Abstract

Severe thrombocytopenia and increased vascular permeability are two major characteristics of dengue haemorrhagic fever (DHF). To develop a better understanding of the roles of platelet-associated IgG (PAIgG) and IgM (PAIgM) in inducing thrombocytopenia and its severity of disease in patients with secondary dengue virus infection, the relationship between the PAIgG or PAIgM levels and disease severity as well as thrombocytopenia was examined in 78 patients with acute phase secondary infection in a prospective hospital-based study. The decrease in platelet count during the acute phase recovered significantly during the convalescent phase. In contrast, the increased levels of PAIgG or PAIgM that occurred during the acute phase of these patients decreased significantly during the convalescent phase. An inverse correlation between platelet count and PAIgG or PAIgM levels was found in these patients. Anti-dengue virus IgG and IgM activity was found in platelet eluates from 10 patients in an acute phase of secondary infection. Increased levels of PAIgG or PAIgM were significantly higher in DHF than those in dengue fever (DF). An increased level of PAIgM was associated independently with the development of DHF, representing a possible predictor of DHF with a high specificity. Our present data suggest that platelet-associated immunoglobulins involving antidengue virus activity play a pivotal role in the induction of thrombocytopenia and the severity of the disease in secondary dengue virus infections.

Keywords: dengue haemorrhagic fever, PAIgG, PAIgM, secondary infection, thrombocytopenia

INTRODUCTION

The dengue virus, a mosquito-borne human viral pathogen, is recognized increasingly as a major public health issue in tropical and subtropical countries, particularly in urban and peri-urban areas [1]. Approximately 2·5 billion people in more than 100 countries are currently at risk of infection, with an estimated 50 million infections per year [2]. The four serotypes of dengue virus induce a wide spectrum of clinical manifestations, which are associated frequently with haemorrhagic diathesis [3]. While dengue fever (DF) is a self-limited febrile illness, dengue haemorrhagic fever (DHF) is characterized by prominent haemorrhagic manifestations associated with thrombocytopenia and an increased vascular permeability. Secondary infections, which are observed commonly in the dengue-endemic areas, are more likely to constitute a risk factor for DHF [4–6].

While dengue virus-induced bone marrow suppression decreases platelet synthesis [7], an immune mechanism of thrombocytopenia due to increased platelet destruction appears to be operative in patients with DHF [8,9]. An increased level of PAIgG is observed frequently in patients with chronic idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP), but is also found in a variety of diseases [10–12]. Although virus-associated ITP such as human herpesvirus 6 infection has also been recognized [13–15], the association of increased levels of PAIgG and the mechanisms of PAIgG-mediated thrombocytopenia has been poorly examined in these viral infections.

We demonstrated recently an inverse correlation between the levels of platelet-associated IgG (PAIgG) and platelet count during the acute phase of secondary dengue infections [16]. The circulating antiplatelet autoantibody was rarely detected in this study. We speculated that immune complexes of the dengue virus with antidengue virus IgG antibodies are located on the platelet via the direct binding of the dengue virus to platelets [17]. The findings shown in this study suggest that PAIgG formation involving antidengue virus IgG plays an important role in inducing thrombocytopenia in secondary infections.

Because thrombocytopenia is more prominent in DHF than in DF [3], we hypothesized that the increased level of PAIgG might be associated with the severity of the disease as well as thrombocytopenia. In addition, the role of platelet-associated IgM (PAIgM) remains uncertain in this disease, although the level of antidengue virus IgM is also elevated in the sera of patients with secondary infections [18]. In this study, we therefore report on a prospective hospital-based study to examine whether the levels of PAIgG or PAIgM correlated with the disease severity as well as thrombocytopenia in patients with secondary infections. We demonstrate here the possible role of platelet-associated immunoglobulins in the development of thrombocytopenia and disease severity in secondary dengue virus infections.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients and study design

One hundred and thirty-five patients clinically suspected of having a dengue virus infection were enrolled at San Lazaro Hospital between September 2002 and November 2003. Of these subjects, 102 patients were diagnosed with the acute phase of dengue virus infection (3–7 days after the onset of illness) as evidenced by IgM-capture enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) or reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) [19,20]. Of these patients, 97 were diagnosed with the acute phase of a secondary dengue infection (3–7 days after the onset of illness) by a haemagglutination inhibition (HI) test. Five were diagnosed as having a primary dengue infections by the HI test. Among 97 patients with a secondary dengue infection, we evaluated 78 patients who were examined for platelet count and PAIgG and PAIgM levels at the time of enrolment (acute phase) and 4 days after the first test (convalescent phase) in this study. The levels of PAIgM were not determined in three samples in the acute phase and one sample in the convalescent phase because of the insufficient volume obtained. Forty-three age-matched healthy volunteers were also enrolled as control subjects at St Luke's Medical Center during the same period, and were examined for the IgM capture ELISA for the dengue virus, platelet count, PAIgG and PAIgM levels at the time of enrolment. EDTA blood was drawn from patients and healthy volunteers for these tests. The platelet count was determined with an automatic haemocytometer. DHF was diagnosed by World Health Organization (WHO) criteria; a platelet count nadir of less than 100 000/µl, haemorrhagic manifestations and an increase in haematocrit equal to or greater than 20% above the average of age group or the presence of pleural effusion or ascites fluid [21]. Cases of DHF were further graded as I–IV. DF was defined as an increase in haematocrit of less than 20% and no detectable pleural effusion on the right lateral decubitus chest radiograph [22].

The study protocol was approved by the Bioethics Committee of San Lazaro Hospital and the St Luke's Medical Center. Parents or guardians of all patients and healthy volunteers provided written informed consent.

HI test

An HI test was performed using a paired plasma sample with an interval longer than 7 days by the method of Clarke and Casals [23]. Four haemagglutinating units of dengue-1 (99 St-12 A strain), dengue 2 (00St-22 A strain), dengue-3 (SLMC 50 strain) and dengue-4 (SLMC 318 strain) acetone-extracted antigens were used in this test. When an HI titre ≥1 : 2560 in plasma from the patient with acute or convalescent phase was found, the case was considered to be a secondary infection [21].

Competitive ELISA for PAIgG and PAIgM

The wells of flat-bottomed 96-well microtitre polystyrene plates were coated previously with 400 ng/well of standard human IgG (Inter-Cell Technologies, Inc., NJ, USA) or human IgM (Chemicon International, CA, USA). Fifty µl of a platelet sample at an appropriate concentration (5–20 × 104 cells/µl) or standard human IgG or human IgM, and 50 µl of 1 : 10 000 diluted horseradish peroxidase conjugated antihuman IgG Fc antibody (goat IgG, F(ab)′2 fraction, ICN Pharmaceuticals., OH, USA) or 1 : 3750 diluted horseradish peroxidase conjugated antihuman IgM Fc antibody (goat IgM, F(ab)′2 fraction, ICN Pharmaceuticals) was added to the wells of flat-bottomed 96-well microtitre polystyrene plates, and then incubated at 37°C for 2 h. Substrate solution (o-phenylenediamine dihydrochloride) was added, followed by a 15-min incubation. After adding 2 N H2SO4, the optical density (OD) at 492 nm was read. PAIgG or PAIgM values were recorded as the IgG or the IgM values per 107 platelet counts (ng/107 platelets).

Anti-dengue virus IgG or IgM activity in the eluted platelet samples

Platelets were separated from plasma samples from 10 patients during the acute phase of a secondary infection (eight patients with DF and two patients with DHF) and six healthy volunteers, who were enrolled at San Lazaro Hospital and St Luke's Medical Center on October, 2001, respectively [16], and antibodies were eluted from the separated platelets as described previously [24]. The eluate was dialysed against phosphate buffered saline (PBS) at 4°C overnight, and concentrated to a final volume of 1 ml containing 3 × 109 platelets by a concentrator. These samples were stored at −80°C until used. The IgG or IgM indirect ELISA for detecting antidengue virus antigens in the eluates of platelet samples was carried out using 96-well flat-bottomed microplates that had been coated previously with 100 µl of a dengue virus antigen mixture (2·5 µg/ml) [16]. The dengue virus antigen mixture consisting of dengue virus types 1, 2, 3 and 4 antigen (each 0·625 µg/ml) was provided by Kurosawa Y (Pentax Co., Ltd, Japan). Dengue type 1 (Hawaii strain), type 2 (ThNH7/93 strain), type 3 (PhNH4/84) and type 4 (CT93-158) viruses were used for antigen preparation. After washing the plate, 50 µl of the undiluted eluates were added to duplicate wells, followed by incubation at room temperature for 30 min. The plate was washed, and then reacted with 100 µl of alkaline phosphatase-conjugated antihuman IgG goat serum (1 : 5000 dilution; Biosource International, Camarillo, CA, USA) or antihuman IgM goat serum (1 : 2500 dilution, Biosource International). Finally, the OD at 405 nm was then measured.

Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as the mean ±s.d. Platelet counts, PAIgG and PAIgM levels during the period between the acute and convalescent phase were tested by the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. The levels of PAIgG, PAIgM and the platelet count between healthy volunteers and patients with dengue virus infections and between patients with DF and DHF were analysed by the Mann–Whitney U-test. A multivariate logistic regression was used to assess the association of PAIgG, PAIgM and the platelet count on the severity of the disease. The significance of the correlations was estimated using Spearman's rank correlation. P < 0·05 was considered to be significant. Statistical software, spss version 10·0 (SPSS Inc., IL, USA) was used for the data analysis.

RESULTS

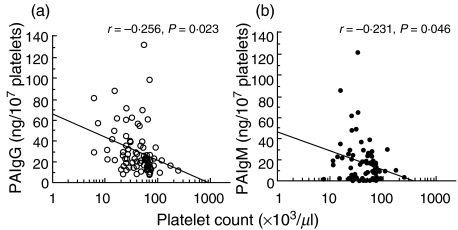

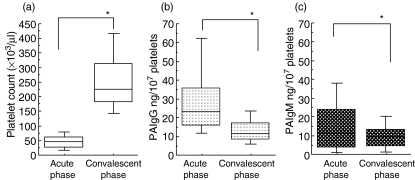

Of the 78 patients with secondary dengue virus infections, 40 and 38, respectively, were diagnosed as DF and DHF. Thirty-eight patients with DHF were classified further into DHF I (n = 9) and DHF II (n = 29). These patients with DHF were therefore free of shock. A significant difference was found in platelet count, PAIgG and PAIgM levels (P < 0·001) between patients in the acute phase of a secondary infection and age-matched healthy volunteers (Table 1). A significant difference in the maximum percentage of haematocrit increase (P < 0·001), PAIgG level (P < 0·01) and PAIgM level (P < 0·001) was found between patients with DF and DHF, while no significant difference was found in age, days after onset and platelet count between these two groups. A weak but a significant correlation was found between the platelet count and the level of PAIgG among the total 78 patients with a secondary dengue virus infection at the time of enrolment, consistent with our findings (r = −0·256, P = 0·023, Fig. 1a) [16]. A weak correlation was also found between the platelet count and PAIgM levels among these patients at the time of enrolment (r = −0·231, P = 0·046; Fig. 1b). The changes in platelet counts and PAIgG or PAIgM were compared in 78 patients with a secondary infection in the period between the acute and convalescent phases. The low baseline platelet counts during the acute phase (47·9 ± 34·6 × 103/µl) increased significantly and recovered to a normal range during the convalescent phase (259·5 ± 112·7 × 103/µl; P < 0·001, Fig. 2a) in these patients. In contrast, the increased baseline PAIgG (30·9 ± 23·1 ng/107 platelet) or PAIgM levels (17·5 ± 20·4 ng/107 platelet) during the acute phase decreased significantly, and returned to a normal level (13·3 ± 7·7 ng/107 platelet for PAIgG, 9·7 ± 7·6 ng/107 platelet for PAIgM) during the convalescent phase in the same subjects (P < 0·001 for PAIgG, Fig. 2b; P < 0·001 for PAIgM, Fig. 2c).

Table 1.

Laboratory data on patients with acute phase of secondary dengue virus infection and healthy volunteers

| Diagnosis (n) | Age (years) | Days after onset | % increase in haematocrit | Platelet count, ×103/µl | PAIgG, ng/107 platelets | PAIgM, ng/107 platelets |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HV (43) | 17·3 | – | – | 273·0 (53·4) | 6·4 (4·2) | 4·2 (3·8) |

| DV infection (78) | 18·2 (5·9) | 5·9 (1·0) | 19·6 (9·8) | 47·9 (34·6)* | 30·9 (23·1)* | 17·5 (20·4)* |

| DF (40) | 17·6 (5·3) | 6·1 (1·1) | 12·4 (6·2) | 51·1 (37·2) | 25·0 (18·4) | 10·3 (11·9) |

| DHF (38) | 18·9 (6·4) | 5·7 (0·9) | 27·3 (6·6)** | 44·7 (31·8) | 37·1 (26·0)*** | 24·8 (24·5)**** |

HV: healthy volunteer; DF: dengue fever; DHF: dengue haemorrhagic fever. Data represent the mean (s.d.).

P < 0·001 (versus HV);

P < 0·001 (versus DF);

P < 0·01 (versus DF);

P < 0·001 (versus DF).

Fig. 1.

Relationship between peripheral platelet count and PAIgG (a, n = 78: open circles) or PAIgM (b, n = 75: closed circles) levels in patients in the acute phase of a secondary dengue virus infection.

Fig. 2.

Comparisons of peripheral platelet count (a, n = 78), PAIgG (b, n = 78) and PAIgM (c, n = 75) levels between the acute (the first test) and convalescent phase (4 days after the first test) of secondary dengue virus infections. *P < 0·001.

The levels of antidengue virus IgG or IgM were determined in eluates of the platelet samples. The OD at 405 nm for the antidengue virus IgG and IgM in eluates from six healthy volunteers were 0·20 ± 0·10 and 0·09 ± 0·05, respectively. In contrast, an increased activity of antidengue virus IgG or IgM was found in eluates from patients in the acute phase of a secondary infection (OD at 405 nm; 1·54 ± 0·35 for antidengue virus IgG, 0·35 ± 0·20 for antidengue virus IgM).

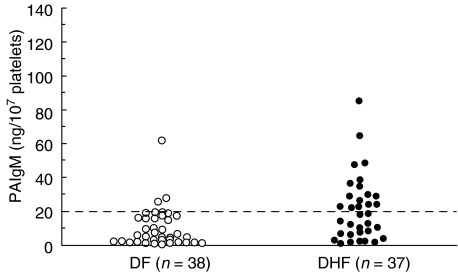

We next examined whether the level of PAIgG or PAIgM correlated directly with the haematocrit increase, which is a critical indicator of vascular permeability, in patients in the acute phase of a secondary infection. No significant correlation was found between the level of PAIgG and the percentage increase in haematocrit (n = 78, r = 0·057, P > 0·05). Although a weak correlation was found between the level of PAIgM and the percentage increase in haematocrit (n = 75, r = 0·23, P = 0·045), no significant correlation was found between these two parameters in patients with DF (n = 38, r = −0·13, P > 0·05) and in patients with DHF (n = 37, r = −0·31, P > 0·05). A logistic regression, however, demonstrated that the PAIgM was associated independently with DHF among the parameters of PAIgG, PAIgM and platelet count (P < 0·01). A level of PAIgM higher than 20 ng/107 platelets during the acute phase of a secondary infection was a predictor of the subsequent development of DHF with a sensitivity of 48·6% (18/37) and a specificity of 92·1% (35/38) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Comparison of the levels of PAIgM between patients with DF (n = 38; open circles) and DHF (n = 37; closed circles) during the acute phase of a secondary dengue virus infection. The horizontal broken line represents the cut-off value (20 ng/107 platelets) for the prediction of DHF.

DISCUSSION

In this paper, we have demonstrated that the levels of PAIgM as well as PAIgG are correlated significantly with platelet count in the acute phase of secondary dengue virus infections. PAIgG and PAIgM levels were both significantly higher in the acute phase than in the convalescent phase. The changes in PAIgM levels were found to be similar to the levels of PAIgG during the acute and convalescent phases. We also found an increased activity of antidengue virus IgM as well as antidengue virus IgG in eluates from patients in the acute phase of a secondary infection, although the antidengue virus IgM activities were relatively lower than that of antidengue virus IgG in the eluate samples. These data suggest that PAIgM formation involving antidengue virus IgM may also contribute to the induction of thrombocytopenia in patients in the acute phase of a secondary infection. As we have previously suggested a possible explanation for thrombocytopenia by the transient formation of PAIgG [16], PAIgM formation may also contribute to the induction of thrombocytopenia during the acute phase of secondary infection. While PAIgG formation may induce thrombocytopenia through both Fc receptor- and complement receptor-mediated platelet clearance by macrophage and/or complement-mediated platelet lysis [9,25], PAIgM formation may also result in thrombocytopenia by the same mechanisms except via the use of Fc receptors, based on the function of the IgM pentamer.

A previous in vitro study reported that dengue-2 virus binds to platelets in the presence of a virus-specific antibody [17]. In our preliminary study of dengue virus RNA detection by RT-PCR among 21 patients with a secondary infection, a high positive rate (42·8%) was found in the purified platelet samples (data not shown). These data suggest that the dengue virus is located on the circulating platelets, and support our hypothesis of a mechanism of thrombocytopenia involving the formation of PAIgG and PAIgM in patients with secondary infections. However, we cannot rule out that the dengue virus other than type 2 forms the immune complex with virus-specific IgG antibody, which subsequently binds to platelet via the Fc receptor. While a significant increase in the levels of PAIgG or PAIgM and a weak but significant correlation between platelet count and the level of PAIgG or PAIgM was found in patients with the acute phase of secondary infection, the levels of PAIgG in 15 patients (19·2%) and the levels of PAIgM in 38 patients (50·7%) remained within the normal range (0–14·8 ng/107 platelets for PAIgG, 0–11·8 ng/107 platelets for PAIgM). These data indicate that mechanisms involved in the development of thrombocytopenia other than PAIgG or PAIgM may also be operative in these patients. In addition, the contribution of PAIgG to the induction of thrombocytopenia appears to be much greater than that of PAIgM.

As predictors of DHF, previous studies have proposed certain host factors such as soluble tumour necrosis factor receptors and soluble vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 and dengue virus non-structural protein NS1 [26–28]. An increased level of PAIgM during the acute phase of a secondary infection was highly specific for the development of DHF (92·1%) in this study, although its sensitivity was relatively low (48·6%). PAIgM, therefore, would be a specific predictor of DHF in cases accompanied by a virological diagnosis. Interpretation of our data, however, is limited, because the study subjects involved cases of DF and DHF with no shock in this study. More importantly, it is possible that the formation of PAIgM could be linked to the increased vascular permeability, which is characteristic of DHF. A recent in vitro study has reported on the adhesion of platelets to dengue virus-infected endothelial cells [29]. Activated platelets associated with dengue virus and antidengue virus IgM as well as dengue virus-infected endothelial cells may be involved in the mechanism of the increased vascular permeability associated with DHF [30,31].

In summary, we have demonstrated that the increased levels of PAIgG and PAIgM, involving antidengue virus IgG and IgM, were associated closely with thrombocytopenia during the acute phase of secondary dengue virus infections. An increased level of PAIgM during the acute phase of secondary infection was associated independently with the development of DHF, and highly specific for DHF. The formation of platelet-associated immunoglobulins may play a critical role in the mechanisms of thrombocytopenia and the accompanying increased vascular permeability. Further elucidation of the involvement of platelet-associated immunoglobulins on the mechanisms of thrombocytopenia and the increased vascular permeability is required.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Arturo B. Cabanban MD and the staff in Pavilion 1, San Lazaro Hospital and the Research and Biotechnology Division, St Luke's Medical Center. This study was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B: 14406019) from the Ministry of Education, Science and Culture, Japan and a grant from St Luke's Medical Center (01–018).

REFERENCES

- 1.Igarashi A. Impact of dengue virus infection and its control. FEMS Immunol Med M/C. 1997;18:291–300. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1997.tb01058.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guzman MG, Kouri G. Dengue: an update. Lancet Infect Dis. 2002;2:33–42. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(01)00171-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Srichaikul T, Nimmannitya S. Haematology in dengue and dengue haemorrhagic fever. Bailliere's Clin Haematol. 2000;13:261–76. doi: 10.1053/beha.2000.0073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burke DS, Nisalak A, Jhonson DE, Scott RM. A prospective study of dengue infections in Bangkok. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1988;38:172–80. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1988.38.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Halstead SB. Pathogenesis of dengue: challenges of molecular biology. Science. 1988;239:476–81. doi: 10.1126/science.3277268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guzman MG, Kouri GP, Bravo J, Soler M, Vazquez S, Morier L. Dengue hemorrhagic fever in Cuba, 1981: a retrospective seroepidemiologic study. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1990;42:179–84. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1990.42.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.La Russa VF, Innis BL. Mechanism of dengue virus-induced bone marrow suppression. Bailliere's Clin Haematol. 1995;8:249–70. doi: 10.1016/s0950-3536(05)80240-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mitrakul C, Poshyachinda M, Futralul P, Sangkawibha N, Ahandrik S. Hemostatic and platelet kinetic studies in dengue hemorrhagic fever. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1977;26:975–84. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1977.26.975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boonpucknavig S, Vuttiviroj O, Bunnag C, Bhamarapravati N, Nimmanitya S. Demonstration of dengue antibody complexes on the surface of platelets from patients with dengue hemorrhagic fever. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1979;28:881–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McMillian R. Chronic idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. N Engl J Med. 1981;304:1135–47. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198105073041904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cines DB, Blanchette VS, Chir B. Immune thrombocytopenic purpura. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:995–1008. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra010501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Muller-Eckhardt C, Kayser W, Mersch-Baumert K, et al. The clinical significance of platelet-associated IgG: a study on 298 patients with various disorders. Br J Haematol. 1980;46:123–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1980.tb05942.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rand ML, Wright JF. Virus-associated idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. Transfus Sci. 1998;19:253–9. doi: 10.1016/s0955-3886(98)00039-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kitamura K, Ohta H, Ihara T, et al. Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura after human herpesvirus 6 infection. Lancet. 1994;344:830. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)92390-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Toyoshige M, Takahashi H. Increase of platelet-associated IgG (PA-IgG) and hemophagocytosis of neutrophils and platelets in parvovirus B19 infection. Int J Hematol. 1998;67:205–6. doi: 10.1016/s0925-5710(98)00008-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oishi K, Inoue S, Cinco MTDD, et al. Correlation between increased platelet-associated IgG and thrombocytopenia in secondary dengue virus infections. J Med Virol. 2003;71:259–64. doi: 10.1002/jmv.10478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang S, He R, Patarapotikul J, Innis BL, Anderson R. Antibody-enhanced binding of dengue-2 virus to human platelet. Virology. 1995;213:254–7. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Innis BL, Nisalak A, Nimmannitya S, et al. An enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay to characterize dengue infections where dengue and Japanese encephalitis co-circulate. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1989;40:418–27. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1989.40.418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bundo K, Igarashi A. Antibody-captured ELISA for detection of immunoglobulin M antibodies in sera from Japanese encephalitis and dengue hemorrhagic fever patients. J Virol Meth. 1985;11:15–22. doi: 10.1016/0166-0934(85)90120-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morita K, Tanaka M, Igarashi A. Rapid identification of dengue virus serotypes by using polymerase chain reaction. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:2107–10. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.10.2107-2110.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.World Health Organization (WHO). Dengue haemorrhagic fever: diagnosis, treatment, prevention and control. 2. Geneva: WHO; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Libraty DH, Endy TP, Houng HH, et al. Differing influences of virus burden and immune activation on disease severity in secondary dengue-3 virus infection. J Infect Dis. 2002;185:1213–21. doi: 10.1086/340365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clarke DH, Casals J. Techniques for hemagglutination and hemagglutination-inhibition with arthropod-borne viruses. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1958;7:561–73. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1958.7.561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Helmerhorst FM, van Oss CJ, Bruynes ECE, von Engelfriet CP, dem Borne AEGKr. Elution of granulocyte and platelet antibodies. Vox Sang. 1982;43:196–204. doi: 10.1111/j.1423-0410.1982.tb00012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bokisch VA, Top FH, Jr, Russell PK, Dixon FJ, Muller-Eberhard HJ. The potential pathogenic role of complement in dengue hemorrhagic shock syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1973;289:996–1000. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197311082891902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Green S, Vaughn DW, Kalayanarooj S, et al. Early immune activation in acute dengue illness is related to development of plasma leakage and disease severity. 1999;179:755–62. doi: 10.1086/314680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Murgue B, Cassar O, Deparis X. Plasma concentrations of sVCAM-1 and severity of dengue infections. J Med Virol. 2001;65:97–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Libraty DH, Young PR, Pickering D, et al. High circulating levels of the dengue virus nonstructural protein NS1 early in dengue illness correlate with development of dengue hemorrhagic fever. J Infect Dis. 2002;186:1165–8. doi: 10.1086/343813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krishnamurti C, Peat RA, Cutting MA, Rothwell SW. Platelet adhesion to dengue-2 virus-infected endothelial cells. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2002;66:435–41. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2002.66.435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Krishnamurti C, Kalayanarooj S, Cutting MA, et al. Mechanisms of hemorrhage in dengue without circulatory collapse. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2001;65:840–7. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2001.65.840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Avirutnan P, Malasit P, Seliger B, Bhakdi S, Husmann M. Dengue virus infection of human endothelial cells leads to chemokine production, complement activation, and apoptosis. J Immunol. 1998;161:6338–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]