Abstract

Chronic human Chagas' disease ranges from an asymptomatic to a severe cardiac clinical form. The involvement of the host's immune response in the development and maintenance of chagasic pathology has been demonstrated by several groups. We have shown that activated T-cells lacking CD28 expression are increased in the peripheral blood of chagasic patients (CP), suggesting a relationship between these cells and disease. In order to better characterize this cell population, determining their possible role in immunoregulation of human Chagas' disease, we evaluated the expression of TCR-Vbeta regions 2, 3·1, 5, 8 and 17, as well as the expression of IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-4 and IL-10 by CD28+ and CD28− cells from polarized indeterminate and cardiac CP. Flow cytometric analysis demonstrated equivalent TCR-Vbeta usage between CD4+CD28+ and CD4+CD28− cells from all groups (chagasic and healthy controls). However, there was a predominance of Vbeta5 expression in the CD28+ and CD28− populations in the CP groups (indeterminate and cardiac). Interestingly, CD8+CD28− cells from CP, but not from nonchagasic individuals, displayed a reduced frequency of most analysed Vbetas when compared with the CD8+CD28+ subpopulation. Comparison of V-beta expression in CD28+ or CD28− cell populations among individuals from different groups also showed several interesting differences. Functionally, cardiac CP displayed a higher frequency of IFN-γ, TNF-α and IL-4 producing lymphocytes than indeterminate CP. Correlation analysis between the frequency of cytokine expressing cells, and the frequency of CD4+ T-cells with differential expression of CD28 demonstrated that CD4+CD28− T-cells were positively correlated with TNF-α in cardiac and with IL-10 in indeterminate CP, suggesting that these cells might have an important regulatory role in human Chagas' disease.

Keywords: Chagas disease, CD28, T-cells, repertoire, cytokines

INTRODUCTION

Chagas' disease is an infection caused by the protozoan Trypanosoma cruzi and affects approximately 18 million of people in Latin America. The most prevalent form of transmission is through the insect vector, while transmission through blood transfusion has become a concern even in nonendemic areas [1]. The disease evolves through an acute to a chronic phase, where patients can be clinically asymptomatic (classified as indeterminate) or show cardiac and/or digestive alterations. Many studies have shown that morbidity in Chagas' disease is related to parasite factors as well as the host's immune response. T cells and the cytokines they produce, as well as B cells, are involved in the development and maintenance of disease in both experimental models [2–5] and human disease [6–10].

Studies regarding the immunological profile of chagasic patients have shown high percentages of circulating activated HLA-DR+ T cells [11]. Accordingly, activated T cells are the predominant cell type in chagasic cardiac inflammatory lesions [12]. Moreover, cytokine message analysis has shown the presence of both inflammatory as well as anti-inflammatory cytokines in peripheral blood cells of patients with indeterminate and cardiac clinical forms [7], whereas TNF-α+ and IFN-γ+ cells are predominant in cardiac lesion sites [12,13]. Recently, an association of IFN-γ expression and the development of severe cardiac disease has been demonstrated [14]. Some studies have attempted to determine the stimuli responsible for the activation of T cells in human Chagas' disease. Whereas parasite derived antigens are able to stimulate CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from chagasic patients in vitro[15,16], T cells that can recognize and proliferate in response to autologous antigens have also been detected in chagasic patients [17,18]. Recent studies analysing the T cell repertoire have shown a preferential expression of Vbeta5 by CD4+ T cells from chagasic patients both ex vivo as well as after in vitro stimulation with parasite antigens [19]. However, in situ analysis failed to demonstrate a biased T cell Vbeta repertoire, whereas a Valpha bias was observed [20]. These data suggest that a dominant antigenic target may be important in eliciting T cell responses in human Chagas' disease.

The mechanisms involved in cardiac tissue destruction in Chagas' disease are not completely understood. The predominance of CD8+ T cells, the detection of granzymeA+ cells, along with increased expression of MHC class I by cardiomyocytes in the inflammatory infiltrate, are all highly suggestive of cytotoxic functions [12]. It is likely that CD8+ T cells recognize and kill cardiomyocytes expressing MHC class I, leading to tissue damage. Interestingly, we have demonstrated that chronic chagasic patients present increased levels of CD8+CD28− T cells in their peripheral blood [21]. Studies concerning CD28 expression have demonstrated that these cells display exacerbated cytotoxic function [22]. Moreover, it has been shown that CD28− cells do not require costimulation to exert their effector functions [23]. Thus, CD8+CD28− cells are strong candidates to be key effector cells in eliciting tissue pathology in Chagas' disease. Alternatively, recent studies have suggested a suppressor role for CD28− cells [24,25], which could also be important considering the chronic nature of Chagas' disease. Thus, characterizing CD28− cells may provide important information about the mechanisms involved in the immunopathology in human Chagas' disease.

In this work, we analysed the TCR Vbeta repertoire as well as the production of key immunoregulatory cytokines (IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-10 and IL-4) by CD28− T cells from chagasic patients. These characteristics were evaluated in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells negative for CD28 and compared with their CD28+ counterparts. Several important phenotypic and functional differences were found between CD28− and CD28+ T cell populations from chagasic individuals suggesting that T cell populations defined by this phenotype display distinct antigen recognition ability, and different functions in human Chagas' disease.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

Chronic chagasic patients analysed in this study were from endemic areas within Minas Gerais, Brazil and were under the medical responsibility of Dr M. O. C. Rocha. Serological tests were positive in all patients studied. A detailed evaluation, including physical examinations, electrocardiograms (ECG) and chest X-rays were performed in each patient. After careful clinical analysis, three groups of patients with chronic disease were obtained: (I) indeterminate – patients with a positive serology for T. cruzi, normal electrocardiogram and normal cardiac and digestive radiological evaluation; (C) nondilated cardiopathy – patients with alterations in the electrocardiogram such as right/left branch block, but without cardiac enlargement; (DC) dilated cardiopathy – patients with alterations in the electrocardiogram such as right/left branch block and dilated left ventricle shown by echocardiography (left ventricular diastolic diameter = 55 mm). The results obtained were compared with those obtained from nonchagasic individuals (N). This work is part of a larger study, which has been approved by the Ethical Committee of Federal University of Minas Gerais. All patients were volunteers and were offered complete medial care independent of their willingness to participate in this study. Table 1 shows the characteristics for the entire group of patients in this study.

Table 1. Patient characterization.

| Group | Number of individuals | Years | Serology, ECG, Echocardiography |

|---|---|---|---|

| (I) Indeterminate | 12 | 26–59 | +, normal, normal |

| (C) Non-dilated cardiopathy | 18 | 30–62 | +, mild alterations, normal |

| (DC) Dilated cardiopathy | 11 | 26–61 | +, severe alterations, dilated cardiomyopathy |

| (N) Non-infected | 7 | 29–50 | –, normal, normal |

T. cruzi antigens

T. cruzi trypomastigotes (Y strain) were obtained from supernatants of an NTCT cell culture (clone 929; American Type Culture Collection CCL1) from mouse connective tissue. Approximately 1 × 106 cells were cultured at 37°C in 5% CO2 with DMEM (Dulbecco's Modified Essential Medium) pH 7·3, supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FCS (Fetal Calf Serum), 2 mm l-glutamine, 100UI/ml G penicillin, and 100 g/ml streptomycin. After adhesion and monolayer formation, the cells were infected with 2 × 106 trypomastigotes obtained from the blood of an experimentally infected mouse. The monolayer was extensively washed to remove extracellular parasites and cultured for 5 days with DMEM supplemented with 5% FCS at 37°C, 5% CO2. The supernatant containing trypomastigotes was harvested and centrifuged at 150 g for 5 min to eliminate cells in the pellet. Parasites used for preparation of T. cruzi soluble antigens were washed twice with phosphate buffer solution (PBS), centrifuged and the pellet obtained was kept in freezer −70°C. All preparations contained less than 10% amastigotes. Pellets of trypomastigotes were ressuspended with PBS pH 7·2, supplemented with protease inhibitors (1 mm EDTA, 2 mg/ml aprotinin, 2 mg/ml leupeptin, 50 mg/ml TLCK and 100 mg/ml PMSF) followed by three cycles of ultrasonication, for 30 s each at 4°C. The solution was centrifuged at 12 000 g for 10min at 4°C and the supernatant was submitted to protein quantification by the Bradford method. The T. cruzi soluble antigens (TRP) were stored at −70°C.

Preparation of PBMC for ex vivo analysis or in vitro culture with parasite-derived antigens

PBMC from chagasic patients or noninfected individuals were obtained by separating blood cells in a Ficol gradient, as described by Gazzinelli et al. [26]. Cells were washed three times in media and counted. PBMC from chagasic patients and noninfected individuals were used for ex vivo TCR-Vbeta usage analysis or for in vitro cultures. Cultures were set up using a concentration of 2 × 106 cells/well in a 24-well plate in the presence or absence of TRP (20 µg/ml final concentration) and were incubated for approximately 18 h. Brefeldin A (10 µg/ml) was added during the last 4 h of culture to impair protein secretion, allowing for cytokine intracellular staining, as previously done by us [27]. After the incubation period, cultures were harvested and submitted to flow cytometric analysis to evaluate the cytokine profile.

Monoclonal antibodies (Mabs)

The antibodies used for phenotypic and functional analysis were: anti-CD4-Cychrome (Cy), anti-CD8-Cy and anti-CD28- phycoerythrin (PE) purchased from Caltag; fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labelled anti-Vbeta3·1 and 5 purchased from T Cell Diagnostics; fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labelled anti-Vbeta2, 8, 17 purchased from Immunotech. The anticytokines antibodies used were PE-labelled anti-IL-4, IL-10, IFN-γ, TNF-α purchased from Caltag. As a control, nonrelated IgG1/IgG2a/IgG Mabs (FITC/PE/Cy) from Caltag were used.

Immunofluorescence

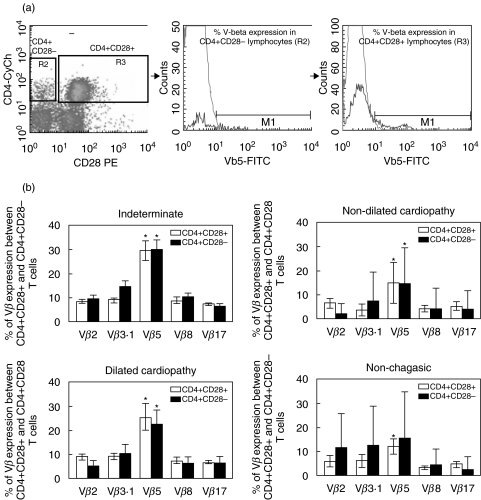

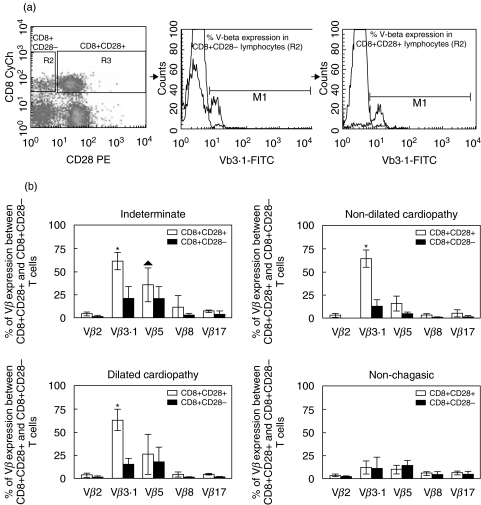

Fresh PBMC from chagasic patients were used for ex vivo repertoire analysis or cultured for cytokine analysis. PBMC from noninfected individuals were used for ex vivo analysis only. Approximately 2 × 105 cells, either before or after culture, were incubated with the different antibody solutions for 30 min at 4°C, washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7·2) and fixed in a formaldehyde-containing solution. The expression of the T cell repertoire was investigated using three-colour FACS analysis, combining differentially labelled anti-CD4 or anti-CD8 with anti-CD28 and anti-Vbeta. Fixed samples were maintained in the dark at 4°C until acquisition and analysis using FACSvantage (Becton-Dickinson). Cytokine expression was assessed in cells submitted to in vitro stimulation, as described above. Cells were collected and labelled for surface markers, as described above. After fixation, cells were permeabalized and stained with anticytokine monoclonal antibodies, washed and stored until acquisition. For all samples we collected a minimum of 20 000 cells. Figures 1a and 2a show representative dot-plots obtained by analysis of expression of CD4 and CD28 or CD8 and CD28, respectively, where we selected CD28− or CD28+ lymphocytes and then we generated representative histograms for evaluation of Vbeta expression in each subpopulation. All analyses were performed gating on CD4high or CD8high cells to assure T-cell analysis.

Fig. 1.

(a) Dot plot of CD4/CD28 and representative histograms of Vbeta5 expression percentage in both subpopulations CD4+CD28− and CD4+CD28+ 0. (b) Comparison of Vbeta expression between CD4+CD28+ (□) and CD4+CD28− (▪) cellular subpopulations from noninfected individuals (n = 7), indeterminate patients (n = 12), patients with nondilated cardiopathy (n = 18) and patients with dilated cardiopathy (n = 11). Results are mean ± SD and the statistical differences are shown with P < 0·05. *Vbeta5 > Vβ 2, 3·1, 8 and 17.

Fig. 2.

(a) Dot plot of CD8/CD28 and representative histograms of Vbeta3·1 expression percentage in both subpopulations CD8+CD28− and CD8+CD28+. (b) Comparison of Vbeta expression between CD4+CD28+ (□) and CD4+CD28− (▪) cellular subpopulations from noninfected individuals (n = 7), indeterminate patients (n = 12), patients with nondilated cardiopathy (n = 18) and patients with dilated cardiopathy (n = 11). Results are mean ± SD values and the statistical differences are shown with P < 0·05. *Vbeta3·1 > Vbeta2, 8 and 17. ▴ Vbeta5 > Vbeta2, 8 and 17.

Statistical analysis

The statistical test of Tukey-Kramer from the JMP software (SAS) was applied to ascertain statistically significant differences between the groups under comparison. Additionally, we used regression analysis to assess the existence of correlations between different cell populations. Results were considered statistically significant using an alpha of 5%.

RESULTS

TCR V-beta analysis in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells with differential expression of CD28

We have previously shown that CD4+ T cells from chagasic patients display a preferential expression of Vbeta5 [19]. In order to determine whether this preferential expression was contained within the CD28+ or the CD28− subpopulations, and to further compare the expression of other TCR-Vbeta regions between CD28+ and CD28− T cells, we determined the expression of Vbeta2, 3·1, 5, 8 and 17. These studies demonstrated that Vbeta5 is over-represented in both the CD4+CD28+ and CD4+CD28− cell populations in chagasic patients (Fig. 1b). In nonchagasic individuals, statistical significance was only achieved when comparing expression of Vbeta5 with other Vbetas within the CD4+CD28+ cells. The overall repertoire is statistically similar when comparing between CD4+CD28+ and CD4+CD28− cells in all the groups analysed (chagsic and healthy controls)(Fig. 1b).

Analysis of Vbeta expression by CD8+ T cells with differential expression of CD28 was also performed using three-colour FACS analysis. We observed a preferential expression of Vbeta3·1 by CD8+CD28+ cells in relation to other Vbetas analysed in all groups of chagasic patients (Fig. 2b). Statistical significance was observed when comparing the expression of Vbeta5 with the expression of Vbeta2, 8 and 17, within CD8+CD28+ cells only for the indeterminate chagasic patients (Fig. 2b). No preferential Vbeta expression was detected within CD8+CD28+ or CD8+CD28− cells from nonchagasic individuals (Fig. 2b). Interestingly, we observed a dramatic decrease in the frequency of most Vbeta regions analysed within the CD8+CD28− subpopulation from chagasic patients, as compared to the frequency expression within the CD8+CD28+ cells (Fig. 2b).

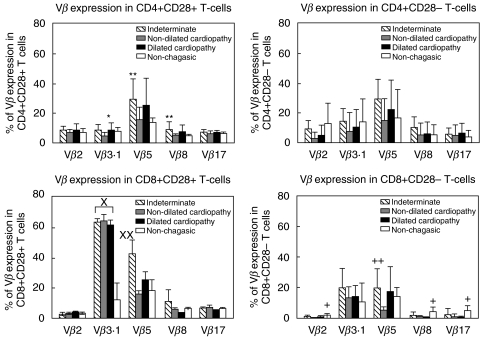

We performed comparative analysis of Vbeta expression in T cells with differential expression of CD28 among individuals from the different clinical groups. Our analysis showed that although no differences between groups were seen in Vbeta expression within the CD4+CD28− cells, CD4+CD28+ cells from indeterminate chagasic patients displayed a significantly higher frequency of Vbeta8 as compared to nondilated cardiac chagasic patients and Vbeta5 expression as compared to nonchagasic patients or cardiac patients with nondilated cardiopathy (Fig. 3). Similarly, CD8+CD28+ cells from indeterminate patients displayed a higher expression of Vbeta5, as compared to nondilated cardiac patients (Fig. 3). A striking increase in the frequency of Vbeta3 expression was also observed within CD8+CD28+ cells from all chagasic patient groups as compared to nonchagasic individuals (Fig. 3). Interestingly, when comparing Vbeta frequencies within CD8+CD28− cells among individuals from different groups, we observed a statistically significant decrease in the frequencies of V-betas 2, 8 and 17 in CD8+CD28− cells from cardiac chagasic patients when compared to nonchagasic individuals (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Comparison of Vbeta expression in T-cells with differential CD28 expression between nonchagasic individuals and chagasic patients with different clinical forms. Results are presented as mean ± SD values and the statistical differences are shown with P < 0·05. *CD4+CD28+ Vbeta3·1 dilated cardiopahy > nondilated cardiopathy; **CD4+CD28+ Vbeta5 and Vbeta8 indeterminate >non-chagasic; ×CD8+CD28+ Vbeta3·1 all chagasic > nonchagasic; ××CD8+CD28+ Vbeta5 indeterminate > nonchagasic; +CD8+CD28− Vbeta2, 8 and 17 nonchagasic > all cardiac chagasic patients; ++CD8+CD28-Vbeta5 indeterminate > nonchagasic.

Phenotypically distinct T cells express different cytokines in human Chagas' disease

To determine if patients with different clinical forms of Chagas' disease express qualitatively and/or quantitatively different cytokine profiles, the overall frequency of lymphocytes producing key immunoregulatory cytokines (IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-4 and IL-10), was determined for the lymphocyte populations. PBMC from chagasic patients were analysed following short-term stimulation with trypomastigote antigens, using flow cytometry. For this analysis all cardiac patients were grouped together, despite the severity of cardiopathy due to the low number of patients analysed in each sub-stage of cardiac disease.

First, it was determined that the total percentage of lymphocytes expressing IFN-γ, IL-4 and TNF-α was increased in cardiac (nondilated and dilated cardiopathy) as compared to indeterminate chagasic patients, whereas the frequency of IL-10+ cells was similar between the groups (Table 2).

Table 2. Mean percentages (± SD) of cytokine expression within the lymphocyte gate in PBMC from indeterminate (I) and cardiac (C + DC) chagasic patients after stimulation with trypomastigote antigens.

| Clinical form | ||

|---|---|---|

| % of cytokine expression | Indeterminate (I) | Cardiac (C + DC) |

| %CD4+ IFN-γ+ | 0·22 ± 0·13 | 0·43 ± 0·22* |

| %CD8+ IFN-γ+ | 0·15 ± 0·17 | 0·17 ± 0·07 |

| %IFN-γ total | 0·94 ± 0·45 | 2·27 ± 1·19** |

| %CD4/TNF-α+ | 0·35 ± 0·18 | 0·40 ± 0·22 |

| %TNF-α total | 0·93 ± 0·46 | 2·26 ± 1·54† |

| %CD4/+IL-4+ | 0·48 ± 0·48 | 0·24 ± 0·10 |

| %IL-4 total | 1·13 ± 0·70 | 2·78 ± 1·86‡ |

| %CD4+/IL-10+ | 0·69 ± 0·62 | 0·38 ± 0·27 |

| %IL-10 total | 1·67 ± 1·23 | 3·23 ± 2·39 |

n-values: indeterminate 9, cardiac 11.

Percentage of CD4+ IFN-γ+ cells was higher in cardiac than in indeterminate patients; Percentage total of

IFN-γ,

TNF-αand

IL-4 was higher in cardiac than in indeterminate patients.

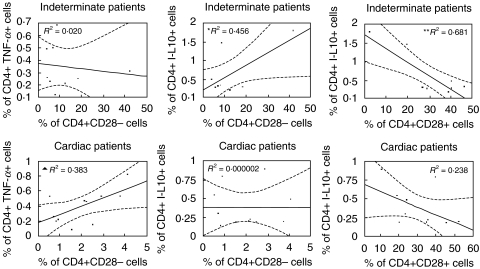

In order to determine if there exists a correlation between the frequency of cytokine producing lymphocytes and the frequency of possibly immunoregulatory CD4+ or CD8+ T cells with differential expression of CD28, a correlation analysis was performed between the frequency of cells expressing each cytokine and CD4+ or CD8+ T cells expressing or lacking CD28.

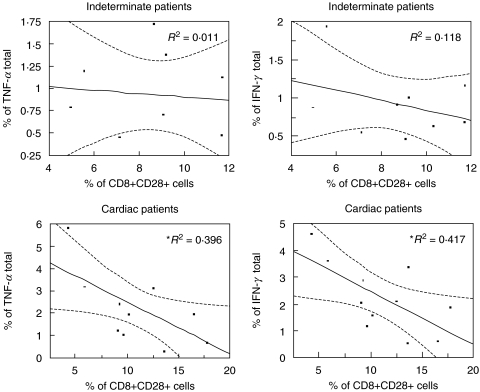

Analysis of cells from indeterminate and cardiac patients revealed no significant correlations between CD8+CD28− cells and the expression of the different cytokines (data not shown). However, we observed a negative correlation between the frequency of CD8+CD28+ cells and the frequency of lymphocytes producing the inflammatory cytokines, TNF-α or IFN-γ in cardiac patients (Fig. 4). This indicates that the lower the frequency of CD8+CD28+ cells, the higher the frequency of these inflammatory cytokines in cardiac patients. Correlation analysis between CD4+ cells with differential expression of CD28 and the expression of IFN-γ were not statistically significant (data not shown). However, we observed a positive correlation between the frequency of CD4+ cells expressing TNF-α and the frequency of CD4+CD28− cells in cardiac, but not indeterminate chagasic patients (Fig. 5). On the other hand, this same cell population was positively correlated with IL-10 expression in indeterminate, but not cardiac patients (Fig. 5). Lastly, the frequency of CD4+CD28+ cells was also negatively correlated with IL-10 expression in indeterminate patients (Fig. 5). Thus a number of interrelated correlations were seen between the frequency of cytokine producing cells and an accompanying increase or decrease in subpopulations of T cells expressing or lacking CD28.

Fig. 4.

Regression analysis between the frequencies of cells expressing TNF-α or IFN-γ and CD8+CD28+ T cells from indeterminate and cardiac patients. *Negative correlation between the frequencies of cells expressing TNF-α or IFN-γ and CD8+CD28+ T cells from cardiac patients. Statistical differences are shown with P < 0·05.

Fig. 5.

Regression analysis between the frequency of cells expressing TNF-α or IL-10 and CD4+CD28+ or CD28− T cells from indeterminate and cardiac patients. *Positive correlation between the frequency of CD4+ IL-10+ and CD4+CD28− cells from indeterminate patients. **Negative correlation between the frequency of CD4+ IL-10+ and CD4+CD28+ cells from indeterminate patients. ▴ Positive correlation between the frequency of CD4+ TNF-α+ and CD4+CD28− cells from cardiac patients. Statistical differences are shown with P < 0·05.

DISCUSSION

Although the exact mechanisms involved in the development of pathology in human Chagas' disease have not been completely clarified, the involvement of the host's immune system, in particular that of T lymphocytes, in the development of disease is well established. Early studies concerning T cell reactivity in human Chagas' disease have shown the occurrence of immunosuppression during the acute phase of the disease [28], whereas an intense proliferative response and cytokine expression is observed during chronic disease [4,7,14,15]. Quantitative analysis of the frequency of activated T cells in the peripheral blood of chagasic patients has shown a high frequency of T cells expressing HLA-DR [11] or lacking CD28 [21]. Moreover, evidence of in situ T cell activation, especially of CD8+ T cells, has been demonstrated by several authors [12,29,30], suggesting a role for these activated cells in disease. The present study analyses the Vbeta TCR repertoire as well as the functional characteristics of T cells with differential expression of CD28 from polarized indeterminate and cardiac patients. In this study we describe several important differences in repertoire expression when comparing chagasic to nonchagasic individuals, as well as clear differences in the frequency of antigen specific cytokine producing lymphocytes between individuals with distinct clinical evolution of disease. Finally, we also observed differences between CD28+ and CD28− T cell populations between patient groups, suggesting that differential expression of CD28 may lead to distinct functions.

Some studies concerning the origin of CD28− cells have suggested that they represent an independently differentiated cell population, in relation to CD28+ cells [31]. However, most studies suggest that these T cells are actually derived from CD28+ cells that, upon differentiation, lose CD28, acquiring distinct functional activities [32,33]. In fact, studies using T cell clones have shown a re-expression of CD28 in cells that initially displayed the CD28− phenotype [22]. Moreover, analysis of CD28− T cells following BRDU-labelling of CD28+ cells has shown that they represent distinct differentiation stages of the same cell [32]. Repertoire analysis in CD28− cells has also shown the occurrence of a repertoire bias in CD4+CD28− cell, that were initially identified as CD4+CD28+ cells [34].

Differential expression of CD28 by T cells identifies morphologically and functionally distinct cell populations. It has been shown that CD28+ cells have a higher proliferative capacity than CD28− cells [35], but that the cytotoxic ability of the latter is greater [22,36]. The identification of distinct cytokine patterns in CD28+ and CD28− cells has allowed for the proposal of a functional dichotomy between these cells [37], possibly due to the different costimulatory requirements of CD28+ and CD28− cells, which could influence differentiation towards an inflammatory or anti-inflammatory profile [38]. Morphological analysis of CD28+ and CD28− cells has shown that CD28- cells display characteristics of activated/memory lymphocytes [31].

It has been hypothesized that CD28− cells are a subset of previously activated T cells, with a great ability to promptly respond in vivo[39]. While the fact that CD28− cells are efficient effectors of immune functions is well accepted, some studies have suggested that these cells are susceptible to apoptosis, which could represent a mechanism of control of their exacerbated cytotoxic functions [40]. Conversely, the resistance of CD28− cells to apoptosis has also been reported [41]. Recent studies have also suggested that CD28− cells display suppressor functions, suggesting an important role for these cells in assuring the success of organ transplantation [24]. Thus, CD28− cells may represent a special T cell subpopulation with intense effector capacity, associated with self-regulating abilities. These characteristics have stimulated many studies to delineate the possible role of these cells in human diseases.

CD28– T cells have been associated with several pathologies, such as HIV and other viral infections [36,42], autoimmune diseases [43], as well as senescence mechanisms [37]. Interestingly, recent studies have shown that CD28 deficient mice exhibited a markedly exacerbated T. cruzi infection, with low production of IFN-γ[44]. We have previously shown an elevated frequency of CD28- cells in the peripheral blood of chagasic patients. Based on these findings we hypothesized that these cells could play an important role in the pathology of the disease, through increased cytolytic function and liberation of costimulation requirements. Thus, these cells could potentially recognize and kill cardiomyocytes, leading to tissue damage. Moreover, a self-controlling mechanism suggested for these cells is consistent with the long-lasting nature of Chagas' disease, where the patient may live for many years even in the presence of cardiopathy [45].

Our previous studies have shown that chagasic patients display preferential expression of the TCR-Vbeta5 in CD4+ T cells [19]. In this work, we determined that this biased repertoire was not restricted to either CD4+CD28+ or CD4+CD28− cells, but instead was contained in both. Moreover, the overall repertoire of these two populations was similar. These data suggest a similar antigenic recognition capacity for these two distinct populations. We observed a striking increase in the expression of Vbeta3·1 in CD8+CD28+ cells from all groups of chagasic patients. Previous studies have demonstrated that expression of Vbeta3·1 is controlled by genetic polymorphisms [46,47]. Whether a genetic polymorphism in the Vbeta 3 locus is associated with Chagas' disease is an intriguing question. However, the fact that this increase is related to a specific cell population (CD8+CD28+) suggests the involvement of immunological mechanism rather than genetic polymorphism.

Preferential expression of Vbeta5 was only observed in indeterminate patients. This difference may reflect the recognition of unique antigenic determinants in indeterminate and cardiac patients, a consequence of the different parasite strains [48] or host components involved in these two forms of the disease. In favour of this hypothesis, we have shown that stimulation with trypomastigote antigens leads to an increase in Vbeta5 in cardiac but not indeterminate patients [19]. Alternatively, it is possible that Vbeta5 expressing cells could have left the bloodstream and are present in the cardiac infiltrate. Cunha-Netto et al.[20] did not observe a Vbeta bias in cardiac tissue of chagasic patients. However, since these authors worked with unpurified cells, it is possible that a bias within CD8+CD28+ cells existed but was masked by other cell populations. Interestingly, we observed that the repertoire of CD8+CD28+ and CD8+CD28− cells is different in chagasic but not in nonchagasic individuals. There was a marked decrease in the frequency of most Vbeta regions analysed in the CD28− cells from chagasic patients, suggesting that another Vbeta region, different from those analysed here, may be expanded in this cell population. This suggests different antigenic recognition between these two populations and, at the same time, suggests the existence of a preferential antigenic target for CD8+CD28− cells in Chagas' disease. Further analysis is needed to clarify this finding.

Analysis of cytokine expression by T cells from chagasic patients using intracytoplasmic staining showed that cardiac patients display higher frequency of cells expressing IFN-γ, TNF-α and IL-4 as compared to indeterminate patients, confirming the concomitant presence of inflammatory and modulatory cytokines in long-lasting disease, as previously demonstrated by us [7]. Whereas T cells seem to be an important source of the measured cytokines, our data suggest that other cells are relevant for their production. We have recently shown that CD4−CD8− lymphocytes, although in relatively low frequency in the circulation, are an important source of IFN-γ in human leishmaniasis [27]. Thus, it is possible that these cells are important for IFN-γ production in human Chagas' disease. CD8+ T cells have been described as potential producers of TNF-α[42] and, thus, they could be involved in the production of this cytokine, along with the CD4+ T cells. Both CD8+ and CD4−CD8− cells are also able to produce IL-4 and could potentially account for the additional production of IL-4 other than CD4+ T cells [49]. We have previously demonstrated that CD5+ B cells are increased in the peripheral blood of chagasic patients [11] and others have shown that these cells are involved in the production of IL-10 [50]. These data suggest that B-1 cells might be an important source of this anti-inflammatory cytokine in human Chagas' disease.

Correlation analysis between the frequencies of cells with differential expression of CD28 and cytokine expression have shown a negative correlation between CD8+CD28+ cells and the frequency of IFN-γ and TNF-α expressing cells in cardiac patients. Thus, the lower the frequency of CD8+CD28+ cells, the higher the frequency of these inflammatory cytokines. Although a direct correlation was not found between CD8+CD28− cells and these inflammatory cytokines, the decrease of CD28+ cells is necessarily associated with a relative increase in CD28− cells. Thus, it is possible that these cells contribute to inflammatory cytokine expression. The lack of a direct correlation may be due to the fact that the frequency of cytokine expressing CD8+CD28− cells is very low. This is consistent with other studies showing that CD8+CD28− cells, while being active effectors, are poor cytokine producers [51].

CD4+CD28− cells displayed a different behaviour with respect to cytokine expression between the two clinical forms analysed. We observed that while these cells were positively correlated with IL-10 expression in indeterminate patients, they were positively correlated with TNF-α in cardiac patients. These results point to the differential involvement of a phenotypically defined cell population in Chagas' disease. We have previously shown that CD4+CD28− cells are increased in the peripheral blood of cardiac and indeterminate chagasic patients. Here we show that, although quantitatively similar between the two clinical forms, these cells may exert opposite effects in each group of patients. It is possible that in indeterminate patients these cells are related to the control of the inflammatory responses through the induction of IL-10 production and that in cardiac patients they act inversely by favouring the production of TNF-α. These data suggest an important role for CD4+CD28− cells in the immunoregulation of human Chagas' disease.

We have demonstrated that T cells with differential expression of CD28 display distinct phenotypic and functional characteristics in patients with indeterminate and the cardiac clinical forms of Chagas' disease. Due to the fact that we studied chronic patients, it is impossible to determine whether the observed differences between cell populations and clinical forms are a cause or consequence of the disease. However, the data presented in this work reflect the actual picture of the immune profile of indeterminate and cardiac chagasic patients, suggesting possible mechanisms for control or development of the pathology associated with human Chagas' disease.

Acknowledgments

This investigation received financial support from the UNDP/World Bank/WHO Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Disease (TDR); WOD, CASM and KJG are CNPq fellows. We would like to thank Dr Brian Kotzin for helpful discussions concerning the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Schofield CJ, Dias JC. A cost-benefit analysis of Chagas disease control. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1991;86:285–95. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02761991000300002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garg N, Tarleton RL. Genetic immunization elicits antigen-specific protective immune responses and decreases disease severity in Trypanosoma cruzi infection. Infect Immun. 2002;70:5547–55. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.10.5547-5555.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kumar S, Tarleton RL. Antigen-specific Th1 but not Th2 cells provide protection from lethalTrypanosoma cruzi infection in mice. J Immunol. 2001;166:4596–603. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.7.4596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gazzinelli RT, Oswald IP, Hieny S, James SI, Sher A. The microbicidal activity of interferon-gamma-treated macrophages against Trypanosoma cruzi involves na 1-arginine-dependent, nitrogen oxide-mediated mechanism inhibitable by interleukin-10 and transforming growth factor-beta. European J Immunol. 1992;22:2501–6. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830221006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Freire-de-Lima CG, Nascimento DO, Soares MB, Bozza PT, Castro-Faria-Neto HC, de Mello FG, DosReis GA, Lopes MF. Uptake of apoptotic cells drives the growth of a pathogenic trypanosome in macrophages. Nature. 2000;403:199–203. doi: 10.1038/35003208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Higuchi MD, Reis MM, Aiello VD, Benvenuti LA, Gutierrez PS, Bellotti G, Pileggi F. Association of an increase in CD8+ T cells with the presence of Trypanosoma cruzi antigens in chronic, human, chagasic myocarditis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1997;56:485–9. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1997.56.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dutra WO, Gollob KJ, Pinto-Dias JC, Gazzinelli G, Correa-Oliveira R, Coffman RL, Carvalho-Parra JF. Cytokine mRNA profile of peripheral blood mononuclear cells isolated from individuals with Trypanosoma cruzi chronic infection. Scand J Immunol. 1997;45:74–80. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.1997.d01-362.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferreira RC, Ianni BM, Abel LC, Buck P, Mady C, Kalil J, Cunha-Neto E. Increased plasma levels of tumor necrosis factor-alpha in asymptomatic/‘indeterminate’ and Chagas disease cardiomyopathy patients. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2003;98:407–11. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762003000300021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Michailowsky V, Luhrs K, Rocha MO, Fouts D, Gazzinelli RT, Manning JE. Humoral and cellular immune responses to Trypanosoma cruzi-derived paraflagellar rod proteins in patients with Chagas' disease. Infect Immun. 2003;71:3165–71. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.6.3165-3171.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Teixeira MM, Gazzinelli RT, Silva JS. Chemokines, inflammation and Trypanosoma cruzi infection. Trends Parasitol. 2002;18:262–5. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4922(02)02283-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dutra WO, Martins-Filho OA, Cancado JR, et al. Activated T and B lymphocytes in peripheral blood of patients with Chagas' disease. Int Immunol. 1994;6:499–506. doi: 10.1093/intimm/6.4.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reis DD, Jones EM, Tostes S, Gazzinelli G, Colley DG, McCurley T. Characterization of inflammatory infiltrates in chronic chagasic myocardial lesions. presence of TNF-alfa+ cells and dominance of granzyme A+, CD8+ lymphocytes. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1993;43:637–44. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1993.48.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rizzo LV, Cunha-Neto E, Teixeira AR. Autoimmunity in Chagas' disease: immunomodulation of autoimmune and T. cruzi-specific immune responses. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1988;83:360–2. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02761988000500023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gomes JAS, Bahia-Oliveira LMG, Rocha MOC, Martins-Filho OA, Gazzinelli G. Correa-Oliveira R.Evidence that development of severe cardiomyopathy in human Chagas'disease is due to a Th1 specific immune response. Infec Immunol. 2003;71:1185–93. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.3.1185-1193.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mosca W, Plaja J, Gallardo E, Garcia Barrios H. Immune response in human Chagas' disease I. lymphocyte blastogenesis in chagasic patients without evidence of cardiomyopathy. Acta Cient Venez. 1979;30:401–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dutra WO, Colley DG, Pinto-Dias JC, et al. Self and nonself stimulatory molecules induce preferential expansion of CD5+ B cells or activated T cells of chagasic patients, respectively. Scand J Immunol. 2000;51:91–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.2000.00648.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gazzinelli RT, Parra JF, Correa-Oliveira R, Cancado JR, Rocha RS, Gazzinelli G, Colley DG. Idiotypic/anti–idiotypic interactions in schistosomiasis and Chagas' disease. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1988;39:288–94. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1988.39.288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cunha-Neto E, Coelho V, Guilherme L, Fiorelli A, Stolf N, Kalil J. Autoimmunity in Chagas' disease. Identification of cardiac myosin-B13 Trypanosoma cruzi protein crossreactive T cell clones in heart lesions of a chronic Chagas' cardiomyopathy patient. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:1709–12. doi: 10.1172/JCI118969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Costa RP, Gollob KJ, Rocha MO, et al. T-cell repertoire analysis in acute and chronic human Chagas' disease: differential frequencies of V beta 5 expressing T cells. Scand J Immunol. 2000;51:511–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.2000.00706.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cunha-Neto E, Moliterno R, Coelho V, et al. Restricted heterogeneity of T cell receptor variable alpha chain transcripts in hearts of Chagas' disease cardiomyopathy patients. Parasite Immunol. 1994;16:171–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.1994.tb00337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dutra WO, Martins-Filho OA, Cancado JR, Pinto-Dias JC, Brener Z, Gazzinelli G, Carvalho JF, Colley DG. Chagasic patients lack CD28 expression on many of their circulating T lymphocytes. Scand J Immunol. 1996;43:88–93. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.1996.d01-9.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Azuma M, Phillips JH, Lanier LL. CD28– T lymphocytes. Antigenic and functional properties. J Immunol. 1993;150:1147–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Flynn K, Mullbacher A. Memory alloreactive cytotoxic T cells do not require costimulation for activation in vitro. Immunol Cell Biol. 1996;74:413–20. doi: 10.1038/icb.1996.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu Z, Tugulea S, Cortesini R, Suciu-Foca N. Specific suppression of T helper alloreactivity by allo-MHC class I-restricted CD8+CD28− T cells. Int Immunol. 1998;10:775–83. doi: 10.1093/intimm/10.6.775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chang CC, Ciubotariu R, Manavalan JS, et al. Tolerization of dendritic cells by Ts cells: the crucial role of inhibitory receptors ILT3 and ILT4. Nature Immunol. 2002;3:237–43. doi: 10.1038/ni760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gazzinelli G, Katz N, Rocha RS, Colley DG. Immune responses during human schistosomiasis mansoni. X. Production and standardization of an antigen-induced mitogenic activity by peripheral blood mononuclear cells from treated, but not active cases of schistosomiasis. J Immunol. 1983;30:2891–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bottrel RL, Dutra WO, Martins FA, et al. Flow cytometric determination of cellular sources and frequencies of key cytokine-producing lymphocytes directed against recombinant LACK and soluble Leishmania antigen in human cutaneous leishmaniasis. Infect Immun. 2001;69:3232–9. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.5.3232-3239.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ferreira MS. Chagas disease and immunosuppression. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1999;94:325–7. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02761999000700062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sato MN, Yamashiro-Kanashiro EH, Tanji MM, Kaneno R, Higuchi ML, Duarte AJ. CD8+ cells and natural cytotoxic activity among spleen, blood, and heart lymphocytes during the acute phase of Trypanosoma cruzi infection in rats. Infect Immun. 1992;60:1024–30. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.3.1024-1030.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cunha-Neto E, Rizzo LV, Albuquerque F, et al. Cytokine production profile of heart-infiltrating T cells in Chagas' disease cardiomyopathy. Braz J Med Biol Res. 1996;31:133–7. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x1998000100018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arosa F. A.CD8+CD28− T cells: certainties of a prevalent human T cell subset. Immunol Cell Biol. 2002;80:1–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1711.2002.01057.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Posnett DN, Edinger JW, Manavalan JS, Irwin C, Maradon G. Differentiation of human CD8 T cells. implications for in vivo persistence of CD8+CD28− cytotoxic effector clones. Int Immunol. 1999;11:229–41. doi: 10.1093/intimm/11.2.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Horiuchi T, Hirokawa M, Kawabata Y, et al. Identification of the T cell clones expanding within both CD8(+)CD28(+) and CD8(+)CD28(−) T cell subsets in recipients of allogenic hematopoietic cell grafts and its implication in post-transplant skewing of T cell repertoire. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2001;27:731–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1702859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wagner U, Pierer M, Kaltenhauser S, Wilke B, Seidel W, Arnold S, Hantzschel H. Clonally expanded CD4+CD28null T cells in rheumatoid arthritis use distinct combinations of T cell receptor BV and BJ elements. Eur J Immunol. 2003;33:79–84. doi: 10.1002/immu.200390010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Scheuring UJ, Sabzevari H, Theofilopoulos AN. Proliferative arrest and cell cycle regulation in CD8 (+)CD28(−) versus CD8(+)CD28 (+) T cells Hum. Immunol. 2002;63:1000–9. doi: 10.1016/s0198-8859(02)00683-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Borthwick NJ, Lowdell M, Salmon M, Akbar AN. Loss of CD28 expression on CD8+ T cells is induced by IL-2 receptor chain signalling cytokines and type I IFN, and increases susceptibility to activation-induced apoptosis. Int Immunol. 2000;12:1005–13. doi: 10.1093/intimm/12.7.1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chamberlain WD, Falta MT, Kotzin BL. Functional subsets within clonally expanded CD8 (+) memory T cells in elderly humans. Clin Immunol. 2000;94:160–72. doi: 10.1006/clim.1999.4832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kuchroo VK, Das MP, Brown JA, et al. B7–1 and B7–2 costimulatory molecules activate differentially the Th1/Th2 developmental pathways: application to autoimmune disease therapy. Cell. 1995;80:707–18. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90349-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Garcia S, DiSanto J, Stockinger B. Following the development of a CD4 T cell response in vivo: from activation to memory formation. Immunity. 1999;11:163–71. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80091-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tsukishiro T, Donnenberg AD, Whiteside TL. Rapid turnover of the CD8(+)CD28(−) T-cell subset of effector cells in the circulation of patients with head and neck cancer. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2003;52:599–607. doi: 10.1007/s00262-003-0395-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vallejo AN, Schirmer M, Weyand CM, Goronzy JJ. Clonality and longevity of CD4+CD28null T cells are associated with defects in apoptotic pathways. J Immunol. 2000;165:6301–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.11.6301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Eylar EH, Lefranc CE, Yamamura Y, Báez I, Colón-Martinez SL, Rodriguez N, Breithaupt TB. HIV infection and aging: enhanced Interferon- and Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha production by the CD8+CD28− T subset BMC. Immunol. 2001;2:10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2172-2-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shirai T, Hirose S, Okada T, Nishimura H. CD5 B cells in autoimmune disease and lymphoid malignancy. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1991;59:173. doi: 10.1016/0090-1229(91)90016-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Miyahira Y, Katae M, Kobayashi S, et al. Critical contribution of CD28-CD80/CD86 costimulatory pathway to protection from Trypanosoma cruzi infection. Infect Immunol. 2003;71:3131–7. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.6.3131-3137.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ferreira RC, Ianni BM, Abel LC, Buck P, Mady C, Kalil J, Cunha-Neto E. Increased plasma levels of tumor necrosis factor-alpha in asymptomatic/‘indeterminate’ and Chagas disease cardiomyopathy patients. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2003;98:407–11. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762003000300021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Donahue JP, Ricalton NS, Behrendt CE, Rittershaus C, Calaman S, Marrack P, Kappler JW, Kotzin B. Genetic analysis of low V beta 3 expression in humans. J Exp Med. 1994;179:1701–6. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.5.1701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.De Inocencio J, Choi E, Glass DN, Hirsch R. T-cell receptor repertoire differences between African Americans and Caucasians associated with the polymorphism of the TCRBV3S1 (V beta 3.1) Gene J Immunol. 1995;154:4836–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bustamante JM, Rivarola HW, Fernandez AR, Enders JE, Fretes R, Palma JA, Paglini-Oliva PA. Indeterminate Chagas' disease: Trypanosoma cruzi strain and re-infection are factors involved in the progression of cardiopathy. Clin Sci (Lond) 2003;104:415–20. doi: 10.1042/. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.O'Garra A, Murphy K. Role of cytokines in determining T-lymphocyte function. Curr Opin Immunol. 1994;6:458–66. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(94)90128-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.O'Garra A, Howard M. IL-10 production by CD5 B cells. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1992;651:182–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1992.tb24615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sad S, Kagi D, Mosmann TR. Perforin and Fas killing by CD8+ T cells limits their cytokine synthesis and proliferation. J Exp Med. 1996;184:1543–7. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.4.1543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]