Abstract

Interleukin (IL)-18 is considered to induce exclusively the Th1 immune response but not the Th2 response in the presence of adequate IL-12 stimulation in bacterial infections. However, we demonstrate herein that multiple IL-18 injections to the mice not only enhance the early Th1 response but also stimulate the Th2 response later after viable Escherichia coli infection. Multiple IL-18 injections (three alternate-day injections) raised the serum interferon (IFN)-γ level at 6 h and serum Th2 cytokine levels, such as IL-4, IL-10 and IL-13, at 48 h after infection, while a single IL-18 injection increased only the serum IFN-γ level. Depletion of mouse CD4+ cells suppressed the IL-18-induced Th2 cytokines, IL-4, IL-10 and IL-13. In contrast, depletion of natural killer (NK)1·1+ cells reduced the IFN-γ and IL-13 levels. Moreover, multiple IL-18 injections up-regulated the serum IgM level at 72 h after infection while a single IL-18 injection did not. Interestingly, neutralization of IL-4 but not IFN-γ partially suppressed the increased serum IgM.

Liver mononuclear cells (MNCs) from the mice treated with multiple IL-18 injections significantly increased more production of not only IFN-γ but also Th2 cytokines and IgM by in vitro lipopolysaccharide (LPS) stimulation than those from the phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)-treated mice, while liver MNCs from the single IL-18-injected mice also increased IFN-γ production but significantly suppressed IL-4 and IgM production compared to those from the PBS-treated mice. Our findings suggest that multiple injections of IL-18 up-regulate both the cellular and humoral innate immunities, thereby enhancing host defence against bacterial infections.

Keywords: bacterial infection, immunoglobulin M, innate immunity, interleukin-18, Th1/Th2 cytokines

Introduction

Interleukin (IL)-18 was discovered originally as a factor that induces interferon (IFN)-γ production from natural killer (NK) cells and CD4+T cells [1,2]. In collaboration with IL-12, IL-18 stimulates Th1-mediated immune responses, which play a crucial role in host defence against bacterial infection through the induction of IFN-γ[3–10]. In our recent study, we also demonstrated that multiple IL-18 injections augment IFN-γ production from liver NK cells in immunocompromized burned mice and greatly reduce their mortality in bacterial peritonitis or sepsis [3,4]. In contrast, multiple IL-18 injections without IL-12 or in the absence of bacterial infection have also been shown recently to stimulate IL-4 production from T cells and IgE production from B cells, thus suggesting that they may play a role in allergic disorders. IL-18 is thus a functionally pleiotropic and complex cytokine that is involved in either the Th1 or Th2 immune response [2,11–16], depending upon the host environment.

On the other hand, IgM is the first class of immunoglobulin that is produced from B cells as a potent complement activator during the early stage of infections [17–19]. Binding IgM with bacteria and activation of the complement system by IgM can either induce the lysis of invading bacteria or enhance the opsonization of infectious particles for efficient phagocytosis by macrophages and neutrophils [20–23]. IgM is thus an important defence mechanism against bacteria which takes effect before the IgG-mediated defence mechanism begins. Both Th1/Th2 cytokines and cellular immunity/humoral immunity are believed to play an important role in host defence against bacterial infections and they should thus be coordinated in an as-yet undefined but sophisticated manner [24,25].

In the present study, in order to examine the biological effects of IL-18 on the Th1/Th2 balance and cellular/humoral immunity in the host, we investigated and compared the effect between a single IL-18 pretreatment and multiple IL-18 pretreatments in mice during the course of a bacterial infection, using mice with a sublethal Escherichia coli infection, which enabled us to observe the mice beyond the initial acute phase of infection. The present results are considered to provide new insight into the functions of a unique pleiotropic cytokine, namely IL-18.

Materials and methods

This study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Institutional Review Board for the Care of Animal Subjects at the National Defense Medical College, Japan.

Mice and reagents

Male C57BL/6 mice (8 weeks old, 20 g) were purchased from Charles River Inc. (Yokohama, Japan). E. coli strain B [American Type Culture collection (ATCC) 11303, Sigma Co., St Louis, MO, USA] were grown in brain heart infusion broth (Difco Co. Ltd, Detroit, MI, USA) and used for the experiments. The intravenous (i.v.) injection dose of E. coli, which produced a 50% lethality (LD50), was 7·5 × 108 colony-forming units (CFU). Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (E. coli 0111: B4, Sigma) was also used for the experiments.

IL-18 treatment (multiple or single IL-18 injections) and E. coli challenge

Mouse recombinant IL-18 was obtained from MBL (Nagoya, Japan). Multiple IL-18 injections were performed by injecting the mice three times with intraperitoneal (i.p.) injections of IL-18 (0·2 µg/0·5 ml/mouse) on alternate days (days −4, −2 and 0 of E. coli challenge). The single IL-18 injection consisted of two i.p. injections of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (0·5 ml/mouse, days −4 and −2) and a subsequent i.p. injection of IL-18 (day 0). Sham treatment was performed by three i.p. injections of PBS (days −4, −2 and 0). The mice were challenged i.v. with 1 × 108 CFU of E. coli at 2 h after the last injection of IL-18 or PBS.

Neutralization of IFN-γ or IL-4

To neutralize IFN-γ or IL-4, anti-mouse IFN-γ antibody (500 µg/mouse, Sigma) or anti-mouse IL-4 antibody (500 µg/mouse, Sigma) was injected i.v. into the mice at 1 h before the E. coli challenge. As an isotype control of anti-IFN-γ antibody or anti-IL-4 antibody, goat IgG1 (500 µg/mouse, Sigma) was used.

In vivo depletion of NK1·1+ cells or CD4+ cells

Anti-NK1·1 antibody and anti-mouse CD4 antibody were derived from PK136 and GK1·5 hybridoma cells (IBL, Gunma, Japan), respectively. Next, the mice were injected i.v. with either anti-NK1·1 antibody (200 µg/mouse) or anti-CD4 antibody (500 µg/mouse) 3 days before the E. coli challenge. These antibodies deplete NK1·1+ (NK and NK T) cells or CD4+ cells for approximately 1 week, as reported previously [26,27].

Isolation of liver, spleen and bone marrow mononuclear cells (MNCs)

Under deep anaesthesia with ether, the mice were euthanized to remove their livers and spleens. Liver and spleen MNCs were obtained as described previously [28–30]. Briefly, the liver was minced and suspended in Hanks's balanced salt solution containing 0·05% collagenase (Wako, Osaka, Japan). After undergoing shaking incubation for 20 min at 37°C, the liver specimen was passed through a 200-gauge stainless steel mesh. The cells were washed, suspended in 33% Percoll solution and centrifuged at 500 g for 20 min at room temperature. The pellet was resuspended in red blood cell (RBC) lysing solution and was then washed twice in 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) RPMI-1640. Similarly, the splenocytes were passed through a stainless steel mesh and were then treated with the RBC lysing solution, and were finally washed twice in 10% FBS RPMI-1640. Bone marrow cells were obtained by injecting 1% FBS RPMI-1640 into the femurs using a 1 ml syringe with a 26-gauge needle and were then treated with the RBC lysing solution, and were finally washed twice in 10% FBS RPMI-1640.

Cell cultures

The MNCs obtained from liver, spleen and bone marrow were stained with Turk solution (Wako, Osaka, Japan) and then counted by a microscope. After counting, 5 × 105 of MNCs in 200 µl of 10% FBS RPMI-1640 medium were cultured in 96-well flat-bottomed plates in 5% CO2 at 37°C for 24 h and then the culture supernatants were stocked at −80°C until the assays were performed.

In vitro LPS stimulation for liver and spleen MNCs obtained from the IL-18-treated mice

Liver and spleen MNCs were obtained from the mice treated by either multiple IL-18 injections, a single IL-18 injection or PBS injections (without E. coli challenge). Subsequently, the cells were cultured in 5% CO2 at 37°C for 48 h or 72 h with 10 µg/ml of LPS and the culture supernatants were then stocked at −80°C until assay.

Measurement of cytokine or immunoglobulin levels using sera and culture supernatants

Blood samples were obtained by a retro-orbital plexus puncture. The sera were stored at −80°C until the assays were performed. IFN-γ, IL-4, IL-10, total IL-12 and IL-13 levels of the sera or the culture supernatants were measured using cytokine-specific enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits (IFN-γ, IL-4, IL-10: Pharmingen, San Diego, CA, USA; IL-12: Endogen, Woburn, MA, USA; IL-13: R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA). IgM level of the sera or of the culture supernatants was measured using an ELISA quantification kit (Bethyl Laboratories Inc., Montgomery, TX, USA).

Statistical analysis

The data are presented as the mean values ± s.e. Statistical analyses were performed using an iMac computer (Apple, Cupertino, CA, USA) and the StatView 4·02 J software package (Abacus Concepts, Berkeley, CA, USA). Statistical evaluations were compared using the standard one-way analysis of variance followed by the Bonferoni post-hoc Test. A P-value of less than 0·05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Multiple IL-18 injections increased both the serum Th1 and Th2 cytokine levels while a single IL-18 injection increased only the serum Th1 cytokine level in E. coli-challenged mice

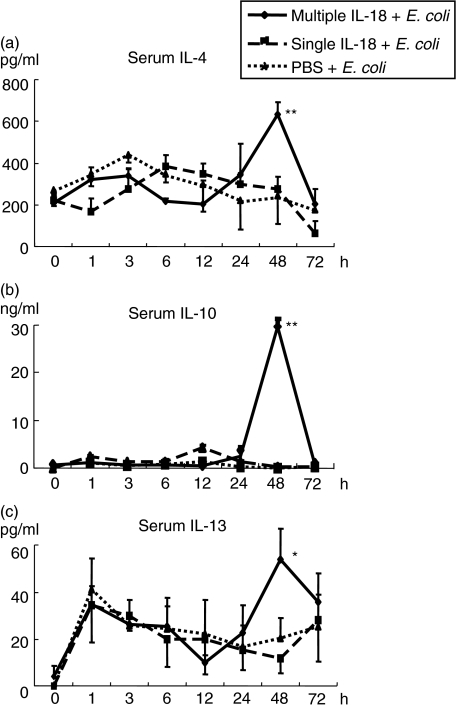

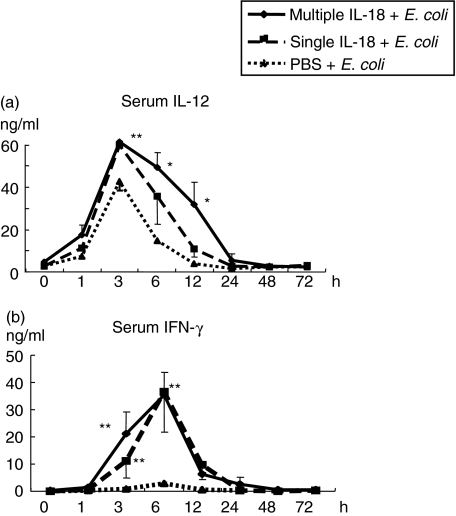

The mice pretreated with multiple IL-18 injections (0·2 µg × 3), a single IL-18 injection (0·2 µg) or PBS injections were challenged i.v. with E. coli. Multiple IL-18 injections increased the serum Th2 cytokine levels of IL-4, IL-10 and IL-13 at 48 h after E. coli challenge significantly more than in the mice with PBS injections. On the other hand, a single IL-18 injection did not exhibit such increases (Fig. 1). In contrast, both multiple and single IL-18 injections increased serum Th1 cytokine (IL-12 and IFN-γ) levels after E. coli challenge (Fig. 2). The mice were also pretreated with a single injection of 0·6 µg of IL-18, which is a total dose of the multiple IL-18 injection regime. These mice did not exhibit any increases in serum Th2 cytokine levels after the E. coli challenge, although they increased serum IFN-γ levels remarkably (data not shown), thus suggesting that the effect of IL-18 on the Th2 cytokine response is time- and not dose-related.

Fig. 1.

Changes in serum Th2 cytokine levels after Escherichia coli challenge in mice pretreated with multiple or single interleukin (IL)-18 injections. The mice were pretreated with multiple IL-18 injections (0·2 µg/mouse, 3 alternate days), a single IL-18 injection (0·2 µg/mouse) or phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) injections, and were then challenged i.v. with E. coli[1 × 108 colony-forming units (CFU)]. The serum cytokine levels [(a) IL-4; (b) IL-10 and (c) IL-13] were measured. The data represent means ± s.e. for seven mice in each group. **P < 0·01, *P < 0·05 versus The group with PBS injections.

Fig. 2.

Changes in serum Th1 cytokine levels after Escherichia coli challenge in mice pretreated with multiple or single interleukin (IL)-18 injections. The pretreated mice were challenged i.v. with E. coli, as described in Fig. 1. The serum levels of (a) IL-12 and (b) IFN-γ were measured. The data represent means ± s.e. for seven mice in each group. **P < 0·01, *P < 0·05 versus The group with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) injections.

IL-18-induced IL-4 and IL-10 were independent of the increase in IFN-γ in the E. coli-challenged mice

To define the effect of IL-18-induced IFN-γ on Th2 cytokines, anti-IFN-γ antibody or goat IgG1 was injected i.v. into the mice that were pretreated with multiple IL-18 injections, and they were then infected with E. coli. The neutralization of IFN-γ did not affect the serum IL-4 or IL-10 levels (data not shown) but it did suppress the increase in serum IL-13 level at 48 h (12·3 ± 7·5 versus 47·9 ± 14·4 pg/ml, P < 0·01). These results suggest that the increase in IL-4 or IL-10 levels is independent of the IFN-γ level while the IL-13 level is either dependent on or related to IFN-γ.

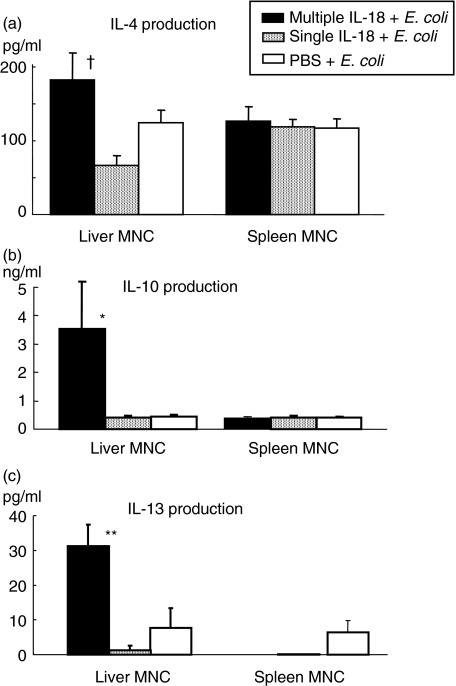

Multiple IL-18 injections increased IL-10 and IL-13 production from liver MNCs in the mice at 48 h after E. coli challenge

Liver and spleen MNCs were obtained at 48 h after E. coli challenge from the mice pretreated with multiple IL-18 injections, a single IL-18 injection or PBS injections. The MNCs were cultured for 24 h and then the cytokine production was compared. Multiple IL-18 injections increased the IL-10 and IL-13 production significantly and also showed higher IL-4 production in liver MNCs compared to the PBS-pretreated control group, although the difference in IL-4 production between the mice with multiple IL-18 injections and mice with a single IL-18 injection was statistically significant (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Cytokine production of liver and spleen mononuclear cells (MNCs) at 48 h after Escherichia coli challenge. The liver and spleen MNCs were obtained from mice pretreated with multiple interleukin (IL)-18, a single IL-18 or PBS injections at 48 h after E. coli challenge. They were then cultured in vitro for 24 h to measure the levels of (a) IL-4, (b) IL-10 and (c) IL-13 in the culture supernatants. The data are means ± s.e. for seven mice in each group. **P < 0·01, *P < 0·05 versus The other two groups, †P < 0·05 versus The group with a single IL-18 injection.

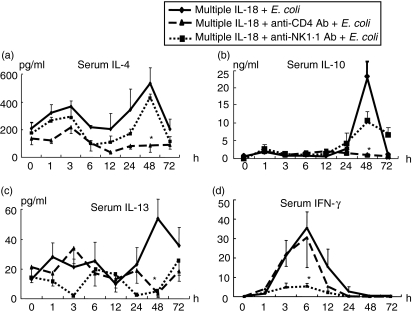

Depletion of CD4+ cells suppressed IL-18-induced Th2 cytokine production in the E. coli-challenged mice

To clarify which cells produce IL-18-induced Th2 cytokines, we depleted CD4+ cells or NK1·1+ cells in the mice using antibodies and then examined any changes in their cytokine profiles after infection. The depletion of CD4+ cells significantly suppressed the serum IL-4, IL-10 and IL-13 levels at 48 h after E. coli challenge. We have reported previously that liver NK cells in the mice pretreated with IL-18 are the main IFN-γ producers in the early phase of the bacterial infection [3,26]. Consistently, the depletion of NK1·1+ cells significantly suppressed serum IFN-γ at 6 h (Fig. 4). Unexpectedly, however, the depletion of NK1·1+ cells also suppressed the serum IL-13 level at 48 h (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Effects of CD4+ or NK1·1+ cell depletion on the changes in serum cytokine levels after Escherichia coli challenge in mice injected with interleukin (IL)-18 multiple times. To deplete CD4+ or natural killer (NK)1·1+ cells, anti-CD4 antibody (500 µg/mouse) or anti-NK1·1 antibody (200 µg/mouse) was injected i.v. into mice that were pretreated with IL-18 multiple times. The mice were then challenged i.v. with E. coli[1 × 108 colony-forming units (CFU)] 3 days after antibody injection. Serum levels of (a) IL-4, (b) IL-10, (c) IL-13 and (d) interferon (IFN)-γ were measured. The data are the means ± s.e. for seven mice in each group. *P < 0·01 versus The group with multiple IL-18 injections (without antibody).

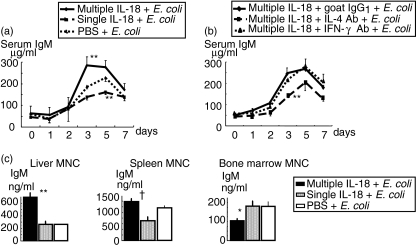

Multiple IL-18 injections increased the serum IgM level in the E. coli-challenged mice

Mice pretreated with multiple IL-18 injections, a single IL-18 injection or PBS injections were challenged i.v. with E. coli. Sera were obtained from the mice immediately before E. coli challenge and 3, 5 and 7 days after E. coli challenge to measure serum immunoglobulin levels. The multiple IL-18 injections significantly increased the serum IgM level 3 days after E. coli challenge compared to the groups with a single IL-18 injection and PBS injections. Interestingly, serum IgM of the single IL-18 injection showed no increase or even lower levels at days 3 and 5 after E. coli challenge than those of the PBS-injected control (Fig. 5a). There was no notable difference in serum IgG1 among these three groups until 7 days (data not shown). The serum IgG2a level increased at 7 days in all groups but no significant difference was observed (not shown).

Fig. 5.

Changes in serum IgM levels after Escherichia coli challenge in mice pretreated with multiple or single interleukin (IL)-18 injections (a). The pretreated mice were challenged i.v. with E. coli[1 × 108 colony-forming units (CFU)], as described in Fig. 1. The data are means ± s.e. for 10 mice in each group. The effects of anti-IL-4 or anti-interferon (IFN)-γ antibody on the serum IgM level of the E. coli- challenged mice that were pretreated with IL-18 multiple times (b). The mice were injected i.v. with anti-IL-4 antibody, anti-IFN-γ antibody or goat IgG1 (control antibody) along with the multiple IL-18 pretreatment at 1 h before E. coli (1 × 108 CFU) challenge. The data are means ± s.e. for five mice in each group. IgM production of the liver, spleen and bone marrow mononuclear cells (MNCs) 3 days after E. coli challenge (c). The mice were challenged i.v. with E. coli, as described in Fig. 1. MNCs were obtained from the organs 3 days after E. coli challenge and were cultured for 24 h to measure IgM in the supernatants. The data are means ± s.e. for seven mice in each group. **P < 0·01, *P < 0·05 versus The other two groups, †P < 0·05 versus The group with a single IL-18 injection.

Neutralization of IL-4 but not IFN-γ suppressed the increased serum IgM level in the E. coli-challenged mice injected multiple times with IL-18

To investigate the effects of IL-4 or IFN-γ on IgM production in mice injected multiple times with IL-18, anti-IL-4 antibody, anti-IFN-γ antibody or goat IgG1 was injected i.v. at 1 h before E. coli challenge and the serum IgM level was then observed. Neutralization of IL-4 significantly suppressed the serum IgM level at 3 days after E. coli challenge, although it did not completely suppress the elevation of IgM (Fig. 5b). On the other hand, neutralization of IFN-γ did not affect the serum IgM level (Fig. 5b).

Multiple IL-18 injections increased IgM production of the mouse liver MNCs at 3 days after E. coli challenge

To define which organ MNCs contribute to IL-18-induced IgM production, MNCs were obtained from the liver, spleen and bone marrow 3 days after E. coli challenge in the mice pretreated with multiple IL-18 injections, a single IL-18 injection and PBS injections, and the cells were then cultured for 24 h. Multiple IL-18 injections increased IgM production from the liver MNCs significantly more than in the other groups, while they did not show a significant increase in IgM production by spleen MNCs compared to the PBS injections, although multiple IL-18 injections significantly increased IgM production by spleen MNCs compared to the single IL-18 injection. In contrast, multiple IL-18 injections significantly decreased the IgM production by bone marrow MNCs compared to the other groups (Fig. 5c).

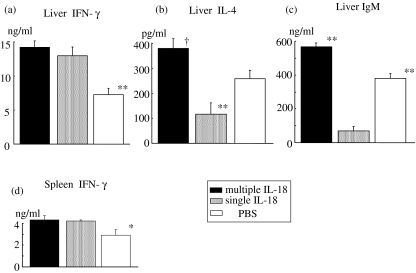

Multiple IL-18 injections caused mouse liver MNCs to increase the production of not only IFN-γ but also Th2 cytokines and IgM by in vitro LPS stimulation, while a single IL-18 injection increased only IFN-γ production of liver MNCs

We examined how IL-18 treatment affects the production of both Th1/Th2 cytokines and IgM from liver MNCs by in vitro LPS stimulation. Liver MNCs were obtained from mice that were treated with multiple IL-18 injections, a single IL-18 injection and PBS injections and were then cultured with LPS for either 48 h to measure the cytokine production, or cultured for 72 h to measure the IgM production. Both multiple and single IL-18 injections significantly increased IFN-γ production from liver MNCs by LPS stimulation more than those of PBS injections (Fig. 6a). Interestingly, multiple IL-18 injections also significantly increased IL-4 and IgM productions from liver MNCs more than those of PBS injections, while conversely a single IL-18 injection decreased such production in comparison to both multiple IL-18 and PBS injections (Figs 6b,c). Consistently, multiple IL-18 injections significantly increased both IL-10 and IL-13 production from liver MNCs by LPS stimulation more than those of the other groups (data not shown). No significant production of IgG1 or IgG2a was detectable in the culture supernatants of liver MNCs in any groups by LPS stimulation for 72 h (not shown). To examine the effects of IL-18 treatment on the spleen MNCs by in vitro LPS stimulation, we also cultured the spleen MNCs with LPS for either 48 h to measure the cytokine production or for 72 h to measure the IgM production. Both multiple and single IL-18 injections significantly increased the IFN-γ production from spleen MNCs by LPS stimulation more than those of PBS injections, although spleen MNCs did not produce a larger amount of IFN-γ than liver MNCs in all groups (Fig. 6d). However, no significant differences in the production of IL-4, IL-10 or IL-13 from spleen MNCs were observed among all groups (data not shown). Although no significant difference was observed among all groups, spleen MNCs did produce a remarkably larger amount of IgM by LPS stimulation than those of liver MNCs in all groups (data not shown).

Fig. 6.

Effect of IL-18 treatment on the production of Th1/Th2 cytokines and IgM from liver and spleen mononuclear cells (MNCs) by in vitro LPS stimulation. Liver and spleen MNCs were obtained from mice that were treated with either multiple interleukin (IL)-18 injections, a single IL-18 injection or phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) injections and were then cultured with 10 µg/ml of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) for either 48 h to measure the (a, d) interferon (IFN)-γ, and (b) IL-4 levels in the supernatants or (c) cultured for 72 h to measure the IgM level. The data are pooled from two or three independent experiments with three to four mice per treatment group. The data are means ± s.e. **P < 0·01, *P < 0·05 versus The other two groups, †P < 0·01 versus The group with a single IL-18 injection and P < 0·05 versus The group with PBS injections.

Discussion

Multiple IL-18 injections into the mice raised the serum IFN-γ level at 6 h and serum Th2 cytokine levels, such as IL-4, IL-10 and IL-13, at 48 h after E. coli challenge while a single IL-18 injection increased only the serum IFN-γ level. A depletion of CD4+ cells suppressed IL-18-induced Th2 cytokines, IL-4, IL-10 and IL-13, while a depletion of NK1·1+ cells reduced the IFN-γ and IL-13 levels. Moreover, multiple IL-18 injections up-regulated the serum IgM level at 72 h after E. coli challenge while a single IL-18 injection did not up-regulate the serum IgM. Interestingly, neutralization of IL-4 but not IFN-γ suppressed the increased serum IgM. Liver MNCs obtained from the multiple IL-18-injected mice without E. coli challenge significantly produced not only IFN-γ but also Th2 cytokines and IgM by in vitro LPS stimulation more than those from the mice with a single IL-18 injection and PBS injections. Multiple IL-18 injections might therefore induce an enhanced production of IFN-γ as well as IgM, particularly in liver MNCs, against Gram-negative bacterial infections via the increased release of Th2 cytokines from hepatic CD4+T cells.

Although IL-18 itself cannot induce strong IFN-γ production, IL-18 induces IFN-γ production synergistically along with IL-12 [1,7,10,31]. In bacterial infections, exogenous IL-18 has been proven to augment IFN-γ production in concert with microbe-induced IL-12 [32]. In fact, the IL-18-injected mice showed increased IFN-γ production following the elevation of IL-12 after E. coli challenge (Fig. 2). However, multiple IL-18 injections but not a single IL-18 injection also increased the Th2 cytokine production unexpectedly after E. coli challenge (Fig. 1). Although several reports have suggested the involvement of IL-18 in the induction of Th2 cytokines and IgE in allergic disorders [12,33], IL-18 has not yet been reported to induce a Th2 immune response accompanied by IgM production after bacterial infections in mice. IgM is thought to act as a first line of defence against microbial infections because it can activate efficiently the classical complement cascade, and it is thereby involved closely in bacteriolysis as well as in neutrophil activation through opsonization [17–21,23,34]. In addition, the surface expression of CD11b on neutrophils, an activation marker, is reduced in IL-18-deficient mice during the course of E. coli peritonitis [35]. In our previous study, multiple IL-18 injections increased strongly the number and proportion of NK cells in mouse liver MNCs before E. coli challenge, while they did not affect the number or proportion of hepatic B cells or CD4+T cells [3,4]. Nevertheless, mice injected with IL-18 multiple times but not with a single injection showed increased production of IL-4, IL-10, IL-13 and IgM after E. coli infection (Figs 1 and 5). These results suggest that B cells with an IgM-producing capacity are primed by repeated IL-18 stimulations before E. coli infection and such primed B cells produce IgM after stimulation with Th2 cytokines, especially IL-4 induced by E. coli infection. Because B cells are capable of switching from IgM-producing cells to IgG or IgE-producing cells [36], it can also be speculated that IL-18-stimulated B cells may possibly differentiate further into either IgG-producing cells or IgE-producing cells, depending upon the types of subsequent stimulations and their cytokine milieu.

The neutralization of IL-4 significantly but not completely inhibited the IL-18-induced IgM production after E. coli challenge (Fig. 5b). Therefore, IL-18 itself or other Th2 cytokines induced by IL-18 may also be needed for enhanced IgM production after E. coli challenge. Yoshimoto et al. reported that IL-18 might induce NK T cells to produce IL-4 [37]. In our case, however, anti-NK1·1 antibody treatment did not inhibit the increase in serum IL-4 level, while the anti-CD4 antibody treatment did (Fig. 4a), thus suggesting that multiple IL-18 injections cause CD4+T cells but not NK T cells to produce IL-4 after E. coli challenge. We have confirmed previously that anti-CD4 antibody did not deplete CD4-expressing liver NK T cells because the CD4 expression level of NK T cells was lower than that of conventional CD4+T cells [38].

Although it is well known that Th1 and Th2 cytokines basically cross-regulate each other's development and activity [39–42], the occurrence of preceding Th1 immune reactions might thereafter possibly induce Th2 immune reactions in the host at bacterial infections, because the host protects against bacterial insult by effectively using both Th1 and Th2 immune reactions [43]. Interestingly, multiple IL-18 injections, however, up-regulated the Th2 immune reaction independent of the existence of any IL-18-induced IFN-γ in the mouse E. coli infection. In addition, liver MNCs that were obtained from the mice injected with IL-18 multiple times increased production of both Th2 cytokines and IgM by in vitro LPS stimulation (Fig. 6). These findings suggest that multiple IL-18 injections can augment Th2 immune reaction in the host against Gram-negative bacterial infection, and thereby the IL-18-induced Th2 reactions are not considered to be simply immunological phenomena that occur after an E. coli infection in mice treated with IL-18.

IL-13 was cloned originally from a murine Th2 cell clone and shares biological functions with IL-4 [44], whereas there is little evidence that IL-13 can directly drive Th2 cell development. In the present study, the neutralization of IFN-γ suppressed IL-13 but not IL-4 or IL-10 in E. coli-challenged mice. Depletion of NK1·1+ cells also suppressed IL-13 as well as IFN-γ, but there was no significant suppression of serum IL-4 (Fig. 4). The initial peak of serum IL-13 level in the early phase of infection may be attributable to the presence of NK cells, because under certain conditions IL-18 may induce IL-13 production from NK cells as well as CD4+T cells [11]. Therefore, the characteristics of IL-13 seem to be quite different from those of IL-4. Wynn has also mentioned the possibility of an IL-4-independent IL-13 production [45]. Unlike IL-4 and IL-10, the production of IL-13 is affected by either a depletion of CD4+T cells or by a depletion of NK/NK T cells (Fig. 4). However, further study is needed to clarify these issues.

Liver MNCs but not spleen MNCs significantly increased production of IFN-γ as well as Th2 cytokines and IgM after the administration of IL-18 during E. coli infection, although spleen MNCs have a large capacity to produce IgM. It has been reported that more than 70% of the bacteria that entered the blood stream accumulate in the liver and are trapped by Kupffer cells as well by hepatocytes [46–48]. Furthermore, hepatocytes produce acute phase proteins and complements, both of which are essential for defence against bacterial infections [48,49]. These findings may explain why liver MNCs respond promptly to bacterial infections and may thus induce both the cellular and humoral innate immunities in the hosts.

These findings lead us to conclude that IL-18 has a novel function by which it enhances not only IFN-γ production from liver NK cells but also IgM production from liver B cells during E. coli infections via the up-regulation of Th2 cytokines.

References

- 1.Okamura H, Tsutsi H, Komatsu T, et al. Cloning of a new cytokine that induces IFN-gamma production by T cells. Nature. 1995;378:88. doi: 10.1038/378088a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nakanishi K, Yoshimoto T, Tsutsui H, Okamura H. Interleukin-18 regulates both Th1 and Th2 responses. Annu Rev Immunol. 2001;19:423. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kinoshita M, Seki S, Ono S, Shinomiya N, Hiraide H. Paradoxical Effect of IL-18 therapy on the severe and mild Escherichia coli infections in burn-injured mice. Ann Surg. 2004;240:313. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000133354.44709.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ami K, Kinoshita M, Yamauchi A, et al. IFN-gamma production from liver mononuclear cells of mice in burn injury as well as in postburn bacterial infection models and the therapeutic effect of IL-18. J Immunol. 2002;169:4437. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.8.4437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nakanishi K. Innate and acquired activation pathways in T cells. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:140. doi: 10.1038/84236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kohno K, Kataoka J, Ohtsuki T, et al. IFN-gamma-inducing factor (IGIF) is a costimulatory factor on the activation of Th1 but not Th2 cells and exerts its effect independently of IL-12. J Immunol. 1997;158:1541. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Robinson D, Shibuya K, Mui A, et al. IGIF does not drive Th1 development but synergizes with IL-12 for interferon-gamma production and activates IRAK and NFkappaB. Immunity. 1997;7:571. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80378-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tsutsui H, Matsui K, Kawada N, et al. IL-18 accounts for both TNF-alpha- and Fas ligand-mediated hepatotoxic pathways in endotoxin-induced liver injury in mice. J Immunol. 1997;159:3961. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yoshimoto T, Takeda K, Tanaka T, et al. IL-12 up-regulates IL-18 receptor expression on T cells, Th1 cells, and B cells: synergism with IL-18 for IFN-gamma production. J Immunol. 1998;161:3400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xu D, Chan WL, Leung BP, et al. Selective expression and functions of interleukin 18 receptor on T helper (Th) type 1 but not Th2 cells. J Exp Med. 1998;188:1485. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.8.1485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoshino T, Wiltrout RH, Young HA. IL-18 is a potent coinducer of IL-13 in NK and T cells: a new potential role for IL-18 in modulating the immune response. J Immunol. 1999;162:5070. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yoshimoto T, Mizutani H, Tsutsui H, et al. IL-18 induction of IgE: dependence on CD4+ T cells, IL-4 and STAT6. Nat Immunol. 2000;1:132. doi: 10.1038/77811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yoshimoto T, Tsutsui H, Tominaga K, et al. IL-18, although antiallergic when administered with IL-12, stimulates IL-4 and histamine release by basophils. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:13962. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.24.13962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Campbell E, Kunkel SL, Strieter RM, Lukacs NW. Differential roles of IL-18 in allergic airway disease: induction of eotaxin by resident cell populations exacerbates eosinophil accumulation. J Immunol. 2000;164:1096. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.2.1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wild JS, Sigounas A, Sur N, et al. IFN-gamma-inducing factor (IL-18) increases allergic sensitization, serum IgE, Th2 cytokines, and airway eosinophilia in a mouse model of allergic asthma. J Immunol. 2000;164:2701. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.5.2701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kumano K, Nakao A, Nakajima H, et al. Interleukin-18 enhances antigen-induced eosinophil recruitment into the mouse airways. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160:873. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.160.3.9805026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barrington R, Zhang M, Fischer M, Carroll MC. The role of complement in inflammation and adaptive immunity. Immunol Rev. 2001;180:5. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2001.1800101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sakamoto M, Fujisawa Y, Nishioka K. Physiologic role of the complement system in host defense, disease, and malnutrition. Nutrition. 1998;14:391. doi: 10.1016/s0899-9007(97)00473-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cooper NR. The classical complement pathway: activation and regulation of the first complement component. Adv Immunol. 1985;37:151. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60340-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brown JS, Hussell T, Gilliland SM, et al. The classical pathway is the dominant complement pathway required for innate immunity to Streptococcus pneumoniae infection in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:16969. doi: 10.1073/pnas.012669199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boes M, Prodeus AP, Schmidt T, Carroll MC, Chen J. A critical role of natural immunoglobulin M in immediate defense against systemic bacterial infection. J Exp Med. 1998;188:2381. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.12.2381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoffmann EM, Houle JJ. Contradictory roles for antibody and complement in the interaction of Brucella abortus with its host. Crit Rev Microbiol. 1995;21:153. doi: 10.3109/10408419509113538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jankowski S. The role of complement and antibodies in the impaired bactericidal activity of neonatal sera against Gram-negative bacteria. Acta Microbiol Pol. 1995;44:5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O'Shea JJ, Paul WE. Regulation of T(H)1 differentiation − controlling the controllers. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:506. doi: 10.1038/ni0602-506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guo L, Hu-Li J, Paul WE. Probabilistic regulation of IL-4 production in Th2 cells: accessibility at the IL4 locus. Immunity. 2004;20:193. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(04)00025-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seki S, Osada S, Ono S, et al. Role of liver NK cells and peritoneal macrophages in gamma interferon and interleukin-10 production in experimental bacterial peritonitis in mice. Infect Immun. 1998;66:5286. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.11.5286-5294.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nakagawa R, Nagafune I, Tazunoki Y, et al. Mechanisms of the antimetastatic effect in the liver and of the hepatocyte injury induced by alpha-galactosylceramide in mice. J Immunol. 2001;166:6578. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.11.6578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ogasawara K, Takeda K, Hashimoto W, et al. Involvement of NK1+ T cells and their IFN-gamma production in the generalized Shwartzman reaction. J Immunol. 1998;160:3522. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dobashi H, Seki S, Habu Y, et al. Activation of mouse liver natural killer cells and NK1.1(+) T cells by bacterial superantigen-primed Kupffer cells. Hepatology. 1999;30:430. doi: 10.1002/hep.510300209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Habu Y, Seki S, Takayama E, et al. The mechanism of a defective IFN-gamma response to bacterial toxins in an atopic dermatitis model, NC/Nga mice, and the therapeutic effect of IFN-gamma, IL-12, or IL-18 on dermatitis. J Immunol. 2001;166:5439. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.9.5439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Munder M, Mallo M, Eichmann K, Modolell M. Murine macrophages secrete interferon gamma upon combined stimulation with interleukin (IL)-12 and IL-18: a novel pathway of autocrine macrophage activation. J Exp Med. 1998;187:2103. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.12.2103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Micallef MJ, Ohtsuki T, Kohno K, et al. Interferon-gamma-inducing factor enhances T helper 1 cytokine production by stimulated human T cells: synergism with interleukin-12 for interferon-gamma production. Eur J Immunol. 1996;26:1647. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830260736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hoshino T, Yagita H, Ortaldo JR, Wiltrout RH, Young HA. In vivo administration of IL-18 can induce IgE production through Th2 cytokine induction and up-regulation of CD40 ligand (CD154) expression on CD4+ T cells. Eur J Immunol. 2000;30:1998. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200007)30:7<1998::AID-IMMU1998>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fearon DT, Locksley RM. The instructive role of innate immunity in the acquired immune response. Science. 1996;272:50. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5258.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weijer S, Sewnath ME, de Vos AF, et al. Interleukin-18 facilitates the early antimicrobial host response to Escherichia coli peritonitis. Infect Immun. 2003;71:5488. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.10.5488-5497.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Coffman RL, Carty J. A T cell activity that enhances polyclonal IgE production and its inhibition by interferon-gamma. J Immunol. 1986;136:949. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yoshimoto T, Min B, Sugimoto T, et al. Nonredundant roles for CD1d-restricted natural killer T cells and conventional CD4+ T cells in the induction of immunoglobulin E antibodies in response to interleukin 18 treatment of mice. J Exp Med. 2003;197:997. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nakagawa R, Inui T, Nagafune I, et al. Essential role of bystander cytotoxic CD122+CD8+ T cells for the antitumor immunity induced in the liver of mice by alpha-galactosylceramide. J Immunol. 2004;172:6550. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.11.6550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mosmann TR, Cherwinski H, Bond MW, Giedlin MA, Coffman RL. Two types of murine helper T cell clone. I. Definition according to profiles of lymphokine activities and secreted proteins. J Immunol. 1986;136:2348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fiorentino DF, Bond MW, Mosmann TR. Two types of mouse T helper cell. IV. Th2 clones secrete a factor that inhibits cytokine production by Th1 clones. J Exp Med. 1989;170:2081. doi: 10.1084/jem.170.6.2081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fitch FW, McKisic MD, Lancki DW, Gajewski TF. Differential regulation of murine T lymphocyte subsets. Annu Rev Immunol. 1993;11:29. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.11.040193.000333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Abbas AK, Murphy KM, Sher A. Functional diversity of helper T lymphocytes. Nature. 1996;383:787. doi: 10.1038/383787a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Trinchieri G. Interleukin-12. a proinflammatory cytokine with immunoregulatory functions that bridge innate resistance and antigen-specific adaptive immunity. Annu Rev Immunol. 1995;13:251. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.13.040195.001343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.de Vries JE. Molecular and biological characteristics of interleukin-13. Chem Immunol. 1996;63:204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wynn TA. IL-13 effector functions. Annu Rev Immunol. 2003;21:425. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Benacerraf B, Sebestyen MM, Schlossman S. A quantitative study of the kinetics of blood clearance of P32-labelled Escherichia coli and Staphylococci by the reticuloendothelial system. J Exp Med. 1959;110:27. doi: 10.1084/jem.110.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gregory SH, Barczynski LK, Wing EJ. Effector function of hepatocytes and Kupffer cells in the resolution of systemic bacterial infections. J Leukoc Biol. 1992;51:421. doi: 10.1002/jlb.51.4.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Seki S, Habu Y, Kawamura T, et al. The liver as a crucial organ in the first line of host defense. the roles of Kupffer cells, natural killer (NK) cells and NK1.1 Ag+ T cells in T helper 1 immune responses. Immunol Rev. 2000;174:35. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0528.2002.017404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Steel DM, Whitehead AS. The major acute phase reactants: C-reactive protein, serum amyloid P component and serum amyloid A protein. Immunol Today. 1994;15:81. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(94)90138-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]