Abstract

Identification of a broad array of leukaemia-associated antigens is a crucial step towards immunotherapy of haematological malignancies. However, it is frequently hampered by the decrease of proliferative potential and functional activity of T cell clones used for screening procedures. Transfer of the genes encoding the T cell receptor (TCR) α and β chains of leukaemia-specific clones into primary T cells may help to circumvent this obstacle. In this study, transfer of two minor histocompatibility antigen (minor H antigen)-specific TCRs was performed and the feasibility of the use of TCR-transgenic T cells for identification of minor H antigens through cDNA library screening was investigated. We found that TCR-transgenic cells acquired the specificity of the original clones and matched their sensitivity. Moreover, the higher scale of cytokine-production by TCR-transgenic T cells permits the detection of either small amounts of antigen-positive cells or cells expressing low amounts of an antigen. When applied in equal numbers, TCR-transgenic T cells and the original T cell clones produced similar results in the screening of a cDNA library. However, the use of increased numbers of TCR-transgenic T cells allowed detection of minute amounts of antigen, barely discernible by the T cell clone. In conclusion, TCR-transfer generates a large amount of functional antigen-specific cells suitable for screening of cDNA expression libraries for identification of cognate antigens.

Keywords: leukaemia/lymphoma/myeloma, minor HC, T cell receptor (TCR)

Introduction

Allogeneic stem cell transplantation (allo-SCT) is the treatment of choice of many haematological malignancies [1]. Increasingly today, the emphasis in allo-SCT is shifting from the use of radio- and chemotherapy to the administration of allogeneic donor T cells, which recognize minor histocompatibility antigens (minor H antigens). Recognition of these minor H antigens by the donor T cells results in elimination of leukaemic cells, a phenomenon called the graft versus leukaemia (GvL) effect [2]. Because many minor H antigens are expressed ubiquitously, the GvL effect is often accompanied by the destruction of a patient's normal tissues, the graft versus host disease (GvHD), which is a major side-effect of allo-SCT.

In HLA-identical patient–donor combinations the response of donor T cells is directed against minor H antigens [3]. As their identification is a laborious process, which may require some luck, only a small number of minor H antigens have been identified to date. Most known minor H antigens represent Class I-restricted antigens derived from allelic genes. In addition, differential antigen processing and gene deletions have been shown to contribute to minor H antigen-disparity between patient and donor. To exploit fully the potential advantages of immunotherapy directed at minor H antigens, a broad panel of leukaemia-associated minor H antigens is required. However, only few such antigens were characterized and identification of novel antigens still remains a challenge.

Generation of donor T cell clones specifically reactive to patient leukaemic cells is usually the first step in a search for leukaemia-associated antigens. After extensive characterization, T cell clones with a promising pattern of reactivity are used subsequently to identify their cognate antigens through screening of cDNA expression libraries [4] or Epstein–Barr virus (EBV)-transformed lymphoblastoid cell lines (EBV-LCL) from members of CEPH families, followed by genetic linkage analysis [5]. Unfortunately, lengthy in vitro selection and expansion procedures of T cells frequently reduce their potential to produce cytokines and proliferate to an extent that makes them unsuitable as a tool for antigen discovery. This problem may be circumvented by transfer of the genes encoding the α- and β-chains of the T cell receptor (TCR) of the leukaemia-reactive T cell clone into primary T cells, which presents a way to generate a large number of antigen-specific T cells for such screening procedures. Successful redirection of T cells towards tumour-associated and minor H antigens via TCR-transfer has been performed and a fine preservation of the original T cell clone's specificity was found [6–8]. However, a dependence of the sensitivity of transduced T cells on the level of expression of the transferred TCR was reported [9,10]. Therefore, it is unclear whether TCR-transgenic cells may be used for cDNA library screening with the same efficacy as original T cell clones.

In this study we demonstrate for the first time the applicability of TCR-transgenic primary T cells for antigen discovery via cDNA library screening. This method may facilitate broadening of the array of tumour antigens, which is essential for the development of new immunotherapeutic approaches.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

T cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated pooled human AB serum, 100 U/ml penicillin (Gibco, Gaithersburg, MD, USA), 100 µg/ml streptomycin (Gibco) and 5 × 10−5 M β-mercaptoethanol (Merck, Haarlem, the Netherlands) (further called PSβ). T cell clones were restimulated once every 2 weeks in 96-well round-bottomed plates (Nunc, Rochester, NY, USA) with 0·5 × 106 T cells, 1 × 106 irradiated (50 Gy) EBV-LCL and 2 × 106 irradiated (50 Gy) PBMC pooled from three donors per plate in the presence of 300 IU/ml interleukin (IL)-2 (Proleukin, Chiron, Amsterdam, the Netherlands) and 1 µg/ml phytohaemagglutinin (Murex Diagnostics, Dartford, UK). One week after stimulation, T cells were harvested and cultured for 1 week at 0·5–1 × 106 cells/ml in the presence of 300 IU/ml IL-2. Five–seven days after harvesting T cells were used for functional assays. The amphotropic Phoenix packaging cell line and the 293-EBNA-B7 cell line were cultured in Dulbecco's minimum essential medium (DMEM) medium (Invitrogen), supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS) (Integro BV, Leuvenheim, the Netherlands) and PSβ.

Cloning of T cell receptors

Use of variable regions of TCRα (AV) and TCRβ (BV) chains in T cell clones was analysed by reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) using forward primers specific for different AV and BV gene families; an oligonucleotide specific for either Cα or Cβ was used as a reverse primer [11]. Full-length sequences of TCR chains were amplified by PCR on the random-primed cDNA of corresponding T cell clones. YKIII.8 TCRα (AV17∼AJ44∼AC, according to the IMGT nomenclature, http://imgt.cines.fr/textes/IMGTrepertoire/index.html) was amplified with primers 5′-CCC GTC GAC ATG GAA ACT CTC CTG GGA G-3′ and 5′-CCC GCG GCC GCC CTC AGC TGG ACC ACA GC-3′ (TCRAC-reverse) and cloned into BamHI and NotI sites of the pMX-mTCRα-IRES-EGFP vector. YKIII.8 TCRβ (BV13∼BJ1-6*02∼BC1) was amplified with primers 5′-GGG CCG CGG ATG CTT AGT CCT GAC CTG CCT GAC-3′ and 5′-CCC GTC GAC TCC TAA CTC CAC TTC CAG-3′, blunted with the Klenow fragment of DNA polymerase I (Invitrogen) and cloned into blunt BamHI and SalI sites of pMX-mTCRα-IRES-EGFP vector. The YKII.39 TCRα (AV9-2*02∼AJ42∼AC) was amplified with primers 5′-TTT GGA TCC GCC CAC CAT GAA CTA TTC TC-3′ and TCRAC-reverse and cloned into BamHI and NotI sites of the pMX-mTCRα-IRES-EGFP vector. YKII.39 TCRβ type could not be found in previous experiments; therefore it was amplified with a common primer 5′-CCC GTC GAC ATG GGY HSC DGB CTC CTM TG-3′, where Y = C + T, H = A + T + C, S = C + G, D = A + T + G, B = T + C + G, M = A + C, and a primer 5′-TTT GCG GCC GCT CAG AAA TCC TTT CTC-3′. The PCR product was cloned into SalI and NotI sites of the pEGFP-N1 vector (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA, USA). Sequencing of the insert revealed the BV5-5*02∼BD2∼BJ2-1∼BC2 type of TCRβ. Then PCR was performed with primers 5′-TTT CCG CGG CCA CCA TGG GCC CTG GGC TC-3′ and 5′-CCG TCG ACC TAG CCT CTG GAA TCC TTT CTC TTG ACC-3′, the PCR product was blunted and cloned into blunt BamHI and SalI sites of the pMX-mTCRα-IRES-EGFP vector. In further experiments the EGFP marker in the pMX-TCRα-IRES-EGFP was substituted with the NGFR marker gene by excising EGFP with NcoI and SalI and sequential cloning of NGFR fragment 26–844 into NcoI and SalI sites and then NGFR fragment 1–25 into the NcoI site. The sequence of all cloned TCR genes was verified with the BigDye Terminator verdsion 3·1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems, Capelle, the Netherlands).

T cell transduction

Retroviral vectors were transfected into the amphotropic Phoenix packaging cell line with the calcium-phosphate precipitation method (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Viral supernatants were harvested on the second and third days after transfection. Donor phytohaemagglutinin (PHA) blasts, obtained by stimulation of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) with 1 µg/ml phytohaemagglutinin (Murex Diagnostics, Dartford, UK) and 300 IU/ml IL-2 (Chiron) in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 5% FCS and PSβ 2 days before the transduction, were transduced in non-treated flasks (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). These flasks were coated with 12·5 µg/ml retronectin (Takara, Otsu, Shiga, Japan) for 2 h, blocked with 2% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 1 h, washed twice with PBS and incubated with retroviral supernatant for 1 h. Cells were added at a concentration of 1 × 106 cells/ml in the culture medium, supplemented with 300 IU/ml IL-2. Fresh viral supernatant was added on the second day. On the third day, cells were harvested and resuspended in fresh medium with addition of 300 IU/ml IL-2. Two days after harvesting, the fraction of transduced cells was determined by flow cytometry.

Transduced T cells were washed in PBS supplemented with 0·5% BSA and 2 mM ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA) (further called MACS buffer). Twenty µl of the diluted monoclonal antibodies (mAb) were added per 1 × 106 cells and incubation at 4°C for 15 min was performed. Cells were washed once in MACS buffer; 20 µl of goat-anti-mouse IgG microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) were added per 107 cells and incubated for 10 min at 4°C. Cells were washed in MACS buffer and separated on a MS MACS column according to the manufacturer's protocol (Miltenyi Biotec). Then a fraction of the sorted cells was incubated with a goat-anti-mouse Ig FITC-conjugated antibody to determine the purity of the selected population by flow cytometry.

Cytokine production assay

Target cells (3 × 104) were co-cultured with 3 × 104 T cells in 96-well round-bottomed plates in duplicate. After 24 h the supernatant was harvested and the interferon (IFN)-γ concentration was measured by the PeliPair human IFN-γ enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) reagent set (CLB, Amsterdam, the Netherlands) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Other human cytokines were measured by a multiplex cytokine assay system (Bio-Plex, Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA) with simultaneous detection of multiple human cytokines in a single sample. Data analysis was performed with Bio-Plex Manager software (Bio-Rad Laboratories) with a five-parametric-curve fitting.

Peptide titration assays

The TIRYPDPVI peptide of RPS4Y was synthesized by solid-phase peptide synthesis and characterized by mass spectrometry (Pepscan Systems, Lelystad, the Netherlands). Endogenous peptides were eluted from the surface of EBV-LCL of donor origin (EBVd) by treatment with an ice-cold citric acid-Na2HPO4 buffer (pH 3·2) for 90 s. Then EBVd were washed twice with RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 2% FCS and incubated overnight in serum-free RPMI-1640 with the peptide at decreasing concentrations. The following day peptide-loaded EBVd were tested for their ability to induce IFN-γ production by YKIII.8.

Screening of the cDNA library

293-EBNA-B7 cells transduced with HLA-B*5201 were plated in flat-bottomed 96-well plates (4 × 104 cells per well). Next day they were transfected in duplicates with 1·5 µl Lipofectamine (Invitrogen) and 100 ng of the DNA isolated from pools of the cDNA library, containing approximately 50 individual clones [12]. After 24 h the culture medium was substituted for 200 µl of RPMI-1640 with 10% human serum (HS) containing 5 × 103 YKIII.8 TCR-transgenic T cells per well. After another 24 h culture supernatant was harvested and IFN-γ production was measured by ELISA.

Results and discussion

Sensitivity of antigen recognition by TCR-transgenic T cells

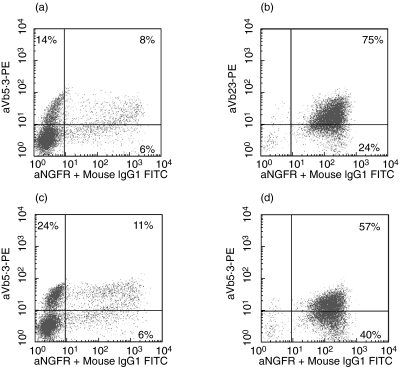

The TCRα and TCRβ chains of two minor H antigen-specific T cell clones were cloned. T cell clone YKIII.8 recognizes the HLA-B*5201-restricted epitope TIRYPDPVI of the H-Y antigen RPS4Y [12]. T cell clone YKII.39 is specific for the peptide MQQMRHKEV of another H-Y antigen UTY, which is also presented in the context of HLA-B*5201 [13]. Both clones had been obtained by stimulation of T cells from an HLA-identical female donor with the male patient's haematopoietic cells and they specifically recognized EBV-LCL of patient origin (EBVp). TCR derived from YKIII.8 (TCRYKIII.8) and YKII.39 (TCRYKII.39) were transferred into T cells of donor origin. After immunomagnetic purification populations of 75% and 57% TCR-transgenic cells were obtained, respectively (Fig. 1). The resulting TCR-transgenic T cells displayed specific reactivity towards the patient's EBV-LCL (Fig. 2), while no specific reactivity was observed against EBV-LCL of donor origin (EBVd), a pattern similar to that of the original clones.

Fig. 1.

Generation and purification of T cell receptor (TCR)-transgenic T cells. FACS-analysis of donor T cells transduced with TCRRPS4Y (a, b) or TCRUTY (c, d) before (a, c) and after (b, d) purification of NGFR + cells with paramagnetic beads. The y-axis shows Vβ gene expression, the x-axis shows NGFR-expression (Vα).

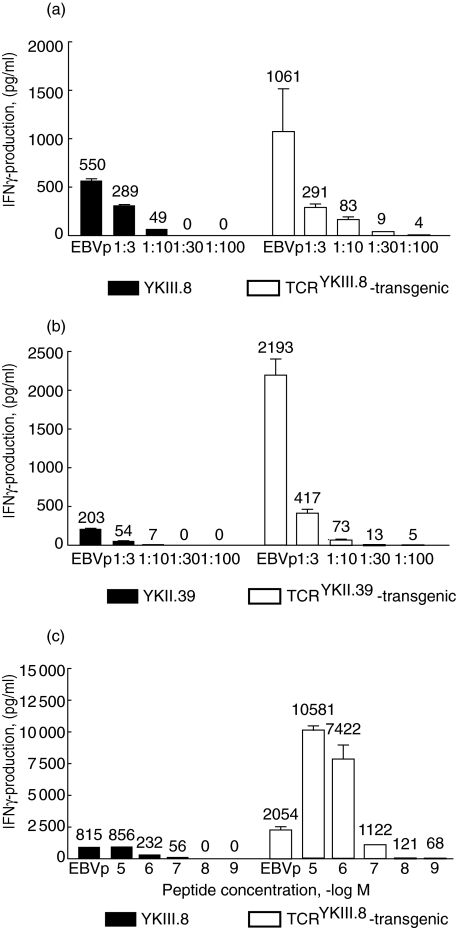

Fig. 2.

T cell receptor (TCR)-transgenic T cells are superior to T cell clones in their sensitivity and the amplitude of interferon (IFN)-γ response. (a) Reactivity of the YKIII.8 T cell clone and TCRYKIII.8-transgenic T cells towards decreasing amounts of EBV-LCL of patient origin (EBVp) was tested in an interferon (IFN)-γ enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). EBVp were progressively diluted with EBVd to achieve the presence of 3 × 104 target cells in each well. (b) The same experiment was performed with the YKII.39 T cell clone and TCRYKII.39-transgenic T cells. (c) An IFN-γ ELISA was used to measure IFN-γ production by YKIII.8 and TCRYKIII.8-transgenic T cells in response to stimulation with EBVd loaded with decreasing (10−5–10−9 M) concentrations of the TIRYPDPVI peptide. As controls, both cell populations were tested against EBVp (first bars for each cell type).

Identification of T cell antigens through cDNA library screening generally involves transfection of pools of 50–100 plasmids together with a plasmid encoding the appropriate HLA-molecule into recipient cells, such as 293 or COS. As a consequence, at best only a fraction of cells will express both HLA and the antigen. Therefore, for efficient use in cDNA library screening procedures, TCR-transgenic T cells should possess not only the specificity, but also the same (if not higher) sensitivity as the original clone, because recognition of minute amounts of antigen is crucial in this approach. Therefore, we compared the reactivity of YKIII.8, YKII.39 and donor T cells transgenic for TCRYKIII.8 and TCRYKII.39 towards decreasing amounts of antigen-positive cells (Fig. 2). EBVp (male antigen-positive B*5201-positive EBV-LCL) were diluted with EBVd (HLA-identical female antigen-negative EBV-LCL) to achieve target cell populations with the fraction of EBVp ranging from 100% to 1%. Remarkably, the amount of IFN-γ produced by TCR-transgenic T cells in response to antigen encounter was, in general, much higher compared to that produced by the original T cell clones YKIII.8 and YKII.39. Moreover, while a minimal ratio of 1: 10 was required for a detectable response by both T cell clones, TCR-transgenic T cells produced IFN-γ in amounts above the background in response to stimulation with 1: 30 diluted EBVp. Although this level may seem low, in practice it is discriminated easily from the background in screenings in a 96-well format.

Furthermore, not only the low percentage of antigen-positive cells but also the low amount of antigen presented on the cell surface may be an obstacle for the cDNA library screening. Hence, we explored the minimal requirements for epitope density on the target cell surface necessary for activation of YKIII.8 and TCRYKIII.8-transgenic T cells. The reactivity towards EBVd loaded with decreasing amounts of the peptide TIRYPDPVI was measured (Fig. 2c). In addition to the overall increased scale of IFN-γ production by TCRYKIII.8-transgenic T cells, their activity was detectable in response to EBVd incubated in the presence of 10−8 M of peptide, while YKIII.8 did not show any activity at this concentration. Taken together, these data prove that the sensitivity of TCR-transgenic T cells is equal or superior to that of the original clones.

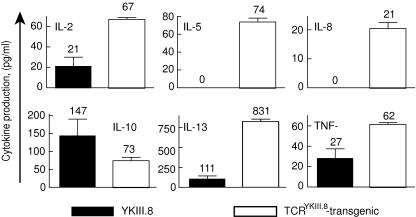

Additionally, secretion of several other cytokines was significantly up-regulated in TCR-transgenic T cells (Fig. 3). This permits the use of read-out systems other than the IFN-γ ELISA, if necessary. Of 12 cytokines tested, five were undetectable or produced at very low levels by both YKIII.8 and TCRYKIII.8-transgenic T cells (IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-4, IL-6, IL-12). Six cytokines were produced in higher concentrations by TCR-transgenic T cells (IL-2, IL-5, IL-8, IL-13, TNF-α, IFN-γ), and IL-10 was the only cytokine that was secreted mainly by the T cell clone.

Fig. 3.

T cell receptor (TCR)-transgenic T cells produce higher amounts of various cytokines compared to the original clones. The multiplex cytokine assay system was used to measure cytokine production by 3 × 103 cells of either YKIII.8 or TCRYKIII.8-transgenic T cells in response to overnight stimulation with 3 × 104 EBV-LCL of patient origin (EBVp). Average results for duplicate measurements and their standard deviations are shown only for those cytokines, which were present in detectable concentrations in at least one of the samples.

Applicability of TCR-transgenic T cells for cDNA library screening

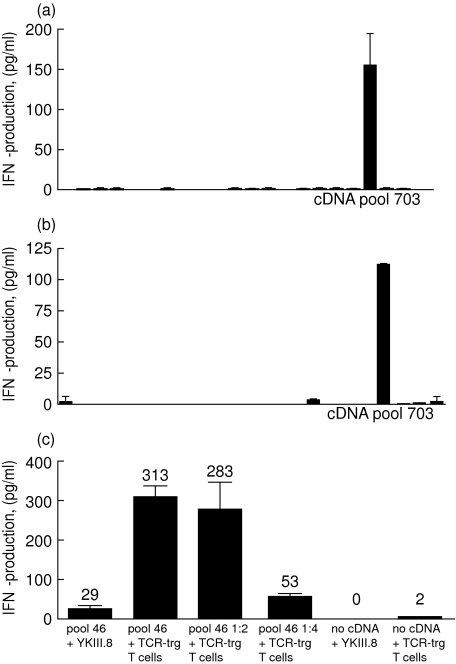

To demonstrate the feasibility of cDNA library screening with genetically engineered T cells we investigated the reactivity of TCRYKIII.8-transgenic T cells towards B*5201-positive 293-EBNA cells transfected with plasmid pools from the EBVp cDNA library. Previously, using YKIII.8 cells in the same protocol we succeeded in identification of the RPS4Y protein as a target of the YKIII.8 response [12]. Transfection of pool 703 into 293-EBNA cells led to the activation of YKIII.8 (Fig. 4). Subcloning of the pool led to isolation of the RPS4Y cDNA. Use of TCRYKIII.8-transgenic T cells produced very similar results (Fig. 4b). Notably, despite the diverse repertoire of TCRYKIII.8-transgenic T cells, none of the 21 RPS4Y-negative cDNA pools induced significant background activation of these cells. Nevertheless, the possibility of T cell activation through its endogenous TCR upon encounter with an irrelevant antigen present in the cDNA library should be taken into consideration. In that case, repeating screening of positive cDNA pools with the original T cell clone may be an option. However, considering the low number of T cells with any single specificity compared to the number of T cells with the redirected specificity, the response towards an irrelevant antigen will probably be very low. Therefore, frequent false-negative results are unlikely. Alloreactivity of TCR-transgenic T cells towards HLA molecules expressed by 293 cells did not cause significant background in our experiments. This may be explained by low expression of endogenous HLA molecules on this cell line. However, alloreactivity of polyclonal TCR-transgenic T cells may prevent their use for screening of immunogenic CEPH EBV-LCL lines (data not shown). Generation of TCR-transgenic clones instead of bulk cultures may be more appropriate for that approach.

Fig. 4.

T cell receptor (TCR)-transgenic T cells are specific and sensitive tools for cDNA library screening. 3 × 103 YKIII.8 (a) or 3 × 103 TCRYKIII.8-transgenic T cells (b) were co-cultured overnight with HLA-B*5201+ 293-EBNA cells transfected with cDNA pools 685–706 from the Epstein–Barr virus of patient origin (EBVp) cDNA library. Interferon (IFN)-γ production was measured with an IFN-γ enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). (c) HLA-B*5201+ 293-EBNA cells were transfected with either undiluted cDNA pool 46 from the EBVp cDNA library or its 1: 2 and 1: 4 dilutions. Reactivity of 3 × 103 YKIII.8 or 3 × 104 TCRYKIII.8-transgenic T cells towards transfected and non-transfected cells was measured in an IFN-γ ELISA.

As shown in Fig. 4, pool 703 induced a high IFN-γ production by YKIII.8, which was not surpassed by TCRYKIII.8-transgenic T cells. However, increasing amounts of effector cells in the assay may augment further the amplitude of the IFN-γ response. Unlike poorly growing T cell clones, TCR-transgenic T cells can be generated in almost any numbers. With buffy coats or leukapheresis products one can begin with, and consequently generate, almost any cell number required. In addition, expansion of TCR-transgenic T cells through stimulation via CD3 and CD28 permits an almost infinite expansion of T cells [14]. Therefore, in the next experiment we investigated whether the use of increased numbers of TCR-transgenic T cells may improve the sensitivity of the cDNA library screening. B*5201-positive 293-EBNA cells were transfected with serial dilutions of cDNA pool 46, which induced a low-level IFN-γ production by YKIII.8 compared to pool 703 and contained a low amount of RPS4Y cDNA (data not shown). When a 10-fold larger amount of TCRYKIII.8-transgenic T cells was used, we could detect the presence of the antigen in the cDNA pool diluted up to fourfold (Fig. 4).

Notably, TCR-transfer on primary donor T cells offers a number of advantages compared to TCR reconstitution on Jurkat cells proposed by Aarnoudse et al. [15]. First, TCR-transgenic T cells are fully functional in terms of cytokine production, permitting the use of ELISA-based screening assays with their high throughput potential, sensitivity and specificity. Moreover, use of Jurkat cells transfected with the NFAT-luciferase reporter construct leads to the increased risk of false-negative results due to the high background of the assay [15]. Next, the greater sensitivity of TCR-transgenic primary T cells is evident from the fact that Jurkat cells recognized melanoma cell lines only after enhancement of the antigen amount on target cells or transduction of Jurkat cells with CD8α. Lastly, the cytolytic activity of TCR-transgenic cells towards various cell types enables the characterization of clinically relevant consequences of recognition of a certain antigen even in case of growth arrest of the original T cell clone.

In conclusion, TCR-transfer into primary T cells not only holds promise as a great therapeutic modality, but also represents a powerful tool in antigen discovery. In this study we have demonstrated for the first time the feasibility of using TCR-transgenic T cells for identification of T cell antigens. TCR-transgenic T cells represent a specific and sensitive tool for antigen discovery through cDNA library screening. Importantly, the use of TCR-transgenic T cells facilitates screening procedures, as large amounts of antigen-specific T cells can be generated in several days. In contrast, expansion of individual T cell clones frequently requires weeks and months of repetitive stimulations, which leads to the proliferative senescence of T cells and a decrease in their functional activity. We anticipate that application of TCR transfer may significantly increase the pace of identification of new prospective immunotherapy targets, which in turn should facilitate introduction of immunotherapeutic approaches into the clinical routine.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Dr Pierre G. Coulie and Dr Benoit van den Eynde (Institute of Cellular Pathology, Université de Louvain, Brussels, Belgium) for the 293-EBNA-B7 cell line; Dr Ton N. M. Schumacher (Netherlands Cancer Institute, Amsterdam, the Netherlands) for the pMX vector; and Dr Garry Nolan (Stanford University, Palo Alto, CA, USA) for the amphotrophic packaging cell line Phoenix.

References

- 1.Champlin R, Gale RP. Bone marrow transplantation: its biology and role as treatment for acute and chronic leukemias. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1987;511:447–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1987.tb36275.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Antin JH. Graft-versus-leukemia: no longer an epiphenomenon. Blood. 1993;82:2273–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spierings E, Wieles B, Goulmy E. Minor histocompatibility antigens − big in tumour therapy. Trends Immunol. 2004;25:56–60. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2003.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dolstra H, Fredrix H, Maas F, et al. A human minor histocompatibility antigen specific for B cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Exp Med. 1999;189:301–8. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.2.301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Akatsuka Y, Nishida T, Kondo E, et al. Identification of a polymorphic gene, BCL2A1, encoding two novel hematopoietic lineage-specific minor histocompatibility antigens. J Exp Med. 2003;197:1489–500. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stanislawski T, Voss RH, Lotz C, et al. Circumventing tolerance to a human MDM2-derived tumor antigen by TCR gene transfer. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:962–70. doi: 10.1038/ni1001-962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heemskerk MH, Hoogeboom M, de Paus RA, et al. Redirection of antileukemic reactivity of peripheral T lymphocytes using gene transfer of minor histocompatibility antigen HA-2-specific T-cell receptor complexes expressing a conserved alpha joining region. Blood. 2003;102:3530–40. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-05-1524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schaft N, Willemsen RA, de Vries J, et al. Peptide fine specificity of anti-glycoprotein 100 CTL is preserved following transfer of engineered TCR alpha beta genes into primary human T lymphocytes. J Immunol. 2003;170:2186–94. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.4.2186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cooper LJ, Kalos M, Lewinsohn DA, Riddell SR, Greenberg PD. Transfer of specificity for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 into primary human T lymphocytes by introduction of T-cell receptor genes. J Virol. 2000;74:8207–12. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.17.8207-8212.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roszkowski JJ, Yu DC, Rubinstein MP, McKee MD, Cole DJ, Nishimura MI. CD8-independent tumor cell recognition is a property of the T cell receptor and not the T cell. J Immunol. 2003;170:2582–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.5.2582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arden B, Clark SP, Kabelitz D, Mak TW. Human T-cell receptor variable gene segment families. 1995. pp. 455–500. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Ivanov R, Aarts T, Hol S, et al. Identification of a 40S ribosomal protein S4-derived H-Y epitope able to elicit a lymphoblast-specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte response. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:1694–703. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ivanov R, Hol S, Aarts T, Hagenbeek A, Slager EH, Ebeling S. UTY-specific TCR-transfer generates potential graft-versus-leukaemia effector T cells. Br J Haematol. 2005;129:392–402. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05461.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kalamasz D, Long SA, Taniguchi R, Buckner JH, Berenson RJ, Bonyhadi M. Optimization of human T-cell expansion ex vivo using magnetic beads conjugated with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 antibodies. J Immunother. 2004;27:405–18. doi: 10.1097/00002371-200409000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aarnoudse CA, Kruse M, Konopitzky R, Brouwenstijn N, Schrier PI. TCR reconstitution in Jurkat reporter cells facilitates the identification of novel tumor antigens by cDNA expression cloning. Int J Cancer. 2002;99:7–13. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]