Abstract

The Aspergillus allergen Asp f16 has been shown to confer protective Th1 T cell-mediated immunity against infection with Aspergillus conidia in murine models. Here, we use overlapping (11-aa overlap with preceding peptide) pentadecapeptides spanning the entire 427-aa coding region of Asp f16 presented on autologous dendritic cells (DC) to evaluate the ability of this antigen to induce Th1 responses in humans. Proliferative responses were induced in five out of five donors, and one line with a high frequency of interferon (IFN)-γ-producing CD4+ T cells in response to the complete peptide pool was characterized. This line was cytotoxic to autologous pool-pulsed and Aspergillus culture extract-pulsed targets. Limitation of cytotoxicity to the CD4+ T cell subset was demonstrated by co-expression of the degranulation marker CD107a in response to peptide pool-pulsed targets. Cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL) killed Aspergillus hyphae and CTL culture supernatant killed Aspergillus conidia. By screening 21 smaller pools and individual peptides shared by positive pools we identified a single candidate sequence of TWSIDGAVVRT that elicited responses equal to the complete pool. The defined epitope was presented by human leucocyte antigen (HLA)-DRB1-0301. These data identify the first known Aspergillus-specific T cell epitope and support the use of Asp f16 in clinical immunotherapy protocols to prime protective immune responses to prevent or treat Aspergillus infection in immunocompromised patients.

Keywords: Aspergillus fumigatus, CTL, immunotherapy, pentadecapeptides

Introduction

Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis (IPA) is a primary cause of morbidity and mortality in immunocompromised patients, with Aspergillus fumigatus as the organism most often implicated (reviewed in [1]). A. fumigatus infection is especially prevalent in recipients of haematopoietic stem cell transplants (HSCT), solid organ transplant patients, and patients undergoing therapy for the treatment of cancer [1–4]. The overall mortality from untreated IPA approaches 85%. Even with treatment, mortality may be as high as 50%[5,6]. The most important risk factor for IPA has historically been neutropenia. However, there is increasing clinical evidence that the adaptive immune response also plays a critical role [7]. There has been a clear increase in the frequency of Aspergillus infections in the setting of immune deficiency secondary to haematological malignancies and HSCT that cannot be strictly attributed to neutropenia [1]. Indeed, a prime correlate to the risk of Aspergillus infection for HSCT patients is prolonged immune suppression due either to the transplant conditioning and graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) prophylaxis or secondary to GVHD and its treatment [4,8–13]. T cells and T cell function recover slowly over the first few months post-HSCT while neutrophil recovery generally occurs within the first 2–3 weeks. T cell reconstitution is further impaired in allograft recipients because therapies for the prevention or treatment of GVHD are nearly all targeted at T cells. Furthermore, GVHD itself can directly hinder T cell reconstitution by damaging lymphoid organs, including the thymus that is needed for T cell redevelopment from stem cell precursors (reviewed in [14]). Evidence that Th1/Th2 dysregulation and a switch to Th2 immune response contribute to the development and unfavourable outcome of IPA confirms the crucial role of a Th1 reactivity in the control of Aspergillusinfection [15,16]. An increased ratio of IFN-γ: Interleukin (IL)-10 in response to Aspergillus antigens by peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) from HSCT patients was associated with a favourable response to antifungal therapy, suggesting that here too a Th1 response may be beneficial [17]. Despite improved diagnostic tests and the wide use of antifungal prophylaxis, most cases of IPA remain undiagnosed and untreated at death. Therefore development of additional therapies directed toward the augmentation of host defence mechanisms against A. fumigatus, to overcome the potential effects of T cell deficiency on immune reconstitution post-transplant, is urgently needed [18–20].

Most published studies designed to induce immune response to A. fumigatus, including our own [21], have used crude extracts from mycelia, spores and whole culture filtrates [18]. Such preparations contain, in addition to the relevant antigens, a large number of non-antigenic components including carbohydrates, proteins, nucleic acids and even toxins [22,23]. The major disadvantage to these extracts is the inability to standardize the preparations or prepare them in a manner that would be suitable for clinical use [24,25]. Currently, 23 recombinant A. fumigatus allergens associated with allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA) have been identified and characterized (IUIS official list of allergens: http://www.allergen.org). Most of the identified allergens elicit humoral immune responses [26–29], others are toxic to PBMC or are strongly homologous to human proteins, while some appear to prime primarily a Th2 T cell response [30–33]. Two allergens have been shown to stimulate both T and B cell responses from patients with ABPA, Asp f2 and Asp f16 [34,35]. Both have been tested for their ability to confer protective immunity in mice challenged with Aspergillus conidia and in this setting Asp f16 was uniquely able to act as immunodominant antigen in both the inductive and expressive phases of delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions and was associated with the induction of a Th1 T cell response [16]. For these reasons we focused our further efforts to develop novel immunotherapeutic approaches to Aspergillus infection on Asp f16.

The effectiveness of determining T cell epitopes and CD8+/CD4+ T cell frequencies against viral antigens by use of protein-spanning pools of overlapping pentadecapeptides, with each 15 amino acids (aa) peptide overlapping the previous peptide by 11-aa, has been described recently [36–38]. Based on these results, we prepared a series of 104 overlapping pentadecapeptides spanning the entire 427-aa coding region of Asp f16 and used a complete pentadecapeptide pool (Asp f16-PPC) pulsed onto dendritic cells (DC) to prime autologous proliferative and cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) responses. For this purpose we used fast-DC derived from monocytes (Mo) in 2–3 days that were found previously by our laboratory to be as effective as standard-DC in the generation of Aspergillus- and CMV (cytomegalovirus)-specific T cell responses [21]. We found that Asp f16 is capable of inducing proliferative and cytotoxic Th1 T cell responses directed to a human leucocyte antigen (HLA) Class II restricted epitope from the Asp f16 allergen.

Materials and methods

Asp f16-spanning pools of overlapping pentadecapeptides

A complete pool of 11-aa overlapping pentadecapeptides spanning the entire protein of Asp f16 was used in our study to generate Aspergillus-specific T cell responses. A total of 104 pentadecapeptides are required to overspan the entire Asp f16 protein. The sequence of the first peptide is MYFKYTAAALAAVLP (aa 1–15), the second peptide overlaps the first by 11-aa, YTAAALAAVLPLCSA (aa 5–19), and the third overlaps the second peptide by 11-aa, ALAAVL PLCSAQTWS (aa 9–23). Immunograde peptides were synthesized and analysed by NMI Technologietransfer GmbH (Reutlingen, Germany). Peptides were dissolved in dimethyl sulphoxide (DMSO, Edwards Lifesciences, Bedford, OH, USA) at 10 mg/ml and stored in small single-use aliquots at −70°C. Twenty-one small pools consisting of 4–11 pentadecapeptides arranged in a matrix such that each pentadecapeptide was represented in two pools, one vertical and one horizontal, were used to identify Asp f16-epitopes responsible for the induced immune response.

Generation and pulsing of fast-DC with Asp f16-PPC

Fast-DC were prepared from adherent blood Mo as previously described [21]. Starting material was PBMC obtained by aphereses from five normal donors after written informed consent under research protocols approved by the Medical College of Wisconsin and Froedtert Hospital Investigational Review Boards. The PBMC were frozen in multiple small aliquots in RPMI complete medium (RPMI-1640 with 25 m m HEPES, 2 mm l-glutamine, BioWhittaker, Walkersville, MD, USA) with 20% pooled human AB serum (HS, Labquip Ltd, Niagara Falls, NY, USA) and 10% DMSO. Immature DC were generated in 2–3 days by culture with 800 U/ml granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF) (Immunex, Seattle, WA, USA) and 1000 U/m IL-4 (R&D Systems, Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA) then pulsed for 6 h with Asp f16-PPC, and matured for 2 days with a mixture of 10 ng/ml IL-1β, 1000 U/ml IL-6, 10 ng/ml tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α (all from R&D Systems, Inc.) and 1 µg/ml prostaglandin (PG)-E2 (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA). Mature, pulsed fast-DC were then used to prime proliferative and CTL responses.

T cell proliferation assay

Proliferation in response to soluble Asp f16-PPC ± IL-2 was performed as follows: 1 µg/ml Asp f16-PPC was added to the wells of 96-well round-bottomed plates containing 105 PBMC. Cells were cultured in 0·2 ml RPMI-10% pooled HS at 37°C and 5% CO2 for 5 days prior to the addition of [3H]-thymidine (1 µCi/well Na2−51CrO4, ICN Pharmaceuticals, Costa Mesa, CA, USA). IL-2, at 200 IU/ml (Chiron, Emeryville, CA, USA) was added to some wells at day 3. Positive and negative controls wells included PBMC with 10 µg/ml phytohaemaglutinin (PHA, Difco Laboratories, Detroit, MI, USA) or medium, respectively. The cultures were harvested 18 h after adding [3H]-thymidine, onto glass fibre paper using a 96-well cell harvester, and the radioactivity counted in a β-scintillation counter (Packard, Meriden, CT, USA). SI was calculated as: Decreasing numbers of 25 Gy-irradiated, PPC-pulsed or non-pulsed, mature fast-DC were cultured in RPMI-10% HS at 37°C and 5% CO2 with 105 autologous Mo-depleted PBMC in 96-well round-bottomed plates for 5 days prior to the addition of 1 µCi [3H]-thymidine. Wells containing irradiated stimulator cells or responders alone were included as negative controls. Proliferation was assessed as above by [3H]-thymidine uptake for 18 h. SI was calculated as: The results were expressed as the mean value of triplicate samples of five donors ± s.d.

Generation of Aspergillus-specific T cell lines

Irradiated (25 Gy), mature, antigen-pulsed fast-DC were co-cultured with autologous lymphocytes at ratio 1 : 10 (stimulators : responders) to generate Aspergillus-specific bulk-cultures as previously described [21]. A total of 500 pg/ml IL-12 (R&D Systems, Inc.) was added to the culture to increase IFN-γ secretion from natural killer (NK) and T cells, which promotes the development of Th1 immune responses [39,40]. Cells were adjusted to 106 cells/ml and maintained at this concentration throughout the culture period. Cultures were fed every third day with half-fresh media, RPMI-10% pooled HS and 200 IU/ml IL-2. The cultures were restimulated weekly.

Intracellular IFN-γ and IL-4 detection assay

Intracellular IFN-γ and IL-4 production of T cells was determined using FastImmune Intracellular Cytokine Detection Kits (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA). Effectors (106/ml) were incubated with co-stimulatory molecules CD28 and CD49d and antigen at 37°C and 5% CO2 in 15 ml sterile propylene tubes. After 1 h Brefeldin A (10 mg/ml, Sigma) was added to inhibit cytokine secretion and the tubes incubated for additional 5 h. Tubes were then transferred to a water bath (18°C) and incubated overnight. Staining and flow analysis were performed according to the manufacture's recommendations and as described previously [41]. Effectors incubated with either staphylococcal enterotoxin B superantigen (SEB, Sigma) or no antigens were considered as positive and negative controls, respectively, for the assay.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent (ELISPOT) assay

The frequency of Asp f16-specific IFN-γ-producing cells in PBMC from normal donors was determined by ELISPOT assay as follows: 96-well MultiScreen IP ELISPOT plates (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA) were coated with capture antibodies to IFN-γ (Endogen, Woburn, MA, USA) overnight at 4°C, washed several times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, BioWhittaker) and then blocked for 1 h with RPMI-10% HS. PBMC (4 × 106/ml) from healthy donors were stimulated with 2 mg/ml of single pentadecapeptide or 1 mg/ml of the complete pentadecapeptide pool for 2 h at 37°C. The PBMC were serially diluted (1 : 2) and 0·1 ml added to the wells in triplicate. The plates were incubated for 24 h in a humidified atmosphere at 37°C with 5% CO2. One mg/ml SEB was used as a positive control and PBMC in the absence of peptide were used as the background control. Following incubation, the plates were washed with PBS-1% Tween 20 (Sigma) and incubated overnight at 4°C with biotinylated detection antibody (Endogen) at 1 mg/ml in 50 µl of PBS, washed and incubated 60 min at room temperature with 1 : 10000 diluted avidin-alkaline phosphatase (Sigma). The wells were again washed and the colour developed by addition of the BCIP/NBT alkaline phospatase substrate solution (Sigma) and incubated for 15–60 min at room temperature in a dark area. Colour development was stopped by washing under running deionized water. After drying overnight at room temperature, coloured spots were counted by ImmunoSpotTM Series 1 Analyser and supporting ImmunoSpotTM software (Cellular Technology).

Cytotoxic T cell assay and determination of HLA-restriction

Cytotoxicity of Asp f16 bulk-cultures was measured by 51Cr-release assay at multiple effector to target cell ratios as described previously [21]. Targets included autologous DC or PHA blasts and autologous and partially HLA-matched B lymphoblastoid cell lines (BLCL). Additional targets such as the NK-sensitive cell line K562 (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA, USA) were also used. Targets were either un-pulsed, or pulsed with A. fumigatus commercial culture filtrate antigen (Asp f-CF, Greer Laboratories, Inc., Lenoir, NC, USA), Asp f16-PPC, one of the small peptide pools or with single peptides. HLA-typed BLCL were either homozygous cell lines used in the 10th International Histocompatibility workshop, or were BLCL prepared under experimental protocols from patients or donors undergoing allogenic HSCT. Consent was obtained at the time of sample collection for use of patient and donor BLCL for other experimental protocols. Spontaneous release was measured using medium with targets (no effectors) and maximum release was measured using 0·5% Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich Corp) with targets only. Specific lysis was calculated as:

Conidiacidal assay

A. fumigatus isolates were maintained on Sabouraud/Dextrose agar supplemented with antibiotics. Conidia were harvested by gently scraping the plates with a sterile transfer pipette, flooding the plates with sterile RPMI and then filtering the solution through sterile gauze. Conidia were incubated for 2 h at room temperature in RPMI medium before labelling. Live and heat inactivated (85°C for 30 min) conidia were labelled in the dark with a fluorescent molecular stain (FUN-1, Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA) at 25 µm with gentle shaking at room temperature for 45 min, washed twice with RPMI, adjusted to 106 conidia/ml, and stored at 4°C as described previously [42]. CTL were restimulated 24 h prior to collection of culture supernatant for the assay. FUN-1 stained live conidia (106) were incubated overnight in fresh RPMI culture medium (no CTL) or in cell-free CTL culture medium (1 ml) and then examined under fluorescence microscope. Metabolically active conidia accumulate orange fluorescence in vacuoles, while dormant and dead conidia stain green.

Hyphae killing assay

Hyphae killing was determined by using a tetrazolium dye XTT as described previously [43], with some modifications. Briefly, Aspergillus conidia (1·5 × 106) were germinated (to form hyphae) in 1·0 ml RPMI at 45°C in a 2·0 ml microcentrifuge tube (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburg, PA, USA) for 16 h. Asp f16-specific CTL or CMVpp65-specific CTL were added to hyphae (effector : hyphae ratio of 3 : 1) and incubated at 37°C for 2 h (with continued mixing) in the presence or absence of 1 µg/ml Asp f16-PPC or pp65 peptide mix (Jerini Peptide Technologies, Berlin, Germany). Tubes containing live hyphae, CTL and 10% formaldehyde-killed hyphae alone were included as controls. After lysis of CTL by addition of 1 ml ice-cold distilled water, tubes were mixed vigorously by vortex and centrifuged at 4°C for 10 min at 3000 g. Then 400 µl of freshly prepared XTT (0·5 mg/ml, Sigma) containing Coenzyme Q (40 µg/ml, Sigma) were added to the tubes and incubated for 1 h at 37°C with continued mixing. One hundred µl, supernatant from each tube was placed in a flat-bottomed 96-well plate and absorption at 450 nm was determined with 96-well plate reader (Packard). Absorption of each well at 650 nm was also obtained to control non-specific absorption. The percentage of fungal cell damage was defined by the following equation:

FACS analysis and monoclonal antibodies (MoAb)

Approximately 0·25 × 106 cells/tube were immunophenotyped using a four-colour direct panel including FITC-, PE-, PerCP- and APC-conjugated MoAb to: CD1a, CD3, CD4, CD8, CD14, CD19, CD40, CD45, CD56, CD69, CD83, CD86, CD107a, HLA-DR, IFN-γ, IL-4, TCR-α/β and TCR-γ/δ, with the relevant isotype controls. All antibodies were obtained from Becton-Dickenson (Hialeah, FL, USA). The stained cells were acquired on a FACSCalibur flow cytometer and were analysed from list mode data using the fcap software package.

Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed with the unpaired t-test and one-way anova (and non-parametric) test using GraphPad Prism version 3·0 for Macintosh (GraphPad software, San Diego, CA, USA) to compare between two or more groups, respectively. P-values of <0·05, <0·01 and <0·001 were considered statistically significant, highly significant and very highly significant, respectively.

Results

Proliferative response to Asp f16-PPC requires prior presentation on DC

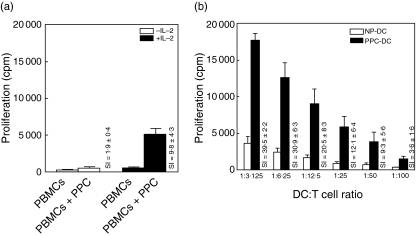

Previously, we found that PBMC cells of healthy donors proliferated well to Asp f-CF presented by autologous monocyte-derived DC that were generated in as few as 3 days (fast-DC) [21] but responded poorly to soluble antigen in the absence of added DC. To determine whether direct exposure to soluble Asp f16-PPC induces a specific lymphoproliferative response, PBMC from five healthy donors were stimulated with 1 mg/ml Asp f16-PPC ± IL-2 (added on day 3). While no marked T cell proliferation (SI = 1·9 ± 0·4) was detected in response to soluble Asp f16-PPC in the absence of IL-2, proliferation was significantly increased (SI = 9·8 ± 4·3, P < 0·05, unpaired t-test) in the presence of IL-2 (Fig. 1a). Presentation on mature fast-DC further increased the proliferative response to Asp f16-PPC (SI = 39·5 ± 2·2 at a DC : T ratio of 1 : 3), as illustrated in Fig. 1b. This increase was significant (P < 0·001, one-way analysis of variance) for all donors compared to proliferation to soluble antigen in the absence of IL-2 at all DC : T cell ratios and was significantly higher at DC : T cell ratios of 1 : 3 and 1 : 6 compared to stimulation with soluble antigen in the presence of IL-2. The proliferative response induced by PPC-pulsed DC was significantly higher (P > 0·05, unpaired t-test) than that induced by Asp f-CF pulsed fast-DC (not shown).

Fig. 1.

Proliferative response to Asp f16 protein-derived overlapping pentadecapeptides. (a) PBMC from five different donors were stimulated with soluble Asp f16-PPC (not presented on autologous DC) in the presence or absence of IL-2 added at day 3 of a 6-day culture. Data are presented as the counts per minute (cpm) [3H]-thymidine uptake and as the stimulation index (SI) of triplicate cultures from all five doors compared to PBMC alone. (b) Proliferation in response to autologous PPC-pulsed fast-DC (PPC-DC). Decreasing numbers of 25 Gy-irradiated, PPC-pulsed or non-pulsed (NP-DC), mature fast-DC from the same five donors were cultured with autologous lymphocytes for 6 days. Data are presented as the mean cpm and as the SI index of triplicate cultures from all five donors at the indicated DC : T cell ratios. Asp f16-PPC: complete pool of Asp f16 protein-derived overlapping pentadecapeptides.

PPC-pulsed fast-DC after maturation were CD14–, loosely adherent and developed the typical morphology, cytoplasmic projections and surface markers with high expression (80–100%) of CD40, CD45, CD83, CD86 and HLA-DRbright and low expression (2–7%) of CD14 and CD1a characteristic for mature monocyte-derived DC. There were no significant differences in the appearance or surface phenotype of antigen pulsed versus non-pulsed DC. All these results illustrated that Asp f16-derived pentadecapeptides were of a size that can be processed and presented by fast-DC for the generation of T cell specific proliferative responses. In addition, the data showed the important role of DC to initiate and increase the proliferative response to A. fumigatus.

Induction of Aspergillus-specific CD4+ Th1 T cell responses by Asp f16-PPC pulsed fast-DC

Asp f16-effectors were generated by repeated weekly stimulations with autologous mature PPC-pulsed fast-DC. Intracellular IFN-γ and IL-4 production, cytolytic activity and phenotypic features of the lines were assessed weekly. At week 3 a T cell line from one donor, RD0308, had a high frequency of IFN-γ-producing CD4+ T cells (22·7 ± 3·8%) in response to Asp f16-PPC compared to stimulation with a control antigen, SEB (2·1 ± 2·8) or unstimulated effectors (0·05 ± 0·04). CD4+ T cells producing IFN-γ increased steadily with repeated priming and represented 33·8 ± 3·3% of the culture at week 5 and 61·1 ± 4·0% by week 7. The percentage of total T cells and CD4+ T cells producing IFN-γ in fresh PBMC from donor RD0308 in response to Asp f16-PPC were 0·17% and 0·15%, respectively. Almost all the T cells that proliferated in response to Asp f16-PPC were CD4+ (>95·0%) as determined by CD69 expression. No detectable intracellular IFN-γ was produced by CD8+ T cells. In addition IL-4 was not detected in unstimulated effectors or in response to Asp f16-PPC or SEB, indicating that a Th1 immune response was induced by Asp f16-PPC.

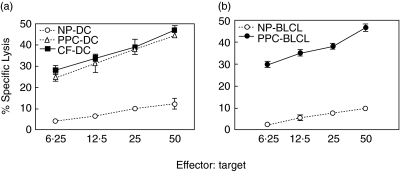

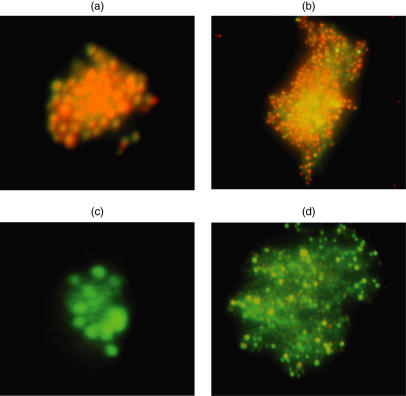

Cytolytic activity of the effectors was assessed by 51Cr release assay. Autologous PPC-pulsed targets including fast-DC and BLCL in addition to Aspergillus culture extract-pulsed fast-DC were lysed (Fig. 2). No significant lytic activity was seen using autologous non-pulsed targets (Fig. 2), autologous PHA blasts or the NK-sensitive cell line K562 as specificity controls (not shown). Phenotypic analysis of the bulk-culture revealed a mixture of CD3+/CD4+ and CD3+/CD8+ cells. CD4+ T cells increased steadily from 87·1 ± 3·3% at week 3–96·4 ± 2·1 at week 5 and almost all effectors became CD4+ T cells (99·2 ± 0·7%) at week 7. Limitation of cytotoxicity to the CD4+ T cell subset was demonstrated by co-expression of the degranulation marker CD107a on 23% of CD4+ T cells in response to PPC-pulsed targets. No significant increase in CD107a was seen for CD8+ subset in response to PPC-pulsed targets. The ability of the CTL effectors to kill fresh Aspergillus conidia was assessed using a FUN-1 conidiacidal assay. Metabolically active live conidia accumulate orange fluorescence in vacuoles (Fig. 3a), whereas dormant, heat-killed conidia stain green (Fig. 3b). Our data showed that fresh culture medium had no harmful effect on live conidia (Fig. 3c), while supernatant from the CTL-culture killed fresh Aspergillus conidia (Fig. 3d). This assay cannot be used with cells in the cultures as they also take up the FUN-1 dye, but killing by the CTL line of hyphae was tested using an XTT dye reduction assay. CTL from RD0308 resulted in 12·5 ± 0·6% killing that increased to 19·9 ± 0·7% killing when Asp f16-PPC was added to the culture. In contrast, a CMV-specific T cell line generated by priming with DC pulsed with a pool of peptides from pp65 failed to result in any significant hyphae killing with or without added pp65 peptide pool. Formalin-killed hyphae showed 99·0 ± 0·4% killing. These data are shown in Table 1. All these results indicated that Aspergillus-specific cytotoxic CD4+ Th1 T cells were generated by using PPC-pulsed fast-DC.

Fig. 2.

Lytic activity of the Asp f16-specific T cell line. Asp f16-effectors were generated by three stimulations with autologous, mature, Asp f16-PPC-pulsed fast-DC. Cytolytic activity of the culture was assessed 5 days thereafter by chromium release using autologous non-, Asp f16-PPC- and CF-pulsed DC (a) or non- and Asp f16-PPC-pulsed BLCL (b) as targets. Data are presented as mean value of triplicate wells ± s.d. There was no significant difference in lytic activity towards CF- and PPC-pulsed targets (P > 0·05, one-way analysis of variance). NP: non-pulsed; PPC: complete overlapping pentadecapeptides pool; CF: commercial Aspergillus culture-filtrate antigen.

Fig. 3.

Conidiacidal activity of Asp f16-specific T cell line bulk-culture supernatant. Live and heat-inactivated conidia were labelled with a fluorescent molecular stain (FUN-1). Asp f16-effectors were restimulated 48 h prior to the assay. FUN-1-stained live conidia (106) were incubated overnight in fresh RPMI-1640 culture medium or in CTL culture medium. Wells containing live and heat-inactivated FUN-1-labelled conidia alone were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. Metabolically active conidia accumulate orange fluorescence in vacuoles, while dormant and dead conidia stain green. FUN-1-stained live conidia (a), FUN-1-stained dead conidia (b), FUN-1-stained live conidia in fresh RPMI-1640 culture medium (c) and FUN-1-stained live conidia in Asp f16-CTL culture medium (d).

Table 1.

XTT hyphae killing assay.

| Effectors | % Hyphae damage |

|---|---|

| Asp f16-CTL | 12·5 ± 0·6 |

| Asp f16-CTL + Asp f16-PPC | 19·9 ± 0·7 |

| pp65-CTL | 2·6 ± 0·5 |

| pp65-CTL + pp65-PM | 3·0 ± 0·2 |

| Formalin | 99·0 ± 0·4 |

Asp f16-specific CTL on day 6 after the last priming were tested in an XTT hyphae killing assay after a 2-h exposure of effectors to hyphae at a ratio of 3 : 1. Hyphae killing was tested in the absence or presence of added Asp f16 complete peptide pool (Asp f16-PPC). A CTL line specific for CMV pp65 was included as a control in the absence or presence of added peptide mix containing overlapping pentadecapeptides spanning the coding region of pp65 (pp65-PM). Data are presented as the mean value±s.d. of triplicate assays.

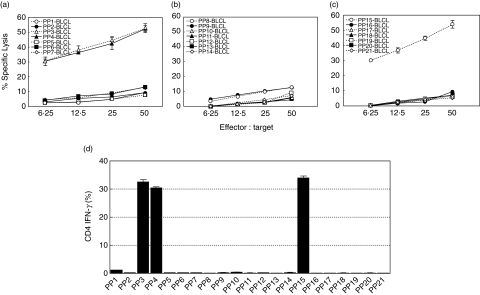

A single HLA Class II restricted Asp f16-epitope was responsible for both CTL activity and IFN-γ production of the generated effectors

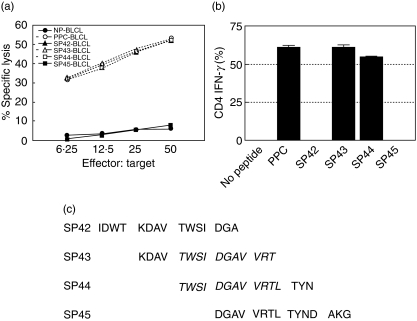

To define the epitope(s) inducing the Asp f16-specific response, we screened 21 smaller pools containing 4–11 pentadecapeptides each using both cytolytic activity and intracellular IFN-γ production assays. Lytic activity and IFN-γ production was detected in response to only three smaller pools (Fig. 4). Asp f16-effectors were sensitized to the same extent by BLCL pulsed with PP3, PP4 and PP15 (P > 0·05, one-way analysis of variance). The shared peptides between the pools were SP43 and SP44. To confirm the peptide specificity we performed individual CTL assays using autologous BLCL pulsed with peptides SP42-SP45. No lytic activity or IFN-γ production was seen in response to SP42 or SP45 (Fig. 5a,b), whereas the effectors did recognize SP43 and SP44. This result confirms that the Asp f16-epitope is contained in SP43 and SP44. These pentadecapeptides share the amino acid sequence TWSIDGAVVRT as shown in Fig. 5c, indicating that the specific peptide is contained within that sequence.

Fig. 4.

Screening with small peptide pools. The Asp f16-specific T cell line was screened using 21 smaller pools containing 4–11 peptides in 51Cr release assays (a, b, c) and in intracellular IFN-γ production assays (d). Reactivity was seen to only three smaller pools. Data are presented as mean values ± s.d. of triplicate assays. Asp f16-effectors were sensitized only and to the same extent to PP3, PP4, and PP15 (P > 0·05, one-way analysis of variance). Thus, the recognized Asp f16 epitope should be in SP43 and SP44. PP: peptide pool; SP: single peptide.

Fig. 5.

Asp f16 epitope. Asp f16 bulk-culture showed lytic activity (a) and IFN-γ production (b) in response to single peptides sharing the epitope. Data are presented as mean values ± s.d. The effectors were not sensitive to SP42 and SP45 indicating that the epitope is contained in SP43 and SP44. There was no significant difference (P > 0·05, one-way analysis of variance) in lytic activity and IFN-γ production in response to either PPC, SP43 or SP44. The shared amino acid sequence between SP43 and SP44 is TWSIDGAVVRT (c). PP: peptide pool; SP: single peptide.

The HLA type of the donor RD0308 was determined by DNA sequencing to be: A-1101, B-0801, B-3501, C-0401, C07/06, DRB1-0101, DRB1-0301, DRB3-01, DQ-0201 and DQ-0501. To determine the HLA allele restricting the response, Asp f16-PPC pulsed BLCL matched with the effectors for only one or more HLA alleles were used in cytotoxic assay. As shown in Table 2, Asp f16-effectors were cytotoxic for PPC-pulsed DRB1-0301+ targets but not for PPC-pulsed DRB1-0301– targets, indicating that the epitope was presented by HLA-DRB1-0301. A database search of peptides likely to be restricted to DRB1-0301 identified the probable epitope as WSIDGAVVR (position 174–182) [44].

Table 2.

Asp f16-effectors response was restricted by HLA-DRB1-0301.

| PPC-BLCL | Shared HLA Class I alleles | Shared HLA Class II alleles | % Lytic activity (E : T ratio = 50 : 1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| TJ | A-1101 | 5·2 ± 1·3 | |

| MGAR | B-0801, C-07 | 5·4 ± 0·3 | |

| RD0309 | B-3501, C-0401 | DRB1-0101, DQ-0501 | 10·7 ± 1·0 |

| SS | C-0401 | DRB3-01 | 8·4 ± 0·3 |

| 035-3356-9 | C-06 | 7·2 ± 0·6 | |

| 008-1002-8 | C-06 | DQ-0201 | 6·4 ± 1·0 |

| 065-6557-6 | C-07 | 10·1 ± 0·5 | |

| ZHI-792 | C-07 | DRB3-01, DQ-0501 | 10·3 ± 0·3 |

| RJ | DRB1-0101 | 6·5 ± 2·6 | |

| L0081785 | DRB1-0301, DQ-0201 | 53·9 ± 4·9 | |

| RD0308 | All | All | 54·2 ± 3·5 |

The HLA type of the CTL donor was A-1101, B-0801, B-3501, C-0401, C07/06, DRB1-0101, DRB1-0301, DRB3-01, DQ-0201 and DQ-0501. Asp f16-PPC pulsed BLCL matched with the effectors for only the indicated HLA alleles were used in cytotoxic assay to identify the HLA-alleles restricting for the lytic activity of the bulk-cultures. Only targets sharing HLA-DRB1-0301 were lysed.

Frequency of PBMC in normal donors reactive to peptide epitope WSIDGAVVR

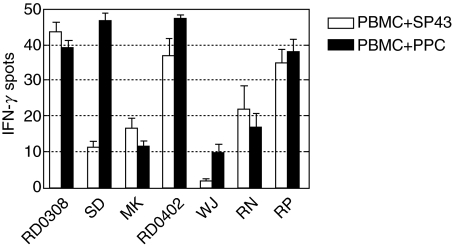

To determine the frequency of unprimed PBMC capable of a Th1 response to epitope WSIDGAVVR, we selected six HLA-DRB1-0301+ normal donors from whom cryopreserved PBMC were available in addition to donor RD0308 and screened for IFN-γ production by ELISPOT. All the donors responded to the Asp f16-PPC, with a frequency ranging from 10 to 48 IFN-γ-producing cells per 105 PBMC, as shown in Fig. 6. All except one normal HLA-DRB1-0301+ donor responded to SP43 and this donor also responded weakly to Asp f16-PPC (10 cells/105 PBMC), although the PBMC from this donor did respond to SEB (2000 cells/105 PBMC). Five of the seven donors tested, including the CTL donor RD0308, had a frequency of response to SP43 that was similar to the response to Asp f16-PPC, suggesting that WSIDGAVVR was the immunodominant peptide to which these individuals were responding. One donor, donor SD, had a significantly higher response to Asp f16-PPC compared to SP43, 47 cells/105 PBMC compared to 11 cells/105, respectively, indicating the presence of precursors capable of responding to additional epitopes present in the peptide pool.

Fig. 6.

Frequency of T cells in PBMC from normal DRB1-0301+ donors reactive to peptide epitope WSIDGAVVR. Cryopreserved PBMC from six HLA-DRB1-0301+ normal blood donors in addition to donor RD0308 were stimulated with peptide SP43 containing WSIDGAVVR and with the complete Asp f19 peptide pool and were screened for IFN-γ production by ELISPOT. Response to SEB was used as a positive control and PBMC in the absence of peptide were used as the background control. Data are expressed as the number of IFN-γ-producing cells per 105 cells plated.

Discussion

We initially screened samples from five normal adult donors for their ability to proliferate in response to the complete peptide pool from Asp f16. The PBMC from each donor proliferated well to Asp f16-PPC presented by autologous, Mo-derived, fast-DC but responded poorly to soluble Asp f16-PPC in the absence of added DC (Fig. 1), which was in accordance with our previous findings using Aspergillus culture extract [21], and indicates the important role of DC to initiate and increase the proliferative response to A. fumigatus. The proliferative response induced by PPC-pulsed DC was significantly higher (P > 0·05, unpaired t-test) than that induced by Asp f-CF-pulsed fast-DC. These data indicated that Asp f16-derived pentadecapeptides were of a size that could be processed and presented by fast-DC for the generation of T cell-specific immune responses. CTL lines were obtained from each of the first two donors that were primed with Asp f16-PPC pulsed fast-DC. A T cell line from one donor, RD0308 had a high frequency of IFN-γ-producing CD4+ T cells in response to Asp f16-PPC and was cytotoxic to autologous Asp f16-PPC- and Aspergillus culture extract-pulsed targets. Almost all the T cells activated in response to Asp f16-PPC were CD4+ (>95·0%) as determined by CD69 expression. CD4+ T cells producing IFN-γ increased steadily with repeated priming with no detectable intracellular IFN-γ produced by CD8+ T cells. IL-4 was not detected in unstimulated effectors or in response to Asp f16-PPC or SEB, indicating that a Th1 immune response was induced by Asp f16-PPC. Limitation of cytotoxicity to the CD4+ T cell subset was demonstrated by expression of the degranulation marker CD107a [45] on 23% of CD4+ T cells in response to PPC-pulsed targets. We determined the specificity of the Asp f16 response by screening each of the 21 smaller peptide pools using both IFN-γ production and lysis of autologous BLCL to narrow the reactivity to three smaller pools sharing the sequence TWSIDGAVVRT. The CTL response was found to be restricted by the donor's HLA-DRB1-0301 allele and a database search of peptides likely to bind to DRB1-0301 indicated that the recognized peptide was probably WSIDGAVVR. Asp f16 shares extensive sequence homology to Asp f9 at the N-terminal region aa 1–204 and less conserved sequence homologies at the region aa 73–204 have been seen with endo-beta glucanase and with a probable membrane protein from the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae at region 99–214 [35]. Although WSIDGAVVR is located at aa 174–182, a search for matching peptides using the Protein Information Resource program revealed that this peptide was limited to A. fumigatus[46]. Consistent with most T cell epitopes, WSIDGAVVR is composed primarily of hydrophobic aa [47].

The mechanism by which Th1+ T cells protect against infection with Aspergillus is not described fully but probably involves the stimulation of macrophage and neutrophil activity via production of IFN-γ, IL-2 and IL-12. In a reciprocal fashion, the induction of a Th2+ T cell response worsens the infection by suppressing phagocyte function secondary to the production of IL-4 and IL-10 [1]. Data from our study also indicate that Th1+ T cells may additionally mediate direct activity against Aspergillus as demonstrated by killing of fungal conidia by supernatant from the Asp f16-specific T cell line, by lysis of cells expressing the fungal peptide, and by killing of hyphae co-cultured with the CTL line. The extent of hyphae killing (20% in the presence of Asp f16-PPC) was less than that normally mediated by granulocytes using this assay (approximately 80% lysis), but appear to be specific given that a CTL line specific for CMV pp65 failed to kill hyphae at the same E : T ratio with or without added peptide. CD8+ CTL have been shown previously to partially inhibit the adherence of hyphae from Candidia albicans[48], but direct killing of fungus by CTL has not been demonstrated previously. The Asp f16-peptide-specific CTL lysed targets pulsed not only with relevant peptides but also with Aspergillus culture extracts, indicating endogenous expression of the antigenic epitope. Cytotoxic CD4+ T cell possess lytic granules containing preformed perforin and granzymes, and are able to carry out perforin-mediated cytotoxicity in the same manner as classical CD8+ cytotoxic T cells and NK cells [49]. CD4+ perforin+ T cells share phenotypic and functional characteristics with late differentiated CD8+ T cell and are present in the circulation at low numbers in healthy individuals and at relatively high levels in donors with chronic viral infection, suggesting a role of these cells in the immune response [49–51]. More than 85% of HLA-DRB1-0301+ donors tested in our study produced IFN-γ in response to peptide epitope WSIDGAVVR, with a frequency of response similar to the complete pentadecapeptides pool (Fig. 6), indicating overall high immunogenicity of this peptide.

The factors determining the differential activation of Th1 or Th2 cells by Aspergillus antigens are not fully characterized. For Asp f2, murine models showed that the Class II subtype on which the allergen is presented affected the response, with presentation on murine IA leading to a Th2 response compared to a Th1 response when presented on IE [52]. DC may play a pivotal role based on the manner in which fungal antigen is presented and the subtype of DC (DC1 versus DC2) that is involved [19]. Recent studies confirmed that the choice of receptor and mode of entry of fungi into DC was responsible for Th polarization and patterns of susceptibility or resistance to infection [16,53,54]. Because IL-12 produced by DC1 appears to be critical to induction of a Th1 response, we included IL-12 in our cell line culture medium [39]. The use of a large pool of peptides to prime CD8+ and CD4+ T cell responses to individual antigens as a measure of precursor frequency to epitopes contained in the pool has been described and response to both known and novel peptides have been identified using this approach [37,38,55]. Use of overlapping peptides of 15-aa appears to be optimal for generating combined CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses [38]. Indeed, in confirmation, PBMC from a second donor primed in exactly the same fashion as donor RD0408 resulted in CD8+ Asp f16-specific T cell effectors reactive with three additional novel peptides (unpublished observations), so it would appear that our methods favour a Th1 response to Asp f16. The approach of priming to the entire pool of possible peptide epitopes offers the advantage of not requiring tailoring to the specific HLA type of the responder and of potentially generating responses to multiple peptide epitopes in a single line. Clinical trials are required to determine if adoptive transfer of donor-derived Asp f16-specific T cell lines specific for WSIDGAVVR are safe and if they can confer protection against Aspergillus infection in HPCT patients.

In conclusion, DC pulsed with a pool of pentadecapeptides from Asp f16 are capable of inducing a cytotoxic CD4+, HLA-DR-restricted, Aspergillus-specific Th1 type T cell response directed to a single peptide contained within the pool. Further characterization of this system is in progress to identify other immunogenic peptides from Asp f16 that might also be useful in clinical immunotherapy protocols to prime protective immune responses to prevent or treat Aspergillus infection.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Guenther Koehne (Rush University, Chicago, IL, USA) for helpful discussion on the preparation of the pentadecapeptides, Dr Tom Ellis (Blood Center of South-eastern Wisconsin) for allele level HLA typing of the apheresis donors used in these experiments and Candace Krepel (Medical College of Wisconsin) for use of her laboratory for the growing and preparation of Aspergillus conidia. This work was supported in part by a grant from the Medical College of Wisconsin Cancer Center.

References

- 1.Wiederhold NP, Lewis RE, Kontoyiannis DP. Invasive aspergillosis in patients with hematologic malignancies. Pharmacotherapy. 2003;23:1592–610. doi: 10.1592/phco.23.15.1592.31965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Denning DW. Invasive aspergillosis. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;26:781–803. doi: 10.1086/513943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marr KA, Patterson T, Denning D. Aspergillosis. Pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, and therapy. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2002;16:875–94. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5520(02)00035-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fukuda T, Boeckh M, Carter RA, et al. Risks and outcomes of invasive fungal infections in recipients of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplants after nonmyeloablative conditioning. Blood. 2003;102:827–33. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-02-0456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Denning DW. Diagnosis and management of invasive aspergillosis. Curr Clin Top Infect Dis. 1996;16:277–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mahfouz T, Anaissie E. Prevention of fungal infections in the immunocompromised host. Curr Opin Invest Drugs. 2003;4:974–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crameri R, Blaser K. Allergy and immunity to fungal infections and colonization. Eur Respir J. 2002;19:151–7. doi: 10.1183/09031936.02.00229102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ribaud P, Chastang C, Latge JP, et al. Survival and prognostic factors of invasive aspergillosis after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;28:322–30. doi: 10.1086/515116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grow WB, Moreb JS, Roque D, et al. Late onset of invasive Aspergillus infection in bone marrow transplant patients at a university hospital. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2002;29:15–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1703332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marr KA, Carter RA, Boeckh M, Martin P, Corey L. Invasive aspergillosis in allogeneic stem cell transplant recipients: changes in epidemiology and risk factors. Blood. 2002;100:4358–66. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-05-1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marr KA, Carter RA, Crippa F, Wald A, Corey L. Epidemiology and outcome of mould infections in hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:909–17. doi: 10.1086/339202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alangaden GJ, Wahiduzzaman M, Chandrasekar PH. Aspergillosis: the most common community-acquired pneumonia with Gram-negative bacilli as copathogens in stem cell transplant recipients with graft-versus-host disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;35:659–64. doi: 10.1086/342061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De La Rosa GR, Champlin RE, Kontoyiannis DP. Risk factors for the development of invasive fungal infections in allogeneic blood and marrow transplant recipients. Transpl Infect Dis. 2002;4:3–9. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3062.2002.00010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Keever-Taylor CA. Immune reconstitution following allogeneic transplantation. In: Soiffer RJ, editor. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Totowa: Humana Press, Inc.; 2001. pp. 201–36. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Romani L. The T cell response against fungal infections. Curr Opin Immunol. 1997;9:484–90. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(97)80099-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bozza S, Gaziano R, Lipford GB, et al. Vaccination of mice against invasive aspergillosis with recombinant Aspergillus proteins and CpG oligodeoxynucleotides as adjuvants. Microbes Infect. 2002;4:1281–90. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(02)00007-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hebart H, Bollinger C, Fisch P, et al. Analysis of T cell responses to Aspergillus fumigatus antigens in healthy individuals and patients with hematologic malignancies. Blood. 2002;100:4521–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-01-0265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cenci E, Mencacci A, Bacci A, Bistoni F, Kurup VP, Romani L. T cell vaccination in mice with invasive pulmonary aspergillosis. J Immunol. 2000;165:381–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.1.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bozza S, Perruccio K, Montagnoli C, et al. A dendritic cell vaccine against invasive aspergillosis in allogeneic hematopoietic transplantation. Blood. 2003;102:3807–14. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-03-0748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Netea MG, Warris A, Van der Meer JW, et al. Aspergillus fumigatus evades immune recognition during germination through loss of toll-like receptor-4-mediated signal transduction. J Infect Dis. 2003;188:320–6. doi: 10.1086/376456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ramadan G, Konings S, Kurup VP, Keever-Taylor CA. Generation of Aspergillus- and CMV-specific T cell responses using autologous fast DC. Cytotherapy. 2004;6:223–34. doi: 10.1080/14653240410006040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kurup VP, Kumar A. Immunodiagnosis of aspergillosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1991;4:439–56. doi: 10.1128/cmr.4.4.439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Latge JP. Aspergillus fumigatus and aspergillosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1999;12:310–50. doi: 10.1128/cmr.12.2.310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dhillon M. Current status of mold immunotherapy. Ann Allergy. 1991;66:385–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Banerjee B, Kurup VP. Molecular biology of Aspergillus allergens. Front Biosci. 2003;8:s128–39. doi: 10.2741/982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Crameri R, Blaser K. Cloning Aspergillus fumigatus allergens by the pJuFo filamentous phage display system. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 1996;110:41–5. doi: 10.1159/000237308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Crameri R. Recombinant Aspergillus fumigatus allergens: from the nucleotide sequences to clinical applications. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 1998;115:99–114. doi: 10.1159/000023889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kurup VP, Banerjee B, Hemmann S, Greenberger PA, Blaser K, Crameri R. Selected recombinant Aspergillus fumigatus allergens bind specifically to IgE in ABPA. Clin Exp Allergy. 2000;30:988–93. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.2000.00837.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kurup VP. Fungal allergens. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2003;3:416–23. doi: 10.1007/s11882-003-0078-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moser M, Crameri R, Menz G, et al. Cloning and expression of recombinant Aspergillus fumigatus allergen I/a (rAsp f I/a) with IgE binding and type I skin test activity. J Immunol. 1992;149:454–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kumar A, Reddy LV, Sochanik A, Kurup VP. Isolation and characterization of a recombinant heat shock protein of Aspergillus fumigatus. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1993;91:1024–30. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(93)90215-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mayer C, Hemmann S, Faith A, Blaser K, Crameri R. Cloning, production, characterization and IgE cross-reactivity of different manganese superoxide dismutases in individuals sensitized to Aspergillus fumigatus. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 1997;113:213–15. doi: 10.1159/000237550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mayer C, Appenzeller U, Seelbach H, et al. Humoral and cell-mediated autoimmune reactions to human acidic ribosomal P2 protein in individuals sensitized to Aspergillus fumigatus P2 protein. J Exp Med. 1999;189:1507–12. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.9.1507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rathore VB, Johnson B, Fink JN, Kelly KJ, Greenberger PA, Kurup VP. T cell proliferation and cytokine secretion to T cell epitopes of Asp f2 in ABPA patients. Clin Immunol. 2001;100:228–35. doi: 10.1006/clim.2001.5056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Banerjee B, Kurup VP, Greenberger PA, Johnson BD, Fink JN. Cloning and expression of Aspergillus fumigatus allergen Asp f16 mediating both humoral and cell-mediated immunity in allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA) Clin Exp Allergy. 2001;31:761–70. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.2001.01076.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kern F, Faulhaber N, Khatamzas E, et al. Measurement of anti-human cytomegalovirus T cell reactivity in transplant recipients and its potential clinical use: a mini-review. Intervirology. 1999;42:322–4. doi: 10.1159/000053967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Armengol E, Wiesmuller KH, Wienhold D, et al. Identification of T cell epitopes in the structural and non-structural proteins of classical swine fever virus. J Gen Virol. 2002;83:551–60. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-83-3-551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maecker HT, Dunn HS, Suni MA, et al. Use of overlapping peptide mixtures as antigens for cytokine flow cytometry. J Immunol Meth. 2001;255:27–40. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(01)00416-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Emtage PC, Clarke D, Gonzalo-Dagonzo R, Junghans RP. Generating potent Th1/Tc1 T cell adoptive immunotherapy doses using human IL-12. Harnessing the immunomodulatory potential of IL-12 without the in vivo-associated toxicity. J Immunother. 2003;26:97–106. doi: 10.1097/00002371-200303000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xu S, Koski GK, Faries M, et al. Rapid high efficiency sensitization of CD8+ T cells to tumor antigens by dendritic cells leads to enhanced functional avidity and direct tumor recognition through an IL-12-dependent mechanism. J Immunol. 2003;171:2251–61. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.5.2251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Koehne G, Smith KM, Ferguson TL, et al. Quantitation, selection, and functional characterization of Epstein–Barr virus-specific and alloreactive T cells detected by intracellular interferon-gamma production and growth of cytotoxic precursors. Blood. 2002;99:1730–40. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.5.1730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Balajee SA, Marr KA. Conidial viability assay for rapid susceptibility testing of Aspergillus species. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:2741–5. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.8.2741-2745.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Meshulam T, Levitz SM, Christin L, Diamond RD. A simplified new assay for assessment of fungal cell damage with the tetrazolium dye, (2,3)-bis-(2-methoxy-4-nitro-5-sulphenyl)-(2H)-tetrazolium-5-carboxanil ide (XTT) J Infect Dis. 1995;172:1153–6. doi: 10.1093/infdis/172.4.1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Singh H, Raghava GP. ProPred: prediction of HLA-DR binding sites. Bioinformatics. 2001;17:1236–7. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.12.1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Betts MR, Brenchley JM, Price DA, et al. Sensitive and viable identification of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells by a flow cytometric assay for degranulation. J Immunol Meth. 2003;281:65–78. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(03)00265-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wu CH, Yeh LS, Huang H, et al. The protein information resource. Nucl Acids Res. 2003;31:345–7. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Parker JM, Guo D, Hodges RS. New hydrophilicity scale derived from high-performance liquid chromatography peptide retention data: correlation of predicted surface residues with antigenicity and X-ray-derived accessible sites. Biochemistry. 1986;25:5425–32. doi: 10.1021/bi00367a013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Beno DW, Stover AG, Mathews HL. Growth inhibition of Candida albicans hyphae by CD8+ lymphocytes. J Immunol. 1995;154:5273–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Appay V, Zaunders JJ, Papagno L, et al. Characterization of CD4(+) CTLs ex vivo. J Immunol. 2002;168:5954–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.11.5954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Appay V, Dunbar PR, Callan M, et al. Memory CD8+ T cells vary in differentiation phenotype in different persistent virus infections. Nat Med. 2002;8:379–85. doi: 10.1038/nm0402-379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hamann D, Baars PA, Rep MH, et al. Phenotypic and functional separation of memory and effector human CD8+ T cells. J Exp Med. 1997;186:1407–18. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.9.1407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Svirshchevskaya EV, Alekseeva LG, Andronova TM, Kurup VP. Do T helpers 1 and 2 recognize different class II MHC molecules? Humoral and cellular immune responses to soluble allergen from Aspergillus fumigatus Asp f2. Clin Immunol. 2001;100:349–54. doi: 10.1006/clim.2001.5067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Grazziutti M, Przepiorka D, Rex JH, Braunschweig I, Vadhan-Raj S, Savary CA. Dendritic cell-mediated stimulation of the in vitro lymphocyte response to Aspergillus. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2001;27:647–52. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1702832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Claudia M, Bacci A, Silvia B, Gaziano R, Spreca A, Romani L. The interaction of fungi with dendritic cells: implications for Th immunity and vaccination. Curr Mol Med. 2002;2:507–24. doi: 10.2174/1566524023362203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Leen AM, Sili U, Savoldo B, et al. Fiber-modified adenoviruses generate sub-group cross-reactive, adenovirus-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes for therapeutic applications. Blood. 2004;103:1011–19. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-07-2449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]