Abstract

It has been shown recently that different genotypes of Mycobacterium tuberculosis induce distinct immune responses in the host, as reflected by variations in cytokine and iNOS expression. Because these molecules are probably regulated by multiple factors in vivo this complex phenomenon was partially analysed by assessing cytokine and iNOS expression by real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) in an in vitro model of bone marrow-derived macrophages infected with three different M. tuberculosis genotypes: Canetti, H37 Rv and Beijing. Although the three genotypes induced production of iNOS and the different cytokines tested at 24 h post-infection, macrophages infected with the Beijing isolate expressed the highest levels of mRNA for iNOS, interleukin (IL)-1β, tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α, IL-12 cytokines and lower levels of IL-10 compared with cells infected with other genotypes. This expression pattern has been associated with infection control, but during infection in vivo with the Beijing genotype it is lost upon progression to chronic phase. The failure to control infection is likely to be influenced by cytokines produced by other cell types and bacterial molecules expressed during the course of disease. Results presented in this work show that each genotype has the ability to induce different levels of cytokine expression that could be related to its pathogenesis during infection.

Keywords: bone marrow derived macrophages, cytokine expression, Mycobacterium tuberculosis genotypes

Introduction

Tuberculosis is the most deadly infectious diseases in the world. It is estimated that 2 million people die of tuberculosis each year. The causative agent of this disease is Mycobacteium tuberculosis (Mtb), an intracellular pathogen that survives and replicates mainly in macrophages.

Development of tuberculosis is determined by factors associated with both the host and the bacteria that cause the disease. It is known that polymorphism in nramp1[1], major histocompatibility complex (MHC) [2], Toll-like receptor (TLR)-2 [3], and vitamin D receptor [4] genes can predispose to the development of tuberculosis in humans. Similarly, alterations in some components of the immune system facilitate the development of the disease, a fact that has been observed in individuals infected with HIV and in those who have altered expression of interferon (IFN)-γ and interleukin (IL)-12 receptors [5–7].

The effects of different M. tuberculosis (Mtb) strains on the development of the disease have also been analysed. Studies with clinical isolates have shown interesting aspects about the infection. It has been demonstrated that lungs of mice, infected with the low virulence strain CDC1551, produce high levels of TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-12, and IL-6 mRNA compared to those infected with the H37Rv strain [8]. Another study that analysed the in vivo and in vitro effects of the high virulence strain HN878 revealed lower levels of cytokines type I and a higher expression of IFN type I in the lungs of infected mice [9].

Recently, it was shown that mice infected with strains of Mtb of different genotypes showed a different behaviour of the disease that was related to the genotype of the infecting bacteria. The Canetti genotype induced low or null mortality, whereas the Beijing genotype induced the highest mortality in a very short time in the same mice strain. Initially, after Beijing strain infection, a high but transient expression of TNF-α and iNOS was seen, whereas the Canetti strain induced a high and sustained TNF-α and iNOS mRNA expression [10]. Because the expression of cytokines and iNOS is likely to be affected by multiple factors in vivo, we decided to syudy this phenomenon in vitro by analysing the ability of each of the three different Mtb genotypes to influence cytokine and iNOS expression in murine macrophages infected with each genotype separately.

Materials and methods

Mycobacterial growth

Three strains of the Mtb complex were used: H37Rv; 9501000 (Beijing genotype), which was isolated from Beijing, China; and 9600046 (Canetti genotype), isolated at the Pasteur Institute. The last two strains were kindly provided by the National Institute of Public Health and the Environment from the Netherlands. All strains were grown in Middelbrook 7H9 medium (Difco Laboratory, Detroit, MI, USA) during 4 weeks, harvested, aliquoted and frozen at −70°C until used.

Bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDM)

Macrophages were obtained as described previously [11]. Briefly, bone marrow from femurs of ∼8-week-old BALB/c mice was dispersed and cultured at 37°C and 5% CO2 in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) containing 100 U/ml penicillin (Gibco BRL, Grand Island, NY, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) (Hyclone, Road Logan, UT, USA), 10% equine serum (Hyclone) and 15% of 7 days’ culture supernatant from L-929 cells. Cells were used after 10 days of culture, when more than 90% of cells were positive for CD11b, a monocyte/macrophage marker.

Macrophage infection with Mtb strains

BMDM (3 × 106) were infected for 3 h in six-well plates with different strains of Mtb in DMEM supplemented with 5% FCS at a ratio of 15 colony-forming units (CFU) per macrophage. After this time, cells were extensively washed with Hanks's balanced salt solution (HBSS) (Gibco BRL) to eliminate nonphagocytosed bacteria. Finally, cells were incubated in DMEM + 5% FCS to complete 6 and 24 h post-infection (hpi). Nearly 70% of BMDM were infected as detected by Kinyoun staining. Four different experiments were performed.

Determination of colony-forming units (CFUs)

BMDM (2 × 105) were harvested at 6 and 24 h following infection. The supernatant was discarded, and infected cells were lysed with 0·5 ml of 0·25% sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS), neutralized with 0·5 ml of 5% bovine serum albumin. The suspension was vortexed for 10 s to disperse bacteria and 0·1 ml was diluted (10−1, 10−2, 10−3), 20 µl of each dilution was placed on Middlebrook 7H10 agar plates (Difco) supplemented with oleic acid–albumin–dextrose–catalase enrichment. The plates were incubated for 2 weeks at 37°C (performing CFU reading every 24 h from day 12 onwards). Results are presented as the mean of CFU ± standard deviation (s.d.).

RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis

After infection, supernatants were eliminated and attatched cells were lysed with 1 ml Trizol reagent (Invitrogene, Carlsbad, CA, USA). RNA was extracted according to the manufacturer's instructions and RNA integrity was confirmed by formaldehyde denaturing agarose gel electrophoresis. RNA was quantified through optical density at 260 nm in a Smart Spec 300 (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA).

cDNA was synthesized annealing 2 µg total RNA with 1 µg oligo dT12-18 (Amersham, Buckinghamshire, UK) in a volume of 10 µl at 70°C during 10 min. Then, samples were chilled on ice and 10 µl of 2× mix reaction was added [final concentration: 1× first strand buffer, 10 m m DTT, 250 µm dNTPs and 200 U M-MLVRT (Gibco BRL)]. Reaction was incubated at 37°C for 1 h and 95°C for 5 min

Real-time reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)

This was performed in a GeneAmp 5700 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA), as described previously [12]. Briefly, reactions were performed in 50 µl final volume, containing 0·5× of SYBR Green I (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA), 1× PCR buffer, 0·2 m M of each primer (see Table 1), 2·5 m M MgCl2, 0·2 m M dNTPs, 1·25 U AmpliTaq DNA polymerase (Invitrogene) and 5 µl of cDNA diluted 1 : 5 in water. Reactions were cycled 35 times consisting of 95°C for 30 s, 60°C for 30 s, 72°C for 1 min and temperature of fluorescence acquisition (FA) for 5 s. Data were analysed with the GeneAmp 5700 SDS software version 1·3 (Applied Biosystems). Positive cytokine expression controls were set up incubating BMDM for 24 h with 10 µg/ml lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (Sigma). For positive iNOS expression control, cells were incubated with 10 µg/ml LPS plus 100 U IFN-γ (R&D Systems, Minneapolis MN, USA). Values are represented as ratios of cytokine/GAPDH ± standard deviation (s.d.). Statistical analysis was performed with Student's t-test.

Table 1.

Sequence of primers used in real-time reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), amplicon sizes and their melting temperatures are shown

| Target | Sequences | Amplicon length (bp) | Tm (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|

| GAPDH | F: ACCACAGTCCATGCCATCAC | 452 | 91 |

| R: TCCACCACCCTGTTGCTGT | |||

| IL1-β | F: ATGGCAACTGTTCCTGAACTCAACT | 563 | 88 |

| R: CAGGACAGGTATAGATTCTTTCCTTT | |||

| IL-10 | F: ATGCAGGACTTTAAGGGTTACTTGGGTT | 455 | 88 |

| R: ATTTCGGAGAGAGGTACAAACGAGGTTT | |||

| IL-12/IL-23 | F: CAGAAGCTAACCATCTCCTGGTTTG | 396 | 89 |

| p40 | R: CCGGAGTAATTTGGTGCTCCACAC | ||

| IL-18 | F: CAGACAACTTTGGCCGACTTCA | 496 | 85 |

| R: ACACAAACCCTCCCCACCTAACT | |||

| iNOS | F: CAGCTCCACAAGCTGGCTCG | 657 | 91 |

| R: CAGGATGTCCTGAACGTAGACCTTG | |||

| TGF-β | F: GACCGCAACAACGCCATCTA | 236 | 88 |

| R: GGCGTATCAGTGGGGGTCAG | |||

| TNF-α | F: GAGCCCCCAGTCTGTGTCCTTCTA | 692 | 91 |

| R: CCCCGGCCTTCCAAATAAATACAT |

Cytokine detection by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

Supernatants from 24 hpi infected BMDM were collected, filtered through 0·22 µm filter and frozen at −70°C until used. IL-1β and TNF-α were quantified by ELISA using a commercial kit (Amersham).

Statistical analysis was performed using Student's t-test.

Results

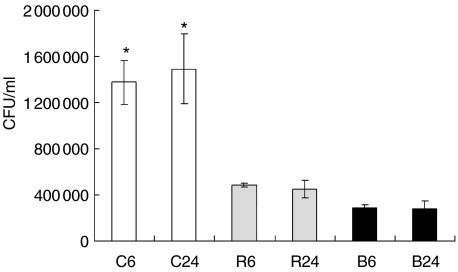

It has been shown that different genotypes of the Mtb complex induce a different outcome during in vivo infection of mice. To address whether this outcome could be related with bacterial phagocytosis, we evaluated the ability of BMDM to ingest three different strains of Mtb complex (Fig. 1). We observed that BMDM ingested four times more bacteria of the Canetti genotype in relation to the two other genotypes. These bacteria did not replicate intracelullarly during the evaluated times of infection (24 hpi).

Fig. 1.

Evaluation of intracellular mycobacteria in bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDM) infected with different Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) genotypes. Colony forming units (CFU) were determined at 6 and 24 h post-infection (hpi) in BMDM infected with three different strains of Mtb complex. Data from one representative experiment of four with similar data are represented. C: M. canetti (open bars), R: Mtb H37Rv (grey bars), B: Mtb Beijing genotype (black bars). *P < 0·05 Canetti in relation to other strains.

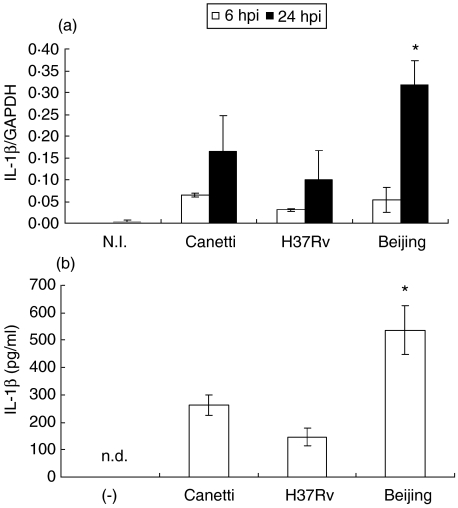

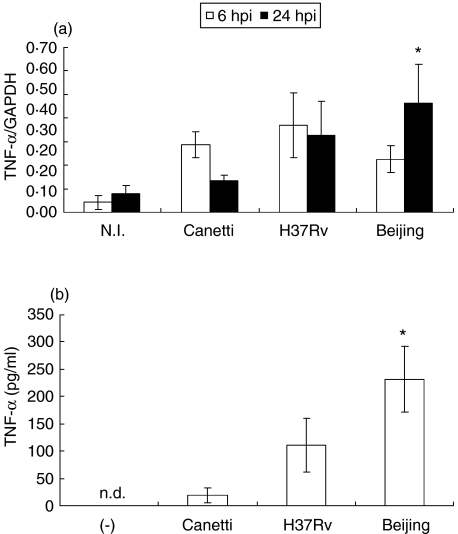

We next examined the expression of proinflammatory cytokine IL-1β at 6 and 24 hpi (Fig. 2). An increase in mRNA expression was observed at 6 hpi in BMDM infected with the three strains; however, at 24 hpi the highest expression was observed in cells infected with bacteria of the Beijing genotype (P = 0·033). To confirm that mRNA expression of IL-1β was related to protein levels, the presence of IL-1β was evaluated by ELISA in culture supernatants of BMDM that had been infected with the three mycobacterial strains. We observed a similar behaviour in cytokine expression (Fig. 2b) A similar expression pattern was observed with the proinflammatory cytokine TNF-α (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Interleukin (IL)-1β expression in bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDM) infected with different strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) complex. (a) mRNA expression of interleukin (IL)-1β at 6 h post-infection (hpi) (open bars) and 24 hpi (closed bars). (b) IL-1β production in supernatant of BMDM infected with different strains of Mtb complex at 24 hpi. Data from one representative experiment of four with similar data are represented. NI: not infected; n.d. not detected. *P < 0·05 Beijing 24 hpi in relation to Canetti 24 hpi.

Fig. 3.

Tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α expression in bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDM) infected with different strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) complex. (a) mRNA expression of TNF-α at 6 h post-infection (hpi) (open bars) and 24 hpi (closed bars). (b) TNF-α production in supernatant of BMDM infected with different strains of Mtb complex at 24 hpi. Data from one representative experiment of four with similar data are represented. NI: not infected; n.d. not detected. *P < 0·05 Beijing 24 hpi in relation to Canetti 24 hpi.

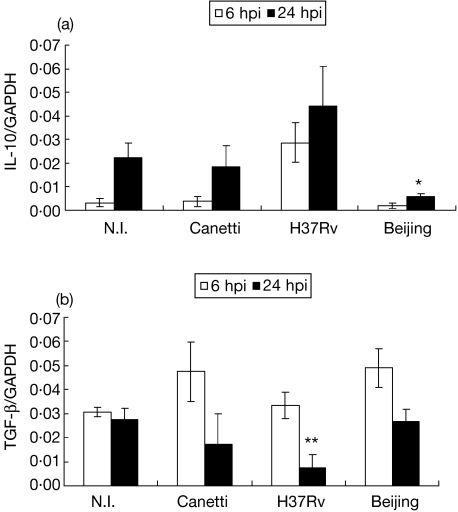

Immunoregulatory cytokines, such as IL-10 and TGF-β, were also analysed (Fig. 4). Regarding IL-10 mRNA expression, BMDM infected with the Mtb H37Rv strain showed an increase at 6 hpi that was maintained at 24 hpi. Cells infected with the Canetti strain showed a similar behaviour to the non-infected cells. Most interesting was the fact that cells infected with the Beijing strain abolished IL-10 expression in relation to non-infected cells and to those infected with H37Rv (P = 0·046). Regarding TGF-β, at 6 hpi cells infected with the Beijing genotype showed a temporary increase in mRNA expression (P = 0·02), which dropped at 24 hpi. At this time, macrophages infected with the H37Rv strain showed a diminished TGF-β expression in relation to non-infected BMDM and to those infected with bacteria of the Beijing genotype (P = 0·02).

Fig. 4.

mRNA expression of immunoregulatory cytokines in bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDM) infected with different strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) complex. (a) mRNA expression of interleukin (IL)-10 at 6 h post-infection (hpi) (open bars) and 24 hpi (closed bars). (b) mRNA expression of TGF-β at 6 hpi (open bars) and 24 hpi (closed bars). Data from one representative experiment of four with similar data are represented. NI: not infected. *P < 0·05. Beijing 24 hpi in relation to NI and H37Rv 24 hpi. **P < 0·05 H37Rv 24 hpi in relation to NI and Beijing 24 hpi.

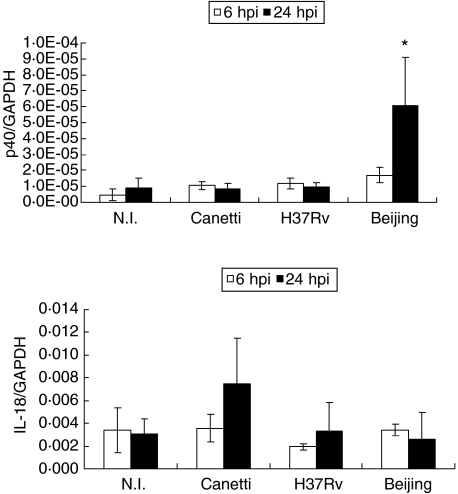

Because IL-12, IL-23 and IL-18 promote IFN-γ synthesis by T lymphocytes, mRNA expression for these cytokines was analysed (Fig. 5). p40 IL-12/IL-23 showed the highest increase in expression when BMDM were infected with the Beijing genotype at 24 hpi (P = 0·042); however, IL-18 did not change its expression at any time tested with any of the other infecting bacteria.

Fig. 5.

mRNA expression of cytokines that induce interferon (IFN)-γ expression in bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDM) infected with different strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) complex. (a) mRNA expression of p40 IL-12/IL-23 at 6 h post-infection (hpi) (open bars) and 24 hpi (closed bars). (b) mRNA expression of IL-18 at 6 hpi (open bars) and 24 hpi (closed bars). Data from one representative experiment of four with similar data are represented. NI: not infected. *P < 0·05. Beijing 24 hpi in relation to other conditions tested.

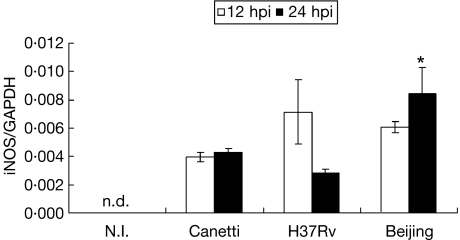

Because it has been shown that iNOS expression is essential to control murine pulmonary tuberculosis in vivo, mRNA expression was analysed (Fig. 6). At 6 hpi, iNOS mRNA expression was not detected under any of the conditions tested (not shown). Therefore, an extra time-point was included (12 hpi). At this time, all strains induced iNOS mRNA expression in similar quantities, but at 24 hpi BMDM infected with the Beijing genotype showed the highest level of iNOS mRNA (P = 0·022).

Fig. 6.

mRNA expression of iNOS in bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDM) infected with different strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) complex. mRNA expression of iNOS at 12 h post-infection (hpi) (open bars) and 24 hpi (closed bars). Data from one representative experiment of four with similar data are represented. NI: not infected. n.d. not detected. *P < 0·05. Beijing 24 hpi in relation to Canetti and H37Rv 24 hpi.

Discussion

The role played by different Mtb genotypes in the development of tuberculosis in the host has been analysed recently in vivo[10]. Besides the well-studied host factors such as MHC or NRAMP, one interesting result from this study was that development of the infection process clearly depends on the genotype of infecting bacteria. Strains with increased virulence have been identified in this way, such as HN878 [9] and those belonging to the Beijing genotype [10], which induce high mortality in infected mice in comparison to other strains. The way in which these Mtb genotypes determine the outcome of the disease in vivo has been related to the ability of each genotype to regulate the expression of cytokines that are essential for the development of an efficient immune response. Because the expression of cytokines is regulated by multiple, and sometimes unknown factors, we analysed separately the ability of each genotype, with a different virulence, to modify the cytokine expression in macrophages infected in vitro.

Results showed that each of the genotypes assessed had a different ability to induce different cytokines in infected BMDM, thus cells infected with the highly virulent Beijing genotype induced the highest increase in mRNA and protein expression of proinflammatory cytokines (IL-1β and TNF-α), mRNA of IL-12, which together with IL-18 promotes IFN-γ synthesis by T lymphocytes [13], and iNOS, which is essential for the production of NO and the control of mycobacterial infection [14]. Interestingly, IL-10 mRNA was diminished as compared to the other infected macrophages. This pattern of mRNA expression is interesting, as it suggests that macrophages infected with the high virulence Beijing genotype should promote a type I immunological response associated with control infection through production of IFN-γ by T cells [15,16].

Another remarkable observation was that cytokine expression was not realted with the number of intracellular bacteria; thus, on one hand, BMDM infected with M. canetti had the highest number of intracellular mycobacteria, but the lowest expression of proinflammatory cytokines whitout affecting expression of immunosuppressive cytokines; on the other hand, BMDM infected with the Beijing genotype had the lowest number of bacteria, but the highest expression of type I cytokines and low IL-10 levels.

It is interesting that, during in vivo studies, an early but ephemeral high expression of TNF-α and iNOS was seen during Beijing infection (days 1 and 3 postinfection). After 1 week of infection a pronounced drop of TNF-α and iNOS was produced, accompanied by low expression of IFN-γ[10], suggesting that lung macrophages were efficiently activated during the early phase of the infection, but were also rapidly deactivated. This in vivo result is consistent with our short-course in vitro study, which shows high expression of proinflammatory cytokines after 24 h of infection. However, the in vivo studies also showed a mild early IFN-γ expression, which is in disagreement with our in vitro results that showed high p40 IL-12/Il-23 and IL-18 expression. Thus, other unknown factors could be contributing to prevent appropriate Th-1 cell activation during Beijing infection. It is also important to consider that we used bone marrow-derived macrophages, which have significant maturation and physiological differences as compared to alveolar macrophages. It is likely that other cells can influence cytokine expression [17] and/or some mycobacterial components might also modify it, being expressed during this phase of infection [18,19].

One possibility whereby Mtb strains might modulate differential expression of cytokines and iNOS in BMDM could be through bacterial components interacting with macrophage receptors. For instance, it has been observed that purified lipids from different strains induce a differential pattern of cytokines [8]. In fact, a recent work shows that a phenolic glycolipid from hypervirulent strains has the ability to differentially regulate cytokine expression [20]. One interesting finding is that this lipid has the ability to diminish cytokine levels of proinflammatory cytokines. Another work from the same group [21] shows that mycobacteria from the Beijing genotype besides inducing low levels of these cytokines induce high levels of IL-4 and IL-13. These results are in disagreement with our findings. One posible explanation for these differences could be related to the nature of the strains used during the investigations; in fact, it has also been shown that different Beijing strains can induce a different responses in vivo[22]; thus, it could be expected that different strains of the Beijing genotype could induce a different pattern of cytokine expression.

It is important to note that strains from the Beijing genotype, beside their ability to generate resistance to drugs used to control the disease, have been studied recently because of their global distribution, finding them in regions of Asia, Central Europe and the USA [23]. Thus, we believe it is important to start to analyse the potential mechanisms by which this pathogen interacts with the host in order to develop more effective vaccines.

In conclusion, we found induction of type I cytokines and iNOS in macrophages infected with the Beijing genotype, accompanied by an interesting decrease in IL-10 mRNA. During in vivo infection, this is likely to be modified by other factors, identifying these factors will be an important issue to clarify the pathogenesis induced by this highly virulent and frequently fatal genotype.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by CONACYT grant number 31612-N. SEP and IEG are recipients of EDI, EDD, and COFAA.

References

- 1.Bellamy R, Ruwende C, Corrah T, McAdam K, Whittle HC, Hill A. Variations in the nramp1 gene and susceptibility to tuberculosis in West Africans. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:640–4. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199803053381002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bothamley GH, Swanson J, Schreuder G, et al. Association of tuberculosis and M. tuberculosis-specific antibody levels with HLA. J Infect Dis. 1989;159:549–55. doi: 10.1093/infdis/159.3.549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ben-Ali M, Barbouche MR, Bousnia S, Chabbou A, Dellagi K. Toll-like receptor 2 Arg677Trp polymorphism is associated with susceptibility to tuberculosis in Tunisian patients. Clin Diag Laboratory Immunol. 2004;11:625–6. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.11.3.625-626.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bellamy R, Ruwende C, Corrah T, et al. Tuberculosis and chronic hepatitis B virus infection in Africans and variation in the vitamin D receptor gene. J Infect Dis. 1999;179:721–4. doi: 10.1086/314614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Newport MJ, Huxley CM, Huston S, et al. A mutation in the interferon-γ-receptor gene and susceptibility to mycobacterial infection. N Eng J Med. 1996;335:1941–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199612263352602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Altare F, Durandy A, Lammas D, et al. Impairement of mycobacterial immunity in human interleukin-12 receptor deficiency. Science. 1998;280:1432–5. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5368.1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Jong R, Altare F, Haagen IA, et al. Severe mycobacterial and Salmonella infections in interleukin-12 receptor-deficient patients. Science. 1998;280:1435–8. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5368.1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Manca C, Tsenova L, Barry CE, III, et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis CDC1551 induces a more vigorous host response in vivo and in vitro, but is not more virulent than other clinical isolates. J Immunol. 1999;162:6740–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Manca C, Tsenova L, Bergtold A, et al. Virulence of a Mycobacterium tuberculosis clinical isolate in mice is determined by failure to induce Th1 type immunity and is associated with induction of IFN-α/β. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:5752–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.091096998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.López B, Aguilar D, Orozco H, et al. A marked difference in pathogenesis and immune response induced by different Mycobacterium tuberculosis genotypes. Clin Exp Immunol. 2003;133:30–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2003.02171.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Molodell M, Munder PG. Macrophage mediated tumor cell destruction measured by an alkaline phosphatase assay. J Immunol Meth. 1994;174:203–8. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(94)90023-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ramos-Payán R, Aguilar-Medina M, Estrada-Parra S, et al. Quantification of cytokine gene expression using an economical real-time polymerase chain reaction method based on SYBR Green I. Scand J Immunol. 2003;57:439–45. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.2003.01250.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Okamura H, Kashiwamura SI, Tsutsui H, Yoshimoto T, Nakanishi K. Regulation of interferon-γ production by IL-12 and IL-18. Curr Opin Immunol. 1998;10:259–64. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(98)80163-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.MacMicking JD, North RJ, LaCourse R, Mudgett JS, Shah SK, Nathan CF. Identification of nitric oxide synthase as a protective locus against tuberculosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:5243–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.10.5243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cooper AM, Dalton DK, Stewart TA, Griffin JP, Russell DG, Orme IM. Disseminated tuberculosis in interferon γ gene-disrupted mice. J Exp Med. 1993;178:2243–7. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.6.2243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Flynn JL, Chan J, Triebold KJ, Dalton DK, Stewart TA, Bloom BR. An essential role for interferon γ in resistance to Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. J Exp Med. 1993;178:2249–54. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.6.2249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Giacomini E, Iona E, Ferroni L, et al. Infection of human macrophages and dendritic cells with Mycobacterium tuberculosis induces a differential cytokine gene expression that modulates T cell response. J Immunol. 2001;166:7033–41. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.12.7033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Natarajan K, Latchumanan VK, Singh B, Singh S, Sharma P. Down-regulation of T helper 1 response to mycobacterial antigens due to maturation of dendritic cells by 10-kDa Mycobacterium tuberculosis secretory antigen. J Infect Dis. 2003;187:914–28. doi: 10.1086/368173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Detanico T, Rodrigues L, Sabritto AC, et al. Mycobacterial heat shock protein 70 induces interleukin-10 production: immunomodulation of synovial cell cytokine profile and dendritic cell maturation. Clin Exp Immunol. 2004;135:336–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2004.02351.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reed MB, Domenech P, Manca C, et al. A glycolipid of hypervirulent tuberculosis strains that inhibits the innate immune response. Nature. 2004;431:84–7. doi: 10.1038/nature02837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Manca C, Reed MB, Freeman S, et al. Differential monocyte activation underlies strain-specific Mycobacterium tuberculosis pathogenesis. Infect Immun. 2004;72:5511–4. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.9.5511-5514.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dormans J, Burger M, Aguilar D, et al. Correlation of virulence, lung pathology, bacterial load and delayed type hypersensitivity responses after infection with different Mycobacterium tuberculosis genotypes in a BALB/c mouse model. Clin Exp Immunol. 2004;137:460–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2004.02551.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bifani PJ, Mathema B, Kurepina NE, Kreiswirth BN. Global dissemination of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis W-Beijing family strains. Trends Microbiol. 2002;10:45–52. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(01)02277-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]