Abstract

Oral administration of proteases such as bromelain and papain is commonly used in patients with a wide range of inflammatory conditions, but their molecular and cellular mechanisms of action are still poorly understood. The aim of our study was to investigate the impact of these proteases on the release of interleukin-6 (IL-6) and other cytokines in the recently described modified mixed lymphocyte culture (MMLC) test system which is based on the mutual interaction of cells of the innate and adaptive immunity. Bromelain and papain enhanced IL-6 production dose-dependently up to 400-fold in MMLC before and up to 30-fold after neutralization of LPS content of proteases using polymyxin B, indicating that IL-6 induction by protease treatment was attributable to both protease action and LPS content of enzyme preparations. The production of IFNγ and IL-10 was not altered by bromelain or papain, indicating a selective and differential immune activation. Both proteases impaired cytokine stability, cell proliferation and expression of cell surface molecules like CD14 only marginally, suggesting no impact of these mechanisms on protease-mediated cytokine release. These findings might provide the mechanistic rationale for the current use of proteases in wound healing and tissue regeneration since these processes depend on IL-6 induction.

Keywords: immunomodulation, IL-6, cytokines, MMLC, proteases

Introduction

Proteases are widely used in systemic enzyme therapy to treat various immune-mediated conditions. Single proteolytic enzymes or enzyme combinations are prescribed and administered orally to alleviate inflammatory symptoms of sport injuries, infections, rheumatoid or autoimmune disorders, sepsis and to support wound healing [1–3]. Most products contain at least one of the two proteases, bromelain and papain. Bromelain and papain are derived from pineapple (Ananas comosus) and papaya (Carica papaya) or other plants, respectively, and have been proposed to act antiedematous, anti-inflammatory, antithrombotic, analgesic and antitumorigenic [1].

Despite their clinical use for several decades, their mechanism of action is still not well understood. It has been reported that protease treatment can induce or enhance release of cytokines as well as nitric oxide from leucocytes in vitro [4–6] and that oral doses of proteases also influence cytokine expression in vivo [7,8]. Protease treatment does however not always entail immune stimulation. Bromelain, a mixture of cysteine proteases, has been shown to interfere with intracellular signal transduction pathways by blocking the activation of extracellular regulated kinase-2 in T cells [9] and to cleave cell surface molecules on human leucocytes that are involved in cell–cell interaction and activation [10,11]. The degradative action has the potential to alter immune cell function since CD2-mediated T cell activation was augmented [10], whereas CD44-mediated lymphocyte binding to human umbilical vein endothelial cells was decreased [11] subsequent to bromelain treatment in vitro. Data from animal studies also suggest that protease action is rather complex and may simultaneously activate, inhibit or modulate lymphocyte function [12–15]. Beyond these preclinical studies, data from clinical trials investigating protease preparations appear inconsistent as to their therapeutic benefit [2].

Our previous work investigated the impact of proteases on autoimmunity and the Th1/Th2 cytokine production by T cells [16]. In order to obtain more mechanistic insights into protease-mediated action, we aimed to characterize and compare the immunomodulatory properties of clinically used enzymes in the modified mixed lymphocyte culture (MMLC) assay, a novel ex vivo assay which is based on the mutual interaction and combined activation of cells of the innate and adaptive immunity [17]. The MMLC system allows the study of stimulatory or inhibitory effects of therapeutic agents on immune mediator production as result of interference with different levels of human immunity. The current study focuses on the cytokines IL-6, IFNγ and IL-10 as main analysis parameters. IL-6 is a pleiotropic cytokine which plays a major role in wound healing and tissue regeneration, i.e. conditions treated with proteases [18]. IFNγ and IL-10 represent Th1 and Th2 reactivities, respectively. In order to elucidate mechanisms of immunomodulation, we complemented the MMLC assay with concomitant experiments on protease-mediated cytotoxicity, effects on cytokine stability and cell surface expression of markers involved in cell activation.

Materials and methods

MMLC culture conditions and reagents

PBMC were isolated from sodium-heparinate whole blood of healthy blood donors. MMLC was performed as described before [17]. Briefly, equal numbers (5 × 105 from each donor) of PBMC from two healthy adult blood donors were mixed and cultured at 450 µl/well in pyrogen-free 48-well culture plates (Falcon, Heidelberg, Germany). LPS from E. coli 026:B6 (Sigma, Taufkirchen, Germany; 3000 endotoxin units/µg as measured by Limulus amebocyte lysate test), proteases (bromelain, 5·4 FIP-E./mg; papain, 4·5 FIP-E./ml; all from Mucos Pharma, Geretsried, Germany) and polymyxin B (Sigma) were added to a final volume of 500 µl. Triplicate cultures were incubated under identical conditions without change of medium for four days at 37 °C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere. The cell viability at the end of the incubation period was controlled by trypan blue dye exclusion test. Culture supernatants were harvested and stored in aliquots at −20 °C until cytokine analysis.

All subjects gave their written informed consent. The study was approved by the local ethic committee.

LAL assay

All proteases used in this study were tested for their endotoxin contents by quantitative Limulus amebocyte lysate assay (Cambrex, Verviers, Belgium) according to the manufacturer's protocol. To exclude any interference of protease activity with the proteolytic cascade of the LAL assay, the proteases were heated (96 °C for 10 min) to abrogate enzyme activity before performing the assay. The heating process did not affect the LPS content of medium controls spiked with 20 pg/ml LPS.

MTT assay

MTT assays were used as combined measure for cell proliferation and cell viability to investigate the cytotoxic potential of proteases at various concentrations in the MMLC system by quantifying mitochondrial dehydrogenase activity. MMLC were set up as described above with the only modification that 20% of cells and cell culture medium were used for cultures in pyrogen-free 96-well plates. After the assay period of four days, MTT (Biomol, Hamburg, Germany) was added to a final concentration of 5 mg/ml and MMLC were incubated for 4 h at 37 °C and 5% CO2. Cell lysis and formazan solubilization were achieved by addition of 100 µl lysis buffer (50% (v/v) dimethyl formamide/20% (w/v) sodium dodecyl sulphate, 0·05 M hydrochloric acid) and gentle shaking of the plates for 15–18 h. The OD as measure for formazan production was determined spectrophotometrically. The OD of wells containing only medium, MTT and lysis buffer served as blank and was substracted from all other OD values. The mean OD of cultures without protease treatment were set as 100% enzyme activity.

Cytokine enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

IL-6 and IL-10 protein concentrations were determined using PeliKine Compact ELISA kits from CLB (Amsterdam, the Netherlands). The IFN ELISA was based on a matched monoclonal antibody pair (Endogen, Woburn, USA) and human recombinant IFN protein (PharMingen, Heidelberg, Germany) as standard. The proteolytic effect of proteases on cytokines was determined by preincubating recombinant cytokines with or without proteases (100 µg/ml) in cell culture medium for 2 h at 37 °C before using these mixtures as ELISA samples. Solutions containing proteases only served as negative controls. Signals for IFNγ and IL-10 were not reduced by the preincubation with bromelain and papain. Bromelain did not affect signals for IL-6, whereas high concentrations of papain lowered detectable IL-6 levels by approx. 50%.

Flow cytometry

The impact of proteases on cell surface molecule expression was measured by incubation of PBMC from different donors with proteases at various concentrations for 2 h at 37 °C and subsequent FACS analysis of adherent and nonadherent cells. Adherent cells were detached nonproteolytically using a 2% lidocaine hydrochloride solution (Xylocain; AstraZeneca, Wedel, Germany) [19]. Control stainings demonstrated that lidocaine treatment did not interfere with detection of cell surface markers. Cells were preincubated with FcBlock (anti-CD16/antiCD32; BD Biosciences, Heidelberg, Germany) in order to block unspecific antibody binding in particular to monocytes/macrophages. The following monoclonal antibodies were used: anti-CD3-FITC, anti-CD4-PerCP, anti-CD11a(LFA-1)-PE, anti-CD14-PerCP, anti-CD28-PE, anti-CD54(ICAM-1)-CyChrome, anti-HLA-DR-FITC (all from BD Biosciences). FACS analyses were performed using a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) and Cell Quest software (BD Biosciences).

Statistical analyses

Cytokine levels determined by ELISA are expressed as mean ± SEM from three independent experiments performed in triplicates using different pairs of PBMC donors unless indicated otherwise. Data were analysed using GraphPad Prism Version 4 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). For mean comparisons, student's unpaired two-tailed t-test or one-way analysis of variance (anova) and an appropriate post test were used as indicated. P-values ≤ 0·05 were considered significant.

Results

MMLC test system

To investigate the modulation of IL-6, IFNγ and IL-10 production by proteases in the MMLC system, we first determined their expression in protease-free cultures. As summarized in Table 1, IL-6 was found at mean concentrations of 0·26 ng/ml after four days in MMLC supernatants in the absence of LPS. The addition of 1 ng/ml LPS led to a 309-fold induction of IL-6. IFNγ was the predominant of the three cytokines in MMLC supernatants without LPS with a mean concentration of 15·9 ng/ml. IFNγ production was enhanced more than sixfold by LPS as described before [17]. IL-10 levels reached mean concentrations of 0·19 ng/ml and 0·11 ng/ml in the absence and presence of LPS, respectively. LPS therefore potently induced IL-6 release and shifted the Th1/Th2 balance in the MMLC system towards Th1.

Table 1.

Expression of IL-6, IFNγ and IL-10 and in MMLC without protease treatment. MMLC was incubated with or without 1 ng/ml LPS in triplicates. After 4 days, cell culture supernatants were harvested and assayed for IL-6, IFNγ and IL-10 by ELISA. Mean cytokine concentrations from three independent experiments are given in ng/ml.

| Cytokine | MMLC w/o LPS | MMLC + LPS | Ratio MMLC + LPS/MMLC w/o LPS |

|---|---|---|---|

| IL-6 | 0·26 ± 0·10 | 47·7 ± 11·3 | 309 ± 180 |

| IFNγ | 15·9 ± 9·3 | 82·3 ± 35·0 | 6·5 ± 1·3 |

| IL-10 | 0·19 ± 0·05 | 0·11 ± 0·03 | 0·6 ± 0·1 |

Modulation of IL-6, IFNγ and IL-10 production by proteases

The proteases bromelain and papain were studied at concentrations of 3, 10 or 30 µg/ml in the MMLC system without and with additional LPS stimulus. The impact of bromelain and papain on cytokine release was comparable. In the LPS-free MMLC, bromelain or papain were found to enhance IL-6 levels in a dose-dependent fashion by mean factors of 396 and 269, respectively, at concentrations of 30 µg/ml (P < 0·05 versus control culture; Fig. 1a,b). IFNγ levels were also elevated by both bromelain and papain at 30 µg/ml, but to a lesser extend than IL-6 (mean factors of 4·8 and 6·4, respectively, P < 0·05; Fig. 1c,d). In contrast, IL-10 production was not affected by proteases (Fig. 1e,f). In LPS-treated MMLC, IL-6, IFNγ and IL-10 production was not modulated by bromelain and papain (data not shown), indicating that the stimulatory effect of proteases depends on activation state of the assay.

Fig. 1.

Modulation of IL-6 (a,b), IFNγ (c,d) and IL-10 (e,f) production by proteases. MMLC was performed in the presence or absence of bromelain (a,c,e) or papain (b,d,f) (concentrations 3, 10 or 30 µg/ml). Supernatants were harvested after 4 days and cytokines were measured by ELISA. Data are shown as mean ± SEM of three independent experiments and were analysed with repeated measures anova and Dunnett post test (*P < 0·05).

Impact of LPS content and polymyxin B treatment of proteases on cytokine release in MMLC

To analyse whether these plant-derived proteases contained considerable amounts of endotoxin, we performed analyses of protease preparations using the Limulus amebocyte lysate (LAL) assay and found that bromelain and papain contained 6·6 pg LPS/1 µg bromelain and 0·3 pg LPS/1 µg papain, respectively. To evaluate the impact of LPS contamination of protease preparations on cytokine release in MMLC assay, we performed control experiments using polymyxin B in order to neutralize LPS. The results shown in Fig. 3 indicate that the increase in IL-6 release by bromelain and papain is attributable to both protease action and low LPS content of the enzyme preparations. In the presence of 10 µg/ml polymyxin B, which was sufficient to eliminate the stimulatory effect of 1 ng/ml LPS, the IL-6 release induced by bromelain and papain was 9·6-fold and 23·3-fold, respectively (Fig. 2a). In contrast, the induction of IFNγ seemed to be completely mediated by LPS content of proteases since the elevation of IFNγ levels was blocked by addition of polymyxin B (Fig. 2b). The release of IL-10 was not altered by untreated or polymyxin B treated proteases (Fig. 2c). This indicates that a substantial part of the IL-6 induction seemed to be attributable to protease activity, whereas LPS-free proteases did not affect Th1 or Th2 reactivity as assed by analysing IFNγ and IL-10.

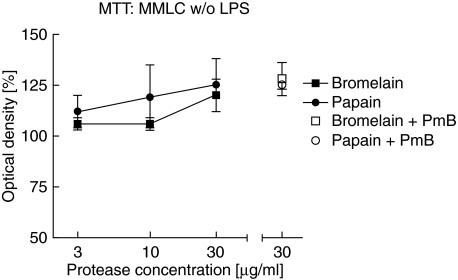

Fig. 3.

MTT assay as combined measure of impact of proteases on cell proliferation and viability in the MMLC system. For MMLC culture, PBMC of two unrelated donors were mixed in equal numbers and incubated with bromelain or papain and with or without polymyxin B (PmB; 10 µg/ml). All cultures were performed in triplicates, MTT was added after 4 days. The mean values ± SD from three independent experiments (two experiments for PmB treated cultures) are shown. Control cultures were set as 100%.

Fig. 2.

Incubation of bromelain, papain or LPS treated MMLC with polymyxin B. MMLC with or without bromelain (B), papain (P) at 30 µg/ml or LPS (1 ng/ml) were cultured in the absence and presence of 10 µg/ml polymyxin B (PmB) during the entire culture period. Supernatants were harvested after 4 days and IL-6 (a), IFNγ (b) and IL-10 (c) were measured by ELISA. Data are shown as mean ± SEM of two independent experiments and were analysed with Students unpaired t-test (*P < 0·05; +P = 0·052 versus protease-free control).

Impact of proteases on cell viability and proliferation

In concomitant experiments, we investigated whether the concentrations of proteases used in our study interfered with cell viability and proliferation in the MMLC system which could result in altered cytokine secretion levels. Cell viability alone as determined by trypan blue exclusion was shown to exceed 90% in all cultures with and without bromelain and papain at concentrations from 3 to 30 µg/ml in the absence or presence of 1 ng/ml LPS (data not shown). In addition, the MTT assay was used as combined measure of cell viability and proliferation. There was no marked difference regarding the impact of proteases on MMLC without LPS (Fig. 3). Cultures with bromelain and papain at concentrations up to 30 µg/ml yielded mean OD values (corresponding to formazan production by mitochondrial dehydrogenase activity) of 100% to 125% compared to protease-free cultures (set as 100%) and therefore showed only minor effects of protease treatment. Polymyxin B did not impair cell viability or proliferation in untreated MMLC (Fig. 3). We rather observed a slight dose-dependent up-regulation of cell activity by proteases independently of LPS activity, which might contribute partly to the effects on cytokine release.

Analysis of cell surface markers

Short-term incubation (2 h) of PBMC with high doses of bromelain and papain (100 µg/ml) was performed to analyse the susceptibility to protease cleavage of several cell surface molecules which play a fundamental role in cell activation by cell-cell contact and LPS binding. Bromelain and papain had comparable effects on cell surface marker expression since they only slightly decreased the expression of CD14 which plays a crucial role in LPS-dependent activation, whereas the expression of other molecules such as CD11a (LFA-1), CD54 (ICAM-1), HLA-DR, CD3, CD4 and CD28 on monocytes and lymphocytes was not affected (data not shown). Incubation with proteases therefore only moderately impaired the expression of certain cell surface proteins, which nevertheless might have important functions in LPS-mediated stimulation.

Discussion

Our study utilizes the novel MMLC test system [17] for the systematic evaluation of the impact on ex vivo cytokine production of two proteases, bromelain and papain, which are most commonly used in systemic enzyme therapy. In previous reports, experiments were often limited to isolated cell types or unphysiologically stimulated lymphocyte cultures treated with high doses of single proteases, usually resulting in protease-mediated increase of cytokine expression [4–6]. The MMLC system represents an ex vivo approach to determine immunomodulatory effects not only on single cell level, but also on the interplay between different kinds of immune cells. The key finding of our experiments is the impact of these proteases on IL-6 release.

In the MMLC system, bromelain and papain increased IL-6 concentrations substantially. The stimulation of IL-6 release might be attributed to proteolytic activation of proteinase-activated receptors (PAR). It has been shown that PAR-2 can be activated by proteases which resulted in up-regulation of IL-6 and other cytokines [20,21], although it should be noted that the IL-6 induction reported here seemed in part also to depend on contaminating LPS of plant-derived bromelain and papain. Given the physiological relevance of IL-6 in infection, inflammation and wound healing, the finding that IL-6 was up-regulated 12- to 30-fold even after neutralization of LPS content by both enzyme preparations might provide a crucial key to the understanding of their mechanism of action and an important rationale for protease treatment. There is ample evidence from studies using IL-6 knock-out mice, that this cytokine has numerous beneficial effects in infection and tissue damage. IL-6 deficiency is associated with enhanced susceptibility to, and diminished clearance of, a wide range of pathogens including extracellular and intracellular bacteria [22–25], parasites [26–28] and fungi [29]. IL-6-deficient mice also exhibit impaired wound healing and tissue regeneration subsequent to injury [30–34], altered nociceptive responses [35] and higher tumour progression [36]. IL-6 exerts pleiotropic effects on different levels of immunity including modulation of cytokine expression, T cell differentiation, immunoglobulin production and leucocyte recruitment which might account for the aforementioned consequences of IL-6 deficiency [18]. Recently, it was shown that IL-6 induces hepcidin in hepatocytes which decreases the availability of iron by inhibition of macrophage iron release and intestinal iron absorption [37]. It can therefore be speculated that IL-6 induction by proteases may be linked with host defence against microorganisms by hepcidin-mediated lowering of serum iron.

In our study, proteases exerted no effects on the balance of Th1 and Th2 reactivities after neutralization of LPS content and only minor effects on cell surface marker expression. The plant-derived enzymes bromelain and papain impair neither the release of the Th1 cytokine IFNγ, nor the levels of the Th2 cytokine IL-10, but augmented IL-6 production as discussed above. A comparable selectivity with more pronounced Th1 inhibition has been reported in two studies focusing on the potential of proteases for therapy of autoimmunity. Our group could show previously that proteases selectively inhibited Th1, but not Th2 cytokine production in an autoreactive T cell clone derived from a patient with type 1 diabetes [16]. Furthermore, oral administration of Phlogenzym (containing bromelain, trypsin and the antioxidant rutoside) resulted in complete prevention from experimental allergic encephalomyelitis (EAE) in a murine model of multiple sclerosis which was paralleled by a shift towards a Th2 cytokine profile [12]. Taken together, these data indicate that proteases (at least bromelain and papain) do not merely act as either stimulatory or inhibitory, but can be used for more subtle interventions. The shift towards Th2 reactivity is interesting since Th1 cytokines are involved in increased vascular leakage and swelling [38], whereas protease preparations are used for the therapy of sports injuries due to their empirically described antiedematous effects. The interference with Th1/Th2 balance as seen in the EAE model in vivo might therefore support beneficial effects of enhanced IL-6 release in the complex processes of wound healing and resolution of local inflammation.

The investigations on cytokine release were complemented by comparative analyses of protease-mediated cleavage of cell surface and soluble molecules which have not been performed in previous studies. The analysis of the effects on cell surface molecule expression differed from our previous approach [16] by incubating PBMC for only two hours in order to detect direct proteolytic cleavage and exclude more complex, cytokine-mediated autocrine and paracrine effects on cellular activation and regulation which would most likely manifest after significantly longer incubation periods. Short-term protease treatment only affected CD14, which mediates LPS stimulation, but not CD4, CD28 and ICAM-1, which are essential for cell-cell contacts between components of innate and adaptive immunity. Nevertheless, proteolysis of these and other, not tested molecules did not impair cell proliferation in the MMLC system even at high concentrations of proteases. Soluble cytokines represent a second layer of cell-cell communication. Although proteolytic cleavage might have reduced IL-6 signal in cultures with high papain concentrations, the resulting increase in IL-6 production would rather have been underestimated. Therefore, the key findings of our study appear not to be influenced by this mechanism.

It is difficult to estimate the physiological impact of oral doses of protease preparations since data on the resorption of macromolecular proteases and bioavailability are limited and inconsistent. Although results from experiments with radiolabelled enzymes and immunological detection methods may vary, the existence of intestinal transport of proteases and subsequently enhanced proteolytic activity in plasma could be demonstrated [39]. Clinical studies analysing the impact of oral protease treatment on IL-6 serum levels are rare and contradictory [40,41]. Further studies are required to reveal if the induction of IL-6 by bromelain in vitro is also present after in vivo Treatment.

Taken together, our findings demonstrate that plant-derived proteases used in systemic enzyme therapy showed strong immunomodulatory effects. In particular, IL-6 release was stimulated very potently by bromelain and papain which proposedly mediates the therapeutic benefit of these enzymes during wound healing and tissue regeneration. The release of IFNγ and IL-10 was not modulated by protease activity, which indicates that proteases can be used for specific and differential immunomodulation.

Acknowledgments

We thank Waltraud Fingberg for excellent technical assistance. We are also indebted to all colleagues in the German Diabetes Center who donated blood for this study. The work was supported by the Federal Ministry of Health and Social Security and the Ministry of Science and Research of the State of North Rhine-Westphalia and by an independent grant of the MUCOS foundation.

References

- 1.Maurer HR. Bromelain: biochemistry, pharmacology and medical use. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2001;58:1234–45. doi: 10.1007/PL00000936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leipner J, Iten F, Saller R. Therapy with proteolytic enzymes in rheumatic disorders. Biodrugs. 2001;15:779–89. doi: 10.2165/00063030-200115120-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shahid SK, Turakhia NH, Kundra M, Shanbag P, Daftary GV, Schiess W. Efficacy and safety of phlogenzym – a protease formulation, in sepsis in children. J Assoc Physicians India. 2002;50:527–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Desser L, Rehberger A. Induction of tumor necrosis factor in human peripheral-blood mononuclear cells by proteolytic enzymes. Oncology. 1990;47:475–7. doi: 10.1159/000226875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Desser L, Rehberger A, Paukovits W. Proteolytic enzymes and amylase induce cytokine production in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells in vitro. Cancer Biother. 1994;9:253–63. doi: 10.1089/cbr.1994.9.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Engwerda CR, Andrew D, Murphy M, Mynott TL. Bromelain activates murine macrophages and natural killer cells in vitro. Cell Immunol. 2001;210:5–10. doi: 10.1006/cimm.2001.1793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Desser L, Rehberger A, Kokron E, Paukovits W. Cytokine synthesis in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells after oral administration of polyenzyme preparations. Oncology. 1993;50:403–7. doi: 10.1159/000227219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Desser L, Holomanova D, Zavadova E, Pavelka K, Mohr T, Herbacek I. Oral therapy with proteolytic enzymes decreases excessive TGF-beta levels in human blood. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2001;47:S10–S15. doi: 10.1007/s002800170003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mynott TL, Ladhams A, Scarmato P, Engwerda CR. Bromelain, from pineapple stems, proteolytically blocks activation of extracellular regulated kinase-2 in T cells. J Immunol. 1999;163:2568–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hale LP, Haynes BF. Bromelain treatment of human T cells removes CD44, CD45RA, E2/MIC2, CD6, CD7, CD8, and Leu 8/LAM1 surface molecules and markedly enhances CD2-mediated T cell activation. J Immunol. 1992;149:3809–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Munzig E, Eckert K, Harrach T, Graf H, Maurer HR. Bromelain protease F9 reduces the CD44 mediated adhesion of human peripheral blood lymphocytes to human umbilical vein endothelial cells. FEBS Lett. 1994;351:215–8. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)00860-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Targoni OS, Tary-Lehmann M, Lehmann PV. Prevention of murine EAE by oral hydrolytic enzyme treatment. J Autoimmun. 1999;12:191–8. doi: 10.1006/jaut.1999.0271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paczek L, Gaciong Z, Bartlomiejczyk I, Sebekova K, Birkenmeier G, Heidland A. Protease administration decreases enhanced transforming growth factor-beta 1 content in isolated glomeruli of diabetic rats. Drugs Exp Clin Res. 2001;27:141–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Engwerda CR, Andrew D, Ladhams A, Mynott TL. Bromelain modulates T cell and B cell immune responses in vitro and in vivo. Cell Immunol. 2001;210:66–75. doi: 10.1006/cimm.2001.1807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Manhart N, Akomeah R, Bergmeister H, Spittler A, Ploner M, Roth E. Administration of proteolytic enzymes bromelain and trypsin diminish the number of CD4+ cells and the interferon-gamma response in Peyer's patches and spleen in endotoxemic balb/c mice. Cell Immunol. 2002;215:113–9. doi: 10.1016/s0008-8749(02)00019-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roep BO, van den Engel NK, van Halteren AG, Duinkerken G, Martin S. Modulation of autoimmunity to beta-cell antigens by proteases. Diabetologia. 2002;45:686–92. doi: 10.1007/s00125-002-0797-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rose B, Herder C, Loffler H, Kolb H, Martin S. Combined activation of innate and T cell immunity for recognizing immunomodulatory properties of therapeutic agents. J Leukoc Biol. 2004;75:624–30. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1003454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Diehl S, Rincon M. The two faces of IL-6 on Th1/Th2 differentiation. Mol Immunol. 2002;39:531–6. doi: 10.1016/s0161-5890(02)00210-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nielsen H. Isolation and functional activity of human blood monocytes after adherence to plastic surfaces: comparison of different detachment methods. Acta Pathol Microbiol Immunol Scand [C] 1987;95:81–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1987.tb00012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dery O, Corvera CU, Steinhoff M, Bunnett NW. Proteinase-activated receptors: novel mechanisms of signaling by serine proteases. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:C1429–C1452. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.274.6.C1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mackie EJ, Pagel CN, Smith R, de Niese MR, Song SJ, Pike RN. Protease-activated receptors: a means of converting extracellular proteolysis into intracellular signals. IUBMB Life. 2002;53:277–81. doi: 10.1080/15216540213469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ladel CH, Blum C, Dreher A, Reifenberg K, Kopf M, Kaufmann SH. Lethal tuberculosis in interleukin-6-deficient mutant mice. Infect Immun. 1997;65:4843–9. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.11.4843-4849.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anguita J, Rincon M, Samanta S, Barthold SW, Flavell RA, Fikrig E. Borrelia burgdorferi-infected, interleukin-6-deficient mice have decreased Th2 responses and increased lyme arthritis. J Infect Dis. 1998;178:1512–5. doi: 10.1086/314448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Williams DM, Grubbs BG, Darville T, Kelly K, Rank RG. A role for interleukin-6 in host defense against murine Chlamydia trachomatis infection. Infect Immun. 1998;66:4564–7. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.9.4564-4567.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khalil A, Tullus K, Bartfai T, Bakhiet M, Jaremko G, Brauner A. Renal cytokine responses in acute Escherichia coli pyelonephritis in IL-6-deficient mice. Clin Exp Immunol. 2000;122:200–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2000.01377.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Suzuki Y, Rani S, Liesenfeld O, et al. Impaired resistance to the development of toxoplasmic encephalitis in interleukin-6-deficient mice. Infect Immun. 1997;65:2339–45. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.6.2339-2345.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gao W, Pereira MA. Interleukin-6 is required for parasite specific response and host resistance to Trypanosoma cruzi. Int J Parasitol. 2002;32:167–70. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7519(01)00322-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bienz M, Dai WJ, Welle M, Gottstein B, Muller N. Interleukin-6-deficient mice are highly susceptible to Giardia lamblia infection but exhibit normal intestinal immunoglobulin A responses against the parasite. Infect Immun. 2003;71:1569–73. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.3.1569-1573.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cenci E, Mencacci A, Casagrande A, Mosci P, Bistoni F, Romani L. Impaired antifungal effector activity but not inflammatory cell recruitment in interleukin-6-deficient mice with invasive pulmonary aspergillosis. J Infect Dis. 2001;184:610–7. doi: 10.1086/322793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gallucci RM, Simeonova PP, Matheson JM, Kommineni C, Guriel JL, Sugawara T, Luster MI. Impaired cutaneous wound healing in interleukin-6-deficient and immunosuppressed mice. FASEB J. 2000;14:2525–31. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0073com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kovalovich K, DeAngelis RA, Li W, Furth EE, Ciliberto G, Taub R. Increased toxin-induced liver injury and fibrosis in interleukin-6-deficient mice. Hepatology. 2000;31:149–59. doi: 10.1002/hep.510310123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lin ZQ, Kondo T, Ishida Y, Takayasu T, Mukaida N. Essential involvement of IL-6 in the skin wound-healing process as evidenced by delayed wound healing in IL-6-deficient mice. J Leukoc Biol. 2003;73:713–21. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0802397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Swartz KR, Liu F, Sewell D, Schochet T, Campbell I, Sandor M, Fabry Z. Interleukin-6 promotes post-traumatic healing in the central nervous system. Brain Res. 2001;896:86–95. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)02013-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gallucci RM, Sloan DK, Heck JM, Murray AR, O'Dell SJ. Interleukin 6 indirectly induces keratinocyte migration. J Invest Dermatol. 2004;122:764–72. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2004.22323.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xu XJ, Hao JX, Andell-Jonsson S, Poli V, Bartfai T, Wiesenfeld-Hallin Z. Nociceptive responses in interleukin-6-deficient mice to peripheral inflammation and peripheral nerve section. Cytokine. 1997;9:1028–33. doi: 10.1006/cyto.1997.0243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Molotkov A, Satoh M, Tohyama C. Tumor growth and food intake in interleukin-6 gene knock-out mice. Cancer Lett. 1998;132:187–92. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(98)00182-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nemeth E, Rivera S, Gabayan V, Keller C, Taudorf S, Pedersen BK, Ganz T. IL-6 mediates hypoferremia of inflammation by inducing the synthesis of the iron regulatory hormone hepcidin. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:1271–6. doi: 10.1172/JCI20945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martin S, Maruta K, Burkart V, Gillis S, Kolb H. IL-1 and IFN-gamma increase vascular permeability. Immunology. 1988;64:301–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Castell JV, Friedrich G, Kuhn CS, Poppe GE. Intestinal absorption of undegraded proteins in men: presence of bromelain in plasma after oral intake. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:G139–G146. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1997.273.1.G139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Paczek L, Kropiewnicka EH, Bartlomiejczyk I, Gradowska L, Heidland A, Wood G. Systemic proteolytic enzyme treatment diminishes urinary interleukin 6 in diabetic patients. Nephron. 2000;84:194–5. doi: 10.1159/000045573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Desser L, Sakalova A, Zavadova E, Holomanova D, Mohr T. Concentrations of soluble tumor necrosis factor receptors, beta2-microglobulin, IL-6 and TNF in serum of multiple myeloma patients after chemotherapy and after combined enzyme-therapy. Int J Immunotherapy. 1997;13:121–30. [Google Scholar]