Abstract

Monocytes are composed of two distinct subpopulations in the peripheral blood as determined by their surface antigen expressions, profiles of cytokine production and functional roles played in vivo. We attempted to delineate the unique functional roles played by a minor CD16highCCR2− subpopulation of circulating monocytes. They produced significant levels of interleukin (IL)-6 and tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α, but very low levels of IL-10 upon in vitro stimulation. Characteristic profiles of cytokine production were confirmed by stimulating purified subpopulations of monocytes after cell sorting. It was noteworthy that freshly isolated CD16highCCR2− monocyte subpopulations produced significant levels of haem oxygenase (HO)-1, whereas the major CD16lowCCR2+ subpopulation produced little. These results were contrary to the generally accepted notion that the CD16highCCR2− monocyte subpopulation plays a predominantly proinflammatory role in vivo. The CD16highCCR2− subpopulation increased in Kawasaki disease and influenza virus infection. In accord with this, HO-1 mRNA expression by mononuclear cells was significantly increased in these illnesses. These results indicate that CD16highCCR2− subpopulations are of a distinct lineage from CD16lowCCR2+ monocytes. More importantly, they may represent a monocyte subpopulation with a unique functional role to regulate inflammation by producing HO-1 in steady state in vivo.

Keywords: haem oxygenase-1, monocyte, inflammation, cytokine

Introduction

Monocytes play pivotal roles in various stages of self-defence, including phagocytosis of opsonized pathogens, digestion and processing of foreign antigens, antigen presentation in association with class I or class II molecules and finally, release of several inflammatory effector molecules. All these functions constitute critical components of the immune responses. They also determine the direction and the intensity of inflammatory reactions elicited in response to given pathogens through production of selected cytokines with immunomodulating activity [1]. However, excessive production of monocyte-derived cytokines is associated with several chronic inflammatory illnesses [2,3]. Interleukin (IL)-6 and tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α are the representatives of such molecules and recent reports indicate that direct inhibition of their functions can be an effective therapeutic option in some cases of severe inflammatory illnesses [4,5]. It is expected, therefore, that there exist in normal individuals certain mechanisms to counteract the monocyte inflammatory functions and regulate the production of proinflammatory cytokines, protecting cells and tissues from various oxidative stresses.

An inducible form of haem oxygenase (HO), HO-1, is one of the likely candidate molecules for such purposes [6,7]. HO-1 is rapidly induced in vitro upon stimulation and in vivo under various oxidative stresses. Its primary function is to degrade haem into carbon monoxide, biliverdin and free iron. In addition to its role as a key enzyme in haem degradation, it has been reported recently that HO-1 functions as a potent anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidative agent through its production of bilirubin and carbon monoxide (CO) [8–10]. CO not only acts on vascular smooth muscles to dilate the blood vessels, but it also acts on cellular metabolism and counteracts proinflammatory cytokine cascades.

Previous studies have indicated that circulating monocytes are composed of at least two distinct subpopulations based on surface expressions of CD14 and CD16 [11,12]. These two monocyte subpopulations are regarded to be of different lineages because they exhibit separate functions and are characterized by distinct spectrums of cytokine production and chemokine receptor expressions [13–15]. The major classical subpopulation expresses a high level of CD14 and low level of CD16 (CD14highCD16low), whereas the minor ‘proinflammatory’ subpopulation expresses a low level of CD14 and high level of CD16 (CD14lowCD16high) on the cell surface [13]. The classical subpopulation is known to produce anti-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-10, whereas the proinflammatory subpopulation is increased during acute inflammatory illnesses, such as acute phases of Kawasaki disease, sepsis and erysipelas [16–18]. The latter is also increased in chronic inflammatory illnesses such as rheumatoid arthritis and HIV infections, suggesting that they contribute to the enhanced inflammatory reactions [19,20]. They produce significant levels of inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α but produce little IL-10, further supporting the view that they are proinflammatory, but not anti-inflammatory.

In this study, we tried to elucidate the functional differences of these two monocyte subpopulations by comparing the production of inflammatory cytokines and anti-inflammatory protein HO-1. Furthermore, we analysed the distributions of different monocyte subpopulations during acute phases of Kawasaki disease and influenza virus infection.

Subjects and methods

Subjects

Age-matched normal controls (n = 6), patients with acute episodes of influenza virus infection (n = 7) and patients with Kawasaki disease (n = 6) were selected for the analysis. Patients with both influenza virus infection and Kawasaki disease were less than 3 years of age. Influenza virus infection was suspected by clinical symptoms, including high fever, rhinorrhoea, productive cough and impaired general condition. They were associated with low to normal white blood cell (WBC) counts (less than 8000/µl) and low levels of C-reactive proteins (CRP) (less than 1 mg/dl). Diagnosis was confirmed by detecting the viral antigen within nasopharyngeal secretion using a commercial detection kit for influenza virus type A and type B. Kawasaki disease was confirmed when the patient fulfilled the criteria for acute disease, as described previously [21]. In patients with Kawasaki disease, WBC counts ranged from 12 000 to 24 000/µl and CRP concentrations were from 2·4 to 21·6 mg/dl. Ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA) blood samples were collected within 2 days of onset for acute influenza virus infection and within 7 days for Kawasaki disease patients. We used the patients’ samples after obtaining informed consent from their guardians. The study protocol was approved by the Ethical Committee at the Faculty of Medicine, Kanazawa University. In vitro studies of monocyte functions were performed using peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs). PBMCs were separated from 50–100 ml of heparinized peripheral blood obtained from healthy adult volunteers.

Preparation of mononuclear cells and cell cultures

PBMCs were separated from peripheral blood by Ficoll–Hypaque gradient density centrifugation, as described previously [22]. After washing twice with phosphate buffered saline (PBS), the PBMCs were suspended in PBS containing 3% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 0·01% sodium azide (wash buffer) for flow cytometric analysis. For cell cultures, PBMCs were suspended in RPMI-1640 culture medium containing 10% FBS, 25 mmol/l HEPES, 5 × 10−5 mol/l 2-mercaptoethanol, 100 U/ml penicillin and 10 µg/ml gentamycin. All cell cultures were performed at 37°C with 5% CO2. PBMCs or separated monocyte subpopulations (106/ml) were cultured in 4 ml polypropylene tubes (Asahi Techno Glass Co., Tokyo, Japan) without or with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) at 10 ng/ml. For mRNA analysis and supernatant cytokine determinations, cultures were performed for 4 h and 12 h, respectively. After the cultures, supernatants were stored at −20°C for measurement of cytokines, and the cells were used for extraction of total RNA. For intracellular cytokine analysis, cultures were performed for various periods up to 10 h and GolgiStopTM (PharMingen, San Diego, CA, USA) was added for the last 4 h of culture.

Cell surface staining

For cell surface staining, following combination of antibodies was used. Phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated anti-CD14 (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark), fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated anti-CD16 (Coulter Immunotech, Marseille, France) and biotin-conjugated anti-CCR2 antibodies (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) were added simultaneously to PBMC suspension and the mixture was incubated on ice for 20 min. After washing twice in wash buffer, the cells were next reacted with Cy5-conjugated streptavidin (Coulter Immunotech) on ice for 20 min. Expression of Toll-like receptor (TLR)2 and TLR4 was examined after staining PBMC with FITC-conjugated anti-CD16 (Coulter Immunotech) in combination with PE-conjugated anti-TLR2 or anti-TLR4 (both from eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA).

Data were analysed by a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD) using CellQuest software (BD). Monocyte region was gated and cells within the gate were analysed exclusively.

Intracellular staining of cytokines and HO-1

Cultured cells were examined at 0, 4, 6, 8 and 10 h after stimulation for intracellular cytokine production. After surface staining of the cells with FITC-conjugated anti-CD14 (BD), the cells were washed twice in wash buffer. Cells were suspended and fixed with 250 µl Cytofix/Cytoperm™ (PharMingen) for 20 min on ice. After washing twice with 1 ml Perm/Wash™ solution (PharMingen), cells were suspended in 50 µl Perm/Wash™ solution and PE-conjugated anti-cytokine antibodies (anti-IL-6, anti-IL-10 or anti-TNF-α) (all from BD) was added.

HO-1 was detected using mouse anti-HO-1 monoclonal antibody (kind gift of Professor M. Suematsu, Keio University) as the primary antibody and FITC-conjugated anti-mouse IgG antibody (Biosource, Camarillo, CA, USA) as the second antibody. Samples were incubated for 30 min on ice. Thereafter samples were washed twice with 1 ml Perm/Wash™ solution and resuspended in PBS. After staining intracellular HO-1, normal mouse serum was added at 1% to block the unbound sites, followed by surface staining with PE-conjugated anti-CD14.

Data were analysed by a FACSCalibur flow cytometer as described above.

Cell sorting

Monocyte-enriched fractions were prepared after depleting T cells by rosetting PBMCs with 2-aminoethylisouronium bromide (Sigma)-treated sheep erythrocytes. The cells from the non-rosetting fraction were stained for 30 min on ice with FITC-conjugated anti-CD16 antibody and PE-conjugated anti-CCR2 antibody. CD16highCCR2− and CD16lowCCR2+ monocyte subpopulations were separated electronically by using an Epics Elite flow cytometer (Coulter Electronics, Hialeah, FL, USA). Purities were more than 90% for both subpopulations as determined by re-analysis of the sorted cell fractions. More than 99% of the cells from each monocyte subpopulation were detectable within the monocyte gating as defined by forward light-scatter and side-scatter.

Total RNA extraction and reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)

Total cellular RNA was isolated from the monocyte subpopulations with Trizol reagent (Gibco BRL, Bethesda, MD, USA) following the manufacturer's instructions. The RNA was then reverse-transcribed into cDNA in a reaction containing RandamHex Primer (TaKaRa, Otsu, Japan) and RT-Ace (Toyobo, Osaka, Japan). The concentration of RNA was measured by the GeneQuant proRNA/DNA Calculator (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Cambridge, UK).

PCR amplification was performed with TaKaRa Ex Taq™ (TaKaRa); 25–40 cycles for IL-6, IL-10, TNF-α, CCR2B, HO-1 and β-actin were performed with GeneAmp System 9700 (Applied Biosystems, Foster, CA, USA) with sets of 30 s at 94°C and 30 s at 55°C and 45 s at 72°C. The forward and reverse primers, respectively, for these PCR reactions are the following: GCCTTCGGTCCAGTTGCCTT and GCAGAAT GAGATGAGTTGTC for IL-6, ATGCCCCAAGCTGAGAAC CAAGACCCA and TCTCAAGGGGCTGGGTCAGCTATC CCA for IL-10, TCTCGAACCCCGAGTGACAA and TCCC AGATAGATGGGCTCAT for TNF-α, ATGCTGTCCACA TCTCGTTCTCG and TTATAAACCAGCCGAGACTTCC TGC for CCR2B, CGGCTTCAAGCTGGTGATG and GGC TGGTGTGTAGGGGATG for HO-1 and TGGACTTCGAG CAAGAGATG and GATCTTCATTGTGCTGGGTG for β-actin. The PCR products were separated on a 2% agarose gel containing ethidium bromide. Photographs were taken with UV exposure.

Real-time PCR

The upstream and downstream sequences of PCR primers for the HO-1 real-time PCR are 5′-TGAGGAACTTTCA GAAGGGCC-3′ and 5′-TGTTGCGCTCAATCCCTCC-3′, respectively (Funakoshi, Co. Ltd, Tokyo, Japan). A fluorogenic probe (5′-CGGCTTCAAGCTGGTGATGGCC-3′) with a sequence located between the PCR primers was synthesized by PE Applied Biosystems, Japan. The PCR reaction was performed using the TaqMan PCR kit (PE Applied Biosystems) according to the manufacturer's instructions and as described previously [23]. Real-time fluorescence measurement was taken by a model 7700 sequence detector (PE Applied Biosystems), and a threshold cycle (Ct) value for each sample was calculated by determining the point at which the fluorescence exceeded a threshold limit (10× the standard deviation of baseline). For a positive control, a plasmid that contains the HO-1 gene was constructed from the pGEM-T vector (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). A standard graph of the Ct values obtained from serially diluted pGEM-HO-1 was constructed. cDNA samples from the HO-1 negative lymphoma cell line, Daudi served as negative control. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) mRNA was quantified simultaneously, and the HO-1/GAPDH ratio was calculated for each sample.

Statistical analysis

Statistical significance was determined by Student's t-test for Figs 2, 3 and 4b. A Mann–Whitney U-test was used for Figs 5b and 6b. Linear regression analysis was performed to assess the relationship between percentages of monocyte subpopulation and HO-1/GAPDH in Fig. 6c.

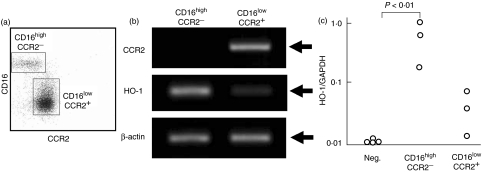

Fig. 2.

Production of haem oxygenase (HO)-1 by isolated monocyte subpopulations. (a) CD16highCCR2− and CD16lowCCR2+ monocyte subpopulations were isolated by electronic cell sorting. (b) Representative data of steady state mRNA levels for CCR2, HO-1 and β-actin are shown. Arrows indicate expected sizes of the transcripts for CCR2 (1083 bp), HO-1 (196 bp) and β-actin (320 bp). (c) For quantitative analysis, expression of HO-1 mRNA was determined by real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and the relative ratio to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) expression was shown as HO-1/GAPDH. cDNA derived from HO-1-defective Daudi served as negative control. Data from three independent experiments are shown.

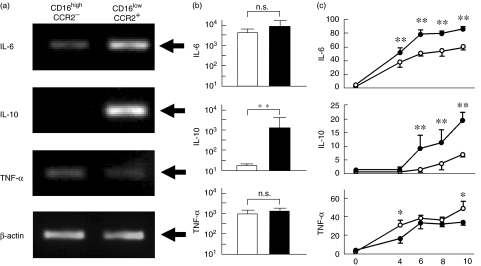

Fig. 3.

Cytokine production by monocyte subpopulations. (a) Isolated monocyte subpopulations were cultured in the presence of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (10 ng/ml) for 4 h and mRNA levels of interleukin (IL)-6, IL-10, tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α and β-actin were compared. Representative data are shown. Arrows indicate expected sizes of the transcripts for IL-6 (565 bp), IL-10 (352 bp) and TNF-α (351 bp) and β-actin (320 bp). (b) After stimulating the isolated monocyte subpopulations with LPS for 12 h, supernatant cytokine concentrations (pg/ml) were determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Mean ± s.d. of three independent experiments are shown. Open and closed columns denote CD16highCCR2− and CD16lowCCR2+ monocyte subpopulations, respectively; **P < 0·01. (c) Mononuclear cells were cultured for indicated period in the presence of LPS and percentages of cytokine-producing cells were determined by a flow cytometry. Numbers in ordinate and abscissa indicate percentages of positive cells and hours of culture, respectively. Open and closed circles indicate CD14low and CD14high monocytes, respectively; **P < 0·01; *P < 0·05.

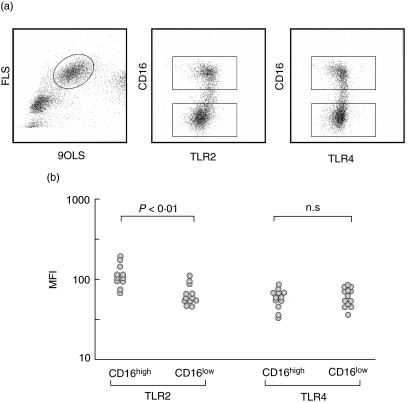

Fig. 4.

Toll-like receptor (TLR) expression on monocyte subpopulations. (a) Representative data of TLR2 and TLR4 expression on monocytes. Levels of TLR2 and TLR4 expressions were compared after gating CD16high and CD16low monocyte subpopulations. (b) TLR2 and TLR4 levels were expressed as mean fluorescence intensities (MFI). CD16high monocytes expressed significantly higher levels of TLR2 than CD16low monocytes (P < 0·01). In contrast, TLR levels were not different between the two subpopulations.

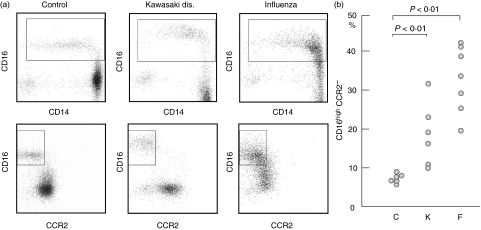

Fig. 5.

Monocyte subpopulations among healthy donors and patients with inflammatory illnesses. (a) Expression of CD16, CD14 and CCR2 was compared among normal controls, Kawasaki disease and influenza virus infection. (b) Percentages of the CD16highCCR2− subpopulation within total monocytes were compared among normal controls (C), patients with Kawasaki disease (K) and patients with influenza virus infection (F).

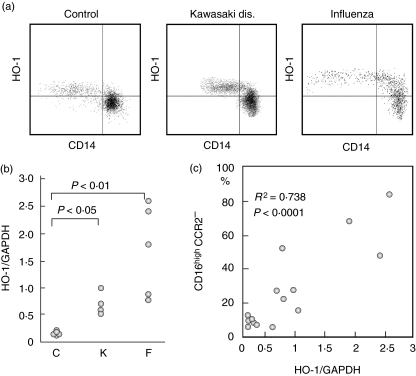

Fig. 6.

Haem oxygenase (HO)-1 production by peripheral blood monocyte subpopulations in patients with inflammatory illnesses. (a) HO-1 expression was compared among different groups of patients by flow cytometry. Representative data are shown. In all three cases, CD14low monocyte subpopulations expressed significantly higher levels of HO-1 than CD14high cells. (b) PBMCs were isolated from normal controls (C), patients with Kawasaki disease (K) or with influenza virus infection (F), and levels of HO-1 mRNA were compared among these groups. (c) Percentages of the CD16highCCR2− subpopulation were compared with the levels of HO-1 mRNA.

Results

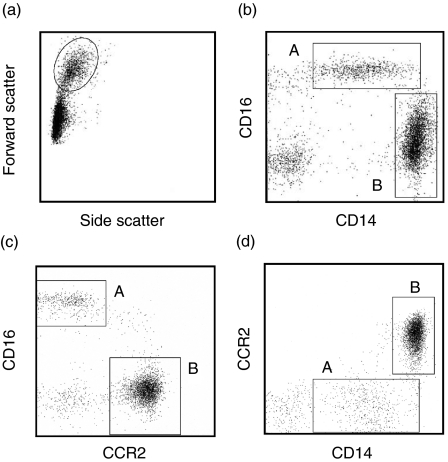

Two different subpopulations of monocytes

Monocytes were divided into two subpopulations by cell-surface expressions of CD14 and CD16 (Fig. 1). Monocyte region was defined by forward light-scatter and side-scatter (Fig. 1a). As described previously, CD14lowCD16high monocytes (A) constituted the minor population and CD14highCD16low monocytes (B) were the major population in healthy donors (Fig. 1b). CD14highCD16low monocytes expressed significant levels of CCR2 chemokine receptors. On the contrary, CD14lowCD16high monocytes expressed hardly detectable levels of CCR2 (Fig. 1c, d). These data show that circulating monocytes are composed of major CD14highCD16lowCCR2+ and minor CD14lowCD16highCCR2− subpopulations.

Fig. 1.

Expression of CD16, CD14 and CCR2 on different monocyte subpopulations. (a) Monocyte region was gated and surface antigen expression was analysed. (b) CD14lowCD16high (A) and CD14highCD16low (B) subpopulations were clearly distinguished. (c, d) CD14lowCD16high cells expressed little CCR2, whereas CD14highCD16low cells expressed high levels of CCR2.

Production of HO-1 by isolated monocyte subpopulations

In the next experiments, we used freshly isolated monocyte subpopulations to compare HO-1 mRNA expressions in vivo. CD16highCCR2− and CD16lowCCR2+ subpopulations were isolated by a cell sorter (Fig. 2a). The purity of the separated subpopulation was more than 90% for each subpopulation, and this was confirmed further by the results of CCR2 mRNA expression, as only CD16lowCCR2+ cells expressed detectable CCR2 mRNA, whereas CD16highCCR2− cells expressed no CCR2 mRNA. Importantly, significant levels of HO-1 mRNA were expressed by the freshly isolated CD16highCCR2− subpopulation. In contrast, it was barely detectable in the CD16lowCCR2+ subpopulation (Fig. 2b). The levels of β-actin were comparable between these two subpopulations. We repeated similar experiments to further confirm the results. The expression of HO-1 mRNA was measured quantitatively by real-time PCR in three separate experiments (Fig. 2c). GAPDH levels were determined simultaneously and used as standard and the data were expressed as HO-1/GAPDH. HO-1/GAPDH for the HO-1-deficient cell line, Daudi, was always below detectable levels, or less than 0·01. As expected, the CD16highCCR2− subpopulation expressed five- to 40-fold higher levels of HO-1 mRNA than the CD16lowCCR2+ subpopulation.

Production of cytokines by two distinct monocyte subpopulations

We next compared the profiles of cytokine mRNA expression by the isolated monocyte subpopulations after in vitro stimulation. The cells were cultured in the presence of LPS and cytokine mRNA was examined by RT-PCR (Fig. 3a). IL-6 mRNA was expressed at higher levels in the CD16lowCCR2+ subpopulation than in the CD16highCCR2− subpopulation. TNF-α mRNA expression was slightly higher in the CD16highCCR2− subpopulation than in the CD16lowCCR2+ subpopulation. Most importantly, IL-10 mRNA was expressed predominantly in the CD16lowCCR2+ subpopulation but it was hardly detectable in the CD16highCCR2− subpopulation. The levels of β-actin were comparable between these two subpopulations. Supernatant samples were collected from the cultures and cytokine concentrations were determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) (Fig. 3b). IL-6, IL-10 or TNF-α production was very low without stimulation (data not shown). After LPS-stimulated cultures, the CD16lowCCR2+ subpopulation (closed columns) produced significantly higher levels of IL-10 than CD16highCCR2− subpopulation (open columns). IL-6 and TNF-α concentrations were comparable between the two monocyte subpopulations. We next compared intracellular cytokine expressions by CD14high and CD14low monocytes after stimulating PBMC with LPS (Fig. 3c). IL-6 and TNF-α were produced by both subpopulations of monocytes, although the IL-6 levels were significantly higher in CD14high cells throughout the culture. TNF-α concentrations were comparable between the two subpopulations. In contrast, IL-10 production was significantly lower in CD14low cells than CD14high cells throughout the culture.

TLR expressions by monocyte subpopulations

Expression of TLR2 and TLR4 was compared in normal control subjects (Fig. 4a, b). CD16high monocyte subpopulations expressed significantly higher levels of TLR2 than CD16low cells, whereas TLR4 expression was similar between the two subpopulations.

Monocyte subpopulations in patients with Kawasaki disease or with influenza virus infection

We compared the distributions of the monocyte subpopulations among healthy donors (C), patients with Kawasaki disease (K) or influenza virus infection (F) to know the clinical relevance of the different monocyte subpopulations. In healthy controls, the CD14lowCD16high subpopulation constitutes a minor subpopulation and consisted of 10% among circulating monocytes, but this particular subpopulation increased significantly among patients with Kawasaki disease and influenza virus infection (Fig. 5a). It is of note that the CD14lowCD16high subpopulation remained a distinct subpopulation with enhanced CD16 expression in Kawasaki disease, whereas the CD14highCD16low subpopulation coalesced with the CD14lowCD16high subpopulation with enhanced CD16 and reduced CCR2 expression in influenza virus infection. When the percentages of the CD14lowCD16high subpopulations were compared among these different conditions, the numbers were significantly higher in both Kawasaki disease and influenza virus infection than normal controls (Fig. 5b). Although the numbers tended to be higher in influenza virus infection than in Kawasaki disease, the difference was not statistically significant between both groups.

Expression of HO-1 in patients with Kawasaki disease and influenza virus infection

Flow cytometric analysis revealed that HO-1 protein expression is significantly higher among CD14low subpopulations than CD14high subpopulations both in controls and in patients with Kawasaki disease or influenza virus infection (Fig. 6a). HO-1 mRNA expression by PBMC was significantly higher in the patients with Kawasaki disease (P < 0·05) and with influenza virus infection (P < 0·01) compared with normal controls (Fig. 6b). Patients with influenza virus infection tended to express higher levels of HO-1 mRNA than patients with Kawasaki disease, although the differences were not statistically significant between the two groups. Levels of HO-1 mRNA expression correlated well with the percentages of the CD16highCCR2− subpopulations within monocytes (R2 = 0·738, P < 0·001) (Fig. 6c).

Discussion

Recently, there is increasing evidence indicating that HO-1 and its major metabolites, CO and bilirubin act as potent anti-inflammatory mediators [24]. In supporting this notion, the abolition of HO-1 activity by gene targeting rendered the mice extremely susceptible to oxidative stress [25]. In humans we reported that persistent, systemic inflammation was the principal feature of the HO-1 deficiency patient [26]. In addition, transfer of the HO-1 gene reduced the level of inflammation and the risk of rejection of transplanted organs, suggesting that the presence of excessive HO-1 reduces the level of inflammatory immune reactions [27]. CO acts on monocytes to regulate the production of proinflammatory cytokines and enhancing IL-10 production [15]. Furthermore, IL-10 is now known to exert its anti-inflammatory effects through induction of HO-1 [28]. These findings indicate clearly that HO-1, CO and IL-10 function as anti-inflammatory mediators in vivo.

We have shown previously that among peripheral blood leucocytes, monocytes are the principal source of HO-1 when they are stimulated in vitro [23]. Monocyte HO-1 production was increased in various inflammatory illnesses of childhood, including Kawasaki disease and various infections of bacterial and viral origins. It was noted that only a small fraction of monocytes produced particularly significant levels of HO-1 during acute inflammatory illnesses. Circulating monocytes from the patient with HO-1 deficiency showed characteristic morphology with basophilic, vacuolar cytoplasm, associated with prominent reduction of surface HLA-DR and CD36 expression [26,29]. It was suggested that uncontrolled oxidative stress resulted in the characteristic morphological alteration of monocytes. We have shown in in vitro experiments that these phenotypic changes were associated closely with the defect of monocyte phagocytic function. These results suggested that monocyte HO-1 production play central roles in systemic inflammation and the lack of HO-1 directly influences the anti-inflammatory functions of monocytes.

Monocytes are known to be composed of two, presumably distinct subpopulations, characterized by different patterns of surface antigen expression, cytokine production and migrating capacities [11–15]. However, to date the separate roles played by these two different monocyte subpopulations have been revealed only partially. It has been suggested that the CD16 highCCR2− minor subpopulations represent ‘proinflammatory’ monocytes based on the finding that they produce higher levels of inflammatory cytokines upon stimulation [13]. Expression of higher levels of the fractalkine receptor, CX3CR1, is also regarded as an indicator of the proinflammatory role of this subpopulation [14]. We propose possibly different roles for this particular monocyte subpopulation for the following reasons.

Monocyte apoptosis should always be considered in dealing with monocyte cultures. In preliminary experiments, we checked monocyte apoptosis induced in in vitro-stimulated cultures by Annexin V binding. It is induced predominantly in CD16+ monocytes when they are stimulated with dexamethasone, but only after 12 h of culture (data not shown). Therefore, we consider that monocyte apoptosis is negligible within the time-scale of our cultures. Experiments using isolated monocyte subpopulations showed that both subpopulations are capable of producing IL-6 and TNF-α at comparable levels. Although there were some differences in IL-6 and TNF-α mRNA expression between the two subpopulations, repeated measurement of culture supernatants showed no significant differences in the production of these cytokines; therefore the differences in production of these cytokines are only relative, but not absolute. Frankenberger et al. also used isolated monocyte subpopulations and TNF-α production was observed similarly in both subpopulations with LPS stimulation [13]. In contrast, Belge et al. obtained contrary data by flow cytometric analysis of intracellular cytokine expression using whole blood cell cultures [30]. Although IL-10 production was limited to the CD142+ CD16− subpopulation, similar to our results, TNF-α production was observed predominantly within the CD14+ CD16+ subpopulation. These contradictory data may result from the differences in methods of cell isolation and culture. Although the use of isolated monocyte subpopulations is preferable to exclude the possible interactions between different cell populations, it may not reflect directly what is operating in vivo. It is certain, however, that the CD16highCCR2− subpopulation of monocytes are capable of producing proinflammatory cytokines at least at a level comparable to CD16lowCCR2+ subpopulations.

Nevertheless, the profiles of the IL-10 production by different monocyte subpopulations were distinct. As described previously [13], the CD16highCCR2− subpopulation produced little, if any, IL-10 upon stimulation. This is not due to the fact that CD16highCCR2− monocytes respond poorly to LPS, because they produce significant levels of IL-6 and TNF-α. In supporting this, expression of LPS receptor TLR4 was comparable between the two subpopulations. Therefore, distinct profiles of cytokine production by CD16highCCR2− and CD16lowCCR2+ subpopulations reflect the fact that they are of two different lineages of monocytes, rather than a continuum of a single cell population.

We do not know why the CD16highCCR2− subpopulation did not produce the important anti-inflammatory cytokine, IL-10, upon stimulation, if these cells exert an anti-inflammatory role. One possible explanation is that the CD16highCCR2− subpopulation produces HO-1 at steady state in vivo, thereby inhibiting IL-10 production by a feedback mechanism. To support this, IL-10 was induced in the CD16highCCR2− subpopulation at low, but significant levels later in in vitro culture. Another possibility is that they produce HO-1 through a distinct mechanism from the major CD16lowCCR2+ subpopulation. We are currently actively investigating the latter possibility.

Geissmann et al. showed recently in an elegant experiment using a murine adoptive transfer system that the CX3CR1high monocyte subpopulations do not represent proinflammatory cells [31]. Rather, they are similar in many respects to resident macrophages. In contrast, the CX3CR1low subpopulation is migrating actively to inflammatory tissues, contributing to tissue injury. It was shown further that the CX3CR1high subpopulation expresses high levels of CD16 and lack CCR2 on the surface, suggesting that the CX3CR1high subpopulation is a murine counterpart of the human CD16highCCR2− monocyte subpopulation.

In this paper, the notion is supported further by the fact that the CD16highCCR2− subpopulation is the major HO-1 producer at the steady state in vivo. This holds true during acute inflammatory illnesses, as the fraction of the CD16highCCR2− subpopulation increases along with the increase of HO-1 production in vivo. Higher TLR2 levels in the CD16highCCR2− subpopulation may explain high levels of HO-1 expression in vivo. Preferential ligand binding to TLR2 may constantly induce HO-1 in this monocyte subpopulation. Lack of HO-1 production by the CD16lowCCR2+ subpopulation can be explained by negative regulation with LPS stimulation. It has been shown that HO-1 production induced by IL-10 is inhibited by LPS in macrophages [32]. To support this further, our preliminary experiments show that CD16lowCCR2+ subpopulations produce significant levels of HO-1 upon stimulation with sodium arsenite, but not with LPS (data not shown). It has to be proved if these negative and positive regulatory mechanisms are operating in vivo.

Increase during acute inflammatory illnesses is one of the reasons that many consider this subpopulation as proinflammatory. However, as shown in this study and also by the murine adoptive transfer experiment [31], CD16highCCR2− subpopulation may also play a paradoxical anti-inflammatory role and the increase of these cells presumably reflect a preferential expansion of the CD16highCCR2− subpopulation for the protection of inflammatory tissues and organs, rather than for the promotion of inflammation. It is intriguing in this respect that profiles of CD14, CD16 and CCR2 expression are different between patients with Kawasaki disease and influenza virus infection. Although the CD16highCCR2− subpopulation expanded in both illnesses, influenza virus infection was associated with the increase of monocytes with intermediate levels of CD16 and CCR2 expression. The clinical significance of these differences is not known, but they may reflect distinct profiles of inflammatory reactions observed between the two acute inflammatory illnesses. Acute influenza virus infection is characterized by normal leucocyte numbers and low CRP levels, reflecting a significant but limited duration of inflammatory cytokine production. In contrast, patients with Kawasaki disease always present with increased leucocyte counts and significantly elevated CRP levels, suggesting prolonged and intense inflammatory reactions. Further study is necessary to delineate distinct, if any, role played by these CD16intermediate CCR2 intermediate monocytes.

There are increasing numbers of reports on the functional significance of CCR2 expression on the monocyte surface [33,34]. The CD16lowCCR2+ monocyte subpopulation is shown to be responsible for vascular neointima formation in a murine model of hypertension-induced vascular inflammation [35]. On the contrary, this particular subpopulation may play a significant role in collateral artery growth after arterial occlusion, by migrating actively into the arterial lesion and eliciting arteriogenesis through CCR2 signalling [36]. These findings, in conjunction with data by Geissmann et al. [31], suggest that the major fraction of circulating monocytes CD16lowCCR2+ is the subpopulation involved actively in cytokine production and vascular remodelling in the event of inflammation and vascular injury.

It is now clear from these data that peripheral blood monocytes are composed of two distinct subpopulations. These monocyte subpopulations differ not only phenotypically, but also functionally, presumably reflecting distinct cell lineages. Although in vitro data suggest that the minor CD16highCCR2− subpopulation represent proinflammatory monocytes, promoting tissue inflammation with enhanced migratory capacity and cytokine production, this particular subpopulation produces significant levels of HO-1 in steady state, suggesting that they may play a cardinal anti-inflammatory role in vivo. Pharmacological modulation of the function of these monocytes in vivo may provide a novel therapeutic intervention. In this regard, it is important that Morita et al. reported recently that pharmacological induction of HO-1 within monocytes suppressed CCR2 expression and angiotensin II-elicited chemotactic activity [37].

Alternatively, CD16highCCR2− and CD16lowCCR2+ subpopulations may form paracrine networks with distinct but interacting functions and together they may accelerate or regulate inflammation, depending on the levels and nature of external stimuli. In supporting this notion, HO-1 is induced by IL-6 [38] and may exert proinflammatory effects by triggering monocyte survival and proliferation [39].

Further study is necessary to elucidate the functional roles played in vivo by different monocyte subpopulations.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant-in-aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan and by a grant from the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare of Japan. We thank Ms Harumi Matsukawa and Ms Emi Tamamura for excellent technical assistance.

References

- 1.Akira S, Hemmi H. Recognition of pathogen-associated molecular patterns by TLR family. Immunol Lett. 2003;85:85–95. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2478(02)00228-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ravell A. Macrophage activation syndrome. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2002;14:548–52. doi: 10.1097/00002281-200209000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cuende E, Vesga JC, Perez LB, Ardanaz MT, Guinea J. Macrophage activation syndrome as the initial manifestation of systemic onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2001;19:764–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barrera P, Joosten LA, den Broeder AA, van de Putte LB, van Riel PL, van den Berg WB. Effect of treatment with a fully human anti-tumor necrosis factor α monoclonal antibody on the local and systemic homeostasis of interleukin 1 and TNFα in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2001;60:660–9. doi: 10.1136/ard.60.7.660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feldmann M, Maini RN. Anti-TNFα therapy of rheumatoid arthritis: What have we learned? Ann Rev Immunol. 2001;19:163–96. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maines MD. Haem oxygenase: function, multiplicity, regulatory mechanism, and clinical applications. FASEB J. 1988;2:2557–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abraham NG, Drummond GS, Lutton JD, Kappas A. The biological significance and physiological role of haem oxygenase. Cell Physiol Biochem. 1996;6:129. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Willis D, Moore AR, Frederick R, Willoughby DA. Haem oxygenase: a novel target for the modulation of the inflammatory response. Nat Med. 1996;2:87–90. doi: 10.1038/nm0196-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Platt JL, Nath KA. Haem oxygenase: protective gene or Trojan horse. Nat Med. 1998;4:1364–5. doi: 10.1038/3947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Otterbein LE, Bach FH, Alam J, et al. Carbon monoxide has anti-inflammatory effects involving the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. Nat Med. 2000;6:422–8. doi: 10.1038/74680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Passlick B, Flieger D, Ziegler-Heitbrock HW. Identification and characterization of a novel monocyte subpopulation in human peripheral blood. Blood. 1989;74:2527–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ziegler-Heitbrock HW, Fingerle G, Strobel M, Ziegler-Heitbrock HW. The novel subset of CD14+/CD16+ blood monocytes exhibits features of tissue macrophages. Eur J Immunol. 1993;23:2053–8. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830230902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frankenberger M, Sternsdorf T, Pechumer H, Pforte A, Ziegler-Heitbrock HW. Differential cytokine expression in human blood monocyte subpopulations: a polymerase chain reaction analysis. Blood. 1996;87:373–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ancuta P, Rao R, Moses A, et al. Fractalkine preferentially mediates arrest and migration of CD16+ monocytes. J Exp Med. 2003;197:1701–7. doi: 10.1084/jem.20022156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grage-Griebenow E, Flad HD, Ernst M. Heterogeneity of human peripheral blood monocyte subsets. J Leukoc Biol. 2001;69:11–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blumenstein M, Boekstegers P, Fraunberger P, Andreesen R, Ziegler-Heitbrock HWL, Fingerle-Rowson G. Cytokine production precedes the expression of CD14+CD16+ monocytes in human sepsis: a case report of a patient with self-induced septicemia. Shock. 1997;8:73–5. doi: 10.1097/00024382-199707000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Katayama K, Matsubara T, Fujiwara M, Koga M, Furukawa S. CD14+CD16+ monocyte subpopulation in Kawasaki disease. Clin Exp Immunol. 2000;121:566–70. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2000.01321.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Horelt A, Belge KU, Steppich B, Prinz J, Ziegler-Heitbrock L. The CD14+CD16+ monocytes in erysipelas are expanded and show reduced cytokine production. Eur J Immunol. 2002;32:1319–27. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200205)32:5<1319::AID-IMMU1319>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kawanaka N, Yamamura M, Aita T, et al. CD14+,CD16+ blood monocytes and joint inflammation in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:2578–86. doi: 10.1002/art.10545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thieblemont N, Weiss L, Sadeghi HM, Estcourt C, Haeffner-Cavaillon N. CD14lowCD16high: a cytokine-producing monocyte subset which expands during human immunodeficiency virus infection. Eur J Immunol. 1995;25:3418–24. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830251232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kawasaki T, Kosaki F, Okawa S, Shigematsu I, Yanagawa H. A new infantile acute febrile mucocutaneous lymph node syndrome (MLNS) prevailing in Japan. Pediatrics. 1974;54:271–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kasahara Y, Miyawaki T, Kato K, et al. Role of interleukin 6 for differential responsiveness of naive and memory CD4+ T cells in CD2-mediated activation. J Exp Med. 1990;172:1419–24. doi: 10.1084/jem.172.5.1419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yachie A, Toma T, Mizuno K, et al. Haem oxygenase-1 production by peripheral blood monocytes during acute inflammatory illnesses of children. Exp Biol Med. 2003;228:550–6. doi: 10.1177/15353702-0322805-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yoshida T, Kikuchi G. Features of the reaction of haem degradation catalyzed by the reconstituted microsomal haem oxygenase system. J Biol Chem. 1978;253:4230–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Poss KD, Tonegawa S. Reduced stress defense in haem oxygenase 1-deficient cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:10925–30. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.20.10925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yachie A, Niida Y, Wada T, et al. Oxidative stress causes enhanced endothelial cell injury in human haem oxygenase-1 deficiency. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:129–35. doi: 10.1172/JCI4165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Soares MP, Lin Y, Anrather J, et al. Expression of haem oxygenase-1 can determine cardiac xenograft survival. Nat Med. 1998;4:1073–7. doi: 10.1038/2063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee T-S, Chau L-Y. Haem oxygenase-1 mediates the anti-inflammatory effect of interleukin-10 in mice. Nat Med. 2002;3:240–6. doi: 10.1038/nm0302-240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yachie A, Kawashima A, Ohta K, Saikawa Y, Koizumi S. Human HO-1 deficiency and cardiovascular dysfunction. In: Wang R, editor. Carbon monoxide and cardiovascular functions. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2002. pp. 181–212. ed. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Belge K-U, Dayyani F, Horelt A, et al. The proinflammatory CD14+ CD16+ DR+ monocytes are a major source of TNF. J Immunol. 2002;168:3536–42. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.7.3536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Geissmann F, Jung S, Littman DR. Blood monocytes consist of two principal subsets with distinct migratory properties. Immunity. 2003;19:71–82. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00174-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Giuseppe A, Ricchetti A, Williams LM, Foxwell BMJ. Haem oxygenase 1 expression induced by IL-10 requires STAT-3 and phosphoinositol-3 kinase and is inhibited by lipopolysaccharide. Leukoc Biol. 2004;76:719–26. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0104046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dambach DM, Watson LM, Gray KR, Durham SK, Laskin DL. Role of CCR2 in macrophage migration into the liver during acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity in the mouse. Hepatology. 2002;35:1093–103. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.33162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fantuzzi L, Borghi P, Ciolli V, Pavlakis G, Belardelli F, Gessani S. Loss of CCR2 expression and functional response to monocyte chemotactic protein (MCP-1) during the differentiation of human monocytes: role of secreted MCP-1 in the regulation of the chemotactic response. Blood. 1999;94:875–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ishibashi M, Hiasa K, Zhao Q, et al. Critical role of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 receptor CCR2 on monocytes in hypertension-induced vascular inflammation and remodeling. Circ Res. 2004;94:1203–10. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000126924.23467.A3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Heil M, Ziegelhoeffer T, Wagner S, et al. Collateral artery growth (arteriogenesis) after experimental arterial occlusion is impaired in mice lacking CC-chemokine receptor-2. Circ Res. 2004;4:671–7. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000122041.73808.B5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Morita T, Imai T, Yamaguchi T, Sugiyama T, Katayama S, Yoshino G. Induction of haem oxygenase-1 in monocytes suppresses angiotensin II-elicited chemotactic activity through inhibition of CCR2: role of bilirubin and carbon monoxide generated by the enzyme. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2003;5:439–47. doi: 10.1089/152308603768295186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tron K, Novosyadlyy R, Dudas J, Samoylenko A, Kietzmann T, Ramadori G. Upregulation of haem oxygenase- gene by turpentine oil-induced localized inflammation: involvement of interleukin-6. Laboratory Invest. 2005;85:376–87. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Devesa I, Ferrandiz ML, Guillen I, Cerda JM, Alcaraz MJ. Potential role of haem oxygenase-1 in the progression of rat adjuvant arthritis. Laboratory Invest. 2005;85:34–44. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]