Abstract

Regulation of the immune response directed against Leishmania is critical for the establishment of effective control of the disease. It is likely that some types of immune responses directed against Leishmania can lead to more severe clinical forms of leishmaniasis causing a poor control of the pathogen and/or pathology, while others lead to resolution of the infection with little pathology as in cutaneous leishmaniasis. To gain a better understanding of the possible role that subpopulations of T cells, and their associated cytokines have on disease progression and/or protective immune responses to L. braziliensis infection, a detailed study of the frequency of activated and memory T cells, as well as antigen specific, cytokine producing T cells was carried out. Following the determination of cytokine producing mononuclear cell populations in response to total Leishmania antigen (SLA), and to the recombinant antigen LACK, correlation analysis were performed between specific cytokine producing populations to identify models for cellular mechanisms of immunoregulation in human cutaneous leishmaniasis. These studies have shown: (1) a positive correlation between ex vivo CD45RO frequencies and antigen specific cytokine (IFN-gamma or IL-10) producing cells; (2) a negative correlation between ex vivo CD69 expression and the frequency of IFN-gamma producing cells; (3) a positive correlation amongst SLA specific, IFN-gamma or TNF-alpha and IL-10 producing lymphocytes with one another; and (4) a higher frequency of IL-10 producing, parasite specific (anti-SLA or anti-LACK), lymphocytes are correlated with a lower frequency of TNF-alpha producing monocytes, demonstrating an antigen specific delivery of IL-10 inducing negative regulation of monocyte activity.

Keywords: leishmaniasis, cytokines, T cells, immunoregulation, T helper cells

INTRODUCTION

Leishmaniasis is caused by infection with the protozoan parasite from the gender Leishmania and affects millions of individuals worldwide causing serious morbidity and mortality. The exacerbation, as well as control of infection, depends on several host and parasite related factors [1,2].

In the murine model of L. major infection, the predominant CD4+ T cell subpopulation resulting from infection greatly influences the outcome of disease [3,4]. Interleukin-12 (IL-12) produced by macrophages and dendritics cells and interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) produced by natural killer cells (NK), and previously activated T cells, promote the development of Th1 cells, whereas IL-4 induces the development of Th2 cells. The Th1 subpopulation, important for induction of leishmaniasis resistance, produce IFN-γ and tumour necrosis factor -alpha (TNF-α) which play an important role in cellular immune responses against intracellular pathogens by activating macrophages for intracellular killing of pathogens [5]. On the other hand, Th2 cells produce IL-4, IL-5, IL-10, and IL-13, and are associated with leishmaniasis susceptibility in L. major infection murine models [6–8]. In human, IL-10, a key macrophage deactivating cytokine, is not restricted to Th2 cells and can be produced by several types of T helper populations [9].

In L. braziliensis induced cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) soluble Leishmania antigen (SLA) induces a higher frequency of IFN-γ and TNF-α producing lymphocytes (CD4+, double negative lymphocytes, and CD8+ T cells) than does the Leishmania homolog of receptors for activated kinase C (LACK) antigen [10]. LACK is a conserved protein in Leishmania species that makes up only about 0·03% of the total protein present in Leishmania[11]. Neither SLA nor LACK induce detectable frequencies of cells producing interleukin-4 (IL-4) or IL-5 in patients with CL [10]. Previously we have shown that CD4+ T cells are major sources of IFN-γ producing cells upon SLA stimulation in vitro. Moreover, high levels of IFN-γ and TNF-α producing cells have been identified after cure of the disease [12,13]. These findings suggest that the resolution of the cutaneous clinical form is associated with immune response comprised of Th1 CD4+ T lymphocytes.

In addition to mounting an effective Th1 response against leishmaniasis, the immunoregulation of the subsequent inflammatory response is important and necessary for maintaining host tissue integrity. Recently, exacerbated Th1 type responses have been associated with the mucosal clinical form of leishmaniasis [14]. On the other hand, it was recently shown that patients infected with Leishmania but that do not develop the disease have a balanced Th1 and Th2 immune response to SLA, producing higher IL-5 levels than CL patients [15]. To determine cellular mechanisms involved in the immune response directed against L. braziliensis that lead to the subsequent resolution of infection, a thorough characterization of cell populations ex vivo and following stimulation with specific antigens was performed in a group of individuals with CL, that later resolved their primary lesions. Based on these data, we show a series of correlation analysis at the individual level proposing a model of cellular mechanisms involved in the induction and possible control of the immune response directed against Leishmania in humans.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

The peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) analysed in this study were obtained from nine individuals from the endemic area for L. braziliensis, Corte de Pedra, in the state of Bahia, Brazil. All individuals participated in the study through informed consent and received treatment independent of their enrolment in our study. Diagnosis of CL was based on clinical findings, positive parasitological exams, and a positive skin test (DTH) for Leishmania antigens. The DTH test was read on the forearm 48 h after the injection of 25 µg of total Leishmania antigen in 0·1 ml of distilled water as approved by the Brazilian Ministry of Health. A test is considered positive when an area of induration of >5 mm in diameter is achieved. The mean age for the patients was 21·67 years ± 4·85 (range 17–32 years). All presented with ulcerated lesions that had been detected between 15 days and three months prior to blood collection. None of the individuals had been previously treated for leishmaniasis and reported no prior infections with Leishmania. In this endemic area approximately 90% of the patients cure the first cutaneous lesions following the administration of appropriate treatment. The blood was drawn immediately before any treatment was initiated.

Synthesis and purification of the antigens

The recombinant antigen LACK from Leishmania major was produced in our laboratory. The plasmid pET3-A containing the cDNA for the protein LACK was obtained in collaboration with Dr Richard Locksley (UCSF, San Francisco, CA, USA). The histidine tagged recombinant protein was expressed in bacteria B21(DE3)pLysS (NOVAGEN). It was then purified over an affinity column of nickel (HisTrap-Pharmacia). The purified fractions were confirmed using silver stained SDS-PAGE gels. LACK from L. major has no amino acid changes in the predicted protein sequence compared to L. braziliensis. The Soluble Leishmania Antigen (SLA) of L. braziliensis was provided by the Leishmaniasis Laboratory (ICB/UFMG/Brazil, Dr W. Mayrink) and is a freeze/thawed antigen preparation. Briefly, L. braziliensis promastigotes (MHOM/BR/81/HJ9) were washed and adjusted to 108 promastigotes/ml in PBS followed by repeated freeze/thaw cycles and a final ultrasonication. All antigens were titrated using PBMC from patients infected with L. braziliensis.

In vitro cultures

All cultures were carried out using RPMI 1640 (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO, USA) supplemented with 5% heat inactivated human serum AB Rh + (Sigma), antibiotics (200 U/ml penicillin) (Sigma), and 1 mm l-glutamine.

Ex vivo staining to determine lymphocyte profile

PBMC from CL patients were obtained by separating whole blood over Ficoll and washing three times with medium. 2 × 105 PBMC were incubated with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)- or phycoerythrin (PE)-labelled antibody solutions for 20 min at 4°C. After staining, preparations were washed with 0·1% sodium azide PBS, fixed with 200 µl of 2% formaldehyde in PBS and kept at 4°C until data were acquired using a fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACSCallibur, Becton & Dickinson, San José, CA, USA). The antibodies used for the staining were immunoglobulin FITC and PE controls, anti-CD4-PE, anti-CD8-FITC and -PE, anti-CD69-FITC (PharMigen, San Diego, CA, USA), anti-CD45-RO-FITC, anti-CD14-FITC (Dako, Colorado, USA).

Single-cell cytoplasmic cytokine staining

PBMC were analysed for their intracellular cytokine expression pattern as described below and by Botrell et al. [10]. Briefly, 2·5 × 106 PBMC were cultured in 24-well plates in 1 ml cultures for 20 h with either medium alone (RPMI 1640 supplemented with 5% heat inactivated human serum AB Rh +, 200 U/ml penicillin and 1 mm l-glutamine), and the addition of; LACK (at 20 µg/ml final concentration), SLA (at 10 µg/ml final concentration), or a positive control of anti-CD3/CD28 (anti-CD3 of 2 µg/ml and anti-CD28 of 1 µg/ml). During the last 4 h of culture, Brefeldin A (1 µg/ml) (PharMigen) was added to the cultures. The cells were then harvested, washed and stained for surface markers, and fixed using 2% formaldehyde (Sigma). The fixed cells were then permeabilized and stained, using anti-cytokine monoclonal antibodies (Pharmingen) directly conjugated with either FITC (IFN-γ (clone B27)) or PE (TNF-α (clone Mab11) and IL-10 (clone JES3–19F1). FITC and PE-labelled immunoglobulin control antibodies and a control of unstimulated PBMC were included in all experiments. Preparations were then analysed selecting the lymphocyte, blast or monocyte populations. In all cases, 30 000 gated events were acquired for later analysis due to the low frequency of positive events being analysed.

Analysis of FACS data

Leucocytes were analysed for their intracellular cytokine expression patterns and frequencies and for surface markers in a number of ways using the program Cell Quest (Becton & Dickinson, San José, CA, USA). The frequency of positive cells was analysed in three regions for each staining; lymphocyte gate, large lymphocyte blast gate and monocyte/macrophage gate. Limits for the quadrant markers were always set based on negative populations and isotype controls. This approach of analysis allows for the frequency of populations to be determined in subregions of mononuclear cells, making use of known positioning of mononuclear cells based on size and granularity profiles. Correlations were considered significant when a P-value equal to or less than 0·05 was returned using the software, JMP from SAS.

RESULTS

Ex vivo frequency of CD45RO expressing T cells is correlated with a higher frequency of cytokine producing cells

In order to test the degree to which ex vivo indicators of early activation (CD69 expression) and of previous antigenic exposure (expression of CD45RO) are correlated with antigen specific cytokine production, correlation analysis were performed between the frequency of CD4+ T cells expressing these molecules and the frequency of CD4+ T cells producing either TNF-α, IL-10 or IFN-γ in response to SLA stimulation. Only comparisons that demonstrated statistially significant negative or positive correlations are represented. Thus, the omition of a given correlation indicates that a given pair showed no associations between one another.

The ex vivo frequency of CD4+CD69+ T cells within the CD4+ T cell population was negatively correlated with the frequency of IFN-γ producing SLA specific cells (Fig. 1a). In contrast, there was a direct correlation between the frequency of CD4+CD45RO+ T cells, and the frequency of both IFN-γ (Fig. 1b) and IL-10 (Fig. 1c) producing SLA specific T cells. This correlation was striking for both cytokine producing populations, while the overall frequency (as determined by taking the mean of the cytokine positive cells for all individuals in the figure) of CD4+ T cells committed to IFN-γ production (2·39%) was much higher than the frequency of IL-10 producing cells (0·14%). No correlation was seen between these ex vivo parameters and the frequency of TNF-α producing cells (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

CD45RO expression is correlated with cytokine producing lymphocytes. Correlation between CD69 or CD45RO expression analysed ex vivo and CD4+ T lymphocytes producing IFN-γ stimulated with SLA for 20 h as described in Materials and Methods. (a) Demonstrates the correlation between CD69 and IFN-γ expression (n = 9). (b) Correlation between CD45RO expression analysed ex vivo and production of IFN-γ (n = 9) or (c) IL-10 by SLA specific CD4+ T lymphocytes (n = 8). The graphs show fit lines with 95% confidence curves.

Thus, at the individual level, higher frequencies of memory/experienced CD4+ T cells predicted higher commitment to SLA specific cytokine producing cells, both of the inflammatory (IFN-γ) and of the regulatory nature (IL-10).

A positive correlation is seen amongst SLA specific cytokine producing lymphocytes

While a high frequency of SLA specific cytokine producing cells are seen in human CL, the degree to which counteracting (IFN-γ or TNF-α and IL-10) and/or cooperative (IFN-γ and TNF-α) cytokine producing cells are coregulated is unknown. Thus, correlations were performed between the frequencies of cells producing these important immunoregulatory cytokines and one another following a 20 h stimulation with SLA and analysis by flow cytometry. This early time point was chosen to reveal the cytokine profile of lymphocytes that were previously activated and differentiated in vivo in response to L. braziliensis infection. Analysis was performed using different regions, as described in Materials and Methods.

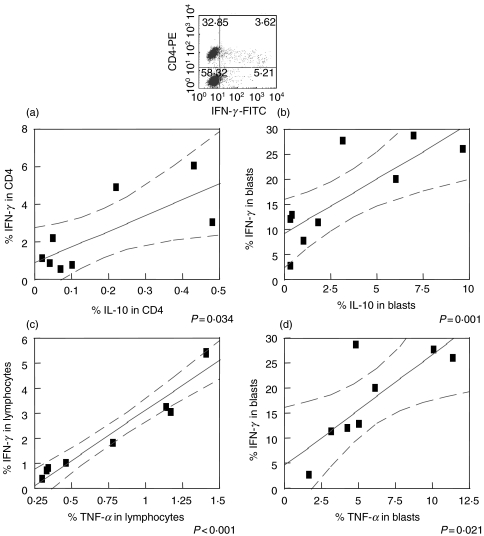

A positive correlation was seen between the commitment by SLA specific CD4+ T cells to produce IFN-γ or IL-10 (Fig. 2a). The same was seen for overall frequency of blast lymphocytes producing IL-10 or IFN-γ following SLA stimulation (Fig. 2b). Furthermore, a positive correlation was also seen between the frequency of total lymphocytes producing TNF-α or IFN-γ (Fig. 2c) as well as for blast lymphocytes (Fig. 2d). Importantly, while there exists a positive correlation between the frequency of cytokine producing cells in each individual tested, the overall average frequency (as determined by taking the mean of the cytokine positive cells for all individuals) of IFN-γ producing cells (2·40%) was higher than that seen for either TNF-α (0·82%) or IL-10 (0·20%) producing cells. No correlations were seen between cells maintained in media alone. In contrast, as a positive control the production of cytokines by cells stimulated by anti-CD3/CD28 were also analysed. The same correlations were observed with the polyclonally stimulated cells (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

Positive correlation between SLA specific cytokine producing lymphocytes. The frequency of cytokine producing lymphocytes was determined following SLA stimulation of PBMC from cutaneous leishmaniasis patients for 20 h. IL-10 and IFN-γ production (a) by CD4+ T lymphocytes and (b) by blast lymphocytes. Total TNF-α and IFN-γ production (c) by lymphocytes and (d) by blast lymphocytes. The graphs show fit lines with 95% confidence curves. (n = 8)

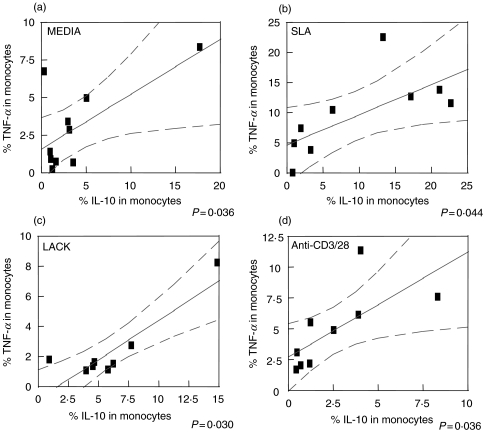

A positive correlation between the frequency of IL-10 and TNF-α producing monocytes was seen independent of the stimuli used

The regulation of cytokine producing monocyte populations has implications for understanding the self-regulation of inflammatory responses, initiated following monocyte activation by antigen specific T cells and/or the microenvironment present in infected individuals. Thus, the frequency of monocytes producing TNF-α or IL-10 was determined and compared between one another for each individual.

The analysis demonstrated a positive correlation between the frequency of IL-10 and TNF-α producing monocytes independent of the stimuli used. Whether cultured in media alone (Fig. 3a), with SLA (Fig. 3b), LACK (Fig. 3c), or anti-CD3/28 (Fig. 3d), all samples presented with a positive correlation between the frequency of TNF-α producing and IL-10 producing monocytes. However, the strongest correlations were seen in antigen stimulated cultures. This effect of antigenic simulation on the cytokine production is seen dramatically when comparing the overall average frequency of TNF-α producing monocytes from cultures with media alone (2·54%) to that seen in cultures stimulated with SLA (8·08%).

Fig. 3.

Positive correlation between TNF-α and IL-10 producing monocytes. Percentage of cytokine-producing monocytes was determined following the indicated culture conditions of PBMC from cutaneous leishmaniasis patients for 20 h. (a) TNF-α and IL-10 production without stimuli (n = 10); (b) stimulated with SLA (n = 9); (c) stimulated with LACK (n = 8), and (d) stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28 (n = 9). The graphs show fit lines with 95% confidence curves.

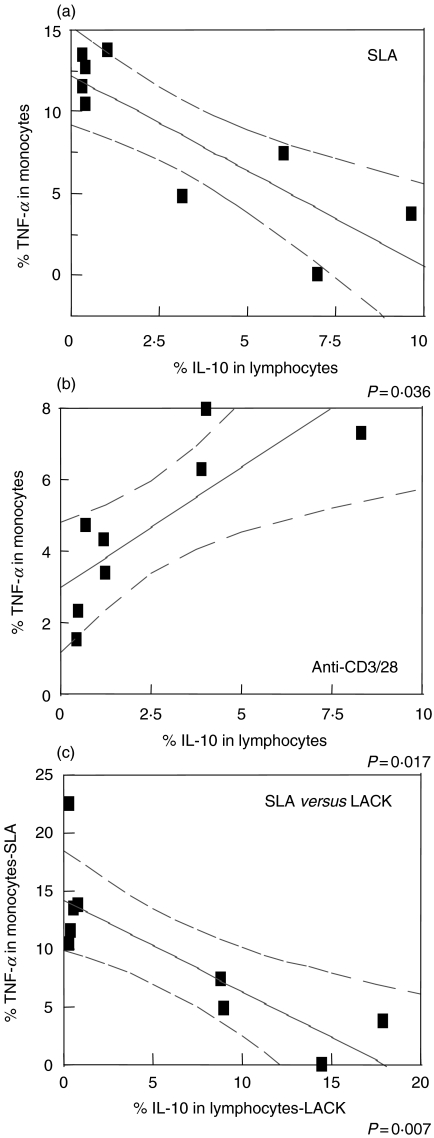

A higher frequency of parasite specific IL-10 producing lymphocytes is correlated with the down modulation of TNF-α production by monocytes

To determine the biological significance of the IL-10 producing T cells, and of their potential immunoregulatory capacity in human leishmaniasis, a correlative analysis was performed between the frequency of SLA or LACK specific, IL-10 producing lymphocytes and their likely conjugate, TNF-α producing monocytes, as an indicator of monocyte functional activity.

As demonstrated in Fig. 4a, the higher the frequency of IL-10 producing SLA specific T cells, the lower the frequency of TNF-α producing monocytes in each individual. Thus, a higher frequency of IL-10 producing SLA specific T cells, predicted a lower frequency of activated monocytes as measured by TNF-α production. In contrast, when a polyclonal stimulation is used such as anti-CD3/28, this negative correlation is lost, and in fact, reverted to a positive correlation between a higher frequency of IL-10 producing lymphocytes and a higher frequency of TNF-α producing monocytes at the level of each individual tested (Fig. 4b).

Fig. 4.

Higher frequencies of parasite specific IL-10 producing lymphocytes are correlated with the down modulation of TNF-α producing monocytes. (a) IL-10 production, obtained from the lymphocytes gate versus TNF-α production from monocytes, after culture with SLA (n = 9), and (b) anti-CD3/CD28 (n = 8). (c) IL-10 produced by blast lymphocytes stimulated with LACK versus TNF-α produced by monocytes from cultures stimulated with SLA (n = 9). PBMC from cutaneous leishmaniasis patients were stimulated as indicated for 20 h as described in Materials and Methods. The graphs show fit lines with 95% confidence curves.

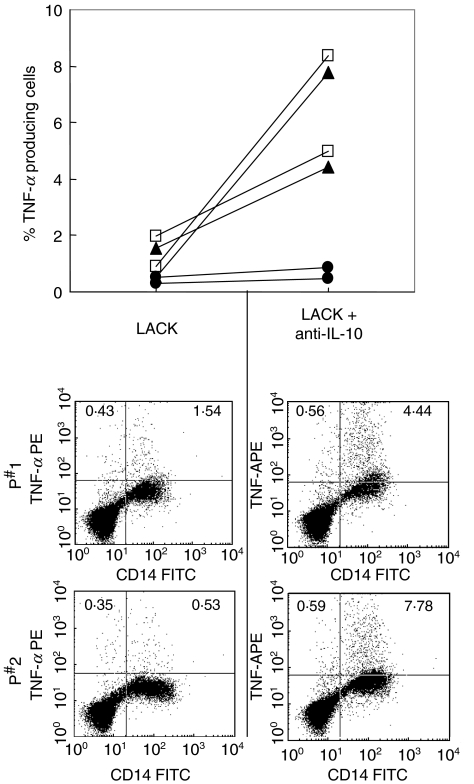

To test the role of LACK in the antigen specific induced IL-10 production by lymphocytes in response to SLA, and the subsequent reduction of TNF-α producing monocytes (Fig. 4a), correlations were performed between the frequency of IL-10 producing cells in response to LACK and the frequency of TNF-α producing monocytes in response to SLA, from independent cultures for each individual. Again, a strong negative correlation is seen between a higher frequency of IL-10 producing, LACK specific lymphocytes, and a lower frequency of TNF-α producing monocytes (Fig. 4c). Finally, to further test the biological relevance of LACK induced IL-10 in the inhibition of monocyte produced TNF-α, LACK stimulated cultures were performed in the absence or presence of anti-IL-10, and the frequency of TNF-α producing monocytes was determined (Fig. 5). The inhibitory effects of LACK induced IL-10 is clearly seen by the finding that when IL-10 is neutralized by the inclusion of anti-IL-10 antibodies, the frequency of CD14+TNF-α+ monocytes was increased in the two individuals tested.

Fig. 5.

Inhibition of LACK induced IL-10 leads to an increase in TNF-α producing monocytes. PBMC from two cutaneous leishmaniasis patients were stimulated with LACK in the presence or absence of anti-IL-10 mAb for 20 h as described in Materials and Methods. The points on the left side indicate the frequency of TNF-α producing lymphocytes for both individuals (•), or the frequency of TNF-α+/CD14 + cells (▴), or the frequency of total TNF-α producing cells (□). The corresponding points on the right side indicate the same frequencies of TNF-α producing cells from paired cultures in the presence of anti-IL-10. Below are dot plots demonstrating the frequency of TNF-α and CD14 expressing cells for both individuals from cultures with or without neutralizing anti-IL-10 antibodies.

DISCUSSION

T cell mediated immunity plays a central role in the host response to Leishmania parasites with cytokines taking an important part in developing and controlling this immune response. Cure for leishmaniasis is related to the presence of a Th1 response, leading to the production of IFN-γ and TNF-α which activate parasite-infected macrophages for parasite destruction [16]. Although the Th1 response is beneficial, the control of the inflammatory response is essential in the cure of the illness [14]. In fact, a correlation between IFN-γ and IL-10 levels has been observed for other diseases as well as in leishmaniasis [17,18]. Pompeu et al.[18] evaluated the anti-Leishmania amazonensis response of naive volunteers by using an in vitro priming system. Two groups of individuals were identified, those who produced small, and those producing large amounts of IFN-γ. The authors found that IFN-γ production was proportional to TNF-α and IL-10 production. Since IL-10 usually exhibits human macrophage-deactivating properties, high levels of IL-10 may represent a necessary counterbalance to an exacerbated polarized response, limiting tissue damage.

Several studies demonstrated cell activation and cytokine production in human leishmaniasis, however, in the present study, not only the correlation between activation/memory markers and cytokine production, but also the correlation between inflammatory and modulatory cytokines were evaluated at an individual level, offering insights to the understanding of the immunoregulatory activities of a given cell population over others and the possible role of these mechanisms in the mounting of individual immune responses during leishmaniasis.

Our data indicate that higher the frequencies of memory/experienced CD4+ T cells predicted higher commitment to SLA specific cytokine producing cells, both of inflammatory (IFN-γ) and regulatory nature (IL-10) (Figs 1b,c). While the levels of ex vivo CD45RO expression can be used to predict the intensity of the antigen specific T cell response to Leishmania parasites for both IFN-γ and IL-10 production, the commitment of this cell population to IFN-γ production is greater that to IL-10. This finding is consistent with the concept that a protective response to re-infection is seen in leishmaniasis, where activated memory T cells could play an important role in eliciting a quick efficient immune response. Based on our data, this immediate response would be dominated by IFN-γ production, which is critical for cell activation and further parasite control, and would be further controlled by the expression of the regulatory cytokine IL-10. This finding was striking considering the existing pool of memory/experienced CD4+ T cells which likely consists of T cells directed against a large gambit of foreign antigens, and not just Leishmania specific T cells. In contrast, the early activation marker (CD69) within the CD4+ T cell population was negatively correlated with the frequency of IFN-γ producing cells (Fig. 1a). An explanation for this negative correlation could be through activation-induced cell death due to the SLA reactivation in vitro after in vivo hyper-activation of specific T cells.

An approach to better understand the immunoregulation in human leishmaniasis was performed considering correlations between the frequencies of cells producing IFN-γ, TNF-α and IL-10. As expected, the higher the frequency of IFN-γ producing SLA specific CD4+ T cells, the higher the frequency of TNF-α producing SLA specific CD4+ T cells (Fig. 2c). Given that both of these cytokines are produced by Th1 like cells, this correlation indicates the effectiveness of the cellular immune response in these individuals, all of which progressed on to cure their disease. Interestingly, the higher the frequency of IFN-γ producing lymphocytes, the higher the frequency of IL-10 as well (Fig. 2a). The same outcome is observed in the blast cell population, a good indicator of the specific cellular response, following stimulation with SLA (Figs 2d,b). These findings suggest that the immunoregulatory cytokine, IL-10 is produced along with the activation cytokine, IFN-γ. This production of IL-10 may be important in the immunoregulation of the strong inflammatory response against Leishmania. Interestingly, while cytokine producing cells are correlated with one another, the absolute frequency of inflammatory cytokine producing cells is much higher then regulatory cells. This positive correlation may be due to the same cells producing both IFN-γ and IL-10 as demonstrated by Sornasse and coworkers [9].

There is evidence that the mechanisms for the cure of or the resistance to Leishmania infection are associated with macrophages activation, resulting from TNF-α and IFN-γ induced activation of free radical production, leading to the destruction of the intracellular parasites [19]. Results from our laboratory, show that oral administration of N-acetyl-l-cysteine, a glutathione precursor, leads to an increase of IFN-γ and TNF-α, a decrease of parasite number in the lesion site, and better histopathological outcome of L. major infection in BALB/c mice, demonstrating that these cytokines are essential to lesion resolution in the murine model [20]. Nevertheless IL-10 production is likely important in controlling the exacerbated inflammatory response. Our data also show a strong positive correlation between IL-10 and TNF-α producing monocytes, particullarly in stimulated cultures (Fig. 3). Thus, an intrinsic mechanism of auto-regulation by the macrophage population appears to be active in CL patients. Interestingly, the same behaviour is observed regardless of the genetically heterogeneous population of individuals analysed.

With the aim of understanding the implications of the antigen specific IL-10 producing lymphocytes on the immunoregulation of monocyte activity, correlations were preformed between IL-10 producing lymphocytes and TNF-α producing monocytes (Fig. 4). These correlation analysis demonstrated a biologically significant production of IL-10 by antigen specific lymphocytes as seen by the correlation between higher frequencies of IL-10 producing lymphocytes and lower frequencies of activated monocytes as determined by TNF-α production. Importantly, this correlation was only seen for the antigen specific (SLA or LACK) IL-10 producing lymphocytes (Fig. 4a,c), and not for polyclonal activated IL-10 production (Fig. 4b). The failure of IL-10 produced in response to the anti-CD3/28 stimulation to inhibit monocyte function may be due to the fact that the polyclonal stimulation does not require a direct conjugation between IL-10 producing lymphocytes and the monocytes, in contrast to the antigen specific stimulation. Thus, these studies demonstrate an important mechanism for antigen specific lymphocyte produced IL-10 in the regulation of TNF-α producing monocytes, as well as an ‘antigen specific delivery’ of IL-10 to the monocytes since polyclonal stimulation did not reveal the same correlation as the antigen specific response.

Bourreau and coworkers [21], studying patients with Leishmania guyanensis, show that CD4+ T cells producing IFN-γ, in response to LACK, are no longer detectable in the blood 30 days after lesion development. In contrast, IL-10 is produced in response to LACK, regardless of the time of lesion development [10]. Thus, a correlation analysis was done for verifying the biological relevance of IL-10 production against LACK and the possibility of this cytokine regulating monocyte activity. Higher IL-10 producing LACK specific CD4+ T lymphocytes correlated with a lower frequency of TNF-α producing monocytes, as measured from SLA stimulated cultures (Fig. 4). Thus, the IL-10 response against LACK beyond inhibiting TNF-α producing monocytes, may have further functional effects on the monocyte such as less efficient antigen presentation and/or parasite killing. Finally, blocking of the LACK induced IL-10 leads to an increase in the frequency of TNF-α producing monoyctes (Fig. 5).

These studies demonstrate an intricate level of control over the cytokine environment in human leishmaniasis, and demonstrate a clear interaction between various cell types leading to an overall beneficial immune response that controls the parasitic infection, while at the same time, modulating the inflammatory response. Whether this mechanism is missing in more severe forms of human leishmaniasis will be investigated.

Acknowledgments

Financial support from NIH-TMRC, WHO/TDR, PRONEX and CNPq. We thank Dr Edgar Carvalho for critical review of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barral A, Pedral-Sampaio D, Grimaldi JG, et al. Leishmaniasis in Bahia, Brazil: evidence that Leishmania amazonensis produces a wide spectrum of clinical disease. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1991;44:536–46. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1991.44.536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Karplus TM, Jeronimo SM, Chang H, et al. Association between the tumor necrosis factor locus and the clinical outcome of Leishmania chagasi infection. Infect Immun. 2002;70:6919–25. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.12.6919-6925.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mocci S, Coffman RL. Induction of a Th2 population from a polarized Leishmania-specific Th1 population by in vitro culture with IL-4. J Immunol. 1995;154:3779–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sacks DL, Noben-Trauth N. The immunology of susceptibility and resistance to Leishmania major in mice. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:845–58. doi: 10.1038/nri933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liew FY, Xu D, Chan WL. Immune effector mechanism in parasitic infections. Immunol Lett. 1999;65:101–4. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2478(98)00131-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chatelain R, Varkila K, Coffman RL. IL-4 induces a Th2 response in Leishmania major-infected mice. J Immunol. 1992;148:1182–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang ZE, Reiner SL, Zheng S, Dalton DK, Locksley RM. CD4+ effector cells default to the Th2 pathway in interferon gamma-deficient mice infected with Leishmania major. J Exp Med. 1994;179:1367–71. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.4.1367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chatelain R, Mauze S, Coffman RL. Experimental Leishmania major infection in mice: role of IL-10. Parasite Immunol. 1999;21:211–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3024.1999.00224.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sornasse T, Larenas PV, Davis KA, de Vries JE, Yssel H. Differentiation and stability of T helper 1 and 2 cells derived from naive human neonatal CD4+ T cells, analyzed at the single-cell level. J Exp Med. 1996;184:473–83. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.2.473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bottrel RL, Dutra WO, Martins FA, et al. Flow cytometric determination of cellular sources and frequencies of key cytokine-producing lymphocytes directed against recombinant LACK and soluble Leishmania antigen in human cutaneous leishmaniasis. Infect Immun. 2001;69:3232–9. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.5.3232-3239.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pingel S, Launois P, Fowell DJ, et al. Altered ligands reveal limited plasticity in the T cell response to a pathogenic epitope. J Exp Med. 1999;189:1111–20. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.7.1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coutinho SG, Pirmez C, Da Cruz AM. Parasitological and immunological follow-up of American tegumentary leishmaniasis patients. Trans R Soc Trop Med. 2002;96(Suppl. 1):S173–S178. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(02)90072-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kemp K, Theander TG, Hviid L, Garfar A, Kharazmi A, Kemp M. Interferon-gamma- and tumour necrosis factor-alpha-producing cells in humans who are immune to cutaneous leishmaniasis. Scand J Immunol. 1999;49:655–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.1999.00554.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bacellar O, Lessa H, Schriefer A, et al. Up-regulation of Th1-type responses in mucosal leishmaniasis patients. Infect Immun. 2002;70:6734–40. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.12.6734-6740.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Follador I, Araujo C, Bacellar O, et al. Epidemiologic and immunologic findings for the subclinical form of Leishmania braziliensis infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:E54–E58. doi: 10.1086/340261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Green SJ, Crawford RM, Hockmeyer JT, Meltzer MS, Nacy CA. Leishmania major amastigotes initiate the 1-arginine-dependent killing mechanism in IFN-gamma-stimulated macrophages by induction of tumor necrosis factor-alpha. J Immunol. 1990;145:4290–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boussiotis VA, Tsai EY, Yunis EJ, et al. IL-10-producing T cells suppress immune responses in anergic tuberculosis patients. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:1317–25. doi: 10.1172/JCI9918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pompeu MM, Brodskyn C, Teixeira MJ, et al. Differences in gamma interferon production in vitro predict the pace of the in vivo response to Leishmania amazonensis in healthy volunteers. Infect Immun. 2001;69:7453–60. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.12.7453-7460.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rogers KA, DeKrey GK, Mbow ML, Gillespie RD, Brodskyn CI, Titus RG. Type 1 and type 2 responses to Leishmania major. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2002;209:1–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2002.tb11101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rocha-Vieira E, Ferreira E, Vianna P, et al. Histopathological outcome of Leishmania major-infected BALB/c mice is improved by oral treatment with N-acetyl-1-cysteine. Immunology. 2003;108:401–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2003.01582.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bourreau E, Prevot G, Gardon J, et al. LACK-specific CD4(+) T cells that induce gamma interferon production in patients with localized cutaneous leishmaniasis during an early stage of infection. Infect Immun. 2002;70:3122–9. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.6.3122-3129.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]