Abstract

Because of the paucity of plasma HIV RNA viral load (VL) tests in resource-poor settings, the CD4+ T cell count is often used as the sole laboratory marker to evaluate the effectiveness of antiretroviral therapy (ART) in HIV-infected patients. In untreated patients, the level of activated T cells is positively correlated with VL and represents a prognostic marker of HIV infection. However, little is known about its value to predict early drug failure, taking into account the relatively high non-specific immune activation background observed in many resource-limited tropical countries. We assessed the use of immune activation markers (expression of CD38 and/or human leucocyte antigen-DR on CD8+ lymphocytes) to predict virological response to ART in a cohort of HIV-1 infected patients in Abidjan, Côte d'Ivoire. Correlations between VL, absolute CD4+ T cell counts and immune activation levels were examined in 111 HIV patient samples at baseline and after 6 and 12 months of therapy. The percentage of CD38+ CD8+ T cells appeared to be the best correlate of VL. In contrast, changes in CD4+ T cell counts provided a poor correlate of virological response to ART. Unfortunately, CD38+ CD8+ percentages lacked specificity for the determination of early virological drug failure and did not appear to be reliable surrogates of RNA viral load. CD38+ CD8+ T cell percentages may, rather, provide a sensitive estimate of the overall immune recovery, and be a useful extra laboratory parameter to CD4 counts that would contribute to improve the clinical management of HIV-infected people when VL testing facilities are lacking.

Keywords: antiretroviral therapy, HIV-1, immune activation, resource-poor countries, surrogate markers

Introduction

Treatment with antiretroviral drugs is becoming accessible to many HIV-infected people in resource-poor countries. However, the cost of standard laboratory tests required to monitor the effectiveness of antiretroviral therapy (ART) is still prohibitive for many patients and national programmes. In the industrialized world, regular HIV RNA viral load and CD4+ T cell count determinations are considered standard practice to monitor patients on ART. Early reductions in viral load in response to initiation of treatment are associated with a delay of disease progression and death [1–5]. CD4 cell count determination, which is used as a criterion to initiate therapy and to assess immunological response to treatment, improves the prognostic value of plasma viral load (VL levels) [6–8]. However, determination of viral load and absolute CD4 counts are expensive and require highly trained personnel and sophisticated laboratory infrastructure. Very few laboratories in developing countries, even at the central level, can afford viral load and CD4 count testing or both, which are currently more expensive than a month of lifesaving treatment in some African countries [9]. In this regard, the World Health Organization (WHO) has classified testing for absolute CD4 count as a desirable test and viral load determination as an optional test [10]. Thus, to improve HIV clinical care in developing countries, alternative biological markers that are simple, cheap and affordable to measure are needed. The importance of cellular immune activation as a surrogate indicator of virus replication has been shown [11]. The possibility of using immune activation level as an affordable substitute for the expensive viral load testing during treatment in resource-poor settings has also been suggested [12]. Lymphocyte surface antigens such as CD38 and human leucocyte antigen-DR (HLA-DR), a major histocompatibility complex class II antigen, are expressed or re-expressed on primed cells upon activation in HIV-infected people [13]. The number of CD8 lymphocytes expressing CD38 or HLA-DR at their surface has been shown to be a good predictor of disease progression in HIV-infected individuals [14–16]. In the absence of VL testing facilities, measurement of activated CD8 lymphocyte levels could therefore complement and improve the prognostic value of the absolute CD4 count in monitoring ART. Determination of both absolute CD4 counts and levels of activated CD8 lymphocytes on the same blood sample, using the same technology (flow cytometry) could contribute to a considerable reduction of the costs related to monitoring ART. However, monitoring ART with T cell activation markers should be sufficiently reliable and specific in order to consider this parameter as an alternative for viral load in HIV-infected African patients who generally display a high degree of CD8 T cell activation. In this study, we assessed the capacity of pre- and post-treatment immune activation levels to predict treatment outcome using RNA quantitative viral loads as our gold standard to measure virological response to ART in a cohort of HIV-1 infected patients in Abidjan, Côte d'Ivoire.

Materials and method

The UNAIDS-DAI (UNAIDS drug access initiative) began in Côte d'Ivoire in 1998, aimed to provide ART and other AIDS-related therapies at reduced cost to people infected with HIV. The Centre for Disease Control (CDC)-supported RETRO-CI laboratory provided all laboratory screening and monitoring. In this initiative, patients were monitored with a blood draw at each clinic visit scheduled at baseline, 1 month after initiation of therapy and every 3 months thereafter. Patients were considered to have received a highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) regimen if they received a combination of two nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) and a non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI) or protease inhibitor(s) (PIs), and dual therapy if they received two NRTIs only. For the present study, we reviewed all adults, previously ART-naive, HIV-1 (not dually)-infected with no observed opportunistic infection at the study entry and who initiated ART as part of the initiative between August 1998 and July 2002. We selected all (111) patients who had virological and immunological parameters available at baseline and at 6 and 12 months after the initiation of ART. We defined ‘good virological responders’ as patients who had maintained viral load below the detection limit of the assay (<200 copies/ml) between 6 and 12 months of therapy. We defined ‘poor virological responders’ as patients who had detectable viral loads (>200 copies/ml) at both 6 and 12 months. For each group, changes in CD4+ T cell counts, immune activation at baseline, 6 months and 12 months were analysed. ‘Good’ and ‘poor’ responders defined in this manner were used as reference groups. Patients who could not match the criteria of reference responders were classified as ‘intermediate responders’. Threshold values for CD4+, CD8+ CD38+ and CD8+ HLA-DR+ lymphocyte levels that could discriminate between ‘good’ and ‘poor’ responses to ART were derived from cut-off values determined from statistical analysis conducted in the reference groups. The prognostic capacity of these threshold values to detect viral drug failure (i.e. detectable viral load at months 6 or 12 or both) was tested on the entire cohort of 111 patients (i.e. both reference and intermediate responders).

This study received approval from the CDC Institutional Review Board and the ethical committee of the Ministry of Health of Côte d'Ivoire.

Laboratory testing

Blood samples were collected into Vacutainer CPT tubes (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA, USA) from all patients enrolled in the UNAIDS-DAI. Within 4 h of blood collection, plasma was separated from cells by centrifugation at 200 g, aliquoted and stored at −70°C. HIV antibody status was determined using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)-based parallel testing algorithm [17]. HIV type-specific serodiagnosis was performed using a combination of monospecific ELISAs as described previously [18]. HIV-1 RNA viral load in plasma was quantified by Amplicor HIV-1 Monitor (version 1·5) (Roche Diagnostic Systems, Branchburg, NJ, USA) that has a detection limit of 200 RNA copies/ml. Absolute white blood cell counts were determined from haematological measurements on a Coulter haematology analyser (Coulter, Miami, FL, USA). CD4+ T cell percentages were determined by three-colour flow cytometric measurements using FACScan (Becton Dickinson) on fresh peripheral whole blood within 4 h of collection. Aliquots of cells were stained with commercially available monoclonal antibodies. The Tritest kit and multiset software (Becton Dickinson) were used for analysis. Relative counts of CD4+ T cells were determined in EDTA-treated peripheral blood by a direct immunofluorescence method using a combination of anti-CD3 peridin chlorophyll protein (PerCP), anti-CD4 fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) and anti-CD8 phycoerythrin (PE). Absolute CD4 counts were calculated by multiplication of the percentages of CD4 cell by absolute numbers of lymphocytes. The expression of CD38 and HLA-DR on CD8 cells was determined using two combinations of monoclonal antibodies: (a) anti-CD3-PerCP/anti CD8-FITC/anti-HLA-DR-PE and (b) anti-CD8PerCP/anti-HLA-DR-FITC/anti-CD38-PE. For the determination of CD38+ CD8+ T cells, only CD8bright positive cells were gated to exclude the natural killer (NK) cells, which are usually CD8dim positive.

Statistical analysis

Undetectable viral loads were assigned a value of 100 RNA copies/ml (average of maximum and minimum possible undetectable values). CD4+ T cells and CD8+ T cell subpopulations were analysed as absolute count or percentages of lymphocytes and as changes from baseline values (delta values). The Kolgomorov–Smirnov test was applied to test the normal distribution of the variables in the entire cohort (n = 111). Non-parametric tests were used for statistical analyses. Differences between groups were tested for statistical significance using the Mann–Whitney U-test (reference good and poor responders) or the Wilcoxon signed-ranks tests for paired data (time-paired data in the entire group). Univariate correlations between the different variables in the entire group were examined with Spearman's rank order correlation tests. The use of activation markers to classify patients into reference groups of good and poor responders was assessed using the χ2 test. For each virological and immunological parameter, sensitivities, specificities, positive and negative predictive values in defining response to the treatment in the entire cohort were determined (e.g. the sensitivity of having a high level of activated cells in identifying patient with detectable viral load at months 6 or 12 or both). The level of significance alpha was set at 0·05. The statistical analyses were performed with the program spss version 11·0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Characteristics of the study population

Of the 111 study patients, 52 (46%) were female and 59 (53%) were male. None had active tuberculosis comorbidity at study entry. Sixteen were categorized as reference ‘good responders’ and 20 as reference ‘poor responders’. Median and interquartile range (IQR) of age for the different groups were 36 years (range 34–43) for good responders and 35 years (range 28–40) for poor. The male/female sex ratio was 1 : 2 in the good responders and 1 : 5 in the poor responders (P = 0·821). Comparison of immunological and virological data between groups of good and poor responders is shown in Table 1. Median CD4+ T cell counts at baseline were 174 cells/µl (IQR, 66–436) and 150 (IQR, 50–307) for good and poor responders, respectively (P = 0·602). Median of plasma RNA viral load at baseline was 5·1 log10 for good and 5·7 log10 for poor responders (P = 0·029). Good responders, by definition, maintained viral load below 200 copies of RNA/ml for at least 12 months. In contrast, median viral load among poor responders, was 4·8 log10 copies/ml after 6 months and 5·5 log10 copies/ml after 12 months of therapy. Thirteen of 16 good responders had received HAART at baseline. Seventeen of the 20 poor responders and three of the 16 good responders had received dual therapy. Seventy-five patients who were neither good nor poor reference responders were classified as intermediate responders.

Table 1.

CD38+ CD8+ cell percentages can discriminate between groups of reference responders (n = 16) and non-responders (n = 20).

| Baseline | Month 6 | Month 12 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medians | Medians | Medians | |||||||

| Resp | Non-resp | P | Resp | Non-resp | P | Resp | Non-resp | P | |

| CD4+ (absolute count) | 174 | 150 | 0·604 | 297·8 | 267·85 | 0·874 | 293·1 | 233·85 | 0·064 |

| CD4+ (delta) | 43 | 108 | 0·824 | 150 | 11 | 0·464 | |||

| CD38+ CD8 (%) | 92·02 | 97·01 | 0·028 | 78·32 | 94·93 | <0·0001 | 75·5 | 92·4 | <0·0001 |

| CD38+ CD8+ (delta) | 13·24 | 2·48 | 0·002 | 15·66 | 4·91 | <0·0001 | |||

| HLA-DR+ CD8+ (%) | 56·6 | 54·68 | 0·774 | 33 | 48·5 | 0·014 | 28·5 | 44 | 0·03 |

| HLA-DR+ CD8+ (delta) | 21·77 | 7·49 | 0·006 | 22·69 | 8·75 | 0·006 | |||

| CD38+ HLA-DR+ CD8+ (%) | 55·13 | 50·43 | 0·972 | 27·7 | 43·15 | 0·002 | 30·75 | 34·25 | 0·239 |

| CD38+ HLA-DR+ CD8+ (delta) | 22·73 | 10·63 | 0·017 | 19·87 | 15·89 | 0·234 | |||

| VL (log10) | 5·1 | 5·78 | 0·029 | 2 | 4·79 | <0·0001 | 2 | 5·46 | <0·0001 |

The analysis was performed on reference groups defined by stringent criteria of viral load levels after therapy. Comparisons between the two groups were made by the non-parametric Mann–Whitney U-test. The level of significance was set at P < 0·05. The strongest associations are highlighted in bold. CD38+ CD8+ T cell level has the best discriminatory capacity on treatment response.

Effect of treatment on virological and immunological parameters

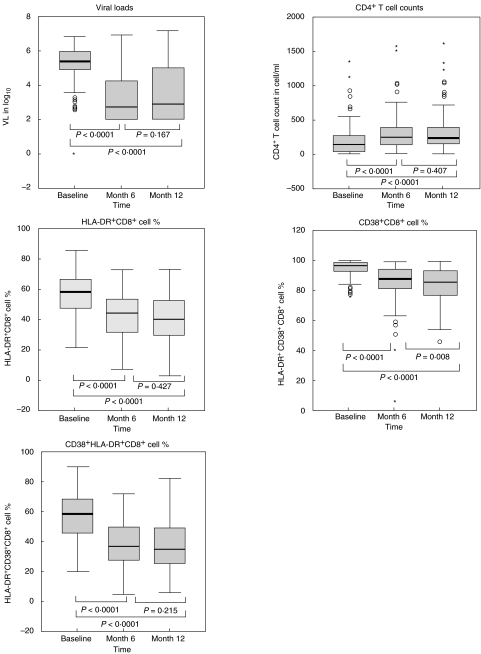

At 6 months of treatment, median values of all virological and immunological markers were significantly lower than baseline values (Wilcoxon's signed-ranks test, P < 0·0001, see Fig. 1) in the entire cohort of patients. Only the proportion of CD38+ CD8+ cells continued to decrease between months 6 and 12 post-therapy, suggesting that the major overall treatment-induced changes in CD4+ T cells count, HLA-DR+ CD8+, HLA-DR+ CD38+ CD8+ cellular expression and RNA viral load are achieved mainly within the first 6 months of therapy.

Fig. 1.

Effect of treatment on virological and immunological markers of HIV-1 infection in the entire group (n = 111). The analyses were performed on data generated from a cohort of 111 HIV-infected patients. Results are presented as log10 of RNA copy number (VL), absolute CD4+ T cell count or percentages of CD38+ cells within the CD8+ lymphocyte subsets. The box-plots represent the median, interquartile range (boxes) and the 5–95% data range (whisker caps). Asterisks and open circles represent extreme and outlier values, respectively. Comparison of each marker between different time-points have been made by the Wilcoxon signed-ranks tests for paired data. The level of significance was set at P < 0·05.

Association of immunological parameters with viral load

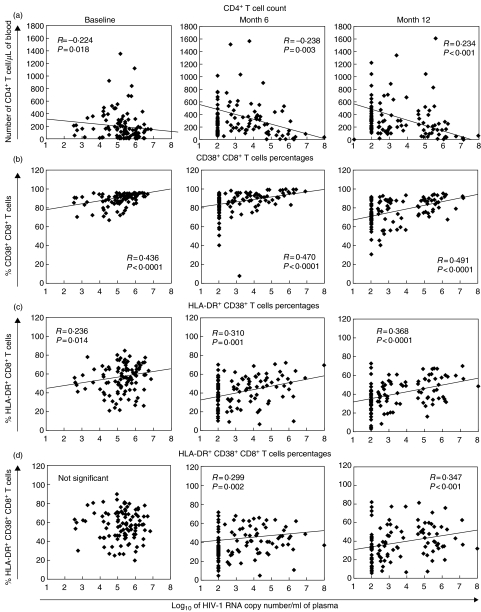

Overall, CD38+ CD8+ cell levels were the best correlate of viral load, at baseline (R = 0·44, P < 0·0001), at 6 months (R = 0·47, P < 0·0001) and at 12 months (R = 0·49, P < 0·0001) (Table 2, Fig. 2). Percentages of HLA-DR+ CD8+ and CD38+ HLA-DR+ CD8+ cells also correlated with treatment response, but were less consistent than CD38+ CD8+ percentages (Table 2). Because the CD38+ CD8+ T cell percentage has been shown to be less predictive than measures of CD38 fluorescence intensity [19], we also analysed the CD8 median fluorescence intensity (MFI) on CD8+ T cells in relation to viral load and CD4+ T cell counts. The CD38 median fluorescence intensity was calculated on the CD8bright T cell population using single-parameter histograms. This analysis improved the correlation between CD38+ CD8+ T cell measure and viral load at baseline (R = 0·563 versus R = 0·436) and month 12 (R = 0·583 versus R = 0·491) but not at month 6 (R = 0·407 versus R = 0·470, data not shown). The predictive value of absolute CD4 changes after ART initiation for detectable viral load was comparable to the predictive value of activation markers but only after 12 months of therapy (R = −0·451, P < 0·0001, Table 2). In the entire group, pretreatment levels of immune activation markers and viral load were correlated positively with the magnitude of ART-induced viral load changes (delta viral load). Correlation between delta viral load at month 6 and baseline values were R = 0·964, P < 0·0001 for viral load; R = 0·477, P < 0·0001 for CD38+ CD8+ cell percentage and R = 0·310, P = 0·002 for HLA-DR+ CD38+ cell percentage (data not shown). In contrast, there was no significant correlation between baseline and delta values of the immune activation parameters. This suggests that immunological but not virological response to ART depend on pre-existing levels of immune activation.

Table 2.

Correlation between immunological markers and viral load at base line, month 6 and month 12 post therapy in the entire group (n = 111).

| Viral load | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Month 6 | Month 12 | ||||

| R | P | R | P | R | P | |

| CD4+ (absolute count) | −0·224 | 0·018 | −0·283 | 0·012 | −0·0234 | 0·014 |

| CD4+ T change from baseline (delta) | −0·278 | 0·003 | −0·451 | <0·0001 | ||

| CD8+ CD38+ (%) | 0·436 | <0·0001 | 0·470 | <0·0001 | 0·491 | <0·0001 |

| CD8+ CD38+ (delta) | −0·486 | <0·000 | −0·478 | <0·0001 | ||

| CD8+ HLA-DR+ (%) | 0·236 | 0·014 | 0·31 | 0·001 | 0·368 | <0·0001 |

| CD8+ HLA-DR+ (delta) | −0·385 | <0·0001 | −0·413 | 0·000 | ||

| HLA-DR+ CD38+ CD8+ (%) | n.s. | n.s. | 0·299 | 0·002 | 0·347 | <0·0001 |

| HLA-DR+ CD38+ CD8+ (delta) | −0·380 | <0·0001 | −0·324 | 0·001 | ||

CD38+ CD8+ T cell percentages correlate better with viral load than CD4+ T cell count at any time-point of the observation period in the entire cohort of patients (n = 111). Correlations have been calculated by the non-parametric Spearman's rank order test. The level of statistical significance was set at P < 0·05. The strongest and most consistent correlations over time are highlighted in bold. Correlation between immunological markers and viral load at baseline, months 6 and 12 post-therapy on the entire cohort of patients (n = 11).

Fig. 2.

Correlation between HIV-1 viral load and immunological parameters. Correlation between absolute CD4+ T cell count (a) and percentages of CD8+ T cells expressing CD38 (b) and/or HLA-DR (c, d) and RNA viral load calculated at baseline, months 6 and 12 by the Spearman rank correlation test (n = 111). The solid line represents the linear correlation between the two datasets. The equation was calculated after the outlier points (i.e. corresponding to the value of the cut off-point of the viral load assay) were excluded from the analysis.

Predictive capacity of immunological markers on treatment response

We examined whether absolute CD4+ T cell count and percentages of CD38+ CD8+, HLA-DR+ CD8+ and HLA-DR+ CD38+ CD8+ cells can be used for discriminating response to treatment in a group of reference poor and good responders (extreme group). For each parameter, we plotted the true positive rate (sensitivity) and the false positive rate (1-specificity) in a receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curve for various cut-off values (see Fig. 3 for CD38+ CD8+ cell percentages at month 6). Areas under the curve (AUC) were used to assess and compare the discriminatory power of each immunological marker on good and poor response to ART in the extreme group (Table 3). The AUC of an ideal test = 1, whereas the AUC of a poor test = 0·5. In the present study, CD38+ CD8+ cell percentages were the best predictor of virological response with an associated AUC equal to 0·877 and 0·923 at months 6 and 12, respectively. Absolute CD4 counts and delta CD4 values did not have any discriminatory capacity on treatment response, with associated AUC close to 0·5 and P > 0·5 for both months 6 and 12 (Table 3). Overall, combining two or more criteria did not substantially improve the capacity of immunological markers to predict detectable viral load (data not shown). The use of CD38 MFI on CD8+ T cells instead of CD38+ CD8+ T cell percentages did not improve the sensitivity and specificity of the assay. Percentages and delta percentages (i.e. difference from baseline value) of HLA-DR+ CD8+ cells and CD38+ HLA-DR+ CD8+ cells were less consistent predictors of VL changes and virological response to the treatment (data not shown).

Fig. 3.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve of CD38+ CD8+ T cell percentages at month 6 in the extreme group (n = 36). The relationship between sensitivity (sens) and specificity (spec) of each immunological parameter to predict good or poor treatment response was studied in the extreme group (n = 36). Receiver operating characteristic curves were constructed by plotting the rate of true positive (sensitivity) against the rate of false positive (1-specificity) for all possible cut-off values at months 6 and 12. Only the ROC curve of CD38+ CD8+ T cell percentages at month 6 is presented. Cut-off values are displayed along the curve. The smallest cut-off values in the ROC curve is the minimum observed value minus 1 and the largest cut-off value is the maximum observed test value plus 1. All the other cut-off values are the average of two consecutive ordered observed values. The area under the ROC curve (AUC) is 0·877. The optimal operating point (90·91%), i.e. the cut-off giving the highest test accuracy, is associated with a relatively high rate of false negative (sens = 68·4%). This point lies on a 45° line closest to the north-west corner (0·1) of the ROC plot. For a more efficient screening of poor treatment response, a maximal sensitivity may be preferred by using 81·18% as the cut-off of positivity (sens = 100%; spec = 56·0%).

Table 3.

Areas under the curve (AUC), P value and 95% confidence interval corresponding to each imunological marker analysed on ROC curve for the discrimination of poor and good responders in the extreme groups (n = 36).

| Immunological markers | AUC | P value | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month 6 | CD4+ (absolute count) | 0·512 | 0·903 | 0·312–0·712 |

| CD4+ (delta) | 0·441 | 0·578 | 0·232–0·651 | |

| CD38+ CD8+ (%) | 0·877 | <0·0001 | 0·763–0·991 | |

| CD38+ CD8+ (delta) | 0·812 | 0·003 | 0·646–0·977 | |

| HLA-DR+ CD8+ (%) | 0·733 | 0·021 | 0·565–0·901 | |

| HLA-DR+ CD8+ (delta) | 0·733 | 0·027 | 0·547–0·919 | |

| CD38+ HLR-DR+ CD8+ (%) | 0·812 | 0·002 | 0·666–0·959 | |

| CD38+ HLR-DR+ CD8+ | 0·753 | 0·016 | 0·562–0·944 | |

| Month 12 | CD4+ (absolute count) | 0·46 | 0·69 | 0·259–0·660 |

| CD4+ (delta) | 0·51 | 0·924 | 0·305–0·716 | |

| CD38+ CD8+ (%) | 0·923 | <0·0001 | 0·825–1·021 | |

| CD38+ CD8+ (delta) | 0·818 | 0·003 | 0·669–0·967 | |

| HLA-DR+ CD8+ (%) | 0·716 | 0·033 | 0·527–0·902 | |

| HLA-DR+ CD8+ (delta) | 0·709 | 0·048 | 0·503–0·914 | |

| CD38+ HLR-DR+ CD8+ (%) | 0·644 | 0·155 | 0·453–0·835 | |

| CD38+ HLR-DR+ CD8+ | 0·607 | 0·309 | 0·399–0·815 |

AUC were compared for each immunological parameter studied, in order to determine the marker(s) with the best predictive capacity on treatment response in the extreme group. The 95% confidence interval and the P-value are derived from testing the hypothesis that the associated AUC is not different from 0·5 (random classification). The level of statistical significance was set at P <0·05. The highest values of AUC, which are associated with the best accuracy, are indicated in bold. CD38+ CD8+ T cells percentages had the best discriminatory capacity on virological response with the highest value of AUC at months 6 (AUC = 0·877) and 12 (AUC = 0·923). In contrast, the CD4+ T cell count did not have any discriminatory capacity on good and poor responders (AUC = 0·512 at month 6 and 0·416 at month 12, P >0·05).

Various cut-off values situated between the optimal operating point (i.e. the best trade-off between sensitivity and specificity) and the highest possible sensitivity point, were identified from the ROC curve of CD38+ CD8+ percentages at months 6 and 12. These cut-off values were used to calculate the true sensitivity and specificity of CD38+ CD8+ percentages in predicting the occurrence of detectable or undetectable viral load at months 6 and 12 in the entire group of patients (reference and intermediate responders, n = 111). The results are presented in Table 4. The accuracy of the assay was lower in the entire group compared to the extreme group, with sensitivity ranging from 75·4 to 87·3% and specificity from 46·2 to 76·6%.

Table 4.

Sensitivity and specificity associated with different cut-off values of CD38+ CD8+ cell percentages on good and poor treatment response in the extreme group (n = 36) and on positive and negative viral load in the entire group at months 6 and 12 post-treatment (n = 111).

| Prediction of poor response to ART in the extreme group (n = 36) | Prediction of detectable VL in the entire group (n = 111) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cut-off points (%) | Specificity | Sensitivity | Specificity | ||

| Month 6 | 90·91 (optimal operational point) | 68·4 | 93·7 | 54 | 76·6 |

| 85·57 | 68·4 | 75 | 65·1 | 63·8 | |

| 86·5 | 78·9 | 68·7 | 73 | 51·1 | |

| 85·63 | 89·5 | 56·2 | 77·8 | 48·9 | |

| 81·18 (maximal sensitivity point) | 100 | 56·2 | 87·3 | 42·6 | |

| Month 12 | 84·3 (optimal operation point) | 80 | 93·7 | 66·2 | 73·7 |

| 83·02 | 85 | 87·5 | 71·18 | 68·4 | |

| 82·64 | 85 | 75 | 71·8 | 63·2 | |

| 80·25 | 90 | 68·7 | 78·9 | 52·6 | |

| 78·88 (maximal sensitivity point) | 95 | 62·5 | 81·7 | 47·4 | |

Various cut-off values derived from the receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curves and ranging between the optimal operating points and the maximal sensitivity points (column 1 of the table) have been used to calculate sensitivity and specificity of CD38+ CD8+ T cells percentages in detecting poor response to the treatment in the extreme group (columns 2 and 3). These same cut-off values were applied to determine the true sensitivity and specificity of the test in the entire group (n = 111) at months 6 and 12 post-therapy (columns 4 and 5). In clinical practice, CD38+ CD8+ T cells percentages may be used as a screening tool for the detection of virological drug failure in the entire group. Hence, maximal sensitivity points (81·18% at month 6 and 78·88% at month 12) may be preferred to optimal operational point (90·91% at month 6 and 84·43% at month 12, shown in bold) as cut-off for positivity.

Discussion

The results of this study confirm and extend the findings that the percentage of CD8+ CD38+ cells constitutes a good correlate of HIV viral load in HIV-infected subjects, even during ART and taking into account the high non-specific immune activation background driven by helminth and/or other infections commonly present in African populations [20–22]. Our data support the observation of Weisman and colleagues, who reported that in populations with distinct immune activation profile, HIV infection becomes the dominant factor in the host/pathogen immune network, overriding any pre-existing immune activation background [23]. Relative numbers of CD38+ CD8+ lymphocytes were persistently decreased in response to ART similar to the level of viral replication, as previously described by Koblavi and colleagues [12]. Several other European and American studies on cohorts of children and adults infected with HIV reported a similar parallel decline of CD38+ CD8+ T cells and RNA viral load during HAART [24–26]. Percentages of CD38+ CD8+ lymphocytes were a much better correlate of viral load than HLA-DR+ CD8+ or HLA-DR+ CD38+ CD8+ lymphocytes and could also discriminate patients with a good virological response from those with a poor virological response. The superiority of CD38 over HLA-DR expression as a correlate of viral load has indeed been reported by others and may be related to the fact that HLA-DR expression on CD8 cells does not show a linear association with disease progression and is highest during ARC and thus not really correlated with viral load [19,27,28]. In contrast, the level of CD38 expression on CD8+ T lymphocytes has been shown to increase progressively with the more advanced HIV clinical stage [14]. CD38+ CD8+ percentages appear to be sensitive detectors of plasma virus burden. However, this marker would lack specificity if used as a screening test for the sensitive detection of early drug failure. If ART management were made on the basis of CD38+ CD8+ levels, 23·4–57·4% of patients with undetectable viral load would have their treatment switched inappropriately, even if optimal operating points were used as cut-off of positivity. The discrepancy between low viral load and persistently increased levels of immune activation may be due to the fact that our analysis was conducted on the entire population of CD8bright cells. It has been reported that the predictive capacity of CD38+ CD8+ T cell levels during disease progression or therapy-induced viral suppression resides predominantly in the pool of activated memory cells [29–31]. However, when only truly activated cells were considered, i.e. CD8+ T cells co-expressing both CD38 and HLA-DR, we did not find a stronger correlation between cellular immune activation and HIV viral load. In the present study, the use of CD38 MFI instead of CD38+ CD8+ T cell percentages did not improve the discriminatory capacity of the test between treatment success and treatment failure. The association of CD38 MFI on CD8+ T cells and HIV viral load was weaker than that reported by Deeks et al. in a cohort of patients recruited from the United States, presumably because of their lower background of cellular immune activation [32]. Persistence of high immune activation levels, even when the viral load falls below detection limits, may have several explanations. First, it suggests that the immune system recovers slowly and incompletely after clearance of virus from the plasma, as reported by others [33]. Secondly, residual immune activation in good virological responders may be related to ongoing viral replication in remote sites of the body such as the lymph nodes [34], which generates a source of emerging drug-resistant HIV strains [35,36]. A third important issue is that increased CD38+ CD8+ T percentages are not specific to HIV infection. Opportunistic viral infections such as hepatitis C and Epstein–Barr virus infections are also associated with an increase of CD8+ T cell activation [37,38]. Onset or reactivation of co-infections after the enrolment of the study participants may have affected their level of CD8+ T cell immune activation. The emergence of drug resistance due to the persistence of virus reservoirs as well as reactivation of opportunistic infections are both associated with rebounds of plasma HIV viral load [39,40]. In these cases, early prediction of virus replication by increased CD38+ CD8+ cell percentages would provide some advantage over the use of RNA viral load. Percentages of CD38+ CD8+ cells may, in fact, reflect the overall immune reconstitution status of the patient rather than simply being an indicator of viral load driven immune activation. This would explain the lack of specificity of this parameter in predicting therapeutic failure despite its correlation with HIV viral load. A crucial question in the context of resource-limited settings is whether or not the CD38+ CD8+ percentage could contribute to improve the cost–effectiveness of ART, as a marker of immune reconstitution in general and as opposed to the single use of CD4+ T count. Remarkably, 58% of the patients experiencing detectable viral replication after 6 months of ART showed an increase in their average CD4+ T cell counts of more than 75 cells/mm. This percentage of discordant responders was higher than the 7–17% described previously in European and American studies [41,42]. Although the CD4+ T cell count is the most important laboratory parameter to decide when ART has to be initiated, its frequent dissociation from viral load during treatment underlines its poor sensitivity as a single marker to monitor antiviral drug failure.

In the absence of RNA viral load test results, CD38+ CD8+ cell percentages could help to preselect patients who are more at risk of developing AIDS, despite the high rate of false positive tests in predicting early drug failure. A positive test may reveal the existence of occult virus reservoirs, early-onset or reactivation of opportunistic infections and, most importantly, exuberant inflammatory response of the recovering immune system toward latent infections during the immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS) [43]. Positive patients would receive extra care including an evaluation of treatment compliance, preventive or curative therapy against opportunistic infections and ultimately an adjustment or a switch of the ART.

Because HIV-infected patients in African countries are highly exposed to germs causing opportunistic infections (reviewed in [44]) and generally receive treatment at lower CD4 counts than European patients [45], the role of events such as IRIS may be as important as antiretroviral drug failure in progression to AIDS during ART. In this context, CD38+ CD8+ T cell percentages would offer an additional independent predictive value to the viral load on disease progression and provide a useful addition to the CD4 count for the management of ART in resource-limited settings. However, it should be emphasized that measurement of CD38 expression on CD8+ T cells is much more complicated than counting CD4 cells, although both are based on flow cytometry technology. The fact that CD38+ CD8+ T cell percentage and CD4+ T cell count can be performed with the same instrument, using simple affordable testing procedures on whole blood samples, is a significant advantage [46,47]. With the new generation of low-cost flow cytometers, this could reduce the cost of follow-up tests for ART to a $10 or less, which is 10 times less than the cost of an RNA viral load combined to a CD4 count using state-of-the-art technology. However, it has still to be demonstrated whether successful treatment response can be predicted by monitoring cellular immune activation in African populations with a relatively high immune activation background. Examining CD8+ T cell subsets such as CD38+ CD8+ CD45RO+ or CD38bright CD8+ T cells could be considered [29,30]. However, such improvement of prediction power would probably be at the expense of the test simplicity and affordability.

In summary, this study shows that although the CD38+ CD8+ T cell percentage is a good correlate of plasma HIV viral load in a cohort of Ivorian patients receiving ART, it lacks specificity to be used as an alternative marker for the detection of early virological drug failure. More in-depth analyses are needed to assess whether subsets of activated memory CD8+ T cells expressing CD38 have a better discriminatory capacity on the virological treatment response in the context of an African setting. We propose that CD38+ CD8+ percentages may, rather, be a marker of immune reconstitution and is still helpful in predicting the onset of AIDS independently of viral load. Further studies should be conducted in order to establish the relative contribution of opportunistic infections and IRIS in disease progression in African settings.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Belgian Directorate General for Development Cooperation (DGDC) AIDS impulse programme 2002, by the Projet Retro-CI and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and by the Belgian fonds voor Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek (FWO) Vlaanderen, grants G.0396–99 and G.0471·03 N. We thank Dr Jo Robays for his critical review of the statistical analysis.

References

- 1.Mellors JW, Kingsley LA, Rinaldo CR, et al. Quantitation of HIV-1 RNA in plasma predicts the outcome after seroconversion. Ann Intern Med. 1995;122:573–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-122-8-199504150-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cao YC, Qin L, Zhang L, et al. Virologic and immunologic characterisation of longterm survivors of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:201–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199501263320401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mellors JW, Rinaldo CR, Gupta P, et al. Prognosis in HIV-1 infection predicted by the quantity of virus in the plasma. Science. 1996;272:1167–70. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5265.1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O'Brien WA, Hartigan PM, Martin D, et al. Changes in plasma HIV-1 RNA and CD4+ lymphocyte count and the risk of progression to AIDS. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:426–31. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199602153340703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Katzenstein DA, Hammer SM, Hugues MD, et al. The relation of virologic and immunologic marker to clinical outcomes after nucleoside therapy in HIV-infected adults. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1091–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199610103351502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hugues MD, Johnson VA, Hirsch MS, et al. Monitoring plasma human immunodeficiency virus (HIV-1) RNA levels in addition to CD4+ lymphocytes count improve the assessment of antiretroviral therapic response. Ann Intern Med. 1997;126:929–45. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-126-12-199706150-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mellors JW, Muñoz A, Giorgi JV, et al. Plasma viral load and CD4+ lymphocytes as prognostic markers of HIV-1 infection. Ann Intern Med. 1997;126:946–54. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-126-12-199706150-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Giorgi JV, Lyles RH, Matud JL, et al. Predictive value of immunologic and virologic markers after long or short duration of HIV-1 infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002;29:346–55. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200204010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stephenson J. Cheaper HIV drugs for poor nations bring a new challenge: monitoring treatment. JAMA. 2002;288:151–3. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.2.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.WHO Guidelines. Scaling up antiretroviral therapy in resource-limiting setting. Available at: http://www.who.int/HIV_AIDS/first.html.

- 11.Bouscarat F, Levacher CM, Dazza MC, et al. Correlation of CD8 lymphocytes activation with cellular viremia and plasma HIV RNA levels in asymptomatic patients infected by human immunodeficiency virus type 1. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1996;12:17–24. doi: 10.1089/aid.1996.12.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koblavi-Dème S, Maran M, Kabran N, et al. Changes in levels of immune activation and reconstitution markers among HIV-1 infected Africans receiving antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2003;17(Suppl. 3):S17–22. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200317003-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bofill M, Akbar AN, Salmon M, Robinson M, Burford G, Janossy G. Immature CD45RA(low) RO(low) T cells in the human cord blood. I. Antecedents of CD45RA+ unprimed T cells. J Immunol. 1994;52:5613–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Levacher M, Hulstaert F, Tallet S, et al. The significance of activation markers on CD8 lymphocytes in human immunodeficiency syndrome: staging and prognostic value. Clin Exp Immunol. 1992;90:376–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1992.tb05854.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mocroft A, Bofill M, Lipman M, et al. CD8+, CD38+ lymphocyte percents: a useful immunological marker for monitoring HIV-1 infected patients. J AIDS. 1997;14:158–62. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199702010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kestens L, Vanham G, Gigase P, et al. Expression of activation antigens, HLA-DR and CD38, on CD8 lymphocytes during HIV-1 infection. AIDS. 1992;6:793–7. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199208000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nkengasong JN, Maurice C, Koblavi S, et al. Evaluation of HIV serial and parallel serologic testing algorithms in Abidjan, Côte d'Ivoire. AIDS. 1999;13:109–17. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199901140-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nkengasong JN, Maurice C, Koblavi S, et al. Field evaluation of a combination of monospecific enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays for type-specific diagnosis of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) and HIV-2 infections in HIV-seropositive people in Abidjan, Ivory Coast. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:123–7. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.1.123-127.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu Z, Cumberland WG, Hultin LE, Prince Harry E, Detels R, Giorgi JV. Elevated CD38 antigen expession on CD8+ T cells is a stronger marker for the risk of chronic HIV disease progression to AIDS and death in the multicenter AIDS cohort study than CD4+T cell count, soluble immune activation markers, or combination of HLA-DR and CD38 expression. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1997;16:83–92. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199710010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anglaret X, Diagbouga S, Mortier E, et al. CD4+ T-lymphocytes counts in HIV infection. Are European standards applicable to African patients? J Hum Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1997;14:361–7. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199704010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zekeng L, Sadjo A, Meli J, et al. T Lymphocytes subsets values among healthy Cameroonians. J Hum Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1997;14:82–3. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199701010-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kalinkovich A, Weisman Z, Burstein R, et al. Standard values of T-lymphocyte subsets in Africa. J Hum Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1997;17:183–4. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199802010-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weisman Z, Kalinkovitch A, Borkow G, et al. Infection by different HIV-1 subtypes (B and C) results in a similar immune activation profile despite distinct immune backgrounds. J AIDS. 1999;21:157–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Navarro J, Resino S, Bellón JM, et al. Association of CD8+ T lymphocyte subsets with the most commonly used markers to monitor HIV type 1 infection in children treated with highly active anti retroviral therapy. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2001;17:525–32. doi: 10.1089/08892220151126607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hunt PW, Martin JN, Sinclair E, et al. T cell activation is associated with lower CD4+ T cell gains in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients with sustained viral suppression during antiretroviral therapy. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2003;187:1534–43. doi: 10.1086/374786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Resino S, Bellón JM, Gurbindo MD, et al. CD38 expression in CD8+ T cells predicts virological failure in HIV type 1-infected children receiving antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38:412–7. doi: 10.1086/380793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nicholson JKAMC, Dougal JS, Spira TJ. Alteration of functional subsets of T helper and T suppressor cell population in acquired immunodeficiency syndrom (AIDS) and chronic unexplained lymphadenopathy. J Clin Immunol. 1985;5:269–74. doi: 10.1007/BF00929462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Prince HE, Arens L, Kleinman SH. CD4 and CD8 subsets define by dual-color cytofluorometry which distinguish symptomatic from asymptomatic blood donors seropositive for human immunodeficiency virus. Diagn Clin Immunol. 1987;5:188–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bofill M, Mocroft A, Lipman M, et al. Increased number of primed activated CD8+ CD38+ CD45RO+ T cells predict the decline of CD4+ T cells in HIV-1 infected patients. AIDS. 1996;10:827–34. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199607000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tilling R, Kinloch S, Goh L-E, et al. Parallel decline of CD8+/CD38++ T cells and viremia in response to quadruple highly active antiretroviral therapy in primary infection. AIDS. 2002;16:589–96. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200203080-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barry SM, Johnson MA, Janossy G. Increased proportion of activated and proliferating memory CD8+ T lymphocytes in both blood and lung are associated with blood HIV viral load. J AIDS. 2003;34:351–7. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200312010-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Deeks SG, Kitchen CMR, Liu L, et al. Immune activation set point during early HIV infection predicts subsequent CD4+ T cell changes independent of viral load. Blood. 2004;104:942–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-09-3333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martin M, Echevarria S, Leyva-Cobian F, et al. Limited immune reconstitution at intermediate stages of HIV-1 infection during one year of highly active antiretroviral therapy in antiretroviral-naive versus non-naive adults. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2001;20:871–9. doi: 10.1007/s100960100631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Garcia F, Vidal C, Plana M, et al. Residual low level of virus replication could explain the discrepancies between viral and CD4+ cell response in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients receiving antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30:392–4. doi: 10.1086/313660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lafeuillade A, Khiri H, Chadapaud S, et al. Persistence of HIV-1 resistance in lymph node mononuclear cell RNA despite effective HAART. AIDS. 2001;15:1965–9. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200110190-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schapiro JM, Winters MA, Vierra M, et al. Lymph node human immunodeficiency virus RNA levels and resistanc mutations in patients receivng high dose saquinavir. J Infect Dis. 1998;177:1730–3. doi: 10.1086/517380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lynne JE, Schmid I, Matud JL, et al. Major expansion of select CD8+ subset in acute Epstein–Barr virus infection: comparison with chronic human immunodeficiency virus disease. J Infect Dis. 1998;17:1083–7. doi: 10.1086/517400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Valdez H, Anthony D, Farukhi F, et al. Immune responses to hepatitis C and non-hepatitis antigens in hepatitis C virus infected and HIV-1 co-infected patients. AIDS. 2000;14:2239–46. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200010200-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Orenstein JM, Fox C, Wahl SM. Macrophage as a source of HIV during opportunistic infections. Science. 1997;276:1857–61. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5320.1857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Benwitch Z. Concurrent infections that rise the HIV viral load. J HIV Ther. 2003;8:72–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fessel WJ, Krowka JF, Sheppart HW, et al. Dissociation of immunologic and virologic responses to highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2000;23:314–20. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200004010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Grabar S, Le Moing V, Goujard C, et al. Clinical outcome of patients with HIV-1 infection according to immunologic and virologic response after 6 months of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133:401–10. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-133-6-200009190-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shelburne SA, III, Hamill R-J. The immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome. AIDS Rev. 2003;5:67–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Holmes C-B, Losina E, Walenski RP, et al. Review of human immunodeficiency virus type 1-related opportunistic infections in sub-Saharan Africa. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2002;8:137–43. doi: 10.1086/367655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Frater A-J, Dunn D-T, Beardall D-T, et al. Comparative response of African HIV-1-infected individuals to highly active antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2002;16:1139–46. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200205240-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Janossy G, Jani I, Gohde W. Affordable CD4(+) T-cell count on ‘single platform’ flow cytometers I. Primary gating. Br J Haematol. 2000;111:1198–208. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2000.02433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Greve B, Cassens U, Westerberg C, et al. A new no-lyse no wash flow-cytometric method for the determination of CD4 T cells in blood samples. Transfus Med Hemother. 2003;30:8–13. [Google Scholar]