Abstract

Murine experimental autoimmune thyroiditis (EAT), characterized by thyroid destruction after immunization with thyroglobulin (Tg), has long been a useful model of organ-specific autoimmune disease. More recently, porcine thyroid peroxidase (pTPO) has also been shown to induce thyroiditis, but these results have not been confirmed. When (C57BL/6 × CBA)F1 mice, recently shown to be susceptible to mouse TPO-induced EAT, were immunized with plasmid DNA to human TPO (hTPO) and cytokines IL-12 or GM-CSF, significant antibody (Ab) titres were generated, but minimal thyroiditis was detected in one mouse only from the TPO + GM-CSF immunized group. However, after TPO DNA immunization of HLA-DR3 transgenic class II-deficient NOD mice, thyroiditis was present in 23% of mice injected with TPO + IL-12 or GM-CSF. We also used another marker for assessing the closeness of the model to human thyroid autoimmunity by examining the epitope profile of the anti-TPO Abs to immunodominant determinants on TPO. Remarkably, the majority of the anti-TPO Abs was directed to immunodominant regions A and B, demonstrating the close replication of the model to human autoimmunity. TPO protein immunizations of HLA-DR3 transgenic mice with recombinant hTPO did not result in thyroiditis, nor did immunization of other mice expressing HLA class II transgenes HLA-DR4 or HLA-DQ8, with differential susceptibility to Tg-induced EAT. Moreover, our efforts to duplicate exactly the experimental procedures used with pTPO also failed to induce thyroiditis. The success of hTPO plasmid DNA immunization of DR3+ mice, similar to our reports on Tg-induced thyroiditis and thyrotropin receptor DNA-induced Graves’ hyperthyroidism, underscores the importance of DR3 genes for all three major thyroid antigens, and provides another humanized model to study autoimmune thyroid disease.

Keywords: thyroid peroxidase DNA, TPO DNA immunization, HLA-DR3, thyroid peroxidase

INTRODUCTION

The most common autoimmune disorder affecting humans is thyroid autoimmune disease [1]. Two entirely different diseases with a varying spectrum of endocrine function, namely destructive Hashimoto's thyroiditis (HT) leading to hypothyroidism, and Graves’ disease (GD) characterized by hyperthyroidism, are represented within these groups [2,3]. Both diseases are characterized by the production of autoantibodies (autoAbs) to thyroid specific antigens such as thyroglobulin (Tg) and thyroid peroxidase (TPO), although they differ in titres and frequency [2,3]. The majority of anti-TPO response (>90%) in all patients is directed to two discontinuous determinants on the surface of the molecule termed immunodominant region-A (IDR-A) and -B [4], following the nomenclature of the original description with mouse monoclonal Abs (mAbs) [5]. The anti-TPO autoAbs specific for IDR-A and -B determinants vary in different patients. The ratio is maintained for several years and is genetically transmitted in families [6,7]. Thus, the epitope profile of the anti-TPO response to IDRs can be used as a marker for human thyroid autoimmunity [4,6,7].

Thyroid autoimmune diseases are multifactorial disorders where, together with the genetic background and other constitutional factors, the environmental events contribute to disease development and progression. HLA-DRB1*0301 (DR3) has long been recognized to encode a strong susceptibility trait with these thyroid autoimmune disorders [8]. Supportive evidence has come from the recent incorporation of the DRA/DRB1*0301 transgene into major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II-knockout mice, either on the C57BL/10 (B10) or NOD background. The DR3 transgenic mice developed thyroid disorders resembling HT and GD after immunization with human Tg [9,10] and thyrotropin receptor (TSHR) [11,12].

While there is considerable overlap in terms of anti-Tg and anti-TPO Ab responses in HT and GD, it is interesting that induced experimental models of thyroid autoimmunity have long been described for Tg, but those for TPO and TSHR have lagged behind [13]. Experimental murine models of GD have only been described more recently by using several novel protocols for immunization with TSHR [14–16]. In the models, the coproduction of anti-TPO and anti-Tg Abs was not measured, but in the case of TSHR plasmid DNA immunization of DR3 transgenic mice, we detected stimulating Abs to TSHR, but only a low level of Abs to mouse Tg (mTg) in one animal with destructive thyroiditis [12]. The development of animal models with thyroiditis induced with TPO has been difficult, principally due to difficulties in purifying substantial quantities of TPO. Additionally, purification from thyroid glands needs careful standardization to ensure negligible contamination with Tg, which may distort the experimental model. An alternative source is recombinant human TPO (rhTPO) prepared in eukaryotic expression systems such as insect, yeast or mammalian cells. But the insect cell preparations are poorly glycosylated and not fully enzymatically active, with the consequence of significant contamination with denatured TPO [17–20]. Moreover, whilst the CHO cell-produced TPO is faithfully glycosylated [21], scale-up for production of substantial quantities can prove difficult. Despite these difficulties, early studies on immunization with TPO, prepared by trypsinization of porcine thyroid glands, and adjuvant, into different mouse strains showed that C57BL/6 (B6, H2b) strain was susceptible to lymphocytic infiltration [22], whilst BALB/c and other strains were resistant and some even failed to mount an Ab response [23]. Importantly, these studies also showed that the Abs were specific for the immunogen, porcine TPO (pTPO), in failing to cross-react with mouse TPO [22,23]. Furthermore, a thyroiditogenic 15-mer peptide from pTPO was identified, but the Abs induced with the pTPO peptide also failed to cross-react with mouse TPO [24].

Recently, the Ab response to TPO in mice has been studied in detail by applying some of the novel injection protocols developed for inducing TSHR Abs and hyperthyroid disease [25,26]. Importantly, immunization with hTPO plasmid or rhTPO adenovirus led to the generation of anti-TPO Abs that were predominantly restricted, like in human disease, to IDR-A and -B [26]. In this study, we have assessed the potential of TPO to induce thyroiditis in inbred as well as in several MHC class II transgenic animals [4,27]. We have used hTPO purified to a high degree of homogeneity from Graves’ thyroid glands [28], rhTPO, and plasmid hTPO with cytokine cDNA injections to thoroughly investigate the thyroiditogenic potential of TPO in experimental models. In addition, we have also re-examined the role of pTPO in inducing disease in B6 mice. Our results show that immunization with hTPO plasmid DNA replicated human autoimmunity, not only in terms of the anti-TPO response being dominated by specificity for IDR-A and -B, but also by the infiltration and thyroiditis in humanized DR3 transgenic mice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Antigens

A variety of TPO protein preparations were prepared from both human and porcine glands or as rhTPO. In addition, hTPO plasmid DNA was also used. TPO was purified from surgically excised, snap frozen pooled thyroid glands of Graves’ disease patients (hTPO) by Ab affinity chromatography, essentially as described [17,28]. To remove human IgG contamination, the affinity-purified hTPO was applied to a column containing 2 ml of Protein L-Sepharose (ACTIgen Cambridge, UK) and was eluted with PBS containing 0·05% DOC. Eluted fractions were concentrated on Amicon membrane PM 30 (AMICON- Beverly MA, USA) and stored at −70°C. The preparation was enzymatically active with a guaiacol-specific activity of 120–150 units/mg protein and >90% pure by Coomassie Blue staining of SDS polyacrylamide gel analysis. rhTPO was expressed in Sf9 insect cells using baculovirus and purified by Ab affinity chromatography and, after the Protein-L chromatography step, concentrated and stored in aliquots at −70°C [17]. This preparation was not enzymatically active with a purity of approximately 80%. The main impurities were represented by TPO degradation fragments of 80 and 45 kD [17]. Trypsinized pTPO was prepared according to the protocol of Rawitch et al. [29] with minor modifications. hTg was prepared from frozen human thyroids as described previously by fractionation of thyroid extracts in PBS on a SEPHADEX G-200 column (Pharmacia Inc., Piscataway, NJ, USA) [30]. pTg was purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA). Aliquots were stored at −20°C.

For genetic immunization of mice with TPO plasmid, the hTPO cDNA in pUV1 [31] was subcloned into the EcoR1 restriction site of pcDNA 3·1(+) vector (Invitrogen, Paisley, UK) and the orientation of the insert confirmed by BamH1 restriction. Plasmid DNA was prepared using QIAfilter Plasmid Giga kits (Qiagen) as described [32]. Mouse IL-12 and GM-CSF cDNAs cloned in pNGVL3 (University of Michigan Vector Core, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) and pEF-BOS [33], respectively, were used.

Conventional and transgenic mice

Female B6 (C57BL/6) and (C57BL/6 × CBA)F1 mice were purchased from Harlan Sprague-Dawley (via C. Reeder, NIH) and used at 8–14 weeks old. Transgenic mice deficient in endogenous class II molecules had either HLA or H2 class II transgene introduced. Five strains were used for immunization and their generations have been detailed elsewhere. Briefly, the HLA-DR3 (DRA/DRB1*0301) transgene [9] and the HLA-DQ8 (DQA1*0301/DQB1*0302) transgene [34] were introduced into class II-negative H2Ab0 (Aβ-chain-deficient) mice on the C57BL/10 (B10) background by mating. DR3+ Ab0 mice were also backcrossed to NOD (H2g7) mice to generate DR3+ Ab0/NOD mice [10]. The HLA-DR4β (DRB1*0401) transgene [35] was first introduced into H2Ab0 mice and then into the B10.RFB3 (H2f) strain by mating and backcross. B10.RFB3 has a nonfunctional Eb (β-chain) gene but a functional Ea (α-chain) gene; the conserved endogenous Eα chain pairs with the DR4β chain to express surface molecules with DR4 specificity. Congenic H2E+ B10.Ab0 transgenic mice were generated by introducing an Eak transgene into class II-deficient Ab0 mice, followed by repeated backcross to B10.Ab0 mice [36]. The conserved Eα chain pairs with the endogenous Eβ chain to express surface molecules with Eβb specificity.

All transgenic mice were bred and maintained in the pathogen-free Immunogenetics Mouse Core facility at the Mayo Clinic and transgene expression was verified by polymerase chain reaction followed by flow cytometry of peripheral blood leucocytes. Experimental mice were maintained in specific pathogen-free facility at Wayne State University and given acidified, chlorinated water at least 1 week prior to use at 10–16 weeks of age till the end of the experiment. Animal care was supervised by veterinarians in accordance with accredited institutional guidelines.

Induction of experimental autoimmune thyroiditis (EAT) by TPO protein or TPO plasmid DNA immunization

Two adjuvants were used to enhance the immunogenicity of TPO proteins. Salmonella enteritidis lipopolysaccharide (LPS) was prepared by TCA precipitation. Complete Freund's adjuvant (CFA) with Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Ra (supplemented to contain 3 mg/ml) was purchased from Difco Laboratories (Detroit, MI, USA). For TPO protein, B6 mice were immunized with 200 or 20 µg hTPO, rhTPO or 20 µg hTg in CFA emulsified at a 1 : 1 ratio. On days 0 and 7, 0·05 ml was injected subcutaneously into alternate thigh and hind footpad. Transgenic mice were either immunized with 100 µg antigen in CFA as above or with 100 µg rhTPO or 40 or 100 µg hTg intravenously (iv) on days 0 and 7, followed 3 h later by 20 µg LPS iv. On day 28 or 35, the sera, spleens or lymph nodes and thyroids were collected.

For plasmid DNA immunization, mice were treated in the muscles of both hind legs with 3·4 µg cardiotoxin (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA, USA) 5 days earlier. On week 0, 50 µg TPO plasmid with or without 50 µg IL-12 or GM-CSF plasmid in saline was injected into both hind legs of (C57BL/6 × CBA)F1 mice; in experiments with DR3+ Ab0/NOD mice, mice were not treated with TPO plasmid alone. Control mice were injected with 50 µg pcDNA 3·1 vector mixed with 50 µg GM-CSF plasmid. All injections were repeated on weeks 3 and 6. Animals were bled at weeks 8, 11 and at the time of sacrifice also for thyroid histology.

In vitroT cell proliferation assay

On day 28 or 35, depending on the route of immunization, spleen or lymph node cells were cultured for 4 or 5 days, at 6 × 105/well with 10–40 µg/ml antigens at 37°C and 5% CO2-air in flat-bottomed, 96-well plates [37,38]. Lymph node cells were cocultured with 1 × 106/well irradiated spleen cells from B6 mice. Culture medium RPMI 1640 was supplemented with 25 mm HEPES buffer, 2 mm glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 µg/ml streptomycin (all Gibco BRL, Grand Island, NY, USA), 50 µm 2-mercaptoethanol (Sigma) and 1% normal mouse serum (NMS). The cells were pulsed with 1 µCi of [3H]thymidine (ICN Pharmaceuticals, Costa Mesa, CA, USA) for the final 18 h and harvested onto glass fibre filters. [3H]-thymidine uptake was presented as cpm (mean ± SE) of triplicate cultures.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

Microtitre plates (Maxisorb 96 well; Nunc, Denmark) were coated with 100 µl of 1·0 µg/ml of the designated antigen in 0·1 m carbonate-bicarbonate buffer pH 9·6, overnight at 4°C. For rhTPO, the coated plates were left overnight in 0·1 m acetate-acetic acid buffer, pH 6·0, to remove the citraconyl residues and then washed with PBST (saline with 0·1% Tween-20) prior to use. After further washing and blocking with 0·5% BSA for 1 h at room temperature, 100 µl serum dilutions in PBST-0·2% BSA were added. After 1 h, the washed plates were incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (Dako, Denmark; 1 : 2000). After 1 h and washings, 100 µl of tetramethylbenzidine (0·1 mg/ml) in 0·1 m citric-phosphate buffer, pH 4·0, was added. After 15 min, 50 µl of 1 m sulphuric acid was added to stop the reaction and the optical density (OD) was measured at 450 nm. Mouse IgG subclasses of hTPO Abs were determined as described [39], using biotinylated rat mAbs to IgG1 and IgG2a and goat antisera to IgG2b and IgG3 (Caltag, Burlingame, CA, USA), followed by incubation with HRP-conjugated streptavidin (PharMingen, San Diego, CA, USA). NMS and blank wells without any serum were used as controls.

Determination of anti-TPO Abs to IDRs

We used two different reagents in competitive ELISA to determine IDR-A and -B specific Abs to TPO in the mouse sera [40–45]. Rabbit antipeptide sera, which have been well characterized for defining the IDR-A and -B specificities of anti-TPO Abs, were used [40–42]. In experiments with DR3 transgenic mice immunized with TPO DNA plasmid, we also used rhFabs in separate competition assays to confirm the specificities of anti-TPO Abs in the mouse sera. For Abs specific for IDR-B, to hTPO coated plates (1 µg/ml) were added rabbit antipeptide 14 (anti-P14) antiserum (1 : 100 dilution) and incubated overnight at room temperature [40]. For determination of IDR-A specificities, a mixture of rabbit anti-P12, P14, P18 and P43 antisera was used (all at 1 : 100 dilution) [41,42]. After washing, three different dilutions of immune mouse serum were added to the wells and incubated for 1 h at room temperature. After washing three times in TBST, HRP-conjugated rabbit anti-mouse IgG (Dako, Ely, UK) (diluted 1 : 2000) was added and incubated for 1 h followed by three washes with PBS. The plates were developed with TMB solution and the OD measured at 450 nm. Inhibition of autoAb binding was calculated according to the formula: where A is the OD of immune mouse sera in the presence of antipeptide antisera, B is the OD of NMS and T is the OD of immune mouse sera in the presence of preimmune rabbit serum [42]. All experiments were repeated at least 3 times. Any inhibition over 3SD for NMS was considered as significant.

Competitive inhibition ELISA with rhFabs was ascertained generally as described above [43]. rhFabs were added to hTPO-coated plates followed by three different dilutions of immune mouse serum. Inhibition was calculated as described above, except rhFabs and an irrelevant rhFab were used in the calculation of A and T, respectively.

Thyroid pathology

Thyroid sections were stained by haematoxylin & eosin. The percentage of thyroiditis was determined from 50 to 60 vertical sections (10–15 step levels) through both thyroid lobes. Thyroids with >10% thyroiditis showed definite follicular destruction in addition to focal areas of infiltration (>0–10%) [46,47].

RESULTS

TPO protein immunization in conventional and transgenic mice does not induce thyroiditis

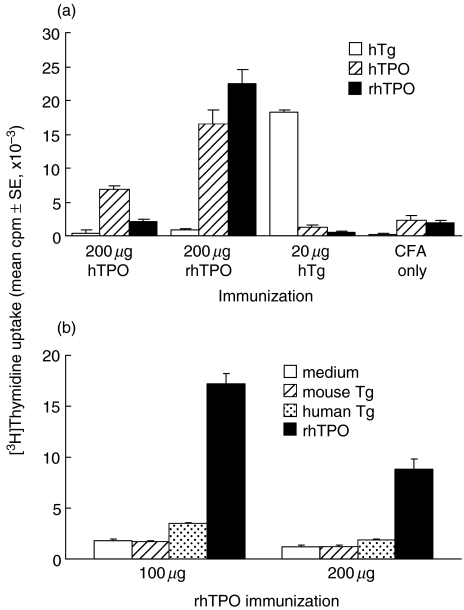

pTPO was previously reported by Kotani et al. [22] to induce thyroiditis in conventional B6 mice, a strain resistant to EAT induction with Tg [48]. Utilizing the same dosages in CFA as reported, we first attempted to induce EAT with 200 µg hTPO, purified from Graves’ thyroid tissue, or rhTPO. A low dose of 20 µg of each preparation was also used for immunization and hTg was included as a control. However, while a proliferative response of lymph node cells (Fig. 1a) and high Ab levels to hTPO were detected in all hTPO-immunized mice, none of the groups developed thyroiditis (data not shown). In the event that B6 mice responded to pTPO and not hTPO, we sought to confirm the thyroiditogenicity of pTPO, again using the protocol of Kotani et al. [22]. In addition to 200 µg, we included a low dose of 20 µg and 50 µg pTg for comparison. Although antipTPO and antipTg Abs were detected in high titres and the respective T cell proliferative response was observed, no thyroiditis resulted (data not shown). As mice of the b haplotype are resistant to both hTg- and mouse (m) Tg-induced EAT, the lack of thyroid infiltration after either hTg or pTg immunization was as expected. On the other hand, we could not confirm the report on pTPO induction of thyroiditis [22].

Fig. 1.

Proliferative response to TPO in B6 and DR3+ Ab0/NOD mice after TPO protein immunization. (a) B6 mice were immunized sc with 200 µg hTPO or rhTPO, or 20 µg hTg in CFA in the alternate thigh and hind footpad on days 0 and 7. Lymph node cells were obtained on day 35 and cultured (6 × 105/well) for 5 days with 20 µg/ml hTPO or rhTPO, or 40 µg/ml hTg, in the presence of 1 × 106/well irradiated spleen cells. [3H]-thymidine uptake is represented by cpm in culture with antigen. Background cpm without antigen ranged from 1500 ± 200–1900 ± 100. (b) DR3+ Ab0/NOD mice were immunized iv on days 0 and 7 with 100 or 200 µg rhTPO followed by 20 µg LPS. On day 28, spleen cells (6 × 105/well) were cultured for 4 days with medium alone, mTg or hTg (40 µg/ml) or rhTPO (10 µg/ml).

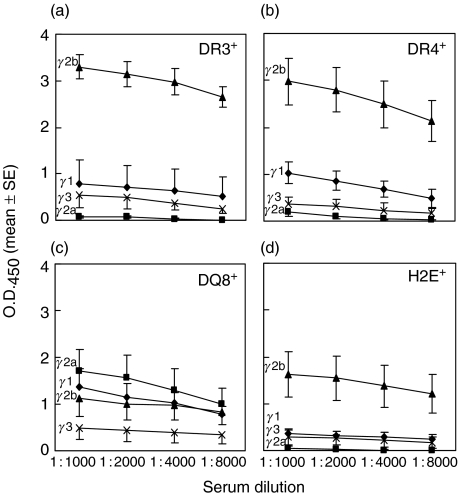

We next tested several HLA and one H2 class II-transgenic strains [9,36,49]. These strains, HLA-DR3, -DR4, -DQ8 and H2E, are on the B10 background, but still carry the H2b haplotype, similar to B6 mice. In addition, they express only the transgenes due to a class II gene knockout or inherent deficiency, and display a different susceptibility pattern to hTg-induced EAT. DR3+ mice are susceptible, DQ8+ mice are moderately susceptible but DR4+ mice are resistant [9,49]. The H2E+ strain is susceptible to hTg-, but not mTg-, induced EAT [36]. Using rhTPO to avoid possible complication from hTg contamination and CFA or LPS as adjuvants, we failed to induce thyroiditis in any strain, although anti-TPO Abs were readily detected (Table 1). The isotype levels varied from strain to strain, with the highest levels in DR3+ and DR4+ mice; all groups, except DQ8+ mice, showed a preponderance of IgG2b over IgG1 (Figs 2a–d).

Table 1.

Response of HLA and H2 class II transgenic mice to rhTPO and CFA or LPS immunization

| Antibody titre (mean ± SE) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| anti-rhTPO | |||||||

| Adjuvant | Transgene expression† | Antigen | anti-hTPO (1 : 200) | (1 : 100) | (1 : 1000) | anti-hTg (1 : 5000) | Thyroiditis incidence |

| CFA‡ | HLA-DR3 | rhTPO | 0·59 ± 0·23 | 0·25 ± 0·05 | – | – | 0/4 |

| CFA only | <0·2 | <0·1 | – | – | 0/3 | ||

| HLA-DQ8 | rhTPO | 2·54 ± 0·09 | – | – | – | 0/3 | |

| CFA only | <0·2 | – | – | – | 0/4 | ||

| H2E | rhTPO | 0·96 ± 0·34 | – | – | – | 0/3 | |

| CFA only | <0·2 | – | – | – | 0/2 | ||

| LPS§ | HLA-DR3 | rhTPO | – | – | 1·83 ± 0·27* | <0·2 | 0/8 |

| hTg | – | – | – | 1·76 ± 0·19 | 5/7 | ||

| HLA-DR4 | rhTPO | – | – | 2·46 ± 0·45* | <0·2 | 0/4 | |

| HLA-DQ8 | rhTPO | – | – | 0·32 ± 0·11 | <0·2 | 0/9 | |

| H2E | rhTPO | – | – | 2·22 ± 0·35 | <0·2 | 0/5 | |

| hTg | – | – | ≤ 0·2 | 2·19 ± 0·15 | 4/4 | ||

HLA-DR3, HLA-DQ8 or H2E transgene was introduced into class II-deficient mice on the B10 background; the HLA-DR4β chain transgene was introduced into B10.RFB3 mice deficient in the Eβ chain.

Mice were immunized sc with 100 µg of antigen in CFA into alternate thigh and hind footpad on days 0 and 7. The sera and thyroids were obtained on day 28.

Mice were immunized iv with 100 µg rhTPO or 100 µg (HLA-DR3) or 40 µg (H2E) hTg plus 20 µg LPS on days 0 and 7. The sera and thyroids were obtained on days 28 or 35.

Determined at 1 : 2000.

Fig. 2.

IgG isotype quantification of rhTPO antibodies. HLA or H2 transgenic mice, on the B10 background, were immunized iv with 100 µg rhTPO plus 20 µg LPS on days 0 and 7. Sera were obtained on days 28 or 35. Isotypes of IgG (⋄ IgG1; ▪ IgG2a, ▴ IgG2b; × IgG3) with specificity for rhTPO were quantified at various serum dilutions for (a) HLA-DR3+, (b) HLA-DR4+, (c) HLA-DQ8+ and (d) H2E+ mice.

Since thyroiditis was not induced by rhTPO in HLA class II transgenic Ab0/B10 mice, we next evaluated DR3 transgenic mice on the NOD background. These DR3+ Ab0/NOD mice develop more severe thyroiditis after immunization with mTg or hTg than DR3+ Ab0/B10 mice [50], possibly due to the autoimmune disease-prone nature of NOD mice [51]. Although a T cell proliferative response to rhTPO was detected in mice immunized with 100 or 200 µg rhTPO with LPS (Fig. 1b), no thyroiditis was seen (data not shown).

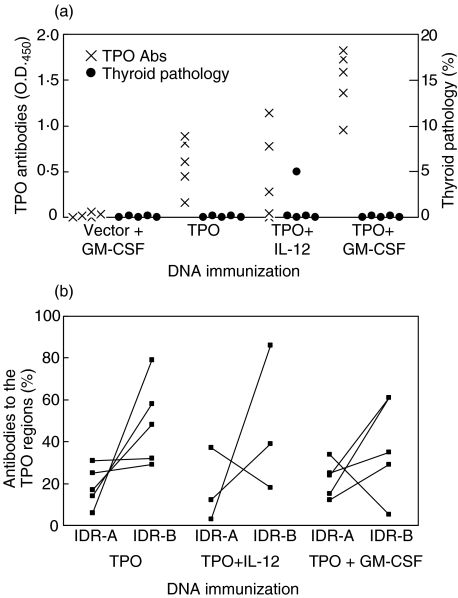

hTPO plasmid DNA immunization induces thyroid autoimmunity in (C57BL/6 × CBA)F1 mice

Thus far, the use of TPO protein had not induced EAT in the different transgenic strains tested. hTPO from thyroids is often contaminated with hTg and rhTPO produced in insect cells is not fully glycosylated [17,19,20]. We then turned to a protocol for genetic immunization with TSHR DNA [14]. (C57BL/6 × CBA)F1 mice were tested first, since they had recently been shown to be susceptible to murine recombinant TPO protein-induced EAT [52]. Mice were injected three times at weeks 0, 3 and 6 with hTPO DNA 5 days after cardiotoxin injection; two other groups were coimmunized with DNA for cytokines GM-CSF or IL-12. As seen in Fig. 3a, minimal mononuclear cell infiltration (<10% thyroiditis) was detected in only one mouse from the TPO + IL-12 immunized group 17 weeks after the first DNA injection. On the other hand, all mice developed anti-TPO Ab titres. Whereas the inclusion of IL-12 DNA had little effect on Ab levels, significantly higher titres were observed in mice coimmunized with GM-CSF DNA. As the mice were strongly positive for anti-TPO Abs, we also examined their repertoire to IDR-A and -B determinants by using our rabbit anti-TPO peptide antisera [40–42]. The results show that the anti-TPO response was indeed specific for both IDR determinants (Fig. 3b). Moreover, there was a similar percentage of anti-TPO Abs to IDR-A and -B determinants among the three TPO-immunized groups (Fig. 3b). In all four mice injected with TPO plasmid, the total IDR-A and -B specific TPO Ab response (> 80%) was dominant (Fig. 3b). Although inclusion of GM-CSF led to higher titres of anti-TPO Abs, the majority of the animals (3 out of 4) continued to show dominant responses (> 70%) to IDR-A and -B determinants (Fig. 3b). It was also interesting that, similar to patients with autoimmune thyroid disease [43], IDR-B specific Abs were present in greater amounts in mice immunized with TPO plasmid (3 of 5) or TPO + GM-CSF plasmids (3 of 4) (Fig. 3b).

Fig. 3.

hTPO antibodies and thyroiditis in (C57BL/6 × CBA)F1 mice after immunization with hTPO plasmid DNA with or without IL-12 or GM-CSF plasmid DNA. On weeks 0, 3 and 6, mice were injected with DNA, 5 days after cardiotoxin. Sera and thyroids were collected at the time of sacrifice (week 17). (a) IgG titres to rhTPO were determined from 1 : 4000 serum dilutions, except for control mice (1 : 1000 serum dilutions). Thyroid pathology was determined as in Methods. (b) Antibodies to immunodominant region (IDR) epitopes A and B of TPO. Since two mice from the TPO + IL-12 DNA immunized group showed no TPO Abs (A), no IDR-A versus -B determination could be made.

hTPO plasmid DNA immunization induces thyroid autoimmunity in DR3+ Ab0/NOD mice

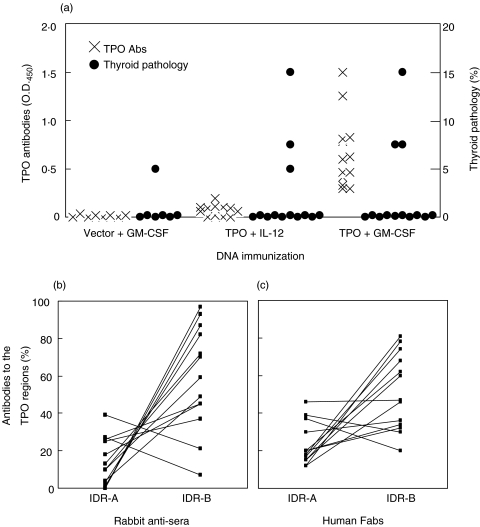

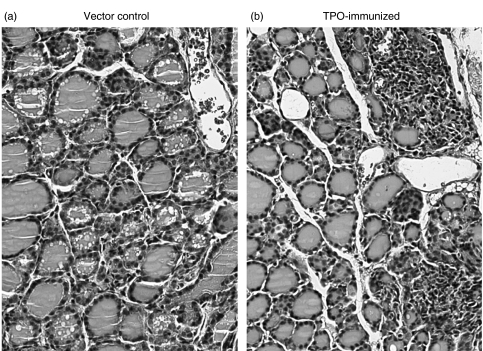

Given the HLA–DR3 association with HT and the susceptibility of DR3+ Ab0/NOD mice to hTg-induced EAT [50] and TSHR DNA-induced GD-like hyperthyroidism [12], we also immunized DR3+ Ab0/NOD mice with hTPO DNA. Similar to the protocol for F1 mice, three DNA injections at weeks 0, 3 and 6 were performed 5 days after the cardiotoxin injection; IL-12 or GM-CSF DNA was coimmunized with TPO DNA. When mice were examined at week 14, only co-immunization with GM-CSF resulted in detectable TPO Ab titres (Fig. 4a). On the other hand, thyroiditis was observed in 3 of 13 (23%) mice coimmunized with either IL-12 or GM-CSF DNA; thyroid destruction (∼15% thyroiditis) was seen in one of the three in both groups (Fig. 4a). An example of the multifocal mononuclear cell infiltration is shown in Fig. 5. Low levels of Abs to mTg were also detected in some sera (1 : 50), but they did not correlate with thyroid pathology or TPO Ab titres (data not shown), similar to the lack of correlation we observed after TSHR DNA immunization [12].

Fig. 4.

hTPO antibodies and thyroiditis in DR3+ Ab0/NOD mice after immunization with hTPO plasmid DNA with IL-12 or GM-CSF plasmid DNA. On weeks 0, 3 and 6, mice were injected with DNA, 5 days after cardiotoxin. Sera and thyroids were collected at the time of sacrifice (week 14). (a) IgG titres to rhTPO were determined from 1 : 4000 serum dilutions, except for control and TPO + IL-12 immunized groups (1 : 100 serum dilutions). Thyroid pathology was determined as in Methods. Antibodies to immunodominant region (IDR) epitopes A and B of TPO, from TPO + GM-CSF DNA immunized mice, as determined by rabbit antisera (b) or hFabs (c).

Fig. 5.

Mononuclear cell infiltration in the thyroid of hTPO plasmid DNA-immunized mice. Thyroid sections from (a) a vector control DR3+Ab0/NOD mouse and (b) a DR3+Ab0/NOD mouse immunized with TPO + GM-CSF plasmid DNA with infiltration involving >10–20% of the gland. (Magnification 200×).

Epitope profiles of the TPO Abs induced only in the TPO + GM-CSF group showed that in all 13 mice, there was almost 100% dominance of the Ab specificities directed towards the IDR-A and -B determinants on TPO (Fig. 4b), as determined by rabbit anti-peptide antisera with overlapping specificities for autoAbs in patients with thyroid autoimmune disease [40–42]. For confirmation, we also used rhFabs prepared from patients with thyroid autoimmunity in competition studies [43]; nearly 100% dominance of the anti-TPO Ab response to the IDR specificities was again observed (Fig. 4c). Furthermore, the recognition of the IDR-B epitope was greater than that of the IDR-A determinant in almost all sera (Figs 4b,c). Thus the anti-TPO Ab response induced in humanized DR3+ Ab0/NOD transgenic mice shows restrictions in their epitope profile that mimics those present in patients with thyroid autoimmune disease, with preference towards the IDR-B determinant of TPO [43].

DISCUSSION

Purified preparations of TPO have previously been used to immunize inbred strains of mice to generate mAbs [5,53], to study the Ab epitope responses to TPO [25,26] or to establish an experimental animal model for thyroiditis [23,24]. In this report, our initial attempts focused on using highly purified hTPO with undetectable Tg contamination in B6 (H2b) mice, a strain previously shown to be susceptible to thyroiditis induced with pTPO [22]. As already shown by others [25], Abs were readily induced in all mice. A strong T cell response was also apparent (Fig. 1a), but it was not accompanied by thyroid infiltration. The T cell response was probably directed predominantly to heterologous T cell determinants on hTPO that did not cross-react with the mTPO, as has been shown with hTg [48]. More importantly, our attempts to reproduce the earlier studies using pTPO [22] in B6 mice also failed to result in thyroiditis. We cannot be certain of the reasons for this discrepancy, but one possibility may be that our trypsinized pTPO preparation was depleted of contaminating Tg by Ab-affinity chromatography to yield a preparation with no detectable Tg by highly sensitive ELISA. The preparations reported by Kotani et al. [22] did not include a measure of Tg contamination, although we find that 50 µg of pTg in adjuvant was also not permissive for inducing thyroid inflammation in B6 mice.

We then tested several MHC class II transgenic animals, all with H2b background, which have shown discrimination in susceptibility to hTg and mTg [36,49]. Using rhTPO (to exclude minute quantities of Tg contamination), high titre Abs were induced with different adjuvants, but none of the different MHC transgenic mice showed any evidence of thyroiditis (Table 1). Since we had recently shown that DR3+ Ab0/NOD mice develop more severe thyroiditis after immunization with hTg than DR3+ Ab0 mice [50], we immunized DR3+ Ab0/NOD mice with rhTPO, but no thyroiditis developed. The strong T cell response obtained in vitro did indicate that DR3-binding peptides were processed and presented (Fig. 1). The spectrum of naturally processed TPO peptides binding DR3 has not been investigated further, as no thyroiditis was obtained.

It is now clear that, for a number of organ-specific diseases such as thyroid autoimmunity [25,54,55], type 1 diabetes [56] and primary biliary cirrhosis [57], immunization with the target protein in adjuvant does not faithfully reproduce the autoimmune disorder. However, these above models have relied on using heterologous antigens for immunizing mice, which leads to the preferential priming of T cells to the foreign determinants with little or no cross-reactivity to the mouse antigen [48]. This is already illustrated in a recent homologous model study, where challenge with recombinant mouse TPO in adjuvant in (C57BL/6 × CBA)F1 mice led to the successful induction of thyroiditis [52]. However, the same F1 mice immunized with hTPO plasmids showed minimal thyroid infiltration only in one mouse. In contrast, we induced thyroiditis in approximately 25% of DR3+ Ab0/NOD transgenic mice immunized with hTPO plasmids, whereas <10% of unimmunized mice developed thyroiditis (unpublished observations). Thus, the DR3 allele is permissive and appears critical to the development of thyroid infiltration with TPO, in addition to Tg [9] and TSHR [11,12]. Importantly, the DR3 haplotype (HLA-DRB1*0301), as implicated in thyroid autoimmunity [8], is a strong susceptibility haplotype for all three major thyroid autoantigens.

Abs to TPO were readily induced by immunization with TPO + GM-CSF plasmids only, compared to groups given no cytokine or IL-12 DNA. Although we have not measured the isotypes or affinities of the TPO Abs, their epitope profiles mirror those present in thyroid disease patients. It is noteworthy that immunization of DR3+ Ab0/NOD transgenic mice led to almost 100% of the anti-TPO response dominated by the IDR-A and -B specificities as in human patients (Fig. 4b,c). In contrast, purified TPO protein leads to the generation of a lower proportion of the Abs to the IDR-A and -B determinants in mice [25] or in rabbits [28], where a small proportion (40%) is directed to the dominant regions of TPO (unpublished observation). Thus, as shown recently [26], and confirmed in this study, plasmid DNA immunization of TPO readily induces Abs that are restricted predominantly to the immunodominant epitopes. We cannot readily explain the effectiveness of plasmid immunizations in mimicking the response that arises in human patients, but the dose of immunization [26], together with the fact that the immunogen is synthesized in vivo, may play an important role. Another unexpected finding was the dominance of the induced Abs in DR3+ Ab0/NOD mice to the IDR-B epitope of TPO. It is possible that this relates to the DR3 haplotype skewing the Ab response to a particular dominant determinant. However, whether DR3+ individuals with thyroid autoimmune disease, positive for anti-TPO Abs, show a preferential response to the IDR-B epitope is not known, but would be of particular interest and easily studied.

In summary, we have investigated in-depth the potential of TPO to develop an experimental model of destructive thyroiditis. Immunizations of purified TPO preparations, including rhTPO to exclude Tg contamination, failed to show any evidence of thyroid inflammation in inbred or humanized transgenic mice. Plasmid immunizations appear to be the method of choice for inducing inflammatory disease in DR3+ Ab0/NOD mice. While the incidence remains low, it could potentially be improved by immunizing with pathogenic T cell epitopes shared between hTPO and mTPO, since, similar to Tg, hTPO and mTPO have 73% homology [58]. Moreover, the induced TPO Abs in the DR3+ Ab0/NOD animals resemble those present in patients serum in their epitopic profile and restriction to the immunodominant determinants on TPO. The development of this new model, together with the recently described homologous mTPO model [52] will allow studies on the genetic factors predisposing to this restricted Ab profile and its role in thyroid destruction.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by NIDDK grant DK45960 and a grant from St. John Hospital & Medical Center (Y.M.K), a grant from The Wellcome Trust (J.P.B and A.G) and The Medical Centre of Postgraduate Education grant CMKP 501-06-99 (A.G). We are grateful to Professor Anthony P. Weetman and Dr Philip Watson (University of Sheffield, Sheffield, UK) for providing anti-human TPO human Fabs. We thank Julie Hanson and staff for the breeding and care of mice and Ann Mazurco for histological preparation of thyroids.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jacobson DL, Gange SJ, Rose NR, Graham NMH. Epidemiology and estimated population burden of selected autoimmune diseases in the United States. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1997;84:223–43. doi: 10.1006/clin.1997.4412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weetman AP, McGregor AM. Autoimmune thyroid disease: further developments in our understanding. Endocr Rev. 1994;15:788–830. doi: 10.1210/edrv-15-6-788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rapoport B, McLachlan SM. Thyroid autoimmunity. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:1253–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI14321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Banga JP. Developments in our understanding of the structure of thyroid peroxidase and the relevance of these findings to autoimmunity. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes. 1998;5:275–81. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ruf J, Toubert M-E, Czarnocka B, Durand-Gorde J-M, Ferrand M, Carayon P. Relationship between immunological structure and biochemical properties of human thyroid peroxidase. Endocrinology. 1989;125:1211–8. doi: 10.1210/endo-125-3-1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jaume JC, Burek CL, Hoffman WH, Rose NR, McLachlan SM, Rapoport B. Thyroid peroxidase autoantibody epitopic ‘fingerprints’ in juvenile Hashimoto's thyroiditis: evidence for conservation over time and in families. Clin Exp Immunol. 1996;104:115–23. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1996.d01-659.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McLachlan SM, Rapoport B. Genetic and epitopic analysis of thyroid peroxidase (TPO) autoantibodies: markers of the human thyroid autoimmune response. Clin Exp Immunol. 1995;101:200–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1995.tb08339.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vaidya B, Kendall-Taylor P, Pearce SHS. Genetics of endocrine disease: the genetics of autoimmune thyroid disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:5385–97. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-020492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kong YM, Lomo LC, Motte RW, Giraldo AA, Baisch J, Strauss G, Hämmerling GJ, David CS. HLA-DRB1 polymorphism determines susceptibility to autoimmune thyroiditis in transgenic mice: definitive association with HLA-DRB1*0301 (DR3) gene. J Exp Med. 1996;184:1167–72. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.3.1167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Flynn JC, Fuller BE, Giraldo AA, Panos JC, David CS, Kong YM. Flexibility of TCR repertoire and permissiveness of HLA-DR3 molecules in experimental autoimmune thyroiditis in nonobese diabetic mice. J Autoimmun. 2001;17:7–15. doi: 10.1006/jaut.2001.0528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pichurin P, Chen C-R, Pichurina O, David C, Rapoport B, McLachlan SM. Thyrotropin receptor-DNA vaccination of transgenic mice expressing HLA-DR3 or HLA-DQ6b. Thyroid. 2003;13:911–7. doi: 10.1089/105072503322511300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Flynn JC, Rao PV, Gora M, et al. Graves’ hyperthyroidism and thyroiditis in HLA-DRB1*0301 (DR3) transgenic mice after immunization with thyrotropin receptor DNA. Clin Exp Immunol. 2004;135:35–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2004.02333.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kong YM. Experimental models for autoimmune thyroid disease: recent developments. In: Volpe R, editor. Contemporary Endocrinology: Autoimmune Endocrinopathies. Totowa NJ: Humana Press Inc; 1999. pp. 91–3. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Costagliola S, Many M-C, Denef J-F, Pohlenz J, Refetoff S, Vassart G. Genetic immunization of outbred mice with thyrotropin receptor cDNA provides a model of Graves’ disease. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:803–11. doi: 10.1172/JCI7665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shimojo N, Kohno Y, Yamaguchi K, et al. Induction of Graves-like disease in mice by immunization with fibroblasts transfected with the thyrotropin receptor and a class II molecule. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:11074–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.20.11074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nagayama Y, Kita-Furuyama M, Ando T, Nakao K, Mizuguchi H, Hayakawa T, Eguchi K, Niwa M. A novel murine model of Graves’ hyperthyroidism with intramuscular injection of adenovirus expressing the thyrotropin receptor. J Immunol. 2002;168:2789–94. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.6.2789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gardas A, Sutton BJ, Piotrowska U, Pasieka Z, Barnett PS, Huang GC, McGregor AM, Banga JP. Distinct immunological and biochemical properties of thyroid peroxidase purified from human thyroid glands and recombinant protein produced in insect cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1433:229–39. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4838(99)00128-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wedlock N, Furmaniak J, Fowler S, et al. Expression of human thyroid peroxidase in the yeasts Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Hansenula polymorpha. J Mol Endocrinol. 1993;10:325–36. doi: 10.1677/jme.0.0100325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grennan Jones F, Wolstenholme A, Fowler S, Smith S, Ziemnicka K, Bradbury J, Furmaniak J, Rees Smith B. High-level expression of recombinant immunoreactive thyroid peroxidase in the High Five insect cell line. J Mol Endocrinol. 1996;17:165–74. doi: 10.1677/jme.0.0170165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fan J-L, Patibandla SA, Kimura S, Rao TN, Desai RK, Seetharamaiah GS, Kurosky A, Prabhakar BS. Purification and characterization of a recombinant human thyroid peroxidase expressed in insect cells. J Autoimmun. 1996;9:529–36. doi: 10.1006/jaut.1996.0071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guo J, McLachlan SM, Hutchison S, Rapoport B. The greater glycan content of recombinant human thyroid peroxidase of mammalian than of insect cell origin facilitates purification to homogeneity of enzymatically protein remaining soluble at high concentration. Endocrinology. 1998;139:999–1005. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.3.5782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kotani T, Umeki K, Hirai K, Ohtaki S. Experimental murine thyroiditis induced by porcine thyroid peroxidase and its transfer by the antigen-specific T cell line. Clin Exp Immunol. 1990;80:11–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1990.tb06434.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McLachlan SM, Atherton MC, Nakajima Y, Napier J, Jordan RK, Clark F, Smith BR. Thyroid peroxidase and the induction of autoimmune thyroid disease. Clin Exp Immunol. 1990;79:182–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1990.tb05176.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kotani T, Umeki K, Yagihashi S, Hirai K, Ohtaki S. Identification of thyroiditogenic epitope on porcine thyroid peroxidase for C57BL/6 mice. J Immunol. 1992;148:2084–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jaume JC, Guo J, Wang Y, Rapoport B, McLachlan SM. Cellular thyroid peroxidase (TPO), unlike purified TPO and adjuvant, induces antibodies in mice that resemble autoantibodies in human autoimmune thyroid disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84:1651–7. doi: 10.1210/jcem.84.5.5666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guo J, Pichurin P, Nagayama Y, Rapoport B, McLachlan SM. Insight into antibody responses induced by plasmid or adenoviral vectors encoding thyroid peroxidase, a major thyroid autoantigen. Clin Exp Immunol. 2003;132:408–15. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2003.02170.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kong YM, David CS. New revelations in susceptibility to autoimmune thyroiditis by the use of H2 and HLA class II transgenic models. Int Rev Immunol. 2000;19:573–85. doi: 10.3109/08830180009088513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gardas A, Sohi MK, Sutton BJ, McGregor AM, Banga JP. Purification and crystallisation of the autoantigen thyroid peroxidase from human Graves’ thyroid tissue. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;237:366–70. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rawitch AB, Taurog A, Chernoff SB, Dorris ML. Hog thyroid peroxidase: physical, chemical, and catalytic properties of the highly purified enzyme. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1979;194:244–57. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(79)90615-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kong YM, David CS, Giraldo AAEI, Rehewy M, Rose NR. Regulation of autoimmune response to mouse thyroglobulin. influence of H-2D-end genes. J Immunol. 1979;123:15–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kimura S, Kotani T, McBride OW, Umeki K, Hirai K, Nakayama T, Ohtaki S. Human thyroid peroxidase: complete cDNA and protein sequence, chromosome mapping, and identification of two alternately spliced mRNAs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:5555–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.16.5555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rao PV, Watson PF, Weetman AP, Carayanniotis G, Banga JP. Contrasting activities of thyrotropin receptor antibodies in experimental models of Graves’ disease induced by injection of transfected fibroblasts or deoxyribonucleic acid vaccination. Endocrinology. 2003;144:260–6. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-220688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pilon SA, Piechocki MP, Wei W-Z. Vaccination with cytoplasmic ErbB-2 DNA protects mice from mammary tumor growth without anti-ErbB-2 antibody. J Immunol. 2001;167:3201–6. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.6.3201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nabozny GH, Baisch JM, Cheng S, Cosgrove D, Griffiths MM, Luthra HS, David CS. HLA-DQ8 transgenic mice are highly susceptible to collagen-induced arthritis: a novel model for human polyarthritis. J Exp Med. 1996;183:27–37. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pan S, Trejo T, Hansen J, Smart M, David CS. HLA-DR4 (DRB1*0401) transgenic mice expressing an altered CD4-binding site. specificity and magnitude of DR4-restricted T cell response. J Immunol. 1998;161:2925–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wan Q, Shah R, McCormick DJ, Lomo LC, Giraldo AA, David CS, Kong YM. H2-E transgenic class II-negative mice can distinguish self from nonself in susceptibility to heterologous thyroglobulins in autoimmune thyroiditis. Immunogenetics. 1999;50:22–30. doi: 10.1007/s002510050682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Simon LL, Justen JM, Giraldo AA, Krco CJ, Kong YM. Activation of cytotoxic T cells and effector cells in experimental autoimmune thyroiditis by shared determinants of mouse and human thyroglobulins. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1986;39:345–56. doi: 10.1016/0090-1229(86)90098-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Flynn JC, Conaway DH, Cobbold S, Waldmann H, Kong YM. Depletion of L3T4+ and Lyt-2+ cells by rat monoclonal antibodies alters the development of adoptively transferred experimental autoimmune thyroiditis. Cell Immunol. 1989;122:377–90. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(89)90085-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yan X-M, Guo J, Pichurin P, Tanaka K, Jaume JC, Rapoport B, McLachlan SM. Cytokines, IgG subclasses and costimulation in a mouse model of thyroid autoimmunity induced by injection of fibroblasts co-expressing MHC class II and thyroid autoantigens. Clin Exp Immunol. 2000;122:170–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2000.01362.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hobby P, Gardas A, Radomski R, McGregor AM, Banga JP, Sutton BJ. Identification of an immunodominant region recognized by human autoantibodies in a three-dimensional model of thyroid peroxidase. Endocrinology. 2000;141:2018–26. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.6.7506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gora M, Gardas A, Wiktorowicz W, Hobby P, Watson PF, Weetman AP, Sutton BJ, Banga JP. Evaluation of conformational epitopes on thyroid peroxidase by antipeptide antibody binding and mutagenesis. Clin Exp Immunol. 2004;136:137–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2004.02422.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jastrzebska-Bohaterewicz E, Gardas A. Proportion of antibodies to the A and B immunodeterminant regions of thyroid peroxidase in Graves’ and Hashimoto's disease. Autoimmunity. 2004 doi: 10.1080/0891693042000193339. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McIntosh RS, Asghar MS, Kemp EH, Watson PF, Gardas A, Banga JP, Weetman AP. Analysis of immunoglobulin Gκ antithyroid peroxidase antibodies from different tissues in Hashimoto's thyroiditis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82:3818–25. doi: 10.1210/jcem.82.11.4348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Czarnocka B, Janota-Bzowski M, McIntosh RS, Asghar MS, Watson PF, Kemp EH, Carayon P, Weetman AP. Immunoglobulin Gκ antithyroid peroxidase antibodies in Hashimoto's thyroiditis: epitope-mapping analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82:2639–44. doi: 10.1210/jcem.82.8.4124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Guo J, McIntosh RS, Czarnocka B, Weetman AP, Rapoport B, McLachlan SM. Relationship between autoantibody epitopic recognition and immunoglobulin gene usage. Clin Exp Immunol. 1998;111:408–14. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1998.00492.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rose NR, Twarog FJ, Crowle AJ. Murine thyroiditis. importance of adjuvant and mouse strain for the induction of thyroid lesions. J Immunol. 1971;106:698–704. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kong YM. Experimental autoimmune thyroiditis in the mouse. In: Coligan JE, Kruisbeek AM, Margulies DH, Shevach EM, Strober W, editors. Current Protocols in Immunology. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 1996. pp. 15.7.1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kong YM. The mouse model of autoimmune thyroid disease. In: McGregor AM, editor. Immunology of Endocrine Diseases. Lancaster: MTP Press Limited; 1986. pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wan Q, Shah R, Panos JC, Giraldo AA, David CS, Kong YM. HLA-DR and HLA-DQ polymorphism in human thyroglobulin-induced autoimmune thyroiditis: DR3 and DQ8 transgenic mice are susceptible. Human Immunol. 2002;63:301–10. doi: 10.1016/s0198-8859(02)00360-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Flynn JC, Wan Q, Panos JC, McCormick DJ, Giraldo AA, David CS, Kong YM. Coexpression of susceptible and resistant HLA class II transgenes in murine experimental autoimmune thyroiditis: DQ8 molecules downregulate DR3-mediated thyroiditis. J Autoimmun. 2002;18:213–20. doi: 10.1006/jaut.2002.0587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Leiter EH. The NOD Mouse Meets the ‘Nerup Hypothesis’: Is Diabetogenesis the Result of a Collection of Common Alleles Present in Unfavorable Combinations? In: Shafrir E, editor. Frontiers in diabetes researchLessons from animal diabetes III. London: Smith-Gordon; 1990. pp. 54–8. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ng HP, Banga JP, Kung AWC. Development of a murine model of autoimmune thyroiditis induced with homologous mouse thyroid peroxidase. Endocrinology. 2004;145:809–16. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-0656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ewins DL, Barnett PS, Tomlinson RWS, McGregor AM, Banga JP. Mapping epitope specificities of monoclonal antibodies to thyroid peroxidase using recombinant antigen preparations. Autoimmunity. 1992;11:141–9. doi: 10.3109/08916939209035148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Carayanniotis G, Huang GC, Nicholson LB, Scott T, Allain P, McGregor AM, Banga JP. Unaltered thyroid function in mice responding to a highly immunogenic thyrotropin receptor. implications for the establishment of a mouse model for Graves’ disease. Clin Exp Immunol. 1995;99:294–302. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1995.tb05548.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Banga JP. Immunopathogenicity of thyrotropin receptor – ability to induce autoimmune thyroid disease in an experimental animal model. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 1996;104(Suppl. 3):32–4. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1211678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nepom G, Quinn A, Sercarz E, Wilson DB. How important is GAD in the etiology of spontaneous disease in human and murine type 1 diabetes? J Autoimmun. 2003;20:193–4. doi: 10.1016/s0896-8411(03)00027-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rowley MJ, Maeda T, Mackay IR, Loveland BE, McMullen GL, Tribbick G, Bernard CCA. Differing epitope selection of experimentally-induced and natural antibodies to a disease-specific autoantigen, the E2 subunit of pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (PDC-E2) Inter Immunol. 1992;4:1245–53. doi: 10.1093/intimm/4.11.1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kotani T, Umeki K, Yamamoto I, Takeuchi M, Takechi S, Nakayama T, Ohtaki S. Nucleotide sequence of the cDNA encoding mouse thyroid peroxidase. Gene. 1993;123:289–90. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90141-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]