Abstract

The importance of dendritic cells (DC) in the activation of T cells and in the maintenance of self-tolerance is well known. We investigated whether alterations in phenotype and function of DC may contribute to the pathogenesis of Type 1 diabetes (T1DM). Mature DC (mDC) from 18 children with T1DM and 10 age-matched healthy children were tested. mDC, derived from peripheral blood monocytes cultured for 6 days in presence of interleukin (IL)-4 and granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF) and stimulated with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) for the last 24 h, were phenotyped for the expression of the co-stimulatory molecules B7·1 and B7·2. In six patients and six controls allogenic mixed leucocyte reaction (AMLR) was performed using mDC and cord blood-derived naive T cells at a DC/T naive ratio of 1 : 200. Proliferation was assessed on day 7 by [3H]-thymidine incorporation assay. Mature DC derived from patients showed, compared with controls, a reduced expression of B7·1 [mean of fluorescence intensity (MFI): 36·2 ± 14·3 versus 72·9 ± 34·5; P = 0·004] and B7·2 (MFI: 122·7 ± 67·5 versus 259·6 ± 154·1; P = 0·02). We did not find differences in the HLA-DR expression (P = 0·07). Moreover, proliferative response of allogenic naive T cells cultured with mDC was impaired in the patients (13471 ± 9917·2 versus 40976 ± 24527·2 cpm, P = 0·04). We also measured IL-10 and IL-12 concentration in the supernatant of DC cultures. Interestingly, we observed in the patients a sevenfold higher level of IL-10 (P = 0·07) and a ninefold lower level of IL-12 (P = 0·01). Our data show a defect in the expression of the co-stimulatory molecules and an impairment of DC priming function, events that might contribute to T1DM pathogenesis.

Keywords: B7·1/B7·2, dendritic cells, type 1 diabetes

Introduction

Type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) is an autoimmune disease characterized by the selective and progressive destruction of insulin-producing β cells in the pancreas. The aetiology of this organ-specific disorder is multi-factorial, and involves both genetic and environmental factors.

Much of the present understanding about the immunopathology of T1DM results from studies in animal models such as non-obese diabetic (NOD) mice. Several mechanisms have been suggested to contribute to the autoimmune reaction against pancreatic β cells [1,2].

Dendritic cells (DC), antigen-presenting cells with ability to induce primary immune response but also critical for the induction of immunological tolerance, have been implicated in the pathogenesis of T1DM due to their unique antigen presentation capacities and their peri-insular accumulation in the early stage of insulitis in NOD mice [3].

In the steady state DC are in an immature state and express low levels of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II and co-stimulatory molecules (B7 family members). The maturative state is associated with several changes on DC that include the increased formation of MHC-peptide complexes, up-regulation of B7·1 and B7·2, also known as CD80 and CD86, and other molecules that promote DC survival, DC-T cell clustering (CD40, RANK, CD54, CD58) and synthesis of cytokines and chemokines for T cell proliferation and differentiation [4]. The overall structure of B7·1 and B7·2 is very similar, with an extracellular domain containing two Ig-like domains, a transmembrane domain and a cytoplasmic tail with three potential sites for protein kinase C phosphorylation. Despite their structural homology the kinetics and the signals that control B7·1 and B7·2 expression are different. B7·2 is expressed constitutively on DC and its induction occurs within 6 h of stimulation, achieving maximal levels after 18–24 h. In contrast, B7·1 is only weakly expressed on DC with maximal levels detected between 48 and 72 h. Moreover, whereas B7·2 expression is restricted to haematopoietic cells, B7·1 is up-regulated on a variety of other cell types [5].

Expression of co-stimulatory molecules B7 on DC is regulated by T cells through the CD40/CD40L pathway, and by the influence of different types of cytokines. Interleukin (IL)-10, for example, down-regulates B7·2 but not B7·1 expression on DC [6,7]; in contrast, interferon (IFN)-γ increases the expression of B7·2 and B7·1 on peripheral blood monocytes [8]. Also transforming growth factor (TGF)-β can modulate the expression of the B7 family of co-stimulatory molecules, down-regulating their expression.

Although the aetiology of T1DM is at present largely unknown, the destruction of pancreatic β cells seems to be initiated and maintained by autoreactive T cells. The initiation of T cell responses against foreign antigens requires the expression of B7 molecules on immunizing DC. The sequence of events necessary for the induction of CD4+ T cell activation is antigen capture and presentation by DC with subsequent up-regulation of B7, recognition of peptide MHC complex by T cell receptor (TCR) followed by the interaction of B7 molecules with CD28.

Studies that utilize B7-deficient mice and specific monoclonal antibodies have been performed to dissect the specific role of B7·1 and B7·2 in T cell responses [9] but distinct functions for the co-stimulatory ligands have yet to be defined.

The more immunodeficient phenotype of B7·2 knockout mouse suggests that B7·2 is the predominant co-stimulator of T cell activation [10]. In NOD mice the consequence of B7·2 blocking is not predictable and may have different outcomes depending on the stage of disease: anti-B7·2 monoclonal antibody (mAb) treatment, effected in the mice before 10 weeks of age, has protective effects, but the same treatment during the late phase of disease has no influence on disease progression [11]. Alterations in phenotype and impairment in the immune response dependent on DC have been identified previously in the NOD mouse [12,13] as well as in humans at risk for T1DM. Takahashi et al. [14] reported a reduced expression of the co-stimulatory molecules CD80 and CD86 on the surface of DC in individuals at risk of T1DM. A successive study did not confirm these phenotypic abnormalities of DC [15]. The authors reported several impairments at the level of DC and T cells, such as increased expression of CD86 and reduced expression levels of CD54 (ICAM-1) on the surface of immature DC derived from T1DM patients compared to controls.

In order to investigate further the role of DC in the immunopathogenesis of T1DM, in this study we analysed the extent of phenotypic and functional alterations of DC in a paediatric cohort of patients affected by T1DM.

Materials and methods

Subjects

Eighteen children with type 1 diabetes, 10 females and eight males, aged from 1·10 to 16·7 years (mean 11·8 ± 4) (Table 1) from the Department of Pediatrics of Tor Vergata University of Rome, were age- and sex-matched with 10 controls, six females and four males, aged from 9 months to 12 years (mean 7·5 ± 2·9). T1DM was diagnosed according to the definition of the World Health Organization.

Table 1. Clinical characteristics of the patients.

| Patient | Sex | Age (years) | Familiarity for autoimmunity | Age at onset of T1DM* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F | 16·7 | None | 9·7 |

| 2 | M | 10·4 | None | 8·5 |

| 3 | M | 11·3 | Coeliac disease | 9·7 |

| 4 | M | 13·6 | None | 7·6 |

| 5 | M | 12·5 | T1DM | 6·6 |

| 6 | M | 5·3 | None | 1·10 |

| 7 | M | 8·4 | Coeliac diseaseT1DM Thyroiditis | 5·5 |

| 8 | F | 16 | None | 4 |

| 9 | F | 14·8 | Multiple sclerosis | 11·7 |

| 10 | F | 12·4 | None | 6·6 |

| 11 | F | 14·6 | None | 9·11 |

| 12 | F | 13·7 | None | 6·10 |

| 13 | M | 14·5 | None | 8·4 |

| 14 | F | 14·4 | None | 14·2 |

| 15 | F | 10·9 | None | 10·3 |

| 16 | F | 7·6 | None | 6·9 |

| 17 | M | 14·7 | Thyroiditis | 14·2 |

| 18 | F | 1·10 | None | 1·8 |

T1D M: type 1 diabetes mellitus.

Controls were age-matched healthy individuals without familiarity for autoimmune diseases.

Cord blood was obtained from full-term newborns in the absence of either signs of infection or immunosuppression. The Ethical Committee of the hospital approved the study and informed consent was obtained from every study participant after the nature of the study was explained.

Generation of DC from peripheral blood monocytes

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) from patients, healthy donors and cord blood were isolated by gradient centrifugation over Ficoll-Hypaque (Pharmacia Biotech, Upsala, Sweden). Monocytes were isolated from PBMC by positive selection, using anti-CD14-conjugated magnetic Microbeads (MACS; Miltenyi Biotec, Belgish, Gladbach, Germany), resulting routinely in > 95% purity of the CD14+ population, as assessed by flow cytometry. DC were derived from CD14+ cells cultured for 6 days in RPMI-1640 containing 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), supplemented with granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF) (50 ng/ml, Leucomax, Sandoz AG, N¸rnberg, Germany) and IL-4 (10 ng/ml, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA), at a concentration of 4 × 105 cells/ml. After 6 days DC were stimulated for 24 h with 1 µg/ml lipopolysaccharide (LPS) from Escherichia coli (Sigma Chemicals, St Louis, MO, USA) to induce maturation.

Analysis of DC surface phenotype by flow cytometry

DC were stained for 20 min on ice with monoclonal antibodies conjugated to fluoroscein isothyocyanate (FITC) or phycoerythrin (PE), specific for CD14, CD1a, CD11c, HLA-DR, CD80 (B7·1) and CD86 (B7·2) as well as with isotype controls (all from BD PharMingen, San Diego, CA, USA).

A minimum of 1 × 104 events for each sample were acquired with a flow cytometer (FACSCalibur, Beckton Dickinson, San Jose, CA, USA) using CellQuest software (Beckton Dickinson).

DC phenotype was monitored routinely by flow cytometric analysis: immature myeloid DC were defined by the loss of CD14 expression and the up-regulation of CD1a and CD11c molecules, mature DC by high expression of HLA-DR.

Allogenic mixed leucocyte reaction (AMLR)

Naive T cells were isolated from cord blood PBMC by negative selection, using pan T isolation kit (MACS; Miltenyi Biotec, Belgish, Gladbach, Germany), resulting routinely in > 95% CD3+ CD45RA+, as assessed by flow cytometry. T cells (2 × 105/well) were then cultured in 96-well round-bottomed microplates with increasing numbers (100, 1000, 10 000 DC/well) of mature myeloid DC. Proliferation was assessed on day 7 after overnight pulse with 0·5 µCi/well [3H]TdR (Amersham International, Amersham, UK).

Cytokine production assay

Immature and mature DC culture supernatants were harvested and IL-12p70 and IL-10 concentrations were determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (human IL-12 and IL-10 ELISA, Endogen, Woburn, MA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Statistical analysis

Mean differences were analysed with Student's t-test. Values of P < 0·05 were considered significant.

Results

Altered phenotype of DC from children with T1DM

No significant alterations were revealed by the analysis of the phenotype of immature DC derived from peripheral blood monocytes. Down-regulation of CD14 expression and up-regulation of CD1a molecule were similarly observed in children with T1DM and controls.

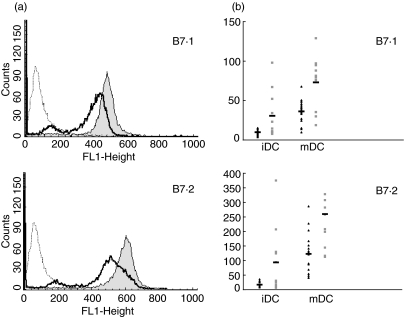

Mature DC generated from patients showed, compared with controls, a similar proportion of cells expressing CD1a, HLA-DR, B7·1 and B7·2. Nevertheless, we observed a significantly lower expression per cell, expressed as mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of the ligands B7·1 (36·2 ± 14·3 versus 72·9 ± 34·5; P = 0·004) and B7·2 (122·7 ± 67·5 versus 259·6 ± 154·1; P = 0·02), after stimulation with LPS. We did not find differences in the HLA-DR expression in both groups of subjects (77·2 ± 48·9 versus 142. 2 ± 91·3; P = 0·07) (Fig. 1a, b). A complete description of the phenotype of either immature and mature DC from T1DM patients and controls is shown in Table 2.

Fig. 1.

Lower expression of B7 markers on dendritic cells (DC) from a type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) patient. (a) An example of flow cytometry analysis of B7·1 (upper panel) and B7·2 (lower panel) cell surface expression on mature DC from a T1DM patient (solid heavy lines) compared with healthy control (filled grey histograms). The dashed lines represents isotype control. The histograms represent mean fluorescence intensities (MFI) of the positive cells for the expression of the markers. (b) B7·1 (upper panel) and B7·2 (lower panel) surface expression on immature DC (iDC) and mature DC (mDC) from T1DM patients (black triangles, n = 18) and healthy controls (grey squares, n = 10).

Table 2. Dendritic cell (DC) phenotype in type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) patients and controls.

| Immature DC | Mature DC | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1DM patients | Controls | T1DM patients | Controls | |

| HLA-DR | 25·6 ± 18·3* | 63·2 ± 60·9 | 77·2 ± 48·9 | 142·2 ± 91·3 |

| (P = n.s.**) | (P = n.s.) | |||

| B7·1 | 9·8 ± 3·5 | 30·6 ± 29·8 | 36·2 ± 14·3 | 72·9 ± 34·5 |

| (P = n.s.) | (P = 0·004) | |||

| B7·2 | 17·2 ± 9 | 93·5 ± 114·3 | 122·7 ± 67·5 | 259·6 ± 154·1 |

| (P = n.s.) | (P = 0·02) | |||

Mean fluorescence intensity ± s.d.

n.s. = not statistically significant.

Impaired AMLR elicited by DC from children with T1DM

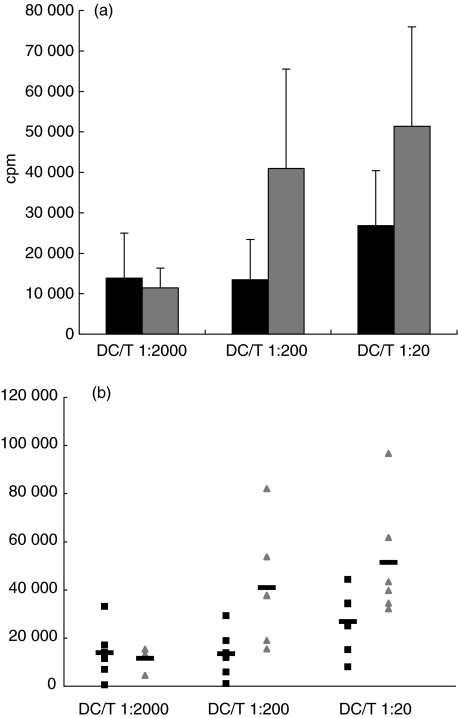

Although DC underwent full maturation, proliferative response of allogenic naive T cells cultured with LPS stimulated DC (DC/T naive ratio of 1 : 200) derived from T1DM children (n = 6) compared with controls (n = 6) was significantly impaired (13471 ± 9917·2 versus 40976 ± 24527·2 cpm, P = 0·04) (Fig. 2a,b).

Fig. 2.

Reduced proliferation of naive T cells after priming with dendritic cells (DC) of type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) patients. Cord blood-derived allogenic T cells were co-cultivated with increasing concentrations of mature monocyte derived DC. Ratio DC/T 1 : 200, P = 0·04. Data from T1DM patients (n = 6) and healthy controls (n = 6), are represented by a histogram (black bars and grey bars, respectively) (a) and a scatter-plot (black squares and grey triangles, respectively) (b).

Cytokine profile of DC from children with T1DM

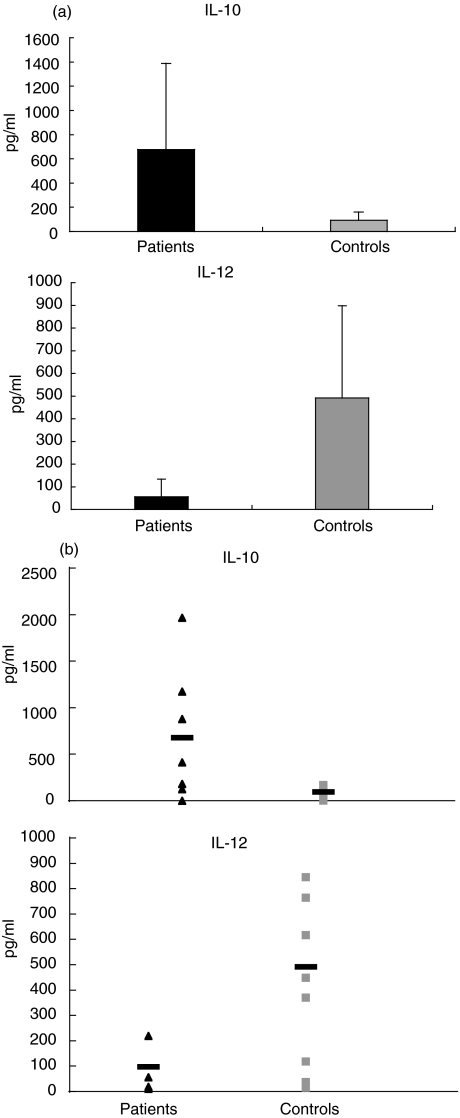

IL-10 and IL-12 were measured in the supernatant of DC cultures in seven patients and in eight age-matched controls. Both cytokines were undetectable in the supernatants of immature DC cultures. Interestingly, after stimulation with LPS, we observed a sevenfold higher production of IL-10 (P = 0·07) and a ninefold lower production of IL-12 (P = 0·01) in the patients compared with controls. (Fig. 3a,b).

Fig. 3.

High levels of interleukin (IL)-10 and low amounts of IL-12 in type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) patients. IL-10 (upper panel) and IL-12 (lower panel) concentrations (P = 0·06 and P = 0·02, respectively) in the supernatants of dendritic cell (DC) cultures of T1DM patients and healthy controls are shown. Data from T1DM patients (n = 7) and healthy controls (n = 8) are represented by a histogram (black bars and grey bars, respectively) (a) and a scatter-plot (black triangles and grey squares, respectively) (b).

Discussion

In this study we demonstrate that DC generated from children affected by T1DM display an altered phenotype and an impaired T stimulatory function. We show that B7·1 and B7·2 expression on mature DC is significantly lower in patients with T1DM than in healthy subjects. The reduced expression of these molecules could be secondary to the increased production of IL-10 by DC of our patients and it is consistent with reports in the literature indicating that IL-10 down-regulates B7 molecules and suppresses immune response [6,16]. It is well known that IL-10 and IL-12 have opposing functions in the immune response and each can counterbalance expression in the other. In our study, as expected, the increase of IL-10 is associated with a reduction of IL-12 production. Although this last observation is apparently in contrast with the Th1 driving activity of IL-12 described in autoimmune diseases, the specific role of IL-12 in the pathogenesis of diabetes is still controversial [7].

Furthermore, we found that DC from T1DM children compared to controls failed to elicitate a proliferative response of allogenic naive T cells. This finding could, in part, be explained by the decreased expression of the co-stimulatory molecules on the DC surface.

CD28/B7 interaction is essential, together with recognition of peptide-MHC molecules by T cell receptors, for lymphocyte activation. B7·1 and B7·2 are also important ligands for CTLA-4, an inhibitory receptor of T cell activation. CTLA-4 ligates to B7·1 and B7·2 with significantly higher affinity than CD28 and delivers a negative signal at later stages in order to down-regulate the immune response [17,18]. Over the past few years a variety of experimental models have shown that the CD28/CTLA-4/B7 co-stimulatory pathway is essential for the control of immune responses. CTLA-4 deficient mice die of a massive lymphoproliferative disease [19] and treatment of BDC2·3 TCR transgenic NOD mice with blocking anti-CTLA-4 mAb results in the acceleration of the autoimmune disease [20]; moreover, an increased severity of type 1 diabetes has been observed in transgenic NOD mice that express soluble circulating CTLA4Ig, a molecule that blocks B7 co-stimulation [11]. The presence of linkage of the CTLA-4 gene with T1DM has been demonstrated by several studies. Linkage analysis have identified a susceptibility locus for type 1 diabetes, which includes CTLA-4 genes, on mouse chromosome 1 (Idd5·1). Moreover, besides T1DM, other autoimmune diseases have been mapped to a syntenic region on human chromosome 2q33 [21,22].

Despite the genetic association between the CTLA-4 gene and T1DM and evidence of the involvement of co-stimulatory molecules in the immunopathogenesis of the disease it seems unlikely that the lower expression of B7 molecules observed in this study is secondary to an altered expression of CTLA-4 molecule on T cells. In a previous study on T cells derived from a paediatric cohort of children affected by T1DM, we analysed the intracellular and the membrane expression of CTLA-4 molecule and did not find evident alteration in the patients compared with age- and sex-matched controls (C. M. Cilio and E. Del Duca, unpublished observation). Our results, in agreement with the work performed on NOD mice by Dahlen [23], suggest the hypothesis that in patients with diabetes an inefficient B7/CD28 co-stimulation secondary to a reduced expression of B7 molecules might result in an impaired up-regulation of CTLA-4, favouring the autoimmune process.

More recently, studies performed on NOD mice suggest the implication of CD28/B7 co-stimulatory pathway in the homeostasis of CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cells: B7·1/B7·2 knockout NOD mice develop severe insulitis and show a severe depletion of the regulatory T cell population [24]. B7-deficient mice, moreover, show reduced T regulatory function due to a deficiency in the T CD25+ CD4+ population, suggesting that expression of B7 co-stimulatory molecules is essential for maintaining self-tolerance [25].

In conclusion, our findings in children with T1DM suggest the hypothesis that a decreased level of B7·1 and B7·2 expression on DC could contribute to the development of type 1 diabetes shifting the immune balance toward an autoreactive T cell phenotype, through a reduced expression of inhibitory receptors or more probably affecting the generation and the homeostasis of regulatory CD4+ CD25+ T cells.

It is now clear that DC have a key role in initial step of the inflammatory process involving pancreatic islets which leads to diabetes, and dysregulation of their tolerogenic functions has been proposed by many authors. For these reasons, and because retroviral mediated transfer techniques are now available to obtain a stable integration of genes in DC, these cells could be a suitable gene therapy vehicle to be delivered to specific sites of inflammation, as has been proposed for other conditions [26,27]. Nevertheless, more work is needed to characterize more effectively DC biological functions in T1DM patients, as successful treatment for autoimmune diseases such as diabetes should specifically target well-known pathogenic mechanisms.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Corrado Maria Cilio and Luigi Racioppi for critical review of the manuscript and Ambrogio Di Paolo for the supply of cord blood samples.

References

- 1.Eisenbarth GS. Type 1 diabetes mellitus. A chronic autoimmune disease. N Engl J Med. 1986;314:1360–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198605223142106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eisenbarth GS. Insulin autoimmunity: immunogenetics/immunopathogenesis of type 1A diabetes. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2003;1005:109–18. doi: 10.1196/annals.1288.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yoon JW, Jun HS, Santamaria PS. Cellular and molecular mechanisms for the initiation and progression of beta cell destruction resulting from the collaboration between macrophages and T cells. Autoimmunity. 1998;27:109–22. doi: 10.3109/08916939809008041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Banchereau J, Briere F, Caux C, et al. Immunobiology of dendritic cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2000;18:767–811. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lenschow DJ, Walunas TL, Bluestone JA. CD28/B7 system of T cell co-stimulation. Ann Rev Immunol. 1996;14:233–58. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.14.1.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buelens C, Willems F, Delvaux A, et al. Interleukin-10 differentially regulates B7-1 (CD80) and B7-2 (CD86) expression on human peripheral blood dendritic cells. Eur J Immunol. 1995;25:2668–72. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830250940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buelens C, Verhasselt V, De Groote D, et al. Human dendritic cell responses to lipopolysaccharide and CD40 ligation are differentially regulated by interleukin-10. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:1848–52. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830270805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hathcock KS, Laszlo G, Pucillo C, et al. Comparative analysis of B7-1 and B7-2 co-stimulatory ligands: expression and function. J Exp Med. 1994;180:631–40. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.2.631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sharpe AH, Freeman GJ. The B7–CD28 superfamily. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:116–26. doi: 10.1038/nri727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sharpe AH. Analysis of lymphocyte co-stimulation in vivo using transgenic and ‘knockout’ mice. Curr Opin Immunol. 1995;7:389–95. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(95)80115-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lenschow DJ, Ho SC, Sattar H, et al. Differential effects of anti-B7-1 and anti-B7-2 monoclonal antibody treatment on the development of diabetes in the nonobese diabetic mouse. J Exp Med. 1995;181:1145–55. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.3.1145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Langmuir PB, Bridgett MM, Bothwell AL, et al. Bone marrow abnormalities in the non-obese diabetic mouse. Int Immunol. 1993;5:169–77. doi: 10.1093/intimm/5.2.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Serreze DV, Gaskins HR, Leiter EH. Defects in the differentiation and function of antigen presenting cells in NOD/Lt mice. J Immunol. 1993;150:2534–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Takahashi M, Honeyman MC, Harrison LC. Impaired yield, phenotype, and function of monocyte-derived dendritic cells in humans at risk for insulin-dependent diabetes. J Immunol. 1998;161:2629–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spatz M, Eibl N, Hink S, et al. Impaired primary immune response in type-1 diabetes. Functional impairment at the level of APCs and T-cells. Cell Immunol. 2003;221:15–26. doi: 10.1016/s0008-8749(03)00043-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Steinbrink K, Wolfl M, Jonuleit H, et al. Induction of tolerance by IL-10-treated dendritic cells. J Immunol. 1997;159:4772–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brunet JF, Denizot F, Luciani MF, et al. A new member of the immunoglobulin superfamily-CTLA-4. Nature. 1987;328:267–70. doi: 10.1038/328267a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Egen JG, Allison JP. Cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen-4 accumulation in the immunological synapse is regulated by TCR signal strength. Immunity. 2002;16:23–35. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00259-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tivol EA, Borriello F, Schweitzer AN, et al. Loss of CTLA-4 leads to massive lymphoproliferation and fatal multiorgan tissue destruction, revealing a critical negative regulatory role of CTLA-4. Immunity. 1995;3:541–7. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90125-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Luhder F, Hoglund P, Allison JP, et al. Cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4) regulates the unfolding of autoimmune diabetes. J Exp Med. 1998;187:427–32. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.3.427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garchon HJ, Bedossa P, Eloy L, Bach JF. Identification and mapping to chromosome 1 of a susceptibility locus for periinsulitis in non-obese diabetic mice. Nature. 1991;353:260–2. doi: 10.1038/353260a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wicker LS, Chamberlain G, Hunter K, et al. Fine mapping, gene content, comparative sequencing, and expression analyses support Ctla4 and Nramp1 as candidates for Idd5.1 and Idd5.2 in the nonobese diabetic mouse. J Immunol. 2004;173:164–73. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.1.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dahlen E, Hedlund G, Dawe K. Low CD86 expression in the nonobese diabetic mouse results in the impairment of both T cell activation and CTLA-4 up-regulation. J Immunol. 2000;164:2444–56. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.5.2444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Salomon B, Lenschow DJ, Rhee L, et al. B7/CD28 co-stimulation is essential for the homeostasis of the CD4+CD25+ immunoregulatory T cells that control autoimmune diabetes. Immunity. 2000;12:431–40. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80195-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lohr J, Knoechel B, Jiang S, et al. The inhibitory function of B7 co-stimulators in T cell responses to foreign and self-antigens. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:664–9. doi: 10.1038/ni939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tarner IH, Slavin AJ, McBride J, et al. Treatment of autoimmune disease by adoptive cellular gene therapy. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2003;998:512–9. doi: 10.1196/annals.1254.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morita Y, Yang J, Gupta R, et al. Dendritic cells genetically engineered to express IL-4 inhibit murine collagen-induced arthritis. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:1275–84. doi: 10.1172/JCI11490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]