Abstract

FREQUENCY (FRQ), a key component of the Neurospora circadian clock, is progressively phosphorylated after its synthesis. Previously, we identified casein kinase II (CKII) as a kinase that phosphorylates FRQ. Disruption of the catalytic subunit of CKII abolishes the clock function; it also causes severe defects in growth and development. To further establish the role of CKII in clock function, one of the CKII regulatory subunit genes, ckb1, was disrupted in Neurospora. In the ckb1 mutant strain, FRQ proteins are hypophosphorylated and more stable than in the wild-type strain, and circadian rhythms of conidiation and FRQ protein oscillation were observed to have long periods but low amplitudes. These data suggest that phosphorylation of FRQ by CKII regulates FRQ stability and the function of the circadian feedback loop. In addition, mutations of several putative CKII phosphorylation sites of FRQ led to hypophosphorylation of FRQ and long-period rhythms. Both CKA and CKB1 proteins are found in the cytoplasm and in the nucleus, but their expressions and localization are not controlled by the clock. Finally, disruption of a Neurospora casein kinase I (CKI) gene, ck-1b, showed that it is not required for clock function despite its important role in growth and developmental processes. Together, these data indicate that CKII is an important component of the Neurospora circadian clock.

Circadian clocks control a wide variety of physiological and molecular activities in almost all organisms. Circadian clocks are made of autoregulatory feedback loops, in which there are positive and negative elements (16, 53). In Neurospora, FREQUENCY (FRQ), WHITE COLLAR-1 (WC-1), and WC-2 proteins are essential components of the frq-wc-based circadian feedback loops (35). In constant darkness, WC-1 and WC-2, the two transcription factors containing the PER-ARNT-SIM domains, form a heterodimer through their PAS domains, bind to the promoter of frq, and activate its transcription (7, 9, 10, 12, 19). On the other hand, the homodimeric FRQ proteins feed back to repress the transcription of frq by interacting with the WC-1/WC-2 complex, forming the negative feedback loop (2, 8, 15, 20, 32, 40). In addition, FRQ positively regulates the levels of both WC-1 and WC-2 proteins, forming positive feedback loops that are important for the robustness and stability of the clock (7, 9, 29, 40). Besides their essential roles in circadian feedback loops, WC-1 and WC-2 are also essential components in the light input pathway of the clock, and WC-1 is the circadian blue light photoreceptor (11, 12, 19, 22, 28, 31).

Phosphorylation of clock proteins is one of the most important posttranscriptional mechanisms in the regulation of circadian clocks (17, 18, 20, 23, 24, 27, 30, 33, 36, 38, 42, 46, 49, 50). In Neurospora, FRQ, WC-1, and WC-2 proteins are phosphorylated in vivo (20, 44, 48). FRQ, the negative element in the circadian negative feedback loop, is immediately phosphorylated after its synthesis and becomes extensively phosphorylated prior to its disappearance (20). Previously, using biochemical purification, we identified two kinases, a calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase and the Neurospora casein kinase II (CKII), as the kinases that phosphorylate FRQ (51, 52). In a Neurospora mutant strain in which the catalytic subunit gene of CKII (cka) is disrupted, FRQ levels are high and FRQ proteins are hypophosphorylated (51). Moreover, the circadian rhythms of frq RNA, FRQ protein, and clock-controlled genes are abolished in this mutant, suggesting that the phosphorylation of FRQ by CKII is essential for clock function. Furthermore, our results suggest that the phosphorylation of FRQ by CKII may have at least three functions: regulating the stability of FRQ, regulating the interactions between FRQ and the WC proteins, and an important role in the closing of the Neurospora circadian negative feedback loop. A Neurospora casein kinase I (CK1a) was also implicated as a FRQ kinase; the CK-1a protein interacts with FRQ in vivo and phosphorylates FRQ in vitro (21). Although both CKI and CKII are Ser/Thr protein kinases, they are significantly different in their structures and substrate specificities. Apparently, therefore, several kinases work together to phosphorylate FRQ and regulate its function.

Eukaryotic CKII holoenzyme is an α2β2 heterotetramer, and most eukaryotic organisms have at least two distinct catalytic α subunits and two different regulatory β subunits (41). While the α subunits are required for CKII kinase activity and for survival in most organisms (except for Neurospora), the β subunits regulate the kinase activity and substrate specificity of the α subunits, and they are not required for cell survival (6, 43). In Neurospora, there is only one CKII catalytic subunit gene (cka), but there are two different CKII regulatory subunit genes, named ckb1 and ckb2 (51). Even though disruption of cka (resulting in complete elimination of CKII activity) is not lethal for Neurospora, the cka mutant has severe defects in growth and development. Therefore, it is likely that these defects might contribute to the clock phenotype we observed at the molecular level. In this study, to further establish the role of CKII in regulating clock function, one of the CKII regulatory subunit genes, ckb1, was disrupted in Neurospora. On race tubes, the ckb1 mutant strains exhibit long-period and low-amplitude conidiation rhythms and become arrhythmic afterwards. In the ckb1 mutant, FRQ proteins are hypophosphorylated and more stable than in the wild-type strain and oscillate with a low amplitude in constant darkness (DD). Consistent with CKII phosphorylating FRQ in vivo, several CKII phosphorylation consensus sites of FRQ were shown to be phosphorylated in vivo, and their mutations resulted in long-period rhythms. Both CKA and CKB1 proteins are found in the cytoplasm and nucleus, but their expression and localization are not controlled by the clock. Finally, disruption of a Neurospora CKI gene (ck-1b) showed that although it is important for normal growth and developmental processes, it is not required for the function of the clock. Together, these data indicate the important roles of CKII in the Neurospora circadian clock.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains, culture conditions, and race tube assay.

The bd a (wild-type clock) strain was the wild-type strain used in this study. 301-6 (bd his-3 A) or 303-10 (bd frq10 his-3) was the host strain for the his-3 targeting constructs. Culture conditions were the same as described previously (2, 14). Medium for race tube assays contained 1× Vogel's, 2% glucose, 50 ng of biotin/ml, and 1.5% agar.

Plasmid constructs and Neurospora transformation.

pKAJ120 (containing the entire frq gene and a his-3 targeting sequence) is the parental plasmid for all frq mutagenesis constructs described in this study (3). All the point mutations of the FRQ open-reading frame (ORF) were constructed using the Transformer site-directed mutagenesis kit (Clontech Laboratories, Inc.), and pUC19Mfrq was used as the in vitro mutagenic template (33). After mutagenesis, the region containing the mutation was subcloned into pKAJ120. All constructs were confirmed by DNA sequencing and were targeted to the his-3 locus of a frq null strain (303-10) (3) by transformation as previously described (4).

Disruption of ckb1 and ck-1b genes in Neurospora by repeat-induced point mutation (RIP).

The PCR fragment containing the entire ckb1 or ck-1b ORF was cloned into pDE3dBH and introduced into the his-3 locus of a wild-type strain (301-6 [bd his-3 A]) by transformation. Southern blot analysis was performed to identify transformants that carried an additional copy of the gene, and a positive transformant was crossed with a wild-type strain (bd a). Sexual spores of the cross were picked up individually and germinated on slants containing histidine. DNA sequencing and Western blot analyses were performed to identify strains in which the ckb1 or ck-1b gene was disrupted.

Generation of antisera against CKA and CKB1.

GST-CKA (containing the entire cka ORF) and GST-CKB1 (amino acids [aa] 96 to 336) fusion proteins were expressed in Escherichia coli BL21 cells, and the inclusion bodies containing the recombinant proteins were purified as previously described (8). Antisera were generated by immunizing New Zealand White rabbits with the purified recombinant proteins according to standard protocols (Cocalico Biologicals, Inc.) and were used in Western blot analysis without further purification.

Protein and RNA analyses.

Protein extraction, nuclei preparation, quantification, and Western blot analysis were performed as described elsewhere (8, 20, 37). RNA extraction and Northern blot analysis were performed as described previously (2, 13). Equal amounts of total RNA (20 μg) were loaded onto agarose gels for electrophoresis. The gels were blotted and probed with an RNA probe specific for frq, ccg-1, or ccg-2.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Disruption of ckb-1 resulted in circadian rhythms of long period and low amplitude.

Previously, we biochemically purified the CKII holoenzyme as a kinase that phosphorylates FRQ, a central component of the circadian clock in Neurospora (51). Protein sequencing of the purified CKII revealed that it contains one catalytic subunit (CKA) and two different regulatory subunits (CKB1 and CKB2), consistent with the prediction from the nearly complete Neurospora genome sequence. Disruption of the cka gene confirmed that CKA is the only α subunit and is required for CKII activity in Neurospora. Although cka is not essential for cell survival in Neurospora, its disruption resulted in severe growth and developmental defects along with its circadian clock phenotypes. It is possible, therefore, that the clock phenotypes observed for the cka mutant were a result of its growth and developmental defects. To address this concern, we disrupted one of the regulatory subunits (ckb1) in Neurospora by RIP (see Materials and Methods) (45). Because there are two regulatory subunit genes in Neurospora, we expected that disruption of one of the genes would not cause severe growth and developmental defects. The clock defects associated with ckb1 disruption, therefore, can be separated from other defects. In addition, if FRQ phosphorylation by CKII regulates not only FRQ stability but also the normal function of the circadian feedback loop, as we proposed previously (51), we would predict that in the absence of CKB1, the period of the clock would be long and the quality of the rhythms would be poor.

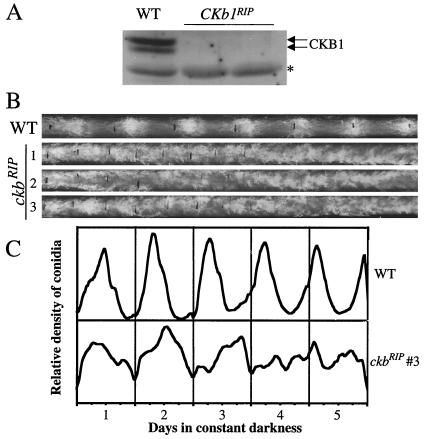

Analysis of the RIP progenies by Western blot analysis using antiserum specific for Neurospora CKB1 identified several strains (ckb1RIP) in which expression of CKB1 was eliminated (Fig. 1A). DNA sequencing of the endogenous ckb1 genes in these strains revealed premature stop codons created by RIP in the gene (data not shown). In one of the strains, a G-A mutation created a premature stop codon at aa 9 of CKB1, and this strain was used for the molecular studies described here.

FIG. 1.

Disruption of the ckb1 gene in Neurospora resulting in circadian conidiation rhythms of low amplitude and long period. (A) Western blot analysis showing that expression of CKB1 protein was abolished in two independent ckb1RIP strains. The asterisk designates a nonspecific band recognized by our CKB1 antiserum. (B) Race tube assay showing the conidiation rhythms in DD. Black lines indicate the growth front every 24 h. Severe independent ckb1RIP strains were examined by multiple sets of race tubes, and the representative race tube results are shown. (C) Densitometric analysis of the results of the race tube assay shown in panel B.

On slants, the ckb1RIP strains, unlike the ckaRIP strains, which grow very slowly and produce few conidia, resembled the wild-type strain, although with slightly fewer aerial hyphae. To examine the growth rates and circadian conidiation rhythms of the mutants, race tube assays were performed in DD. On race tubes, the growth rates of the ckb1RIP strains were about half that of the wild-type strain (Fig. 1B). In contrast, the growth rates of the ckaRIP strains are less than 10% that of the wild type. These phenotypes of the ckb1RIP mutants indicated that although the disruption of the ckb-1 gene affected normal growth of Neurospora to some extent, there were no severe growth or developmental defects. Growth defects were found in many Neurospora mutants (some more severe than those of the ckb1RIP mutants) in which normal circadian conidiation rhythms were observed (26, 51). For the ckb1RIP mutants, arrhythmic conidiation was seen in most of the race tubes (Fig. 1B). In some race tubes, however, in the initial 2 to 3 days in DD, long-period (∼28 h) circadian conidiation rhythms could be observed, but the rhythms had low amplitudes and became arrhythmic after 3 to 4 days (Fig. 1B and C). These data indicate that in the ckb1RIP mutants, as expected, circadian conidiation rhythms were severely affected.

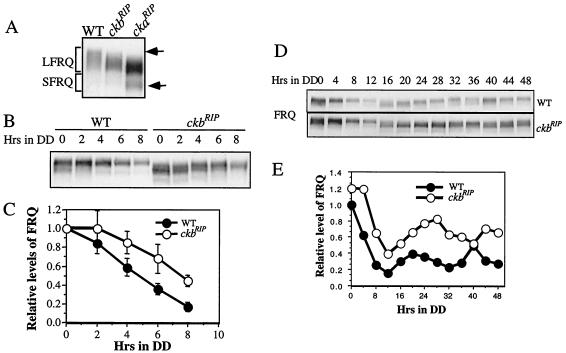

Consistent with CKII being a kinase that phosphorylates FRQ in vivo and with the reduction but not complete elimination of CKII kinase activity in the ckb1RIP strain, an FRQ level and an FRQ phosphorylation pattern intermediate between those of the wild-type and the ckaRIP strains were seen in the ckb1RIP strain (Fig. 2A and B). In this strain, most of the FRQ proteins are hypophosphorylated, and the level of FRQ is higher than that of the wild type. In addition, the FRQ protein was more stable after a light/dark (LD) transition in the ckb1RIP strain than in the wild type (Fig. 2B and C). These data are in agreement with our previous conclusion that phosphorylation of FRQ by CKII affects its stability.

FIG. 2.

FRQ expression in the ckb1RIP strain. (A) Western blot analysis showing FRQ phosphorylation patterns in the wild-type, ckb1RIP, and ckaRIP strains. Cultures were harvested in LL. Arrows indicate the hyperphosphorylated or hypophosphorylated FRQ species. (B) Western blot analysis showing FRQ degradation in the wild-type and ckb1RI strains after an LD transition. (C) Densitometric analysis of the results from three independent experiments. Error bars are standard deviations. (D) Rhythmic expression of FRQ in the wild-type and ckb1RI strains in DD. The experiment was repeated multiple times, and similar results were obtained. (E) Densitometric analysis of the results shown in panel D.

In the ckaRIP mutant, there is no circadian oscillation of FRQ proteins, and the level of FRQ protein is constantly high in the dark (51). To determine whether the poor conidiation rhythms of the ckb1RIP strain were due to the low-amplitude FRQ oscillation, Western blot analysis was performed to examine the oscillation of FRQ in constant darkness in the mutant. As seen in Fig. 2D and E, after the initial LD transition, the amplitude of FRQ oscillation in DD was low in the mutant, and levels of FRQ were significantly higher in the ckb1RIP strain than in the wild type. In addition, the peak and trough of FRQ oscillation were significantly delayed in the mutant, indicating a long-period rhythm. In contrast to the dramatic oscillation of the FRQ phosphorylation states seen in the wild-type strain, only slight changes in phosphorylation profile could be seen in the mutant after DD16 (comparing DD36 to DD40).

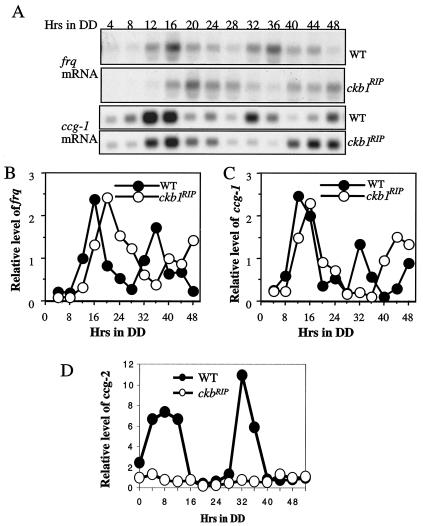

In several Neurospora mutant strains in which the FRQ protein was more stable than that in the wild-type strain, conidiation and FRQ protein rhythms had long periods (>28 h), but these rhythms also were robust (21, 33). Even though the slow degradation rate of FRQ in the ckb1RIP strain is consistent with the long-period rhythms seen, the low-amplitude and arrhythmic conidiation rhythms and the low-amplitude FRQ protein oscillation suggest that additional aspects of the clock function were affected in the ckb1RIP strains. Previously, we showed that the level of frq mRNA was high and arrhythmic in the ckaRIP strain, suggesting that the negative feedback loop is impaired without the CKII kinase activity. In the ckb1RIP strain, the period of frq mRNA oscillation was long, and the levels of frq were comparable to those in the wild-type strain (Fig. 3A and B) despite its significantly higher FRQ levels (Fig. 2D and E). In contrast to the ckaRIP strain, which lacks any CKII kinase activity, the CKII catalytic subunit and another regulatory subunit were still functional in the ckb1RIP strain. These data suggest that the negative feedback loop was still functional in the ckb1RIP mutant due to its remaining CKII activity. However, the reduction of CKII activity and the hypophosphorylated FRQ protein in the ckb1RIP strain may partially impair the function of the circadian negative feedback loop, resulting in the low-amplitude FRQ oscillation and conidiation rhythms.

FIG. 3.

Rhythmic expression of frq, ccg-1, and ccg-2 in the ckb1RIP strain. (A) Rhythmic expression of frq and ccg-1 in the wild-type and ckb1RI strains in DD. The experiments were repeated multiple times, and similar results were obtained. (B and C) Densitometric analysis of the results shown in panel A. (D) Expression of ccg-2 in the wild-type and ckb1RI strains in DD.

The rhythmic expressions of two clock-controlled genes, ccg-1 and ccg-2 (5, 34), were also examined in the ckb1RIP strain. Like frq, ccg-1 was rhythmically expressed with a long period in the mutant (Fig. 3A and C). In contrast, levels of ccg-2 were low and arrhythmic in the ckb1RIP strain (Fig. 3D), similar to its expression in the ckaRIP strain (51). Thus, the clock control of these two ccg's is differentially regulated in the ckb1RIP strain. It is possible that the hypophosphorylated FRQ in the ckb1RIP mutant failed to exert clock control over the expression of ccg-2, while its control of ccg-1 expression was not severely affected.

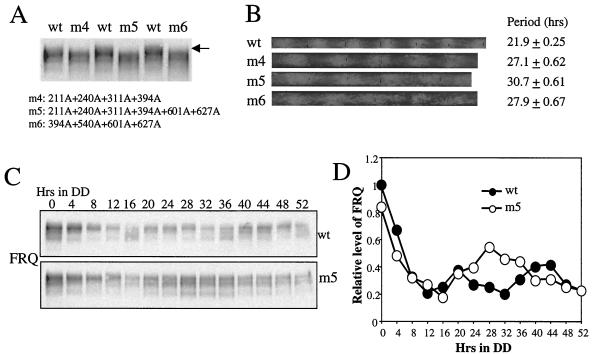

Mutation of putative CKII phosphorylation sites in FRQ resulting in the disappearance of some phosphorylated FRQ species and long-period circadian rhythms.

Although the FRQ region containing the previously identified three FRQ phosphorylation sites can be phosphorylated by CKII in vitro (33, 51), these sites do not resemble the typical CKII consensus phosphorylation sites, (S/T)XX(D/E/Tp/Sp) (p stands for a phosphorylated residue at the +3 position) (39, 41). Therefore, CKII may phosphorylate other sites on FRQ. There are 29 sites on FRQ that match the (S/T)XX(D/E) motif, but more putative CKII sites can be identified if the +3 position can be a phosphorylated amino acid (for example, the first PEST domain of FRQ) (21). To demonstrate that the putative CKII sites on FRQ are phosphorylated in vivo, six potential CKII sites (S211, S240, T311, S394, S601, and S627) were mutated to alanine residues. frq constructs with four (m4 and m6) or all six (m5) of these sites mutated were transformed into a frq null strain (3). As shown in Fig. 4A, mutation of these putative CKII sites resulted in disappearance of the hyperphosphorylated FRQ species, indicating that some of these sites are indeed phosphorylated in vivo. As indicated by the various phosphorylated FRQ forms in the mutants, however, there are other unknown phosphorylation sites. In addition, transformants with mutant FRQ exhibited long-period (27 or 30 h) circadian conidiation and FRQ protein rhythms (Fig. 4B to D). These data suggest that phosphorylation of these sites regulates the stability of FRQ and period length of the clock.

FIG. 4.

Mutations of putative CKII phosphorylation sites of FRQ resulting in the disappearance of phosphorylated FRQ species and long-period circadian rhythms. (A) FRQ phosphorylation patterns in frq mutant strains. The arrow indicates the hyperphosphorylated FRQ species in the wild-type strain. Mutations of FRQ in the mutant strains are indicated below. (B) Race tube assays showing the long-period conidiation rhythms in the mutant. The periods ([plusmn] standard deviation) of the mutants are indicated. (C) Rhythmic expression of FRQ in the wild-type and m5 strains in DD. (D) Densitometric analysis of the results shown in panel C.

Constitutive expression of CKA and CKB1 in the cytoplasm and in the nucleus.

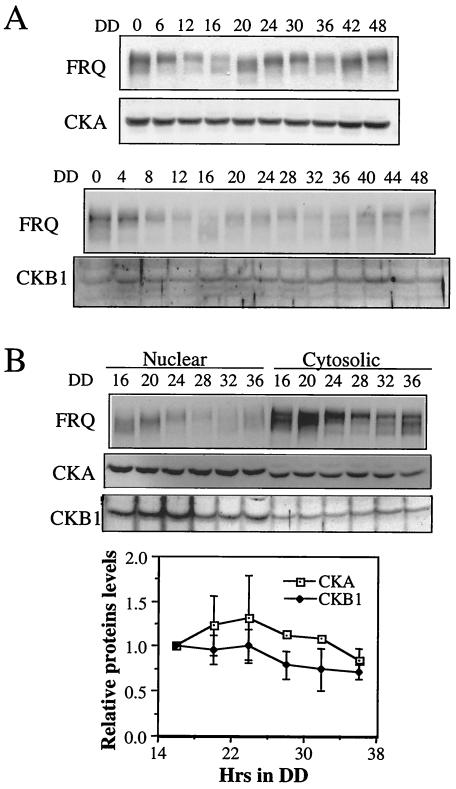

The dramatic oscillation of FRQ phosphorylation states raises the possibility that FRQ kinase activity is also rhythmic. Previously, we showed that the level of cka mRNA was constant in constant darkness (51), but it is possible that the protein level and localization of the CKII subunits are under circadian control, as demonstrated for CKI in Drosophila and mice (25, 27). As shown in Fig. 5A, the levels of CKA and CKB1 appeared to be constant in constant darkness for 2 days despite the robust oscillations of FRQ levels and phosphorylation states in the same cells. To examine whether the cellular localizations of CKA and CKB1 are under clock control, nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts were prepared for samples harvested at different times of the day in constant darkness. Because FRQ is found in the cytoplasm and in the nucleus, we should expect the CKII subunits in these locations. As expected, CKA and CKB1 were found in the cytoplasm and in the nucleus, but their levels appeared to be constant at different times of the day (Fig. 5B). Furthermore, CKII kinase activity did not cycle in DD (data not shown). Together, these data suggest that oscillation of FRQ phosphorylation profiles is not due to the cycling of CKII activity and is probably caused by the rhythmic oscillation of FRQ levels.

FIG. 5.

Expression and cellular localization of CKA and CKB1 proteins. (A) Western blot analysis showing the expression of CKA and CKB1 in the wild-type strain in DD. Representative results from three independent experiments are shown. The slightly high levels of CKB at DD4 and DD16 were not consistently seen in other experiments. (B) (Top) Western blot analysis showing levels of CKA and CKB1 in the cytoplasm and in the nucleus in DD at different time points. (Bottom) Densitometric analysis of the results from three independent experiments showing the levels of CKA and CKB in the nucleus. Error bars are standard deviations.

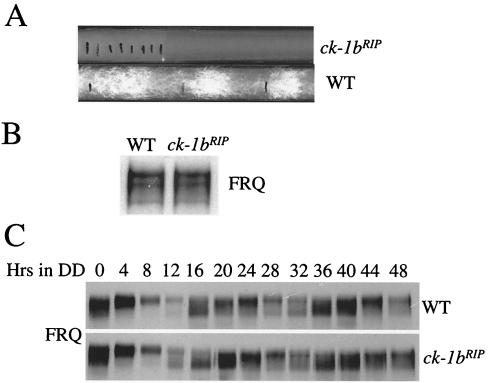

ck-1b is not required for clock function despite its important role in growth and development.

Gorl et al. previously showed that there are two CKI homologs (CK-1a and CK-1b) in Neurospora and that both kinases can phosphorylate FRQ in vitro (21). Unlike CKII, CKI functions as a monomer. Although CK-1a interacts with FRQ in vivo, the in vivo role of CK-1b in FRQ phosphorylation and in the circadian clock is unclear. To study the function of CK-1b, we made ck-1b null Neurospora strains by RIP. Sequencing of endogenous ck-1b genes in the RIP mutants showed that in several strains, premature stop codons of ck-1b were created by RIP (see Materials and Methods). In one strain, in addition to many point mutations in the ck-1b gene, there are two premature stop codons at aa 53 and aa 78 due to C-T mutations. Therefore, this strain should not express any functional CK-1b protein. On slants and in race tube assays, the ck-1bRIP strains showed severe growth and developmental defects, with few aerial hyphae and conidia produced, and their clock function could not be examined by the race tube assay (Fig. 6A). On race tubes, their growth rates were about 10% that of the wild type, similar to growth rates of the ckaRIP strains (51). To compare the FRQ level and its phosphorylation profile in the ck-1bRIP strain to those of the wild-type strain, Western blot analysis was performed for cultures harvested in constant light (LL). As shown in Fig. 6B, comparable FRQ levels and phosphorylation patterns were observed in the two strains. To examine whether the clock was functional in the ck-1bRIP strain, expression of FRQ was examined in DD for 2 days. In contrast to the dramatic changes of FRQ expression in the ckaRIP and ckb1RIP strains (51) (Fig. 2), both the levels of FRQ and its phosphorylation states were rhythmic in the ck-1bRIP strain and very similar to those of the wild-type strain. These data demonstrate that the ck-1b gene is not required for the clock function in Neurospora. The normal function of the clock and the severe growth and developmental defects in the ck-1bRIP strain indicate that there is no direct link between circadian clock and growth and developmental processes in Neurospora.

FIG. 6.

Normal FRQ expression and oscillation in the ck-1bRIP strain despite its severe defects in growth and development. (A) Race tube assay showing the slow growth rate of the ck-1bRIP strain. Black lines mark the growth front every 24 h. (B) Western blot analysis showing the FRQ phosphorylation patterns in the wild-type and ck-1bRIP strains. Cultures were harvested in LL. (C) Rhythmic expression of FRQ in the wild-type and ck-1bRIP strains in DD.

In this study, we have shown that disruption of the regulatory subunit gene of CKII, ckb1, in Neurospora led to hypophosphorylation of FRQ and circadian rhythms of long periods and low amplitudes. Several putative CKII phosphorylation sites of FRQ were shown to be phosphorylated in vivo, and mutation of these sites resulted in long-period circadian rhythms. Although these data suggest that the phosphorylation of FRQ by CKII regulates FRQ stability, the low-amplitude conidiation and FRQ protein rhythms in the ckb1RIP strain are consistent with our previous conclusion that FRQ phosphorylation by CKII is important for the function of the circadian negative feedback loop. Furthermore, we showed that the expressions of CKA and CKB1 proteins are not controlled by the clock. Together, these data firmly established the critical role of CKII in the Neurospora circadian clock.

Recently CKII was also implicated as an important component in the circadian clock of Drosophila (1, 30). Although the Drosophila CKII phosphorylates PERIOD protein in vitro, its mode of action in vivo remains unclear, since the mutated CKII catalytic subunit gene in the homozygous fly is lethal. In Arabidopsis, CKII subunits have been shown to interact and phosphorylate the circadian clock-associated 1 (CCA1) protein in vitro and in yeast two-hybrid assays (46, 47). The phosphorylation of CCA1 by CKII-like activity in vitro affects formation of a DNA-protein complex containing CCA1. Furthermore, overexpression of a regulatory subunit of CKII resulted in shortening of the periods of circadian rhythms in Arabidopsis. Although its role in mammalian circadian clocks remains to be determined, CKII appears to be a common circadian clock element in fungi, plants, and insects, raising the possibility that CKII may be an evolutionary link between different eukaryotic circadian systems.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health to Y. Liu (GM 62591). Y. Liu is the Louise W. Kahn Scholar in Biomedical Research at UT Southwestern Medical Center.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akten, B., E. Jauch, G. K. Genova, E. Y. Kim, I. Edery, T. Raabe, and F. R. Jackson. 2003. A role for CK2 in the Drosophila circadian oscillator. Nat. Neurosci. 6:251-257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aronson, B., K. Johnson, J. J. Loros, and J. C. Dunlap. 1994. Negative feedback defining a circadian clock: autoregulation in the clock gene frequency. Science 263:1578-1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aronson, B. D., K. A. Johnson, and J. C. Dunlap. 1994. The circadian clock locus frequency: a single ORF defines period length and temperature compensation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:7683-7687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bell-Pedersen, D., J. C. Dunlap, and J. J. Loros. 1996. Distinct cis-acting elements mediate clock, light, and developmental regulation of the Neurospora crassa eas (ccg-2) gene. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16:513-521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bell-Pedersen, D., J. C. Dunlap, and J. J. Loros. 1992. The Neurospora circadian clock-controlled gene, ccg-2, is allelic to eas and encodes a fungal hydrophobin required for formation of the conidial rodlet layer. Genes Dev. 6:2382-2394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bidwai, A. P., J. C. Reed, and C. V. Glover. 1995. Cloning and disruption of CKB1, the gene encoding the 38-kDa beta subunit of Saccharomyces cerevisiae casein kinase II (CKII). Deletion of CKII regulatory subunits elicits a salt-sensitive phenotype. J. Biol. Chem. 270:10395-10404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheng, P., Y. Yang, K. H. Gardner, and Y. Liu. 2002. PAS domain-mediated WC-1/WC-2 interaction is essential for maintaining the steady state level of WC-1 and the function of both proteins in circadian clock and light responses of Neurospora. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:517-524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheng, P., Y. Yang, C. Heintzen, and Y. Liu. 2001. Coiled-coil domain mediated FRQ-FRQ interaction is essential for its circadian clock function in Neurospora. EMBO J. 20:101-108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheng, P., Y. Yang, and Y. Liu. 2001. Interlocked feedback loops contribute to the robustness of the Neurospora circadian clock. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:7408-7413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheng, P., Y. Yang, L. Wang, Q. He, and Y. Liu. 2003. WHITE COLLAR-1, a multifunctional Neurospora protein involved in the circadian feedback loops, light sensing, and transcription repression of wc-2. J. Biol. Chem. 278:3801-3808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Collett, M. A., N. Garceau, J. C. Dunlap, and J. J. Loros. 2002. Light and clock expression of the Neurospora clock gene frequency is differentially driven by but dependent on WHITE COLLAR-2. Genetics 160:149-158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crosthwaite, S. K., J. C. Dunlap, and J. J. Loros. 1997. Neurospora wc-1 and wc-2: transcription, photoresponses, and the origins of circadian rhythmicity. Science 276:763-769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crosthwaite, S. K., J. J. Loros, and J. C. Dunlap. 1995. Light-induced resetting of a circadian clock is mediated by a rapid increase in frequency transcript. Cell 81:1003-1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davis, R. L., and D. deSerres. 1970. Genetic and microbial research techniques for Neurospora crassa. Methods Enzymol. 27A:79-143. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Denault, D. L., J. J. Loros, and J. C. Dunlap. 2001. WC-2 mediates WC-1-FRQ interaction within the PAS protein-linked circadian feedback loop of Neurospora. EMBO J. 20:109-117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dunlap, J. C. 1999. Molecular bases for circadian clocks. Cell 96:271-290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Edery, I., L. Zweibel, M. Dembinska, and M. Rosbash. 1994. Temporal phosphorylation of the Drosophila period protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:2260-2264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eide, E. J., E. L. Vielhaber, W. A. Hinz, and D. M. Virshup. 2002. The circadian regulatory proteins BMAL1 and cryptochromes are substrates of casein kinase Iɛ. J. Biol. Chem. 277:17248-17254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Froehlich, A. C., Y. Liu, J. J. Loros, and J. C. Dunlap. 2002. White Collar-1, a circadian blue light photoreceptor, binding to the frequency promoter. Science 297:815-819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garceau, N., Y. Liu, J. J. Loros, and J. C. Dunlap. 1997. Alternative initiation of translation and time-specific phosphorylation yield multiple forms of the essential clock protein FREQUENCY. Cell 89:469-476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gorl, M., M. Merrow, B. Huttner, J. Johnson, T. Roenneberg, and M. Brunner. 2001. A PEST-like element in FREQUENCY determines the length of the circadian period in Neurospora crassa. EMBO J. 20:7074-7084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.He, Q., P. Cheng, Y. Yang, L. Wang, K. H. Gardner, and Y. Liu. 2002. White collar-1, a DNA binding transcription factor and a light sensor. Science 297:840-843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Iwasaki, H., S. B. Williams, Y. Kitayama, M. Ishiura, S. S. Golden, and T. Kondo. 2000. A kaiC-interacting sensory histidine kinase, SasA, necessary to sustain robust circadian oscillation in cyanobacteria. Cell 101:223-233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kloss, B., J. L. Price, L. Saez, J. Blau, A. Rothenfluh, and M. W. Young. 1998. The Drosophila clock gene double-time encodes a protein closely related to human casein kinase Iɛ. Cell 94:97-107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kloss, B., A. Rothenfluh, M. W. Young, and L. Saez. 2001. Phosphorylation of period is influenced by cycling physical associations of double-time, period, and timeless in the Drosophila clock. Neuron 30:699-706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lakin-Thomas, P., G. Coté, and S. Brody. 1990. Circadian rhythms in Neurospora: biochemistry and genetics. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 17:365-416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee, C., J. P. Etchegaray, F. R. Cagampang, A. S. Loudon, and S. M. Reppert. 2001. Posttranslational mechanisms regulate the mammalian circadian clock. Cell 107:855-867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee, K., J. C. Dunlap, and J. J. Loros. 2003. Roles for WHITE COLLAR-1 in circadian and general photoperception in Neurospora crassa. Genetics 163:103-114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee, K., J. J. Loros, and J. C. Dunlap. 2000. Interconnected feedback loops in the Neurospora circadian system. Science 289:107-110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lin, J. M., V. L. Kilman, K. Keegan, B. Paddock, M. Emery-Le, M. Rosbash, and R. Allada. 2002. A role for casein kinase 2α in the Drosophila circadian clock. Nature 420:816-820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Linden, H., P. Ballario, and G. Macino. 1997. Blue light regulation in Neurospora crassa. Fungal Genet. Biol. 22:141-150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu, Y., N. Garceau, J. J. Loros, and J. C. Dunlap. 1997. Thermally regulated translational control mediates an aspect of temperature compensation in the Neurospora circadian clock. Cell 89:477-486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu, Y., J. Loros, and J. C. Dunlap. 2000. Phosphorylation of the Neurospora clock protein FREQUENCY determines its degradation rate and strongly influences the period length of the circadian clock. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:234-239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Loros, J. J., S. A. Denome, and J. C. Dunlap. 1989. Molecular cloning of genes under the control of the circadian clock in Neurospora. Science 243:385-388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Loros, J. J., and J. C. Dunlap. 2001. Genetic and molecular analysis of circadian rhythms in NEUROSPORA. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 63:757-794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lowrey, P. L., K. Shimomura, M. P. Antoch, S. Yamazaki, P. D. Zemenides, M. R. Ralph, M. Menaker, and J. S. Takahashi. 2000. Positional syntenic cloning and functional characterization of the mammalian circadian mutation tau. Science 288:483-492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Luo, C., J. J. Loros, and J. C. Dunlap. 1998. Nuclear localization is required for function of the essential clock protein FREQUENCY. EMBO J. 17:1228-1235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martinek, S., S. Inonog, A. S. Manoukian, and M. W. Young. 2001. A role for the segment polarity gene shaggy/GSK-3 in the Drosophila Circadian Clock. Cell 105:769-779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Meggio, F., O. Marin, and L. A. Pinna. 1994. Substrate specificity of protein kinase CK2. Cell Mol. Biol. Res. 40:401-409. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Merrow, M., L. Franchi, Z. Dragovic, M. Gorl, J. Johnson, M. Brunner, G. Macino, and T. Roenneberg. 2001. Circadian regulation of the light input pathway in Neurospora crassa. EMBO J. 20:307-315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pinna, L. A., and F. Meggio. 1997. Protein kinase CK2 (“casein kinase-2”) and its implication in cell division and proliferation. Prog. Cell Cycle Res. 3:77-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Price, J. L., J. Blau, A. Rothenfluh, M. Adodeely, B. Kloss, and M. W. Young. 1998. double-time is a new Drosophila clock gene that regulates PERIOD protein accumulation. Cell 94:83-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Roussou, I., and G. Draetta. 1994. The Schizosaccharomyces pombe casein kinase II alpha and beta subunits: evolutionary conservation and positive role of the beta subunit. Mol. Cell. Biol. 14:576-586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schwerdtfeger, C., and H. Linden. 2000. Localization and light-dependent phosphorylation of white collar 1 and 2, the two central components of blue light signaling in Neurospora crassa. Eur. J. Biochem. 267:414-422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Selker, E. U., and P. W. Garrett. 1988. DNA sequence duplications trigger gene inactivation in Neurospora crassa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 85:6870-6874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sugano, S., C. Andonis, R. Green, Z. Y. Wang, and E. M. Tobin. 1998. Protein kinase CK2 interacts with and phosphorylates the Arabidopsis circadian clock-associated 1 protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:11020-11025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sugano, S., C. Andronis, M. S. Ong, R. M. Green, and E. M. Tobin. 1999. The protein kinase CK2 is involved in regulation of circadian rhythms in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 96:12362-12366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Talora, C., L. Franchi, H. Linden, P. Ballario, and G. Macino. 1999. Role of a white collar-1-white collar-2 complex in blue-light signal transduction. EMBO J. 18:4961-4968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Toh, K. L., C. R. Jones, Y. He, E. J. Eide, W. A. Hinz, D. M. Virshup, L. J. Ptacek, and Y. H. Fu. 2001. An hPer2 phosphorylation site mutation in familial advanced sleep phase syndrome. Science 291:1040-1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vielhaber, E., E. Eide, A. Rivers, Z. H. Gao, and D. M. Virshup. 2000. Nuclear entry of the circadian regulator mPER1 is controlled by mammalian casein kinase I epsilon. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:4888-4899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yang, Y., P. Cheng, and Y. Liu. 2002. Regulation of the Neurospora circadian clock by casein kinase II. Genes Dev. 16:994-1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yang, Y., P. Cheng, G. Zhi, and Y. Liu. 2001. Identification of a calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase that phosphorylates the Neurospora circadian clock protein FREQUENCY. J. Biol. Chem. 276:41064-41072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Young, M. W., and S. A. Kay. 2001. Time zones: a comparative genetics of circadian clocks. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2:702-715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]