Abstract

We examined the role of osteoprotegerin (OPG) on tumour necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL)-induced apoptosis in rheumatoid fibroblast-like synovial cells (FLS). OPG protein concentrations in synovial fluid from patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) correlated with those of interleukin (IL)-1β or IL-6. A similar correlation was present between IL-1β and IL-6 concentrations. Rheumatoid FLS in vitro expressed both death domain-containing receptors [death receptor 4 (DR4) and DR5] and decoy receptors [decoy receptor 1 (DcR1) and DcR2]. DR4 expression on FLS was weak compared with the expression of DR5, DcR1 and DcR2. Recombinant TRAIL (rTRAIL) rapidly induced apoptosis of FLS. DR5 as well as DR4 were functional with regard to TRAIL-mediated apoptosis induction in FLS; however, DR5 appeared be more efficient than DR4. In addition to soluble DR5 (sDR5) and sDR4, OPG administration significantly inhibited TRAIL-induced apoptogenic activity. OPG was identified in the culture supernatants of FLS, and its concentration increased significantly by the addition of IL-1β in a time-dependent manner. Neither IL-6 nor tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α increased the production of OPG from FLS. TRAIL-induced apoptogenic activity towards FLS was reduced when rTRAIL was added without exchanging the culture media, and this was particularly noticeable in the IL-1β-stimulated FLS culture; however, the sensitivity of FLS to TRAIL-induced apoptosis itself was not changed by IL-1β. Interestingly, neutralization of endogenous OPG by adding anti-OPG monoclonal antibody (MoAb) to FLS culture restored TRAIL-mediated apoptosis. Our data demonstrate that OPG is an endogenous decoy receptor for TRAIL-induced apoptosis of FLS. In addition, IL-1β seems to promote the growth of rheumatoid synovial tissues through stimulation of OPG production, which interferes with TRAIL death signals in a competitive manner.

Keywords: fibroblast-like synovial cells, IL-1β, OPG, rheumatoid arthritis, TRAIL

INTRODUCTION

The soluble receptor, osteoprotegerin (OPG), is a member of the tumour necrosis factor receptor (TNFR) superfamily and acts as a receptor antagonist. The decoy function of OPG towards receptor activator of nuclear factor κB ligand (RANKL) is well recognized; OPG binds RANKL, and thus prevents the interaction with, and stimulation of, RANK [1–3]. Hence, OPG inhibits osteoclast differentiation and survival as demonstrated both in vivo and in vitro[4]. OPG is also thought to be involved in inflammatory diseases based on results of experimental studies demonstrating stimulation of OPG production from endothelial cells by tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α and interleukin (IL)-1β[5]. Furthermore, OPG has also been shown to exhibit mitogenic and/or anti-apoptotic properties for foreskin fibroblasts and/or endothelial cells [6,7].

Marked hyperplasia of synovial tissues is a characteristic feature of rheumatoid arthritis (RA), which is mediated, at least in part, by impaired apoptosis of synovial cells in situ[8]. The anti-apoptotic feature of rheumatoid synovial cells in situ may not be intrinsic, but rather develop in the inflammatory rheumatoid microenvironment. In this regard, we have demonstrated that the sensitivity of fibroblast-like synovial cells (FLS) to apoptogenic stimuli is modulated by various inflammatory cytokines [9–11]. OPG acts also as a receptor antagonist for TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) [12]. We have shown recently that FLS are sensitive toward TRAIL-mediated apoptosis [13]. TRAIL triggers the activation of caspase-8 in FLS, which induces mitochondrial perturbation [13]. As both mitochondrial perturbation and DNA fragmentation were completely inhibited by caspase-8 inhibitor, FLS are classed into type II cell death in response to TRAIL [13]. The regulatory mechanisms of inflammatory cytokines on OPG production may influence TRAIL-induced apoptosis of synovial cells, and thus defines a new functional role for OPG in the pathological process of RA.

In the present study, we demonstrate that IL-1β in rheumatoid synovial fluid is the major inflammatory cytokine responsible for stimulation of OPG synthesis from FLS. Furthermore, our data suggest that OPG produced by FLS is an endogenous receptor antagonist of TRAIL-induced apoptosis in FLS which may, in part, explain the growth-promoting activity of IL-1β for rheumatoid synovial tissues.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Determination of OPG, IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α concentrations in synovial fluid from patients with RA

Synovial fluid samples were obtained from patients with RA, who fulfilled the criteria of the American Rheumatism Association for RA [14], admitted to the National Ureshino Hospital (28 synovial fluid samples from 28 RA patients). The experimental protocol was approved by the Hospital Human Ethics Review Committee and signed consent was obtained from each patient. The concentrations of OPG, IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α in the rheumatoid synovial fluid were examined by a sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (OPG; Immunodiagnostik AC, Bensheim, Germany: IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α; Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Tokushima, Japan). In brief, the plates precoated with monoclonal antibody (MoAb) against OPG, IL-1β, IL-6 or TNF-α were incubated with the samples, incubated further with the secondary antibody, and colour was developed according to the protocol provided by the supplier.

Effect of inflammatory cytokines on OPG production from cultured FLS

FLS were isolated from 20 patients with RA at the time of orthopaedic surgery (total knee replacement) conducted at National Ureshino Hospital. Signed consent was also obtained from each patient. Briefly, the synovial tissues were trimmed of fat and minced with scissors, then added to a mixture of collagenase (Sigma Chemical Co., St Louis, MO, USA) and dispase (Godo Shusei Co., Tokyo). The tissue mixture was digested over a 45-min period during gentle stirring at 37°C, and the harvested cells were allowed to adhere to Petri dishes (Falcon 3003, Becton Dickinson Co., Oxnard, CA, USA). The adherent cells used in the present study at third to fifth passages were less than 1% reactive with various MoAbs, including CD3, CD68, CD20 and von-Willebrand factor, which define FLS. Isolated FLS were cultured in the presence or absence of recombinant IL-1β (rIL-1β, Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., 20 IU/ml), rIL-6 plus r-soluble IL-6 receptor (sIL-6R) (R&D Systems Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA, 100 ng/ml each) or rTNF-α (R&D Systems, 200 IU/ml) for indicated time intervals in RPMI-1640 containing 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) (1 × 105/35 mm dish). OPG protein concentration in the culture supernatants was examined by the sandwich ELISA as described above.

Expression of TRAIL receptors on cultured FLS

Expression of TRAIL receptors on cultured rheumatoid FLS was examined by flow cytometric analysis. Treated FLS were detached by addition of 0·265 mm EDTA, washed with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and incubated with antihuman death receptor 4 (DR4; R&D Systems), antihuman DR5 (R&D Systems), antihuman decoy receptor 1 (DcR1; R&D Systems) or antihuman DcR2 (R&D Systems) at 4°C for 30 min. After incubation, the cells were washed with PBS, incubated further with phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated antigout IgG (Sigma Chemical Co.), and the expression of DR4, DR5, DcR1 and DcR2 was examined by flowcytometer (Epics XL, Beckman Coulter, Hialeah, FL, USA).

Effect of OPG toward TRAIL-induced apoptosis of cultured FLS

We have shown recently that cultured FLS are committed to type II cell death in response to TRAIL [13], thus disruption of mitochondrial transmembrane potential (ΔΨm) was used to quantify TRAIL-mediated FLS apoptosis in the present study. FLS were cultured in the presence or absence of various cytokines for indicated hours, washed, and incubated further with varying concentrations of rTRAIL (R&D Systems) with or without rOPG (R&D Systems), soluble DR4 (sDR4; R&D Systems) or sDR5 (R&D Systems) for an additional 2 h. After incubation, ΔΨm was examined as described recently [13]. In brief, treated FLS were detached by adding 0·265 mm EDTA, washed, and incubated further with a saturating amount of DiOC6 (3,3′-dihexyloxacarbocyamine iodide, Fluoreszenztechnologie, Grottenhofstr, Austria) at 37°C for 15 min. After incubation, the percentage of ΔΨm in FLS was quantified by flow cytometer (Epics XL, Beckman Coulter).In some experiments, rTRAIL was added to FLS culture without exchanging the culture media, and TRAIL-induced apoptosis in FLS was also examined by ΔΨm. To neutralize endogenous OPG secreted from FLS in culture, anti-OPG MoAb (mouse IgG1; R&D Systems) was added, and TRAIL-mediated apoptosis in FLS was examined by ΔΨm.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the Student's t-test or Spearman's rank correlation analysis. P-values <0·05 were selected as the level of significance.

RESULTS

Determination of OPG protein in synovial fluid of patients with RA

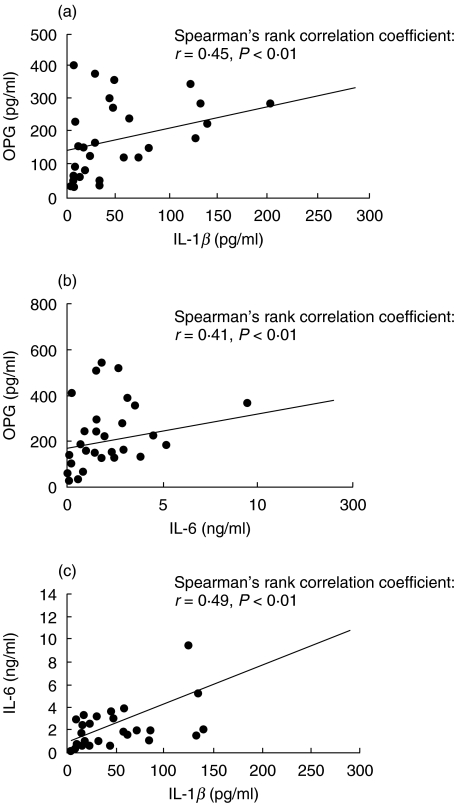

First, we examined whether OPG protein was present in the rheumatoid synovial fluid. As reported recently [15,16], OPG protein was detected in all samples examined, although the level varied from one sample to another (Fig. 1a). Furthermore, there was a positive correlation between the concentrations of OPG and IL-1β. In addition, a similar correlation was demonstrated between the protein concentration of OPG and IL-6, and between that of IL-1β and IL-6 (Fig. 1b,c). In contrast, TNF-α was detected in only a proportion of the samples, and the levels of this cytokine did not correlate with OPG concentration (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

Positive correlation of protein concentration between OPG and IL-1β (a), OPG and IL-6 (b) and IL-1β and IL-6 (c) found in synovial fluid samples (total 27 synovial fluids examined) of RA patients.

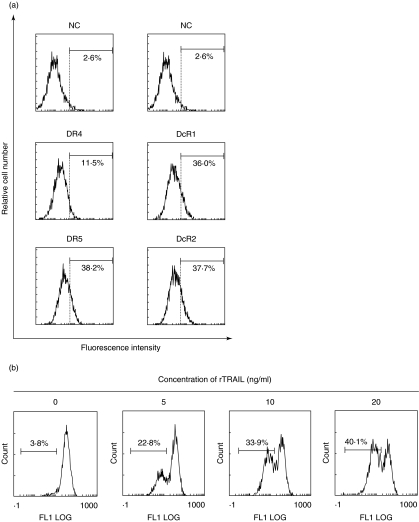

TRAIL induces apoptosis in FLS through DR4 and DR5

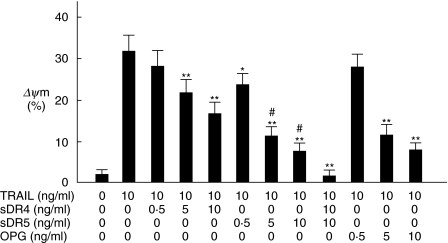

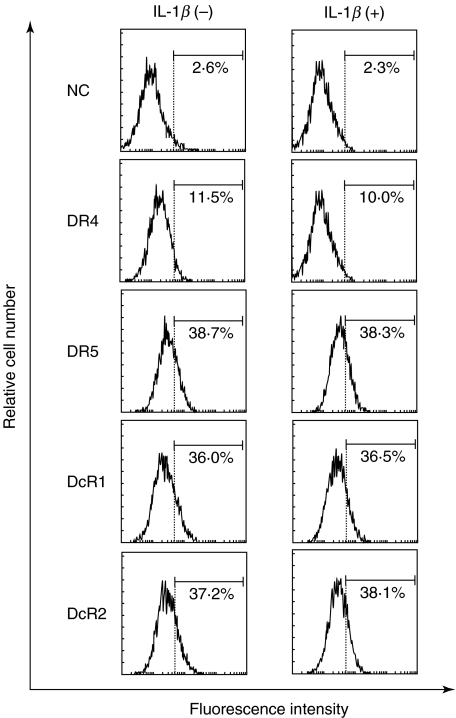

As shown in Fig. 2a, rheumatoid FLS in vitro expressed DR4, DR5, DcR1 and DcR2. Expression of DR4 was not so obvious compared with DR5, DcR1 and DcR2. Figure 2B shows that rTRAIL induced apoptotic cell death in FLS in a dose-dependent manner. To clarify the functional role of DR4 and DR5 in TRAIL-mediated apoptosis in FLS, we performed the blocking experiments by the use of sDR4 and sDR5. sDR4 interferes with the interaction between TRAIL and DR4, and sDR5 interferes with that between TRAIL and DR5. As shown in Fig. 3, TRAIL-induced ΔΨm in FLS was inhibited partially by sDR4 or sDR5, whereas it was inhibited completely by adding both sDR4 and sDR5. DR5 on FLS was suggested to be more functional to induce TRAIL-mediated apoptosis compared with DR4 (Fig. 3). In addition, OPG administration significantly suppressed TRAIL-mediated apoptosis in FLS (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

TRAIL-mediated apoptosis in FLS by rTRAIL. (a) Expression of TRAIL receptors on FLS. Rheumatoid FLS were detached by adding EDTA, reacted with anti-DR4, anti-DR5, anti-DcR1 or anti-DcR2 at 4°C for 30 min, and incubated further with PE-conjugated antigout IgG at 4°C for 30 min. After incubation, surface expression of DR4, DR5, DcR1 and DcR2 on FLS was examined by flow cytometer as described in the text. Note that FLS expressed DR4, DR5, DcR1 and DcR2; however, DR4 expression was weak compared with the other three receptors. NC; negative control, stained with goat IgG instead of first antibody. Numbers are the percentage of positive cells. Results are representative data from five individual samples. (b) Quantification of TRAIL-mediated apoptosis in FLS by ΔΨm. FLS were incubated with varying concentrations of rTRAIL for 2 h, detached by adding 0·265 mm EDTA, and ΔΨm was quantified as described in the text. Note that rTRAIL induced ΔΨm in FLS in a dose-dependent manner. Numbers are the percentage of positive cells. Results are representative data from five individual samples.

Fig. 3.

Inhibition of TRAIL-mediated apoptosis in FLS by sDR4, sDR5 and OPG. FLS were cultured with 10 ng/ml of rTRAIL in the presence of varying concentrations of sDR4, SDR5 or OPG for 2 h. After incubation, apoptosis of FLS was quantified by ΔΨm as described in the text. Note that TRAIL-mediated apoptosis in FLS was suppressed by sDR4, sDR5 and OPG; however, the inhibition was not complete. TRAIL-mediated apoptosis in FLS was inhibited completely by administration of both sDR4 and sDR5. *P < 0·05 versus FLS cultured with rTRAIL. **P < 0·01 versus FLS treated with rTRAIL. #P < 0·05 versus FLS treated with rTRAIL and sDR4. Data are the mean ± s.d. of four individual samples.

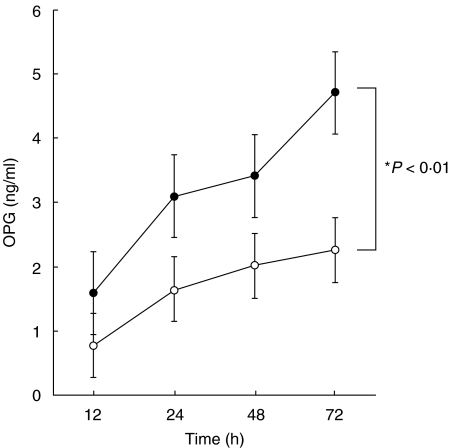

IL-1β-stimulated production of OPG by cultured FLS, which interferes with TRAIL-induced apoptogenic activity toward FLS

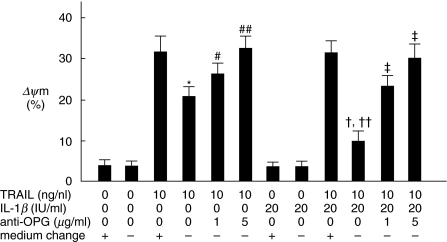

We examined the effects of inflammatory cytokines on OPG production by FLS. As shown in Fig. 4, OPG protein concentration increased time-dependently in the culture supernatants of FLS. Furthermore, such production was augmented by IL-1β at all time-points examined. Compared with IL-1β, the stimulatory effect of IL-6 (IL-6 + sIL-6 receptor) and TNF-α on OPG production from FLS was not found (data not shown). It was interesting to note that the rate of FLS apoptosis in response to TRAIL was decreased when rTRAIL was added without replacing the culture media (Fig. 5). Inhibition was more prominent in IL-1β-stimulated FLS compared with untreated FLS (Fig. 5), which was mainly restored by adding anti-OPG MoAb in culture media (Fig. 5). IL-1β treatment itself modulated neither TRAIL receptor expression (Fig. 6) nor TRAIL-mediated apoptosis (Fig. 5). These data suggest that OPG produced from FLS into the culture media is an endogenous receptor antagonist towards TRAIL-induced apoptosis of FLS.

Fig. 4.

IL-1β markedly stimulates OPG accumulation in culture supernatants of FLS. Rheumatoid FLS were cultured in the presence or absence of 20 IU/ml of IL-1β for indicated duration. After cultivation, OPG protein concentration in the culture supernatants was examined as described in the text. Open circles: unstimulated FLS, closed circles: IL-1β-treated FLS. *P < 0·01 versus unstimulated FLS. Data are mean ± s.d. of seven individual samples.

Fig. 5.

OPG produced from FLS inhibits TRAIL-mediated apoptosis in FLS. FLS were cultured in the presence or absence of 20 IU/ml of IL-1β for 72 h with or without adding anti-OPG MoAb (1 µg/ml or 5 µg/ml). After cultivation, 10 ng/ml of rTRAIL was added to the culture with or without exchanging the culture media for an additional 2 h. After incubation, apoptosis of FLS was quantified by ΔΨm as described in the text. Note that the sensitivity of FLS to TRAIL-mediated apoptosis was reduced when rTRAIL was added without exchanging the culture media, which was found significantly in IL-1β-treated FLS compared with unstimulated FLS. Furthermore, that inhibition was mainly restored by adding anti-OPG MoAb. Anti-OPG MoAb was mouse IgG1, thus 5 µg/ml of control mouse IgG1 (MBL) was used for negative control (0 µg/ml of anti-OPG MoAb means the addition of 5 µg/ml of control mouse IgG1). *P < 0·01 versus unstimulated FLS treated with rTRAIL with exchanging culture media. #P < 0·05. ##P < 0·01 versus unstimulated FLS treated with rTRAIL without exchanging culture media. †P < 0·01 versus IL-1β-stimulated FLS treated with rTRAIL with exchanging culture media. ††P < 0·05 versus unstimulated FLS treated with rTRAIL without exchanging culture media. ‡P < 0·01 versus IL-1β-stimulated FLS treated with rTRAIL without exchanging culture media. Data are the mean ± s.d. of four experiments.

Fig. 6.

IL-1β does not modulate the expression of DR4, DR5, DcR1 and DcR2 on FLS. Rheumatoid FLS, cultured in the presence or absence of rIL-1β (20 IU/ml) for 72 h, were detached by adding 0·265 mm EDTA and reacted with anti-DR4, anti-DR5, anti-DcR1 or anti-DcR2 at 4°C for 30 min. The cells were incubated further with PE-conjugated antigoat IgG at 4°C for 30 min, and surface expression of DR4, DR5, DcR1 and DcR2 on FLS was examined by flow cytometer as described in the text. Note that the expression of DR4, DR5, DcR1 and DcR2 on FLS was not changed by IL-1β treatment. NC: negative control, stained with goat IgG instead of first antibody. Numbers are the percentage of positive cells. Results are representative data from five individual samples.

DISCUSSION

Apoptosis occurs in a variety of physiological situations such as embryogenesis, and plays a crucial role in normal tissue homeostasis. However, a breakdown in the delicate balance between cell survival and apoptosis has been implicated in the pathogenesis of a number of rheumatic diseases, including RA [8]. The mechanisms responsible for synovial hyperplasia of RA patients may be explained by reduced synovial cell apoptosis, which cannot counteract the ongoing process of synovial cell proliferation.

TRAIL can interact potentially with five different receptors: two functional receptors DR4 and DR5, two decoy receptors DcR1 and DcR2, and a soluble decoy receptor OPG [12,17,18]. Other investigators have shown that DR5 is a sole death domain containing receptor for TRAIL on FLS [19]. We have shown here that DR5 was not sole but a prominent death domain-containing receptor for TRAIL. A previous study has shown that DR5 has the highest binding affinity towards TRAIL at 37°C [20]; however, detailed experiments such as RNA interference for each TRAIL receptor are necessary to clarify the difference.

Recent studies reported the production of OPG in culture supernatants from rheumatoid FLS [16]. Thus, we focused on the regulatory role of inflammatory cytokines on OPG production by rheumatoid FLS. Our data suggest that OPG production in the rheumatoid microenviroment is, at least in part, positively regulated by IL-1β, which is consistent with recent observations by Ziokowska et al. [16]. The positive correlation between IL-6 and OPG protein concentration found in the rheumatoid synovial fluid may result from the inducible effect of IL-1β on the production of IL-6 [21], as the effect of IL-6 on OPG production by synovial cells was not found compared with IL-1β. A promising inhibitory role of OPG on osteoclastogenesis in murine adjuvant arthritis has been identified, which is achieved through decoy function of OPG for RANKL; however, treatment of the mice with OPG failed to improve the severity of synovial inflammation [22]. The present study has demonstrated that OPG is a functional inhibitor of TRAIL-induced apoptosis in FLS. Therefore, we speculate that the functional role of OPG on synovial cell growth is separate from its inhibitory action on osteoclastogenesis; the former is mediated through decoy function towards TRAIL while the latter through decoy function towards RANKL. Expression of TRAIL receptors on FLS was not affected by IL-1β treatment, and the sensitivity of TRAIL-mediated apoptosis was not suppressed directly by IL-1β; however, TRAIL-mediated apoptogenic activity towards FLS was inhibited significantly in IL-1β-stimulated FLS culture. The production of OPG from cultured FLS was augmented by IL-1β, thus IL-1β may inhibit primarily TRAIL-induced apoptosis of FLS at death receptor level by OPG in a competitive manner. This is consistent with data from the blocking experiment, that neutralization of OPG produced from FLS by anti-OPG MoAb mainly restored TRAIL-mediated apoptogenic activity towards FLS. Although OPG protein concentration in culture supernatants from IL-1β-treated synovial cells was comparable to that inhibiting TRAIL-induced FLS apoptosis (compare Figs 3 and 4), the concentration was clearly higher than that in the synovial fluid of RA patients (compare Fig. 1 with Figs 3 and 4), which could not suppress TRAIL-induced apoptosis in FLS (see Figs 1 and 3). OPG protein concentration in rheumatoid synovial fluid reported by other groups [15,16,23] was much higher than the present data. Factors responsible for the difference are unclear; however, the variation in clinical situations of the subjects and MoAb used might result in the difference. Recent investigations have shown the elevation of OPG in rheumatoid synovial fluid, compared with serum consentration [15]; however, other investigators demonstrated a relatively low OPG protein concentration in the rheumatoid synovial fluid compared with synovial fluid from osteoarthritis patients [23]. Further investigation is necessary to clarify the functional expression of OPG in synovial tissue of RA patients.

TRAIL is thought to be an inhibitor of synovial cell hyperplasia as the blockage of TRAIL signalling by sDR5 in type II collagen-induced arthritis in mice exacerbates the proliferation of synovial cells [24]. Although we have not examined the expression of other soluble receptor antagonists such as sDR4 and sDR5 in the culture supernatants of FLS, our present study indicates that OPG produced by synovial cells acts as an endogenous decoy receptor of TRAIL-induced apoptosis, and part of the growth-promoting activity of IL-1β may be achieved by overproduction of OPG to suppress the biological function of TRAIL.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by grant-in-aid 13557042/13670461 from the Ministry of Education, Science, and Culture of Japan.

REFERENCES

- 1.Simonet WS, Lacey DL, Dunstan CR, et al. Osteoprotegerin: a novel secreted protein involved in the regulation of bone density. Cell. 1997;89:309–19. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80209-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tsuda E, Goto M, Mochizuki S, et al. Isolation of a novel cytokine from human fibroblasts that specifically inhibits osteoclastogenesis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;234:137–42. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yasuda H, Shima N, Nakagawa N, et al. Identity of osteoclastogenesis inhibitory factor (OCIF) and osteoprotegerin (OPG): a mechanism by which OPG/OCIF inhibits osteoclastogenesis in vitro. Endocrinology. 1998;139:1329–37. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.3.5837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tomoyasu A, Goto M, Fujise N, et al. Characterization of monomeric and homodimeric forms of osteoclastogenesis inhibitory factor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;245:382–7. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.8443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Collin-Osdoby P, Rothe L, Anderson F, Nelson M, Maloney W, Osdoby P. Receptor activator of NF-κB and osteoprotegerin expression by human microvascular endothelial cells, regulation by inflammatory cytokines, and role in human osteoclastogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:20659–72. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010153200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kwon BS, Wang S, Udagawa N, et al. TR1, a new member of the tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily, induces fibroblast proliferation and inhibits osteoclastogenesis and bone resorption. FASEB J. 1998;12:845–54. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.12.10.845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Malyankar UM, Scatena M, Suchland KL, et al. Osteoprotegerin is an αvβ3-induced, NF-êB-dependent survival factor for endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:20959–62. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C000290200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vaishnaw AK, McNally JD, Elkon KB. Apoptosis in the rheumatic diseases. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40:1917–27. doi: 10.1002/art.1780401102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kawakami A, Eguchi K, Matsuoka N, et al. Inhibition of Fas antigen-mediated apoptosis of rheumatoid synovial cells in vitro by transforming growth factor beta 1. Arthritis Rheum. 1996;39:1267–76. doi: 10.1002/art.1780390802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tsuboi M, Eguchi K, Kawakami A, et al. Fas antigen expression on synovial cells was down-regulated by interleukin 1 beta. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;218:280–5. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.0049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kawakami A, Nakashima T, Yamasaki S, et al. Regulation of synovial cell apoptosis by proteasome inhibitor. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42:2440–8. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199911)42:11<2440::AID-ANR23>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Emery JG, McDonnell P, Burke MB, et al. Osteoprotegerin is a receptor for the cytotoxic ligand TRAIL. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:14363–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.23.14363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miyashita T, Kawakami A, Tamai M, et al. Akt is an endogenous inhibitor toward tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis inducing ligand (TRAIL)-mediated apoptosis in rheumatoid synovial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;312:397–404. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.10.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arnett FC, Edworthy SM, Bloch DA, et al. The American Rheumatism Association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;31:315–24. doi: 10.1002/art.1780310302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feuerherm AJ, Borset M, Seidel C, et al. Elevated levels of osteoprotegerin (OPG) and hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) in rheumatoid arthritis. Scand J Rheumatol. 2001;30:229–34. doi: 10.1080/030097401316909585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ziolkowska M, Kurowska M, Radzikowska A, et al. High levels of osteoprotegerin and soluble receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa B ligand in serum of rheumatoid arthritis patients and their normalization after anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha treatment. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:1744–53. doi: 10.1002/art.10388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pan G, Ni J, Wei YF, Yu G, Gentz R, Dixit VM. An antagonist decoy receptor and a death domain-containing receptor for TRAIL. Science. 1997;277:815–8. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5327.815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pan G, O'Rourke K, Chinnaiyan AM, et al. The receptor for the cytotoxic ligand TRAIL. Science. 1997;276:111–3. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5309.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ichikawa K, Liu W, Fleck M, et al. TRAIL-R2 (DR5) mediates apoptosis of synovial fibroblasts in rheumatoid arthritis. J Immunol. 2003;171:1061–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.2.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Truneh A, Sharma S, Doyle ML, et al. Temperature-sensitive differential affinity of TRAIL for its receptors. DR5 is the highest affinity receptor. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:23319–25. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M910438199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Duff GW. Cytokines and acute phase proteins in rheumatoid arthritis. Scand J Rheumatol. 1994;100:9–19. doi: 10.3109/03009749409095197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kong YY, Feige U, Sarosi I, et al. Activated T cells regulate bone loss and joint destruction in adjuvant arthritis through osteoprotegerin ligand. Nature. 1999;402:304–9. doi: 10.1038/46303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kotake S, Udagawa N, Hakoda M, Tomatsu T, Suda T, Kamatani N. Activated human T cells directly induce osteoclastogenesis from human monocytes: possible role of T cells in bone destruction in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44:1003–12. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200105)44:5<1003::AID-ANR179>3.0.CO;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Song K, Chen Y, Goke R, et al. Tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) is an inhibitor of autoimmune inflammation and cell cycle progression. J Exp Med. 2000;191:1095–104. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.7.1095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]