Abstract

Intramuscular injection with plasmid DNA encoding the human thyrotropin receptor (TSHR) has been known to elicit symptoms of Graves’ disease (GD) in outbred but not inbred mice. In this study, we have examined, firstly, whether intradermal (i.d.) injection of TSHR DNA can induce hyperthyroidism in BALB/c mice and, secondly, whether coinjection of TSHR- and cytokine-producing plasmids can influence the outcome of disease. Animals were i.d. challenged at 0, 3 and 6 weeks with TSHR DNA and the immune response was assessed at the end of the 8th or 10th week. In two experiments, a total of 10 (67%) of 15 mice developed TSHR-specific antibodies as assessed by flow cytometry. Of these, 4 (27%) mice had elevated thyroxine (TT4) levels and goitrous thyroids with activated follicular epithelial cells but no evidence of lymphocytic infiltration. At 10 weeks, thyroid-stimulating antibodies (TSAb) were detected in two out of the four hyperthyroid animals. Interestingly, in mice that received a coinjection of TSHR- and IL-2- or IL-4-producing plasmids, there was no production of TSAbs and no evidence of hyperthyroidism. On the other hand, coinjection of DNA plasmids encoding TSHR and IL-12 did not significantly enhance GD development since two out of seven animals became thyrotoxic, but had no goitre. These results demonstrate that i.d. delivery of human TSHR DNA can break tolerance and elicit GD in inbred mice. The data do not support the notion that TSAb production is Th2-dependent in murine GD but they also suggest that codelivery of TSHR and Th1-promoting IL-12 genes may not be sufficient to enhance disease incidence and/or severity in this model.

Keywords: murine Graves’ disease, genetic immunization, intradermal, thyrotropin receptor, thyroid

INTRODUCTION

The thyrotropin (or thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH)) regulates functional and proliferative responses of thyroid follicular cells via binding to its receptor (TSHR) and triggering several signal transduction pathways. TSHR is a G-protein-coupled receptor that consists of 764 amino acids including a 21 aa signal peptide [1]. It has a large N-terminal extracellular domain (ECD) that confers TSH-binding specificity and a C-terminal half with the characteristic seven membrane-spanning regions and a cytoplasmic tail. In Graves’ disease (GD), autoantibodies to TSHR continually stimulate thyrocytes to produce and secrete thyroid hormones, leading to hyperthyroidism. It is well established, however, that sera from GD patients frequently contain not only thyroid-stimulating antibodies (TSAbs) that mimic TSH, but also TSHR-blocking antibodies (TBAbs) that act antagonistically to TSAbs by inhibiting TSH-induced stimulation. The relative serum concentrations of these autoantibodies determine the clinical outcome and persistent hyperthyroidism is evident when TSAbs predominate [2].

In recent years, faced with the lack of animal models that spontaneously develop GD, investigators have focused their efforts in inducing experimental GD via deliberate immunizations of animals with TSHR. (reviewed in [3]). The main objective has been to reproduce the salient features of GD, i.e. preferential formation of TSAbs associated with hormonal evidence for hyperthyroidism (elevated thyroxine and/or reduced thyrotropin levels) and histological evidence for activation of thyroid follicular cells. Accompanying common features of GD such as goitre formation, lymphocytic infiltration of the thyroid, weight loss, orbital changes indicative of thyroid eye disease, etc. have been also monitored as corroborative evidence. The very low expression of TSHR on thyrocytes was initially a major obstacle in producing large quantities of purified TSHR required for immunizations. Nevertheless, challenges of animals with thyroid cell line-derived receptor [4], recombinant TSHR ECD preparations from prokaryotic [5–7], or eukaryotic [8–11] cells, or TSHR peptides (reviewed in [3]) were either unsuccessful in establishing a GD model or provided evidence for induction of TSAbs and/or elevated thyroxine levels that has not been independently confirmed. In these studies, TSHR-specific antibodies were almost invariably detected but lymphocytic thyroiditis was only occasionally observed [4,5,8]. Lack of appropriate folding of the purified receptor, i.e. its inability to maintain a conformation able to bind TSH, was proposed as a preventing factor for the induction of TSAbs.

To circumvent this obstacle, Shimojo et al. [12] applied a novel immunization protocol based on multiple i.p. challenges of AKR/N mice with murine fibroblasts doubly transfected with cDNAs encoding a murine MHC class II molecule and the full length, functional human TSHR. About 20% of the immunized mice had elevated thyroxine levels, TSAbs, and goitre formation with histological signs of thyrocyte activation. These promising results were independently confirmed [13–15] and extended with the use of TSHR-transfected lymphoblastoid B cells, expressing both MHC class II and B-7 molecules, that elicited TSAbs and hyperthyroidism in almost 100% of immunized BALB/c mice [16]. This methodology, however, was limited by its reliance on antigen-presenting cell (APC) lines that were available for only certain strains of mice. Intramuscular (i.m) administration of plasmids containing the human TSHR cDNA was described by Costagliola et al. [17] as an alternative promising strategy, as it induced GD in 20% of outbred NMRI, but not inbred BALB/c, mice [18]. Recently, successful induction of GD in mice was reported following multiple i.m. injections of recombinant adenovirus vector expressing the TSHR [19]. However, despite the considerable progress, the optimal immunization conditions for induction of TSAbs in mice, challenged either with plasmid DNA or adenovirus vectors, remain poorly understood. In particular, the role of different helper cell types (Th1 versus Th2) and antibody isotypes in the formation of TSAbs is under considerable debate [20,21].

In this report, we have examined whether intradermal (i.d.) delivery of a DNA plasmid encoding the human TSHR can elicit GD in BALB/c mice. The skin is an ideal anatomical site for immunizations since it is rich in dendritic cells (Langerhans’ cells) that normally take up exogenous antigens. Our study was based on prior findings that i.d. challenge of mice with plasmid DNA encoding viral antigens can elicit significant specific B- and T-cell responses [22,23]. We have also investigated whether the DNA dose or the codelivery of DNA plasmids producing IL-2, IL-4 or IL-12 genes might influence the outcome of the response.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmid preparation

Human TSHR cDNA from the pCI-neo vector [13,24] was excised using XhoI and NotI and subcloned into the pcDNA3·1zeo+ mammalian expression vector (InVitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) (pcDNA3-TSHR). The subcloned human TSHR gene was sequenced and was found to be identical to a published sequence [25] with the exception of two nucleotide substitutions at positions 1477 (G→A) and 1801 (C→T); the latter caused an amino acid substitution at position 601 (H→Y), as has been reported in previous studies [26–28], possibly reflecting a polymorphism. The murine IL-2 gene was amplified from the pcDV1 vector (ATCC) using the primers IL-2-F = CGGGTAC CATGTACAGCATGCAG and IL-2-R = CCTCTAGATTATT GAGGGCTTGTTG and inserted (via KpnI and XbaI) into the multicloning site of pcDNA3·1zeo+(pcDNA3-IL-2). Similarly, the murine IL-4 gene was amplified fromthepGCVII/IL-4plasmid [29] (a kind gift from Dr B. H. Barber) with the amplimers IL-4-F = GCGGTACCATGGGTCTCAACCCC and IL-4-R = CGTCTAGACTACGAGTAATCCATTTGC and ligated into the multicloning site (via KpnI and XbaI) of pcDNA3·1zeo+ (pcDNA3-IL-4). The DNA sequences of the subcloned mIL-2 and IL-4 genes are in complete agreement with the published sequences [30,31]. The pGCVII.IL-12 plasmid, also provided by Dr B. H. Barber, has been previously characterized [29]. Transformation of XL1-Blue E.coli cells, rendered competent by calcium chloride, was performed using a standard protocol (Technical Bulletin no. 95, Promega, Madison, WI, USA). All plasmids used for DNA immunizations were purified using EndoFree™ Plasmid Giga Kits (Qiagen, Mississauga, ON, Canada). The DNA pellets were dissolved in sterile 0·9% NaCl pyrogen-free solution and stored at −20°C.

Testing expression and functionality of cloned cytokine genes

Plasmids containing the murine IL-2 and IL-4 genes were used to transiently transfect CHO-K1 cells (ATCC; CCL-61) using the Transfast Transfection Reagent (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). Serial dilutions of supernatants were tested for the presence of cytokines using sandwich ELISA assays [32] or bioassays based on the proliferation of the IL-2 and IL-4-dependent cell lines CTLL-2 and CT.4S, respectively [33]. To test for the expression of functional IL-12, a bioassay based on the ability of IL-12 to induce IFN-γ production in resting mouse splenocytes was used [34]. Briefly, CHO-K1 cells were transfected with pGCV-IL-12 and the supernatants were harvested 5 days later. Then, in 24-well plates, 1 × 107 mouse splenocytes/ml/well were cultured in a 1 : 2 dilution of these supernatants with the addition of 50 U rIL-2/ml. After a 48 h incubation, the supernatants were tested for the presence of IFN-γ by sandwich ELISA as previously described [32].

cAMP assay for functional TSHR expression

CHO-K1 cells transiently transfected with either pcDNA3 (control) or pcDNA3 -TSHR were harvested following a 48 h transfection period, washed, and resuspended in Ham's F12 media supplemented with 0·1% BSA and 0·2 mg/ml 3-isobutyl-1-methyl-xanthine (Sigma) (termed F12 complete medium). CHO cells stably expressing native human TSHR (JP09 cells) [35] were used as positive controls. In flat-bottomed 96-well plates, duplicate samples of 4 × 104 cells per well were incubated in the presence or absence of 5 mU/ml of bovine TSH (Sigma) for 2 h at 37°C and 5% CO2. Subsequently, the intracellular cAMP was extracted with cell lysis reagent from a commercial kit (Biotrak cAMP competitive EIA kit, Amersham Pharmacia Biotech Inc., Uppsala, Sweden), and measured according to the manufacturer's protocol. Results are expressed as pmol cAMP/ml.

Mice and immunization schedules

Female, 8–12 week old BALB/cJ mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME, USA). Intradermal (i.d.) injections of plasmid DNA, at 1 µg/µl saline, were delivered to one or five sites (10 µl per site) of the shaved posterior-dorsal skin of kentamine/xylazine-anaesthetized mice, with a 1-ml syringe and a 30-gauge needle. Boosting was performed in the same manner at 3 and 6 weeks postpriming. Blood samples were obtained from retro-bulbar sinus at various time points and sera were tested individually in all assays. All animal experimentation protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care Committee of Memorial University of Newfoundland and were in accord with accepted standards on humane animal care. Mice were housed under conventional (non SPF) conditions.

Detection of TSHR-specific antibodies in immune sera

The binding of antibodies to native TSHR was measured by flow cytometry using GPI cells, i.e. CHO cells expressing the TSHR ECD anchored via a glycophosphatidylinositol (GPI) link [36]. CHO1 cells transfected with ‘empty’ pcDNA3 vector were used as specificity controls. GPI or CHO1 cells were grown to 70–90% confluence, washed twice with PBS, detached from the culture flasks with nonenzymatic cell dissociation solution (Sigma) and transferred into wells of 96 V-bottom well plates (2 × 105 cells/well). Cells were centrifuged at 500 × g for 2 min at 4°C, washed once in PBS containing 1% BSA and 0·1% NaN3 (FACS buffer) and then incubated on ice for 30 min with 1 : 5 diluted mouse serum in 50 µl of FACS buffer. The purified mAbs A10 (IgG2b), known to recognize TSHR amino acids 22–35 [37], and HB65 (IgG2a) specific for the nucleoprotein of influenza type A viruses [38] were used as positive and negative controls (at 10 µg/ml). Cells were washed 4× with 150 µl of FACS buffer and incubated with 50 µl of FITC-conjugated, Fc-specific goat anti-mouse IgG (Sigma) diluted 1 : 80 in FACS buffer, on ice, in the dark for 30 min. Cells were washed again 4× with FACS buffer, suspended in 500 µl PBS containing 1% paraformaldehyde (Sigma) and transferred to Falcon tubes. The fluorescence of 10 000 cells/tube was assayed by a FACStar Plus analyser (Becton-Dickinson Inc., Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). Results are expressed as the mean channel fluorescence (MCF) ratio between GPI and CHO1 cells. Detection of thyroid-stimulating antibodies (TSAb) was performed by the cAMP assay as described above. Briefly, 4 × 104JP09 cells [35]per well were plated in 96-well flat-bottomed plates and cultured for 24 h in growth medium. Before the assay, the medium was aspirated and immune sera diluted 1 : 10 in Ham's F12 complete medium (90 µl/well) were added in duplicate wells and incubated for 2 h at 37°C. The intracellular cAMP was extracted and measured by the Biotrak kit according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Total T4 determination

A radioimmunoassay (RIA) kit (DYNOtest; BRAHMS Diagnostica GmbH, Berlin, Germany) was used for TT4 determination in mouse sera. A standard curve was constructed with reference standards provided by the manufacturer; TT4 values are expressed in µg/dl.

Histology

For assessment of mononuclear infiltration, thyroids were fixed in formalin, embedded in methacrylate, and 4-µm step sections were stained with haematoxylin and eosin for microscopic examination.

RESULTS

Functional expression of cytokine and TSHR genes

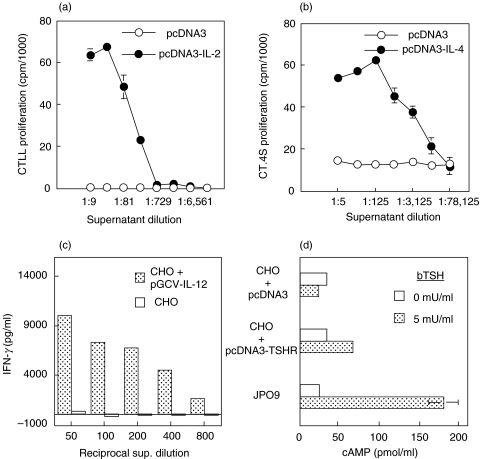

Prior to their use in vivo, all plasmids were tested for their capacity to functionally express their cDNA following transfection of CHO cells. As shown in Fig. 1a,b, the supernatants of cells transfected with pcDNA3 plasmids carrying the IL-2 or IL4 genes could drive the proliferation of the IL-2-dependent CTLL line and IL-4-dependent CT.4S line, respectively, in a dose-dependent fashion. Supernatants from cells transfected with the ‘empty’ pcDNA3 vector were devoid of cytokine activity. The IL-2 and IL-4 content of supernatants was also confirmed by ELISA (not shown). To test for the expression of functional IL-12, the pGCV-IL-12 construct was transfected into CHO cells, and two days later, supernatants from these cultures were tested for their ability to induce IFN-γ production in resting mouse splenocytes. As indicated in Fig. 1c, significant amounts of IFN-γ were detected in splenocyte cultures following incubation with supernatants from pGCV-IL-12-transfected, but not untransfected, CHO cells. Lastly, the functional expression of the TSHR gene was monitored by the capacity of bTSH to bind on transfected CHO cells and induce cAMP production. Only cells transfected with the pcDNA3-TSHR – not with pcDNA3 alone – contained significant amounts of cAMP following stimulation with bTSH (Fig. 1d). JPO9 cells which stably express TSHR (positive controls) contained the highest amount of cAMP following activation.

Fig. 1.

Proliferation of IL-2-dependent (a) or IL-4-dependent (b) cell lines in the presence of culture supernatants from CHO cells transiently transfected with the plasmids shown. Results depict incorporation of 3[H]-thymidine and are expressed as cpm means of triplicate wells ± SD. (c) IL-12-induced IFN-γ production in mouse splenocytes cultured with supernatants of CHO cells transiently transfected with pGCV-IL-12. Quantification of IFN-γ was done by sandwich ELISA. (d) Assay for functional expression of TSHR in CHO cells transiently transfected with the indicated plasmid vectors. JPO9 cells stably expressing TSHR were used as controls. Cells were cultured with or without bTSH for 2 h, lysed, and total cellular cAMP was assayed in cell lysates using a commercial kit. Results are expressed as means of duplicate values ± SD.

Induction of TSHR-specific IgG Abs following i.d. challenge of mice with TSHR cDNA

The immunogenicity of the pcDNA3-TSHR plasmid was first examined by challenging two groups of BALB/c mice (8 mice per group) with 10 and 50 µg plasmid DNA delivered by i.d. injections at one or five sites on the dorsal skin, respectively. The same dose and route of antigen administration was used in booster injections at 3 and 6 weeks after the initial challenge. Control mice were similarly immunized with equivalent doses of ‘empty’ pcDNA3 vector. Detection of TSHR-specific IgG antibodies in immune sera was performed by flow cytometry at 8 and 10 weeks after the initial priming, by examining their relative binding (MCF ratio) on TSHR-positive GPI cells vs. CHO1 cells that do not express TSHR. As in previous studies [13], it was established that none of the control sera showed specific binding on GPI cells (data not shown). MCF ratio values that were higher than the mean + 3 SD of the control groups were considered positive. As shown in Table 1, four of eight mice (nos. 5, 6, 7 and 8) that were challenged 3× with 10 µg of pcDNA3-TSHR mounted a TSHR-specific IgG response at the 8- and 10 week intervals. In particular, the immune sera of two mice (nos. 5 and 8) were strongly positive with MCF ratios varying from 30·8 to 85·7 at week 8, from 18·5 to 69·5 at week 10, i.e. they exhibited a 12–48-fold increase as compared to control MCF ratios. Similarly, five of eight mice (nos. 1, 2, 3, 6 and 7) that were immunized 3× with 50 µg of pcDNA3-TSHR developed strong TSHR-specific responses with GPI/CHO1 MCF ratios ranging from 6·4 to 38·6 at week 8, to 21 to 56·6 at week 10. These data demonstrated that i.d. delivery of 10 or 50 µg TSHR cDNA was efficacious in inducing strong specific IgG responses in a large number of immunized animals.

Table 1.

Production of TSHR-specific Abs and thyroid function in BALB/c mice following i.d. immunization with plasmid DNA carrying the human TSHR gene

| GPI/CHO1 MCF ratio† | cAMP (pmol/ml)‡ | TT4 (µg/dl) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antigen* (dose) | Mouse No. | Week 8 | Week 10 | Week 8 | Week 10 | Week 8 | Week 10 |

| pcDNA3 | 1 | 1·7 | 1·4 | 18·5 | 27·4 | 4·8 | 5·7 |

| (10 µg) | 2 | 1·6 | 1·4 | 17·5 | 21·8 | 5·4 | 5·3 |

| 3 | 1·6 | 1·4 | 21·5 | 20·1 | 6·1 | 5·8 | |

| 4 | 1·5 | 1·3 | 19·0 | 22·5 | 5·2 | 6·1 | |

| 5 | 1·4 | 1·4 | 17·9 | 21·7 | 5·0 | 5·3 | |

| Mean + 3 SD | 1·8 | 1·5 | 24·5 | 31·3 | 7·3 | 7·3 | |

| pcDNA3-TSHR | 1 | 1·5 | 1·4 | 21·2 | 18·9 | 6·8 | 6·6 |

| (10 µg) | 2 | 1·7 | 1·4 | 22·6 | 27·2 | 5·2 | 6·5 |

| 3 | 1·5 | 1·4 | 24·2 | 26·7 | 6·3 | 6·2 | |

| 4 | 1·7 | 1·5 | 20·0 | 21·8 | 6·4 | 6·4 | |

| 5 | 30·8 | 18·5 | 18·2 | 21·1 | 5·0 | 5·9 | |

| 6 | 7·7 | 7·6 | 16·9 | 24·3 | 5·2 | 6·2 | |

| 7 | 2·1 | 1·9 | 17·3 | 23·6 | 4·5 | 6·1 | |

| 8 | 85·7 | 69·5 | 19·5 | 29·0 | 5·8 | 6·1 | |

| pcDNA3 | 1 | 1·6 | 1·6 | 17·7 | 18·9 | 4·9 | 5·2 |

| (50 µg) | 2 | 1·5 | 1·4 | 19·2 | 23·7 | 6·0 | 5·9 |

| 3 | 1·5 | 1·4 | 21·6 | 21·7 | 5·2 | 6·5 | |

| 4 | 1·5 | 1·3 | 22·2 | 21·9 | 6·1 | 6·5 | |

| 5 | 2·8 | 2·0 | 22·5 | 23·8 | 5·0 | 6·5 | |

| 6 | 1·5 | 1·4 | 31·0 | 28·6 | 4·7 | 5·4 | |

| Mean + 3 SD | 3·4 | 2·2 | 36·2 | 32·8 | 7·1 | 7·7 | |

| pcDNA3-TSHR | 1 | 6·5 | 21·0 | 20·6 | 49·5 | 5·4 | 5·5 |

| (50 µg) | 2 | 6·4 | 26·3 | 24·7 | 34·5 | 13·5 | 13·4 |

| 3 | 11·0 | 56·6 | 17·5 | 30·8 | 6·4 | 6·1 | |

| 4 | 1·5 | 1·7 | 18·3 | 25·7 | 6·1 | 5·3 | |

| 5 | 1·1 | 1·3 | 20·3 | 24·2 | 6·0 | 5·6 | |

| 6 | 38·6 | D | 27·5 | D | 9·8 | D | |

| 7 | 10·2 | 30·7 | 34·8 | 22·1 | 7·7 | 16·2 | |

| 8 | 1·6 | 2·0 | 30·5 | 30·5 | 5·1 | 5·1 | |

All mice were primed i.d. with the indicated plasmid and dose and boosted with the same amount of DNA 3 and 6 weeks postpriming, as described in Materials and Methods.

TSHR-specific antibodies in 8 week and 10 week immune sera were detected by flow cytometry as described in Materials and Methods. Results are expressed as the MCF ratio between GPI and CHO1 cells.

JPO9 cells were stimulated with immune sera (diluted 1 : 10) for 2 h, and total cAMP was extracted and measured, as described in Materials and Methods.‡ Values greater than the control mean + 3 SD were considered positive and are represented in bold; ND, not determined.

Induction of hyperthyroidism and goitre following i.d. challenge of mice with TSHR cDNA

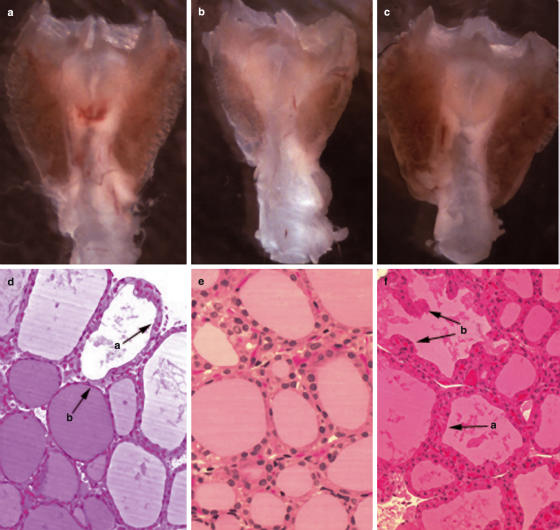

We subsequently examined the induction of TSAbs by monitoring the generation of intracellular cAMP in JPO9 cells incubated with immune or control sera. Thyroid function was assessed via the measurement of serum TT4. None of the mice immunized 3× with 10 µg pcDNA3-TSHR had detectable TSAb activity or significantly elevated TT4 values in the serum, as compared to control plasmid –injected mice (Table 1). In contrast, three mice (nos. 2, 6 and 7) from the group that received 3× the 50 µg pcDNA3-TSHR dose, presented with significantly elevated TT4 levels (7·7–13·5 µg/dl) at 8 weeks as compared to the control values (4·8–6·1 µg/dl). High TT4 levels persisted for 10 weeks in mice no. 2 (13·4 µg/dl) and no. 7 (16·2 µg/dl). (Mouse no.6 was lost during anaesthesia at 8 weeks). The hormonal data of mice nos. 2 and 7, however, did not correlate with the presence of serum TSAbs since only the week 10 serum from mouse no. 2 induced significant cAMP release in JPO9 cells. (Table 1). Also, one mouse serum (no.1) showed TSAb activity after 10 weeks of challenge but this did not correlate with enhanced TT4 levels in the same sample. The thyroids of the thyrotoxic mice no. 2 and 7 were goitrous (Fig. 2a,c) and contained follicles with epithelial hypertrophy and hypercellularity with occasional protrusions of the epithelium into the follicular lumen (Figs 2d,f). The thyroid of mouse no. 2 exhibited histological heterogeneity since follicles with thickened active epithelium were frequently seen next to follicles with flat, inactive thyrocytes filled with colloid (Fig. 2d). In contrast, the thyroid of mouse no. 7 had all follicles in an activation state (Fig. 2f). Intrathyroidal mononuclear cell infiltration was not detected in any of the mice of Table 1. These results provided direct evidence that i.d. delivery of naked DNA encoding TSHR can induce hyperthyroidism in mice.

Fig. 2.

Goitrous thyroids from thyrotoxic mice no.2 (a) or no.7 (c), i.d. challenged 3× with 50 µg of pcDNA3-TSHR, as described in Table 1. A normal thyroid is shown in (b). (d) Follicular heterogeneity in the thyroid of mouse no.2. A follicle with activated epithelial cells (a) is juxtaposed against a follicle with flat (inactive) epithelium (b). (e) Histological appearance of normal follicles. (f) Section of thyroid from mouse no.7, showing homogeneous distribution of hyperplastic follicles lined with activated thyrocytes (a) that frequently protrude into the follicular lumen (b). (d,e,f, × 200).

Codelivery of TSHR and cytokine genes as a means of biasing the immune response

In an effort to modulate the immune response to genetic immunization, we proceeded to i.d. challenge mice with coinjection of plasmids carrying the TSHR and cytokine genes. Control mice were challenged 3× with 50 µg of ‘empty’ vector plus 50 µg of either pcDNA3-IL-2 or pcDNA3-IL-4 to ensure that the cytokine-producing plasmids on their own, do not influence the background response. Indeed, the GPI/CHO1 MCF ratios, and cAMP and TT4 values of control sera remained at the same previous levels (Table 2). Interestingly, i.d. codelivery of TSHR DNA with pcDNA3-IL-2 did not enhance the Ab response since only one mouse (no. 5) out of eight mounted a marginal TSHR-specific response after 8 weeks (MCF ratio = 1·9). Also, no mice showed TSAb activity or elevated TT4 in their sera (Table 2). Similarly, codelivery of TSHR and IL-4-producing plasmids induced a slight increase in the MCF ratio values in 3 out of 7 mice after 8 weeks (MCF = 1·8) and in 3 out of 7 mice after 10 weeks (MCF = 2·2–3·2). There was no production of TSAbs and no evidence of hyperthyroidism in the animals of this group (Table 2).

Table 2.

Production of TSHR-specific Abs and thyroid function in BALB/c mice following i.d. coinjection of DNA plasmids carrying the human TSHR and the murine IL-2 or IL-4 cytokine genes

| GPI/CHO1 MCF ratio† | cAMP (pmol/ml)‡ | TT4 (µg/dl) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antigen* (dose) | Mouse no. | Week 8 | Week 10 | Week 8 | Week 10 | Week 8 | Week 10 |

| Controls (n = 8)† Mean + 3 SD | 1·3 | 1·5 | 26·8 | 32·4 | 7·2 | 6·9 | |

| pcDNA3-TSHR (50 µg) + pcDNA3-IL-2 (50 µg) | |||||||

| 1 | 1·1 | 1·1 | 24·3 | 32·3 | 5·7 | 6·5 | |

| 2 | 1·3 | 1·4 | 22·4 | 22·7 | 6·7 | 6·6 | |

| 3 | 1·3 | 1·3 | 17·3 | 24·0 | 7·0 | 6·1 | |

| 4 | 1·2 | 1·2 | 18·1 | 20·4 | 5·6 | 5·6 | |

| 5 | 1·9 | 1·3 | 20·3 | 16·1 | 6·8 | 5·9 | |

| 6 | 1·2 | 1·0 | 18·2 | 16·8 | 6·4 | 5·6 | |

| 7 | 1·2 | 1·1 | 16·7 | 18·5 | 6·2 | 6·1 | |

| 8 | 1·1 | 1·1 | 22·9 | 22·9 | 6·0 | 6·0 | |

| Controls (n = 7) ‡ Mean + 3 SD | 1·7 | 2·0 | 35·2 | 42·4 | 6·9 | 7·2 | |

| pcDNA3-TSHR (50 µg)+ pcDNA3-IL-4 (50 µg) | |||||||

| 1 | 1·8 | 1·3 | 30·7 | 32·7 | 5·5 | 5·4 | |

| 2 | 1·3 | 1·8 | 28·1 | 36·1 | 4·4 | 4·5 | |

| 3 | 1·8 | 2·2 | 23·5 | 27·7 | 5·6 | 4·7 | |

| 4 | 1·4 | 2·2 | 24·5 | 23·8 | 6·2 | 5·7 | |

| 5 | 1·5 | 1·9 | 25·3 | 22·6 | 5·5 | 5·8 | |

| 6 | 1·8 | 1·6 | 26·4 | 22·1 | 5·5 | 5·3 | |

| 7 | 1·7 | 3·2 | 31·3 | 20·3 | 6·3 | 6·5 | |

Immunizations and assays were performed as described in the legend to Table 1 and the Materials and Methods. Values greater than the control mean + 3 SD are considered positive and are represented in bold; ND, not determined.

Control mice were immunized with 50 µg pcDNA3 + 50 µg pcDNA-IL-2

Control mice were immunized with 50 µg pcDNA3 + 50 µg pcDNA-IL-4

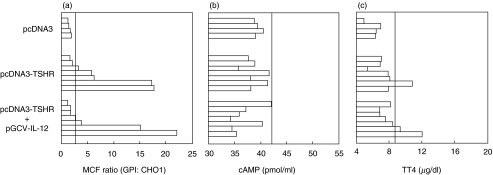

To investigate whether the immune response would be enhanced by the Th1-promoting cytokine IL-12, an additional experiment was performed in which three groups of mice received at 0, 3, and 6 weeks, i.d. injections of 50 µg empty pcDNA3 vector (n = 4), 50 µg pcDNA3-TSHR (n = 7), or codelivery of 50 µg TSHR DNA plus 10 µg of the pGCV-IL-12 plasmid (n = 7). It was observed (Fig. 3a) that five out of seven mice (nos. 3–7) challenged with TSHR cDNA developed, as previously, significant TSHR-specific IgG responses with two of these mice (nos. 6 and 7) showing large MCF ratios (>17). Mouse no. 6, was also hyperthyroid (Fig. 3c) (TT4 = 10·8 µg/dl, control range: 4·8–6·23 µg/dl) and had a goitrous gland exhibiting homogeneous distribution of follicles with activated epithelium, similar to that of Figs 2c,f. Co-administration of the IL-12-producing plasmid, however, did not significantly alter the incidence or severity of hyperthyroidism. Three of seven mice developed TSHR-specific Abs and two of those (nos. 6, and 7) exhibited large MCF ratios (>15) (Fig. 3a) and significant TT4 values (>9 µg/dl) (Fig. 3c) but no detectable goitre. In hyperthyroid mice, the TSAb values obtained via the cAMP assay (Fig. 3b) did not correlate with the hormonal data.

Fig. 3.

Assays for TSHR-specific antibodies (a), TSAbs (b) and TT4 (c) in sera of BALB/c mice i.d. challenged at 0, 3, and 6 weeks with the plasmids shown. The assays were performed 8 weeks after the initial priming. Bars depict individual mice. Responses are considered significant if they exceed the mean + 3 SD of the control values (pcDNA3 challenge only), indicated by the vertical lines.

DISCUSSION

In this report, we have shown that i.d. administration of plasmid DNA encoding the human TSHR can lead to induction of the salient features of GD in mice. Our study was prompted by prior evidence demonstrating that i.d. injections of DNA vaccines encoding influenza nucleoprotein elicit humoral and cellular responses [23]. After injection into the skin, keratinocytes and Langerhans cells are the major cell types transfected by plasmid DNA [23,29] and we hypothesize that TSAb-secreting B cells would recognize TSHR on such cells. According to current theory [39,40], helper signals would be delivered by CD4+ cells that recognize TSHR peptides on the surface of MHC class II positive Langerhans cells. Peptide-MHC complexes would be formed after processing of TSHR regurgitated by the same APC or taken up from other APC or somatic cells (cross-priming) via endocytosis of secreted protein or phagocytosis of apoptotic bodies [39]. B-cell activation would occur in draining lymph nodes where Langerhans cells would migrate possibly during the first 24 h after transfection, whereas non migratory keratinocytes might act in the longer term as a reservoir for continued production of antigen [39,41].

Immunization with TSHR cDNA via the i.m. route was reported to induce hyperthyroidism in outbred NMRI [17] but not inbred BALB/c mice [18] and genetic resistance of the BALB/c background was proposed as a possible reason for this discrepancy. Our results do not support this interpretation as they clearly show that genetic immunization with TSHR elicits the salient features of GD in this strain. In addition, thyrotoxicosis has been recently induced in BALB/c mice with other methodologies: after i.p. inoculation with TSHR-expressing lymphoblastoid B cells [16], i.m. challenge with adenovirus expressing TSHR [19] or s.c. delivery of adenovirus- infected dendritic cells expressing the receptor [42]. Thus, it is likely that experimental or environmental parameters rather than genetic factors may account for the lack of TSAbs and hyperthyroidism in BALB/c mice vaccinated i.m. with TSHR DNA in earlier [18] and more recent studies [13,20]. In this report, the overall incidence of hyperthyroidism among mice challenged with pcDNA3-TSHR has been 27% (4/15 mice) at 8 week (Table 1 and Fig. 3) ranging from 38% (Table 1) to 14% (Fig. 3), whereas it has varied from 0 to 100% in the above studies [13,16,18,19,20,42]. To what extent environmental factors can influence the incidence of murine GD is unknown, but it is worth noting that GD can be elicited by genetic immunization in mice housed in conventional facilities (this report and [17]) as well as in mice kept under specific-pathogen-free conditions, following challenge with TSHR-expressing adenovirus [19]. Ultimately, variable disease incidence is likely to reflect relative inadequacies of diverse protocols to meet two common goals: to express optimally the native TSHR on a cell surface for engagement of TSAb-producing B cells; and to deliver optimal helper signals to such B cells for their activation.

In humans, TSAbs are predominantly of the Th1-dependent IgG1 isotype and are light chain-restricted [43]. Also, recently, monoclonal TSAbs belonging to the mouse IgG2a [44] or hamster IgG2[45] subclasses have been produced, suggesting Th1 cell involvement in TSAb production. Genetic immunization via the muscle or the skin [39,46] is ideal in promoting generation of Th1 cells because unmethylated CpG motifs in plasmid DNA are recognized by Toll-like receptor 9 (TLR9) [47] and can trigger antigen presenting cells to produce pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IFN-α and IL-12 [39]. This adjuvant effect is evident even in Th2-biased BALB/c mice [48]. Recently, i.m. challenges of BALB/c mice with TSHR-plasmid DNA has, indeed, shown priming of TSHR-specific Th1 cells [20] but this was not sufficient to induce hyperthyroidism. Our results are in agreement with those of Nagayama et al. [21] who showed significant inhibition of TSAb production and reduction in hyperthyroidism in BALB/c mice after coinjection of adenoviral vectors expressing TSHR and IL-4. Coinjection of adenovirus-infected TSHR-expressing dendritic cells with the Th2 cell-inducing adjuvant alum also has been shown to suppress antibody production and disease development [42]. Collectively, these data contrast with experimental evidence supporting Th2 cell participation in murine GD such as the presence of intrathyroidal IL-4-secreting T cells in NMRI mice i.m. immunized with TSHR DNA [17]; the facilitating role of Th2 adjuvants in the development of hyperthyroidism [14]; and the resistance of IL-4-knock out mice to GD development after challenge with TSHR-expressing cells [49]. These apparently conflicting data cannot be currently reconciled. Our finding that coinjection of TSHR- and IL-12-producing plasmids does not enhance the incidence of GD is also in agreement with parallel observations using adenoviral vectors [21]. The lack of GD enhancement by coadministration of pcDNA3-IL-12 plasmid could be attributed to an inability to improve an already optimal adjuvant effect mediated by CpG motifs in pcDNA3-TSHR.

The histological signs of thyroid follicular cell activation and protrusion in the follicular lumen, associated with hyperthyroidism, are similar to those observed in most [13,17,19,42]– but not all [16]- murine GD studies. We do not understand the reasons behind the follicular heterogeneity observed in one hyperthyroid mouse (Fig. 2a,d) vis a vis the homogeneous follicular activation in another (Figs 2c,f). It has been reported [19] that activated follicles tend to predominate in mice with high T4 values (> 11–12 µg/dl) but both of our mice had TT4 values in that interval (13·4 vs. 16·2 µg/dl, respectively, on week 10). Nevertheless, the juxtaposition of follicles with inactive and active epithelium is quite interesting and reveals a follicular autonomy in the reception of stimulatory signals by TSAbs. The lack of an intrathyroidal mononuclear cell infiltrate in our thyrotoxic mice is in contrast to the findings of Costagliola [17] but in agreement with observations in adenovirus-induced GD [19,42]. Since TSHR has been shown to encompass pathogenic determinants that elicit thyroid-infiltrating cells [5,50] it is puzzling why i.d. challenge with TSHR DNA does not activate such cells. The reasons behind these apparently conflicting observations will be better known once the mechanisms of TSHR presentation are elucidated in various models.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrates that genetic immunization of inbred mice with TSHR DNA administered via the i.d. route can elicit the salient features of GD. Our data do not provide support for the notion that TSHR-induced murine GD relies on the activation of Th2 cells for the delivery of helper signals to TSAb-producing B cells. Genetic immunization offers new opportunities to assess the relative importance of many contributing factors in the development of GD. For example, a common feature has been the use of xenogeneic (human) TSHR for induction of GD symptoms in mice. Clearly, the delineation of conditions that facilitate the breakdown of immune tolerance to self TSHR would be very valuable for understanding the development of human GD. New methodologies, such as the codelivery of pro-apoptotic genes [51] or alphaviral replicon-encoding DNA vectors [52] offer great promise in this area.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr B.H. Barber for his kind gift of the IL-4- and IL-12-producing plasmids. This work was supported by a grant from the Canadian Institutes for Health Research through the Regional Partnerships Programme.

References

- 1.Rapoport B. The thyrotropin receptor. In: Braverman LE, Utiger RD, editors. Werner & Ingbar's The Thyroid: a fundamental and clinical text. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2000. pp. 219–27. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davies TF. Graves’ Disease. Pathogenesis. In: Braverman LE, Utiger RD, editors. Werner & Ingbar's The Thyroid: a fundamental and clinical text. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2000. pp. 518–31. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ludgate M. Animal models of Graves’ disease. Eur J Endocrinol. 2000;142:1–8. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1420001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marion S, Braun JM, Ropars A, Kohn LD, Charreire J. Induction of autoimmunity by immunization of mice with human thyrotropin receptor. Cell Immunol. 1994;158:329–41. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1994.1280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang SH, Carayanniotis G, Zhang Y, Gupta M, McGregor AM, Banga JP. Induction of thyroiditis in mice with thyrotropin receptor lacking serologically dominant regions. Clin Exp Immunol. 1998;113:119–25. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1998.00627.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Costagliola S, Many MC, Stalmans-Falys M, Tonacchera M, Vassart G, Ludgate M. Recombinant thyrotropin receptor and the induction of autoimmune thyroid disease in BALB/c mice: a new animal model. Endocrinology. 1994;135:2150–9. doi: 10.1210/endo.135.5.7956939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Costagliola S, Alcalde L, Tonacchera M, Ruf J, Vassart G, Ludgate M. Induction of thyrotropin receptor (TSH-R) autoantibodies and thyroiditis in mice immunised with the recombinant TSH-R. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;199:1027–34. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seetharamaiah GS, Desai RK, Dallas JS, Tahara K, Kohn LD, Prabhakar BS. Induction of TSH binding inhibitory immunoglobulins with the extracellular domain of human thyrotropin receptor produced using baculovirus expression system. Autoimmunity. 1993;14:315–20. doi: 10.3109/08916939309079234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wagle NM, Dallas JS, Seetharamaiah GS, Fan JL, Desai RK, Memar O, Rajaraman S, Prabhakar BS. Induction of hyperthyroxinemia in BALB/C but not in several other strains of mice. Autoimmunity. 1994;18:103–12. doi: 10.3109/08916939409007983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vlase H, Weiss M, Graves PN, Davies TF. Characterization of the murine immune response to the murine TSH receptor ectodomain. induction of hypothyroidism and TSH receptor antibodies. Clin Exp Immunol. 1998;113:111–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1998.00622.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carayanniotis G, Huang GC, Nicholson LB, Scott T, Allain P, McGregor AM, Banga JP. Unaltered thyroid function in mice responding to a highly immunogenic thyrotropin receptor. implications for the establishment of a mouse model for Graves’ disease. Clin Exp Immunol. 1995;99:294–302. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1995.tb05548.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shimojo N, Kohno Y, Yamaguchi K, et al. Induction of Graves-like disease in mice by immunization with fibroblasts transfected with the thyrotropin receptor and a class II molecule. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:11074–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.20.11074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rao PV, Watson PF, Weetman AP, Carayanniotis G, Banga JP. Contrasting activities of thyrotropin receptor antibodies in experimental models of Graves’ disease induced by injection of transfected fibroblasts or deoxyribonucleic acid vaccination. Endocrinology. 2003;144:260–6. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-220688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kita M, Ahmad L, Marians RC, Vlase H, Unger P, Graves PN, Davies TF. Regulation and transfer of a murine model of thyrotropin receptor antibody mediated Graves’ disease. Endocrinology. 1999;140:1392–8. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.3.6599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jaume JC, Rapoport B, McLachlan SM. Lack of female bias in a mouse model of autoimmune hyperthyroidism (Graves’ disease) Autoimmunity. 1999;29:269–72. doi: 10.3109/08916939908994746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaithamana S, Fan J, Osuga Y, Liang SG, Prabhakar BS. Induction of experimental autoimmune Graves’ disease in BALB/c mice. J Immunol. 1999;163:5157–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Costagliola S, Many MC, Denef JF, Pohlenz J, Refetoff S, Vassart G. Genetic immunization of outbred mice with thyrotropin receptor cDNA provides a model of Graves’ disease. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:803–11. doi: 10.1172/JCI7665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Costagliola S, Rodien P, Many MC, Ludgate M, Vassart G. Genetic immunization against the human thyrotropin receptor causes thyroiditis and allows production of monoclonal antibodies recognizing the native receptor. J Immunol. 1998;160:1458–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nagayama Y, Kita-Furuyama M, Ando T, Nakao K, Mizuguchi H, Hayakawa T, Eguchi K, Niwa M. A novel murine model of Graves’ hyperthyroidism with intramuscular injection of adenovirus expressing the thyrotropin receptor. J Immunol. 2002;168:2789–94. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.6.2789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pichurin P, Yan XM, Farilla L, Guo J, Chazenbalk GD, Rapoport B, McLachlan SM. Naked TSH receptor DNA vaccination: a TH1 T cell response in which interferon-gamma production, rather than antibody, dominates the immune response in mice. Endocrinology. 2001;142:3530–6. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.8.8301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nagayama Y, Mizuguchi H, Hayakawa T, Niwa M, McLachlan SM, Rapoport B. Prevention of autoantibody-mediated Graves’-like hyperthyroidism in mice with IL-4, a Th2 cytokine. J Immunol. 2003;170:3522–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.7.3522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Watanabe A, Raz E, Kohsaka H, Tighe H, Baird SM, Kipps TJ, Carson DA. Induction of antibodies to a kappa V region by gene immunization. J Immunol. 1993;151:2871–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Raz E, Carson DA, Parker SE, et al. Intradermal gene immunization: the possible role of DNA uptake in the induction of cellular immunity to viruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:9519–23. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.20.9519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McIntosh RS, Mulcahy AF, Hales JM, Diamond AG. Use of Epstein-Barr virus-based vectors for expression of thyroid auto-antigens in human B-lymphoblastoid cell lines. J Autoimmun. 1993;6:353–65. doi: 10.1006/jaut.1993.1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nagayama Y, Kaufman KD, Seto P, Rapoport B. Molecular cloning, sequence and functional expression of the cDNA for the human thyrotropin receptor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1989;165:1184–90. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(89)92727-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Libert F, Lefort A, Gerard C, Parmentier M, Perret J, Ludgate M, Dumont JE, Vassart G. Cloning, sequencing and expression of the human thyrotropin (TSH) receptor: evidence for binding of autoantibodies. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1989;165:1250–5. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(89)92736-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Misrahi M, Loosfelt H, Atger M, Sar S, Guiochon-Mantel A, Milgrom E. Cloning, sequencing and expression of human TSH receptor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1990;166:394–403. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(90)91958-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Frazier AL, Robbins LS, Stork PJ, Sprengel R, Segaloff DL, Cone RD. Isolation of TSH and LH/CG receptor cDNAs from human thyroid: regulation by tissue specific splicing. Mol Endocrinol. 1990;4:1264–76. doi: 10.1210/mend-4-8-1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Iwasaki A, Stiernholm BJ, Chan AK, Berinstein NL, Barber BH. Enhanced CTL responses mediated by plasmid DNA immunogens encoding costimulatory molecules and cytokines. J Immunol. 1997;158:4591–601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sideras P, Bergstedt-Lindqvist S, Severinson E, et al. IgG1 induction factor: a single molecular entity with multiple biological functions. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1987;213:227–36. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4684-5323-2_22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yokota T, Arai N, Lee F, Rennick D, Mosmann T, Arai K. Use of a cDNA expression vector for isolation of mouse interleukin 2 cDNA clones. expression of T-cell growth-factor activity after transfection of monkey cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:68–72. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.1.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Verginis P, Stanford MM, Carayanniotis G. Delineation of five thyroglobulin T cell epitopes with pathogenic potential in experimental autoimmune thyroiditis. J Immunol. 2002;169:5332–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.9.5332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rao VP, Carayanniotis G. Contrasting immunopathogenic properties of highly homologous peptides from rat and human thyroglobulin. Immunology. 1997;90:244–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1997.00160.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schoenhaut DS, Chua AO, Wolitzky AG, et al. Cloning and expression of murine IL-12. J Immunol. 1992;148:3433–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Perret J, Ludgate M, Libert F, Gerard C, Dumont JE, Vassart G, Parmentier M. Stable expression of the human TSH receptor in CHO cells and characterization of differentially expressing clones. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1990;171:1044–50. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(90)90789-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Metcalfe R, Jordan N, Watson P, et al. Demonstration of immunoglobulin G, A, and E autoantibodies to the human thyrotropin receptor using flow cytometry. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:1754–61. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.4.8411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nicholson LB, Vlase H, Graves P, et al. Monoclonal antibodies to the human TSH receptor: epitope mapping and binding to the native receptor on the basolateral plasma membrane of thyroid follicular cells. J Mol Endocrinol. 1996;16:159–70. doi: 10.1677/jme.0.0160159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yewdell JW, Frank E, Gerhard W. Expression of influenza A virus internal antigens on the surface of infected P815 cells. J Immunol. 1981;126:1814–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gurunathan S, Klinman DM, Seder RA. DNA vaccines: immunology, application and optimization. Annu Rev Immunol. 2000;18:927–74. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Akbari O, Panjwani N, Garcia S, Tascon R, Lowrie D, Stockinger B. DNA vaccination: transfection and activation of dendritic cells as key events for immunity. J Exp Med. 1999;189:169–78. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.1.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Klinman DM, Sechler JM, Conover J, Gu M, Rosenberg AS. Contribution of cells at the site of DNA vaccination to the generation of antigen-specific immunity and memory. J Immunol. 1998;160:2388–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kita-Furuyama M, Nagayama Y, Pichurin P, McLachlan SM, Rapoport B, Eguchi K. Dendritic cells infected with adenovirus expressing the thyrotrophin receptor induce Graves’ hyperthyroidism in BALB/c mice. Clin Exp Immunol. 2003;131:234–40. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2003.02080.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Weetman AP, Yateman ME, Ealey PA, Black CM, Reimer CB, Williams RC, Jr, Shine B, Marshall NJ. Thyroid-stimulating antibody activity between different immunoglobulin G subclasses. J Clin Invest. 1990;86:723–7. doi: 10.1172/JCI114768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Costagliola S, Franssen JD, Bonomi M, Urizar E, Willnich M, Bergmann A, Vassart G. Generation of a mouse monoclonal TSH receptor antibody with stimulating activity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;299:891–6. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)02762-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ando T, Latif R, Pritsker A, Moran T, Nagayama Y, Davies TF. A monoclonal thyroid-stimulating antibody. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:1667–74. doi: 10.1172/JCI16991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sato Y, Roman M, Tighe H, et al. Immunostimulatory DNA sequences necessary for effective intradermal gene immunization. Science. 1996;273:352–4. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5273.352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wagner H. Interactions between bacterial CpG-DNA and TLR9 bridge innate and adaptive immunity. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2002;5:62–9. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(02)00287-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chu RS, Targoni OS, Krieg AM, Lehmann PV, Harding CV. CpG oligodeoxynucleotides act as adjuvants that switch on T helper 1 (Th1) immunity. J Exp Med. 1997;186:1623–31. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.10.1623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dogan RN, Vasu C, Holterman MJ, Prabhakar BS. Absence of IL-4, and not suppression of the Th2 response, prevents development of experimental autoimmune Graves’ disease. J Immunol. 2003;170:2195–204. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.4.2195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Costagliola S, Many MC, Stalmans-Falys M, Vassart G, Ludgate M. Transfer of thyroiditis, with syngeneic spleen cells sensitized with the human thyrotropin receptor, to naive BALB/c and NOD mice. Endocrinology. 1996;137:4637–43. doi: 10.1210/endo.137.11.8895327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sasaki S, Amara RR, Oran AE, Smith JM, Robinson HL. Apoptosis-mediated enhancement of DNA-raised immune responses by mutant caspases. Nat Biotechnol. 2001;19:543–7. doi: 10.1038/89289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Leitner WW, Hwang LN, deVeer MJ, et al. Alphavirus-based DNA vaccine breaks immunological tolerance by activating innate antiviral pathways. Nat Med. 2003;9:33–9. doi: 10.1038/nmxx. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]