Abstract

Recognition of repeat CpG motifs, which are common in bacterial, but not in mammalian, DNA, through Toll-like receptor (TLR)9 is an integral part of the innate immune system. As the role of TLR9 in the human gut is unknown, we determined the spectrum of TLR9 expression in normal and inflamed colon and examined how epithelial cells respond to specific TLR9 ligand stimulation. TLR9 expresssion was measured in human colonic mucosal biopsies, freshly isolated human colonic epithelial cells and HT-29 cells by reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction or Western blotting. Colonic epithelial cell cultures were stimulated with a synthetic CpG-oligodeoxynucleotide (ODN), exhibiting strong immunostimulatory effects in B cells. Interleukin (IL)-8 secretion was determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, nuclear factor-kappaB (NF-kB) activity by electrophoretic mobility shift assay and IkB phosphorylation by Western blotting. TLR9 mRNA was equally expressed in colonic mucosa from controls (n = 6) and patients with ulcerative colitis or Crohn's disease disease (n = 13). HT-29 cells expressed TLR9 mRNA and protein and responded to CpG-ODN (P < 0·01), but not to non-CpG-ODN stimulation, by secreting IL-8, apparently in the absence of NF-kB activation. Primary epithelial cells isolated from normal human colon expressed TLR9 mRNA, but were completely unresponsive to CpG-ODN stimulation in vitro. In conclusion, differentiated human colonic epithelial cells are unresponsive to TLR9 ligand stimulation in vitro despite spontaneous TLR9 gene expression. This suggests that the human epithelium is able to avoid inappropriate immune responses to luminal bacterial products through modulation of the TLR9 pathway.

Keywords: inflammatory bowel disease, interleukin-8, intestinal epithelial cell, oligonucleotides, Toll-like receptor

Introduction

Recognition of distinct microbial features and discrimination of potential harmful pathogens from ‘self’ is an integral part of the innate immune system. Innate immune responses are orchestrated by a variety of pattern-recognition receptors, most notably the Toll-like receptors (TLR) in humans [1–3]. The family of TLRs comprises at least 10 members, which recognize distinct pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), including lipoproteins (TLR2), dsRNA (TLR3), lipopolysaccharides (LPS) (TLR4) and flagellin (TLR5) [1,4,5]. Recently, a new member of the TLR family was identified and functionally characterized in mice. This new receptor, designated TLR9, recognizes specific bacterial DNA sequences characterized by a high content of unmethylated cytidine-phosphate-guanosine (CpG) motifs, which are prevalent in bacterial but not in mammalian genomic DNA [6]. Murine and human dendritic cells and B-cells express high levels of TLR9 and respond to bacterial DNA or stimulation with synthetic CpG oligodeoxynucleotides (ODN) in vitro[6–10]. Downstream signalling involves activation of a wide range of pathways, including nuclear factor-kappaB (NF-κB), leading to specific target gene activation and release of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines [2,6,11].

Although studies in cell lines and murine colitis models strongly suggest that TLRs, including TLR9, play a role in recognition and response to bacterial products in the gut, the experimental results are conflicting [12–14]. Some investigators have found that stimulation with bacterial DNA or synthetic CpG-ODNs induces a robust TLR9 mediated, proinflammatory cytokine response in cell lines and aggravates chemically induced colitis in rodents [14–16]. In contrast, others have shown that early administration of CpG-ODNs or probiotic bacterial DNA actually reduces the severity of experimental colitis [15,17–19]. It is possible that TLR9 signalling is also involved in immune responses in the human intestine and even play a role in the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease (i.e. ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease) [12,14,20], but this is currently unknown due to lack of human studies. Therefore, the primary aim of this study was to determine the spectrum of TLR9 expression in normal and inflamed human colonic mucosa. As the epithelium is known to play a key role in innate immune responses in the gut [21–25], we examined in more detail whether colonic epithelial cells express TLR9 and how they respond to synthetic TLR9 ligand stimulation in vitro.

Materials and methods

Patients

Permission for the study was obtained from the regional ethics committee and all participants gave informed written consent. Endoscopical biopsies were obtained from a total of 26 control patients (11 females/15 males, median age 46 years (range 23–82 years), which were referred to endoscopy for symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome or haematochezia, and had no endoscopical sign of inflammatory or malignant disease. Biopsy specimens were also obtained from a total of 15 patients with ulcerative colitis [nine females/six males, median age 44 years (range 31–82 years)] and 14 patients with Crohn's disease [eight females/six males, median age 37 years (range 21–76 years)]. Patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) had received no topical treatment or systemic corticosteroids within the past month or immunosuppressive drugs within the past 3 months, whereas oral 5-aminosalicylic acid was allowed. Stool cultures in all patients were negative for pathogens, including Clostridium difficile.

Biopsies

In control subjects, eight biopsy specimens were taken from the transverse or descending colon with radial jaw biopsies (Microvasive, Watertown, MA, USA) for reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) analysis and culture of primary colonic epithelial cells. In IBD patients, four to eight biopsy specimens were taken from the site of maximal inflammation (transverse, descending or sigmoid colon) and from areas, if any, with uninflamed mucosa (transverse or descending colon). Biopsies were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until total RNA was extracted. Biopsies used for isolation of primary epithelial colonic epithelial cells and lamina propria mononuclear cells (LPMNC) were collected in ice-cold Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) (Gibco, Paisley, UK).

Isolation of primary human colonic epithelial cells and LPMNC

Colonic epithelial cells were isolated from eight biopsies by use of ethylen-diaminetetra-acetic acid (EDTA)/ethylene glycol-bis(b-aminoethyl ether)-N,N,N,N′-tetra-acetic acid) (EGTA) for 10 min, providing mainly intact crypts and approximately 50% viable cells at 24 h as judged by 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) metabolism, vital staining and electron microscopy [26]. Total RNA for RT-PCR analysis was extracted from the cells with the Trizol LS Reagent (Invitrogen, Parsley, UK) immediately after isolation. Primary cell cultures were grown as monolayers in 96-well plates coated with bovine dermal collagen and in presence of ODNs (0·1–10 µg/ml) or a combination of tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α, interleukin (IL)-1β and interferon (IFN)-γ (all 10−8 M) for 18 h. After collection of culture medium (supernatant) for IL-8 analysis, MTT (0·25 mg/ml) (Sigma) was added and cell cultures were grown for another 4 h for assessment of viability [27]. LPMNCs were isolated from biopsy specimens after removal of the epithelial cells, as described previously [28]. Briefly, cell strainers containing tissue specimens were incubated overnight in the precense of 48 U/ml collagenase. LPMNC were then isolated by filtration and purification on a Lymphoprep gradient (Nycomed, Norway) [28], and RNA was extracted for TLR9 RT-PCR analysis as described above.

Human peripheral blood mononuclear cells

Human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), known to express TLR9 and respond to ODNs containing CpG motifs [7], were used as positive controls. Cells were isolated from buffy coats provided from healthy blood donors by use of a Ficoll Hypaque gradient (Lymphoprep; Axis-Shield POC AS, Oslo, Norway) [29]. RT-PCR for TLR9 was performed on isolated PBMCs as described below. In additional experiments, PBMCs were incubated at 37°C in the presence of ODN 2006 (1–10 µg/ml), ODN backbone (10 µg/ml), TNF-α, IL-1β and IFN-γ (all 10−9 M) and LPS (10 µg/ml). After a 60-min incubation period, cells were harvested and used for electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) and IκB Western blot analysis as described below.

Transformed human colonic cell lines

Three transformed human colonic epithelial cell lines, HT-29, CaCo-2 and DLD-1 were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD, USA); 1 × 105 cells were seeded in 96-well plates (NUNC, Naperville, IL, USA) coated with bovine dermal collagen (Cellon, in vitro A/S, Fredensborg, Denmark) and cultured in DMEM containing 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) (Gibco), 10 m m HEPES buffer (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA), 50 IU/ml penicillin, 50 µg/ml streptomycin and 0·5 mg/ml gentamycin (Gibco) at 37°C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 90% relative humidity. Cell line cultures were grown for 24 h to obtain subconfluency prior to stimulation.

RT-PCR analysis

Total RNA from whole colonic biopsies, freshly isolated colonic epithelial cells, LPMNC, PBMC, HT-29, CaCO-2 and DLD-1 cells were extracted with Trizol LS Reagent. The quality of RNA was verified by agarose gel electrophoresis of 0·5 µg total RNA from each sample. Samples containing degraded ribosomal RNA were discarded. Poly A RNA (mRNA) was purified from 20 µg total RNA pooled from colonic epithelial cells isolated from two patients by use of a Poly A Tract mRNA isolation system (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) and mRNA concentration was determined using RiboGreen RNA quantification kit (Molecular Probes, Oregon, USA). Complementary, single-stranded DNA (cDNA) was synthesized from 2 µg of total RNA or 0·5 µg Poly A using the first-strand cDNA synthesis kit (Amersham Bioscience, Hørsholm, Denmark). Oligo DNA primers were designed in VectorNTI (Informax, Frederick, MD, USA). Primers used for total RNA analysis were designed to span introns to distinguish the genomic sequence from RNA message (Table 1). The primers used in experiments based on isolated Poly A RNA also recognized genomic DNA, and amplification experiments without prior RT-reaction were included in all samples to exclude genomic DNA contamination. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as housekeeping gene control. PCR was performed in a thermal reactor (Eppendorf, Radiometer, Copenhagen, Denmark) and the RT-PCR products were gel purified and sequenced to confirm size and identity.

Table 1.

Specific polymerase chain reaction primers.

| Target mRNA | Forward primer | Reverse primer |

|---|---|---|

| TLR9 – Total RNA | TTCCTCTATTCTCTGAGCCG | GTAGGAAGGCAGGCAAGGTA |

| TLR9 – Poly A RNA | AAGGCCAAGGAGCTGCGAGA | AGGAAGTCCATAAAGGCCGC |

| GAPDH | GAGAATTCGAGTCAACGGAT | GCGAATTCGGTGCCATGGAA |

| TTGGTCGT | TTTGGCAT |

Western blot analysis for TLR9 protein and IκB

HT-29, isolated colonic epithelial cells and PBMCs were lysed in RIPA buffer (1% Nonidet, 0·25% Nadeoxycholat, 50 mM Tris HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 1 m M Na-fluoride, 1 mM Na-vanadate, 1 µ M phenylmethansulphonylfluoride (PMSF) and protease inhibitor cocktail) (Sigma) for 30 min on ice. After lysis, the samples were centrifuged at 15 000 g and the supernatants collected. Protein content was determined with the BCA reagent kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA). Cell lysate (30 µg) was loaded on precast 4–12% BT polyacrylamide gels (Invitrogen; Novex, San Diego, CA, USA) and submitted to electrophoresis at 200 V for 50 min, followed by transfer of proteins to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Amersham Biosiences, Bucks, UK). After transfer, the membranes were blocked in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) with 5% bovine serum albumine for 30 min at room temperature followed by repeated washing. The membranes were then incubated overnight at 4°C with either TLR9 monoclonal antibody (1 : 500) (Chemicon, Shelton, CT, USA), phospho-IκBα (Ser32/36) (5A5) (1 : 2000) or IκBα (112B2) monoclonal antibody (1 : 1000) (Cell Signalling Technology, Bervely, MA, USA), respectively, all diluted in TBS with 0·1% Tween-20 and 5% non-fat dry milk. After additional wash, membranes were incubated for 1 h with secondary HRP-linked antibody (Kierkegaard and Perry Laboratories, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) at room temperature. Finally, the membranes were developed with SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent substrate (Pierce) and images were recorded with a cooled CCD camera (Fuji Film).

Phosphorothioate linked oligodeoxynucleotide stimulation

All tested ODNs contained phosphorothioate backbones to ensure resistance to nuclease degradation [9,10]. The CpG ODN 2006 was selected due to its strong immunostimulatory activity in human B cells [7,30,31]. Phosphorothioate linked ODNs were synthesized at MWG Biotech (Ebersberg, Germany): CpG ODN 2006: tcgtcgttttgtcgttttgtcgt; non-CpG ODN 2006 (inverted version of ODN 2006): tgctg cttttgtgcttttgtgct; ODN-backbone: ccccccccccccccccccccccc (bold type represents CpG dinucleotides). In IL-8 and MTT experiments, cell cultures were stimulated with ODNs (0·1–10 µg/ml) for 5 and 24 h, respectively, with restimulation after 8 h. Cell medium (supernatant) was collected for IL-8 analysis and cell cultures were grown an additional 4 h in the presence of MTT (0·25 mg/ml) [27]. For NF-κB/IκB analyses, HT-29 cells were seeded in six-well plates (2 × 106 cells/well), cultured for 24 h and then stimulated with ODNs (0·1–10 µg/ml) for 60 min and for 5 h, respectively.

IL-8 analysis

IL-8 protein secretion was measured in cell culture supernatants by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (R&D, Abingdon, UK) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Measurements were performed in duplicate.

Preparation of cytosolic and nuclear extracts

ODN-stimulated HT-29 cells (2 × 106) or PBMCs (2 × 106) were homogenized in 500 µl ice-cold buffer H (10 m M HEPES-KOH (pH 7·9), 10 m M KCl, 0·1 m M EDTA, 0·1 m M EGTA, 0·75 m M spermidine, 0·15 m M spermine, 1 m M DTT, 1 m M PMSF and protease inhibitor cocktail 1 : 500) (Sigma) in a Dounce homogenizer with a B-type pestle. Five µl 10% NP40 was added and the homogenate was placed on ice for 10 min, then transferred to a tube, underlaid with 400 µl buffer H with 30% (w/v) sucrose, and centrifuged at 1200 g for 10 min. The nuclear pellet was resuspended in 100 µl buffer N (20 m M HEPES-KOH (pH 7·6) 20% (v/v) glycerol, 10% (w/v) sucrose, 420 m M KCl, 5 m M MgCl2, 0·1 m M EDTA, 1 m M DTT, 1 m M PMSF and protease inhibitor cocktail 1 : 500, incubated with rotation for 45 min at 4°C and finally centrifuged for 60 min at 20·000 g. The nuclear extracts were stored at −80°C until analysis. HT-29 cells stimulated with a combination of IL-1β/TNF-α/IFN-γ (all 10−9 M) were used as a positive control for activation of NF-κB.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) was performed by incubating 5 µg nuclear extract with 0·7 µg sonicated poly(dI:dC) (Amersham Bioscience), 1% polyethylene glycol 8000, 1 m M DTT, 7 m M MgCl2, 0·01% NP40 and 0·05 mM ZnCl2 in buffer D (20 m M HEPES-KOH (pH 7·9), 20% v/v glycerol, 0·2 m M EDTA, 0·1 M KCl 0·5 m M PMSF 1 m M (DTT) to a final volume of 9 µl, followed by the addition of 5 fmol 32P-labelled double-stranded oligonucleotide (specific activity 15 000 cpm/fmol). The samples were incubated at room temperature for 30 min and then loaded onto a prerun 4·5% acrylamide gel containing 1% glycerol, 0·01% CHAPS and 0·01% NP40 and run for 90 min at 300 V in 0·25 × TBE supplemented with 1% glycerol, 0·01% CHAPS and 0·01% NP40 at 4°C. Then the gel was fixed in 10% acetic acid/20% methanol/70% water for 15 min, dried under vacuum on Whatman 3M M paper, exposed to a phosphor imaging plate for 12 h and analysed on a phosphor imager (Fuji Film, Stockholm, Sweden).

Statistics

Results are presented as means (s.e.m.). Data were analysed by the Kruskal–Wallis test using Dunn's multiple comparison post-test and Wilcoxon's test for paired variables where appropriate (GraphPad Prism 4·0). Values of P < 0·05 (two-tailed) were considered significant.

Results

Expression of TLR9 in normal and inflamed human colonic mucosa

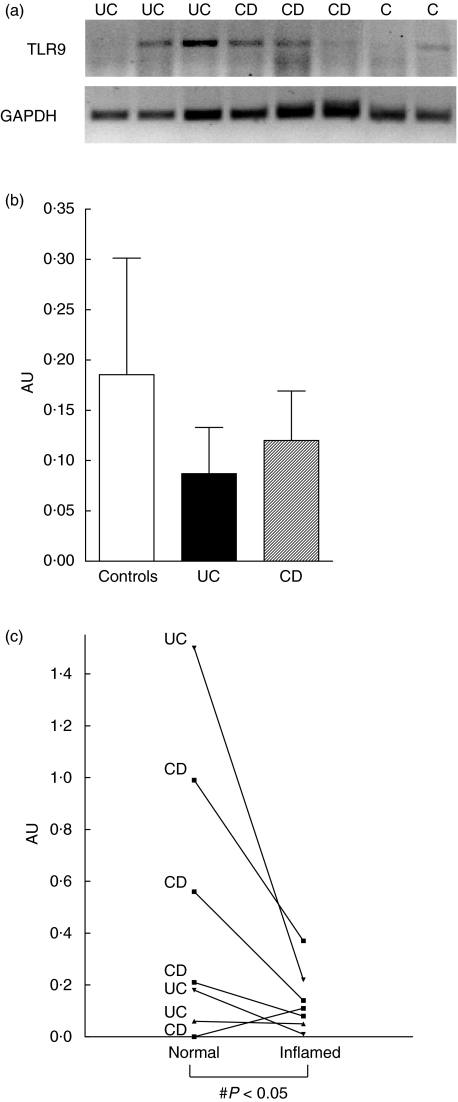

To evaluate whether TLR9 is present in human colon, we first examined TLR9 expression in whole biopsy specimens. As shown in Fig. 1a, TLR9 mRNA was detected by RT-PCR in mucosal biopsies from both control subjects and patients with ulcerative colitis or Crohn's disease. The TLR9 RT-PCR products were gel purified and sequenced to confirm size and identity. The figure shows an example of an original gel illustrating that the expression of TLR9 mRNA was variable, and in some cases undetectable, despite distinct expression of GAPDH. When the optical densities of the TLR9 bands were quantified relative to GAPDH in the entire material, no significant differences were observed between control subjects (n = 6) and patients with IBD (n = 13) (Fig. 1b). However, when a subset of patients served as their own control (n = 7), the level of TLR9 expression was significantly lower in samples from inflamed mucosa compared with those obtained in parallel from an endoscopically uninflamed area (Fig. 1c).

Fig. 1.

Expression of Toll-like receptor (TLR) 9 mRNA in human colonic mucosal biopsies. Reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) analysis of total RNA (2 µg) extracted from colonic biopsy specimens were performed as described in Material and methods. (a) Expression of TLR9 mRNA is shown in representative biopsies from control subjects (C) and patients with ulcerative colitis (UC) or Crohn's disease (CD). The identity of the TLR9 PCR products was confirmed by sequencing. Expression of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) is included as housekeeping gene control. (b) PCR products were semiquantified by densitometric scanning and expressed relative to GAPDH expression (arbitrary unit, AU). No significant differences were observed between controls, UC or CD patients (P = n.s.). Data from six to seven individual subjects in each group are included; bars represent means (s.e.m.) values. (c) Expression of TLR9 mRNA in paired biopsies obtained from inflamed and uninflamed colonic mucosa in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Figure presents data from three UC and four CD patients. ♯P < 0·05 compared to expression in uninflamed biopsies.

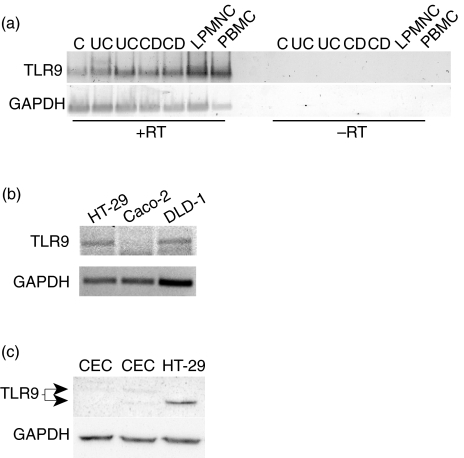

TLR9 expression in human colonic epithelial cells

To evaluate whether TLR9 is present in human colonic epithelium, RT-PCR analysis was performed on freshly isolated colonic epithelial cells and three established cell lines; HT-29, CaCo-2 and DLD-1. As shown in Fig. 2a (left), TLR9 mRNA was widely expressed in isolated human colonic epithelial cells from control subjects as well as patients with ulcerative colitis or Crohn's disease. No PCR products were present in samples run in parallel without the RT-reaction (Fig. 2a, right). TLR9 mRNA was also present in LPMNC isolated in parallel as well as in PBMC from healthy donors, which were included as a known positive control to confirm the specificity of primer and PCR analysis. Finally, we found that TLR9 mRNA was equally expressed in HT-29 cells and DLD-1 cells, but absent in Caco-2 cells (Fig. 2b).

Fig. 2.

Expression of TLR9 in freshly isolated human colonic epithelial cells and intestinal epithelial cell lines. (a) Expression of TLR9 mRNA was examined by reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) using isolated mRNA (0·5 µg) from colonic epithelial cells isolated from biopsies obtained of two control subjects (C) or two patients with ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn's disease (CD) (left panel). TLR9 mRNA expression in isolated lamina proria mononuclear cells (LPMNC) are included for comparison and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) as a known positive control. No PCR products were present in samples run in parallel without the RT-reaction (right panel). (b) Expression of TLR9 mRNA in HT29, CaCo2 and DLD-1 cells analysed by RT-PCR. Expression of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) is included as housekeeping gene control. (c) TLR9 protein expression was evaluated in freshly isolated human colonic epithelial cells (CEC) and HT-29 cells by Western blotting on cell lysates as described in Materials and methods. Two isofoms of the TLR9 protein are indicated. Western blotting of GAPDH was performed to confirm equal loading of protein on the gel. Data from one experiment out of two are presented.

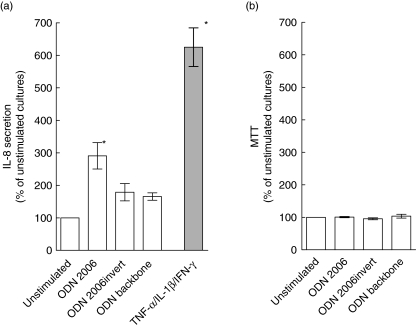

CpG-oligonucleotide effects on IL-8 secretion and viability in human colonic epithelial cells

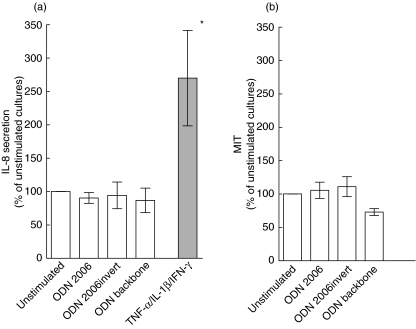

Initial functional experiments were carried out in HT-29 cells as these cells clearly expressed TLR9 protein (Fig. 2c) and are known to respond to immune stimulation by IL-8 protein secretion [32]. As shown in Fig. 3a, variance analysis revealed that stimulation with CpG ODN 2006 (10 µg/ml) caused a significant increase in IL-8 secretion relative to unstimulated cells. The inverted (non-CpG) version of ODN 2006 (10 µg/ml) and the phosphorothioate backbone ODN (10 µg/ml) also induced IL-8 secretion in HT-29 cells, but these changes were not significant (Fig. 3a). Higher concentration of CpG ODN 2006 (50 µg/ml) or prolonged exposure (24 h) caused no further changes in IL-8 secretion (data not shown). For comparison, stimulation with a combination of TNF-α, IL-1β and IFN-γ induced a marked, significant increase in IL-8 secretion as expected. Exposure of HT-29 cells to CpG ODN 2006 had no effect on viability as jugded by MTT metabolism (Fig. 3b). Higher concentrations of CpG ODN 2006 (50 µg/ml) and prolonged time of exposure (24 h; data not shown) or treatment with the inverted version of ODN 2006 or backbone ODN had no effect on viability of HT-29 cells.

Fig. 3.

Effects of oligodeoxynucleotides (ODN) on IL-8 secretion and viability in HT-29 cells. (a) IL-8 protein secretion in cell supernatants [measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)] after stimulation with CpG ODN 2006, non-CpG ODN 2006 (invert version) or ODN phosphorothioate backbone (10 µg/ml) for 5 h. For comparison, the response to mixed tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α, interleukin (IL)-1β and interferon (IFN)-γ (10−9 M) stimulation is also shown. IL-8-values in stimulated cultures are expressed relative to values in unstimulated cultures. (b) Viability in the ODN stimulated cultures assessed by 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) metabolism. MTT values in ODN-treated cultures are expressed relative to values in unstimulated cultures. *P < 0·01 compared to unstimulated cultures. Mean (s.e.m.) values of eight independent experiments are presented.

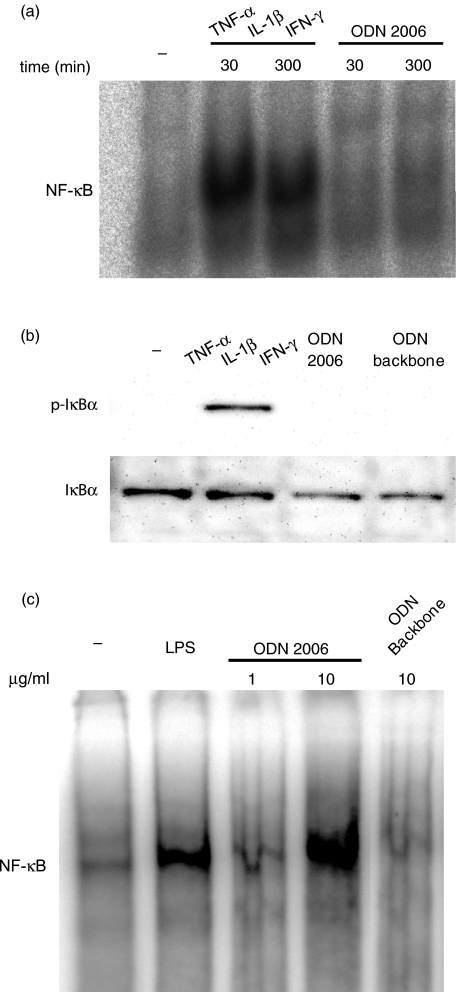

Effects of ODNs on NF-κB activation/IκB phosphorylation in HT-29 cells

Despite induction of IL-8 protein secretion, stimulation with CpG ODN 2006 (10 µg/ml) caused no clear activation of NF-κB in HT-29 cells. This finding was confirmed by the complete lack of IκB phosphorylation in response to stimulation with the ODN. For comparison, TNF-α/IL-1β/IFN-γ stimulation induced marked NFκB activation (Fig. 4a) and IκB phosphorylation (Fig. 4b) in HT-29 cells as expected. Human PBMC exposed to CpG ODN 2006 (1 and 10 µg/ml) (or LPS) showed a clear, concentration dependent activation of NF-κB (Fig. 4c), confiming the proinflammatory potential of the CpG oligo. Finally, PBMC stimulated with the backbone ODN were unresponsive.

Fig. 4.

Effects of oligodeoxynucleotides (ODN) on NF-κB activation/I-κB phosphorylation in human intestinal epithelial cells and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC). HT-29 cells were incubated with CpG ODN 2006, ODN phosphorothioate backbone (10 µg/ml) or tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α/interleukin (IL)-1β/interferon (IFN)-γ (all 10−9 M) for 30, 60 or 300 min. (a) NF-κB activity in nuclear extracts analysed by electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA). (b) IκB phosphorylation and total IκB expression measured in cell lysates by Western blotting. (c) Human PBMCs were isolated from buffy coats by Ficoll and incubated with CpG ODN 2006 (1–10 µg/ml), ODN phosphorothioate backbone (10 µg/ml) and lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (10 µg/ml) for 60 min. NF-κB activity in nuclear extracts was analysed by EMSA. Specificity of the bands was determined by cold competition. Representative data from one of three independent experiments are shown.

Effects of ODNs on primary human colonic epithelial cells

To extend the findings in HT-29 cells, we finally examined how primary human colonic epithelial cells responded to ligand stimulation. As shown in Fig. 5a, variance analysis revealed that exposure of primary colonic epithelial cell cultures to CpG ODN 2006 caused no increase in IL-8 secretion, whereas a clear response was observed following cytokine stimulation (Fig. 5a). Consistent with these findings, the two apparent TLR9 isoforms were only barely detecable in freshly isolated colonic epithelial cells as judged by Western blot analysis (Fig. 2c). Finally, CpG ODN exposure induced no significant change in viability in colonic epithelial cells as jugded by MTT metabolism (Fig. 5b).

Fig. 5.

Effects of oligonucleotides (ODN) on interleukin (IL)-8 secretion and viability in primary human colonic epithelial cells. (a) IL-8 protein secretion in cell supernatants assessed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) after stimulation with CpG ODN 2006, non-CpG ODN 2006 (invert version) or ODN phosphorothioate backbone (all 10 µg/ml) for 5 h. For comparison, the response to mixed tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α, interleukin (IL)-1β and interferon (IFN)-γ (10−8 M) stimulation is shown. IL-8 values in stimulated cultures are expressed relative to values in unstimulated cultures. (b) Cell viability in cultures assessed by the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay. MTT values in ODN-treated cultures are expressed relative to values in unstimulated cultures. *P < 0·05 compared to unstimulated cultures. Data represents mean (s.e.m.) values of six to eight independent experiments.

Discussion

In this study, we have shown that TLR9 mRNA is variably expressed in normal human colonic mucosa and in samples from patients with ulcerative colitis or Crohn's disease. Moreover, we observed that the average level of gene expression was markedly reduced in inflamed mucosa compared to normal gut, suggesting the existence of a down-regulatory mechanism that protects the inflamed mucosa from further TLR mediated injury. However, previous studies of other TLRs in inflammatory bowel disease mucosa have produced highly variable results, ranging from increased TLR4 expression to reduced or unchanged levels of TLR3 and TLR2, respectively [4,33,34]. Therefore, the expression of distinct members of TLRs seems to be differentially, rather than uniformly, regulated in inflamed intestinal mucosa [4,35,36].

To extend the intitial findings in intact biopsies, we examined next whether TLR9 is expressed in the colonic epithelium, as this represents an important frontline cellular component of the innate immune system in the gut [24,25,37]. Accordingly, we found that TLR9 mRNA was expressed spontaneously in freshly islolated colonic epithelial cells not only from controls [23], but also from patients with ulcerative colitis or Crohn's disease (Fig. 2a). This raised the question of whether these cells also have the full capacity to recognize and respond to specific TLR9 ligand stimulation. As the availability of primary colonic epithelial cells is limited, initial experiments were performed in HT-29 cells, which spontaneously express not only TLR9 mRNA [38], but also TLR9 protein (Fig. 2c). HT-29 cells showed a clear response to CpG ODN stimulation as measured by IL-8 secretion, and compared to the minor effect induced by a true non-CpG control ODN, our results suggest that HT-29 cells are able to distinguish between CpG ODNs mimicking bacterial DNA and non-CpG or backbone variants. Although IL-8 normally is considered a NFκB responsive gene [39], we were unable to detect NF-κB- or IκB activation in the CpG ODN-treated HT-29 cells, which actually resembles the findings in a previous study using Escherichia coli DNA stimulation [38]. The lack of response was not explained simply by the methodology used, as we were able to confirm that TLR9 positive mononuclear cells run in parallel responded to CpG ODN stimulation by NFκB activation, as described previously [6,10,19]. However, the CpG ODN-induced levels of IL-8 secretion in HT-29 cells were considerably lower than in the cytokine control experiments, and it is possible that the effect of CpG ODN stimulation is too small to induce a measureable NFκB activation signal [38]. A variety of other intracellular pathways have recently been implicated in TLR signalling in epithelial cells, including activator protein-1 (AP-1) or extracellular-regulated kinase (ERK) and protein kinase C (PKC) [21,38,40–43]. Therefore, another possible explanation for the lack of NFκB activation may be that TLR9 signalling in epithelial cells involves activation of alternative intracellular pathways, as also suggested previously [38].

Several studies have shown that transformed intestinal cell lines are not fully representative for the differentiated human colonic epithelium [27,44,45]. Therefore, a key element of the present study was to examine how primary colonic epithelial cells responded to CpG ODN stimulation. To achieve this objective, we used cells obtained from strictly normal colonic mucosa, as our initial gene expression studies showed lower levels in inflamed specimens (Fig. 1c). The immune stimulatory effect was measured by release of IL-8 protein, which seemed appropriate as judged from the initial cell line experiments and previous functional studies in primary cells [27,46]. While TLR9 mRNA was clearly identified in these cells, TLR9 protein was only weakly expressed. Consistent with this observation, CpG ODN stimulation completely failed to induce a significant increase in IL-8 protein secretion in normal primary colonic epithelial cells. Interestingly, at least five isoforms of TLR9 protein are now known (http://www.ebi.uniprot.org/index.shtml; Accession number Q9NR96) and it seemed that two of these isoforms were present in freshly isolated colonic epithelial cells, while only one isoform was seen in HT-29 cells. As the functional role of these different isoforms is unknown, further investigations are required to elucidate whether CpG ODN reponsiveness is correlated to the presence of distinct isoforms of TLR9 protein. Moreover, the immune stimulatory potential of various CpG ODNs is determined by structural properties, such as frequency and placement of CpG motifs, length of ODNs and composition of flanking nucleotides [9,10,47,48]. The CpG ODN tested in this study was chosen due to its proven ability to activate mononuclear cells, but it is possible that other CpG ODNs may exhibit a stronger immune stimulatory potential in primary colonic epithelial cells [7,10]. Finally, TLR2- and TLR4-mediated hyporesponsiveness to repeat ligand stimulation in epithelial cells has recently been shown to be regulated by Tollip, a Toll inhibitory protein that interferes with IL-1 receptor associated kinase (IRAK) [23,41,49]. We cannot exclude that a similar inhibitory mechanism is responsible for the differences in CpG ODN responsiveness observed between primary colonic epithelial cells, which are constantly exposed to the luminal bacterial flora prior to isolation, and HT-29 cells that are repeatedly passaged in a bacteria free environment.

In conclusion, we have shown that fully differentiated human colonic epithelial cells, unlike a commonly used cancer cell line, are completely unresponsive to TLR9 ligand stimulation in vitro despite spontaneous TLR9 gene expression. If similar mechanisms are operative in vivo, our results suggest that normal human colonic epithelium is able to avoid inappropriate innate immune responses to luminal bacterial DNA through modulation of the TLR9 pathway.

Acknowledgments

The technical assistance of Anne Hallander, Birgit Dejbjerg, Anni Petersen, Hanne Fulgsang and Vibeke Tuxen at the Laboratory of Gastroenterology 54-O3, Herlev University Hospital, Denmark is greatly appreciated.

References

- 1.Akira S, Hemmi H. Recognition of pathogen-associated molecular patterns by TLR family. Immunol Lett. 2003;85:85–95. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2478(02)00228-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aderem A, Ulevitch RJ. Toll-like receptors in the induction of the innate immune response. Nature. 2000;406:782–7. doi: 10.1038/35021228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Akira S, Takeda K, Kaisho T. Toll-like receptors: critical proteins linking innate and acquired immunity. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:675–80. doi: 10.1038/90609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cario E, Podolsky DK. Differential alteration in intestinal epithelial cell expression of Toll-like receptor 3 (TLR3) and TLR4 in inflammatory bowel disease. Infect Immun. 2000;68:7010–7. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.12.7010-7017.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Faure E, Thomas L, Xu H, Medvedev A, Equils O, Arditi M. Bacterial lipopolysaccharide and IFN-gamma induce Toll-like receptor 2 and Toll-like receptor 4 expression in human endothelial cells: role of NF-kappa B activation. J Immunol. 2001;166:2018–24. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.3.2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hemmi H, Takeuchi O, Kawai T, et al. A Toll-like receptor recognizes bacterial DNA. Nature. 2000;408:740–5. doi: 10.1038/35047123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hornung V, Rothenfusser S, Britsch S, et al. Quantitative expression of Toll-like receptor 1–10 mRNA in cellular subsets of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells and sensitivity to CpG oligodeoxynucleotides. J Immunol. 2002;168:4531–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.9.4531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Verthelyi D, Ishii KJ, Gursel M, Takeshita F, Klinman DM. Human peripheral blood cells differentially recognize and respond to two distinct CPG motifs. J Immunol. 2001;166:2372–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.4.2372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klinman DM, Takeshita F, Gursel I, et al. CpG DNA: recognition by and activation of monocytes. Microbes Infect. 2002;4:897–901. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(02)01614-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hartmann G, Krieg AM. Mechanism and function of a newly identified CpG DNA motif in human primary B cells. J Immunol. 2000;164:944–53. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.2.944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chu W, Gong X, Li Z, et al. DNA-PKcs is required for activation of innate immunity by immunostimulatory DNA. Cell. 2000;103:909–18. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00194-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rakoff-Nahoum S, Paglino J, Eslami-Varzaneh F, Edberg S, Medzhitov R. Recognition of commensal microflora by toll-like receptors is required for intestinal homeostasis. Cell. 2004;118:229–41. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Strober W, Fuss IJ, Nakamura K, Kitani A. Recent advances in the understanding of the induction and regulation of mucosal inflammation. J Gastroenterol. 2003;38(Suppl. 15):55–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Strober W. Epithelial cells pay a Toll for protection. Nat Med. 2004;10:898–900. doi: 10.1038/nm0904-898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Obermeier F, Dunger N, Deml L, Herfarth H, Scholmerich J, Falk W. CpG motifs of bacterial DNA exacerbate colitis of dextran sulfate sodium-treated mice. Eur J Immunol. 2002;32:2084–92. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200207)32:7<2084::AID-IMMU2084>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kobayashi M, Kweon MN, Kuwata H, et al. Toll-like receptor-dependent production of IL-12p40 causes chronic enterocolitis in myeloid cell-specific Stat3-deficient mice. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:1297–308. doi: 10.1172/JCI17085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Obermeier F, Dunger N, Strauch UG, et al. Contrasting activity of cytosin–guanosin dinucleotide oligonucleotides in mice with experimental colitis. Clin Exp Immunol. 2003;134:217–24. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2003.02288.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rachmilewitz D, Karmeli F, Takabayashi K, et al. Immunostimulatory DNA ameliorates experimental and spontaneous murine colitis. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:1428–41. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.32994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rachmilewitz D, Katakura K, Karmeli K, et al. Toll-like receptor 9 signaling mediates the anti-inflammatory effects of probiotics in murine experimental colitis. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:520–8. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sartor RB. Innate immunity in the pathogenesis and therapy of IBD. J Gastroenterol. 2003;38(Suppl. 15):43–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cario E, Rosenberg IM, Brandwein SL, Beck PL, Reinecker HC, Podolsky DK. Lipopolysaccharide activates distinct signaling pathways in intestinal epithelial cell lines expressing Toll-like receptors. J Immunol. 2000;164:966–72. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.2.966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gibson PR. Ulcerative colitis: an epithelial disease? Bailliéres Clin Gastroenterol. 1997;11:17–33. doi: 10.1016/s0950-3528(97)90051-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Otte JM, Cario E, Podolsky DK. Mechanisms of cross hyporesponsiveness to Toll-like receptor bacterial ligands in intestinal epithelial cells. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1054–70. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Berrebi D, Maudinas R, Hugot JP, et al. Card15 gene overexpression in mononuclear and epithelial cells of the inflamed Crohn's disease colon. Gut. 2003;52:840–6. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.6.840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rosenstiel P, Fantini M, Brautigam K, et al. TNF-alpha and IFN-gamma regulate the expression of the NOD2 (CARD15) gene in human intestinal epithelial cells. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:1001–9. doi: 10.1053/gast.2003.50157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pedersen G, Saermark T, Giese B, Hansen A, Drag B, Brynskov J. A simple method to establish short-term cultures of normal human colonic epithelial cells from endoscopic biopsy specimens. Comparison of isolation methods, assessment of viability and metabolic activity. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2000;35:772–80. doi: 10.1080/003655200750023471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pedersen G, Saermark T, Bendtzen K, Brynskov J. Cultures of human colonic epithelial cells isolated from endoscopical biopsies from patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Effect of IFNgamma, TNFalpha and IL-1beta on viability, butyrate oxidation and IL-8 secretion. Autoimmunity. 2000;32:255–63. doi: 10.3109/08916930008994099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brynskov J, Foegh P, Pedersen G, et al. Tumour necrosis factor alpha converting enzyme (TACE) activity in the colonic mucosa of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 2002;51:37–43. doi: 10.1136/gut.51.1.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nielsen OH, Bouchelouche PN, Berild D, Ahnfelt-Ronne I. Effect of 5-aminosalicylic acid and analogous substances on superoxide generation and intracellular free calcium in human neutrophilic granulocytes. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1993;28:527–32. doi: 10.3109/00365529309098261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Takeshita F, Leifer CA, Gursel I, et al. Cutting edge: role of Toll-like receptor 9 in CpG DNA-induced activation of human cells. J Immunol. 2001;167:3555–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.7.3555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hartmann G, Weiner GJ, Krieg AM. CpGDNA: a potent signal for growth, activation, and maturation of human dendritic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:9305–10. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.16.9305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Eckmann L, Kagnoff MF, Falco MT. Colonic epithelial cell lines as a source of interleukin-8: stimulation by inflammatory cytokines and bacterial lipopolysaccharide. Immunology. 1994;82:505. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Naik S, Kelly EJ, Meijer L, Pettersson S, Sanderson IR. Absence of Toll-like receptor 4 explains endotoxin hyporesponsiveness in human intestinal epithelium. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2001;32:449–53. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200104000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hausmann M, Kiessling S, Mestermann S, et al. Toll-like receptors 2 and 4 are up-regulated during intestinal inflammation. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:1987–2000. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.33662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Abreu MT, Arnold ET, Thomas LS, et al. TLR4 and MD-2 expression is regulated by immune-mediated signals in human intestinal epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:20431–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110333200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schmausser B, Andrulis M, Endrich S, et al. Expression and subcellular distribution of toll-like receptors TLR4, TLR5 and TLR9 on the gastric epithelium in Helicobacter pylori infection. Clin Exp Immunol. 2004;136:521–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2004.02464.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kagnoff MF, Eckmann L. Epithelial cells as sensors for microbial infection. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:6–10. doi: 10.1172/JCI119522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Akhtar M, Watson JL, Nazli A, McKay DM. Bacterial DNA evokes epithelial IL-8 production by a MAPK-dependent, NF-kappaB-independent pathway. FASEB J. 2003;17:1319–21. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0950fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jobin C, Sartor RB. The IκB/NF-κB system: a key determinant of mucosalinflammation and protection. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2000;278:C451–62. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2000.278.3.C451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lien E, Ingalls RR. Toll-like receptors. Crit Care Med. 2002;30:S1–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Melmed G, Thomas LS, Lee N, et al. Human intestinal epithelial cells are broadly unresponsive to Toll-like receptor 2-dependent bacterial ligands: implications for host–microbial interactions in the gut. J Immunol. 2003;170:1406–15. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.3.1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cario E, Gerken G, Podolsky DK. Toll-like receptor 2 enhances ZO-1-associated intestinal epithelial barrier integrity via protein kinase C. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:224–38. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zou W, Amcheslavsky A, Bar-Shavit Z. CpG oligodeoxynucleotides modulate the osteoclastogenic activity of osteoblasts via Toll-like receptor 9. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:16732–40. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212473200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gibson PR, Moeller I, Kagelari O, Folino M, Young GP. Contrasting effects of butyrate on the expression of phenotypic markers of differentiation in neoplastic and non-neoplastic colonic epithelial cells in vitro. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1992;7:165–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.1992.tb00956.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mariadason JM, Velcich A, Wilson AJ, Augenlicht LH, Gibson PR. Resistance to butyrate-induced cell differentiation and apoptosis during spontaneous Caco-2 cell differentiation. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:889–99. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.22472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gibson PR, Rosella O, Wilson AJ, et al. Colonic epithelial cell activation and the paradoxical effects of butyrate. Carcinogenesis. 1999;20:539–44. doi: 10.1093/carcin/20.4.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vollmer J, Weeratna RD, Jurk M, et al. Impact of modifications of heterocyclic bases in CpG dinucleotides on their immune-modulatory activity. J Leukoc Biol. 2004;76:585–93. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0104034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ballas ZK, Krieg AM, Warren T, et al. Divergent therapeutic and immunologic effects of oligodeoxynucleotides with distinct CpG motifs. J Immunol. 2001;167:4878–86. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.9.4878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang G, Ghosh S. Negative regulation of toll-like receptor-mediated signaling by Tollip. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:7059–65. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109537200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]