα.Mortality control | Days 4–16 after infection,daily, intraperitoneally,5·4 × 104 RU/mouse |

| C2 | 40 | Treatment with rmTNFα.Taking blood samples | Days 4–16 after infection,daily, intraperitoneally,5·4 × 104 RU/mouse |

| D1 | 30 | Treatment with combination of rmTNFα and rmIFN-γ.Mortality control | Days 4–16 after infection,daily, intraperitoneally,rmIFN-γ 0·85 × 103 IU/mousermTNFα 2·7 × 104 RU/mouse |

| D2 | 40 | Treatment with combination of rmTNFα and rmIFN-γ.Taking blood samples | Days 4–16 after infection,daily, intraperitoneally,rmIFN-γ 0·85 × 103 IU/mousermTNFα 2·7 × 104 RU/mouse |

BALB/c mice were infected with EV, strain K-1, at a dose of 5 LD50.

Animals from group A represented virus control. Animals from groups B, C and D were treated by one of the schemes using different preparations. Preparation doses were chosen empirically. When combined treatments were used, the doses of both preparations were reduced by half.

Mice from groups A1, B1, C1 and D1 were used for mortality control. Animals from groups A2, B2, C2 and D2 were used to obtain serum samples. Blood was taken before infection (day 1) and at selected time-points thereafter until the death of the animals. Blood was taken under methoxyflurane anaesthesia from the orbital sinus. Blood was harvested from three mice at each time-point. After completion of the experiment, the mice were sacrificed using CO2.

The present study was approved by the SRC VB ‘Vector’ Bioethical Committee (IACUC, registered at NIH as A5505-01, 12·26·2001).

Assays

Harvested blood was centrifuged for obtaining serum samples, which were stored at –70°C until the end of the experiment.

Serum levels of cytokines were measured by using enzyme immunoassay kits produced by R&D Systems according to the manufacturer's instructions. Detection limits were as follows: TNF-α, less 5·1 pg/ml; IL-1β, 3·0 pg/ml; IL-6, 3·1 pg/ml; IL-10, 4·0 pg/ml; IFN-γ, less 2 pg/ml; IL-4, less 2 pg/ml; and IL-12, less 4 pg/ml. Ratios of some cytokines were calculated.

EV in the animals’ blood was identified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) as described previously [20]. Total DNA from the blood was isolated using a Qiagen kit (Germany). Primers were as follows: forward 5′-ATACAAAGTCCATGATAAT-3′ (3240–3258 positions in gene) and reverse 5′-ACTCTAGAAGTTTA CACA-3′ (3338–3355 positions in gene). These primers bracketed a 116 base pair (bp) fragment of the MPV ATIB gene, which contains a HindII recognition site generating fragments of 64 bp and 52 bp in size.

To quantify the virus load in blood, EV was titrated on Vero E6 cell monolayers as described earlier [19,21].

On day 21 post-infection, blood of the surviving mice was analysed for anti-EV antibodies (IgG) by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) as described previously[22,23]. Serum samples at a starting dilution of 1 : 10 in PBS-T were titrated through a dilution series in order to obtain the most accurate antibody titre.

Statistical analysis was conducted using Student's t-test or χ2 test. P-values < 0·05 were considered significant. Data represents a mean of ± s.d. Spearman's rank correlation coefficient and a single regression were used to correlate the data of different cytokines and the data of survival/mortality.

RESULTS

Mortality, morbidity, virus titres and serum IgG

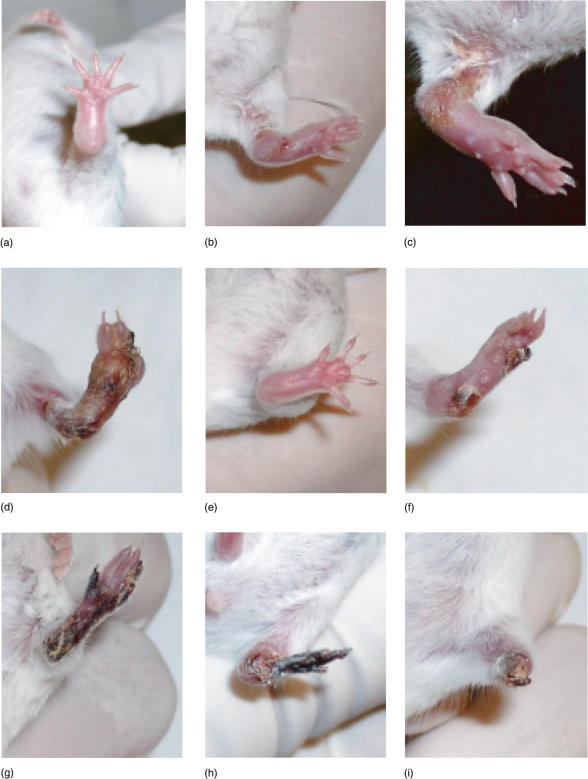

Footpad inoculation of EV, strain K-1, caused the following clinical picture in the sensitive, untreated group A1 of BALB/c mice (see Fig. 1). The manifested swelling of the injected limb in all mice followed reddening at the place of injection from day 4. From day 8, lesions were observed on the swelling limb and from day 10, signs of colliquative necrosis of the limb were noticed. Only a few mice developed initial signs of coagulation necrosis. No sloughing of the infected limb was observed in this group of mice (Fig. 1). Treated animals did not develop extreme swelling, and signs of resolution of inflammation appeared from days 7–8 (Fig. 1). Signs of manifested coagulation necrosis were observed from day 10. Those animals with manifested necrosis and, at the final stage, sloughing of the infected limb, remained active and survived. Mice that did not develop necrosis or sloughing of the infected limbs were less active and died with a similar clinical picture to animals from the control group (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Clinical changes in mice during EV-infection. (a–d) Lethal group of animals on days 5, 8, 10 and 13 (all mice from the control group died) days post-infection, respectively. (e–i) Survived group of animals on days 5, 8, 10, 13 and 20 days post-infection, respectively,

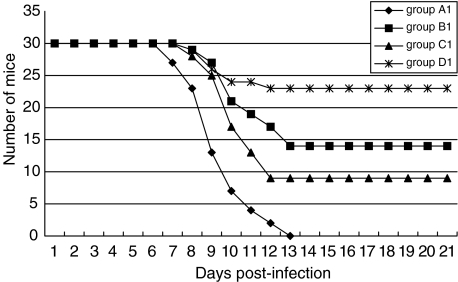

Interestingly, the mean time to death (MTD) of mice from group D1 (the best survival rate) was just equal to the same parameter in the control group. Mortality rates and MTD in all groups of animals are presented in Table 2 and Fig. 2. We estimated that days 7–13 were the ‘critical period’, as all deaths were observed within those days. There was a statistical difference in the survival rates between the control group and the treated groups (P = 0·0331; 0·0068; 0·0002) of mice. Mice that received both IFN-γ and TNF-α (group D1) showed statistically higher survival rates in comparison with all other treated groups of animals (P < 0·02).

Table 2.

Mortality rate, mean time to death in different groups of BALB/c mice infected with EV, strain K-1, at a dose of 5 LD50 and treated by different schemes

| Group | No. of mce | Mortality rate (%) | MTD (day) |

|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | 30 | 100 | 9·34 ± 0·32 |

| B1 | 30 | 53·3 | 10·52 ± 0·46* |

| C1 | 30 | 70 | 10·10 ± 0·40* |

| D1 | 30 | 23·3 | 9·34 ± 0·88 |

For schemes of rmTNF-α and rmIFN-γ treatment see Table 1.

Statistically different from the control (P = 0·0086; 0·0421 correspondingly).

Fig. 2.

Dynamic of mortality of BALB/c mice infected with EV, strain K-1, at a dose of 5 LD50 and treated by different schemes. Group A1, control; group B1, rmIFN-γ treatment; group C1, rmTNF-α treatment; group D1, combination treatment. For schemes of rmTNF-α and rmIFN-γ treatment see Table 1.

The development of mousepox in BALB/c mice was accompanied by EV replication in all groups (Table 3). Blood titres of virus increased progressively to the day of death in the control group A2 (maximum = 6·8). The highest virus titres in the blood of treated mice were statistically lower (P < 0·01) in comparison to the maximum level in the control animals. From day 7 virus load decreased in all treated mice, and by day 21 it was cleared from the blood of all surviving mice.

Table 3.

EV titre (log10 TCID50/ml) in blood of BALB/c mice infected with EV, strain K-1, at a dose of 5 LD50 and treated by different schemes

| Day post-infection | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | 7 | 9 | 11 | 21 | |

| A2 | 5·2 ± 0·2 | 6·2 ± 0·4 | 6·5 ± 0·4 | 6·8 ± 0·4 | – |

| B2 | 5·1 ± 0·2 | 5·6 ± 0·2* | 5·2 ± 0·2 | 4·6 ± 0·2** | 0 |

| C2 | 5·0 ± 0·1 | 5·8 ± 0·2* | 5·6 ± 0·2 | 5·2 ± 0·2 | 0 |

| D2 | 5·2 ± 0·1 | 5·6 ± 0·2* | 5·2 ± 0·2 | 4·7 ± 0·2** | 0 |

Statistically significant difference with the maximum in the control A2 group (P < 0·01).

Statistically significant difference with group C2 on day 11 (P < 0·05). Mice were treated by different schemes of rmTNF-αand rmIFN-γ (see Table 1).

On day 21 post-infection, the mean anti-EV IgG titres in survived mice were as follows: group B2, 1 : 160, group C2, 1 : 120 and group D2, 1 : 50. Thus, the lowest IgG titres were recorded in mice from the D2 group with the best survival rate.

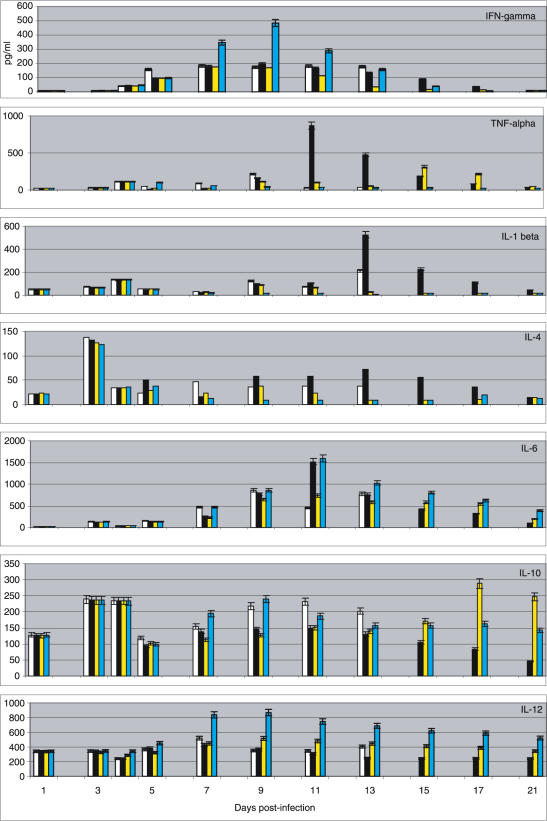

Cytokines (Fig. 3)

Fig. 3.

Serum levels of IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-4, IL-6, IL-10 and IL-12 in BALB/c mice infected with EV, strain K-1, at a dose of 5 LD50 and treated by different schemes. x-axis: days; y-axis: concentrations in pg/ml. Day 1: EV virus inoculation. Day 4: beginning of treatment by different schemes of rmTNF-α and rmIFN-γ(see Table 1). □, control group A2;j, IFN-γ-treated group B2;  , TNF-α-treated group C2;

, TNF-α-treated group C2;  , IFN-γ : TNF-α-treated group D2.

, IFN-γ : TNF-α-treated group D2.

The most prominent increase of IFN-γ was in mice from group D2 (P < 0·05 in comparison to all other groups) during the ‘critical period’. The maximum levels of IFN-γ in the IFN-γ-only treated group (B2) were very similar to the control group, and in group C2 they were even lower than in the control.

The most impressive increase of TNF-α was observed on day 11 (869·9 pg/ml) in the IFN-γ-treated group of mice (P < 0·001 in comparison with all other groups). In the TNF-α-treated group, TNF-α concentrations were not high until day 15. In the combination-treated group D, levels of TNF-α did not show a significant increase and were the lowest except on day 5.

The highest level of IL-1β (525·8 pg/ml) was recorded in group B2 mice (P < 0·002 in comparison with all other groups); this group also had the highest TNF-α concentrations. In general, the lowest levels of IL-1β were observed in the best-surviving D2 group mice. TNF-α and IL-1β showed a high correlation with the survival rate, r = −0·74 (P = 0·0245); r = −0·84 (P = 0·0146), respectively, and with mortality, r = 0·79 (P = 0·0017); r = 0·81 (P = 0·0013), respectively, in the IFN-γ-treated group.

An abrupt and steep increase of IL-4 was detected on day 3 after the challenge, but was followed by a sudden decrease on day 4 in all groups. In general, the highest concentrations of IL-4 were observed in group B2 (P < 0·02) except on day 7; the lowest levels (lower than on day 1) were detected in group D2 (P < 0·05 in comparison with all other groups). A correlation with the survival rate, r = −0·82 (P = 0·0435) and with the mortality < r = 0·82 (P = 0·0274) within ‘critical days’ in the IFN-γ-treated mice was not observed in all other groups.

Similarly, impressive peaks of IL-6 levels were seen on day 11 in the best-survival groups B2 and D2 (P < 0·008). The IL-6 level remained highest in group D2 mice; however, in group B2 the peak was significantly reduced 2 days later.

Interestingly, the highest levels of IL-10 were found in mice from the control group and in the best-survival D2 group of mice within the ‘critical period’. However, the maximum level of IL-10 significantly decreased in group D2 from day 9 to day 13. An unexpected increase of IL-10 was found in group C2 after the ‘critical’ period.

IL-12 levels were dominant in group D2 throughout the entire period of observation (P < 0·05–0·002). IL-12 levels in group B2 were the lowest among all treated groups. There was a strong negative correlation with IL-10 in the control group (r = −0·99; P = 0·0012), a moderately negative correlation in the TNF-α-treated group, a weak positive correlation in the IFN-γ-treated group and a strong positive correlation (r = 0·9; P = 0·0383) in the combination-treated group. IL-12 showed a moderate correlation with IFN-γ in the control and TNF-α-treated groups, and a strong positive correlation in the IFN-γ and the combination-treated groups (r = 0·95–0·80; P < 0·01). The strong negative correlation between IL-4 and IL-12 in the IFN-γ-treated group (r = − 0·91; P < 0·01) was not observed in the other treated groups.

Several empirical indices were calculated, such as the ratios of IFN-γ to IL-10 [24], IL-12 to IL-10 [25], IFN-γ to IL-4 [26] and IL-12 to IL-4 (data not shown). Within the ‘critical period’, IL-12/IL-10 (P < 0·02) and IFN-γ/IL-10 (P < 0·03) were higher in all treated groups in comparison to the control; IL-12/IL-4 (P < 0·001) and IFN-γ/IL-4 (P < 0·002) were significantly higher in the combination-treated group in comparison with all other groups.

DISCUSSION

EV is a natural mouse pathogen, which causes a generalized infection. The mousepox model has been used extensively to study pathogenesis of not only OPV, but also of generalized viral infections and viral immunology [7,27–30]. Orthopoxviruses express a wide variety of proteins that are non-essential for virus replication in culture, but do help the virus to evade the host response to infection [1]. We have attempted to ‘treat’ generalized infection with the systemic (i.p.) administration of IFN-γ or TNF-α alone or in combination with the purpose of saturating the EV-expressed cytokine receptors, such as vTNFR and vIFN-γR, and by this way to achieve a reduction of the host's cytokines sequestering.

In susceptible strains of mice, mousepox is an acute generalized infection producing high viral titres in the liver and spleen with resultant necrosis and high mortality. In contrast, infection of mousepox-resistant mice is usually subclinical, with lower levels of viral replication in the visceral organs and development of non-fatal local (injected foot site) lesions. The cytokine treatments reported here resulted in localization of the EV infection followed by the non-fatal sloughing of the infected limb. Dead mice from the treated groups, as well as all mice from the control group, failed to localize infection and had no limb sloughing. In our experiments, all treated groups of mice had statistically lower viral loads in peripheral blood in comparison to the control. Thus, the localization of EV infection was accompanied with low virus titres, and the obvious ‘treatment’ effect in our study was the influence on virus replication and virus clearance. These points indicate that treated mice were able to control systemic virus replication. Based on data from previous studies [15], TNF clearly plays a determining role in resistance to EV, but it is less critical than IFN-γ. In our study, the TNF-α-treated group of mice was less successful in clearance of virus than the IFN-γ-treated and IFN-γ : TNF-α-treated mice. The successful suppression of cytokines production by the Th2 CD4+ T cells is known to abolish the T-dependent IgG response [28]. The non-specific effectors, including IFNs and TNF, limit the spread of the virus early during infection before the generation of antigen-specific immune responses such as antibodies and CTL. The best-surviving IFN-γ : TNF-α-treated group of mice showed the lowest specific IgG titre. In our study, the dominating production of Th1 cytokines (IFN-γ, IL-12) in this group of mice could be considered a relative suppression of Th2 cytokine production.

IFN-γ synergizes with TNF [16–18], dramatically enhancing its antiviral effects. In our study, the most successful recovery process was noted in the group treated with a combination of IFN-γ and TNF-α. Reducing the doses of IFN-γ and TNF-α by half, but administering them in combination, led to similar (in comparison with the IFN-γ-treated group) or lower (in comparison with the TNF-α-treated group) virus loads in peripheral blood of these group mice.

The i.p.-administered IFN-γ and TNF-α might bind/neutralize the corresponding viral receptors, bind with the host cellular receptors producing complexes, or both. This is one of possible explanations for why we did not observe an increase in the corresponding cytokine concentrations in treatment groups B and D. Moreover, high exogenous doses of IFN-γ and TNF-α in these groups could reciprocally suppress the host endogenous production of the corresponding cytokines.

A strong cellular immune response is associated with the production of a number of cytokines, particularly INFs, IL-2 and IL-12, and is thought to be of paramount importance in virus clearance and the recovery process [28]. In our study, in addition to low EV virus titres in mice blood, animals from the most successful IFN-γ : TNF-α-treated group also produced the highest concentrations of IL-12 and IFN-γ. Previous results [20] have demonstrated that endogenous type I and type II cytokine responses cross-regulate immunity to acute VV infection with IL-12 and IL-10 as the dominant factors for resistance and susceptibility, respectively. The strong antagonism between IL-10 and IL-12 in the control group, which was manifested by the strong negative correlation coefficient, led to the suppression of a protective inflammatory immune response and to the development of generalized fatal EV infection. The strong positive correlation in the best combination-treated group of mice may mean that the growth of IL-12 was not suppressed by the IL-10 concentrations and moreover, IL-12 concentrations were dominant, which was confirmed by the ratio of IL-12/IL-10. A strong positive correlation of IL-10 with the mortality rate was observed only in the control and TNF-α-treated groups.

IL-12 is critical to the induction of IFN-γ production from T and natural killer (NK) cells and initiates the development of cell-mediated immunity by promoting the differentiation of Th1 cells from naive T cells [21,31]. The correlation between IFN-γ and IL-12 from moderate in the control and TNF-α-treated groups became a strong positive in the IFN-γ and the combination-treated groups.

The data mentioned above demonstrate that the balance of type I versus type II cytokines was changed to a dominant type I response in the treated groups with the different level of advantage. Thus, the balance between the activities of EV IFN/TNF inhibitors and the ability of the host to produce inflammatory immune response was improved.

An excess of IL-4 has been shown to be deleterious for the host as it down-regulates IL-12 and IFN-γ production and inhibits the production of TNF-α by macrophages [21,32–34]. The unexpected high concentrations of IL-4 in the IFN-γ-treated group resulted in a strong negative correlation between IL-4 and IL-12 and the lowest ratios of IFN-γ/IL-4, IL-12/IL-4 within the ‘critical period’. There was also a strong negative correlation of IL-4 with the survival rate, as well as a strong positive correlation with the mortality within those ‘critical days’, which was not observed in all other groups. Nevertheless, these unfavourable signs seem to not be extremely important in comparison to the lowest blood virus titres, as IFN-γ-treated mice had better survival than TNF-α-treated mice with a higher blood virus titre. However, these unfavourable signs did not permit IFN-γ-treated mice to obtain the same survival rate as the combination-treated group.

It is known that endogenous IL-6 plays a crucial anti-inflammatory role by controlling the levels of TNF-α and IL-1β and IL-6 activities may be viewed as an attempt to bring the host back to homeostasis [35]. In our opinion, IL-6 might play such a role in the best-survival IFN-γ- and IFN-γ: TNF-α-treated groups.

The high concentrations of IL-1β and TNF-α in the IFN-γ-treated group, indicative of a dominant Th1 cellular response, were detrimental to the animals. This was confirmed by a strong negative correlation of IL-1β and TNF-α with the survival rate and a strong positive correlation with the mortality rate in that group.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated possible treatment modalities for generalized EV infection in mice. The most successful treatment was combination low doses of rmTNF-α and rmIFN-γ administered systemically (i.p.). In this group, low peripheral blood virus titres accompanied by high levels of IFN-γ and IL-12 led to the best survival rate.

The pathogenesis of mousepox has been characterized extensively in the past; it is clearly a preferred model for studying the role of immunomodulatory factors in OPV infections [1]. In the present study, we have made an attempt to regulate the host cell immune answer to generate an appropriate type of immune response against a particular pathogen. In order to develop the most accurate and successful scheme of treatment, we are planning to expand on the experiments reported here. We did not measure the dynamic of IL-18. However, it is of special interest to compare IL-18 levels in groups with the different treatment schemes taking into account the importance of IL-18 BP in the virus life cycle. It will also be interesting to treat EV infection with IL-18 and study its effect on the disease pathogenesis. Successful cytokine treatment schemes in this model system may have important implications in the treatment of orthopoxvirus infection in humans.

Acknowledgments

We thank Alexandr Agafonov for assistance with the viral work. This work was funded by Antibody Systems Inc. (Hurst, Texas, USA). We are grateful to ASI staff for excellent technical support.

REFERENCES

- 1.Smith VP, Alcami A. Expression of secreted cytokine and chemokine inhibitors by ectromelia virus. J Virol. 2000;74:8460–71. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.18.8460-8471.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith VP, Alcami A. Inhibition of interferons by ectromelia virus. J Virol. 2002;76:1124–34. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.3.1124-1134.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Loparev VN, Parsons JM, Knight JC, et al. A third distinct tumor necrosis factor receptor of orthopoxviruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:3786–91. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.7.3786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mossman K, Upton C, Buller RM, McFadden G. Species specificity of ectromelia virus and vaccinia virus interferon-gamma binding proteins. Virology. 1995;208:762–9. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alcami A, Smith GL. A soluble receptor for interleukin-1β encoded by vaccinia virus: a novel mechanism of virus modulation of the host response to infection. Cell. 1992;71:624–33. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90274-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith VP, Bryant NA, Alcami A. Ectromelia, vaccinia and cowpox viruses encode secreted interleukin-18-binding protein. J General Virol. 2000;81:1223–30. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-81-5-1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mahalingam S, Karupiah G, Takeda K, et al. Enhanced resistance in STAT6-deficient mice to infection with ectromelia virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:6812–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.111151098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karupiah G, Fredrickson TN, Holmes KL, et al. Importance of interferons in recovery from mousepox. J Virol. 1993;67:4214–26. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.7.4214-4226.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jackson RJ, Ramsay AJ, Christensen CD, et al. Expression of mouse interleukin-4 by a recombinant ectromelia virus suppresses cytolytic lymphocyte responses and overcomes genetic resistance to mousepox. J Virol. 2001;75:1205–10. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.3.1205-1210.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karupiah G, Xie QW, Buller RM, et al. Inhibition of viral replication by interferon-gamma-induced nitric oxide synthase. Science. 1993;261:1445–8. doi: 10.1126/science.7690156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Imanishi J, Matsubara M, Won CJ, et al. Combined protective effects on interferon and interferon induction on herpes simplex and ectromelia virus infections in mice. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1981;19:922–4. doi: 10.1128/aac.19.5.922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Niemialtowski MG, Spohr de Faundez I, Gierynska M, et al. The inflammatory and immune response to mousepox (infectious ectromelia) virus. Acta Virol. 1994;38:299–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sambhi SK, Kohonen-Corish MRJ, Ramshaw IA. Local production of tumor necrosis factor encoded by recombinant vaccinia virus is effective in controlling viral replication in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:4025–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.9.4025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lidbury BA, Ramshay IA, Sambhi SK. The role for host-immune factors in the in vivo antiviral effects of tumor necrosis factor. Cytokine. 1995;7:157–64. doi: 10.1006/cyto.1995.1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ruby J, Bluethmann H, Perschon J. Antiviral activity of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) is mediated via p55 and p75 TNF receptors. J Exp Med. 1997;186:1591–6. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.9.1591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wong GH, Goeddel DV. Tumor necrosis factor α and β inhibit virus replication and synergise with interferons. Nature (Lond) 1986;323:819–22. doi: 10.1038/323819a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lucin P, Jonjic S, Messerle M, et al. Late phase inhibition of murine cytomegalovirus replication by synergistic action of interferon-gamma and tumour necrosis factor. J Gen Virol. 1994;75:101–10. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-75-1-101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Suk K, Chang I, Kim Y-H, et al. Interferon γ (IFN-γ) and tumor necrosis factor α synergism in ME-180 cervical cancer cell apoptosis and necrosis. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:13153–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007646200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kochneva GV, Urmanov IH, Ryabchikova EI, et al. Fine mechanisms of ectromelia virus thymidine kinase-negative mutants avirulence. Virus Res. 1994;34:49–61. doi: 10.1016/0168-1702(94)90118-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Neubauer H, Pfeffer Meyer H. Specific detection of mousepox virus by polymerase chain reaction. Lab Anim. 1997;31:201–5. doi: 10.1258/002367797780596275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van den Broek M, Bachmann MF, Köhler G, et al. IL-4 and IL-10 antagonize IL-12-mediated protection against acute vaccinia virus infection with a limited role of IFN-γ and nitric oxide synthetase 2. J Immunnol. 2000;164:371–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.1.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Collins MJ, Peters RL, Parker JC. Serological detection of ectromelia virus antibody. Lab Anim Sci. 1981;31:595–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Buller RML, Bhatt PN, Wallace GD. Evaluation of an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for the detection of ectromelia (mousepox) antibody. J Clin Microbiol. 1983;18:1220–5. doi: 10.1128/jcm.18.5.1220-1225.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sobue S, Nomura T, Ishikawa T, Ito S, et al. Th1/Th2 cytokine profiles and their relationship to clinical features in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection. J Gastroenterol. 2001;36:544–51. doi: 10.1007/s005350170057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Feng WH, Tompinks MB, Xu JS, et al. Analysis of constitutive cytokine expression by pigs infected in-utero with porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2003;94:35–45. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2427(03)00059-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Granchi D, Savarino L, Ciapetti G, et al. Immunological changes in patients with primary osteoarthritis of the hip after total joint replacement. J Bone Surg Br. 2003;85:758–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fenner F, Wiltek R, Dumbell KR. The orthopoxviruses. San Diego, CA: Academic Press Inc.; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Karupiah G, Buller RML, Rooijen NV, et al. Different roles CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes and macrophage subsets in the control of a generalized virus infection. J Virol. 1996;70:8301–9. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.12.8301-8309.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Buller RML, Palumbo CJ. Poxvirus pathogenesis. Microbiol Rev. 1991;55:80–120. doi: 10.1128/mr.55.1.80-122.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fenner F, Buller RML. Mousepox. In: Nathanson N, editor. Viral pathogenesis. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven; 1997. pp. 535–53. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Trincheri G. Interleukin-12: a proinflammatory cytokine with immunoregulatory functions that bridge innate resistance and antigen-specific adaptive immunity. Annu Rev Immunol. 1995;13:251–76. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.13.040195.001343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peleman R, Wu J, Fargeas C, Delespesse G. Recombinant interleukin-4 suppresses the production of interferon gamma by human mononuclear cells. J Exp Med. 1989;170:1751–6. doi: 10.1084/jem.170.5.1751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tanaka T, Hu-Li J, Seder RA, et al. Interleukin 4 suppresses interleukin 2 and interferon γ production by naive T cells stimulated by accessory cell-dependent receptor engagement. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:5914–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.13.5914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hart PH, Vitti GF, Burgess DR, et al. Potential anti-inflammatory effects of interleukin 4: suppression of human monocyte tumor necrosis factor alpha, interleukin 1, and prostaglandin E2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:3803–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.10.3803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xing Z, Gauldie J, Cox G, et al. IL-6 is an anti-inflammatory cytokine required for controlling local or systemic acute inflammatory responses. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:311–20. doi: 10.1172/JCI1368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]