Abstract

Tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α, a major proinflammatory cytokine, exerts its role on bone cells through two receptors (TNFR1 and TNFR2). TNFR1, but not TNFR2, is expressed by osteoblasts and its function in bone formation in vivo is not fully understood. We compared in vivo new bone formation in TNFR1-deficient (TNFR1–/–) mice and wild-type mice, using two models of bone formation: intramembranous ossification following tibial marrow ablation and endochondral ossification induced by bone morphogenetic protein (BMP)-2. Intramembranous osteogenesis in TNFR1–/– mice did not differ from the wild-type mice either in histomorphometric parameters or mRNA expression of bone-related markers and inflammatory cytokines. During endochondral osteogenesis, TNFR1–/– mice formed more cartilage (at post-implantation day 9), followed by more bone and bone marrow (at day 12). mRNAs for BMP-2, -4 and -7 were increased during the endochondral differentiation sequence in TNFR1–/– mice. The expression of receptor activator of NF-κB ligand (RANKL) and receptor activator of NF-κB (RANK), as assessed by quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), was also increased significantly during endochondral ossification in TNFR1–/– mice. In conclusion, signalling through the TNFR1 seems to be a negative regulator of new tissue formation during endochondral but not intramembranous osteogenesis in an adult organism. BMPs and RANKL and its receptor RANK may be involved in the change of local environment in the absence of TNFR1 signalling.

Keywords: bone, mouse, osteoinduction, receptor activator of NF-κB ligand (RANKL), tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNF)-α

Introduction

The close relationship between the bone and immune system is based not only on their anatomical proximity, but also on their cellular and molecular interactions [1]. Among numerous cytokines and colony stimulating factors, the members of the tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-related family of ligands and receptors have a pivotal role in both the immune system and bone [2,3].

The TNF family currently has 19 ligands and 29 receptors [4]. The first described member of the superfamily was TNF-α[5], which acts as an essential mediator of both innate and acquired immune responses and is important for the development of the immune system [6,7]. In addition, TNF-α plays an important role in the bone as a potent osteoresorptive cytokine, stimulating the differentiation and activity of osteoclasts [8,9] and inhibiting osteoblast differentiation [10].

TNF-α exerts its biological role through two cell surface receptors: TNF receptor 1 or p55 (TNFR1), and TNF receptor 2 or p75 (TNFR2) [4,11]. In the immune system, TNFR1 primarily mediates cytotoxicity and cytokine secretion, whereas TNFR2 is associated with lymphoproliferation and T cell activation [4,12]. In bone, both receptors are expressed by osteoclasts, whereas osteoblasts express only TNFR1 [13]. In vitro, signalling through TNFR1 inhibits preosteoblast differentiation [14]. In vivo, the absence of both receptors delays fracture repair [15,16]. As fracture repair involves both endochondral and intramembranous mechanisms of bone formation, our aim was to investigate the role of TNF receptors separately in endochondral and intramembranous osteoneogenesis. Also, to distinguish the separate effects of the two TNF receptors, we studied mice deficient in TNFR1, which has a predominant expression in bone-forming cells [13]. For that purpose, two in vivo models of adult bone regeneration were used: induction of endochondral bone formation by recombinant human (rh) bone morphogenetic protein (BMP)-2 [17] and stimulation of intramembranous osteogenesis by mechanical bone marrow ablation [18].

Materials and methods

Mice

Mice homozygous for the TNFR1 gene knockout (–/–) were generated by gene targeting [19]. The original strain of TNFR1–/– mice was on a C3H genetic background; the mice were subsequently back-crossed through more than 10 generations onto a pure C57BL/6 J background. C57BL/6 J mice were used as wild-type control. Female mice (12 weeks of age) were used in all experiments. The Ethics Committee of the Zagreb University School of Medicine approved all animal protocols.

Bone marrow ablation

Bilateral tibial bone marrow ablation was performed under general anaesthesia [18]. A longitudinal incision was made to expose the tibial condyles and a 1 mm hole was made at the intercondylar area with a surgical drill. A 23-gauge needle was inserted into the marrow cavity and marrow was aspirated by vacuum suction and flushed with sterile saline. Mice were euthanized before the ablation (day 0) or 6, 8 and 10 days post-ablation. Tibiae from one side were processed for histology and from the other for Northern blot and reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) analyses.

Bone induction by rhBMP-2

Recombinant human (rh) BMP-2 was a kind gift from the Genetics Institute (Cambridge, MA, USA). One µg of rhBMP-2 was mixed with 50 µl of blood from syngeneic mice and allowed to form a firm clot in a 1·5-ml tube [17,20]. After setting at room temperature for 1 h, the clot was implanted subcutaneously in both pectoral regions of anaesthetized mice. The implants were dissected out 6, 9 and 12 days after implantation. Implants from one side were processed for histology and from the other for Northern blot and RT-PCR analyses.

Histological analysis

The specimens for histological analysis were weighed, decalcified in 14% EDTA, and embedded in paraffin [20]. Implants were cut serially into 6-µm thick sections with a standard microtome and stained with Goldner's trichrome stain. The volume of the newly formed tissue in the rhBMP-2 implants was measured on serial sections (every 10th section throughout the thickness of the whole specimen) by counting points of a Merck ocular grid over bone, bone marrow space, cartilage, mesenchyme and implanted blood clot [20]. Mean total weight of newly formed tissues was calculated by multiplying the mean relative volume (determined by histomorphometry) of a tissue type with the mean wet weight of the implants for a specific time-point [20]. For histomorphometric analyses of tibiae, 6 µm frontal sections through the intercondylar eminence were used and the measurements were made as described previously [18]. Histomorphometry was performed under light microscope (20× magnification) by a blinded observer on three representative sections from each animal (five animals) and their mean was taken for further analyses.

RNA preparation

RhBMP-2 implants and tibiae were immersed in liquid nitrogen and then homogenized by a hard tissue homogenizer. Total RNA was extracted using a commercial kit (Tri-Reagent; Molecular Research Center Cincinnati, OH, USA). Each RNA sample was prepared from a pool of three bones or five implants.

Northern blot analysis

For each sample, 10 µg total RNA were fractioned on a 1·5% agarose gel with 1·1 mmol/l formaldehyde, and transferred by capillary pressure to a nylon membrane. The hybridization with radioactive probes for mouse osteopontin, bone sialoprotein, osteocalcin and collagen α1(I) was performed as described previously [20]. The autoradiographs were analysed by laser densitometry. The densitometry readings for specific probes were normalized for variations in gel loading by dividing the optical density (OD) readings by 18S rRNA OD readings, after correction for background. RNA samples from two independent experiments gave similar patterns of gene expression in repeated blots.

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification

For each sample, 15 µg of total RNA were converted to cDNA by reverse transcriptase according to the previously published protocol [20]. To verify that the amplifications were in the linear range of each PCR analysis, we performed PCR amplifications of up to 36 cycles for each probe and sample. β-Actin was amplified at 27 cycles; bone morphogenetic protein (BMP)-4, BMP-7, interleukin (IL)-1α at 30 cycles; and BMP-2, TNF-α, at 33 cycles. The amplified products were run in a 1·5% agarose gel, stained with ethidium bromide and photographed under ultraviolet (UV) light. Images were scanned and optical density of the bands was determined using a digital image processing and analysis software package (Scion Image; Scion Corporation, Frederick, MD, USA). The densitometry readouts for specific primers were normalized by the β-actin readout, after correction for background.

Specific amplimer sets for murine BMP-2, -4 and -7 were a kind gift from the Genetics Institute, Cambridge, MA, USA. Other amplimer sets [interleukin (IL)-1α, TNF-α and β-actin] were designed from published cDNA sequences [20]. For each mouse strain and time-point, reverse transcription (RT) was performed on RNA isolated from two independent experiments, and PCR was performed in duplicate for each cDNA, to ensure the reproducibility of the assay.

Quantitative PCR

Quantitative PCR was performed using the ABI Prism 7000 Sequence Detection system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA), following the published protocol [21]. The reaction products were detected by measuring the binding of SYBR Green I to DNA using the SYBR Green PCR Master Mix, as recommended by the manufacturer (Applied Biosystems).

The primers for b-actin, receptor activator of NF-kB (RANK), receptor activator of NF-kB ligand (RANKL) and osteoprotegerin (OPG) were designed using Primer Express software (Applied Biosystems): b-actin, product size 243 bp (antisense 5′-CGGATGTCAACGTCACACTT-3′, sense 5′-TGCGTGACATCAAAGAGAAG-3′); RANK, 211 bp (antisense 5′-ACAACGGTCCCCTGAGGACT-3′, sense 5′-GACACTGAGGAGACCACCCAA-3′); RANKL, 144 bp (antisense 5′-AAGCATCGGAATACCTCTCCC-3′;, sense 5′-AGCCCTCTCTCTTGAGCCCT-3′;); and OPG, 142 bp (antisense 5′-CTGCTCTGTGGTGAGGTTCG-3′, sense 5′-AGAGCAAACCTTCCAGCTGC-3′). Relative quantification of the PCR products was performed as described previously [21].

Statistics

The histomorphometric measurements and the results of quantitative PCR were expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (s.e.m.). The histomorphometric data were analysed by two-tailed anova and Student–Newman–Keuls post-hoc test, while the PCR results and the masses of the implants were compared using Student's t-test with Bonferroni's correction. The alpha level was set at 0·05.

Results

TNFR1 signalling does not affect osteogenic regeneration after bone marrow ablation

Mechanical bone marrow ablation was used as a model of stimulation of intramembranous ossification. In both TNFR1–/– and wild-type mice, bone regeneration provoked by marrow ablation followed the well-known cellular sequence [16,20,21]: filling up of the marrow cavity by a blood clot and the appearance of first bone trabeculae at day 6; creation of a dense network of newly formed trabeculae and resorption of the blood clot at day 8; and intense trabecular resorption and repopulation of bone marrow at day 10.

Trabecular bone volume increased following the ablation, from 3·8 ± 1·5% pre-ablation to 5·1 ± 3·2% at day 6 and 25·7 ± 3·4% at day 8 post-ablation in TNFR1–/– mice, comparable with 3·9 ± 0·8% pre-ablation, 6·4 ± 2·6% at day 6, and 22·0 ± 5·9% at day 8 post-ablation in wild-type mice (P > 0·05). By day 10, trabecular bone volume decreased due to the intense bone resorption in both groups of mice (15·9 ± 2·3% in TNFR1–/– and 16·1 ± 5·9% in wild-type mice). Trabecular separation had reciprocal dynamics in TNFR1–/– mice (578·2 ± 105·7 µm pre-ablation, 312·6 ± 157·1 µm at day 6, 64·7 ± 15·1 µm at day 8 and 93·8 ± 41·8 µm at day 10 post-ablation) as well as in wild-type mice (502·7 ± 99·1 µm pre-ablation, 380·8 ± 274·3 µm at day 6, 86·2 ± 27·3 µm at day 8 and 135·2 ± 63·3 µm at day 10 post-ablation; P > 0·05).

TNFR1–/– and control mice also had comparable expressions of bone-related markers (collagen α1(I), osteopontin, bone sialoprotein and osteocalcin, and BMP-2, -4 and -7), as well as inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α and IL-1α) during osteogenic regeneration after marrow ablation (data not shown).

TNFR1 signalling is involved in endochondral ossification in adult mice

To assess extraskeletal endochondral ossification in TNFR1–/– mice, we used stimulation by rhBMP-2 in a blood clot as a carrier. The cascade of endochondral osteogenesis in wild-type mice showed a typical differentiation pattern [17]: mesenchymal cell proliferation was followed by cartilage differentiation and hypertrophy (day 6); resorption of the blood clot and mesenchyme, differentiation of osteoblasts and formation of bone (day 9); and remodelling of the ossicle and population of marrow spaces by haematopoietic bone marrow (day 12) (Fig. 1). The total weight of the implants did not differ between TNFR1–/– mice and wild-type mice on day 6 (1·94 ± 0·49 g versus 2·01 ± 0·51 g, respectively) but was significantly greater in TNFR1–/– animals on day 9 (2·49 ± 0·57 g versus 1·29 ± 0·24 g, P < 0·05) and day 12 (2·16 ± 0·12 g versus 1·57 ± 0·45 g, P < 0·05). As we performed morphometrical analyses on serial sections through the newly formed ossicle, we were able to make conclusions on the absolute weight of the newly formed tissue. At all time-points, TNFR1–/– mice had a significantly greater weight of the newly formed tissues than the wild-type mice: more mesenchyme at day 6, more cartilage at day 9 and more bone and bone marrow at day 12 post-implantation (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

(a) Weight of newly formed tissues in the ossicles of wild-type mice (C57BL/6) and mice homozygous for the tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α receptor 1 knock-out (TNFR1–/–) 6, 9 and 12 days post-implantation of 1 µg of recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2. Weight of individual tissues was calculated from their relative volumes (%) on serial sections of implanted ossicles and the total wet weight of ossicles cleansed of surrounding tissue. Open bars: C57BL/6 mice, closed bars: TNFR1–/– mice. The values are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (s.e.m.) (n = 5 animals per group). aP < 0·05 versus wild-type for the same time-point (anova and Student–Newman–Keuls post-hoc test). (b) Photomicrographs of the newly induced tissue 6, 9 and 12 days after subcutaneous rhBMP-2 implantation (magnification × 200, Goldner's trichrome stain). At day 6, proliferation of mesenchymal cells and some islands of cartilage (arrow) are visible in both wild-type (C57BL/6) and TNFR1–/– knock-out (TNFR1–/–) mice. Islands of cartilage are larger and mesechymal cells more abundant in TNFR1–/– implants. At day 9, cartilage is calcified and slowly resorbed to make way for the bone; the cartilage cells are more compact in TNFR1–/– implants. At day 12 the ossicle is fully formed, with bony trabeculae and bone marrow.

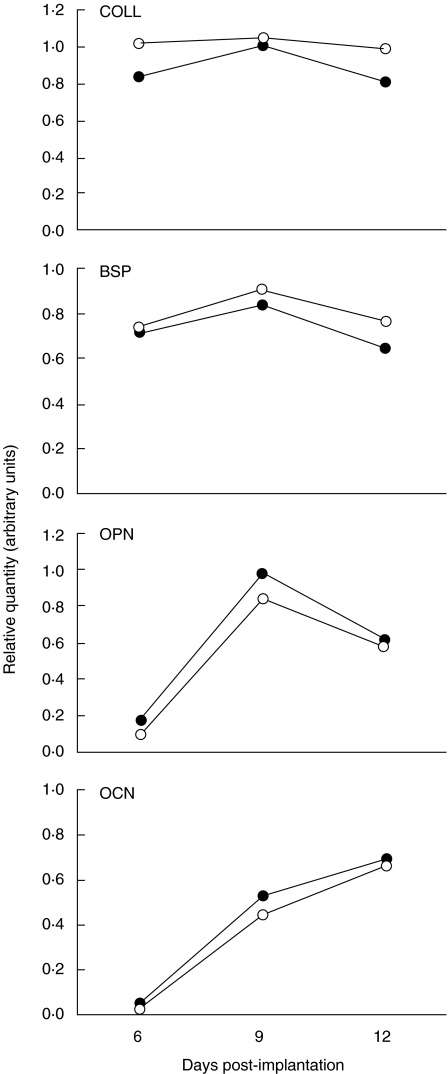

Although we observed greater absolute weights of newly formed bone, the mRNA expression of bone-related markers (collagen, osteopontin, bone sialoprotein and osteocalcin), as assessed by Northern blot analysis, was almost identical in TNFR1–/– and wild-type mice (Fig. 2). As mRNA expression was always calculated relative to a housekeeping gene expression, this finding indicated that the activity/differentiation stage of the induced cells did not change, but their greater number contributed to the increased weight of the ossicles in TNFR1–/– mice. In both TNFR1–/– and wild-type mice, the expression of bone-related markers followed the differentiation of the ossicle: osteocalcin increased over time, corresponding to the differentiation of new bone [22], whereas abundant expression of collagen α1(I) at all time-points indicated metabolically active cells. The activity of bone sialoprotein and osteopontin peaked at day 9, when cartilage formation dominated the osteogenic sequence [23,24].

Fig. 2.

Pattern of gene expression of bone sialoprotein (BSP), osteocalcin (OCN), collagen α1(I) (COLL) and osteopontin (OPN), as assessed by Northern blot, 6, 9 and 12 days post-implantation of 1 µg of recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 in wild-type mice (C57BL/6) and mice homozygous for the tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α receptor 1 knock-out (TNFR1–/–). The values represent the ratio of optical density (OD) readings of a particular gene product and respective 18S rRNA reading. RNA samples were prepared from a pool of five implants; representative blot from two experiments. Open circles: C57BL/6 mice; closed circles: TNFR1–/– mice.

TNFR1 signalling is involved in the expression of BMPs and RANKL/RANK during endochondral ossification in vivo

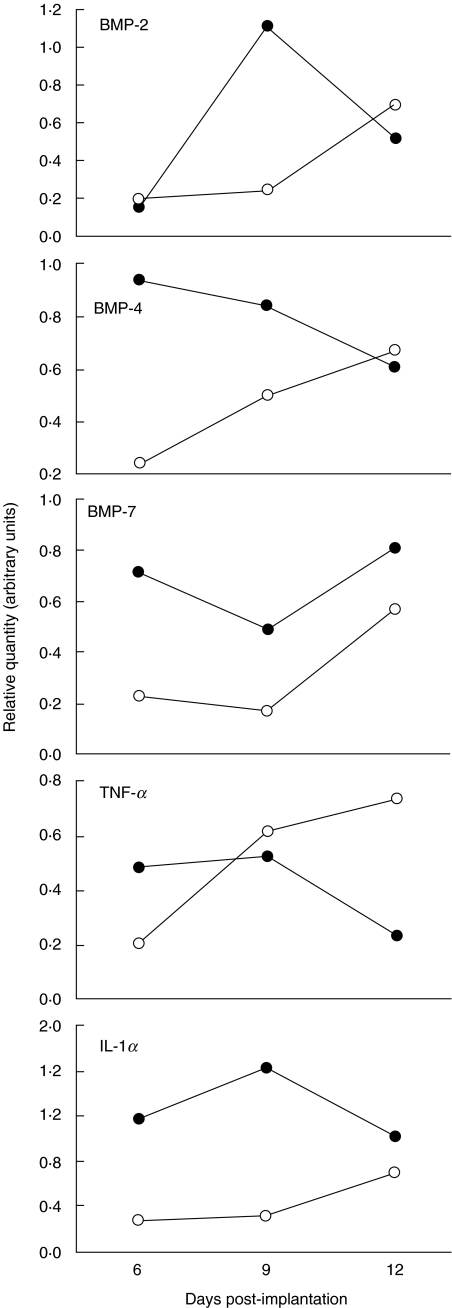

To evaluate cytokines or growth factors possibly altered by the lack of TNFR1 signalling during endochondral osteogenesis, we first assessed the activity of genes for BMP-2, -4 and -7, as potent stimulators of ectopic bone formation [25]. In semiquantitative RT-PCR, the temporal pattern of their expression in TNFR1–/– mice differed from that in control mice. Each BMP had a unique expression pattern (Fig. 3) but their collective expression in TNFR1–/– mice was higher at all time-points.

Fig. 3.

Pattern of gene expression for bone morphogenetic proteins (BMP)-2, -4 and -7 and cytokines tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α and interleukin (IL)-1α by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction 6, 9 and 12 days post-implantation of 1 µg of recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 in wild-type mice (C57BL/6) and mice homozygous for the tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α receptor 1 knock-out (TNFR1–/–). The values represent the ratio of optical density (OD) reading of a particular gene product and the respective β-actin OD reading. RNA samples were prepared from a pool of five implants; representative run from two independent experiments. Open circles: C57BL/6 mice; closed circles: TNFR1–/– mice.

As the immune reaction plays a critical role in starting and maintaining the osteogenic sequence [18,26,27], we also used RT-PCR to assess the expression of TNF-α and IL-1α (Fig. 3). TNF-α expression in TNFR1–/– mice diminished during the osteoinductive sequence, in contrast to the increasing expression in control mice. The level of IL-1α expression in TNFR1–/– mice was constantly higher than in the wild-type mice.

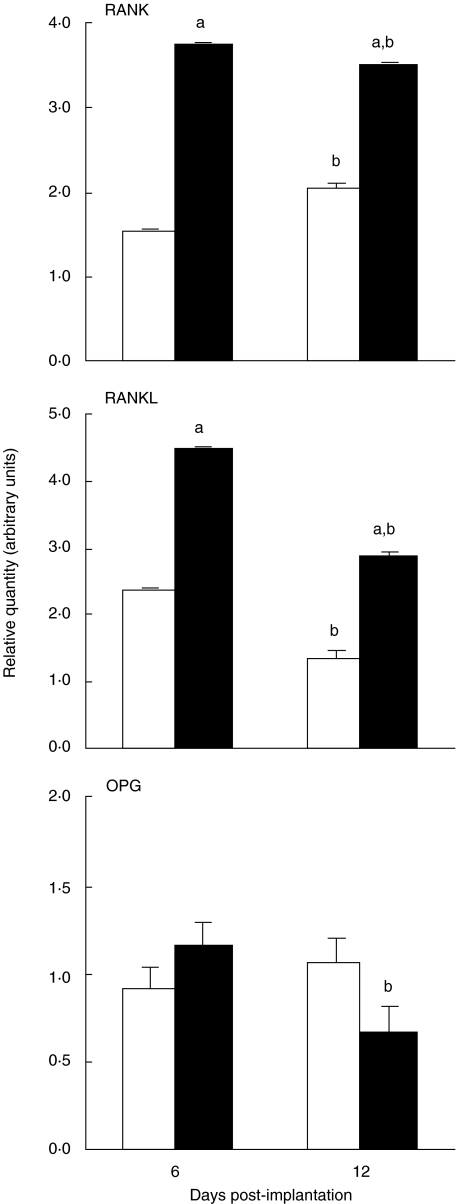

After we observed altered mRNA expression patterns for IL-1α and TNF-α during endochondral osteogenesis, we assessed the expression of RANKL by quantitative PCR, a well-known downstream effector of both TNF-α and IL-1α on bone cells [28], and its two receptors: RANK and OPG (Fig. 4). TNFR1–/– mice had a significantly higher expression of RANKL and RANK than the wild-type mice both at the beginning (day 6) and at the end (day 12) of the osteogenic sequence. In both TNFR1–/– and wild-type mice, RANKL was especially increased at day 6, during the intense mesenchyme proliferation. In contrast to RANK and RANKL, the expression of the OPG in the two groups of mice was comparable at day 6, but decreased significantly at day 12 in TNFR1–/– mice compared with day 6 (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Gene expression for RANK, RANKL and OPG by reverse transcription and quantitative polymerase chain reaction 6 and 12 days post-implantation of 1 µg of recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 in wild-type mice (C57BL/6) and mice homozygous for the tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α receptor 1 knock-out (TNFR1–/–). The values represent mean ± standard error of the mean (s.e.m.) of relative quantities of RANK, RANKL or OPG normalized for β-actin cDNA. RNA samples were prepared from a pool of five implants; the data shown are from a representative of two independent experiments. Open bars: C57BL/6 mice; closed bars: TNFR1–/– mice. aP < 0·05 versus wild-type for the same time point; bP < 0·05 versus same group, day 6 (Student's t-test with Bonferroni's correction).

Discussion

Our study showed that the absence of TNFR1 signalling promoted endochondral osteogenesis but did not affect intramembranous bone formation in an adult organism in vivo. This indicates that endochondral and intramembranous osteogenesis in an adult organism are regulated by different molecular mechanisms and suggests that TNFR1 plays an important role in the restriction of endochondral ossification. In the model of intramembranous osteogenesis, Gerstenfeld et al. [15,16] showed that osteogenic reaction to marrow ablation was delayed in mice with a double TNFR1/R2 knock-out. As we show in this study that this type of osteogenesis in an adult organism is not affected by the TNFR1 gene deletion, it seems that TNFR2 may be more important in the regulation of intramembranous osteogenesis.

Our study also confirmed the complexity of the physiological effects of TNF signalling in vivo and the importance of the local environment: in the bone marrow, intramembranous ossification can be induced by stimulating endosteal osteoblasts [16] and fracture healing involves both endochondral and intramembranous ossification [16]; and in subcutaneous tissue, BMPs initiate the recruitment and differentiation of local mesenchymal progenitors [29].

The site of action of TNFR1 signalling during postnatal endochondral ossification seems to be at the level of cell proliferation and not differentiation because greater weight of newly formed cartilage and bone in TNFR1–/– mice was paralleled by mostly unchanged patterns of expression of bone-associated markers [bone sialoprotein (BSP), osteocalcin (OCN), collagen and osteopontin (OPN)]. This is not surprising, as it has been shown that the maturation process of the osteoblast lineage cells in vitro is not altered in the absence of TNFR1 [30]. Our findings of unchanged mRNA expression of bone-related markers coupled with greater weight of ossicles indicates that the effect of TNFR1 was on the early stages of bone induction and not on later tissue differentiation.

Endochondral osteogenesis induced by BMPs has an important inflammatory component, which is crucial for the normal cellular cascade of mesenchymal progenitor recruitment, proliferation and differentiation into cartilage [31]. Macrophages accumulate next to the implanted BMP carrier early after implantation in vivo, and BMPs can induce directed migration of monocytes at femtomolar concentrations in vitro[29], suggesting that a key step in bone induction is the chemotaxis of monocytes in response to BMPs. BMPs also stimulate the expression of transforming growth factor (TGF)-β in monocytes [29], which in turn stimulates bone formation and the additional expression of BMPs themselves [32]. A similar inflammatory reaction has been described in a fracture repair model in the mouse, which involves both endochondral and intramembranous ossification and where induction of TNF-α and IL-1 immediately after fracture is paralleled by a large accumulation of immune cells at the fracture site [33]. In previous studies, we have shown in several in vivo models that alterations in the immune system affect primarily the initial cellular steps in the endochondral osteoinductive sequence [1,18,20]. Removal of either B lymphocytes [18] or T lymphocytes [1] from the site of osteoinduction promotes the proliferation of mesenchymal progenitors and their subsequent differentiation. We also showed that the effects of the immune system may be related to the apoptotic restriction of both immune response and osteogenic sequence because the absence of the Fas/Fas ligand apoptotic pathway results in an increased trabecular bone mass in long bones, as well as a more vigorous osteogenic response both in the model of marrow ablation [21] and BMP-2 induced endochondral osteogenesis [20]. The stimulatory effect of TNFR1 on angiogenesis [34] could also contribute to the increased cellular proliferation at the site of BMP-2 implantation because angiogenesis is a key step in endochondral bone formation [35].

In an in vivo situation there are probably very complex interactions between immunological and bone cells and determining the contributions of individual factors is difficult. The source of TNF-α at the sites of osteogenesis in such an environment is multicellular, including macrophages attracted by chemotaxis, lymphocytes and activated fibroblasts in the early phases of the osteoinduction sequence, as well as chondroblasts and osteoblasts at later stages [15,16,31]. In turn, the secretion of TNF-α induces the release of other cytokines, which act in an autocrine or paracrine manner on the site of new bone induction [36]. For this reason, we did not analyse the expression of individual cytokines but rather followed the composite profile of cytokines and bone related-markers expressed during endochondral bone induction. Mice lacking TNFR1 had a unique pattern of cytokine gene expression, with prominent alterations in the expression of genes for BMPs and the RANKL/RANK cytokine system. Increased endochondral ossification in mice lacking TNFR1 was associated with collectively increased expression of BMP-2, -4 and -7 during endochondral development, indicating that TNFR1 signalling may be the regulator of BMP action. It has been shown previously that exogenous TNF-α can inhibit BMP-induced osteogenesis in vivo[37], as well as BMP-induced alkaline phosphatase in osteoblastic cells in vitro[38]. Our study implicates that the TNFR1-mediated restriction of endochondral osteogenesis is achieved, at least in part, through the down-regulation of BMPs as major osteoinductive agents.

Previous studies of osteogenesis during fracture repair confirmed the regulatory role of the RANKL/RANK/OPG cytokine system, especially in the resorption of cartilage and remodelling of newly formed bone [15,33,39]. Also, RANKL/RANK system and TNF can affect each other's expression in a positive feedback manner during osteoclastogenesis [40–43]. We found at least a twofold greater expression of RANK and RANKL, coupled with an unchanged OPG expression, 6 days after BMP stimulation, when the induced tissue consisted mainly of proliferating mesenchymal cells with small islands of newly formed cartilage. These findings suggest that RANK/RANKL interactions are important not only for osteoclastic stimulation [40–43] but during the initial stages of endochondral ossification. A possible target of RANK/RANKL may be angiogenesis, as it has been shown that RANKL stimulates angiogenesis [44]. Also, RANK is expressed on and RANKL secreted by many cells present during the inflammatory stage of BMP-induced endochondral osteogenesis, including B and T lymphocytes, fibroblasts and endothelial cells [45,46].

To summarize, our study showed that TNFR1-mediated signalling could be an important restrictor of postnatal endochondral bone formation but not of intramembranous osteogenesis. This restriction seems to be mediated by a complex down-regulation of BMPs and the RANKL/RANK cytokine systems during early cell proliferation and differentiation. The immunological milieu at the site of endochondral osteoinduction and initial cellular interactions thus emerge as crucial parts of the cellular differentiation cascade under the regulation of TNF. The interaction between the bone and immune system at such an early stage of endochondral osteogenesis in the adult organism opens a complex research area, as well as possibilities for therapeutic interventions in bone surgery and repair, as well as bone-affecting inflammatory diseases.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by US–Croatian Joint Research Fund grant no. JF199 and the Ministry of Science and Technology of the Republic of Croatia grant no. 108181 (Ana Marušić). We are indebted to the Genetics Institute, Boston, MA, USA for their generous gift of rhBMP-2 and primers for BMPs. We thank Mrs Katerina Zrinski-Petrović for her technical assistance.

References

- 1.Grčević D, Katavić V, Lukić IK, Kovačić N, Lorenzo JA, Marušić A. Cellular and molecular interactions between immune system and bone. Croat Med J. 2001;42:384–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lorenzo J. Interactions between immune and bone cells: new insights with many remaining questions. J Clin Invest. 2000;106:749–52. doi: 10.1172/JCI11089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hofbauer LC, Khosla S, Dunstan CR, Lacey DL, Boyle WJ, Riggs BL. The roles of osteoprotegerin and osteoprotegerin ligand in the paracrine regulation of bone resorption. J Bone Miner Res. 2000;15:2–12. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2000.15.1.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aggarwal BB. Signalling pathways of the TNF superfamily: a double-edged sword. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:745–56. doi: 10.1038/nri1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carswell EA, Old LJ, Kassel RL, Green S, Fiore N, Williamson B. An endotoxin-induced serum factor that causes necrosis of tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1975;72:3666–70. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.9.3666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mackay F, Kalled SL. TNF ligands and receptors in autoimmunity: an update. Curr Opin Immunol. 2002;14:783–90. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(02)00407-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bazzoni F, Beutler B. The tumor necrosis factor ligand and receptor families. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:1717–25. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199606273342607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Azuma Y, Kaji K, Katogi R, Takeshita S, Kudo A. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha induces differentiation of and bone resorption by osteoclasts. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:4858–64. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.7.4858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abu-Amer Y, Erdmann J, Alexopoulou L, Kollias G, Ross FP, Teitelbaum SL. Tumor necrosis factor receptors types 1 and 2 differentially regulate osteoclastogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:27307–10. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003886200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gilbert L, He X, Farmer P, et al. Inhibition of osteoblast differentiation by tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Endocrinology. 2000;141:3956–64. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.11.7739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ashkenazi A. Targeting death and decoy receptors of the tumour-necrosis factor superfamily. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:420–30. doi: 10.1038/nrc821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xiang J, Gordon JR. Genetic engineering of a recombinant fusion protein possessing an antitumor antibody fragment and a TNF-α moiety. In: Koerholz D, Kiess W, editors. Cytokines and colony stimulating factors: methods and protocols. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press Inc.; 2003. pp. 201–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bu R, Borysenko CW, Li Y, Cao L, Sabokbar A, Blair HC. Expression and function of TNF-family proteins and receptors in human osteoblasts. Bone. 2003;33:760–70. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2003.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abbas S, Zhang YH, Clohisy JC, Abu-Amer Y. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibits pre-osteoblast differentiation through its type-1 receptor. Cytokine. 2003;22:33–41. doi: 10.1016/s1043-4666(03)00106-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gerstenfeld LC, Cho TJ, Kon T, et al. Impaired fracture healing in the absence of TNF-alpha signalling: the role of TNF-alpha in endochondral cartilage resorption. J Bone Miner Res. 2003;18:1584–92. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2003.18.9.1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gerstenfeld LC, Cho TJ, Kon T, et al. Impaired intramembranous bone formation during bone repair in the absence of tumor necrosis factor-alpha signalling. Cells Tissues Organs. 2001;169:285–94. doi: 10.1159/000047893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marušić A, Grčević D, Katavić V. New bone induction by bone matrix and recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 in the mouse. Croat Med J. 1996;37:237–44. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marušić A, Grčević D, Katavić V, et al. Role of B lymphocytes in new bone formation. Lab Invest. 2000;80:1761–74. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3780186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pfeffer K, Matsuyama T, Kundig TM, et al. Mice deficient for the 55 kd tumor necrosis factor receptor are resistant to endotoxic shock, yet succumb to L. monocytogenes infection. Cell. 1993;73:457–67. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90134-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Katavić V, Grčević D, Lukić IK, et al. Non-functional Fas ligand increases the formation of cartilage early in the endochondral bone induction by rhBMP-2. Life Sci. 2003;74:13–28. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2003.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Katavić V, Lukić IK, Kovačić N, Grčević D, Lorenzo JA, Marušić A. Increased bone mass is a part of the generalized lymphoproliferative disorder phenotype in the mouse. J Immunol. 2003;170:1540–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.3.1540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Power MJ, Fottrell PF. Osteocalcin: diagnostic methods and clinical applications. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 1991;28:287–335. doi: 10.3109/10408369109106867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sommer B, Bickel M, Hofstetter W, et al. Expression of matrix proteins during the development of mineralized tissues. Bone. 1996;19:371–80. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(96)00218-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nakase T, Sugimoto M, Sato M, et al. Switch of osteonectin and osteopontin mRNA expression in the process of cartilage-to-bone transition during fracture repair. Acta Histochem. 1998;100:287–95. doi: 10.1016/S0065-1281(98)80015-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cheng H, Jiang W, Phillips FM, et al. Osteogenic activity of the fourteen types of human bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs) J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85–A:1544–52. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200308000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marušić A, Dikić I, Vukičević S, Marušić M. New bone induction by demineralized bone matrix in immunosuppressed rats. Experientia. 1992;48:783–5. doi: 10.1007/BF02124303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marušić A, Katavić V, Grčević D, Lukić IK. Genetic variability of new bone induction in mice. Bone. 1999;25:25–32. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(99)00095-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Takahashi N, Udagawa N, Takami M, Suda T. Cells of bone. Osteoclast generation. In: Bilezikian J, Raisz L, Rodan G, editors. Principles of bone biology. 2nd. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 2002. pp. 109–26. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cunningham NS, Paralkar V, Reddi AH. Osteogenin and recombinant bone morphogenetic protein 2B are chemotactic for human monocytes and stimulate transforming growth factor beta 1 mRNA expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:11740–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.24.11740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gilbert L, Brantley A, Rubin J, Nanes MS. 24th Annual Meeting of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research, San Antonio, Texas. Washington, DC: American Society for Bone and Mineral Research; 2002. The P55 TNF receptor mediates TNF inhibition of osteoblast differentiation. [CD ROM]. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Urist M. The first three decades of the bone morphogenetic protein research. Osteologie. 1995;4:207–23. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wozney JM, Rosen V. Bone morphogenetic protein and bone morphogenetic protein gene family in bone formation and repair. Clin Orthop. 1998;346:26–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kon T, Cho TJ, Aizawa T, et al. Expression of osteoprotegerin, receptor activator of NF-kappaB ligand (osteoprotegerin ligand) and related proinflammatory cytokines during fracture healing. J Bone Miner Res. 2001;16:1004–14. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2001.16.6.1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mori R, Kondo T, Oheshima T, Ishida Y, Mukaida N. Accelerated wound healing in tumor necrosis factor receptor p55-deficient mice with reduced leukocyte infiltration. FASEB J. 2002;16:963–74. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0776com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Harper J, Klagsbrun M. Cartilage to bone − angiogenesis leads the way. Nat Med. 1999;5:617–8. doi: 10.1038/9460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nanes MS. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha: molecular and cellular mechanisms in skeletal pathology. Gene. 2003;321:1–15. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(03)00841-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yoshikawa H, Hashimoto J, Masuhara K, Takaoka K, Ono K. Inhibition by tumor necrosis factor of induction of ectopic bone formation by osteosarcoma-derived bone-inducing substance. Bone. 1988;9:391–6. doi: 10.1016/8756-3282(88)90121-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nakase T, Takaoka K, Masuhara K, Shimizu K, Yoshikawa H, Ochi T. Interleukin-1 beta enhances and tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibits bone morphogenetic protein-2-induced alkaline phosphatase activity in MC3T3–E1 osteoblastic cells. Bone. 1997;21:17–21. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(97)00038-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li P, Schwarz EM, O'Keefe RJ, Ma L, Boyce BF, Xing L. RANK signalling is not required for TNFalpha-mediated increase in CD11 (hi) osteoclast precursors but is essential for mature osteoclast formation in TNFalpha-mediated inflammatory arthritis. J Bone Miner Res. 2004;19:207–13. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.0301233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hofbauer LC, Lacey DL, Dunstan CR, Spelsberg TC, Riggs BL, Khosla S. Interleukin-1beta and tumor necrosis factor-alpha, but not interleukin-6, stimulate osteoprotegerin ligand gene expression in human osteoblastic cells. Bone. 1999;25:255–9. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(99)00162-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Komine M, Kukita A, Kukita T, Ogata Y, Hotokebuchi T, Kohashi O. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha cooperates with receptor activator of nuclear factor kappaB ligand in generation of osteoclasts in stromal cell-depleted rat bone marrow cell culture. Bone. 2001;28:474–83. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(01)00420-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zou W, Hakim I, Tschoep K, Enders S, Bar-Shavit Z. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha mediates RANK ligand stimulation of osteoclast differentiation by an autocrine mechanism. J Cell Biochem. 2001;83:70–83. doi: 10.1002/jcb.1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang YH, Heulsmann A, Tondravi MM, Mukherjee A, Abu-Amer Y. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF) stimulates RANKL-induced osteoclastogenesis via coupling of TNF type 1 receptor and RANK signalling pathways. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:563–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008198200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Min J-K, Kim Y-M, Kim Y-M, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor up-regulates expression of receptor activator NF-κB (RANK) in endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:39548–57. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300539200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Manabe N, Kawaguchi H, Chikuda H, et al. Connection between B lymphocyte and osteoclast differentiation pathways. J Immunol. 2001;167:2625–31. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.5.2625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Anderson HC, Hodges PT, Aguilera XM, Missana L, Moylan PE. Bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) localization in developing human and rat growth plate, metaphysis, epiphysis, and articular cartilage. J Histochem Cytochem. 2000;48:1493–502. doi: 10.1177/002215540004801106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]