Abstract

Tumour necrosis factor (TNF) is critical for sustained protective immunity against Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. To investigate the relative contributions of macrophage- and T cell-derived TNF towards this immunity T cells from wild-type (WT) or TNF−/− mice were transferred into RAG−/− or TNF−/− mice which were then infected with M. tuberculosis. Infected RAG−/− mice and RAG−/− recipients of TNF deficient T cells developed overwhelming infection, with extensive pulmonary and hepatic necrosis and succumbed with a median of only 16 days infection. By contrast, RAG−/− recipients of WT T cells showed a significant increase in survival with a median of 32 days. Although initial bacterial growth was similar in all groups of RAG−/− mice, the transfer of WT, but not TNF−/−, T cells led to the formation of discrete foci of leucocytes and macrophages and delayed the development of necrotizing pathology. To determine requirements for macrophage-derived TNF, WT or TNF−/− T cells were transferred into TNF−/− mice at the time of M. tuberculosis infection. Transfer of WT T cells significantly prolonged survival and reduced the early tissue necrosis evident in the TNF−/− mice, however, these mice eventually succumbed indicating that T cell-derived TNF alone is insufficient to control the infection. Therefore, both T cell- and macrophage-derived TNF play distinct roles in orchestrating the protective inflammatory response and enhancing survival during M. tuberculosis infection.

Keywords: TNF, T cells, mycobacteria, macrophage, granuloma

INTRODUCTION

The cytokine, TNF, is essential for generating and maintaining sustained protective immunity to mycobacterial infections. Gene deficient mice which lack TNF (TNF−/−) are highly susceptible to mycobacteria of both high and low virulence. Despite mounting an antigen-specific T cell response, TNF−/− mice are unable to control infection with strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis [1,2], M. avium[3] (Saunders, unpublished observation) and M. bovis BCG [4,5] (Saunders, unpublished observation). Administration of anti-TNF antibodies to mice chronically infected with M. tuberculosis leads to reactivation of latent infection [6]. Evidence from human studies also demonstrates an essential role for TNF in both the induction and maintenance of immunity to mycobacterial infection. A defect in TNF production was associated with the development of M. avium infection in a young child [7]. Further, several studies have now reported that individuals receiving anti-TNF therapy to treat Crohn's disease and rheumatoid arthritis show a significant increase in the reactivation of latent tuberculosis, often developing severe extrapulmonary disease [8,9]. Thus, sustained production of TNF is required to develop and maintain immunity to mycobacterial infections.

TNF is a multifunctional cytokine, that performs a variety of roles in both immune and inflammatory responses. At a cellular level TNF acts in synergy with IFN-γ to enhance the expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase and the antimycobacterial activity of infected macrophages [10]. TNF also induces apoptosis of leucocytes and the induction of apoptosis, but not necrosis, in mycobacteria-infected macrophages leads to the death of the internalized bacilli [11,12]. Some virulent strains of mycobacteria appear to survive in macrophages by evading TNF-induced apoptosis by stimulating the release of TNFRII which inactivates TNF [12,13]. At a tissue level TNF co-ordinates the inflammatory process, orchestrating the recruitment, migration and retention of cells to the site of infection or inflammation through the up-regulation of adhesion molecules on leucocytes and endothelial cells and increased expression of chemokines within infected tissue [14,15]. In particular, TNF is essential for the colocation of lymphocytes and macrophages within granulomas where their close apposition facilitates the activation of mycobacterial killing and prevents dissemination of the infection [2].

TNF is produced by an array of cell types, principally activated macrophages, however, T cells, dendritic cells and endothelial cells can also secrete TNF. Previously, endogenous TNF synthesis by mycobacteria-infected macrophages was shown to contribute to mycobacterial killing [10,16], however, the relative contributions of T cell- and macrophage-derived TNF to protective immunity has not been defined in vivo. We have addressed this by investigating the specific effect of T cells secreting TNF during infection with virulent M. tuberculosis in recombinase activating gene 1 (RAG−/−) and TNF deficient mice. This revealed that T cell-derived TNF was required for the formation of normal inflammatory granulomatous response and was essential, but not sufficient, for sustained protective immunity against M. tuberculosis infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice

Specific pathogen free, female C57BL/6 and RAG1−/− mice at 6–8 weeks of age were purchased from the Animal Research Centre (Perth, Australia) and maintained in the SPF animal facility. TNF gene deficient mice were generated and maintained in barrier isolation in the Centenary Institute Animal Facility, as previously described [17]. All experiments were performed with the permission of the Sydney University Animal Ethics Committee.

Experimental infection

M. tuberculosis (H37Rv) was cultured to mid-log phase in Proskeur Beck medium and stored in 10% glycerol at −70°C. Before infection bacteria were washed once and diluted in PBS. Where indicated, WT and TNF−/− mice were irradiated with 550 Rads prior to infection. Groups of mice were injected intravenously (i.v) with M. tuberculosis bacilli with or without 1 × 106 purified CD3+ T cells. At defined time points the bacterial load was determined in the spleen, liver and lung following homogenization and serial dilution of organ homogenates on Middlebrook 7H11 agar, and incubation at 37°C for two-three weeks.

T cell purification and phenotypic analysis

Single cell spleen suspensions were prepared by sieving homogenates through 200 µm mesh and resuspending the cells in culture medium containing RPMI with 10% foetal calf serum (CSL Bioscience, Melbourne, Australia) and 10−5m 2-mercapto-ethanol [12]. Splenocytes were enriched for T cells by passage through a nylon wool column. Enriched T cells were then purified by magnetic cell sorting with indirect microbeads according to the manufacturer's instructions (Miltenyi Biotec, Gladbach, Germany). Briefly, cells were first labelled with FITC-conjugated anti-CD4 and -CD8, then incubated with anti-FITC microbeads before positive selection using a separation column. Purification was confirmed by staining for leucocyte markers, CD3, CD4, CD8, MAC-1 and B220, using fluorescently labelled antibodies (Caltag) and analysis on a FACS Calibur. This procedure resulted in CD3+ T cell populations with purity greater than 98%. Leucocyte subpopulations in the spleens of infected mice were determined by staining for the following leucocyte markers, using fluorescently labelled antibodies enumerated on a FACS star; CD4, CD8, CD62, NK1·1, MAC-1, Gr-1, B220 (Caltag), CD44, CD45 (Pharmingen).

Histology

The liver and inflated lung sections were fixed with 10% neutral buffered formalin for at least two weeks prior to embedding in paraffin and sectioned at 4 µm. Sections were stained with haematoxylin and eosin.

Lymphocyte responses to mycobacterial antigens

Single cell suspensions of splenocytes from infected mice were prepared and distributed at 2 × 105 cells per well in 96 well plates. The cells were stimulated with Concanavalin A (Sigma) and incubated for 72 h at 37°C prior to collection of supernatant to measure IFN-γ production. Concentrations of IFN-γ in culture supernatants were determined by capture ELISA using a capture assay with Abs R4–6A2 and XMG.2 biotin (Endogen Woburn, MA, USA) following the manufacturer's instructions.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis of the results from immunological assays and log transformed bacterial counts were conducted using analysis of variance (Anova). Fisher's Protected Least Significant Difference Anova post hoc test was used for pair-wise comparison of multigrouped data sets. Differences with P < 0·05 were considered significant. Kaplan-Meier Survival analysis were used to calculate cumulative survival statistics. Log rank (Mantel-Cox) differences with P < 0·05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

TNF producing T cells increase the survival of M. tuberculosis-infected RAG−/− mice

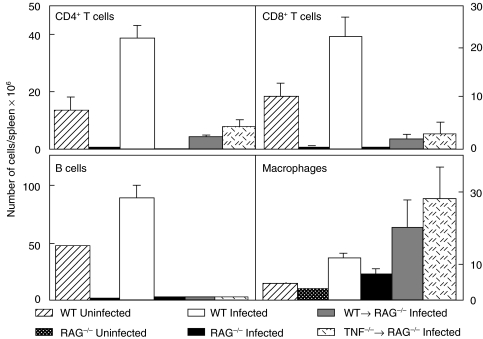

The role of T cell-derived TNF in the development of protective immunity was investigated using RAG−/− mice, which lack T and B cells, but possess TNF-producing macrophages. While TB infection in humans is usually via the respiratory tract, an intravenous model was used in these studies to allow rapid stimulation of adoptively transferred T cells. RAG−/− mice were injected with 106 purified CD3+ T cells from WT or TNF−/− mice and 106M. tuberculosis delivered by the intravenous route. At 14 days post infection both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were isolated from the spleens of RAG−/− recipients of either WT or TNF−/− T cells (Fig. 1). The number of T cells recovered from the spleen demonstrated that transferred cells survived and proliferated in vivo(Table 1). Interestingly, there was greater expansion of TNF-deficient T cells, than WT T cells, at day 16 post infection, though these cells produced similar IFN-γ responses to mitogen stimulation (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

TNF producing T cells proliferate in vivo. Purified CD3+ T cells (106/mouse) from WT and TNF−/− mice were transferred into RAG−/− mice who were then infected intravenously with 106 M. tuberculosis H37Rv. After 14 days infection spleens were removed, single cell suspensions were stained with fluorochrome labelled antibodies to CD4+, CD8+ T cells, B cell and macrophages, and cell populations were determined by FACS analysis. Data represent the mean and standard deviation of 5 mice/group in one of three separate experiments.

Table 1.

Total splenocyte numbers and IFNγ responses in RAG−/− recipients of WT or TNF−/− T cells

| T cell donor | Recipient* | Cell number† | IFNγ (pg/2 × 105 cells) |

|---|---|---|---|

| – | WT | 2·68 × 108 ± 4·5 × 107 | 5806 ± 370 |

| – | RAG−/− | 1·46 × 107 ± 1·0 × 106 | 168 ± 76 |

| WT | RAG−/− | 5·40 × 107 ± 2·42 × 107 | 4350 ± 2696 |

| TNF−/− | RAG−/− | 7·84 × 107 ± 7·5 × 106 | 6010 ± 1690 |

Recipient mice received 1 × 106 purified T cells and 1 × 106 M. tuberculosis H37Rv intravenously. Spleens were harvested 14 days later, and single cell suspensions were cultured at 2 × 105 splenocytes with ConA (10 µg/ml) for 72 h before IFNγ levels were measured by ELISA.

Cell numbers in uninfected mice: WT, 7·30 × 107 ± 2·5 × 107, RAG−/−, 6·34 × 106 ± 4·3 × 106. Data represent the means and standard deviations of 5 mice per group, in one of three representative experiments.

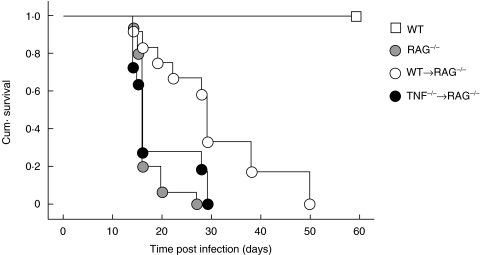

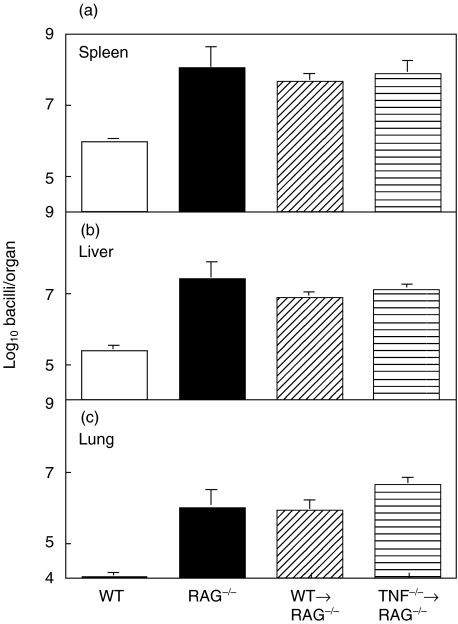

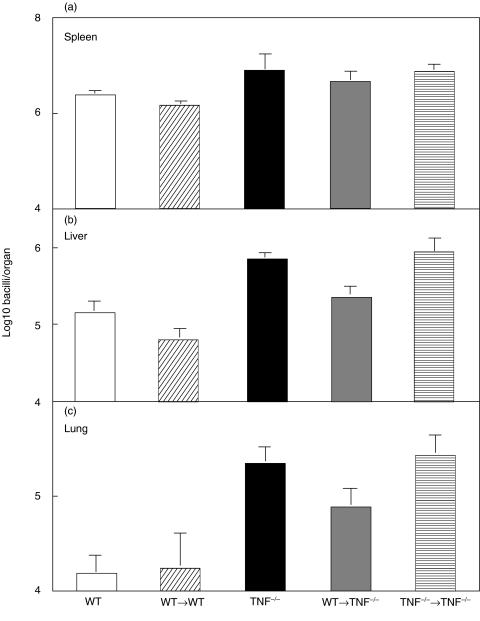

Normal RAG−/− mice were unable to control M. tuberculosis infection and became moribund, with a median time of 16 days post infection (Fig. 2). Although transferred T cells survived and proliferated in vivo, only the transfer of T cells from WT, and not TNF−/− mice significantly enhanced the survival of infected RAG−/− mice in three independent experiments (P < 0·001) (Fig. 2). The median survival time for recipients of WT T cells was 32 days compared with a median survival of recipients of TNF−/− T cells of only 16 days. This prolonged survival was not due to differences in mycobacterial growth (Fig. 3). RAG−/− mice, regardless of the transferred T cells, showed increased M. tuberculosis replication compared to immunocompetent WT mice at 16 days post infection (Fig. 3). Indeed, the bacterial load in recipients of WT and TNF−/− T cells was similar to that in unreconstituted RAG−/− mice.

Fig. 2.

TNF producing T cells enhance survival of M. tuberculosis infected RAG−/− mice. Purified CD3+ T cells (106/mouse) from WT and TNF−/− mice were transferred into RAG−/− mice who were then infected intravenously with 106 M. tuberculosis H37Rv. Transfer of T cells from WT, but not TNF deficient, mice into RAG−/− recipients significantly enhanced their survival (n = 10–15 mice/group), Logrank (Mantel-Cox) P < 0·001. Data is representative of one of three separate experiments.

Fig. 3.

Transfer of TNF producing T cells does not reduce the growth of M. tuberculosis within RAG−/− mice. Purified CD3+ T cells (106/mouse) from WT and TNF−/− mice were transferred into RAG−/− mice who were then infected intravenously with 106 M. tuberculosis H37Rv. Growth of M. tuberculosis in (a) the spleen, (b) the liver and (c) the lung at 14 days post infection. Data represent the means and standard deviations of 5 mice/group, in one of three representative experiments.

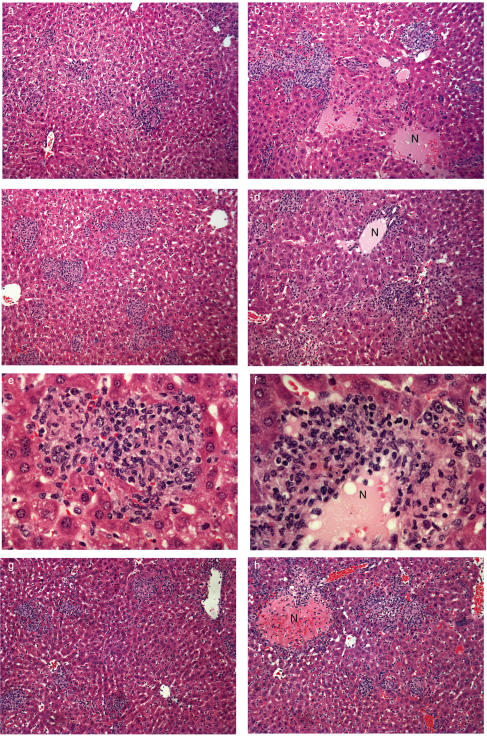

T cell-derived TNF is required for granuloma formation in RAG−/− mice

Although bacterial growth was unaffected by the transfer of T cells into RAG−/− mice, the transfer of TNF sufficient, WT T cells contributed to the formation of a granulomatous inflammatory response which partially contained the infection. (Fig. 4). At 14 days post infection, the livers of immunocompetent WT mice contained a few small discrete foci composed of macrophages and lymphocytes (Fig. 4a). The livers of the unreconstituted RAG−/− mice, however, contained large areas of necrosis and cell degradation. Pockets of neutrophils were seen throughout the liver along with macrophages and apoptotic bodies (Fig. 4b). In contrast, livers of RAG−/− recipients of T cells from WT mice displayed discrete cellular foci, similar in organization to the foci seen in the livers of WT mice (Fig. 4c), although these lesions were larger in size and number. There were lymphocytes and macrophages with occasional neutrophils (Fig. 4e) and strikingly less necrosis than in the unreconstituted RAG−/− mice (Fig. 4b). By contrast, the transfer of T cells from TNF−/− mice into RAG−/− recipients was not associated with discrete foci formation and the livers of these mice were of similar appearance to those in the untreated RAG−/− mice (Fig. 4d). They contained large areas of necrosis with pockets of neutrophils spread throughout the tissue. Some lymphocytes and macrophages were present in the livers, but these cells failed to localize and form discrete lesions (Fig. 4f). These data indicate that TNF synthesis by macrophages in229.0 pt RAG−/− mice was not sufficient to permit organization of donor TNF-deficient T cells into effective granulomas. Therefore both macrophage- and T cell-derived TNF is required for this process.

Fig. 4.

Transfer of TNF producing T cells contributes to the formation of protective granulomatous lesions. (a–f) Livers from RAG−/− mice, 14 days post T cell transfer and M. tuberculosis infection, were fixed in formalin and H&E stained. (a) WT mice, note the small, compact discrete lesions composed of lymphocytes and macrophages. (b) RAG−/− mice, lesions are large and diffuse, extensive necrosis was seen throughout the liver (N). (c, e) WT → RAG−/− mice, lesions are larger and more diffuse than those seen on WT mice but they are more compact and show less necrosis than RAG−/− mice. (d, f) TNF−/− → RAG−/− mice, lesions are large, diffuse with large areas of necrotic tissue (N) visible throughout the liver. Image is a representative section of one of 15 livers from three separate experiments. (g, h) Livers from irradiated TNF−/− mice 21 days after the transfer of purified T-cells and M. tuberculosis infection. (g) WT → TNF−/− mice; lesions are small and compact, composed of lymphocytes and macrophages, occasional small areas of necrosis were noted. (h) TNF−/− → TNF−/− mice; lesions are large and diffuse with areas of necrosis (N) throughout the liver. Each image is a representative section of one of 15 livers from three separate experiments.

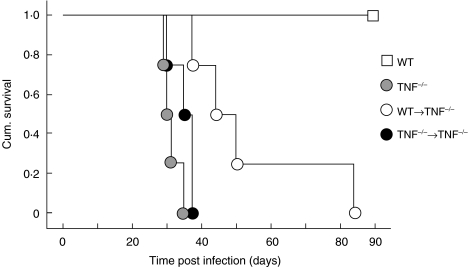

T cell-derived TNF increases the survival of M. tuberculosis-infected TNF−/− mice

To determine if T cell-derived TNF alone was sufficient to control M. tuberculosis infection, T cells from WT and TNF−/− mice were transferred into irradiated TNF−/− mice at the time of M. tuberculosis infection. Irradiation alone did not significantly alter survival of infected TNF−/− mice (Fig. 5). The transfer of WT, but not TNF−/−, T cells significantly increased the survival of TNF−/− mice following M. tuberculosis infection in three separate experiments (P < 0·006) (Fig. 5). The mean survival time in recipients of WT T cells was 53 days compared with 31 days for the recipients of TNF−/− T cells. Bacterial load was significantly reduced in the livers of the TNF−/− recipients of WT T cells at day 21, as compared to the recipients of TNF−/− T cells (Fig. 6), though the extent of T cell activation following infection was similar among all groups of infected mice (data not shown).

Fig. 5.

T cell derived TNF contributes to survival of M. tuberculosis infected mice. WT and TNF−/− mice were irradiated with 550 Rads 24 h prior to the transfer of purified CD3+ T cells (106/mouse) from WT and TNF−/− mice and intravenous infection with 104M. tuberculosis H37Rv. The transfer of WT T cells into TNF−/− mice significantly enhanced the survival of these animals compared to TNF−/− mice receiving T cells from TNF−/− mice (n = 4–7 mice/group) Logrank (Mantel-Cox) P < 0·006. Data is representative of one of three separate experiments.

Fig. 6.

T cell derived TNF contributes to containment of bacterial growth in the liver of TNF−/− mice. Transfer of WT T cells into TNF−/− mice, as described in Fig. 5, led to a significant, small, reduction in bacterial growth in the liver (b) (P < 0·05 Anova) but did not significantly affect growth in (a) the spleen or (c) the lung. Data represent the means and standard errors of 5 mice per group from one of three experiments.

T cell-derived TNF delays necrotizing pathology in TNF−/− mice

The most striking difference in the TNF−/− recipients of WT T cells, compared to other TNF−/− infected mice, was the pattern of the inflammatory response in the liver (Fig. 4g,h). WT mice formed the characteristic compact lesions containing macrophages and lymphocytes as previously described [2], and irradiated WT mice developed similar lesions (data not shown). At 21 days post infection, TNF−/− mice showed a delay in cell influx as compared to the WT mice. The infiltrating leucocytes were loosely associated, with large numbers of neutrophils and extensive areas of necrosis, affecting the majority of the liver [2]. The transfer of WT, but not TNF−/−, T cells into the TNF−/− mice increased the number of leucocytes in the liver at three weeks post infection. The lesions formed were more compact with less necrosis and neutrophil infiltration, and resembled the lesions in WT rather than TNF−/− mice (Fig. 4g). This was associated with prolonged survival. In TNF−/− recipients of TNF−/− T cells there was a diffuse influx of macrophages and lymphocytes which did not form compact lesions (Fig. 4h). Taken together with survival data (Fig. 5) this indicates that T cell-derived TNF is associated with partial granuloma formation and containment of infection.

DISCUSSION

TNF is essential for resistance to M. tuberculosis in both mice and humans [1,2,7,8]. Studies in TNF deficient mice and the clinical use of TNF neutralizing antibodies in humans demonstrated that TNF is essential for maintaining granulomas and preventing bacterial replication. While the critical role for TNF is clear, the cellular source of TNF involved in protective immunity remained undefined. This study demonstrates that both T cell- and macrophage-derived TNF contribute to protective immunity against M. tuberculosis infection. The transfer of WT, but not TNF deficient, T cells into RAG−/− and TNF−/− mice infected with M. tuberculosis increased survival in both groups. The failure of TNF−/− T cells to protect the RAG mice was not due to the loss of the transferred T cells. On the contrary, these cells proliferated extensively in vivo. From the initial inoculum of 106 T cells, over five times that number of T cells were isolated from the spleens of all recipient RAG mice. Moreover, recipients of TNF−/− T cells had higher numbers of T cells in their spleens than recipients of WT T cells. The reasons for the enhanced expansion of T cells from TNF−/− mice compared with WT mice are not clear. The bacterial loads were equivalent in both groups of mice at day 14, so increased antigenic stimulus for T cell proliferation was not the likely cause. TNF binding to the TNFR1 activates the death domain of that receptor resulting in the apoptosis of targeted cells [13,18,19], and possibly T cell-derived TNF may contribute to T cell apoptosis during the cellular response to M. tuberculosis.

Macrophages are an important source of TNF, and signalling through TNFRI and TNFRII stimulates an array of macrophage activities. TNF synergises with IFN-γ to activate antimycobacterial properties of macrophages [10,16]. TNF up-regulates reactive oxygen and nitrogen intermediates, increases NFκB expression and contributes to the recruitment, migration and retention of inflammatory cells at the site of infection [10,16,20]. Determining the cellular source of TNF in humans is difficult. T cell production of TNF, has been documented with both human [21,22] and murine [23] T cells. The majority of T cell clones isolated from leprosy patients displayed a Th0-like phenotype with IFN-γ, TNF, IL-10, IL-2 and IL-5 production, although a minority had a Th1 phenotype secreting IFN-γ, TNF and IL-2 [21]. Further, supernatants from human T cell clones, in combination with granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulated factor, induced aggregation of macrophages, and this effect was abrogated by antibodies to TNF [22]. These findings support our conclusion that TNF from T cells may be an important contributor to granuloma formation which is an integral part of resistance to mycobacterial infection.

During mycobacterial infection in immunocompetent mice, T cells and monocytes migrate to sites of infection initiating the close juxtaposition of T cells and macrophages necessary for macrophage activation. In TNF−/− mice, initial cell recruitment is delayed and the T cells eventually recruited are unable to migrate through the tissue to the infected macrophages and form discrete granulomas [2,20]. TNF−/− recipients of WT T cells displayed an intermediate phenotype in which early granulomas were smaller and more compact than those seen in TNF−/− mice, but larger than those in WT mice. This partial granuloma formation was associated with a survival advantage, even though bacterial loads were not reduced.

The marked tissue destruction in the absence of TNF signalling may occur through a number of mechanisms. Early recruitment of neutrophils is a feature of infected TNF−/− mice and this contributes to necrosis in lung tissues. Ehlers et al. [24] found that the severe necrosis occurring in TNFRp55 deficient mice infected with M. avium was inhibited, at least temporarily, by depletion of either CD4 or CD8 T cells. These authors suggested that in the absence of TNF signalling, T cell recruitment induced apoptosis of inflammatory cells leading to granuloma disintegration [24]. By contrast, we show that, the early transfer of WT T cells to the TNF deficient mice delayed the development of destructive pathology suggesting that T cell-derived TNF contributes to an inflammatory response, recruiting lymphocytes and macrophages, that partially controls the infection.

TNF is involved at multiple points in cell migration and granuloma formation. It up-regulates adhesion molecules, such as ICAM-1, VCAM-1 and E-selectin [25] to facilitate the tethering and diapedesis of leucocytes through the endothelium into infected tissue. Cell recruitment was clearly delayed in TNF−/− mice, although eventually it reached similar levels to those in WT infected mice [2,20]. Thus, early cell migration is dependent upon TNF. TNF is also involved in chemokine induction and interacts with the extracellular matrix (ECM) to direct T cell migration [26–28]. Further, TNF signalling through TNFRII delivers a ‘stop’ signal for T cells that is independent of any changes in the expression of chemokine receptors or β1 integrins [15,27,28]. TNF−/− mice infected with mycobacteria show delayed induction in multiple chemokines [20] and recently we have found that chemokine receptor expression is also reduced in TNF deficient mice during M. bovis BCG infection (Saunders, unpublished observations). The current study suggests that T cell-derived TNF contributes to T cell navigation through the ECM to the site of infection. T cells adhere to ECM glycoproteins, secrete degradative enzymes and orientate themselves in response to cytokine and chemokine signals, many of which are influenced by the expression of TNF [14,15]. In this way, T cell-derived TNF can play an essential function in coordinating granuloma formation and in generating a protective immune response to M. tuberculosis infection.

The transfer of TNF−/− T cells to RAG recipients did not enhance immunity to M. tuberculosis, despite the TNF production in their nonlymphoid cells. Thus, soluble TNF secreted by macrophages in RAG−/− mice was not sufficient to initiate effective cell migration. TNF is synthesized as a transmembrane precursor that is cleaved by membrane-bound metalloproteases forming the membrane-bound or soluble cytokine [29,30]. The unique functions of soluble and membrane bound TNF have not been well characterized. A recent study using TNF/lymphotoxin double knockout mice reconstituted with the gene for membrane-bound TNF (membrane TNF knock-in mice) suggests that both soluble and membrane-bound TNF contribute to control of M. bovis BCG infection [31]. Thus, one explanation for the failure of TNF−/− T cells to migrate as efficiently as cells capable of secreting TNF is that T cell migration requires membrane-bound TNF on the T cell. This form of TNF may interact directly with the ECM to facilitate adhesion, migration and tethering of the T cell. Membrane TNF can initiate a signal in the TNF–expressing cell following interaction with either soluble or cell-bound TNFR [32]. This ‘reverse signalling’ modulates anti-CD3-triggered T cell cytokine expression in mice and humans [32–34]. Studies are currently underway to explore the function of membrane TNF in M. tuberculosis infection. In conclusion, this study has established that both T cell- and macrophage-derived TNF are required for the co-ordinated inflammatory response to contain M. tuberculosis infection.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia and the New South Wales Department of Health through its research infrastructure grant to the Centenary Institute of Cancer Medicine and Cell Biology. The expert technical assistance of Meera Karunakaran is gratefully acknowledged.

REFERENCES

- 1.Flynn JL, Goldstein MM, Chan J, et al. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha is required in the protective immune response against Mycobacterium tuberculosis in mice. Immunity. 1995;2:561–72. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90001-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bean AG, Roach DR, Briscoe H, France MP, Korner H, Sedgwick JD, Britton WJ. Structural deficiencies in granuloma formation in TNF gene-targeted mice underlie the heightened susceptibility to aerosol Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection, which is not compensated for by lymphotoxin. J Immunol. 1999;162:3504–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ehlers S, Benini J, Kutsch S, Endres R, Rietschel ET, Pfeffer K. Fatal granuloma necrosis without exacerbated mycobacterial growth in tumor necrosis factor receptor p55 gene-deficient mice intravenously infected with Mycobacterium avium. Infect Immun. 1999;67:3571–9. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.7.3571-3579.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jacobs M, Marino MW, Brown N, Abel B, Bekker LG, Quesniaux VJ, Fick L, Ryffel B. Correction of defective host response to Mycobacterium bovis BCG infection in TNF-deficient mice by bone marrow transplantation. Laboratory Invest. 2000;80:901–14. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3780094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bopst M, Garcia I, Guler R, et al. Differential effects of TNF and LTalpha in the host defense against M. Bovis BCG. Eur J Immunol. 2001;31:1935–43. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200106)31:6<1935::aid-immu1935>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mohan VP, Scanga CA, Yu K, et al. Effects of tumor necrosis factor alpha on host immune response in chronic persistent tuberculosis: possible role for limiting pathology. Infect Immun. 2001;69:1847–55. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.3.1847-1855.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tuerlinckx D, Vermylen C, Brichard B, Ninane J, Cornu G. Disseminated Mycobacterium Avium Infection in a Child with Decreased Tumour Necrosis Factor Production. Eur J Ped. 1997;156:204–6. doi: 10.1007/s004310050583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Keane J, Gershon S, Wise RP, Mirabile-Levens E, Kasznica J, Schwieterman WD, Siegel JN, Braun MM. Tuberculosis associated with infliximab, a tumor necrosis factor alpha-neutralizing agent. New Eng J Med. 2001;345:1098–104. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roth S, Delmont E, Heudier P, et al. Anti-TNF alpha monoclonal antibodies [infliximab] and tuberculosis: apropos of three cases. Rev Intern Med. 2002;23:312–6. doi: 10.1016/s0248-8663(01)00556-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schaible UE, Collins HL, Kaufmann SH. Confrontation between intracellular bacteria and the immune system. Adv Immunol. 1999;71:267–377. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60405-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Molloy A, Laochumroonvorapong P, Kaplan G. Apoptosis, but not necrosis, of infected monocytes is coupled with killing of intracellular bacillus Calmette-Guerin. J Exp Med. 1994;180:1499–509. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.4.1499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rojas M, Olivier M, Gros P, Barrera LF, Garcia LF. TNF-alpha and IL-10 modulate the induction of apoptosis by virulent Mycobacterium tuberculosis in murine macrophages. J Immunol. 1999;162:6122–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Balcewicz-Sablinska MK, Keane J, Kornfeld H, Remold HG. Pathogenic Mycobacterium tuberculosis evades apoptosis of host macrophages by release of TNF-R2, resulting in inactivation of TNF-alpha. J Immunol. 1998;161:2636–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McDermott MF. TNF and TNFR biology in health and disease. Cell Molec Biol. 2000;47:619–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Franitza S, Hershkoviz R, Kam N, Lichtenstein N, Vaday GG, Alon R, Lider O. TNF-alpha associated with extracellular matrix fibronectin provides a stop signal for chemotactically migrating T cells. J Immunol. 2000;165:2738–47. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.5.2738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Britton WJ, Meadows N, Rathjen DA, Roach DR, Briscoe H. A tumor necrosis factor mimetic peptide activates a murine macrophage cell line to inhibit mycobacterial growth in a nitric oxide-dependent fashion. Infect Immun. 1998;66:2122–7. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.5.2122-2127.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Korner H, Riminton DS, Strickland DH, Lemckert FA, Pollard JD, Sedgwick JD. Critical points of tumor necrosis factor action in central nervous system autoimmune inflammation defined by gene targeting. J Exp Med. 1997;186:1585–90. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.9.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Balcewicz-Sablinska MK, Gan H, Remold HG. Interleukin 10 produced by macrophages inoculated with Mycobacterium avium attenuates mycobacteria-induced apoptosis by reduction of TNF-alpha activity. J Infect Dis. 1999;180:1230–7. doi: 10.1086/315011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fratazzi C, Arbeit RD, Carini C, Balcewicz-Sablinska MK, Keane J, Kornfeld H, Remold HG. Macrophage apoptosis in mycobacterial infections. J Leuk Biol. 1999;66:763–4. doi: 10.1002/jlb.66.5.763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roach DR, Bean AG, Demangel C, France MP, Briscoe H, Britton WJ. TNF regulates chemokine induction essential for cell recruitment, granuloma formation, and clearance of mycobacterial infection. J Immunol. 2002;168:4620–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.9.4620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barnes PF, Abrams JS, Lu S, Sieling PA, Rea TH, Modlin RL. Patterns of cytokine production by mycobacterium-reactive human T-cell clones. Infect Immun. 1993;61:197–203. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.1.197-203.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Verhagen CE, van der Pouw Kraan TC, Buffing AA, Chand MA, Faber WR, Aarden LA, Das PK. Type 1- and type 2-like lesional skin-derived Mycobacterium leprae-responsive T cell clones are characterized by coexpression of IFN-gamma/TNF-alpha and IL-4/IL-5/IL-13 respectively. J Immunol. 1998;160:2380–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Firestein GS, Roeder WD, Laxer JA, et al. A new murine CD4+ T cell subset with an unrestricted cytokine profile. J Immunol. 1989;143:518–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ehlers S, Kutsch S, Ehlers EM, Benini J. Pfeffer K. Lethal granuloma disintegration in mycobacteria-infected TNFRp55 (−/−) mice is dependent on T Cells IL-12. J Immunol. 2000;165:483–92. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.1.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Madge LA, Pober JS. TNF signaling in vascular endothelial cells. Exp Molec Path. 2001;70:317–25. doi: 10.1006/exmp.2001.2368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Czermak BJ, Sarma V, Bless NM, Schmal H, Friedl HP, Ward PA. In vitro and in vivo dependency of chemokine generation on C5a and TNF-alpha. J Immunol. 1999;162:2321–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vaday GG, Hershkoviz R, Rahat MA, Lahat N, Cahalon L, Lider O. Fibronectin-bound TNF-alpha stimulates monocyte matrix metalloproteinase-9 expression and regulates chemotaxis. J Leuk Biol. 2000;68:737–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vaday GG. Combinatorial signals by inflammatory cytokines and chemokines mediate leukocyte interactions with extracellular matrix. J Leuk Biol. 2001;69:885–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Black RA, Rauch CT, Kozlosky CJ, et al. A metalloproteinase disintegrin that releases tumour-necrosis factor-alpha from cells. Nature. 1997;385:729–33. doi: 10.1038/385729a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moss ML, Jin SL, Milla ME, et al. Cloning of a disintegrin metalloproteinase that processes precursor tumour-necrosis factor-alpha. Nature. 1997;385:733–6. doi: 10.1038/385733a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Olleros ML, Guler R, Corazza N, et al. Transmembrane TNF induces an efficient cell-mediated immunity and resistance to Mycobacterium bovis bacillus Calmette-Guerin infection in the absence of secreted TNF and lymphotoxin-alpha. J Immunol. 2002;168:3394–401. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.7.3394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harashima S, Horiuchi T, Hatta N, et al. Outside-to-inside signal through the membrane TNF-alpha induces E-selectin (CD62E) expression on activated human CD4+ T cells. J Immunol. 2001;166:130–6. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.1.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ferran C, Dautry F, Merite S, Sheehan K, Schreiber R, Grau G, Bach JF, Chatenoud L. Anti-tumor necrosis factor modulates anti-CD3-triggered T cell cytokine gene expression in vivo. J Clin Invest. 1994;93:2189–96. doi: 10.1172/JCI117215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Higuchi M, Nagasawa K, Horiuchi T, Oike M, Ito Y, Yasukawa M, Niho Y. Membrane tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha) expressed on HTLV-I-infected T cells mediates a costimulatory signal for B cell activation – characterization of membrane TNF-alpha. Clin Immunol Immunopath. 1997;82:133–40. doi: 10.1006/clin.1996.4291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]