Abstract

CXC chemokines are thought to play an important role at sites of inflammation. Because ELR+ CXC chemokines are expressed in different types of tonsillitis we investigated the role of the surface/crypt epithelium of human tonsils in producing ELR+ CXC chemokines: interleukin (IL)-8 (CXCL8), ENA-78 (CXCL5), GRO-α (CXCL1) and GCP-2 (CXCL6). Tonsillar tissue was obtained from patients undergoing tonsillectomy and chemokine expression was investigated by means of immunohistochemistry. A549 cells were used as a model to study kinetics of chemokine expression in epithelial cells. Cells were stimulated with tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α, lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and supernatants derived from aerobic/anaerobic Staphylococcus aureus strains. Chemokine expression was measured by quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). We observed epithelial expression of IL-8, GRO-α and GCP-2 in different types of tonsillitis, whereas ENA-78 was rarely expressed. In A549 cells abundant expression of ENA-78 was detected. IL-8 and GCP-2 are expressed in an acute type of tonsillitis whereas GRO-α was frequently detectable both in chronically and acutely inflamed tonsils. ENA-78 does not seem to play a pivotal role in tonsillitis in vivo.

Keywords: A549 cells, CXC, chemokines, inflammation, tonsillitis

Introduction

In tonsillitis, epithelial cells contribute actively to inflammatory processes as they represent the first-line defence of microbial attack. Anatomically, human palatine tonsils contain 10–30 blind-ending tubular, branched crypts extending through the full thickness of the organ. The reticulated crypt epithelium is a modified form of the stratified squamous epithelium that covers the remaining oropharynx including the outer surface of the tonsil [1,2]. In the crypts, luminal endocytosis of antigens by specialized microvilli-possessing epithelial cells (M-cells) occurs [3].

Because bacterial pathogens are found frequently in tonsillitis and these findings correlate with patient history, clinical findings and weight of the tonsils, many authors conclude that bacteria are involved in the pathogenesis of recurrent or hyperplastic tonsillitis. The most common pathogen in the human palatine tonsil core is Haemophilus influenzae (HI) followed by Staphylococcus aureus (SA) [4]. SA is known to produce various toxins, e.g. Staphylococcus aureusα-toxin, which generates a strong release of proinflammatory mediators in various target cells. Among those mediators chemokines are thought to play an important role in activating and attracting neutrophils at sites of inflammation.

Chemokines constitute a large family of chemotactic cytokines which are divided into four subfamilies based on the position of conserved cysteines: CXC, CC, C and CX3C chemokines [5]. CXC chemokines can be subdivided further into two subgroups depending on the presence or absence of the Glu-Leu-Arg sequence (ELR). ELR+ CXC chemokines [GRO-α/CXCL1, GRO-β/CXCL2, GRO-γ/CXCL3, epithelial cell-derived neutrophil attractant (ENA-78)/CXCL5, granulocyte chemotactic protein-2 (GCP2)/CXCL6, neutrophil activating protein (NAP2)/CXCL7 and interleukin (IL)-8/CXCL8] are potent activators and chemoattractants for neutrophils [6–10]. Due to these effects CXC chemokines can potentially attract and activate neutrophils in inflammatory processes.

As we have shown previously, ELR+ chemokines are expressed in different types of tonsillitis [11]. Because bacterial pathogens including SA are found frequently in human palatine tonsils [4] we investigated their potential effect in inducing expression of CXC ELR+ chemokines in epithelial cells. As the epithelium of the tonsillar crypts is a modified form of the stratified squamous epithelium that covers the outer surface of the tonsil [1] we used the human epithelial cell line A549 as a model to study expression and kinetics of the ELR+ CXC chemokines IL-8, GCP-2, ENA-78 and GRO-α in epithelial cells. However, an ideal model to study inflammatory responses of tonsillar epithelial cells does not exist, and of course the A549 epithelial cell cannot represent a surface/crypt epithelial cell. For induction of chemokines, tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α, lipopolysaccharide (LPS) or aerobic/anaerobic S. aureus supernatants (SAS) were used.

Methods

Patients

Tonsillar tissue was obtained from different patients suffering from hyperplastic tonsillitis (HT, n = 10, mean age (years)/standard deviation: 16·5 + 18·9), recurrent tonsillitis (RT, n = 9, mean age (years)/standard deviation: 22·7 + 13·2) and peritonsillar abscesses (PA, n = 11, mean age (years)/standard deviation: 23·5 + 15·6). HT was defined clinically as ‘kissing tonsils’ in children without a history of inflammation. Hyperplastic tonsils of adults with no history of tonsillitis were also considered as HT. Tonsils of patients with a history of more than three episodes of acute tonsillitis in a year were classified as RT. Acute inflamed tonsils surrounded by an abscess cavity were classified as PA. Informed consent was obtained from all patients and the study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Muenster, Germany.

Immunohistochemistry

Paraffin was resolved from tonsillar sections using decreasing concentrations of ethanol. Further steps were performed according to the instructions of the Dako-LSAB kit (no. K0679; Dako, GmbH, Hamburg, Germany). After inhibition of the endogenous peroxidase, polyclonal antibodies were added [IL-8: polyclonal goat antihuman IL-8 antibody, 1 : 200, AF-208-NA, R&D Systems, Wiesbaden, Germany; ENA-78: polyclonal goat antihuman antibody ENA-78, 1 : 200, AF254, R&D Systems; GRO-α (C-15): polyclonal goat-anti human antibody, 1 : 100, SC-1374, Santa Cruz, USA; GCP-2 (T16): polyclonal goat antihuman antibody, 1 : 100, SC-581B, Santa Cruz].

In cases of IL-8 and ENA-78 a universal biotinylated link-antibody served as secondary antibody. Subsequently streptavidin–biotin conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (HRPOD) was added. Sections were then incubated with DAB chromogen substrate for 5 min. For GRO-α and GCP-2, a rabbit antigoat peroxidase conjugated antibody (Dianova, 1 : 250, no. 305-035-045) served as secondary antibody. AEC chromogen substrate (Dako) was added for 30 min. Finally, sections were washed with Mayer's haematoxylin for 20 s.

Three different histological compartments (surface epithelium, crypt epithelium and high-endothelial venules (HEV) of the extrafollicular region) were investigated by light microscopy. Staining intensity was quantified by forming four groups based on the percentage of positive stained cells per microscopic field (I: 0–1%; II: 1–25%; III: 25–50%; IV: > 50% positive stained cells).

Cultivation of S. aureus/harvesting of supernatants

The S. aureus strain ATCC35556 was cultivated primarily on blood agar and then on TSB (Tryptone Soy Broth; Gibco Life Technologies, Eggenstein, Germany). Overnight cultures were harvested and optical density was determined at 500 nm. The number of bacteria was reduced by double centrifugation at 5000 r.p.m. for 15 min (Dassel, Schleicher and Schuell, Germany). Supernatants were then filtered (0·45 µm pore) to gain a sterile solution. Evidence of sterility was performed by cultivation of sterile supernatants on blood agar overnight with no signs of bacterial growth. For anaerobic growth an anaerobic cultivation for 5 days was necessary. Harvesting of supernatants was performed identically.

Cultivation and stimulation of A549 cells

A549 cells (ATTC CCL-185) were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA). Cells were grown in Ham's F12K medium (Gibco Life Technologies) and supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 µg/ml streptomycin (Sigma, Deisenhofen, Germany). A549 cells were cultured at 37°C, gassed with 5% CO2 and grown to 80% confluence. They were then split using trypsin (0·1%). Prior to stimulation, cells were incubated with Ham's F12K medium without FCS for 24 h.

A549 cells were stimulated with TNF-α (25 ng/ml, recombinant human TNF-α, Prepro Tech EC Ltd, London, UK), LPS (50 ng/ml, lipopolysaccharide, source Escherichia coli 055:B3, Sigma) or aerobic/anaerobic 10-fold diluted S. aureus supernatants (1 : 10, ATCC 35556, kindly donated by Dr Worlitzsch, Institute of Hygienic and Environmental Medicine, University of Tuebingen, Germany). For blocking experiments anti-TNF-α antibodies (1200 ng/ml, Prepro-Tech) were added. Quadruplicate detection of mRNA and protein expression levels was performed after 2, 6 and 24 h for both stimulation experiments and unstimulated controls.

Characterization and purity of A549 cells was examined by inverted phase contrast microscopy. Cell viability as assessed by trypan blue exclusion was greater than 95% in all experiments. At chosen points of time supernatants were harvested and protein levels were measured using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) technique. A549 cells were collected and lysed for the extraction of total RNA.

ELISA

ELISA tests for IL-8 (detection range > 10 pg/ml), ENA-78 (detection range > 15 pg/ml), GRO-α (detection range > 10 pg/ml) and GCP-2 (detection range > 1·6 pg/ml) were carried out according to the manufacturer's instructions (R&D Systems, Wiesbaden, Germany).

Extraction of total RNA/reverse transcription/cDNA synthesis

Total RNA was extracted according to the manufacturer's specifications (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) with an additional DNase digestion step (10 µl DNase, Qiagen). Total RNA was finally eluted in 50 µl of Rnase-free water (Qiagen). Subsequently, optical density of 2 µl of total RNA was measured. One µg of total RNA of each sample was used for reverse transcription.

Quantitative TaqMan polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

Quantitative PCR analysis was performed as described elsewhere [11]. To quantify mRNA gene expression a cDNA standard curve was used (r2 = 0·99). One unit of cDNA standard was defined as the amount of cDNA of cell line A549 that is synthesized after 60 min of incubation of 1 µg of total RNA and 4 units of reverse transcriptase at 37°C. PCR amplification was displayed as a Ct-value (threshold cycle) and compared with those of a standard curve. Ct-values of 33 or higher were excluded from further investigations. Samples were standardized using GAPD housekeeping gene expression as reference. Cytokine protein levels were t-tested and finally displayed as median + s.e.m. A P-value < 0·05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Immunohistochemistry of tonsillar tissue

Chemokines were detected in tonsillar tissue as shown in Table 1 and Fig. 1. Three different histological compartments were investigated: the tonsil's outer oropharyngeal epithelial layer was considered as surface epithelium in contrast to the deep branched crypt epithelium. The extrafollicular region was defined as the subepithelial space around the lymphoid follicles. This region containins T cells, dendritic cells, macrophages and specialized venules, the so-called high-endothelial venules (HEV).

Table 1.

Immunohistochemistry of CXC chemokines of different histological compartments (surface epithelium, crypt epithelium and high-endothelial venules (HEV) of the extrafollicular region). HT: hyperplastic tonsillitis. RT: recurrent tonsillitis. PA: peritonsillar abscess. Absent (0–1%), low (1–25%), intermediate (25–50%) or high expression (>50% positive stained cells) of chemokines is represented by the percentage of positive stained cells per microscopic high power field

| Disease | Compartment | IL-8 stained cells | ENA-78 stained cells | GRO-α stained cells | GCP-2 stained cells |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HT (n = 10) | Surface epithelium | 0–1% | 0–1% | 25–50% | 25–50% |

| Crypt epithelium | 1–25% | 0–1% | 1–25% | 1–25% | |

| HEV | 0–1% | 0–1% | 1–25% | 1–25% | |

| RT (n = 9) | Surface epithelium | 0–1% | 0–1% | 25–50% | 25–50% |

| Crypt epithelium | 25–50% | 0–1% | 1–25% | 1–25% | |

| HEV | 0–1% | 0–1% | 25–50% | 1–25% | |

| PA (n = 11) | Surface epithelium | > 50% | 0–1% | > 50% | > 50% |

| Crypt epithelium | > 50% | 0–1% | 25–50% | 25–50% | |

| HEV | 0–1% | 0–1% | 25–50% | 25–50% |

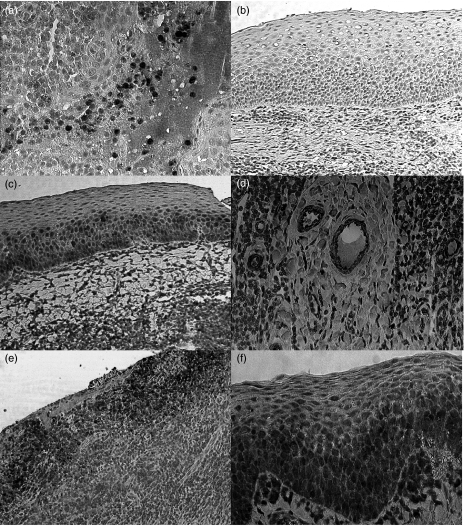

Fig. 1.

Immunohistochemistry of CXC chemokines in different types of tonsils. (a) Interleukin (IL)-8 expression of the crypt epithelium and of intracryptal cells. (b) Failed ENA-78 expression in the surface epithelium of hyperplastic tonsillitis (HT). (c) GRO-α expression in the surface epithelium of recurrent tonsillitis (RT). (d) GRO-α expression of HEV in the extrafollicular region of RT. (e) IL-8 stained cells in the surface epithelium of PA. (f) GCP-2 stained cells in the surface epithelium of PA.

In HT and RT IL-8 stained cells were found in the crypt epithelium and in the crypts next to degenerated cells and cellular debris (Fig. 1a). IL-8 was neither detectable in the extrafollicular region nor in the surface epithelium of HT and RT. However, in PA an abundant IL-8 expression was found in the surface epithelium (Fig. 1e). HEV showed no expression of IL-8. GRO-α protein was frequently detectable in the surface- and the crypt epithelium in HT, RT and PA (Fig. 1c). In the latter an abundant expression was found. Remarkably, GRO-α was detectable in HEV of all three disease types (Fig. 1d) ENA-78 protein was not detectable in any region of HT and RT (Fig. 1b). In PA a few ENA-78 stained cells were detectable in the crypts. Also, ENA-78 stained cells were found occasionally in the extrafollicular region. GCP-2 stained cells were found in all histological compartments of HT, RT and PA (Fig. 1f). In HT and RT an abundant GCP-2 expression was found in the surface epithelium.

Stimulation of A549 cells

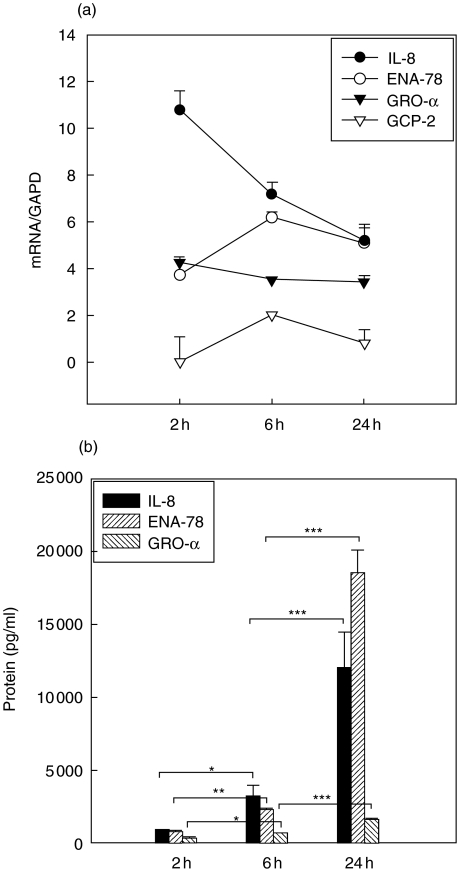

TNF-α stimulation

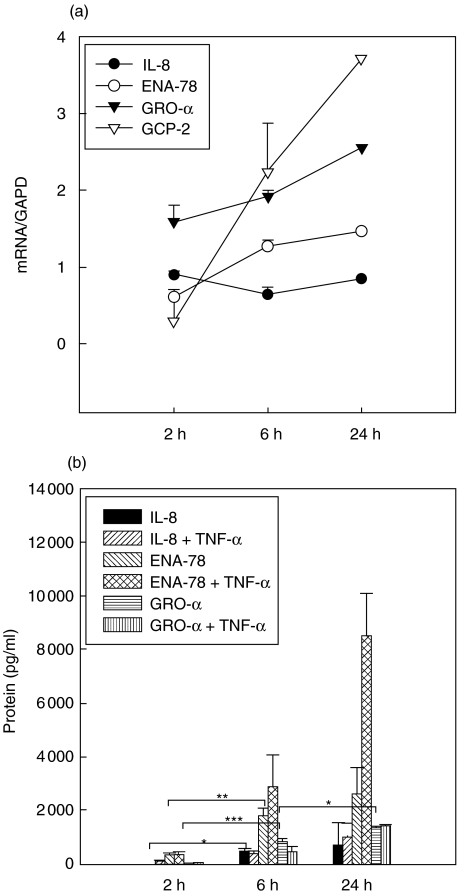

mRNA levels of IL-8, ENA-78 and GRO-α increased within the first two hours of stimulation and remained on an elevated level for more than 24 h compared with unstimulated controls (Fig. 2a, mRNA controls not shown). In the case of IL-8 a rapid up-regulation was found within the first 2 h followed by a slow decrease of IL-8 mRNA. IL-8 and ENA-78 protein levels increased significantly after 2 h of stimulation. GRO-α mRNA remained on a constant expression level, whereas an increase was observed in the case of the protein. GRO-α protein levels were more than 20-fold lower than those of IL-8 or ENA-78. GCP-2 mRNA was inducible but not translated in GCP-2 protein (GCP-2 protein not shown, Fig. 2b).

Fig. 2.

(a,b) Tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α induction. Kinetics of mRNA (a) and protein expression [enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), b] of CXC chemokines in A549 cells over 24 h. Symbols in (a) represent medians + s.e.m. of chemokine expression with GAPD as reference. Chemokine expression after 6 and 24 h was significantly different (P < 0·05) compared to unstimulated controls (not shown). Columns in (b) represent median + s.e.m. of chemokine concentration in pg/ml. *P < 0·05; **P < 0·005; ***P < 0·0005.

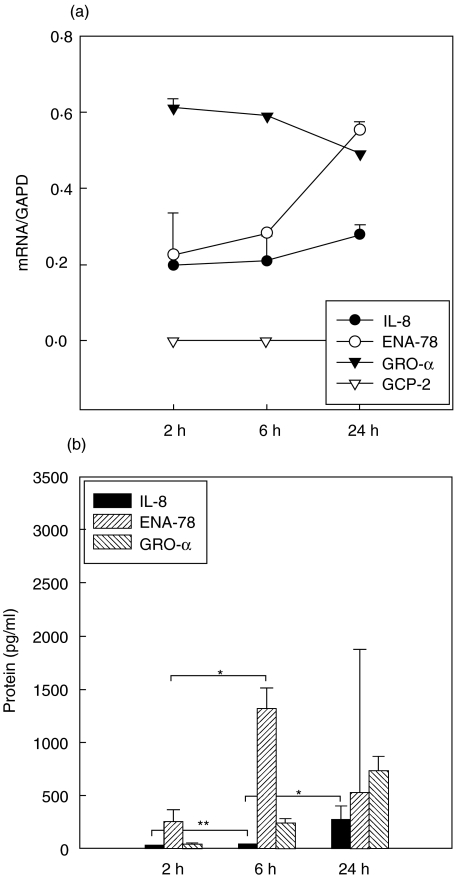

LPS stimulation

mRNA expression levels of IL-8, ENA-78 and GRO-α increased significantly after 6 h of stimulation. GCP-2 mRNA was not inducible (Fig. 3a). IL-8 protein did not increase before 24 h after stimulation. ENA-78 mRNA expression increased after 6 h with a corresponding increase of ENA-78 protein. GRO-α protein increased significantly after 6 h and was more highly expressed after 24 h than IL-8 or ENA-78 (Fig. 3b).

Fig. 3.

(a,b) Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) induction. Kinetics of mRNA (a) and protein expression [enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), b] of CXC chemokines in A549 cells over 24 h. Symbols in (a) represent medians + s.e.m. of chemokine expression with GAPD as reference. Chemokine expression after 6 and 24 h was significantly different (P < 0·05) compared to unstimulated controls (not shown). Columns in (b) represent median + s.e.m. of chemokine concentration in pg/ml. *P < 0·05; **P < 0·005.

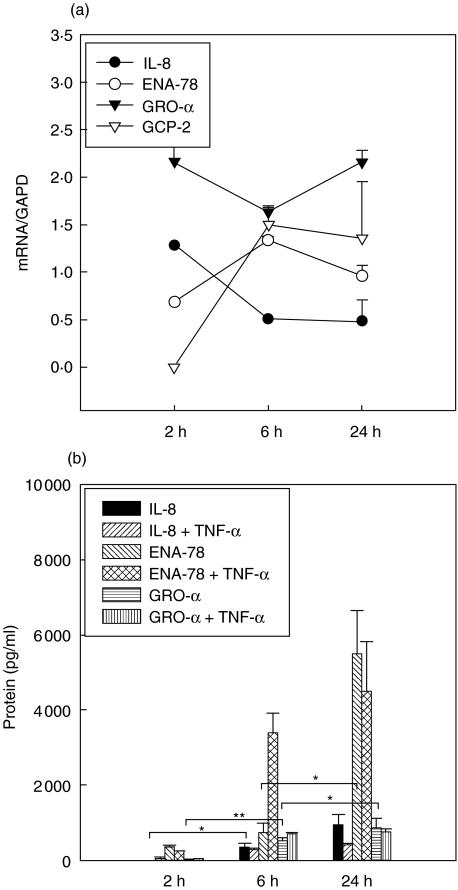

Stimulation with aerobic S. aureus supernatants

An increased expression of IL-8 mRNA was observed after 2 h and was followed by an increase of IL-8 protein after 6 h of stimulation. ENA-78 protein was significantly induced by aerobic supernatants after 24 h, whereas ENA-78 mRNA expression increased after only 6 h. GRO-α mRNA was constantly up-regulated, resulting in an increase of GRO-α protein expression after 6 h. Increased GCP-2 mRNA expression was observed after 6 h but GCP-2 protein expression was not detectable at any time. Addition of anti-TNF-α antibodies did not influence expression kinetics of IL-8 and GRO-α, but in the case of ENA-78 there was an earlier increase of ENA-78 protein expression after 6 h (Fig. 4a,b).

Fig. 4.

(a,b) Induction by aerobic Staphylococcus aureus supernatants. Kinetics of mRNA (Fig. 4a) and protein expression [enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), b] of CXC chemokines in A549 cells over 24 h. Symbols in (a) represent medians + s.e.m. of chemokine expression with GAPD as reference. Chemokine expression after 6 and 24 h was significantly different (P < 0·05) compared to unstimulated controls (not shown). Columns in (b) represent median + s.e.m. of chemokine concentration in pg/ml. *P < 0·05; **P < 0·005.

Stimulation with anaerobic S. aureus supernatants

IL-8 and ENA-78 mRNA expression increased significantly after 6 h of stimulation and a corresponding increase of IL-8 and ENA-78 protein was observed. GRO-α mRNA was constantly up-regulated and an increasing GRO-α protein expression was found. Addition of anti-TNF-α antibodies did not influence IL-8 and GRO-α expression. In the case of ENA-78 an increased protein expression was detected after 24 h (Fig. 5a,b).

Fig. 5.

(a,b) Induction by anaerobic Staphylococcus aureus supernatants. Kinetics of mRNA (a) and protein expression [enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), b] of CXC chemokines in A549 cells over 24 h. Symbols in (a) represent medians + s.e.m. of chemokine expression with GAPD as reference. Chemokine expression after 6 and 24 h was significantly different (P < 0·05) compared to unstimulated controls (not shown). Columns in (b) represent median + s.e.m. of chemokine concentration in pg/ml. *P < 0·05; **P < 0·005; ***P < 0·0005.

Discussion

CXC chemokines are expressed selectively in different disease entities of human tonsils, as we have shown previously [11]. We demonstrated that both IL-8 and GRO-α were up-regulated in acute inflammation, whereas GRO-α dominated in chronic inflammation. IL-8 represents the most potent neutrophil chemotactic and activating protein among the CXC ELR+ chemokines [7] and exerts its effects by binding at the receptors CXCR1 and CXCR2 [12]. This binding characteristic is also shared by GCP-2, which was originally isolated from conditioned medium of cytokine stimulated MG-63 osteosarcoma cells [6].

In the present study we demonstrated that IL-8 mRNA and IL-8 protein were up-regulated rapidly by TNF-α within the first 2 h after stimulation. These results imply a potential role of IL-8 in the onset of inflammatory processes in epithelial cells. An almost identical course of IL-8 expression was found in the case of stimulation with bacterial supernatants. Addition of anti-TNF-α antibodies did not change expression kinetics. This observation suggests that induction of IL-8 in A549 cells by bacterial antigens might be independent of TNF-α and might therefore be exerted via an alternative pathway. Support for such a hypothesis is gained from recent studies proposing a pathogen associated molecular pattern (PAMP), which can induce chemokine synthesis via a toll-like receptor system [13]. In addition, we have recently shown GRO-α and IL-8 to be inducible by bacterial supernatants in nasal epithelial cells and fibroblasts [14]. LPS proved to be a poor inductor at a concentration of 50 ng/ml of chemokine expression in A549 cells as expression levels were up to 10-fold lower in comparison with TNF-α.

Immunohistochemistry revealed IL-8-positive stained cells in the crypt epithelium of all three types of tonsillitis with a pronounced presence of IL-8-positive stained cells in PA. In comparison to HT and RT IL-8 stained cells were observed in the surface epithelium of PA only. As observed previously by others, we did not find IL-8 expression in the extrafollicular regions [15]. Sources of IL-8 production include neutrophils [16,17], which have been observed in the epithelium of acute and chronically infected tonsils [18]. Taken together, our observations suggest that IL-8 is expressed mainly by the surface/crypt epithelium and by neutrophils in an acute inflammatory situation which is observed in PA in vivo.

The second CXC chemokine binding both CXCR1 and CXCR2, GCP-2 has a weaker potential to activate neutrophils in comparison with IL-8 [6], but might play a role in special conditions of inflammatory processes. Our studies revealed that GCP-2 protein expression was not inducible in A549 cells by TNF-α. These findings are in accordance with the studies by Rovai et al., who could not induce expression of GCP-2 in A549 cells [19], although additional investigations (data not shown here) with IL-1β as stimulator revealed successful induction of chemokine synthesis. A recent study by Wuyts et al. suggests that GCP-2 is a typical mesenchymal cell-derived chemokine that was best induced by IL-1β whereas TNF-α was a poor inductor [17].

In tonsils GCP-2 is frequently expressed by epithelial cells. However, GCP-2 is not expressed exclusively by epithelial cells but by various other types of cells including macrophages and mononuclear monocytes [17]. In fact, we could observe other non-epithelial cells which we did not characterize further in our immmunohistochemistry expressing GCP-2 protein. These cells could potentially contribute to the GCP-2 expression in human tonsils. Taken together, GCP-2 might be involved in acute and chronic inflammation as well. In PA an acute inflammatory situation dominates and here a strong GCP-2 expression in the surface epithelium was found.

In contrast to the strong expression of GCP-2 in the surface epithelium of HT, RT and PA a weak expression was observed for ENA-78, which was discovered originally by Walz et al. in the A549 cell line [10]. Against that background it is hardly surprising that we observed a strong induction of ENA-78 protein by TNF-α in A549 epithelial cells. These experiments and those of Walz et al. showed that TNF-α was a good inductor for ENA-78 in A549 cells. Furthermore, other epithelial cells are known to be a major source of ENA-78 expression because ENA-78 was detected in the intestinal epithelium of inflammatory bowel disease and in the human intestinal epithelial cell-line Caco-2 [20]. Another source of ENA-78 production is human monocytes [21].

However, in HT, RT and PA ENA-78 protein was detectable in small amounts only [11]. Because the A549 cell is not an ideal model for a tonsillar epithelial cell, we expected differences between cell culture results and immunohistochemistry. Moreover, in a very recent study ENA-78 protein was detected in tumour cells and monocytes/macrophages of patients suffering from bronchioloalveolar carcinoma (BAC), whereas it was not detectable in the normal lung [22]. These and our own results showed that ENA-78 expression seems to be very restricted, as it could not be detected in the normal lung, but under special conditions was found in BAC or in inflammatory bowel disease [20]). Taken together, we conclude that ENA-78 is expressed under special conditions only and probably does not play a major role in human tonsillitis.

GRO-α exerts activating and chemotactic effects on neutrophils and is produced by a variety of cells including monocytes, endothelial cells, fibroblasts and synovial cells after stimulation with TNF-α, IL-1 or LPS [23]. Our results are in accordance with these findings, as GRO-α protein was inducible by TNF-α and LPS after 2 h. GRO-α mRNA levels remained almost constant from that point. Stimulation of A549 cells with aerobic or anaerobic S. aureus supernatants resulted in similar expression levels. As a result, frequent GRO-α protein expression was observed during the first 24 h after stimulation, implying a possible role of GRO-α in maintaining inflammatory processes, as mentioned previously by Schroeder et al., who investigated GRO-α expression in psoriasis [24]. Moreover, we have recently observed higher levels of GRO-α protein in RT, which represents a chronic inflammatory disease, than in PA or HT [11]. In addition, immunohistochemistry revealed a frequent GRO-α expression in HEV of RT, implying a regulatory function in leucocyte trafficking.

In conclusion, we were able to demonstrate expression of ELR+ CXC chemokines in different types of tonsillitis and in A549 cells. Because IL-8 and GCP-2 were expressed abundantly in the surface epithelium of an acute type of tonsillitis, these results imply a role at sites of acute tonsillar inflammation. By contrast, ENA-78 was almost undetectable and does not seem to play a pivotal role in tonsillitis in vivo. GRO-α was expressed frequently in different histological compartments, regardless of the disease type, and seems to be involved in acute and chronically inflamed processes. Further studies need to be performed to elucidate chemokine involvement in tonsillar diseases.

References

- 1.Perry ME. The specialized structure of crypt epithelium in the human palatine tonsil and its functional significance. J Anat. 1994;185:111–27. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nave H, Gebert A, Pabst R. Morphology and immunology of the human palatine tonsil. Anat Embryol. 2001;204:367–73. doi: 10.1007/s004290100210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gebert A. Identification of M-cells in the rabbit tonsil by vimentin immunohistochemistry and in vivo protein transport. Histochem Cell Biol. 1995;104:211–20. doi: 10.1007/BF01835154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lindroos R. Bacteriology of the tonsil core in recurrent tonsillitis and tonsillar hyperplasia – a short review. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl. 2000;43:206–8. doi: 10.1080/000164800454404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zlotnik A, Joshi O. Chemokines: a new classification system and their role in immunity. Immunity. 2000;12:121–7. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80165-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Proost P, De Wolf-Peeters C, Conings R, Opdenakker G, Billiau A, Van Damme J. Identification of a novel granulocyte chemotactic protein (GCP-2) from human tumor cells: in vitro and in vivo comparison with natural forms of GRO, IP-10 and IL-8. J Immunol. 1993;150:1000–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wuyts A, Proost P, Van Damme J. Interleukin-8 and other CXC chemokines. In: Thomson AW, editor. The cytokine handbook. 3. London, UK: Academic Press; 1998. pp. 271–311. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang D, Richmond A. MGSA/ GRO. In: Oppenheim JJ, Feldmann M, editors. Cytokine reference: a compendium of cytokines and other mediators of host defense. London, UK: Academic Press; 2000. pp. 1023–48. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brandt E, Petersen F, Ludwig A, Ehlert JE, Bock L, Flad HD. The beta-thromglobulins and platelet factor 4: blood platelet derived CXC chemokines with divergent roles in early neutrophil regulation. J Leukoc Biol. 2000;67:471–8. doi: 10.1002/jlb.67.4.471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walz A, Burgener R, Car B, Baggiolini M, Kunkel SL, Strieter RM. Structure and neutrophil-activating properties of a novel inflammatory peptide (ENA-78) with homology to interleukin-8. J Exp Med. 1991;174:1355–62. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.6.1355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rudack C, Jörg S, Sachse F. Biologically active neutrophil chemokine pattern in tonsillitis. Clin Exp Immunol. 2004;1 35:511–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2003.02390.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murphy PM, Baggiolini M, Charo IF, et al. International union of pharmacology. XXII. Nomenclature for chemokine receptors. Pharmacol Rev. 2000;52:145–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beutler B, Gelbart T, West C. Synergy between TLR2 and TLR4: a safety mechanism. Blood Cell Mol Dis. 2001;27:728–30. doi: 10.1006/bcmd.2001.0441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rudack C, Stoll W, Hermann W. Primäre nasale Epithelzellen und Fibroblasten haben entzündungsfördernde Eigenschaften. HNO. 2003;51:480–5. doi: 10.1007/s00106-002-0754-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Andersson J, Abrams J, Bjork L, et al. Concomitant in vivo production of 19 different cytokines in human tonsils. Immunology. 1994;83:16–24. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rudack C, Hermann W, Eble J, Schroeder JM. Neutrophil chemokines in cultured nasal fibroblasts. Allergy. 2002;57:1159–64. doi: 10.1034/j.1398-9995.2002.23748.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wuyts A, Struyf S, Gijsbers K, et al. The CXC chemokine GCP-2/CXCL6 is predominantly induced in mesenchymal cells by interleukin-1beta and is down regulated by interferon gamma: comparison with interleukin-8/ CXCL8. Lab Invest. 2003;83:23–34. doi: 10.1097/01.lab.0000048719.53282.00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ebenfelt A, Ivarrson M. Neutrophil migration in tonsils. J Anat. 2001;198:497–500. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-7580.2001.19840497.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rovai LE, Herschman HR, Smith JB. Cloning and characterization of the human granulocyte chemotactic protein-2 gene. J Immunol. 1997;158:5257–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keates S, Keates AC, Mizoguchi E, Bhan A, Kelly CP. Enterocytes are the primary source of the chemokine ENA-78 in normal colon and ulcerative colitis. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:75–82. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1997.273.1.G75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schnyder-Candrian S, Walz A. Neutrophil activating peptide ENA-78 and IL-8 exhibit different patterns of expression in lipopolysaccharide and cytokine stimulated human monocytes. J Immunol. 1997;158:3888–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wislez M, Philippe C, Antoine M, et al. Upregulation of bronchioloalveolar carcinoma-derived C-X-C chemokines by tumor infiltrating inflammatory cells. Inflamm Res. 2004;53:4–12. doi: 10.1007/s00011-003-1215-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Geiserls T, Dewald S, Ehrengruber M, Clark-Lewis I, Baggiolini M. The interleukin-8 related chemotactic cytokines GRO-α, GRO-β and GRO-γ activate human neutrophil and basophil leukocytes. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:15419–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schroeder JM. Identification and structural characterization of chemokines in lesional skin material of patients with inflammatory skin disease. Meth Enzymol. 1997;288:266–97. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(97)88019-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]