Abstract

Protection against tuberculosis depends upon the generation of CD4+ T cell effectors capable of producing IFN-γ and stimulating macrophage antimycobacterial function. Effector CD4+ T cells are known to express CD44hiCD62Llo surface phenotype. In this paper we demonstrate that a population of CD44hiCD62Llo CD4+ effectors generated in response to Mycobacterium bovis BCG or M. tuberculosis infection in C57BL/6 mice is heterogeneous and consists of CD27hi and CD27lo T cell subsets. These subsets exhibit a similar degree of in vivo proliferation, but differ by the capacity for IFN-γ production. Ex vivo isolated CD27lo T cells express higher amounts of IFN-γ RNA and contain higher frequencies of IFN-γ producers compared to CD27hi subset, as shown by real-time PCR, intracellular staining for IFN-γ and ELISPOT assays. In addition, CD27lo CD4+ T cells uniformly express CD44hiCD62Llo phenotype. We propose that CD27lo CD44hiCD62Llo CD4+ T cells represent highly differentiated effector cells with a high capacity for IFN-γ secretion and antimycobacterial protection at the site of infection.

Keywords: lung, T lymphocytes, cell surface molecules, tuberculosis, vaccination

INTRODUCTION

Despite widespread use of Bacille Calmette-Guerin (BCG) vaccination, tuberculosis (TB) continues to be a major cause of human mortality. BCG efficacy is about 50% with a range from 0% to 80% [1]. Development of new vaccines and improvement of the currently used BCG vaccine require that we better understand the mechanisms by which antigen-specific protection is induced in the lung and identify surrogate indicators that would aid in predicting new vaccine efficacy.

Protection against Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection is critically dependent on T cell responses [2,3]. Although CD8+ and γδ T cells contribute to protection [4,5], CD4+ T cells capable of producing IFN-γ and activating macrophage antimycobacterial functions are thought to be the major protective subset [6–10]. A convincing evidence for the role of IFN-γ in TB resistance comes from studies in human families bearing missense mutations in IFN-γ or IFN-γR encoding genes and from experiments in ifng and ifngr gene knock-out mice [8,9,11,12]. Not only a complete lack of function but quantitative differences in the level of IFN-γ production influence the progress of TB infection [13]. Finally, accelerated/increased IFN-γ response is thought to be the major mechanism of BCG-induced protection against TB [14,15].

Several recent studies demonstrated that immunological memory is predetermined by the type of effector response to the first encounter of the host with pathogen [16]. Thus, differentiation of naïve CD4 T cells into IFN-γ producing effectors is a critical event for protection against TB. Generation of IFN-γ response is normally accompanied by cell expansion and modifications in the expression of surface molecules participating in T cell extravasation and trafficking. However, the exact relationships between cell phenotype, proliferative activity and capacity to produce effector cytokines are not completely understood.

In murine models of M. tuberculosis and M. bovis infection, accumulation of CD4 T cells with decreased CD62L and increased CD44 expression at the site of infection has been shown [17–21]. IFN-γ producing cells have also been reported to bear a CD44hi, CD62Llo phenotype [20–22]. On the other hand, uncommitted IL-2+, IFN-γ-negative CD4 cells, generated in vivo during Th-1 biased antigen-driven responses also express CD44hi phenotype [23]. From other experimental models, it has recently become clear that capacity to produce IFN-γ depends upon several rounds of cell division [24,25]. However IFN-γ production in the absence of cell cycle progression has also been reported [26,27]. Finally, T cells have been shown to up-regulate CD44 and down-regulate CD62L after successful antigen-driven cell cycling [25]. But, not all CD44hi and CD62Llo T cells proliferate [26,28] and memory CD4+ T cells proliferating in response to stimulation with recall antigen can express CD62Lhi phenotype [29]. In summary, T cells with CD44hiCD62Llo phenotype, usually referred to as effector/memory cells, can be heterogeneous with respect to their capacity to proliferate and produce effector cytokines. Given that CD44hiCD62Llo cells display a heterogeneous surface phenotype [30,31], it is possible that expression of other molecules could better mark a population of differentiated IFN-γ producing T cells.

In this study, we have analysed expression of different surface molecules by lung CD4+ cells during primary response to M. bovis BCG and M. tuberculosis. We have found that in addition to previously reported changes in CD44 and CD62L surface expression on CD4 T cells, mycobacteria infection induces down-regulation of CD27 expression by a subset of CD4 T cells in the lung. We report that CD44hiCD62Llo CD4 T cells are heterogeneous with respect to CD27 expression and that CD27lo subset is the major source of IFN-γ in mice challenged with BCG or virulent M. tuberculosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice and infection

For BCG infection, 8–12 weeks old female C57BL/6 J (B6) mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME, USA) and maintained at the Trudeau Institute. Mice were housed in bonnet top cages, fed laboratory chow and given acidified water ad libitum. All studies were reviewed and approved by the Trudeau Institute IACUC. M. tuberculosis infection was performed at the Central Institute for Tuberculosis (CIT, Moscow, Russia). Age and sex-matched B6 mice were bred under conventional conditions at the Animal Facilities of the CIT in accordance with guidelines from the Russian Ministry of Health #755, NIH Office of Laboratory Animal Welfare (OLAW) Assurance #A5502-01. Water and food were provided ad libitum.

Mice were infected with either 106 CFUs of clump-free mid-log-phase M. bovis BCG Japan (TMC 1019; ATCC Manassas, VA, USA) or with 103 CFUs of clump-free mid-log-phase M. tuberculosis strain H37Rv Pasteur (initially, a kind gift of G.Marchal, Institute Pasteur, Paris, France). The choice of the doses was based on the results of preliminary experiments, which revealed that lower doses of BCG induced lower degree of T cell activation, which made T cell analysis and sorting difficult, while higher doses of M. tuberculosis induced acute lethal infection. Mycobacteria suspensions were prepared as described earlier [32,33] and were given intratracheally (i.t), unless indicated otherwise.

Flow cytometry analysis of lung cells

Suspensions of lung cells were obtained using an enzyme digestion method [19,32]. Briefly, lungs were perfused with 0·02% EDTA-PBS solution, incubated at 37°C for 1·5 h in supplemented RPMI-1640 medium containing 200 U/ml collagenase, and 50 U/ml DNAase-I (Sigma, St-Louis, MO, USA), and washed. Cells were stained with mAbs (BD, PharMingen) and analysed using a Becton Dickinson FACSCalibur with CellQuest (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) and FlowJo (San Carlos, CA, USA) softwares.

For intracellular cytokine staining, 1·5 × 106 cells were cultured in 24-well plates and stimulated with PPD (8 µg/ml, Mycos Research LLC Loveland, CO, USA) or with plastic-bound-anti-CD3 Mabs (clone 145–2C11, eBioscience) and anti-CD28 Mabs (clone 37·51eBioscience), or left unstimulated. Golgi-plug (1.5 µl/well, PharMingen) was added to the cultures 2–3 h later. After additional 10 h of culture, cells were stained using Cytofix/cytoperm kit (PharMingen) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Cell sorting and ELISPOT

Lung cells were enriched for CD4+ cells using mouse CD4 T cell subset columns (R & D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA), stained with FITC-anti-CD4, PE-anti-CD27, and APC-anti-CD62L, and sorted using a FACS Vantage with DIVA option (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA, USA). Two-fold dilutions of sorted or nonsorted responding cells, starting from 5 × 104 cells/well, were cultured in Elispot 96 well plates (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) coated with capture anti-IFN-γ Mabs (clone R46-A2, PharMingen). Syngeneic irradiated spleen cells (5 × 105 cells/well), rIL-2 (10 U/ml, R & D Systems) and PPD (8 µg/ml) were added to the cultures. Control wells contained sorted cells, antigen-presenting cells, and rIL-2 without addition of PPD. All cultures were performed in duplicate. IFN-γ producing cells were detected 24 h later using BD PharMingen anti-IFN-γ detecting mAbs (clone XM1·2, PharMingen), streptavidin-alkaline phosphatase and BCIP/NBT substrate. Spots on dry plates were counted, blinded, using a dissecting microscope.

In vivo BrdU incorporation assay

Assessment of BrdU incorporation was performed according to the method described by Winslow et al. [34] with some modifications. Briefly, suspensions of lung cells were obtained 24 h after intraperitoneal injection of mice with 1 mg of BrdU. Cells were stained with anti-CD4, anti-CD27, and anti-CD44 or anti-CD62L mAbs, treated with BD Lysing solution (PharMingen), and fixed/permeabilized with PBS, containing 1% formaldehyde and 0·1% Igepal (Sigma). After overnight incubation at 4°C and additional washing cells were treated with DNase, washed, stained with FITC-anti-BrdU Mabs (clone 3D4, PharMingen) or isotype control and analysed using the FACSCalibur cytometer as described above.

Real-time PCR

RNA was isolated from 105 nonsorted or sorted cells using a RNAqueous Micro Kit (Ambion, Austin, TX, USA). cDNA were prepared from 2 µg of the total RNA using random primers, 10 m m dNTP mix, RNaseOUT, and Superscript II RNase H- Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) following manufacturer's protocol. Taqman real-time PCR was performed using 2x Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) and IFN-γ or β2m primer/probe mix (Trudeau Institute MBCF, Saranac Lake, NY, USA). The housekeeping gene was chosen based on the results of preliminary experiments, which revealed a stable expression of β2m in control and infected lung tissue. Primers and probe for β2m housekeeping gene real-time PCR were designed by Doueck (Forward: TGACC GGCTTGTATGCTATC (66–115) Exon 1; reverse: CAGTGTG AGCCAGGATATAG (298–317) Exon2; probe: TATACTC ACGCCACCCACCGGAGAA (138–162) Exon 2 Tm = 68 Amplicon 223 NM_009735); for IFN-γ– by F = PSA:R,P = 1 (forward: CATTGAAAGCCTAGAAAGTCTGAATAAC (147–174) Exon 1; reverse: TGGCTCTGCAGGATTTTCATG (255–275) Exon 3; probe: TCACCATCCTTTTGCCAGTTCCTCCAG (228–246) Exon 2 (247–255) Exon 3 Amplicon 129 K00083). Eeach primer combination amplifies cDNA, but not genomic. cDNA was amplified using an ABI Prism 7000 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) following the manufacturers recommended protocol. IFN-γ mRNA expression levels by each subset of sorted cells was compared (1) to that of nonsorted cells or (2) to the expression of mRNA by the same subset of CD4+ cells isolated from control mice. Fold increase of mRNA expression was calculated as follows: (1) fold increase = 2–(∧Ct sorted–∧Ct nonsorted); (2)fold increase = 2−(∧Ct infected–∧Ct control); where ∧Ct = Ct (IFN-γ) – Ct (β2m).

Statistical analysis

Significance of the differences was estimated by Tukey-test. P < 0·05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Lung CD4+ T cells with effector/memory CD44hiCD62Llo phenotype are heterogeneous with respect to CD27 expression

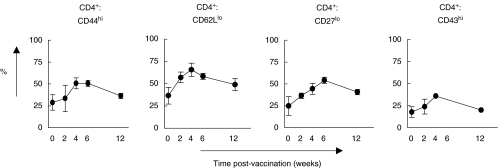

In accordance with previous data [14,22], BCG infection induced accumulation in the lungs of CD4+ T cells with an effector/memory CD44hi CD62Llo phenotype. These cells increased from about 20–30% at week 0 to 50-70% at week 4 (peak of the response) and declined by week 12 postinfection (Fig. 1). Expression of surface molecules other than CD44 and CD62L on CD4+ T cells also changed and CD4+ T cells with up-regulated CD29, CD49d, and CD43 and down-regulated CD27 expression accumulated in the lungs (Fig. 1 and data not shown).

Fig. 1.

Activated CD4+ T cells transiently accumulate in the lungs of BCG infected mice. Suspensions of lung cells were isolated from the lungs of control (week 0) or BCG-infected mice, and stained with PerCP-anti-CD4 mAbs combined with: FITC-anti-CD44, FITC-anti-CD43, or FITC-anti-CD29; PE-anti-CD27 or PE-anti-CD49d; and APC-anti-CD62L mAbs. Cells were analysed by Flow cytometry (2–3 independent experiments, 2–4 mice analysed individually per group per time-point in each experiment).

CD27 is a transmembrane homodimeric molecule that belongs to the TNF/nerve factor receptor family [35]. It plays a role in T cell differentiation by providing naive T cells with costimulatory signals [35–38]. Therefore, down-modulation of CD27 could mark a step in T cell differentiation at a point in which these cells become independent from further costimulation. Thus, we focused our studies on the analysis of CD27 expression and determined whether and how down-regulation of CD27 was related to the up- and down-modulation of CD44 and CD62L expression and to the functional activity of CD4+ T cells.

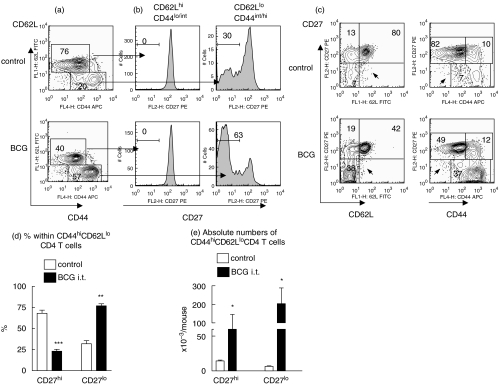

Simultaneous staining of lung CD4+ T cells for CD44, CD62L, and CD27 surface expression revealed that cells with down-regulated CD62L expression usually had a CD44int/hi phenotype (Fig. 2a). Further, lung CD4+ T cells bearing a CD44lo/intCD62Lhi phenotype (‘naive/resting’ T cells) were all homogenous and expressed high levels of CD27. In contrast, cells expressing CD44hi/intCD62Llo phenotype (effector/memory cells) were heterogeneous and consisted of both CD27hi and CD27lo subsets (Fig. 2b). Finally, T cells with down-modulated CD27 expression always exhibited a CD62Llo and CD44hi phenotype with no substantial subsets of CD27loCD62Lhi and CD27loCD44lo cells being detected within CD4+ cells (Fig. 2c, arrows).

Fig. 2.

Heterogeneity of CD44hiCD62Llo lung CD4+ T cells with respect to CD27 expression and accumulation of CD27lo subset in the lungs during BCG infection. Lung cells from individual control or BCG challenged mice were stained with FITC-anti-CD44, PE-anti-CD27, PerCP-anti-CD4, and APC-anti-CD62L mAbs. (a, c) Representative patterns of CD44 versus CD62L (a), CD62L versus CD27, and CD44 versus CD27 (c) expression by CD4+ T cells. (b) CD27 expression by distinct subsets of CD4+ T cells. Cells were obtained from the lungs of the same mouse, as in (a, c). Histograms were generated after gating on the indicated subsets of CD4+ T cells. (d, e) Percentages (d) and absolute numbers (e) of CD27hi and CD27lo subsets of CD44hiCD62Llo cells in the lungs. Depicted are results of one out of 3 independent experiments performed at week 2 post challenge with BCG (▪) (3 mice per group per experiment analysed individually). Control (□) Similar results were obtained at week 4. *P < 0·05; **P < 0·01; ***P < 0·001.

The heterogeneity of CD44hiCD62Llo CD4+ T cells with respect to the levels of CD27 expression was a characteristic feature of lung cells and was detected irrespective of whether mice were infected with BCG or not (Fig. 2b). However, the proportion between CD27hi and CD27lo subsets of effector/memory CD4+ T cells significantly changed during the acute phase of BCG infection. In control mice, a majority of lung CD44hiCD62Llo CD4+ T cells were CD27hi, while in mice infected with BCG, 77 ± 2·4% of CD44hi/intCD62Llo CD4+ T cells were CD27lo (Figs 2b,d). It should be emphasized that absolute numbers of both, CD27lo and CD27hi subsets of CD44hi/intCD62Llo cells increased in the lungs of mice challenged with BCG (Fig. 2e). Thus, at least some of CD44hi/intCD62Llo CD4+ cells with CD27hi phenotype did not preexist in the lungs, but accumulated there in response to the infection.

We next addressed the question of whether and how functional activity of CD27loCD44hiCD62Llo cells, capacity to secrete IFN-γ, in particular, differed from that of CD27hiCD44hiCD62Llo cells.

The CD27lo subset of CD44hiCD62Llo CD4+ T cells is the major source of IFN-γ in BCG-infected mice

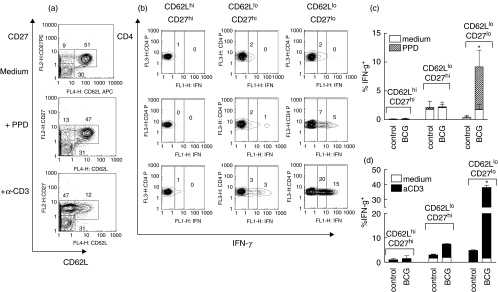

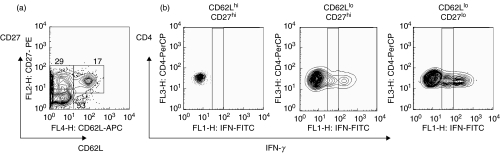

First, lung cells isolated from control and BCG-infected mice were stimulated in vitro with PPD or anti-CD3 mAbs and assessed for intracellular levels of IFN-γ. As we were restricted to 4-colour staining and given that CD44 up- and CD62L down-regulation during a primary T cell response are closely related (Fig. 2a), we stained cells with anti-CD4, anti-CD27, and anti-IFN-γ plus anti-CD44 or anti-CD62L mAbs. As an example, results obtained with anti-CD62L mAbs are shown on Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Cells producing IFN-γ in response to stimulation in vitro belong to CD27lo subset of CD62Llo cells. Lung cell suspensions were obtained from control or BCG- infected mice and stimulated in vitro with PPD; plate-bound anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 mAbs; or were left unstimulated. After overnight culture in the presence of brefeldin, cells were harvested and stained with labelled mAbs. (a) CD62L and CD27 expression by lung cells isolated from BCG challenged mouse and cultured in vitro in different conditions (pictures were generated after gating on CD4+ cells). Note down-regulation of CD62L by T cells stimulated via CD3 receptor. (b) Typical staining for the IFN-γ after gating on distinct subsets of CD4+ T cells (the same cells as in (a)). (c, d) Percentages of IFN-γ producing cells within distinct subsets of lung CD4+ T cells stimulated with PPD or via CD3 receptor (summarized results). Data are mean ± SD from 2 independent experiments performed at week 2 postinfection (total of 6–10 mice per group analysed individually). At week 4 postinfection similar results were obtained. *P < 0·05 as compared to cells isolated from control mice.

Similar to results obtained using ex vivo isolated CD4+ T cells, cultured cells formed three major subsets: CD62LhiCD27hi, CD62LloCD27hi, and CD62LloCD27lo (Fig. 3a). Among these subsets, only cells with down-regulated CD27 expression produced IFN-γ in response to PPD stimulation (Figs 3b,c). When cells were stimulated through the CD3 receptor, CD27lo cells were also the major IFN-γ producers, however, IFN-γ production by CD62LloCD27hi cells was also detected (Figs 3b,d). Importantly, incubation of T cells with immobilized anti-CD3 mAbs induced significant down-regulation of CD62L (for control mice percentage of CD62Llo cells in unstimulated cultures and cultures stimulated with anti-CD3/anti-CD28 mAbs were 24·6 ± 2·4% and 75·1 ± 3·7%, respectively, P < 0·001; see also Fig. 3a for BCG infected mice), but it did not alter the pattern of CD27 expression, indicating that CD27 expression was a more stable marker of T cell differentiation.

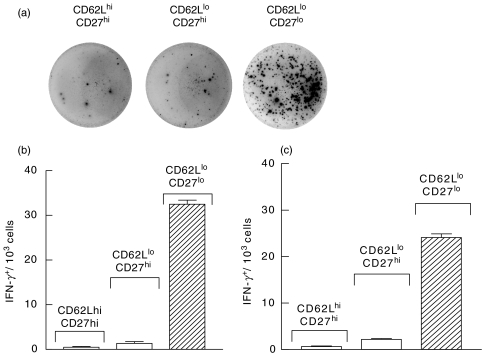

To directly show that correlation between down-modulation of CD27 expression and IFN-γ production was not an in vitro artifact we determined the frequencies of IFN-γ producing cells in distinct subsets of ex vivo isolated lymphocytes. CD4+ T cells were isolated from the lungs of mice infected with BCG i.t and sorted into CD62LhiCD27hi, CD62LloCD27hi, and CD62LloCD27lo subsets. ELISPOT analysis of sorted cells revealed that the frequency of IFN-γ-producing cells was at least 30-fold higher within the CD27lo than within the CD27hi subset of CD62Llo lung T cells (Figs 4a,b).

Fig. 4.

CD62Llo CD4+ T cells with CD27lo, but not CD27hi phenotype, are the major cells producing IFN-γ as detected by Elispot assay. Mice were challenged with BCG i.t. (a, b) or i.v. (c). Cells were isolated from the lungs (a, b) or spleen (c) 3 weeks later, stained with FITC-anti-CD4, PE-anti-CD27, and APC-anti-CD62L mAbs, and sorted. Sorted cells were cultured at different concentrations in the presence of syngeneic irradiated spleen cells and PPD and frequencies of IFN-γ-producing cells were determined using ELISPOT assay. (a) Pictures of representative wells, in which 2·5 × 104 lung cells of indicated phenotype were cultured. (b, c) Frequencies of IFN-γ producing cells within distinct subsets of CD4+ T cells isolated from the lungs of mice infected with BCG i.t. (b) or from the spleen of mice infected with BCG i.v. (c). In the absence of PPD numbers of IFN-γ-producing cells were equal to those in CD62Lhi subset and never exceeded 1/103 (data not shown).

To further substantiate our findings, we determined expression levels of mRNA for IFN-γ by distinct subsets of CD4+ T cells. Because it is difficult to collect enough numbers of rare subset cells from the lung, we used spleen of control mice or mice challenged with BCG i.v. as a source of cells in these experiments. Preliminary data indicated that spleen CD4 T cells exhibited similar patterns of CD27/CD62L and CD27/CD44 coexpression (data not shown) and that spleen IFN-γ producing cells also belonged mainly to CD27lo subset of CD4+ T cells (Fig. 4c). Thus, spleen cells were sorted into CD62LhiCD27hi, CD62LloCD27hi, and CD62LloCD27lo subsets, and RNA isolated from nonsorted or sorted cells was analysed by Taqman RT-PCR. Data presented in Table 1, demonstrate that CD27lo subset of CD62Llo cells exhibited much higher increase in the content of IFN-γ RNA as compared to CD27hi subset.

Table 1.

Expression of IFN-γ mRNA by spleen CD4+ cells is highest within CD62LloCD27lo subset

| CD62Lhi CD27hi | CD62Llo CD27hi | CD62Llo CD27lo | |

|---|---|---|---|

| A (as compared to nonsorted cells) | 0·4 | 6·5 | 40·5 |

| B (as compared to control mice) | 0·5 | 3·8 | 18·4 |

Cells were isolated from spleens of control or BCG-infected mice (4 weeks after BCG infection via the i.v. route). Cells from 5 mice were pooled, stained with FITC-anti-CD4, PE-anti-CD27, and APC-anti-CD62L mAbs, and sorted. mRNA was isolated from 105 sorted or nonsorted cells and analysed for expression of IFN-γ by Taqman assay. IFN-γ mRNA expression levels by each subset of sorted cells isolated from infected mice was compared: (A) to that of nonsorted cells isolated from the same mice: fold increase = 2−(^Ct sorted–^Ct nonsorted); (B) to the expression of mRNA by the same subset of CD4+ cells isolated from control mice: fold increase = 2−(^Ct infected–^Ct control). ^Ct = Ct (IFN-γ) – Ct (β2m).

CD44hiCD62Llo CD4 T cells exhibit proliferative activity in vivo irrespective of CD27 expression

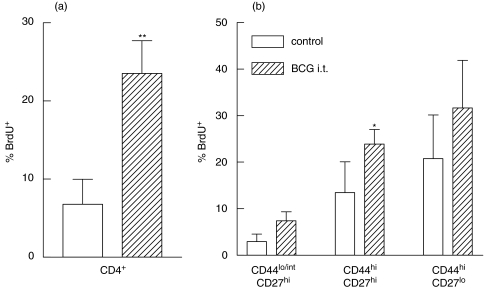

We next studied, whether CD27hi and CD27lo subsets of effector/memory CD4+ T cells differed by their proliferative activity in vivo. Control and BCG infected mice received a BrdU pulse and BrdU incorporation by different subsets of CD4+ lung T cells was determined 24 h later. BCG-induced proliferation of CD4+ T cells was observed at week 2 (Fig. 5a) and declined by week 4 (data not shown) postinfection, which generally corresponds to the results of other authors [34].

Fig. 5.

CD4+ cells proliferating in vivo in response to BCG have up-regulated CD44 expression, but do not differ by the expression of CD27. Control (□) and BCG-infected ( ) mice were pulsed with BrdU at week 2 postinfection. 24 h later lung cells were stained with FITC-anti-BrdU, PE-anti-CD27, PerCP-anti-CD4 and APC-anti-CD44 mAbs and analysed by Flow cytometry. (a) Percent of BrdU+ cells within CD4+ subset of lung cells. (b) Percent of BrdU+ cells within subsets of CD4+ T cells with different expression of CD44 and CD27 molecules. Data are mean ± SD from 2 independent experiments (total of 6 mice per group analysed individually). *P < 0·05; **P < 0·01; as compared to control mice.

) mice were pulsed with BrdU at week 2 postinfection. 24 h later lung cells were stained with FITC-anti-BrdU, PE-anti-CD27, PerCP-anti-CD4 and APC-anti-CD44 mAbs and analysed by Flow cytometry. (a) Percent of BrdU+ cells within CD4+ subset of lung cells. (b) Percent of BrdU+ cells within subsets of CD4+ T cells with different expression of CD44 and CD27 molecules. Data are mean ± SD from 2 independent experiments (total of 6 mice per group analysed individually). *P < 0·05; **P < 0·01; as compared to control mice.

Proliferation was tightly associated with up-regulation of CD44 (Fig. 5b) and down-regulation of CD62L (data not shown), but did not depend significantly on the level of CD27 expression (Figs 5b; P < 0·001 for CD44hiversus CD44lo comparison and P > 0·05 for CD44hiCD27loversus CD44hiCD27hi comparison). Interestingly, only minor differences between control and BCG infected mice were revealed when BrdU incorporation within each subset of CD4+ cells was analysed. This can be explained if one assumes that in vivo proliferation of CD4+ T cells is closely related to the stage of T cell differentiation and that each subset of CD4+ T lymphocytes sustains a relatively stable rate of proliferation. Higher levels of CD4+ T cell proliferation in BCG-infected compared with control mice were therefore due to the higher proportion of CD44hiCD62LloCD27hi and ‘highly differentiated’ CD44hiCD62LloCD27lo cells accumulating in the lungs of infected mice.

Cells producing IFN-γ in response to M. tuberculosis infection also belong to CD27lo subset

IFN-γ is a key cytokine for protection against TB. Therefore we next analysed whether CD4+T cells producing IFN-γ during M. tuberculosis infection also belonged to CD27lo subset. Figure 6 demonstrates that in accordance with data obtained following challenge of mice with BCG, effector CD44hiCD62Llo CD4+ T cells accumulating in the lungs during M. tuberculosis infection were also heterogeneous with respect to the CD27 expression (Fig. 6a) and that IFN-γ producers were basically found within the CD27lo subset of effector CD4 T cells (Fig. 6b).

Fig. 6.

CD27lo subset of lung CD62Llo CD4 T cells is the major source of IFN-γ during infection with virulent M. tuberculosis. Lung cells were obtained from control mice (data not shown) or mice infected with M. tuberculosis strain H37Rv 3 weeks prior the experiment. Cells were stimulated with H37Rv sonicate (8 µg/ml), cultured in the presence of brefeldin, stained and analysed by Flow cytometry (see Legend to Fig. 3 for details). No significant production of IFN-γ was detected in cells isolated from control mice.

Together our results indicate that CD4+ T cells bearing the phenotype of effector/memory cells are heterogeneous and that during acute mycobacterial infections IFN-γ is produced mainly by the CD27lo subset of these cells. Thus, the CD27lo population can be considered a subset of highly differentiated effector CD4+ T cells with high potential for mediating protection against TB.

DISCUSSION

CD4 T cells bearing CD44hiCD62Llo phenotype are usually considered as effector/memory cells. We have found CD44hiCD62Llo CD4 T cells accumulating in the lungs in response to mycobacterial infection, do not form a homogenous population and basing on their surface phenotype, can be divided into two subsets, CD27hi and CD27lo. Irrespectively of the levels of CD27 expression, all CD44hiCD62Llo CD4 T cells display high levels of proliferation in vivo, but capacity to secrete IFN-γ upon antigenic stimulation is mainly associated with only one (CD27lo) subset of these cells. In addition, our recent data indicate that CD27lo subset of CD4+ T cells preferentially accumulates in the lungs but not in the lymph nodes of BCG challenged mice (manuscript in preparation). Thus, the CD27lo subset of CD44hiCD62Llo cells likely represents a subset of highly differentiated effector T cells which in some ways resemble ‘effector memory’ cells according to the classification proposed by Lanzavecchia and colleagues [39]. Indeed, effector memory cells were characterized by residence in tertiary tissues and high capacity for IFN-γ production. Several attempts to correlate effector functions, IFN-γ production in particular, with a certain surface phenotype of T cells have recently been performed by different investigators. Association of IFN-γ production with CD4 or CD8 T cells expressing CD44hi [22,40], CD44hiCD62LloCD45RBint [41], CD45RA–CD62L–CD11ahi [42], and β1+ [20] phenotype has been reported. This, however, is not surprising, as up-regulation of CD44 is known to occur very early during the T cell differentiation process and down-regulation of CD62L, as well as up-regulation of integrins, are needed for T cell migration to the inflamed periphery sites. Our results correspond well to these data as CD27lo cells uniformly expressed CD44hiCD62Llo phenotype. However, we have extended these observations by demonstrating that acquisition of effector/memory CD44hiCD62Llo phenotype does not necessarily correlate with capacity for IFN-γ secretion and that only CD27lo subset of these cells have high potential for IFN-γ secretion.

Association between loss of CD27 expression and acquisition of effector function has earlier been reported for CD8+ T cells, in particular for human virus-specific cells. CD8+ T cells bearing CD27lo phenotype were shown to express high levels of perforin, granzyme, and Fas-ligand and to synthesize IFN-γ and TNF-α [43,44]. Recently these observations were extended for human Vγ9+Vβ2+ T cells [45]. To our knowledge, our data represent the first demonstration of similar relationships between CD27 down-modulation and capacity for IFN-γ secretion in CD4+ T cells – the major protecting cells against mycobacterial infections.

In contrast to IFN-γ production, in vivo proliferation of T cells correlated more with CD44 up- and CD62L-down-regulation than with loss of CD27 expression. This contradicts the results obtained by others who reported that less differentiated (CD27hi) CD8+ or γδ T cells proliferated at a greater rate when compared with more differentiated (CD27lo) cells [43,45]. However, in these studies proliferation of cells was analysed in vitro, following stimulation with nonspecific agents (anti-CD3 mAbs or isopentenyl pyrophosphate). Our data were obtained in vivo and during chronic bacterial infection. In such circumstances, persistent stimulation of T cells with mycobacterial antigens could induce proliferation even when cells were highly differentiated. Alternatively, cells that had incorporated BrdU could acquire CD27lo phenotype as a result of their proliferation.

Our studies were performed during the acute phase of the antimycobacterial response. An interesting question to address is how stable down-regulation of CD27 expression by CD4 T cells is and what are the relationships between CD27hi and CD27lo subsets of CD44hiCD62Llo cells. We hypothesize that CD27lo CD4 T cells represent highly differentiated CD4 T cells deriving from ‘intermediate’ effectors with CD62LloCD27hi phenotype. At least, for CD8 T cells, differentiation from CD27+ to CD27– cells has been suggested [43]. On the other hand, conversion from CD27lo to CD27hi cells is also possible and was recently demonstrated for CD8 T cells in the absence of antigenic stimulation [46]. Whether similar conversion can occur during antimycobacterial response of CD4 T cells remains to be established. Indeed, differentiation of CD4 T cells can differ from that of CD8 cells. In addition, during chronic infections terminal differentiation of effector T cells rather than their conversion to memory subset can take place. At least apoptosis of IFN-γ-producing effector CD4 T cells during BCG infection [47] and inability of IFN-γ-producing cells to give rise to memory cells [48] have been demonstrated. In conclusion, we propose that CD44hiCD62LloCD27lo CD4 T cells described in our paper represent highly differentiated effector cells generated during chronic mycobacterial infection and possessing high capacity for IFN-γ secretion. Experiments to clarify whether protection against M. tuberculosis infection can be transferred to the host by CD27lo CD4 T cells are now ongoing.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr S. Monard for help with cell sorting and Flow cytometry analysis and Dr S. Adams for help with real-time PCR experiments. This work was supported with funding provided by the Sequella Global Tuberculosis Foundation, The American Lung Association, Trudeau Institute, Inc, and partially, by Russian Foundation for Basic Research.

REFERENCES

- 1.Colditz GA, Brewer TF, Berkey CS, Wilson ME, Burdick E, Fineberg HV, Mosteller F. Efficacy of BCG vaccine in the prevention of tuberculosis. Meta-analysis of the published literature. J Am Med Assoc. 1981;271:698–702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.North RJ. Importance of thymus-derived lymphocytes in cell-mediated immunity to infection. Cell Immunol. 1973;7:166–76. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(73)90193-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Orme IM, Collins FM. Protection against Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection by adoptive immunotherapy. Requirement for T cell-deficient recipients. J Exp Med. 1983;158:74–83. doi: 10.1084/jem.158.1.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Flynn JL, Goldstein MM, Triebold KJ, Koller B, Bloom BR. Major histocompatibility complex class I-restricted T cells are required for resistance to Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:12013–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.24.12013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.D’Souza CD, Cooper AM, Frank AA, Mazzaccaro RJ, Bloom BR, Orme IM. An. anti-inflammatory role for gamma delta T lymphocytes in acquired immunity to Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Immunol. 1997;158:1217–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mogues T, Goodrich ME, Ryan L, LaCourse R, North RJ. The relative importance of T cell subsets in immunity and immunopathology of airborne Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in mice. J Exp Med. 2001;193:271–80. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.3.271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saunders BM, Frank AA, Orme IM, Cooper AM. CD4 is required for the development of a protective granulomatous response to pulmonary tuberculosis. Cell Immunol. 2002;216:65–72. doi: 10.1016/s0008-8749(02)00510-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cooper AM, Dalton DK, Stewart TA, Griffin JP, Russell DG, Orme IM. Disseminated tuberculosis in interferon gamma gene-disrupted mice. J Exp Med. 1993;178:2243–7. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.6.2243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Flynn JL, Chan J, Triebold KJ, Dalton DK, Stewart TA, Bloom BR. An essential role for interferon gamma in resistance to Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. J Exp Med. 1993;178:2249–54. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.6.2249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.MacMicking JD, North RJ, LaCourse R, Mudgett JS, Shah SK, Nathan CF. Identification of nitric oxide synthase as a protective locus against tuberculosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:5243–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.10.5243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jouanguy E, Doffinger R, Dupuis S, Pallier A, Altare F, Casanova J. IL-12 and IFN-γ in host defense against mycobacteria and salmonella in mice and men. Curr Opin Immunol. 1999;11:346–51. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(99)80055-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Collins HL, Kaufmann SHE. The many faces of host response to tuberculosis. Immunology. 2001;103:1–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2001.01236.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eruslanov EB, Majorov KB, Orlova MO, Mischenko VV, Kondratieva TK, Apt AS, Lyadova IV. Lung responses to M. tuberculosis in genetically susceptible and resistant mice following intratracheal challenge. Clin Exp Immunol. 2004;135:19–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2004.02328.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lyadova IV, Vordermeier HM, Eruslanov EB, Khaidukov SV, Apt AS, Hewinson RG. Intranasal BCG vaccination protects BALB/c mice against virulent Mycobacterium bovis and accelerates production of IFN-γ in their lungs. Clin Exp Immunol. 2001;126:274–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2001.01667.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen L, Wang J, Zganiacz A, Xing Z. Single intranasal mucosal Mycobacterium bovis BCG vaccination confers improved protection compared to subcutaneous vaccination against pulmonary tuberculosis. Infect Immun. 2004;72:238–46. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.1.238-246.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hu H, Huston G, Duso D, Lepak N, Roman E, Swain SL. CD4+ T cell effectors can become memory cells with high efficiency and without further division. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:705–10. doi: 10.1038/90643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Griffin JP, Orme IM. Evolution of CD4 T-cell subsets following infection of naive and memory immune mice with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect Immun. 1994;62:1683–90. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.5.1683-1690.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feng CG, Bean AGD, Hooi H, Briscoe H, Britton WJ. Increase in gamma interferon-secreting CD8+, as well as CD4+, T cells in lungs following aerosol infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect Immun. 1999;67:3242–7. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.7.3242-3247.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lyadova IV, Eruslanov EB, Yeremeev VV, et al. Comparative analysis of T lymphocytes recovered from the lungs of mice genetically susceptible, resistant and hyperresistant to Mycobacterium tuberculosis-triggered disease. J Immunol. 2000;165:5921–31. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.10.5921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Palendira U, Bean AGD, Feng CG, Britton WJ. Lymphocyte recruitment and protective efficacy against pulmonary mycobacterial infection are independent of the route of prior Mycobacterium bovis BCG immunization. Infect Immun. 2002;70:1410–6. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.3.1410-1416.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Junqueira-Kipnis AP, Turner J, Gonzalez-Juarrero M, Turner OC, Orme IM. Stable T-cell population expressing and effector cell surface phenotype in the lungs of mice chronically infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect Immun. 2004;72:570–5. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.1.570-575.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Silva CL, Bonato VLD, Lima VMF, Faccioli LH, Leac SC. Characterization of the memory/activated T cells that mediate the long-lived host response against tuberculosis after bacillus calmette-Guerin or DNA vaccination. Immunology. 1999;97:573–81. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1999.00840.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang X, Mosmann T. In vivo priming of CD4 T cells that produce interleukin (IL) -2 but not IL-4 or interferon (IFN) -gamma, and can subsequently differentiate into IL-4- or IFN-gamma-secreting cells. J Exp Med. 2001;194:1069–80. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.8.1069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bird JJ, Brown DR, Mullen AC, et al. Helper T cell differentiation is controlled by the cell cycle. Immunity. 1998;9:229–37. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80605-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gudmundsdottir H, Wells AD, Turka LA. Dynamics and requirements of T cell clonal expansion in vivo at the single-cell level: effector function is linked to proliferative capacity. J Immunol. 1999;162:5212–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Laouar Y, Crispe IN. Functional flexibility in T cells. independent regulation of CD4+ T cell proliferation and effector function in vivo. Immunity. 2000;13:291–301. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)00029-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ben-Sasson SZ, Gerstel R, Hu-Li J, Paul WE. Cell division is not a ‘clock’ measuring acquisition of competence to produce IFN-gamma or IL-4. J Immunol. 2001;166:112–20. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.1.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mannering SI, Cheers C. Interleukin-2 and loss of immunity in experimental Mycobacterium avium infection. Infect Immun. 2002;70:27–35. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.1.27-35.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hengel RL, Thaker V, Pavlick MV, Metcalf JA, Dennis G, Jr, Yang J, Lempicki RA, Sereti I, Lane HC. 1-selectin (CD62L) expression distinguishes small resting memory CD4+ T cells that preferentially respond to recall antigen. J Immunol. 2003;170:28–32. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.1.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hogan RJ, Zhong W, Usherwood EJ, Cookenham T, Roberts AD, Woodland DL. Protection from respiratory virus infections can be mediated by antigen-specific CD4+ T cells that persist in the lungs. J Exp Med. 2001;193:981–6. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.8.981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roman E, Miller E, Harmsen A, Wiley J, von Adrian UH, Huston G, Swain SL. CD4 effector T cell subsets in the response to influenza. heterogeneity, migration, and function. J Exp Med. 2002;196:957–68. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lyadova IV, Yeremeev VV, Majorov KB, Nikonenko BV, Khaidukov SV, Kondratieva TK, Kobets NV, Apt AS. An ex vivo study of T lymphocytes recovered from the lungs of I/St mice infected with and susceptible to Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect Immun. 1998;66:4981–8. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.10.4981-4988.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nikonenko BV, Averbakh MM, Jr, Lavebratt C, Schurr E, Apt AS. Comparative analysis of mycobacterial infections in susceptible I/St and resistant A/Sn inbred mice. Tubercule Lung Dis. 2000;80:15–25. doi: 10.1054/tuld.1999.0225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Winslow GM, Roberts AD, Blackman MA, Woodland DL. Persistence and Turnover of Antigen-specific CD4 T cells during Chronic Tuberculosis Infection in the Mouse. J Immunol. 2003;170:2046–52. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.4.2046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kobata T, Agematsu K, Kameoka J, Schlossman SF, Morimoto C. CD27 is a signal-transducing molecule involved in CD45RA+ naive T cell costimulation. J Immunol. 1994;153:5422–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Arens R, Tesselaar K, Baars PA, et al. Constitutive CD27/CD70 interaction induces expansion of effector-type T cells and results in IFN-γ-mediated B cell depletion. Immunity. 2001;15:801–12. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00236-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tesselaar K, Arens R, van Schijndel GMW, Baars PA, van der Valk MA, Borst J, van Oers MHJ, van Lier RAW. Lethal T cell immunodeficiency induced by chronic costimulation via CD27–CD70 interactions. Nature Immunol. 2003;4:49–54. doi: 10.1038/ni869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hendriks J, Xiao Y, Borst J. CD27 promotes survival of activated T cells and complements CD28 in generation and establishment of the effector T cell pool. J Exp Med. 2003;198:1369–80. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sallusto F, Lenig D, Forster R, Lipp M, Lanzavecchia A. Two subsets of memory T lymphocytes with distinct homing potentials and effector functions. Nature. 1999;401:708–12. doi: 10.1038/44385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Serbina NV, Flynn JL. Early emergence of CD8+ T cells primed for production of type 1 cytokines in the lungs of Mycobacterium tuberculosis-infected mice. Infect Immun. 1999;67:3980–8. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.8.3980-3988.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Andersen P, Smedegaard B. CD4+ T-cell subsets that mediate immunological memory to Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in mice. Infect Immun. 2000;68:621–9. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.2.621-629.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mitra DK, De Rosa SC, Luke A, et al. Differential representations of memory T cell subsets are characteristic of polarized immunity in leprosy and atopic diseases. Intern Immunol. 1999;11:1801–10. doi: 10.1093/intimm/11.11.1801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Appay V, Dunbar PR, Callan M, et al. Memory CD8+ T cells vary in differentiation phenotype in different persistent virus infection. Nature Med. 2002;8:379–85. doi: 10.1038/nm0402-379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hamann D, Baars PA, Rep MHG, Hooibrink B, Kerkhof-Garde SR, Klein MR, van Lier RAW. Phenotypic and functional separation of memory and effector CD8+ T cells. J Exp Med. 1997;186:1407–18. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.9.1407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gioia C, Agrati C, Casetti R, et al. Lack of CD27–CD45RA–Vγ9Vδ2+ T cell effectors in immunocompromised hosts and during active pulmonary tuberculosis. J Immunol. 2002;168:1484–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.3.1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wherry EJ, Teichgräber V, Becker TC, Masopust D, Kaech SM, Antia R, von Adrian UH, Ahmed R. Lineage relationship and protective immunity of memory CD8 Tcell subsets. Nature Immunol. 2003;4:225–34. doi: 10.1038/ni889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dalton DK, Haynes L, Chu CQ, Swain SL, Wittmer S. Interferon gamma eliminates responding CD4 T cells during mycobacterial infection by inducing apoptosis of activated CD4 T cells. J Exp Med. 2002;192:117–22. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.1.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wu C, Kirman JR, Rotte MJ, et al. Distinct lineages of TH1 cells have differential capacities for memory cell generation in vivo. Nature Immunol. 2002;3:852–8. doi: 10.1038/ni832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]