Abstract

The regulatory role of chemokines and chemokine receptors on specific leucocyte recruitment into periodontal diseased tissue is poorly characterized. We observed that leucocytes infiltrating inflamed gingival tissue expressed marked levels of CX3CR1. In periodontal diseased tissue, the expression of fractalkine and CX3CR1 mRNA was detected by reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and further, fractalkine was distributed mainly on endothelial cells, as shown by immunohistochemistry. Moreover, we can detect CX3CR1-expressing cells infiltrated in periodontal diseased tissue by immunohistochemical staining. Furthermore, fractalkine production by human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) was up-regulated by pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), including Porphyromonas gingivalis lipopolysaccharide (LPS). Thus, these findings suggested that CX3CR1 and the corresponding chemokine, fractalkine may have an important regulatory role on specific leucocyte migration into inflamed periodontal tissue.

Keywords: CX3CR1, fractalkine, periodontal disease

Introduction

Periodontal disease is characterized as chronic inflammation associated with Gram-negative bacteria in the oral cavity [1,2]. Infiltration of various types of leucocytes is involved in the gingival tissues of periodontal disease, and leucocyte accumulation has been shown to play a crucial role in the pathogenesis of periodontal disease [3]. Chemokines are small-secreted proteins involved in the control of leucocyte traffic and inflammation. Based on a conserved cysteine motif forming disulphide bonds, four families, CXC, CC, C and CX3C, have been identified. The effects on leucocytes are mediated by seven-transmembrane domain G protein-coupled receptors. There are 18 known functional chemokine receptors that bind multiple chemokines in a subclass-restricted manner. By binding to their receptors, chemokines induce cytoskeletal reorganization and integrin activation followed by migration into tissues [4]. Expression of several chemokines and their receptors has been found in periodontal diseased tissue [5–8], suggesting the possible contribution of these chemokines to leucocyte accumulation and inflammatory responses.

Fractalkine is a unique, membrane-bound chemokine, with a transmembrane domain and the chemokine domain on top of a long mucin-like stalk. Fractalkine shares high homology with the CC family of chemokines, but presents three amino acids between the first two-cysteine residues (the CX3C structural motif). The molecule can exist in two forms, membrane-anchored or shed soluble glycoprotein, after extracellular proteolysis at a membrane-proximal dibasic cleavage site, similar to cleavage of syndecans [9,10]. Fractalkine was described initially as being expressed on interleukin (IL)-1 and tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-activated endothelial cells [9,10] and having a wide mRNA distribution in human [9] and murine tissues [10]. CX3CR1 is a specific receptor for fractalkine, and CX3CR1 is expressed on Th1-type cells [11], natural killer (NK) cells [12] and macrophages [13]. It is suggested that fractalkine/CX3CR1 interaction will be related with the pathogenesis of some inflammatory diseases such as psoriasis [11] and rheumatoid arthritis [13]. However, the expression of fractalkine and CX3CR1 is not certain in periodontal diseased tissue.

In the present study, we used reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) analysis and immunohistochemistry to detect fractalkine expression and CX3CR1-expressing cells infiltration in periodontal tissues. Moreover, we examined fractalkine production by endothelial cells stimulated with pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) including Porphyromonas gingivalis lipopolysaccharide (LPS) using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).

Materials and methods

Collection of samples

Collection of samples was performed as described previously [8] with slight modification. All subjects were submitted to anamnesis and to clinical, periodontal and radiographic examination. Prior to the beginning of the study, all subjects received supragingival prophylaxis to remove gross calculus and allow proving access. All teeth were scored for probing depth and clinical attachment level, at six sites per tooth by a single calibrated investigator. The patients were categorized according to the classification of the American Academy of Periodontology into healthy control or chronic periodontitis. The patients were systemically healthy with no evidence of known systemic modifiers of periodontal disease (types I and II diabetes mellitus, osteoporosis and medications known influence periodontal tissues). Exclusion criteria included those patients who had taken systemic antibiotic, anti-inflammatory, hormonal or other assisted drug therapy in the 6 months prior to the study, or who had received previous periodontal therapy in the last 2 years. Smokers were not specifically excluded. Chronic periodontal patients had moderate to advanced periodontal disease (at least one tooth per sextant with probing depth >4 mm, attachment loss >3 mm, extensive radiographic bone loss and sulcular bleeding on probing). After basic periodontal therapy (oral hygiene and removing supragingival plaque and calculus), biopsies of gingival tissue (including junctional epithelium, gingival crevicular epithelium and connective gingival tissue) were obtained during surgical therapy of the sites that exhibited persistent bleeding on probing and that showed no improvement in clinical condition 3–4 weeks after the basic periodontal therapy. Samples of gingival tissues were obtained from 17 chronic periodontitis patients (four males and 13 females, aged 49–82 years old) and six healthy control subjects (three males and three females, aged 26–40 years). We used six chronic periodontitis samples and three healthy control samples for RT-PCR and 11 chronic periodontitis samples and three control samples for immunohistochemical staining. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects participating in this study. The study was performed with the approval and compliance of the Tokushima University Ethical Committee.

Cells and cell culture

Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) was obtained from Iwaki (Chiba, Japan) and maintained in endothelial cells growth medium [10 ng/ml human epidermal growth factor, 1·0 µg/ml hydrocortisone, 50 µg/ml gentamicin, 50 µg/ml amphotericin B, 12 µg/ml bovine brain extract and 2% fetal calf serum (FCS)], as recommended by the manufacturer. HUVEC was stimulated with Escherichia coli 0111; B4 LPS (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA), P. gingivalis w83 LPS, Staphylococcus aureus lipoteichoic acid (LTA) (Sigma) or Streptococcus mutans LTA (Sigma) for 4 h (RT-PCR) or 24 h [enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)]. P. gingivalis w83 LPS was purified by phenol–water extraction. In some experiments, HUVEC was stimulated by TNF-α (peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ, USA) with or without LPS or LTA.

RT-PCR analysis

Total RNA was prepared from gingival biopsies or HUVEC using Isogen (Gibco/BRL, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) and first-strand cDNAs were synthesized using random 9 primer (TaKaRa Shuzo, Kyoto, Japan) and reverse transcriptase (TaKaRa). The resulting first-strand DNA was amplified in a final volume of 20 µl containing 10 pmol of each primer and 1 U of Taq polymerase (TaKaRa Shuzo). The primers used were: +5′-CCGAAGGAGCAATGGGTCAA-3′ and −5′-CA GGTTGGTGGGGAGCAG-3′ for fractalkine; +5′-TTGAG TACGATGATTTGGCTG-3′ and −5′-GGCTTTGGCTTTCT TGTGG-3′ for CX3CR1; +5′-TGAAGGTCGGAGTCAACG GATTTGGT-3′ and −5′-CATGTGGGCCATGAGGTCCACC AC-3′ for GAPDH. Amplification conditions were denaturation at 94°C for 1 min, annealing at 60°C for 1 min and extension at 72°C for 1 min for 35 cycles. Amplification products (5 µl each) were subjected to electrophoresis on 1·5% agarose gel and stained with ethidium bromide.

Immunohistochemistry

Gingival biopsies were immediately embedded in O.T.C. compound (Miles Laboratories Inc., Elkhart, IN, USA) and quenched and stored in liquid nitrogen. The specimens were cut at 6 µm using a cryostat (SFS, Bright instrumental Company, Huntingdon, UK) and collected on poly l-lysine-coated slides. Fractalkine, CX3CR1 and Factor XIII were analysed with specific antibodies: antihuman fractalkine rabbit polyclonal antibody (Torrey Pines Biolabs, Inc., Houston, TX, USA), antihuman CX3CR1 rabbit polyclonal antibody (Torrey Pines Biolabs), antihuman Factor XIII mouse MoAb (clone 089; Dako, Kyoto, Japan) and we used isotype matched control MoAb (Dako) or non-immune rabbit serum antibody (Dako) as the negative control. The sections were reacted with specific antibodies overnight at 4°C. After washing with phosphate buffered saline (PBS), the sections were incubated with biotinylated antimouse and rabbit immunoglobulin (Universal Antibody; Dako) for 20 min at room temperature and washed with PBS to remove unreacted antibodies. The sections were then treated with peroxidase-conjugated streptavidin (Dako) for 10 min, and washed and reacted with DAB (3,3-diamino-benzidine tetrahydrochrolide; Dako) in the presence of 3% H2O2 to develop colour. The sections were counterstained with haematoxylin and mounted with glycerol.

Cytokine assay

Fractalkine concentration in the culture supernatant was measured by ELISA using Duoset (R&D systems, Minneapolis, MI, USA); the assay was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. The data were determined by using a standard curve prepared for each assay.

Statistical analysis

Statistical significance was analysed by Student's t-test. P-values <0·05 were considered significant.

Results

Fractalkine and CX3CR1 mRNA expression in inflamed gingival tissue and normal gingival tissue

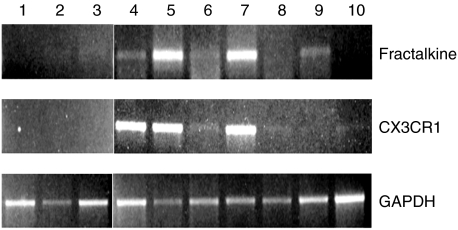

We first examined fractalkine and CX3CR1 mRNA expression by whole gingival tissue from periodontal diseased tissues and normal gingival tissues. Fractalkine mRNA was expressed by five of seven periodontal diseased tissues, although fractalkine mRNA expression was very weak in two of five positive samples. In contrast, no fractalkine mRNA expression was detected of three normal gingival tissues. CX3CR1 mRNA was detected in five of seven samples in periodontal diseased tissues, although CX3CR1 mRNA expression in two samples was very weak. No CX3CR1 mRNA expression was detected in normal gingival tissues (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

RT-PCR analysis of expression of fractalkine and CX3CR1 in human gingiva. Total RNA was prepared from gingival biopsies from three normal donors and seven periodontal disease patients. RT-PCR analysis was carried out for fractalkine and GAPDH as described in Materials and methods. 1–3, gingival biopsies from normal donors; 4–10, gingival biopsies from periodontal diseased patients.

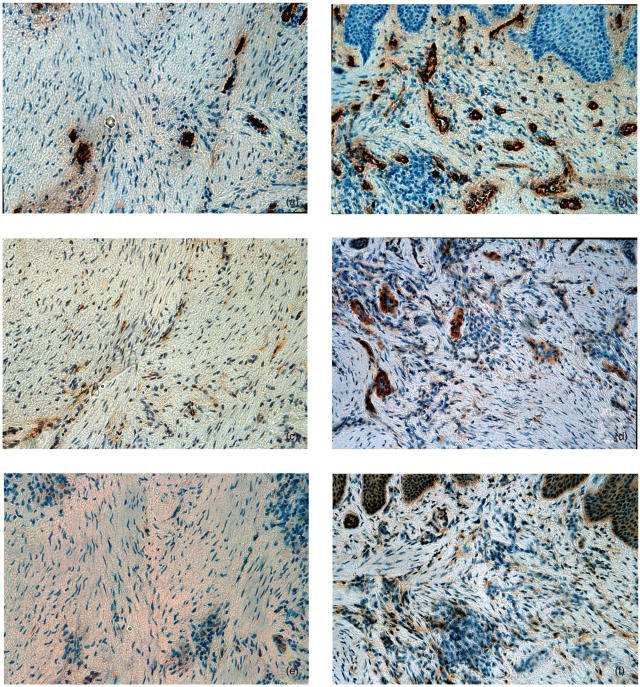

Augmented expression of fractalkine and accumulation of CX3CR1-expressing cells in human periodontal diseased tissue

To examine fractalkine expression and infiltration of CX3CR1-expressing cells in periodontal diseased tissue, we carried out immunohistochemical staining of fractalkine and CX3CR1 in normal gingival tissues (n = 3) and inflamed gingival tissues (n = 11). The representative results are shown in Fig. 2. In normal gingival tissue, gingival endothelial cells were stained by anti-Factor XIII antibody (Fig. 2a) but hardly stained by antifractalkine antibody (Fig. 2c). Fractalkine expression by endothelial cells was very weak in all sections of normal gingival tissues that we used for immunohistochemical staining. Furthermore, CX3CR1-expressing cells were very few in normal gingival tissue (Fig. 2e). On the other hand, we observed strong staining of endothelial cells by antifractalkine antibody in inflamed gingival tissues from periodontal diseased patients. Some gingival crevicular epithelial cells were also stained by antifractalkine antibody (Fig. 2d). Fractalkine expression by endothelial cells was detected in all samples of periodontal diseased tissues and the fractalkine expression by endothelial cells in periodontal diseased sections was much stronger than that in normal tissue sections. In addition, many CX3CR1-expressing cells were infiltrated in inflamed gingival tissue (Fig. 2f). CD3-positive T cells were infiltrated in the same area infiltrated by CX3CR1-expressing cells (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

Immunohistochemical analysis of human periodontal tissues. (a) Normal gingiva stained with anti-Factor XIII MoAb; (b) inflamed gingiva stained with anti-Factor XIII MoAb; (c) normal gingiva stained with antifractalkine antibody; (d) inflamed gingiva stained with antifractalkine antibody; (e) normal gingiva stained with anti-CX3CR1 antibody; (f) inflamed gingiva stained with anti-CX3CR1 antibody (original magnification ×200).

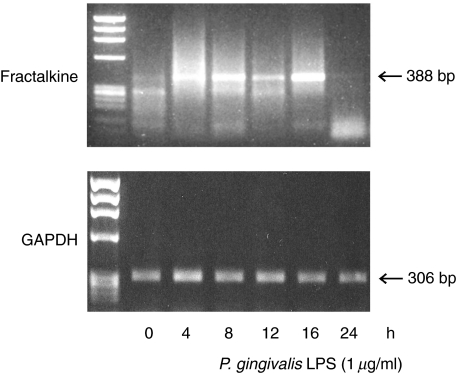

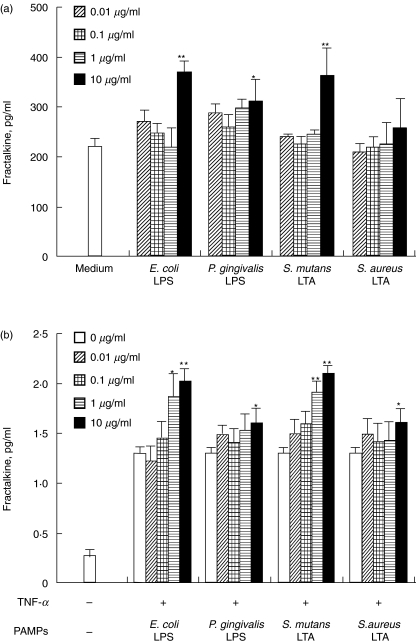

Effects of LPS and LTA on HUVEC fractalkine production

Fractalkine staining of endothelial cells in periodontal diseased tissue indicate that these endothelial cells were a possible source of fractalkine production. As shown in Fig. 3, fractalkine mRNA expression was enhanced by P. gingivalis LPS. Expression was enhanced at 4 h stimulation, peaked at 8 h stimulation and returned to the basic level at 24 h stimulation. Figure 4a shows that E. coli LPS, P. gingivalis LPS and S. mutans LTA significantly induced fractalkine production by HUVEC. It is reported that TNF-α induced fractalkine by HUVEC [9]. Next, we stimulated HUVEC by TNF-α with or without LPS or LTA. Figure 4b shows that E. coli LPS, P. gingivalis LPS, S. mutans LTA and S. aureus LTA enhanced the fractalkine production by TNF-α-induced HUVEC.

Fig. 3.

Fractalkine mRNA expression in endothelial cells by P. gingivalis LPS. HUVEC was incubated in the presence of P. gingivalis LPS (1 µg/ml) for 0–24 h. Total RNA was extracted using Isogen reagent. Complementary DNA was amplified using primers for human fractalkine. As a control, PCR was also performed for GAPDH.

Fig. 4.

LPS and LTA induce fractalkine production by HUVEC. (a) HUVEC was incubated with E. coli LPS (5 ng/ml−5 µg/ml), P. gingivalis LPS (10 ng/ml−10 µg/ml), S. mutans LTA (10 ng/ml−10 µg/ml) or S. aureus LTA (10 ng/ml−10 µg/ml) for 24 h. (b) HUVEC was incubated by TNF-α (10 ng/ml) with or without E. coli LPS (5 ng/ml−5 µg/ml), P. gingivalis LPS (10 ng/ml−10 µg/ml), S. mutans LTA (10 ng/ml−10 µg/ml) or S. aureus LTA (10 ng/ml−10 µg/ml) for 24 h. The HUVEC supernatants were collected and the production of fractalkine was measured by ELISA, as described in Materials and methods. Data are presented as the mean of three independent experiments. Error bars exhibit the s.d. of the values. *P < 0·05, **P < 0·01 significantly different from medium alone (a) or the supernatant exposed to TNF-α (10 ng/ml) alone (b).

Discussion

Local inflammatory immune reactions of the host response to periodontal pathogen seem to be decisive to protect the host against infection, but may lead to pathological alterations in host tissues. Selective migration of different cell types to gingival tissues is apparently related to the immunopathogenesis of periodontal disease. We focused on fractalkine in chemokines because in some diseases it is reported to be involved in pathological damage [11,13], and it is unknown whether or not fractalkine is expressed in periodontal tissues. Thus, we focused on fractalkine in many chemokines. We used RT-PCR and immunohistochemistry to detect fractalkine and its receptor CX3CR1 expression in periodontal tissues. Moreover, we examined whether PAMPs including P. gingivalis LPS can induce fractalkine production by endothelial cells because endothelial cells are extremely important for the control of cell migration into periodontal diseased tissues.

It is reported that CX3CR1 is expressed mainly by CD45RO+ cells, and almost exclusively by activated HLA-DR T lymphocytes [14]. This indicates that CX3CR1 plays a role in accumulation of memory and activated T cells. It is reported that most CD4+ T cells in periodontal diseased tissue are CD45RO+ T cells [15], and that CD4+ CD45RO+ memory-type T cells express CCR6 [16]. Moreover, we have reported previously that abundant CCR6+ T cells infiltrated into periodontal diseased tissues [6]. These results suggest that both CCR6/MIP-3α (CCR6 ligand) interaction and CX3CR1/fractalkine interaction may control the migration of memory T cells into periodontal diseased tissue.

Recently, Fraticelli et al. demonstrated that CX3CR1 is expressed preferentially in Th1 compared with Th2, and Th1 but not Th2 respond to fractalkine [11]. It is suggested that the interaction of fractalkine and CX3CR1 may contribute to the accumulation of Th1-type cells in rheumatoid arthritis synovium and psoriasis [11,13]. A number of studies have attempted to reveal the Th1/Th2 profile in periodontal disease [15,17,18]. However, it is not certain what controls the Th1/Th2 balance. This study suggests that fractalkine/CX3CR1 interaction may be related to the migration of Th1 into inflamed gingival tissue and partially control the Th1/Th2 balance in periodontal tissues.

NK cells are infiltrated into periodontal diseased tissue and are suggested to play an important role in the destruction of periodontal diseased tissue [19]. It is reported that NK cells express CX3CR1 [12] and adhere to the fractalkine [20]. Thus, CX3CR1 and fractalkine interaction may control the infiltration of NK cells into periodontal diseased tissue. Moreover, macrophages also express CX3CR1 [13]. It is known that macrophages are involved in the pathogenesis of periodontal disease. We found that fractalkine is expressed mainly by endothelial cells in periodontal diseased tissue. These results suggest that fractalkine produced by endothelial cells in periodontal diseased tissue may control the migration of several types of inflammatory cells, including Th1, NK cells and macrophages.

It is reported that one type of cell expresses some types of chemokine receptors. For example, Th1 cells express CCR5, CXCR3 and CX3CR1 [11,21] and NK cells express CCR1, CCR4, CCR7, CXCR3, CXCR4 and CX3CR1 [12,22]. Several chemokines are expressed in periodontal diseased tissues. For example, MCP-1 (CCR1 ligand), MIP-1α (CCR1 and CCR5 ligand), RANTES (CCR1 and CCR5 ligand) and IP-10 (CXCR3 ligand) are expressed in periodontal diseased tissues [5,7,8]. These previous reports and our results suggest that more than one chemokine controls one type of cell, meaning that the chemokine system in periodontal diseased tissue will be extremely complex. Further investigation will be necessary for clearing the chemokine system in periodontal tissue.

It is reported that fractalkine expression on HUVEC is induced by inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1 or TNF-α[9], and membrane-bound fractalkine has been shown to be involved in the adhesion of leucocytes to endothelial cells in in vitro studies [23,24]. In this study we revealed that endothelial cells in periodontal diseased tissue expressed fractalkine, and PAMPs such as LPS and LTA induced the production of fractalkine. Moreover, we have revealed that LPS and LTA enhanced HUVEC fractalkine production induced by TNF-α. Therefore, we suggest that inflammatory cytokines and bacterial factors induce fractalkine by endothelial cells in periodontal diseased tissue and these results mean that both proinflammatory cytokine and bacteria may control lymphocytes transmigration from the bloodstream to inflamed gingival tissue.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that leucocytes in periodontal diseased tissue express CX3CR1 and the ligand chemokine fractalkine is expressed strongly on endothelial cells in periodontal diseased tissues; also the expression of fractalkine is up-regulated by PAMPs, including P. gingivalis LPS. Thus, the fractalkine/CX3CR1 system may play an important role in the infiltration of leucocytes into periodontal diseased tissue, and this might contribute to the progression of periodontal disease.

References

- 1.Dzink JL, Tanner AC, Haffajee AD, Socransky SS. Gram negative species associated with active destructive periodontal lesions. J Clin Periodontol. 1985;12:648–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1985.tb00936.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Socransky SS, Haffajee AD, Cugini MA, Smith C, Kent RL., Jr Microbial complexes in subgingival plaque. J Clin Periodontol. 1998;25:134–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1998.tb02419.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seymour GJ, Gemmell E, Reinhardt RA, Eastcott J, Taubman MA. Immunopathogenesis of chronic inflammatory periodontal disease: cellular and molecular mechanisms. J Periodont Res. 1993;28:478–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1993.tb02108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yoshie O, Imai T, Nomiyama H. Chemokines in immunity. Adv Immunol. 2001;78:57–110. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(01)78002-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gemmell E, Carter CL, Seymour GJ. Chemokines in human periodontal disease tissues. Clin Exp Immunol. 2001;125:134–41. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2001.01511.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hosokawa Y, Nakanishi T, Yamaguchi D, et al. Macrophage inflammatory protein 3alpha-CC chemokine receptor 6 interactions play an important role in CD4+ T-cell accumulation in periodontal diseased tissue. Clin Exp Immunol. 2002;128:548–54. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2002.01865.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kabashima H, Yoneda M, Nagata K, Hirofuji T, Maeda K. The presence of chemokine (MCP-1, MIP-1alpha, MIP-1beta, IP-10, RANTES)-positive cells and chemokine receptor (CCR5, CXCR3)-positive cells in inflamed human gingival tissues. Cytokine. 2002;20:70–7. doi: 10.1006/cyto.2002.1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garlet GP, Martins W, Jr, Ferreira BR, Milanezi CM, Silva JS. Patterns of chemokines and chemokine receptors expression in different forms of human periodontal disease. J Periodont Res. 2003;38:210–7. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0765.2003.02012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bazan JF, Bacon KB, Hardiman G, et al. A new class of membrane-bound chemokine with a CX3C motif. Nature. 1997;385:640–4. doi: 10.1038/385640a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pan Y, Lloyd C, Zhou H, et al. Neurotactin, a membrane-anchored chemokine upregulated in brain inflammation. Nature. 1997;387:611–7. doi: 10.1038/42491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fraticelli P, Sironi M, Bianchi G, et al. Fractalkine (CX3CL1) as an amplification circuit of polarized Th1 responses. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:1173–81. doi: 10.1172/JCI11517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Inngjerdingen M, Damaj B, Maghazachi AA. Expression and regulation of chemokine receptors in human natural killer cells. Blood. 2001;97:367–75. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.2.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blaschke S, Koziolek M, Schwarz A, et al. Proinflammatory role of fractalkine (CX3CL1) in rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2003;30:1918–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Foussat A, Coulomb-L’Hermine A, Gosling J, et al. Fractalkine receptor expression by T lymphocyte subpopulations and in vivo production of fractalkine in human. Eur J Immunol. 2000;30:87–97. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200001)30:1<87::AID-IMMU87>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Taubman MA, Kawai T. Involvement of T-lymphocytes in periodontal disease and in direct and indirect induction of bone resorption. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 2001;12:125–35. doi: 10.1177/10454411010120020301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liao F, Rabin RL, Smith CS, Sharma G, Nutman TB, Farber JM. CC-chemokine receptor is expressed on diverse memory subsets of T cells and determine responsiveness to macrophage inflammatory protein 3 alpha. J Immunol. 1999;162:186–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Takeichi O, Haber J, Kawai T, Smith DJ, Moro I, Taubman MA. Cytokine profiles of T-lymphocytes from gingival tissues with pathological pocketing. J Dent Res. 2000;79:1548–55. doi: 10.1177/00220345000790080401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fujihashi K, Yamamoto M, Hiroi T, Bamberg TV, McGhee JR, Kiyono H. Selected Th1 and Th2 cytokine mRNA expression by CD4(+) T cells isolated from inflamed human gingival tissues. Clin Exp Immun. 1996;103:422–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1996.tb08297.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fujita S, Takahashi H, Okabe H, Ozaki Y, Hara Y, Kato I. Distribution of natural killer cells in periodontal diseases: an immunohistochemical study. J Periodontol. 1992;63:686–9. doi: 10.1902/jop.1992.63.8.686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yoneda O, Imai T, Goda S, et al. Fractalkine-mediated endothelial cell injury by NK cells. J Immunol. 2000;164:4055–62. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.8.4055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sallusto F, Mackay CR, Lanzavecchia A. The role of chemokine receptor in primary, effector, and memory immune responses. Annu Rev Immunol. 2000;18:593–620. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meghazachi AA. G-protein-coupled receptors in natural killer cells. J Leukoc Biol. 2003;74:16–24. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0103019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fong AM, Robinson LA, Steeber DA, et al. Fractalkine and CX3CR1 mediate a novel mechanism of leukocyte capture, firm adhesion, and activation under physiologic flow. J Exp Med. 1998;188:1413–9. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.8.1413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goda S, Imai T, Yoshie O, et al. CX3C-chemokine, fractalkine-enhanced adhesion of THP-1 cells to endothelial cells through integrin-dependent and -independent mechanisms. J Immunol. 2000;164:4313–20. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.8.4313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]