Abstract

Mannose-binding lectin (MBL) is a key element in innate immunity with functions and structure similar to that of complement C1q. It has been reported that MBL deficiency is associated with occurrence of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). We hypothesized that anti-MBL antibodies, if present, would affect the occurrence or disease course of SLE, by reduction of serum MBL levels, interference of MBL functions, or binding to MBL deposited on various tissues. To address this hypothesis, we measured the concentration of anti-MBL antibodies in sera of 111 Japanese SLE patients and 113 healthy volunteers by enzyme immunoassay. The titres of anti-MBL antibodies in SLE patients were significantly higher than those in healthy controls. When the mean + 2 standard deviations of controls was set as the cut off point, individuals with titres of anti-MBL antibodies above this level were significantly more frequent in SLE patients (9 patients) than in controls (2 persons). One SLE patient had an extremely high titre of this antibody. No associations of titres of anti-MBL antibodies and (i) genotypes of MBL gene, (ii) concentrations of serum MBL, or (iii) disease characteristics of SLE, were apparent. Thus, we have confirmed that anti-MBL antibodies are indeed present in sera of some patients with SLE, but the significance of these autoantibodies in the pathogenesis of SLE remains unclear.

Keywords: Lupus/systemic lupus erythematosus, autoantibodies, MBL, C1q, polymorphisms

INTRODUCTION

Both genetic and environmental factors are important in the development of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), a systemic autoimmune disease of unknown origin [1,2]. With respect to genetic background, deficiencies in components of the classical pathway of complements (C1q, C1r, C1s, C4 or C2) are known to be major predisposing risk factors for SLE [3–6]. In complement deficiencies, an abnormal clearance of not only immune complexes [3], but also apoptotic cells, has been suggested as contributive towards the occurrence of SLE [7]. Inappropriate levels of apoptotic nuclei are suggested to be a source of autoantigens in SLE [8].

Mannose-binding lectin (MBL) comprises a trimer of three identical polypeptides, and several trimers further combine to form a bouquet-like structure resembling C1q [9]. The MBL gene is located on the long arm of chromosome 10 at 10q11.2-q21 and contains 4 exons [10]. Several polymorphisms have been reported for the MBL gene, and a large interindividual difference in serum MBL concentration among test subjects is caused by the possession of variant alleles. Codon 52, 54 and 57 polymorphisms are all on exon 1, and the presence of any of the minority alleles results in a significant reduction of the serum MBL concentration. Furthermore, homozygosity for minority alleles results in almost complete deficiency of serum MBL [11,12]. This has been attributed to increased degradation of the mutated protein [12]. In the promoter region of the MBL gene, polymorphisms are reported at positions −550, −221 and + 4, and they also greatly influence the levels of serum MBL [13,14]. MBL mediates lectin-dependent activation of the complement pathway [9], and plays an important role in host defense against microorganisms by phagocytosis. Individuals lacking this protein could develop severe episodes of bacterial infections from early life [15–17].

Recently, several studies have suggested that MBL deficiency, or low serum MBL levels caused by polymorphisms in the structural portion or promoter region of the MBL gene, may be associated with occurrence of SLE [18–22]. Two possible explanations for the associations between MBL deficiency and the occurrence of SLE are suggested. Firstly, MBL can bind to and initiate uptake of apoptotic cells by macrophages [23], and an abnormal clearance of apoptotic cells caused by MBL deficiency may result in the overexpression of autoantigens. Alternatively, viral infection is believed to be one of causes of SLE [24–26], and MBL deficiency may lead to more frequent infections. On the other hand, deposits of MBL were found in glomerular tissues of SLE patients [27,28], and d-mannose and N-acetylglycosamine, both possible ligands for MBL, are present in the salivary glands of patients with Sjögren's syndrome [29]. In this situation, MBL may have a pathogenic role during the course of SLE.

It has been reported that autoantibodies to C1q are associated with hypocomplementemia and glomerulonephritis [30]. If autoantibodies to MBL, a molecule similar to C1q in structure and functions, are present in patients with SLE, they may: reduce MBL levels; interfere with MBL functions; or bind to MBL deposited to various diseases. We investigated whether anti-MBL antibodies are indeed present in sera of Japanese patients with SLE.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients and controls

Samples used for the study were taken from 111 Japanese patients with SLE, at Division of Rheumatology, Department of Internal Medicine, University Hospital of Tsukuba, Japan. All patients fulfilled the 1997 American College of Rheumatology (ACR) Classification Criteria for SLE. Patients with drug-induced lupus were excluded. The study was approved by the local ethics committee, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants of this study. Medical information including clinical manifestations, and laboratory data were collected simultaneously with sampling. Samples from 113 Japanese healthy volunteers served as controls.

Detection of immunoglobulin G (IgG) binding to MBL

Sumilon S plates (Sumitomo Bakelite, Tokyo Japan) were coated overnight at 4°C with 100 µl/well of recombinant MBL [31] in a carbonate/bicarbonate-buffer (pH 9·6) at a concentration of 1 µg/ml. The plates were washed three times with tris-buffered saline (TBS, pH 7·4) containing 0·05% Tween-20 (TBS/Tw). Unoccupied binding sites were blocked by incubation with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in TBS for 1 h at 37°C. One hundred µl/well of serum samples diluted to 1 : 50 in TBS/Tw containing 0·3% BSA and 1 mm EDTA were added to the wells, and the plates were incubated overnight at 4°C. EDTA was included to inhibit the Ca2+ dependent binding of MBL to carbohydrates present on the Fc portion of IgG. All samples were analysed in triplicates. After incubation, 100 µl/well alkaline phosphate (AP)-conjugated goat antihuman IgG, specific for Fab fragment (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) diluted 1 : 5000 in TBS/Tw, was added to each well. The microtiter plates were incubated for 1 h at room temperature. Subsequently, alkaline phosphate substrate (Sigma) was added to each well. The plates were incubated for 2 h at room temperature. Optical densities (OD) were measured at 405 nm. The concentration of IgG reactive with MBL is expressed in units/ml of serum (U/ml), where the concentration in a standard sample was defined as 1000 U/ml. Standard curves were generated in all assays performed.

Inhibition assays

Anti-MBL positive sera diluted to 1 : 50 were preincubated with TBS or recombinant MBL at concentrations from 0·1563 µg/ml to 10 µg/ml at room temperature for 1 h. The samples were then put onto MBL-coated plates, and IgG binding to MBL was measured as described above.

Typing of the MBL gene

Genomic DNA was purified from peripheral blood leucocytes using the DnaQuick DNA purification kit (Dainippon Pharmaceuticals, Osaka, Japan), and stored at −30°C. Typing of the MBL gene allele was performed by using the polymerase chain reaction- restriction fragment length polymorphism method according to the methods of Madsen et al. [11]. The wild-type allele was designated as allele A, and codon 54 substitution (glycine to aspartic acid) was designated as allele B. Previous studies have shown that codon 52 and 57 polymorphisms are not present or extremely rare in the Japanese population [32,33].

Measurement of the serum MBL concentration by enzyme immunoassay

Serum concentration of MBL was measured by a specific enzyme immunoassay utilizing two rabbit polyclonal anti-MBL antibodies as described previously [31]. All samples were stored at −80°C and no previous freeze/thaw was done.

Statistics

Mann–Whitney U-test, Fisher's exact test, chi-square analysis and Spearman's rank correlation test were used. P-values of <0·05 were considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

Detection of autoantibodies to MBL in patients with SLE

Titers of IgG reactive with human MBL in patients with SLE were significantly higher than those in healthy controls; P < 0·0001, median MBL concentration ± standard deviation (s.d.); 47·4 ± 49·3 and 30·6 ± 29·2, in SLE patients and healthy controls, respectively (Fig. 1). The assay was performed in the presence of EDTA in order to inhibit the binding between the carbohydrate recognition domain of MBL and carbohydrates on the Fc portion of IgG. Furthermore, selected samples were digested with pepsin and F(ab′)2 fragments were purified. F(ab′)2 fragments did bind to MBL coated plates, indicating that IgG–MBL interaction detected in this assay is indeed antigen-antibody binding (results not shown). We found a patient with an extremely high level of serum anti-MBL, and the titre of anti-MBL antibodies in the serum of this patient was designated 1000 U/ml. The number of subjects having a titre of more than 2 sd. above the average of healthy controls (89·5, indicated by dotted line in Fig. 1) was 9 of the patients with SLE, and 2 of the healthy controls. This difference was statistically significant (P = 0·0341 by Fisher's exact test).

Fig. 1.

Autoantibodies to mannose-binding lectin (MBL) in serum samples. Anti-MBL antibodies were measured in 111 samples from patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and in 113 samples from healthy controls, in the presence of EDTA (1 mm). Dotted line indicates 2 standard deviation (s.d.) above average in healthy controls. P-value by Mann–Whitney U-test. aU, arbitrary units.

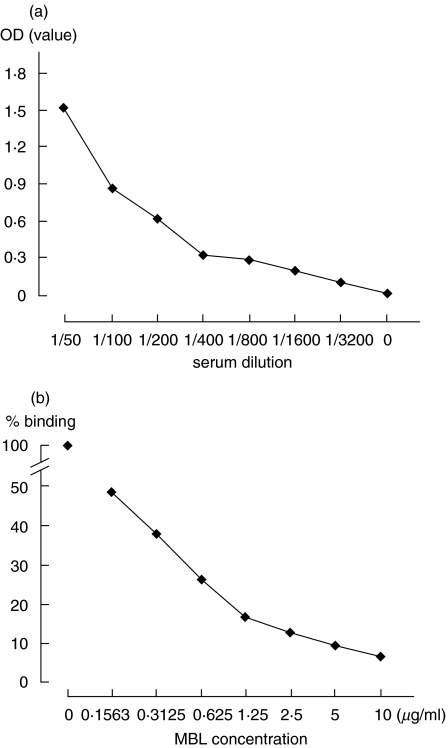

A titration curve could be adequately drawn using serial dilutions of the standard serum (Fig. 2a). In addition, adding excess amounts of recombinant MBL to diluted standard serum inhibited the binding of IgG to solid phase MBL in a dose dependent manner (Fig. 2b).

Fig. 2.

Titration curve and inhibition assay for autoantibodies to mannose-binding lectin (MBL). (a) Titration curve for anti-MBL antibodies using serial dilutions of the standard serum in the presence of EDTA (1 mm). (b) Inhibition assay for anti MBL antibodies adding excess amount of recombinant MBL to diluted standard serum in the presence of EDTA (1 mm).

Associations between levels of anti-MBL antibodies, and MBL gene genotypes or serum concentrations of MBL in patients with SLE

Serum MBL concentrations reflected the MBL genotype of the individual in accordance with previous reports (Fig. 3) [11,12]. Serum MBL concentrations in SLE patients were not significantly different from those in healthy individuals (P = 0·5296). Among individuals with the same genotype, SLE patients tended to have higher MBL concentrations than controls, but without statistical significance (AA; P = 0·3385, AB; P = 0·5556, BB; P = 0·1573 by Mann–Whitney's U-test).

Fig. 3.

Serum mannose-binding lectin (MBL) concentrations in 111 patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and 113 healthy controls. Subjects with homozygosity for the codon 54 wild-type allele (□), subjects with heterozygosity for the codon 54 variant (▪), and subjects with homozygosity for the codon 54 variant allele (Δ) are indicated in both patients with SLE and healthy controls. Dotted lines indicate average of titres of serum MBL concentrations in each genotype on both groups. P-value by Mann–Whitney U-test.

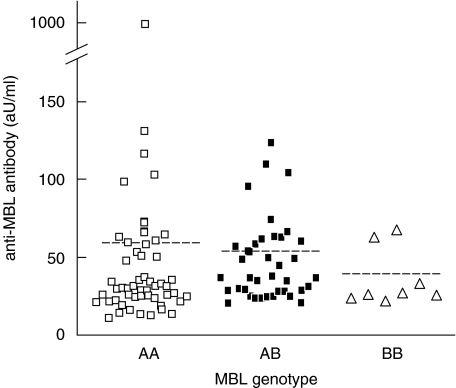

We next examined whether genotypes of the MBL gene in patients with SLE are associated with levels of anti-MBL antibodies (Fig. 4). Titres of anti-MBL antibodies tended to be lower in patients with allele B (AA; 60·15 ± 133·3, AB; 50·10 ± 26·95, BB; 38·23 ± 18·88), but no significant differences were observed.

Fig. 4.

Association between genotypes of the mannose-binding lectin (MBL) gene and levels of anti-MBL antibodies in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). AA; homozygosity for the codon 54 wild-type allele, AB; heterozygosity for the codon 54 variant, BB; homozygosity for the codon 54 variant allele. Dotted lines indicate average of titres of anti-MBL antibodies in each genotype. aU, arbitrary units.

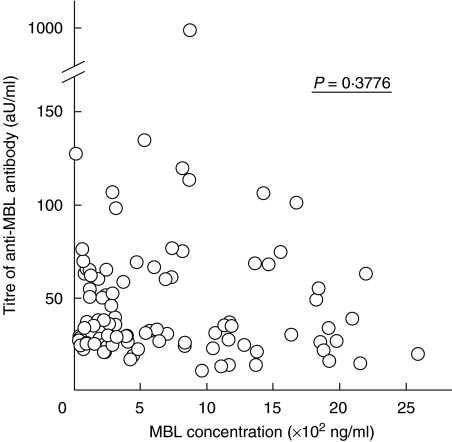

Finally, we compared the serum concentrations of MBL and titres of anti-MBL antibodies in patients with SLE. We found no significant relationship between them (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Association between titres of anti mannose-binding lectin (MBL) antibodies and concentrations of MBL in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) patients. P-value by Spearman's rank correlation test. aU, arbitrary units.

Relationships between the presence of anti-MBL antibodies in sera, and clinical characteristics or disease parameters of SLE

We investigated whether patients having anti-MBL antibodies at titres above 2 sd. of the average in healthy controls had some significant clinical characteristics (Table 1). No significant associations were observed. However, patients with higher serum concentration of anti-MBL antibodies tended to have a lower occurrence of anti-DNA antibodies, although statistical significance was not achieved. The incidence of infections requiring hospitalization during their course of SLE was not significantly higher in patients with higher serum concentration of anti-MBL antibodies.

Table 1.

Discase characteristics of 111 patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) categorized by positivity of anti-mannose-binding lectin (MBL) antibody

| Positive (n = 9) | Negative (n = 102) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Malar rash | 3 | 44 | 0·7309 |

| Discoid lupus | 0 | 13 | 0·5951 |

| Photosensitivity | 1 | 22 | 0·6821 |

| Oral ulcers | 2 | 20 | 0·9999 |

| Arthritis | 5 | 59 | 0·9999 |

| Serositis | 4 | 22 | 0·2099 |

| Renal disorder | 1 | 29 | 0·4399 |

| Neurological disorder | 0 | 9 | 0·9999 |

| Haematologic disorder | |||

| Haemolytic anemia | 0 | 8 | 0·9999 |

| leukopenia | 4 | 52 | 0·7422 |

| lymphopenia | 4 | 48 | 0·9999 |

| thrombocytopenia | 1 | 27 | 0·4447 |

| Anti-ds DNA Ab | 4 | 74 | 0·1225 |

| Anti-Sm Ab | 0 | 8 | 0·9999 |

| Antiphospholipid Ab | 3 | 18 | 0·3673 |

| ANA | 8 | 95 | 0·5033 |

| Infections requiring hospitalization | 3 | 29 | 0·7155 |

Anti-MBL antibody positive was defined as having a titre higher than mean +2 s.d. of 113 healthy individuals. Serositis, pleuritis or pericarditis; renal disorder, proteinuria or cellular casts; neurological disorder, seizures or psychosis; Anti-ds DNA Ab, anti-double strand DNA antibody; Anti-Sm Ab, anti-Sm antibody; Antiphospholipid Ab, antiphospholipid antibody. P= AA + AB versus BB by chi-square analysis.

We next analysed whether or not titres of anti-MBL antibodies are associated with various disease parameters of SLE in 111 SLE patients. Anti-DNA antibodies and total IgG tended to be positively related with anti-MBL antibodies, but statistical significance was not achieved. No other correlation was observed (Table 2).

Table 2.

Associations of titres of anti-mannose-binding lectin (MBL) antibody and various disease parameters of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) in 106 SLE patients

| Disease parameters of SLE | P-valuea |

|---|---|

| Anti-DNA antibody | 0·2173 |

| C3 | 0·8844 |

| C4 | 0·2131 |

| CH50 | 0·7919 |

| IgG | 0·0665 |

| IgA | 0·9026 |

| IgM | 0·1637 |

Spearman's rank correlation test.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we found the presence of autoantibodies against MBL in some patients with SLE. This is in accordance with the study by Seelen et al. [34], which was published very recently.

We confirmed that we were indeed detecting anti-MBL antibodies by; addition of EDTA in the enzyme immunoassay, thereby inhibiting the Ca2+ dependent binding of carbohydrate recognition domain on MBL to carbohydrates on IgG; digesting IgG with pepsin, and confirming that the binding region of IgG was on F(ab′)2; and detecting an inhibition of aqueous MBL to the binding of IgG to solid phase MBL. These methods and results are similar to those reported by Seelen et al. [34], except that we did detect dose dependent inhibition by our inhibition assay. The reason for this discrepancy is unclear, but may possibly be due to the nature of anti-MBL antibodies in individual patients, or concentrations or conformations of MBL used in the assays.

Similarities in structure and function exist between MBL and C1q, and it is known that C1q-deficient or anti-C1q antibody positive individuals have a high probability of developing SLE [5,30,35,36]. It has been reported that MBL deficiency may be associated with the occurrence of SLE [18–22], although deficiency of MBL is not an extremely high risk factor, in contrast to deficiencies of other complement molecules such as C1q. The presence of autoantibodies against MBL may cause similar pathological conditions to those found in MBL deficiency, as with the case of anti-C1q antibodies. In this context, it is noteworthy that a previous study has shown that anti-C1q antibodies do not recognize MBL [37], which suggests that anti-MBL and anti-C1q antibodies are not identical.

In accord to previous studies, serum MBL concentrations were closely associated with the MBL genotypes of the individuals studied (Fig. 3). However, in this study, no significant differences in serum MBL concentrations were observed between SLE patients and healthy controls, when individuals with the same genotype were compared. This is different from the study by Seelen et al. [34], where they found that serum MBL concentrations were higher in SLE patients than in controls. This difference may be due to differences in MBL genotype distributions or disease activities of SLE in the individuals studied, or other unknown factors.

We next asked whether there is any association between levels of anti-MBL antibodies and MBL genotypes. No such correlation was observed (Fig. 4). However, levels of anti-MBL antibodies in patients having genotype AB were higher than those in patients with genotype AA, if we excluded one patient with genotype AA with an extremely high level of anti-MBL antibodies (Fig. 4). In addition, some genotype BB patients had anti-MBL antibodies (Fig. 4). We went on to study the relationship between serum MBL concentration and levels of anti-MBL antibodies. There was no statistically significant relationship (Fig. 5). These findings support the notion that elevated serum MBL is not a causative factor for anti-MBL antibody production, and other factors should contribute to the production of these autoantibodies. One possible factor is the production of mutated MBL protein in genotype AB or BB individuals. Individuals with genotype AB or BB produce a mutated MBL protein which is degraded in sera, since they are unable to form a stable oligomerized structure [12,38]. These degraded MBL protein products may have a role in the occurrence of anti-MBL antibodies. However, at this point, this remains only a speculation. Other factors must be important as well, since some patients with genotype AA also have anti-MBL antibodies. Many questions need to be solved, before the mechanisms of autoantigen recognition and autoantibody production including anti-MBL antibodies could be clarified.

We examined the disease characteristics of SLE in anti-MBL antibodies positive patients (Table 1). There were no significant relationships between the possession of a significantly high titre of anti-MBL antibodies, and the characteristics or parameters of SLE. This is in accord with the report by Seelen et al. [34], which showed no difference between anti-MBL levels in sera of patients with active disease and inactive disease, especially concerning renal involvement. However, among patients having high titre of anti-MBL antibodies, smaller number of patients tended to have anti-DNA antibodies, and more patients (3 of 9 patients, 33%) developed intestinal pneumonitis, which usually occur in less than 10% of SLE patients [39]. Thus, we felt that some cases had somewhat atypical features of SLE. Whether this is only a coincidence or not is unclear. A study of larger number of patients should be done to clarify the clinical significance of anti-MBL antibodies in SLE.

It has been reported that individuals lacking MBL are prone to severe episodes of bacterial infections from early life [15–17]. A recent study has shown that presence of MBL minority alleles is a risk factor for infection in patients undergoing bone marrow transplantation [40]. It is also reported that the MBL deficiency, resulting from the possession of the variant alleles of the MBL gene, is a risk factor in patient receiving immunosuppressive therapy [19,20]. Although we anticipated that decreased MBL function caused by anti-MBL antibodies might lead to more frequent infections during the course of SLE, we could not find, in the present study, any significant associations between the presence of anti-MBL antibodies and the occurrence of infections requiring hospitalization after initiation of therapy of SLE. The effect of anti-MBL antibodies to increased susceptibility to infections in individuals under immunosuppressive therapy may not be as large as that caused by MBL gene polymorphisms. Since only 9 patients had significantly high titre of serum anti-MBL antibodies, a larger study is necessary to confirm this observation.

In conclusion, we detected anti-MBL antibodies in sera of patients with SLE. However, we could not find any significant relationships with MBL genotype, clinical characteristics and parameters of SLE in this study. Further studies are necessary to elucidate the actual functions of autoantibodies to MBL in the pathogenesis of SLE, and to determine the value of measuring these autoantibodies in clinical practice.

References

- 1.Winchester RJ, Nunez-Roldan A. Some genetic aspects of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1982;25:833–7. doi: 10.1002/art.1780250724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deapen D, Escalante A, Weinrib L, Horwitz D, Bachman B, Roy-Burman P, Walker A, Mack TM. A revised estimate of twin concordance in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1992;35:311–8. doi: 10.1002/art.1780350310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Atkinson JP. Complement deficiency: predisposing factor to autoimmune syndromes. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 1989;7:S95–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arnett FC, Reveille JD. Genetics of systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 1992;18:865–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bowness P, Davies KA, Norsworthy PJ, Athanassiou P, Taylor-Wiedeman J, Borysiewicz LK, Meyer PA, Walport MJ. Hereditary C1q deficiency and systemic lupus erythematosus. QJM. 1994;87:455–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Walport MJ. Complement deficiency and disease. Br J Rheumatol. 1993;32:269–73. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/32.4.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Korb LC, Ahearn JM. C1q binds directly and specifically to surface blebs of apoptotic human keratinocytes. complement deficiency and systemic lupus erythematosus revisited. J Immunol. 1997;158:4525–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mevorach D, Zhou JL, Song X, Elkon KB. Systemic exposure to irradiated apoptotic cells induces autoantibody production. J Exp Med. 1998;188:387–92. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.2.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holmskov U, Malhotra R, Sim RB, Jensenius JC. Collectins: collagenous C-type lectins of the innate immune defense system. Immunol Today. 1994;15:67–74. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(94)90136-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sastry K, Herman GA, Day L, Deignan E, Bruns G, Morton CC, Ezekowitz RA. The human mannose-binding protein gene. Exon structure reveals its evolutionary relationship to a human pulmonary surfactant gene and localization to chromosome 10. J Exp Med. 1989;170:1175–89. doi: 10.1084/jem.170.4.1175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Madsen HO, Garred P, Kurtzhals JA, Lamm LU, Ryder LP, Thiel S, Svejgaard A. A new frequent allele is the missing link in the structural polymorphism of the human mannan-binding protein. Immunogenetics. 1994;40:37–44. doi: 10.1007/BF00163962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sumiya M, Super M, Tabona P, Levinsky RJ, Arai T, Turner MW, Summerfield JA. Molecular basis of opsonic defect in immunodeficient children. Lancet. 1991;29:1569–70. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)93263-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Madsen HO, Garred P, Thiel S, Kurtzhals JA, Lamm LU, Ryder LP, Svejgaard A. Interplay between promoter and structural gene variants control basal serum level of mannan-binding protein. J Immunol. 1995;15:3013–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Madsen HO, Satz ML, Hogh B, Svejgaard A, Garred P. Different molecular events result in low protein levels of mannan-binding lectin in populations from southeast Africa and South America. J Immunol. 1998;161:3169–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koch A, Melbye M, Sorensen P, et al. Acute respiratory tract infections and mannose-binding lectin insufficiency during early childhood. JAMA. 2001;285:1316–21. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.10.1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Summerfield JA, Ryder S, Sumiya M, Thursz M, Gorchein A, Monteil MA, Turner MW. Mannose binding protein gene mutations associated with unusual and severe infections in adults. Lancet. 1995;345:886–9. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)90009-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Summerfield JA, Sumiya M, Levin M, Turner MW. Association of mutations in mannose binding protein gene with childhood infection in consecutive hospital series. Br Med J. 1997;314:1229–32. doi: 10.1136/bmj.314.7089.1229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davies EJ, Snowden N, Hillarby MC, Carthy D, Grennan DM, Thomson W, Ollier WE. Mannose-binding protein gene polymorphism in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38:110–4. doi: 10.1002/art.1780380117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garred P, Madsen HO, Halberg P, Petersen J, Kronborg G, Svejgaard A, Andersen V, Jacobsen S. Mannose-binding lectin polymorphisms and susceptibility to infection in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42:2145–52. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199910)42:10<2145::AID-ANR15>3.0.CO;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garred P, Voss A, Madsen HO, Junker P. Association of mannose-binding lectin gene variation with disease severity and infections in a population-based cohort of systemic lupus erythematosus patients. Genes Immun. 2001;2:442–50. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6363804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ip WK, Chan SY, Lau CS, Lau YL. Association of systemic lupus erythematosus with promoter polymorphisms of the mannose-binding lectin gene. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41:1663–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tsutsumi A, Sasaki K, Wakamiya N, et al. Mannose-binding lectin gene: polymorphisms in Japanese patients with systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis and Sjögren's syndrome. Genes Immun. 2001;2:99–104. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6363744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ogden CA. deCathelineau A, Hoffmann PR, Bratton D, Ghebrehiwet B, Fadok VA, Henson PM. C1q and mannose binding lectin engagement of cell surface calreticulin and CD91 initiates macropinocytosis and uptake of apoptotic cells. J Exp Med. 2001;194:781–95. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.6.781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.James JA, Kaufman KM, Farris AD, Taylor-Albert E, Lehman TJ, Harley JB. An increased prevalence of Epstein-Barr virus infection in young patients suggests a possible etiology for systemic lupus erythematosus. J Clin Invest. 1997;15(100):3019–26. doi: 10.1172/JCI119856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.James JA, Neas BR, Moser KL, Hall T, Bruner GR, Sestak AL, Harley JB. Systemic lupus erythematosus in adults is associated with previous Epstein-Barr virus exposure. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44:1122–6. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200105)44:5<1122::AID-ANR193>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Okada M, Ogasawara H, Kaneko H, et al. Role of DNA methylation in transcription of human endogenous retrovirus in the pathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 2002;29:1678–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hisano S, Matsushita M, Fujita T, Endo Y, Takebayashi S. Mesangial IgA2 deposits and lectin pathway-mediated complement activation in IgA glomerulonephritis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2001;38:1082–8. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2001.28611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lhotta K, Wurzner R, Konig P. Glomerular deposition of mannose-binding lectin in human glomerulonephritis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1999;14:881–6. doi: 10.1093/ndt/14.4.881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Steinfeld S, Penaloza A, Ribai P, et al. d-mannose and N-acetylglucosamine moieties and their respective binding sites in salivary glands of Sjögren's syndrome. J Rheumatol. 1999;26:833–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Siegert C, Daha M, Westedt ML, van der Voort E, Breedveld F. IgG autoantibodies against C1q are correlated with nephritis, hypocomplementemia, and dsDNA antibodies in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 1991;18:230–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ohtani K, Suzuki Y, Eda S, et al. High-level and effective production of human mannan-binding lectin (MBL) in Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells. J Immunol Meth. 1999;222:135–44. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(98)00190-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hakozaki Y, Yoshiba M, Sekiyama K, et al. Mannose-binding lectin and the prognosis of fulminant hepatic failure caused by HBV infection. Liver. 2002;22:29–34. doi: 10.1046/j.0106-9543.2001.01516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sasaki K, Tsutsumi A, Wakamiya N, Ohtani K, Suzuki Y, Watanabe Y, Nakayama N, Koike T. Mannose-binding lectin polymorphisms in patients with hepatitis C virus infection. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2000;35:960–5. doi: 10.1080/003655200750023039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Seelen MA, Trouw LA, van der Hoorn JW, Fallaux-van den Houten FC, Huizinga TW, Daha MR, Roos A. Autoantibodies against mannose-binding lectin in systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Exp Immunol. 2003;134:335–43. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2003.02274.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Slingsby JH, Norsworthy P, Pearce G, Vaishnaw AK, Issler H, Morley BJ, Walport MJ. Homozygous hereditary C1q deficiency and systemic lupus erythematosus. A new family and the molecular basis of C1q deficiency in three families. Arthritis Rheum. 1996;39:663–70. doi: 10.1002/art.1780390419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Walport MJ, Davies KA, Botto M. C1q and systemic lupus erythematosus. Immunobiology. 1998;199:265–85. doi: 10.1016/S0171-2985(98)80032-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martensson U, Thiel S, Jensenius JC, Sjoholm AG. Human autoantibodies against Clq: lack of cross reactivity with the collectins mannan-binding protein, lung surfactant protein A and bovine conglutinin. Scand J Immunol. 1996;43:314–20. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.1996.d01-48.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Garred P, Larsen F, Madsen HO, Koch C. Mannose-binding lectin deficiency – revisited. Mol Immunol. 2003;40:73–84. doi: 10.1016/s0161-5890(03)00104-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Eisenberg H, Dubois EL, Sherwin RP, Balchum OJ. Diffuse interstitial lung disease in systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann Intern Med. 1973;79:37–45. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-79-1-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rocha V, Franco RF, Porcher R, et al. Host defense and inflammatory gene polymorphisms are associated with outcomes after HLA-identical sibling bone marrow transplantation. Blood. 2002;100:3908–18. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-04-1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]