Abstract

The Mycobacterium tuberculosis fadD26 mutant has impaired synthesis of phthiocerol dimycocerosates (DIM) and is attenuated in BALB/c mice. Survival analysis following direct intratracheal infection confirmed the attenuation: 60% survival at 4 months post-infection versus 100% mortality at 9 weeks post-infection with the wild-type strain. The fadD26 mutant induced less pneumonia and larger DTH reactions. It induced lower but progressive production of interferon (IFN)-γ, interleukin (IL)-4 and tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α. Used as a subcutaneous vaccine 60 days before intratracheal challenge with a hypervirulent strain of M. tuberculosis (Beijing code 9501000), the mutant induced a higher level of protection than did Bacille Calmette–Guérin (BCG). Seventy per cent of the mice vaccinated with the fadD26 mutant survived at 16 weeks after challenge compared to 30% of those vaccinated with BCG. Similarly, there was less tissue damage (pneumonia) and lower colony-forming units (CFU) in the mice vaccinated with the fadD26 mutant compared to the findings in mice vaccinated with BCG. These data suggest that DIM synthesis is important for the pathogenicity of M. tuberculosis, and that inactivation of DIM synthesis can increase the immunogenicity of live vaccines, and increase their ability to protect against tuberculosis.

Keywords: BCG vaccination, experimental tuberculosis, strain fadD26, tuberculosis vaccination

Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB) is still one of the leading causes of mortality throughout the world [1,2]. The HIV/AIDS pandemic, the deterioration in public health systems in developing countries and the emergence of multidrug resistance (MDR) forms of tuberculosis have contributed further to the pandemic. Although efficient chemotherapy exists, the use of several drugs for a long period of treatment is necessary, and this leads to significant problems in terms of compliance and drug resistance. Prophylactic vaccination with the attenuated strain of Mycobacterium bovis Bacille Calmette–Guérin (BCG) is used in most countries. BCG is effective against severe forms of childhood tuberculosis. However, its efficacy is limited against adult pulmonary disease [3]. Hence, new rationally constructed vaccine candidates are required.

New methods have facilitated genetic manipulation of M. tuberculosis[4,5]. These advances, in combination with the availability of the complete sequence of the genome of M. tuberculosis[6], have enabled the study of the contribution to virulence of individual genes [7,8]. One approach used to identify the genes required for pathogenicity of M. tuberculosis has been the construction mutants, which are then tested for attenuation. Studies using this functional genomic approach have led to the development of attenuated mutants, including auxotrophs with various degrees of attenuation and potential as vaccine candidates in animal models [9].

From a library of signature-tagged transposon mutants of M. tuberculosis, one strain was identified with the transposon insertion mapped at 583 base pairs (bp) after the putative start of the gene fadD26, where it effects transcription [7]. The fadD26 gene product resembles acyl-CoA synthases, which are enzymes required for the biosynthesis of phthiocerol dimycocerosates (DIMs). Thus, the fadD26 mutant of M. tuberculosis Mt103 is completely devoid of DIMs [7,8]. DIMs are one of the six families of long multi-methyl-branched fatty acids located in the cell envelope of M. tuberculosis[10]. They play an important role in the permeability of the cell envelope [11] and in pathogenicity, as these molecules protect mycobacteria against the toxic effect of nitric oxide (NO) [12].

Rationally attenuated, live replicating mutants of M. tuberculosis are potential vaccine candidates. The advantage of using attenuated M. tuberculosis strains is that they produce a large number of protective antigens, including those that are absent from BCG [13]. Thus, vaccination with live attenuated M. tuberculosis can induce a stronger and longer immune stimulation, conferring higher levels of protection against tuberculosis than BCG [14].

Here we describe the survival, pathology and immune responses of BALB/c mice infected with the M. tuberculosis fadD26 mutant strain. The immune response and histological lesions induced by the fadD26 mutant were compared with those induced by its parental strain M. tuberculosis MT103. In addition, the protective efficacy of the fadD26 mutant strain was compared to that of BCG, after challenge with a clinical isolate of M. tuberculosis (Beijing strain 9501000). This isolate was shown previously to be strikingly hypervirulent in BALB/c mice, and to some extent BCG protected from it [15].

Materials and methods

Growth of bacterial strains

M. tuberculosis Mt103 was isolated from an immunocompetent tuberculosis patient [16]. The mutant fadD26 strain (1A29) was obtained by random mutagenesis using MT103 as parental strain. Its transposon insertion was mapped 583 bp after the putative start of the gene fadD26[7]. The BCG strain used was M. bovis BCG Phipps. This BCG substrain was the most protective of 10 strains tested in our BALB/c model of progressive pulmonary tuberculosis (manuscript in preparation). The Beijing strain code 9501000 was donated by Dr D. Van Soolingen (RIVM, the Netherlands). Strains Mt103, fadD26 and Beijing were grown in Middlebrook 7H9 medium (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, MI, USA) supplemented with OADC (albumin, catalase, dextrose enrichment) (Difco Laboratories). After 1 month of culture, mycobacteria were harvested, adjusted to 2·5 × 105 bacteria in 100 µl phosphate buffered saline (PBS), aliquoted, and maintained at −70°C until used. Before use, bacteria were recounted and their viability checked.

Experimental model of progressive pulmonary tuberculosis in BALB/c mice

To induce pulmonary tuberculosis infection, 8-week-old BALB/c male mice were anaesthetized with 56 mg/kg Pentothal, applied intraperitoneally. The trachea was exposed via a small midline incision on the anterior neck and 2·5 × 105 of viable bacteria of M. tuberculosis MT103 or fadD26 mutant were injected in 100 µl PBS. The incision was then sutured with sterile silk and the mice were maintained in groups of five in cages fitted with micro-isolators connected to negative pressure [17,18]. All procedures were performed in a laminar flow cabinet in a biosafety level III facility. Twenty animals per group were left untouched and deaths during the experiment were recorded to construct survival curves. Animal work was performed in accordance with the Institutional Ethics Committee and the national regulations on Animal Care and Experimentation.

Preparation of lung tissue for histology and automated morphometry

Groups of 12 mice in two different experiments were killed by exsanguination at 1, 3, 7, 14, 21, 28, 60 and 120 days after intratracheal infection. For histological study, four lungs, right or left, were perfused with 10% formaldehyde dissolved in PBS via the trachea, immersed for 24 h in the same fixative, and embedded in paraffin. Sections, 5 µm thick, taken through the hilum were stained with haematoxylin and eosin. In these slides, the area (µm2) occupied by granulomas and the percentage of lung surface affected by pneumonia were determined using an automated image analyser (Q Win Leica, Milton Keynes, UK) [17,18].

Determination of colony-forming units (CFU) in infected lungs

Right or left lungs from four mice in two different experiments per each sacrifice time interval were used for colony counting. Lungs were homogenized with a Polytron (Kinematica, Luzern, Switzerland) in sterile 50 ml tubes containing 3 ml of isotonic saline. Four dilutions of each homogenate were spread onto duplicate plates containing Bacto Middlebrook 7H10 agar (Difco Laboratory code 0627-17-4, Difco Laboratories) enriched with OADC. The time for incubation and colony counting was 21 days [15].

Real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis of cytokines in lung homogenates

Total RNA was isolated from pulmonary cell suspensions. The lung was placed into 2 ml of RPMI medium containing 0·5 mg/ml collagenase type 2 (Worthington, NJ, USA) and incubated for 1 h at 37°C. It was then passed through a 70 µm cell sieve, crushed with a syringe plunger and rinsed with the medium. Cells were centrifuged, the supernatant was removed and red cells were eliminated with lysis buffer. After counting, 350 µl of RLT buffer (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, CA, USA) were added to 5 × 106 cells and RNA was extracted using the RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen Inc.), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Quality and quantity of RNA were evaluated through spectrophotometry (260/280) and on agarose gels. Reverse transcription of the mRNA was performed using 5 µg RNA, oligo-dt, and the Omniscript kit (Qiagen). Real-time PCR was performed using the 7500 real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, USA) and Quantitect SYBR Green Mastermix kit (Qiagen). Standard curves of quantified and diluted PCR product, as well as negative controls, were included in each PCR run. Specific primers were designed using the program Primer Express (Applied Biosystems, USA) for the following targets: glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (G3PDH): 5′-cattgtggaagggctcatga-3′, 5′-ggaaggccatgccagtgagc-3′, inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS): 5′-agcgaggagcaggtggaag-3′, 5′-catttcgctgtctccccaa-3′, tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α): 5′-tgtggcttcgacctctacctc-3′, 5′-gccgagaaaggctgcttg-3′, interferon gamma (IFN-γ): 5′-ggtgacatgaaaatcctgcag-3′, 5′-cctcaaacttggcaatactcatga-3′, and interleukin 4 (IL-4): 5′-cgtcctcacagcaacggaga-3′, 5′-gcagcttatcgatgaatccagg-3′. Cycling conditions used were: initial denaturation at 95°C for 15 min, followed by 40 cycles at 95°C for 20 s, 60°C for 20 s, 72°C for 34 s. Quantities of the specific mRNA in the sample were measured according to the corresponding gene specific standard. The mRNA copy number of each cytokine was related to 1 million copies of mRNA encoding the G3PDH gene.

Measurement of cutaneous delayed-type hypersensitivity

Culture filtrate was harvested from M. tuberculosis MT 103 grown as described above for 4–5 weeks. Then, culture filtrate antigens were precipitated with 45% (w/v) ammonium sulphate, washed and redissolved in PBS. For delayed-type hypersensitivity (DTH) measurement, each mouse received an injection of 20 µg of antigen in 40 µl PBS into the hind footpad. The footpad was measured with a precision micrometer before and 24 h after the antigen injection, as described previously [19]. Each data point represents the mean of eight mice.

Protection against M. tuberculosis Beijing-strain in BALB/c mice vaccinated with fadD26 mutant or BCG

Two different experiments were performed using 20 mice for each of three experimental groups. The first group was vaccinated subcutaneously at the base of the tail with one dose of 2500 live fadD26 bacilli. The second group was vaccinated with 8000 live BCG bacilli, and the third group received only the diluent. We used these vaccination doses because in preliminary experiments they were the most protective.

At 60 days post-vaccination, all mice were challenged by the intratracheal route with 2·5 × 105 CFU of M. tuberculosis Beijing-strain code 9501000. We selected this strain because it is highly virulent in this animal model, and BCG vaccination confers lower protection when BALB/c mice are challenged with this strain than with the laboratory strain H37Rv [15]. Levels of protection were determined by the quantification of CFU in lung homogenates and by automated morphometry. The latter quantified the lung surface affected by pneumonia and the granuloma size in square microns. Ten more animals per group were left untouched and deaths were recorded to construct survival curves.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis for survival curves was performed using Kaplan–Meier plots and Log Rank tests. Student's t-test was used to determine statistical significance of CFU, histopathology, cytokine expression and DTH responses. P < 0·05 was considered as significant.

Results

Survival, lung histopathology and bacillary loads in BALB/c mice infected by the intratracheal route with fadD26 mutant or its parental strain M. tuberculosis MT103

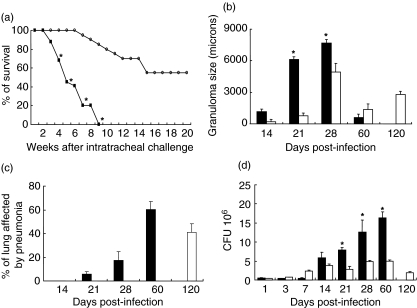

The residual virulence of the fadD26 mutant was studied previously by counting CFU in the lungs of BALB/c mice 3 weeks after intravenous (i.v.) infection [7]. Here we looked at the survival after intratracheal infection. Sixty per cent of animals infected with the fadD26 mutant strain survived after 4 months of infection. In contrast, mice inoculated with the wild-type M. tuberculosis MT103 started to die 3 weeks post-infection and all had died by 9 weeks (Fig. 1a).

Fig. 1.

Survival, pathology, and bacillary loads during lung infection with the fadD26 mutant or its parental strain MT103 in BALB/c mice. (a) All the mice (n=20) died 9 weeks after infection with MT 103 (black squares), whereas mice infected with the mutant (white squares) had 60% survival (P < 0·05). (b) The size of granulomas and the percentage of the lung occupied by pneumonia (c) in mice infected with MT103 (black bars) and or the fadD26 mutant (white bars). (d) Comparison of colony-forming units (CFU)/lung in mice infected with MT103 (black bars) or the fadD26 mutant (white bars). CFU and morphometry data are from four different animals at each time-point in two different experiments. Asterisks represent statistical significance (P < 0·05).

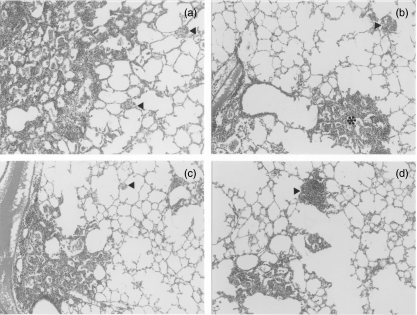

Histopathological analysis showed numerous granulomas in the lungs of mice infected with the M. tuberculosis MT103 strain as early as 14 days post-infection. These increased progressively in size, peaked at day 28 and then became smaller by day 60. Granumolas in the lungs of mice infected with the fadD26 mutant strain showed similar kinetics, but they were significantly smaller than those induced by MT103. Granulomas of intermediate size were seen very late, at day 120 post-infection (Figs 1b and 2). Progressive pneumonia was produced after 21 days post-infection with M. tuberculosis MT103, reaching its peak at day 60 when more than 60% of the lung surface was affected. By contrast, in mice infected with the fadD26 mutant these pneumonic areas were seen very late, at day 120 post-infection, and involved only 40% of the lung surface (Figs 1c and 2). These histopathological features correlated with the CFU in lung homogenates. During the first week of infection similar numbers of CFU were seen in both groups, whereas after days 14, 21, 28 and 60 post-infection significantly higher bacterial loads were seen in mice infected with MT103 than with the fadD26 mutant (Fig. 1c).

Fig. 2.

Representative histopathology of lungs from mice infected with the fadD26 mutant or with MT103, and from mice challenged with the Beijing strain after vaccination with the fadD26 mutant or with Bacille Calmette–Guérin (BCG). (a) Extensive pneumonia and small granulomas (arrowheads) 60 days after intratracheal infection with MT103. (b) Intermediate-sized pneumonic patches (asterisks) and granulomas (arrowheads) 120 days after infection with the fadD26 mutant. (c) 120 days after intratracheal challenge with Beijing strain, extensive pneumonia and small granulomas (arrowheads) were observed in mice vaccinated with BCG. (d) By contrast, 120 days after intratracheal challenge with the Beijing strain in mice vaccinated with the fadD26 mutant, there were smaller patches of pneumonia and bigger granulomas (arrowheads).

Immunological responses of mice infected with M. tuberculosis MT103 and the fadD26 mutant strain

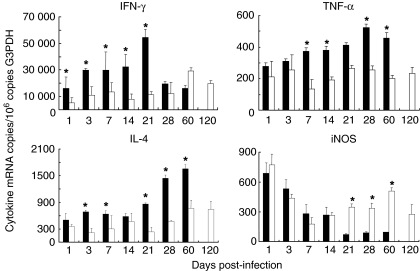

In agreement with the extensive lung inflammation produced by the MT103 strain, the expression of IFN-γ, IL-4 and TNF-α, determined by real-time reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) was higher in lungs from animals infected with MT103 than in lungs from mice infected with the fadD26 mutant (Fig. 3). The MT-103 strain induced a progressive increment in IFN-γ mRNA peaking at day 21, followed by a striking decrease at days 28 and 60. In contrast, the fadD26 mutant induced a progressive increase in IFN-γ expression, peaking at day 60, and 2 months later it had decreased by only 20% from its maximal level (Fig. 3). The MT-103 strain induced a stable expression of IL-4 from days 1–21 post-infection. Then, it increased 50% at day 28 and 100% at day 60, whereas fadD26 induced a significantly lower and stable IL-4 expression during the first month of infection, followed by an increase of 50% at days 60 and 120 (Fig. 3). The parental strain MT-103 induced a progressive increase in TNF-α expression, peaking at day 28, followed by a slight decrease at day 60, whereas the fadD26 mutant induced stable TNF-α expression, significantly lower than that induced by MT-103 after 1 week of infection (Fig. 3). MT103 induced a rapid and very high expression of iNOS, peaking at day 1. Then iNOS expression decreased progressively until day 60 post-infection. The fadD26 mutant induced similar iNOS expression as MT-103 during the first and second weeks post-infection. However, during late infection, the fadD26 mutant induced significantly higher iNOS expression than its parental strain (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Quantitative expression of mRNA encoding cytokines and nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) determined by real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) in lung homogenates from mice infected with the fadD26 mutant (white bars) or with its parental strain MT 103 (black bars). Bars represent the means and standard deviation from four different animals at each time point. Asterisks represent statistical significance (P < 0·05).

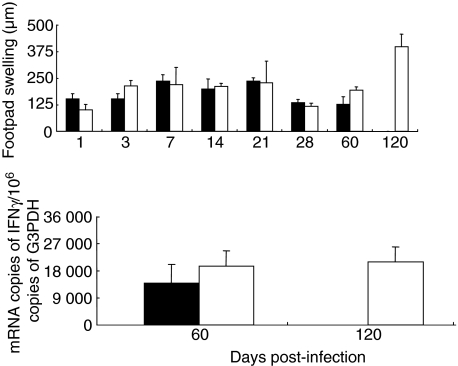

DTH reactions were assessed in four mice per time-point from each group in two different experiments, by measuring the skin inflammation following injection of culture filtrate antigens into the footpad (Fig. 4b). No significant differences were measured between both groups of animals until day 60 post-infection. Both strains induced progressively increasing DTH responsiveness until day 21. Then, at days 28 and 60, the DTH decreased. Interestingly, at day 120 post-infection, the DTH response in mice infected with the fadD26 mutant strain was the highest, suggesting that, at this very late time-point, there is a high cellular immune response against mycobacterial antigens (Fig. 4). We used real-time PCR to determine the constitutive expression of IFN-γ in the spleens at days 60 and 120 post-infection. At day 60, the spleens of animals infected with the fadD26 mutant contained non-significantly higher expression of IFN-γ than did spleens from mice infected with MT-103, maintaining similar IFN-γ expression at day 120 (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Upper panel: delayed hypersensitivity responses (DTH) to soluble antigens of M. tuberculosis in BALB/c mice infected with the MT103 strain (black bars) or with the fadD26 mutant (white bars). Similar DTH response kinetics were produced by both strains; the peak of DTH in mice infected with fadD26 mutant strain was at day 120. Lower panel: interferon gamma [interferon (IFN)-γ] expression in spleen determined by real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR).

Comparative protection from M. tuberculosis Beijing-strain in BALB/c mice vaccinated with the fadD26 mutant or with BCG

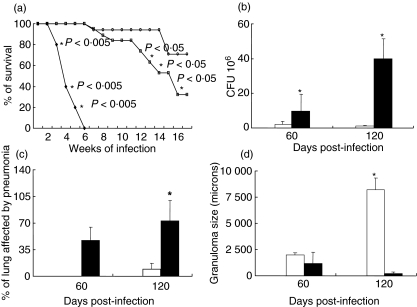

After intratracheal challenge with the hypervirulent M. tuberculosis strain Beijing 9501000, non-vaccinated control animals started to die after 4 weeks. After 6 weeks all control animals had died. By contrast, mice vaccinated with BCG showed 30% survival 4 months post-challenge, whereas 70% of the animals vaccinated with the fadD26 mutant survived at this time-point (Fig. 5a).

Fig. 5.

Survival, lung colony-forming units (CFU) and histopathology after intratracheal challenge with the Beijing strain in BALB/c mice vaccinated with the fadD26 mutant or with Bacille Calmette–Guérin (BCG). (a) Control non-vaccinated mice died after 6 weeks of infection (black squares), whereas 30% and 70% survival was observed 120 days after the challenge in mice vaccinated with BCG (white squares) and the fadD26 mutant (white circles), respectively. The P-values are indicated on the figure. (b) Mice vaccinated with the fadD26 mutant (white bars) developed significantly lower CFU than did BCG-vaccinated animals (black bars) at days 60 and 120 after challenge. (c) BCG vaccinated mice developed extensive pneumonia (black bars), whereas scarce pneumonic patches were observed in mice vaccinated with the fadD26 mutant (white bars). Asterisks represent statistical significance (P < 0·05). (d) Mice vaccinated with the fadD26 mutant (white bars) showed bigger granulomas than did BCG-vaccinated mice (black bars).

These survival results were in agreement with lung CFU determinations (Fig. 5b). Sixty days after intratracheal challenge, mice vaccinated with the fadD26 mutant showed five times lower CFU than did mice vaccinated with BCG (P < 0·05). More striking results were observed at day 120. Animals vaccinated with the fadD26 mutant showed 20 times lower CFU than did BCG vaccinated mice. Moreover, in this group less than 5% of the lung surface was affected by pneumonia and the granulomas were 40-fold larger (Fig. 5b, c, d). These results are important, because in this animal model the extension of pneumonia correlates with disease severity, whereas granuloma size correlates with protection [19].

Discussion

One of the most distinctive characteristics of M. tuberculosis is the high lipid content of its cell envelope, constituting up to 40% of its dry weight [20]. Several unique complex lipids of the cell wall, such as DIMs, are produced by the combined action of fatty acid synthases and polyketide synthases (PKS). The fadD26 protein synthesizes acyl-adenylates of long-chain fatty acids. In this way, these fatty acids are activated and transferred to the cognate PKS proteins permitting subsequent extension, incorporation and production of DIMs [21]. DIMs are physiologically important molecules for mycobacteria because they are involved in cell wall permeability [11] and in virulence [7,12,22]. The aim of the present study was, first, to extend the observations about the role of fadD26 in virulence and immunogenicity using a well-characterized model of progressive pulmonary tuberculosis in BALB/c mice, and then to test the fadD26 mutant as vaccine candidate.

M. tuberculosis can stimulate macrophages to produce NO and oxygen free radicals [23,24]. Indeed, these compounds have been related to the mycobactericidal activity of these cells. In comparison with the MT103 strain, mice infected with the fadD26 mutant showed significantly lower CFU at day 21 post-infection, in co-existence with significant higher iNOS expression. Previous in vitro observations showed that the fadD26 mutant is more susceptible to reactive nitrogen intermediates than its parental strain MT103 [12]. Our results showed that the fadD26 mutant is also more efficient than its parental strain at inducing iNOS expression.

Because MT103 produced progressive disease with more inflammation than did the fadD26 mutant, the expression of IFN-γ, IL-4 and TNF-α was higher in the lungs of mice infected with the parental strain. However, the kinetics of cytokine expression were broadly similar in both strains. MT103 evoked a rapid increase in IFN-γ expression during the second and third weeks of infection, whereas IL-4 expression was low. This phase was followed by a progressive decrease in IFN-γ expression and a twofold increase in IL-4 expression, with high CFU counts and extensive pneumonia. A similar trend in the pathology and immune response has been reported when BALB/c mice are infected with the laboratory strain H37Rv [17,18]. Thus, partial control of bacillary proliferation was produced while a Th-1 response was maintained. In contrast, the fadD26 mutant induced a lower but progressive increase in IFN-γ expression, peaking at day 60 post-infection, and maintaining its level of expression very late, at day 120 post-infection, together with pneumonic patches of moderate size affecting only 40% of the lung surface, and only four times more CFU than the original infecting dose. Thus, fadD26 has a significantly lower virulence than its parental strain, but it is not completely avirulent when a high dose is administered by the intratracheal route.

DTH reactions against culture filtrate antigens in mice infected with M. tuberculosis MT103 were comparable to those seen following infection with the fadD26 mutant. No significant differences were seen until 60 days after infection, but DTH in mice infected with the fadD26 mutant peaked at day 120 postinfection, implying that a long-lasting systemic cellular immune response was present at this very late time-point. Similarly, in the spleens of mice infected with the fadD26 mutant, constitutive expression of IFN-γ was relatively high at day 60 and almost undiminished at day 120. Thus, the immunological response to the M. tuberculosis fadD26 mutant is similar to that following infection with the parental strain, but is accompanied by less severe histological lesions and by longer-lasting cellular immune stimulation. These observations justify the use of fadD26 inactivation for the construction of live vaccines, because it fits well into the proposition that the aim of a ‘classical’ vaccine is to mimic natural infection as closely as possible without causing extensive disease [25].

Using this experimental model of progressive pulmonary tuberculosis in BALB/c mice, we recently studied the virulence and immunopathology induced by different M. tuberculosis genotypes [15]. We observed that three different strains, all distinctive members of the Beijing family, were hypervirulent, as they induced rapid death of mice with massive pneumonia and very high CFU counts. Moreover, when BCG vaccinated mice were challenged with the Beijing strain, the protection was lower than in mice challenged with the H37Rv strain. Hence, BCG protection depends also on the virulence of the infecting microorganism. For this reason, we used M. tuberculosis genotype Beijing in our vaccination experiments.

Interestingly, when the M. tuberculosis fadD26 mutant was used as vaccine and compared with BCG, it was clear that none of these vaccines prevented the establishment of infection, as indicated by the pathological changes and CFU determinations, but both protected against disease progression. The most striking result was the significantly increased 70% survival of mice vaccinated with the fadD26 mutant in comparison with the 30% survival conferred by BCG vaccination. This result confirms that BCG cannot efficiently prevent disease progression and death when the disease is produced by hypervirulent mycobacteria and, most importantly, that vaccination with the fadD26 mutant protects against progressive tuberculosis more efficiently than does BCG. The most significant decrease of lung CFU and tissue damage conferred by vaccination with the fadD26 mutant was observed 6 months after vaccination, confirming that stronger and longer protective immunity is produced by the fadD26 mutant than by BCG. These results extend the recent observation that another DIM mutant, erc, which synthesizes DIM but cannot transfer it to the cell wall, is also more efficient than BCG when used as a vaccine [14]. However, it is important to consider that our fadD26 mutant is not completely avirulent, so its use as vaccine will require further mutations to lower its virulence. Nevertheless, we consider that these results justify further studies of M. tuberculosis fadD26 mutants as potential vaccine candidates in other animal models.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by CONACyT (G36923 M). We thank Professor G. A. W. Rook for reading the manuscript and making helpful suggestions.

References

- 1.Dye C, Scheele S, Dolin P, Pathernia V, Raviglione MC WHO Global Surveillence Monitoring Project. Consensus statement: global burden of tuberculosis: estimated incidence, prevalence and mortality by country. JAMA. 1999;282:677–86. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.7.677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pablos-Mendez A, Raviglione MC, Laszlo A, et al. Global surveillance for antituberculosis drug resistance, 1994–97. World Health Organization–International Union against tuberculosis and lung disease. Working group on anti-tuberculosis drug resistance-surveillance. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:537–44. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199806043382301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fine PE. Variation in protection by BCG: implications for heterologous immunity. Lancet. 1995;346:1339–45. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)92348-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bardarov S, Kriakov J, Carriere C, et al. Conditionally replicating mycobacteriophages: a system for transcriptase delivery to Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:10965–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.20.10961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pelicic V, Jackson M, Reyrat JM, Jacobs WR, Gicquel B, Guilhot C. Efficient allelic exchange and transposon mutagenesis in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:10955–60. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.20.10955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cole ST, Brosch R, Parkhill J, et al. Deciphering the biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from the complete genome sequence. Nature. 1998;393:537–44. doi: 10.1038/31159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Camacho LR, Emsergueix D, Perez E, Gicquel B, Guilhot C. Identification of a virulence gene cluster of Mycobacterioum tuberculosis by signature tagged transposon mutagenesis. Mol Microbiol. 1999;34:257–67. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01593.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cox JS, Chen B, McNeil M, Jacobs WR. Complex lipid determines tissue specific replication of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in mice. Nature. 1999;402:79–83. doi: 10.1038/47042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith DA, Parish T, Stoker NG, Bancroft GJ. Characterization of auxotrophic mutants of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and their potential as vaccine candidates. Infect Immun. 2001;69:1142–50. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.2.1142-1150.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Daffè M, Lanèelle MA. Distribution of phthiocerol diester, phenolic mycosides and related compounds in mycobacteria. J Gen Microbiol. 1988;134:2049–55. doi: 10.1099/00221287-134-7-2049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Camacho LR, Constant P, Raynaud C, Lanèelle MA, Triccas JA, Gicquel B. Analysis of the phthiocerol dimycocerosate locus of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Evidence that this lipid is involved in the cell wall permeability. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:19845–54. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100662200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rousseau C, Winter N, Pivert E, et al. Production of phthiocerol dimycocerosates protects Mycobacterium tuberculosis from the cidal activity of reactive nitrogen intermediates produced by macrophages and modulates the early immune response to infection. Cell Microbiol. 2004;6:277–87. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2004.00368.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Behr MA, Wilson MA, Gill WP, Small P. Comparative genomics of BCG vaccines by whole-genome DNA microarray. Science. 1999;284:1520–3. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5419.1520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pinto R, Saunders BM, Camacho LR, Warwick J, Gicquel B, Triccas J. Mycobacterium tuberculosis defective in phthiocerol dimycocerosate translocation provides greater protective immunity against tuberculosis than the existing bacilli Calmette–Guérin vaccine. J Infect Dis. 2004;189:105–12. doi: 10.1086/380413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lòpez B, Aguilar LD, Orozco H, et al. A marked difference in pathogenesis and immune response induced by different Mycobacterium tuberculosis genotypes. Clin Exp Immunol. 2003;133:30–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2003.02171.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jackson M, Phalen SW, Lagranderie M. Persistence and protective efficacy of a Mycobacterium tuberculosis auxotroph vaccine. Infect Immun. 1999;67:2867–73. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.6.2867-2873.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hernández Pando R, Orozco EH, Sampieri A, et al. Correlation between the kinetics of Th1/Th2 cells and pathology in a murine model of experimental pulmonary pathology. Immunology. 1996;89:26–33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hernández Pando R, Orozco EH, Arriaga K, Sampieri A, Larriva SJ, Madrid MV. Analysis of the local kinetics and localization of interleukin 1 alpha, tumor necrosis factor alpha and transforming growth factor beta, during the course of experimental pulmonary tuberculosis. Immunology. 1997;90:507–16. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1997.00193.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hernández Pando R, Pavón L, Arriaga K, Orozco EH, Madrid MV, Rook GAW. Pathogenesis of tuberculosis in mice exposed to low and high doses of an environmental mycobacterial saprophyte before infection. Infect Immun. 1997;6:84–90. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.8.3317-3327.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Andersen R. The chemistry of lipids of tubercle bacilli. Harvey Lect. 1940;35:271–313. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Trivedl OA, Arora P, Sridharan V, Tickoo R, Mohanty D, Gokhale R. Enzymic activation and transfer of fatty acids as acyl-adenylates in mycobacteria. Nature. 2004;428:441–5. doi: 10.1038/nature02384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goren MB, Brokl O, Schaefer WB. Lipids of putative relevance to virulence in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Phthiocerol dimycocerosate and the attenuation indicator lipid. Infect Immune. 1974;9:150–8. doi: 10.1128/iai.9.1.150-158.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hernandez-Pando R, Schön T, Orozco EH, Serafín J, Estrada-Garcia I. Expression of nitric oxide synthase and nitrotyrosine during the evolution of experimental pulmonary tuberculosis. Exp Toxicol Pathol. 2001;53:257–65. doi: 10.1078/0940-2993-00182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chan X, Xing Y, Magliozzo RS, Bloom BR. Killing of virulent Mycobacterium tuberculosis by reactive nitrogen intermediates produced by activated macrophages. J Exp Med. 1992;175:1111–22. doi: 10.1084/jem.175.4.1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Young DB. Building a better tuberculosis vaccine. Nat Med. 2003;9:503–4. doi: 10.1038/nm868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]