Abstract

Burkholderia pseudomallei is a causative agent of melioidosis. This Gram-negative bacterium is able to survive and multiple inside both phagocytic and nonphagocytic cells. We previously reported that exogenous interferons (both type I and type II) enhanced antimicrobial activity of the macrophages infected with B. pseudomallei by up-regulating inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS). This enzyme thus plays an essential role in controlling intracellular growth of bacteria. In the present study we extended our investigation, analysing the mechanism(s) by which the two types of interferons (IFNs) regulate antimicrobial activity in the B. pseudomallei-infected macrophages. Mouse macrophage cell line (RAW 264·7) that was exposed simultaneously to B. pseudomallei and type I IFN (IFN-β) expressed high levels of iNOS, leading to enhanced intracellular killing of the bacteria. However, neither enhanced iNOS expression nor intracellular bacterial killing was observed when the macrophages were preactivated with IFN-β prior to being infected with B. pseudomallei. On the contrary, the timing of exposure was not critical for the type II IFN (IFN-γ) because when the cells were either prestimulated or co-stimulated with IFN-γ, both iNOS expression and intracellular killing capacity were enhanced. The differences by which these two IFNs regulate antimicrobial activity may be related to the fact that IFN-γ was able to induce more sustained interferon regulatory factor-1 (IRF-1) expression compared with the cells activated with IFN-β.

Keywords: antimicrobial activity, Burkholderia pseudomallei, IFN-β, IFN-γ, iNOS, IRF-1

INTRODUCTION

Burkholderia pseudomallei is a causative agent of melioidosis, an endemic disease in several tropical countries including south-east Asia and northern Australia [1–3]. This facultative intracellular Gram-negative bacterium is able to survive and multiply in both phagocytic and non-phagocytic cells [4]. After internalisation, B. pseudomallei can induce cell-to-cell fusion, resulting in multi-nucleated giant cell (MNGC) formation [5,6]. This phenomenon thus facilitates the spread of B. pseudomallei from one cell to another and has never been observed in any other bacteria. The mechanism(s) by which this microorganism can escape macrophage killing is not fully understood. However, we have reported that B. pseudomallei is able to invade mouse macrophages without activating inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), an essential enzyme needed to generate reactive nitrogen intermediate (RNI) which regulates survival and multiplication of intracellular bacteria [7].

Several cytokines including both type I [interferon (IFN)-β] and type II (IFN-γ) interferons have been reported to enhance iNOS expression [8,9]. Mouse macrophages prestimulated with IFN-γ could up-regulate iNOS expression in the cells infected with B. pseudomallei and this process, in turn, enhanced the intracellular killing of the bacterium [7]. The protective activity of IFN-γ has also been demonstrated in mice infected with B. pseudomallei[10]. Recently, we reported that exogenous IFN-β added simultaneously to the culture of mouse macrophages at the time of exposure to B. pseudomallei could also enhance the level of iNOS expression which increased the antimicrobial activity of B. pseudomallei-infected macrophages [11].

It is well documented that expression of interferon regulatory factor-1 (IRF-1) and the presence of IRF-1 binding site within the promoter region of the iNOS gene are necessary for the induction of iNOS expression in murine macrophages [12,13]. IRF-1 is not normally expressed in unstimulated murine macrophages. However, IRF-1 expression can be induced by a variety of stimuli including IFN-β and IFN-γ[13–16]. In this study, we demonstrated that the mechanism by which these two IFNs regulate the antimicrobial activity of B. pseudomallei-infected macrophages is distinct from one another.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell line and culture condition

Mouse macrophage cell line (RAW 264·7) was obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Rockville, MD, USA). If not indicated otherwise, the cells were cultured in Dulbeccco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM) (Gibco Laboratories, Grand Island, NY, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (HyClone, Logan, UT, USA) at 37°C under a 5% CO2 atmosphere.

Bacterial isolation

B. pseudomallei strain 844 (arabinose-negative biotype) used in this study was originally isolated from a patient admitted to Srinagarind hospital in the melioidosis endemic Khon Kaen province of Thailand. The bacterium was identified originally as B. pseudomallei based on its biochemical characteristics, colonial morphology on selective media, antibiotic sensitivity profiles and reactivity with polyclonal and monoclonal antibodies [17–19].

Protocol for activation of B. pseudomallei-infected mouse macrophage cell line (RAW 264·7)

In order to prestimulate mouse macrophages with IFNs, the cells (1 × 106 cells) were cultured in a six-well plate in the presence of IFN-β (100 U/ml) or IFN-γ (10 U/ml) for 18 h and then excess IFNs were removed by washing with phosphate buffered saline (PBS). For the co-stimulation experiments, the macrophages were exposed to either IFN-β or IFN-γ at the time of infection. Thereafter, the protocols for both prestimulation and co-stimulation experiments were the same. In brief, the IFN-treated macrophages were exposed to B. pseudomallei at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 2 : 1 for 1 h. Excess bacteria were removed by washing three times with 2 ml of PBS. Residual extracellular bacteria that might adhere to the cell surface were killed by incubating with DMEM containing 250 µg/ml of kanamycin (Gibco Laboratories) for 2 h before switching to the medium containing 20 µg/ml of kanamycin.

Standard antibiotic protection assay

To determine intracellular survival and multiplication of the bacteria, a standard antibiotic protection assay was performed as described previously [7]. The macrophages (1 × 106) were cultured overnight in a 24-well plate and then exposed to bacteria at MOI of 2 : 1. After 1 h of incubation, extracellular bacteria were removed and the cells were washed three times with 2 ml of PBS. Residual bacteria that adhered to the cell surface were killed by incubating in DMEM containing 250 µg/ml of kanamycin for 2 hrs before incubating further in DMEM containing 20 µg/ml of kanamycin. Eight hours after infection, the cells were washed three times with PBS and intracellular bacteria were liberated by lysing the macrophages with 0·1% Triton X-100 and plating the released bacteria in tryptic soy agar. The number of intracellular bacteria, expressed as colony forming units (CFU), was determined by bacterial colony counting.

Quantification of multinucleated giant cells (MNGCs) in B. pseudomallei-infected macrophages

In order to quantify the degree of MNGC formation, the macrophages (1 × 106) were first cultured overnight on a coverslip as described previously [6]. After 1 h of incubation with B. pseudomallei at MOI of 2 : 1, the macrophages were washed three times with PBS and then incubated in DMEM containing 250 µg/ml of kanamycin for 2 h to kill residual extracellular bacteria. The macrophages were incubated further in DMEM containing 20 µg/ml of kanamycin as indicated above. At 4, 6 and 8 h after infection the coverslips were washed with PBS, fixed for 15 min with 1% paraformaldehyde and then washed sequentially with 50% and 90% ethanol for 5 min each. The coverslips were air-dried before staining with Giemsa [6]. For enumeration of the MNGC formation, at least 1000 nuclei per coverslip were counted using light microscope at a magnification of 40× and the percentage of multi-nucleated cells was calculated [6]. The MNGC was defined as the cell possessing more than one nuclei within the same cell boundary.

Immunoblotting

Mouse macrophage preparations were lysed in buffer containing 20 mm Tris, 100 mm NaCl and 1% NP40. The lysates containing 30 µg of protein were electrophoresed on SDS-PAGE at 10% polyacrylamide and then electrotransferred to nitrocellulose membrane (Schleicher & Schuell, Dassel, Germany). The membrane was blocked with 5% milk for 1 h before incubating overnight with polyclonal rabbit antibody to mouse iNOS or IRF-1 (Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, CA, USA). The blots were then allowed to react with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated swine antirabbit IgG (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark). Protein bands were detected by enhanced chemiluminescence as recommended by the manufacturer (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany).

RESULTS

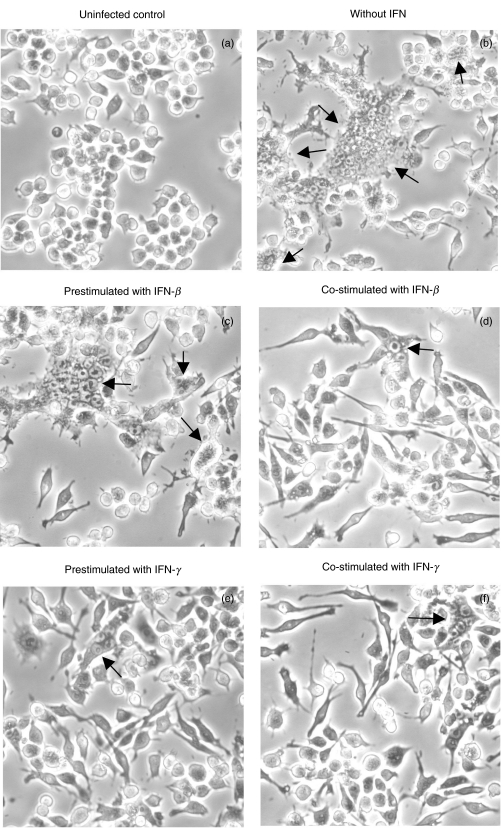

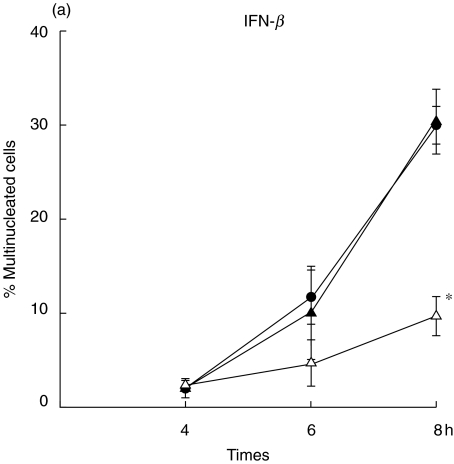

One of the unique characteristics of B. pseudomallei is its ability to induce a cell-to-cell fusion leading to MNGC formation and the extensiveness of MNGC formation parallels with the severity of infection by B. pseudomallei[6]. In order to distinguish the regulatory mechanism of these two types of IFNs on bacterial induced pathology, mouse macrophage cell lines (RAW 264·7) were either preactivated with the IFN for 18 h (prestimulated) or simultaneously activated (co-stimulated) at the time of infection with B. pseudomallei. Eight hours after the infection, the infected cells were visualized under inverted microscope (40×). As shown in Fig. 1, the MNGC formation (indicated by arrow) could be observed readily in the controlled unactivated macrophages infected with B. pseudomallei (Fig. 1b). The MNGC formation was observed only sparingly in the experiment where the cells were co-stimulated with IFN-β (Fig. 1d) and the cell culture exhibited a morphology which was not noticeably different from the uninfected control (Fig. 1a). Unlike the results described from the co-stimulation experiment, a high number of MNGC formation could be observed in the cultures which were prestimulated with IFN-β prior to being infected with B. pseudomallei (Fig. 1c). In contrast to the results noted with the IFN-β, the degree of MNGC formation was reduced markedly in the cells that were either pre- or co-stimulated with IFN-γ, indicating that the IFN-γ was effective in activating the cells regardless of the time of exposure. To be quantitative, the number of MNGC was quantified after Giemsa staining (Fig. 2). At 8 h, the number of MNGC was as high as 30% in unactivated B. pseudomallei-infected macrophages and this number was reduced significantly to less than 10% with the IFN-β co-stimulation (P ≤ 0·05) (Fig. 2a). However, preactivating the macrophages with IFN-β prior to the time of bacterial exposure did not reduce the number of MNGC. In contrast to IFN-β, the cells that were either prestimulated or co-stimulated with IFN-γ showed significantly lower numbers of MNGC formation compared with the unactivated B. pseudomallei-infected macrophages (P ≤ 0·05) (Fig. 2b).

Fig. 1.

Effect of IFN-β and IFN-γ on MNGC formation induced by B. pseudomallei. Mouse macrophage cell line (RAW 264·7) (1 × 106 cells/well) was either prestimulated with IFN (100 U/ml of IFN-β or 10 U/ml of IFN-γ) for 18 h (c) and (e) or simultaneously co-stimulated (d) and (f) with B. pseudomallei (MOI 2 : 1). After 8 h, the cells were visualized under inverted microscope (20×). Uninfected cells (a) and B. pseudomallei-infected cells alone without IFN (b) were included for comparison. MNGC formation is indicated by arrow.

Fig. 2.

Quantification of MNGC formation induced by B. pseudomallei. The macrophages were either prestimulated (▴) with IFN (100 U/ml of IFN-β)(a)or 10 U/ml of IFN-γ(b)for 18 h or simultaneously (n) co-stimulated with B. pseudomallei (MOI 2 : 1). The B. pseudomallei-infected macrophages without IFN stimulation served as control (•). At 4, 6 and 8 h post-infection, the cells were fixed, stained with Giemsa, and the number of MNGC was determined by microscopic examination (40×). Data represent mean and s.d. of three separate experiments, each carried out in duplicate. *P ≤ 0·05 by Student's t-test.

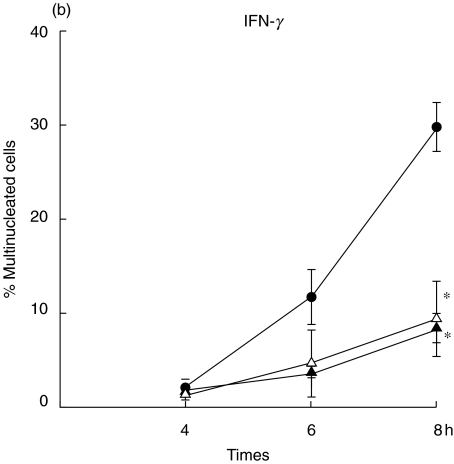

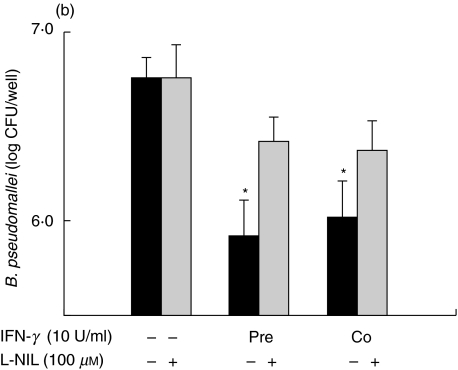

The degree of MNGC formation induced by B. pseudomallei was reported to correlate directly with the number of intracellular survival of this bacterium [11]. In order to compare the ability of IFN-β and IFN-γ to activate macrophages, judging by their ability to kill intracellular B. pseudomallei, standard antibiotic protection assay was used. Consistent with the results based on reduction of the MNGC formation, the IFN-β was able to enhance antimicrobial activity of the macrophages infected with B. pseudomallei only under the co-stimulation condition (Fig. 3a). Again, prestimulating the cells with IFN-β did not increase its intracellular killing capacity. On the contrary, the cells that were either preactivated or co-activated with IFN-γ exhibited a significantly lower number of viable intracellular bacteria (Fig. 3b). The enhanced antimicrobial activity against B. pseudomallei by either IFN-β or IFN-γ was abrogated when a specific iNOS inhibitor,L-NIL, was added to the cell culture (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

IFNs inhibit intracellular survival of B. pseudomallei in mouse macrophages. Macrophages were prestimulated with either 100 U/ml of IFN-β(a)or 10 U/ml of IFN-γ(b)for 18 h or co-stimulted simultaneously with B. pseudomallei (MOI 2 : 1). The experiment was carried out either without or with L-NIL (100 µm) which was added to the cells 2 h prior to the bacterial infection and kept in the culture medium until the experiment was terminated. At 8 h post-infection, the number of intracellular B. pseudomallei was determined by standard antibiotic protection assay as described in Materials and methods. Data represent mean and s.d. of three separate experiments, each carried out in duplicate. *P < 0·05 by Student's t-test.

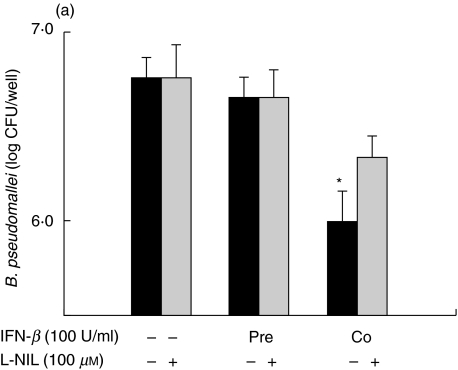

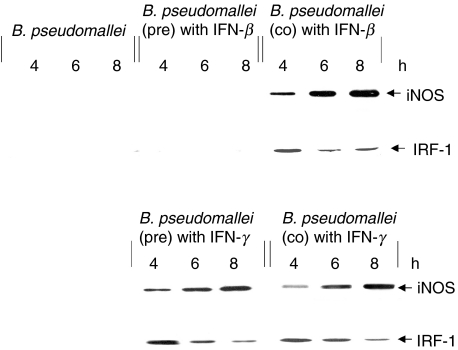

The ability of L-NIL to suppress antimicrobial activity in IFN-activated macrophages prompts us to investigate the regulation of iNOS and IRF-1 in B. pseudomallei infection. The expression of iNOS and IRF-1 was determined from the lysate of the infected cells by immunoblotting using antibody against iNOS and IRF-1, respectively. As shown in Fig. 4, exposure to B. pseudomallei by itself was not sufficient to stimulate the expression of either iNOS or IRF-1. However, the expression of both iNOS and IRF-1 were observed when the cells were co-stimulated with IFN-β. Consistent with the results of MNGC formation and intracellular killing presented above, the cells which were preactivated with IFN-β prior to being infected with B. pseudomallei expressed neither iNOS nor IRF-1. In contrast, the macrophages which were either prestimulated or co-stimulated with IFN-γ were able to produce both iNOS and IRF-1. Altogether, the data presented showed that the expression of iNOS paralleled the activation of the transcription factor IRF-1 in the B. pseudomallei-infected macrophages. It should be mentioned that the macrophages activated with the IFN alone were not able to up-regulate iNOS (data not shown).

Fig. 4.

IFNs induce expression of iNOS and IRF-1 in B. pseudomallei infected macrophages. Mouse macrophages were prestimulated with either 100 U/ml of IFN-β or 10 U/ml of IFN-γ for 18 h before or co-stimulated at the time of exposure to B. pseudomallei (MOI 2 : 1). At 4, 6 and 8 h post-infection, the cells were lysed with lysis buffer and cell lysate was subjected to immunoblotting using anti-iNOS and anti-IRF-1.

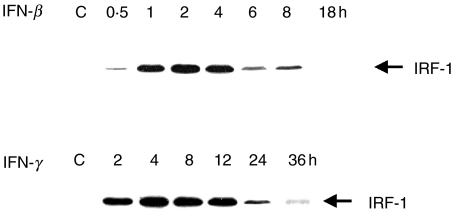

It is well documented that both IFN-β and IFN-γ, alone, can stimulate a significant degree of IRF-1 expression [15]. The presence of this transcription factor is required for iNOS gene transcription. We therefore analyse the way by which these two IFNs differentially regulate the IRF-1 expression by immunoblot. In this experiment, the IFN was added to uninfected macrophages and the levels of IRF-1 expression in the lysate were followed by immunoblotting as described. The results presented in Fig. 5 demonstrated that the expression of IRF-1 in the macrophages stimulated with IFN-β gradually increased and reached a maximum after 2–4 h before being degraded and finally disappeared altogether by 18 h. Unlike the IFN-β, IFN-γ was not only able to stimulate IRF-1 but in addition it was also able to sustain the activation state of IRF-1 for a period as long as 24 h. In fact, a trace of IRF-1 expression could be detected at 36 h, when the experiment was terminated. It should be noted that in the unstimulated cells, neither IRF-1 nor iNOS were observed by the immunoblotting (data not shown).

Fig. 5.

Kinetics of IRF-1 expression from the macrophages activated with IFNs. Mouse macrophages were stimulated with either IFN-β (100 U/ml) or IFN-γ (10 U/ml). At different time intervals, the cells were lysed with lysis buffer and cell lysate was subjected to immunoblotting using anti-IRF-1.

DISCUSSION

Inducible nitric oxide synthase is known to play a significant role in host defence against a number of microbial infections. Intracellular microbial killing is often associated with the expression of iNOS and NO [20]. When Leishmania major promastigotes were injected into the peritoneal cavity of wild-type (iNOS+/+) and iNOS-knock-out (iNOS–/–) mice, 40-fold more parasites was recovered from the knock-out mice 24 h after the parasite injection [21]. In other models, the survival rate of iNOS–/– mice infected with Listeria monocytogenes and Mycobacterium tuberculosis was also reduced compared with the wild-type counterpart, indicating that iNOS is an essential enzyme in protective immunity against these bacterial infections [22,23]. The expression of iNOS could be differentially regulated by different microbial products. In addition to live bacteria, bacterial components such as endotoxin, lipoproteins or exotoxins could also effectively stimulate macrophages to express iNOS [9]. The iNOS expression from the macrophages infected with microbes or exposed to microbial products could be further enhanced by cytokines such as IFN-β and IFN-γ. In the mouse macrophages activated with ManLam (the cell wall lipoglycan of M. tuberculosis) or lipopolysaccharide (LPS) from Gram-negative bacteria, the expression of iNOS and NO production was greatly increased in the presence of IFN-γ or IFN-β[11,24–26]. In contrast to IFN-γ, a specific sequence of stimulation by IFN-β is required for up-regulating iNOS expression. Only simultaneous exposure of the macrophages to IFN-α/β and L. major promastigotes also enhanced the induction of iNOS, thus resulting in increased anti-leishmanial activity of these macrophages [27].

Unlike most other bacteria that have been examined, B. pseudomallei by itself fails to stimulate iNOS expression in macrophages [7]. The failure to induce the expression of this enzyme may be related to the fact that B. pseudomallei possess LPS which is different from that of other Gram-negative bacteria and it is also a poor macrophage activator [28]. The inability of B. pseudomallei-infected macrophages to produce iNOS would allow this bacterium to survive and multiply intracellularly. However, in the presence of IFN-γ, iNOS expression could be up-regulated, thus enhancing the intracellular killing of B. pseudomallei[7,29]. The protective roles of IFN-γ in mice infected with B. pseudomallei have also been demonstrated [10]. Recently, we reported that IFN-β could also enhance the macrophage ability to kill intracellular B. pseudomallei by up-regulating iNOS expression [11]. Although both IFN-γ and IFN-β could activate microbicidal activity of macrophages, in the present study we demonstrated the evidence showing that the two IFNs possess different regulatory mechanisms on iNOS expression. With regard to the IFN-β, the up-regulation of iNOS in the macrophages infected with B. pseudomallei was observed only in the co-stimulating situation which paralleled the increase of the intracellular killing (Fig. 3), simultaneously decreasing MNGC formation (Figs 1 and 2).

The inability of IFN-β to enhance iNOS expression from the macrophages infected with B. pseudomallei when the cells were prestimulated with this cytokine may be related to the fact that IFN-β was unable to sustain the activation of IRF-1 expression, like the cells prestimulated with IFN-γ. IRF-1 is a crucial transcriptional activator which binds to the sites within the promoter region of the iNOS gene [12,13]. In IRF-1 knock-out (IRF–/–) mice, the animals were more susceptible to bacterial infection than the wild-type and this is probably related to the fact that the IRF–/–mice were unable to produce NO even in the presence of IFN-γ[12]. The role of IRF-1 in regulating iNOS expression has also been demonstrated in vitro. In the presence of antibody against IFN-β, the mouse macrophages infected with Salmonella typhi failed to produce IRF-1, resulting in a significant decrease of iNOS expression [11]. When the cells that were prestimulated with IFN-β prior to the B. pseudomallei infection, these cells were not able to express either iNOS or IRF-1 protein. On the other hand, when the cells were prestimulated with IFN-γ and followed by exposure to living B. pseudomallei, high levels of both iNOS and IRF-1 were observed. In this communication, we extended our finding to demonstrate that the kinetics of IRF-1 expression induced by IFN-β is distinct from that of the IFN-γ (Fig. 5). IFN-β can stimulate IRF-1 expression and sustains it for only a short period. In contrast, the macrophages stimulated with IFN-γ were able to maintain the IRF-1 level for more than 36 h after activation. The difference in IRF-1 expression may be due to the fact that IFN-β and IFN-γ use different molecules to transduce the signal [30,31]. The difference in signalling pathways between IFN-β and IFN-γ may result in different kinetics of IRF-1 expression. The results presented reveal new information on innate immune mechanism and the way in which we may immunomodulate the host to respond favourably to severe infection and sepsis such as that caused by B. pseudomallei.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by research grants from Thailand Research Fund and Chulabhorn Research Institute (Thailand). We thank Mr Maurice Broughton (Faculty of Science, Mahidol University) for editing the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dharakul T, Songsivilai S. The many facets of melioidosis. Trends Microbiol. 1999;7:138–46. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(99)01477-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leelarasame S, Bovonkitti S. Melioidosis: review and update. Rev Infect Dis. 1989;11:413–25. doi: 10.1093/clinids/11.3.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yabuuchi E, Arakawa M. Burkholderia pseudomallei and melioidosis: be aware in temperate area. Microbiol Immunol. 1993;37:823–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1993.tb01712.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jone A, Beveridge TJ. Woods DE. Intracellular survival of Burkholderia pseudomallei. Infect Immun. 1996;64:782–90. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.3.782-790.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harley VS, Dance DAB, Drasar BJ, Tovey G. Effects of Burkhoderia pseudomallei and other Burkhoderia species on eukaryotic cells in tissue culture. Microbios. 1998;96:71–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kespichayawattana W, Rattanachetkul S, Wanun T, Utaisincharoen P, Sirisinha S. Burkholderia pseudomallei induces cell fusion and actin-associate membrane protusion: a possible mechanism for cell-to-cell spreading. Infect Immun. 200(68):5377–84. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.9.5377-5384.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Utaisincharoen P, Tangthawornchaikul N, Kespichayawattana W, Chaisuriya P, Sirisinha S. Burkholderia pseudomallei interferes with inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) production: a possible mechanism of evading macrophage killing. Microbiol Immunol. 2001;45:307–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2001.tb02623.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bogdan C, Rollinghoff M, Difenbach A. Reactive oxygen and reactive nitrogen intermediate in innate and specific immunity. Curr Opin Immunol. 2000;12:64–76. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(99)00052-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bogdan C, Rollinghoff M, Diefenbach A. The role of nitric oxide in innate immunity. Immunol Rev. 2000;173:17–26. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2000.917307.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Santanirad P, Harley VS, Dance DAB, Drasar BS, Bancroft GJ. Obligatory role in gamma interferon for host survival in murine model of infection with Burkholderia pseudomallei. Infect Immun. 1999;67:3593–600. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.7.3593-3600.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Utaisincharoen P, Anuntagool N, Limposuwan K, Chaisuriya P, Sirisinha S. Involvement of IFN-β in enhancing inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) production and antimicrobial activity of B. pseudomallei infected macrophages. Infect Immun. 2003;71:3053–7. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.6.3053-3057.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kamijo R, Harda H, Matsuyama T, et al. Requirement for transcription factor IRF-1 in NO synthase induction in macrophages. Science. 1994;263:1612–5. doi: 10.1126/science.7510419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martin E, Nathan C, Xie QW. Role of interferon regulatory factor in induction of nitric oxide synthase. J Exp Med. 1994;180:977–84. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.3.977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jacob AT, Ignarro LJ. LPS-induced expression of IFN-β mediated the timing of iNOS induction in RAW 264.7 macrophages. J Biol Chem. 2001;51:47950–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106639200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Taniguchi T, Ogasawara K, Takaoka A, Tanaka N. IRF family of transcription factors as regulators of host defense. Ann Rev Immunol. 2001;19:623–55. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miyamoto M, Fujita T, Kimura Y, et al. Regulated expression of a gene encoding a nuclear factor, IRF-1, that specifically binds to IFN-β gene regulatory element. Cell. 1988;54:903–13. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(88)91307-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anuntagool N, Intachote P, Wuthiekanun N, White NJ, Sirisinha S. Lipopolysaccharide from nonvirulent Ara+Burkholderia pseudomallei isolates is immunologically indistinguishable from lipopolysaccharide from virulent Ara– clinical isolate. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1998;5:225–9. doi: 10.1128/cdli.5.2.225-229.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kawahara K, Dejsirilert S, Danbara H, Ezaki T. Extraction and characterization of lipopolysaccharide from Pseudomonas pseudomallei. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1992;96:129–34. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(92)90392-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wuthiekanun V, Smith MD, Dance DAB, Walsh AL, Pitt TL, White NJ. Biochemical characteristics of clinical and environmental isolates of Burkholderia pseudomallei. J Med Microbiol. 1996;45:408–12. doi: 10.1099/00222615-45-6-408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.MacMicking J, Xie Q, Nathan C. Nitric oxide and macrophages function. Ann Rev Immunol. 1997;15:323–50. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.15.1.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Diefenbach A, Schindler H, Donhauser N, et al. Type I interferon (IFN alpha/beta) and type 2 nitric oxide synthase regulate the innate immune response to a protozoan parasite. Immunity. 1998;8:77–87. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80460-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.MacMicking J, North R, LaCourse R, Mudgett J, Shah S, Nathan C. Identification of NOS2 as a protective locus against tuberculosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:5243–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.10.5243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.MacMicking J, Nathan C, Hom G, et al. Altered responses to bacterial infection and endotoxic shock in mice lacking inducible nitric oxide synthase. Cell. 1995;81:641–50. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90085-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chan E, Morris K, Belisle J, et al. Induction of inducible nitric oxide synthase-NO by lipoarabinomannan of Mycrobacterium turberculosis is mediated by MEK1-ERK, MKK7-JNK, and NF-κB signaling pathway. Infect Immun. 2001;69:2001–10. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.4.2001-2010.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lorsbach R, Russell S. A specific sequence of stimulation is required to induce synthesis of the antimicrobial molecule nitric oxide by mouse macrophages. Infect Immun. 1992;60:2133–5. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.5.2133-2135.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang X, Alley E, Russell S, Morrison D. Necessity and sufficiency of beta interferon for nitric oxide production in mouse peritoneal macrophages. Infect Immun. 1994;62:33–40. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.1.33-40.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mattner J, Schindler H, Diefenbach A, Rollinghoff M, Gresser I, Bogdan C. Regulation of type 2 nitric oxide synthase by type I interferon in macrophages infected with Leishmania major. Eur J Immunol. 2000;30:2257–67. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(2000)30:8<2257::AID-IMMU2257>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Utaisincharoen P, Tangthawornchaikul N, Kespichayawattana W, Anuntagool N, Chaisuriya P, Sirisinha S. Kinetic studies of the production of nitric oxide and tumor necrosis factor-alpha in macrophages stimulated with Burkholderia pseudomallei endotoxin. Clin Exp Immunol. 2000;122:324–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2000.01386.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miyagi K, Kawakami K, Saito A. Role of reactive nitrogen and oxygen intermediates in gamma interferon stimulated murine macrophage bactericidal activity against Burkholderia pseudomallei. Infect Immun. 1997;67:4108–13. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.10.4108-4113.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shtrichman R, Samuel C. The role of gamma interferon in antimicrobial immunity. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2001;4:251–9. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(00)00199-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Decker T, Stockinger S, Karaghiosoff M, Muller M, Kovarik P. IFNs and STATs in innate immunity to microorganisms. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:1271–7. doi: 10.1172/JCI15770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]