Abstract

Mechanisms responsible for the induction of anti-nuclear autoantibodies (ANA) following exposure of the immune system to an excess of apoptotic cells are incompletely understood. In this study, the immunogenicity of late apoptotic cells expressing heterologous or syngeneic forms of La/SS-B was investigated following subcutaneous administration to A/J mice, a non-autoimmune strain in which the La antigenic system is well understood. Immunization of A/J mice with late apoptotic thymocytes taken from mice transgenic (Tg) for the human La (hLa) nuclear antigen resulted in the production of IgG ANA specific for human and mouse forms of La in the absence of foreign adjuvants. Preparations of phenotypically healthy cells expressing heterologous hLa were also immunogenic. However, hLa Tg late apoptotic cells accelerated and enhanced the apparent heterologous healthy cell-induced anti-La humoral response, while non-Tg late apoptotic cells did not. Subcutaneous administration of late apoptotic cells was insufficient to break existing tolerance to the hLa antigen in hLa Tg mice or to the endogenous mouse La (mLa) antigen in A/J mice immunized with syngeneic thymocytes, indicating a requirement for the presence of heterologous epitopes for anti-La ANA production. Lymph node dendritic cells (DC) but not B cells isolated from non-Tg mice injected with hLa Tg late apoptotic cells presented immunodominant T helper cell epitopes of hLa. These studies support a model in which the generation of neo-T cell epitopes is required for loss of tolerance to nuclear proteins after exposure of the healthy immune system to an excess of cells in late stages of apoptosis.

Keywords: apoptosis, autoantibodies, autoimmunity, mice, tolerance

Introduction

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a complex autoimmune disorder that can manifest as a range of diverse clinical and serological features, the most unifying of which is the presence of anti-nuclear autoantibodies (ANA) that occur in approximately 95% of individuals diagnosed with the disease [1]. IgG antibodies to the physically associated La/SS-B and Ro/SS-A antigens occur in as many as 30% of SLE patients, where they are most often seen together [2]. Anti-La and -Ro antibodies are pathogenic for infants born to mothers having these specificities, where they deposit in the developing heart, resulting in congenital complete heart block [3, 4]. Although a stronger prevalence of antibodies to La and Ro occurs in individuals suffering from Sjögren's syndrome, where nearly 90% of patients produce antibodies to these proteins [2], it is not clear if these autoantibodies are pathogenic or epigenetic in this setting. Recent evidence suggests that specific ANA occur before precipitation of disease in SLE, indicating that specific autoantibodies are not simply a consequence of autoimmune tissue pathology [5]. Interestingly, autoantibodies to Ro and La are frequently the earliest specificities detected prior to diagnosis of SLE, highlighting the importance of understanding how tolerance becomes lost to these particular proteins [5].

The underlying mechanisms responsible for loss of tolerance to nuclear antigens in SLE are likely to involve genetically encoded defects in immune tolerance pathways, generation of immunity to cryptic or modified self- and impaired clearance of apoptotic cells. The observation that under certain circumstances nuclear antigens are concentrated in membrane blebs that are generated at the surface of apoptotic cells led to the notion that apoptotic cells might serve as nuclear immunogen for the production of ANA [6]. Normally, apoptotic cells and their contents are cleared rapidly and effectively by phagocytes, particularly macrophages [7]. Several in vitro studies have suggested that phagocytosis of apoptotic cells by macrophages is anti-inflammatory [8, 9] and show that syngeneic cells, even in the late stages of apoptosis, fail to mature dendritic cells (DC) [10, 11] and can even inhibit the maturation of DC [12, 13]. Despite this, however, defective clearance of apoptotic cells in vivo enhances the development of ANA and lupus-like illness in mice having autoimmune-prone backgrounds [14, 15]. Indeed, there is evidence supporting defective apoptotic cell clearance in human SLE [16, 17]. Mechanistically, it has been proposed that under conditions of defective clearance, apoptotic cells become necrotic, release their intracellular contents and promote immunity rather than tolerance [17]. Moreover, modifications to intracellular antigens during apoptosis, such as proteolytic cleavages [18, 19], oxidation [6], citrullination or changes in phosphorylation or acetylation status [20] are likely to reveal autoimmunity-inducing cryptic T and/or B cell epitopes to which tolerance has not been established previously.

In the current study, we employed a human La (hLa) transgenic (Tg) mouse model [21] to determine the importance of heterologous epitopes that mimic apoptosis-induced neo-epitopes in the generation of anti-La immunity in the context of late apoptotic cells. The results indicate that an excess of late apoptotic cells containing known heterologous neo-T cell epitopes [21] are immunogenic in vivo in a non-autoimmune mouse strain. DC but not B cells from lymph nodes (LN) draining the injection site presented immunodominant T cell epitopes of the hLa protein. In contrast, syngeneic cells in late apoptosis failed to break tolerance to the La nuclear antigen in a model governed by a single murine H-2 haplotype. Moreover, given a non-autoimmune genetic background, these data suggest that the generation of neo-epitopes is necessary for loss of tolerance to a clinically relevant nuclear protein in the context of late apoptotic cells.

Materials and methods

Mice

Mice heterozygous for the wild-type hLa Tg, including its natural promoter, have been described [21] and were maintained by back-crossing to A/J mice (Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME, USA) in specific pathogen-free conditions. Line 3 hLa Tg mice express nuclear hLa ubiquitously at levels similar to the endogenous mouse La (mLa) protein [21]. The hLa Tg mice used in this study were back-crossed to A/J ≥ 12 generations, and Tg mice were identified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis of tail DNA using hLa specific primers hLaEx3.for (5′-CTTCAATTTGCCACGG-3′) and hLaEx4.rev (5′-GGGTTTGCTTGGAGAC-3′). To create hLa Tg mice on the (A/J × BALB/c)F1 background, A/J mice heterozygous for the hLa Tg were crossed with BALB/c mice (Jackson Laboratories) and genotyped for the hLa Tg as described above. All studies were approved by the Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Preparation of apoptotic murine thymocytes and 3T3 fibroblasts

Thymocyte single cell suspensions were prepared by sieving thymuses through sterile 40-mesh screens in T cell culture medium (cTCM); Dulbecco's minimum essential medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) or mouse serum (which gave indistinguishable results for the phenotypes reported herein), 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 µg/ml streptomycin (Fisher, Hampton, NH, USA), 2 mM glutamine (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA), 2 mM Na pyruvate (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD, USA), 0·1 mM non-essential amino acids solution (Life Technologies) and 50 µM 2-mercaptoethanol). Cells were washed twice in tissue culture medium (cTCM), exposed to 600 rad γ-irradiation, then cultured at 2 × 107 cells/ml in cTCM in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 for varied periods of time, as described in the text.

Murine BALB/c-derived 3T3 fibroblasts (BALB/3T3 clone A31, American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA, USA) transfected with the hLa gene (hLa-3T3) or a control plasmid (c-3T3) have been described [22] and were cultured at 37°C in DMEM supplemented with 10% FCS, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 µg/ml streptomycin, 2 mM glutamine, 2 mM Na pyruvate and 200 µg/ml neomycin (Sigma). For induction of apoptosis, cells were harvested from tissue culture flasks, washed, resuspended in unsupplemented DMEM, exposed to 600 rad γ-irradiation, then cultured at 2 × 107 cells/ml in unsupplemented DMEM for 16 h at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2.

Confocal microscopy

Immunofluorescence microscopy was performed on hLa-Tg apoptotic thymocytes transferred to microscope slides by cytospin and fixed immediately in ice-cold ethylene glycol tetraacetic acid (EGTA)-saturated methanol for 1 h or overnight. Slides were incubated with SW5-specific anti-hLa monoclonal antibody (mAb) [23] for 60 min at room temperature, and then washed extensively with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (Jackson Immunoresearch, West Grove, PA, USA; used at 1 : 200) was applied for 60 min at room temperature. The slides were washed with PBS and coverslips mounted over PBS buffered glycerine. Imaging was performed using a confocal microscope equipped with an argon–krypton laser (LSM-MicroSystem, Zeiss, Germany).

Flow cytometry

AnnexinV-FITC/propidium iodide (PI) double staining was performed on apoptotic cells using the annexinV-FITC apoptosis detection kit (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. For analytical fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS), Fc receptors on DC and B cells were blocked with a solution of 20% FCS, 10% mouse serum and 5 µg/ml rat anti-mouse CD16/CD32/FcγIII/II receptor (Mouse Fc Block, clone 2·4G2) in 1× PBS on ice for 30 min to prevent non-specific mAb binding. DC were then incubated with phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated anti-CD11c (clone HL3), and B cells were incubated with allophycocyanin-conjugated anti-CD19 (clone 1D3) mAb for 30 min at 4°C. All antibodies for flow cytometry were from BD Pharmingen (San Diego, CA, USA). At least 10 000 events were collected on a FACSCalibur™ instrument and live-gated cells analysed with CELLQuest™ software (Becton Dickinson FACScan, Mountain View, CA, USA).

Immunization protocol

Apoptotic thymocytes from hLa Tg or non-Tg A/J mice were washed in 100× volume (compared to cell pellet) PBS (Invitrogen Gibco, Carlsbad, PA, USA) then resuspended in PBS at a concentration based on the percentage of apoptotic cells as assessed by flow cytometry at 16 h. Six- to 8-week-old female A/J mice were immunized subcutaneously (s.c.) with a known number of annexinV+ cells per mouse in 0·2 ml PBS on days specified in the text. Apoptotic hLa-3T3 or control-3T3 cells were prepared similarly, and 6-week-old female hLa-Tg and non-Tg mice were immunized s.c. with an average of 2 × 107 annexinV+ cells per mouse in 0·2 ml PBS for a total of three immunizations on days 0, 10 and 24. In some experiments, mice were immunized with PBS-washed, freshly isolated thymocytes or a mixture of freshly isolated thymocytes and late apoptotic cells.

Antigens and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs)

Recombinant soluble hLa used for in vitro detection of antibodies was produced in bacteria as an in-frame six-histidine fusion protein (6xhis-hLa [24]) from the pQE vector (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) and was purified by Ni2+ affinity chromatography. Alternatively, recombinant soluble hLa was prepared in bacteria as a fusion protein to GST-hLa [24] using the pGEX-2T expression vector (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ, USA) and was purified by glutathione-Sepharose 4 B beads (Amersham Pharmacia). Recombinant mLa (6xhis-mLa [25]) and dihydrofolate reductase (6xhis-DHFR) control protein were produced similarly. Endotoxin was removed from proteins used for T cell assays by passage over Detoxi-Gel™ polymyxin B columns (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL, USA), and lipopolysaccharide (LPS) removal was confirmed by the limulus amoebocyte lysate test according to the microplate method of the manufacturer (BioWhittaker, Inc., Walkersville, MD, USA) and by observing lack of T cell mitogenic activity for each preparation. Linear synthetic peptides were prepared by the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center molecular biology resource facility, using standard 9-fluorenylmethyloxycarbonyl (Fmoc) chemistry, were purified to > 95% by high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and were verified by amino acid analysis and mass spectrometry. ELISA assays for IgG antibodies to recombinant proteins were conducted as described previously [26].

T cell hybridomas

KD9B9 (hLa288–302-specific) and KD3C5 (hLa 61–84-specific) T cell hybridomas with specificity for the H-2a-restricted immunodominant T cell epitopes of hLa [24] were generated according to the method of White [27]. The fusion partner was BW1547α-β- [27] and was provided generously by Drs John Kappler and Philippa Marrack. Primed T cells were taken from the draining LN of A/J mice that had been immunized s.c. 7 days earlier with 100 µg 6xhis-hLa emulsified 1 : 1 in H37Ra CFA (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, MI, USA) and were cultured in the presence of synthetic hLa 288–302 (KD9B9) or hLa 61–84 (KD3C5) peptide during the initial 4-day culture period to select for the desired specificities.

Purification of DC and B cells

The DC isolation procedure was performed essentially as described [28, 29]. Briefly, LN from 25 to 45 mice were cut into small fragments and digested at 37°C for 45 min in 10 ml of RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% FCS, 5 mM ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA) and 15 mM HEPES, containing 1 mg/ml collagenase D (Sigma) and 50 µg/ml Dnase I (Sigma). Collagenase D-released cells were resuspended in RPMI-1640 and DC purified by positive selection using magnetic affinity cell sorting (MACS) CD11c (N418) MicroBeads (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA, USA). In some cases, B cells were isolated from the DC-negative fraction using a similar procedure with MACS CD19 MicroBeads. In other experiments B cells were isolated without DC purification, and in those cases collagen digestion was omitted.

Cellular assays

T cell proliferation assays were performed as described [26], except that cells were harvested onto glass-fibre filters (PhD Cell Harvester, Cambridge Technology, Inc., Cambridge, MA, USA) and counted by liquid scintillation.

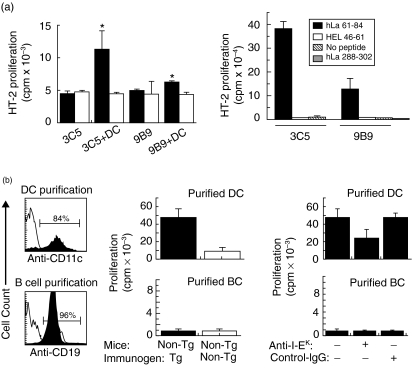

Presentation of specific peptides by DC and B cells from apoptotic cell-primed mice was assessed using KD3C5 (hLa 61–84-specific) and KD9B9 (hLa 288–302-specific) T cell hybridomas. Positively selected DC or B cells were isolated from draining LN 36–48 h after mice had been immunized s.c. in the tail base and one hind footpad with 3 × 107 annexinV+ cells from hLa Tg or non-Tg mice. DC or B cells were then cultured in triplicate with appropriate hLa-specific T cell hybridomas (8 × 104 cells/well) in cTCM in 96-well culture plates (Corning Costar Corp., Acton, MA, USA). After 24 h of culture, 80 µl aliquots of supernatants were taken, frozen overnight at −86°C then transferred to microculture wells containing 104 HT-2 cells per well. After an additional 24 h incubation, the presence of interleukin (IL)-4 and/or IL-2 was assessed by [3H]thymidine incorporation (1 µCi/well) during the last 16 h of culture. Some hybridoma cells were incubated with 3 × 105 irradiated A/J splenocytes and 10 µM purified hLa 61–84 or 288–302 peptides as positive controls. Some cultures, as indicated in the text, contained 25 µg/ml anti-I-Ek (clone 14–4−4S) or isotype control mAb (clone G155–178), both from BD Pharmingen.

Results

Late apoptotic cells bearing heterologous La/SS-B nuclear antigen are immunogenic for the production of anti-La-specific antibodies

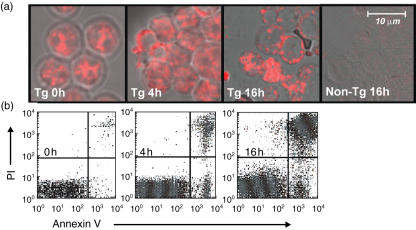

It is unclear whether cells in the late stages of apoptosis are immunogenic for the production of ANA directed to common targets in human SLE in non-autoimmune-prone mice. The ability of inbred mice to produce T cell-dependent antibody responses to purified antigens is determined in large part by major histocompatibility complex (MHC) haplotype, and the ability to respond to ‘self’-antigens is determined additionally by the degree of existing immune tolerance. In this study, we have utilized a strain of mouse (A/J) known to produce strong T and B cell responses to the hLa/SS-B antigen (hLa) in the presence of adjuvants [24], to assess directly the immunogenicity of heterologous hLa expressed by late apoptotic cells in vivo in the absence of foreign adjuvants. Late apoptotic thymocytes for immunization of A/J mice were prepared from Line 3 hLa transgenic (Tg) A/J mice [21] by exposure of the cells to gamma irradiation followed by overnight culture. Immunofluorescence confocal microscopy with an hLa-specific mAb revealed that hLa protein in these thymocytes redistributed to surface blebs within 16 h of irradiation (Fig. 1a). By that time 66 ± 15% of cells were routinely annexinV+, while 53 ± 15% of these were in late stages of apoptosis (data from 12 experiments) as measured by PI staining (Fig. 1b shows a typical result). At the 4-h time-point post-irradiation, hLa was observed to translocate from the nucleus to the cytoplasm in a subset of cells (Fig. 1a). As shown in a typical experiment, at 4 h post-irradiation, this corresponded to a detection of cell surface annexinV staining in 14% of the population (Fig. 1b). A significant fraction of annexinV+ cells were PI+ at every time-point tested, precluding an analysis of the immunogenicity of ‘early’ annexinV+PI– apoptotic cells.

Fig. 1.

Redistribution of human La (hLa) antigen in hLa transgenic (Tg) thymocytes. (a) Confocal images showing morphological changes of hLa Tg thymocytes that were stained at various time-points following γ-irradiation (600 rad) with the SW5 anti-hLa-specific monoclonal antibody (mAb). No staining of control non-Tg thymocytes by SW5 mAb was observed. (b) Fluorescence activated cell sorter (FACS) dot-plots showing annexinV-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) and propidium iodide (PI) staining of portions of the irradiated cells from (a).

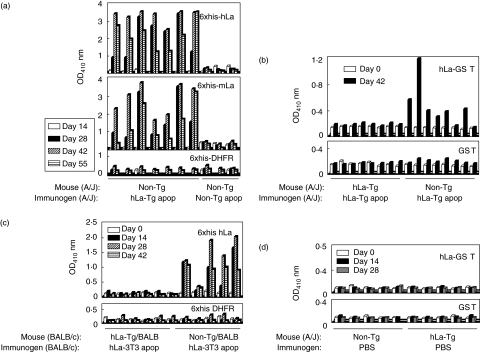

To determine whether heterologous La nuclear antigen is immunogenic in the context of late apoptotic cells in a non-lupus prone strain of mouse, 6–8-week-old non-Tg A/J mice were given s.c. injections of hLa Tg late (16 h post-irradiation) apoptotic cells (4 × 107 annexinV+ cells per injection) on days 0, 10 and 24, followed by intraperitoneal injections on days 38 and 52. Serial serum samples were assayed by ELISA for binding to recombinant 6xhis-hLa, -mLa and control -DHFR proteins. Figure 2a shows one representative result of three experiments in which seven of seven normal, non-Tg A/J mice immunized with hLa Tg apoptotic cells developed IgG anti-hLa and anti-mLa antibodies beginning at day 28 post-immunization. In contrast, mice receiving an identical immunization schedule in parallel with late apoptotic cells taken from totally syngeneic mice (4 × 107 annexinV+ cells per injection) failed to produce antibodies to human or mouse La (Fig. 2a).

Fig. 2.

Anti-La/SS-B responses elicited by human La (hLa) transgenic (Tg) or non-Tg late apoptotic thymocytes. (a) Detection of IgG antibodies binding to six-histidine fusion protein (6xhis-hLa), -mouse La (-mLa) and control -dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) proteins by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) in immune (days 14, 28, 42, 55) sera (1 : 50 dilutions) from non-Tg A/J mice immunized with hLa Tg or non-Tg late apoptotic thymocytes. (b) Detection of IgG antibodies binding to recombinant hLa-GST and control GST proteins by ELISA in preimmune (day 0) and immune (day 42) sera (1 : 100 dilutions) of hLa Tg and non-Tg mice immunized with hLa Tg late apoptotic thymocytes. (c) Detection of IgG antibodies binding to 6xhis-hLa and control -DHFR proteins by ELISA in preimmune (day 0) and immune (days 14, 28, 42) sera (1 : 100 dilutions) of (BALB/c × A/J)F1 mice immunized with BALB/c-derived 3T3 cells transfected with a plasmid containing the hLa gene (hLa-3T3) or a control plasmid (c-3T3). (d) Lack of detection of anti-La antibodies in the sera of control mice serially immunized with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) buffer alone.

We have shown previously that T helper cells of mice Tg for hLa nuclear antigen are tolerant to hLa [21], while little evidence was found for tolerance to this antigen in the B cell compartment [21, 30]. To determine if immunization with late apoptotic cells can break existing tolerance to hLa in this well-characterized model, hLa Tg mice were given s.c. immunizations (3 × 107 annexinV+ cells per injection) of hLa Tg thymocytes in late stages of apoptosis on days 0, 10 and 24. As shown in one representative experiment of three in Fig. 2b, none of eight hLa Tg mice immunized with hLa Tg apoptotic cells produced IgG anti-hLa antibodies, while six of eight non-Tg mice receiving the same immunogen produced such antibodies. Mice receiving injections of PBS alone failed to produce any detectable anti-La antibodies (Fig. 2d).

To validate these observations further using another cell type as immunogen, groups of hLa Tg or non-Tg mice on the (BALB/c × A/J)F1 background were immunized similarly with apoptotic BALB/c-derived 3T3 fibroblasts that had been transfected with the hLa gene (hLa-3T3) or a control vector (c-3T3) on days 0, 10 and 24. Again, only mice immunized with apoptotic cells harbouring heterologous La nuclear antigen produced anti-La antibodies (Fig. 2c).

Eight of 11 anti-La producing, non-Tg mice that had been immunized with hLa-expressing thymocytes also produced IgG antibodies reactive with purified bovine (Fig. 3) and recombinant mouse Ro (not shown) proteins, while none of seven anti-La negative immunized mice produced such antibodies. The development of anti-Ro antibodies was thus associated with the development of anti-La antibodies (P = 0·004; Fisher's exact test).

Fig. 3.

Anti-Ro antibodies occur only in the sera of mice that make antibodies to La. Non-transgenic (Tg) mice were immunized with human La (hLa) Tg thymocytes (hLa Tg), hLa transfected 3T3 cells (hLa-3T3), completely syngeneic apoptotic thymocytes (non-Tg) or 3T3 cells transfected with control plasmid alone (c-3T3). Individual serial serum samples were screened for IgG antibodies to purified bovine La (top panel) or 60 kDa Ro (bottom panel) by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Data from individual mice are presented in the same order for each panel. Data from two independent experiments are shown.

In summary, late apoptotic cells harbouring a nuclear antigen containing known heterologous T cell epitopes and probable heterologous B cell epitopes of hLa are immunogenic for the production of IgG anti-hLa antibodies in the absence of added adjuvants. Given a single murine MHC haplotype (H-2a; I-Ak and I-Ek), existing tolerance to the La antigen was maintained in the case of immunization with completely syngeneic late apoptotic cells.

Late apoptotic cells and phenotypically healthy thymocytes expressing heterologous La antigen are immunogenic but late apoptotic cells do not exert an adjuvant effect for healthy cells

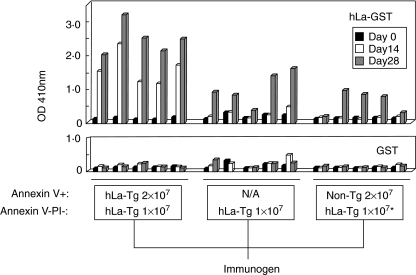

Late apoptotic cell preparations (16 h post-irradiation) were inevitably contaminated with phenotypically healthy cells that did not bind annexinV and did not admit and bind PI (34 ± 15% annexinV–PI–; data from 12 experiments). In order to determine whether such initially healthy cells participated in or were responsible for the observed induction of anti-La antibodies in non-Tg mice immunized with late apoptotic cell preparations taken from hLa Tg mice, groups of A/J mice were immunized s.c. (day 0) and boosted (days 10 and 24) with 1 × 107 freshly isolated, hLa Tg thymocytes per injection (92 ± 7% annexinV–PI– for the three injections) or with 3 × 107‘late apoptotic’ hLa Tg thymocytes (71 ± 2% annexinV+ 29 ± 2% annexinV–PI– for the three injections), such that the dose of cells with a non-apoptotic phenotype (annexinV–PI–) was equivalent in both cases. Analysis of serial serum samples showed that thymocytes with an initially non-apoptotic phenotype induced anti-hLa antibodies; however, the antibody response was appreciably delayed compared to that of mice receiving injections of late apoptotic cell preparations that contained an equivalent number of phenotypically healthy cells (Fig. 4, left and centre panels). Thus, in one of two experiments giving similar results, none of five mice receiving injections of only healthy cells produced detectable IgG anti-hLa antibodies at day 14 of the immunization protocol, while five of five mice receiving the same number of healthy cells plus phenotypically late apoptotic cells produced such antibodies at the same time-point. At day 28 both groups of mice produced detectable anti-hLa antibodies, but anti-hLa reactivity was enhanced significantly in mice injected with the late apoptotic cell preparation (P = 0·0079; Wilcoxon's rank sum test). Thus, the early, enhanced response induced by hLa Tg late apoptotic cells cannot be ascribed to the immunogenicity of phenotypically healthy cells that were present in the late apoptotic cell preparations.

Fig. 4.

Late apoptotic cells expressing heterologous La/SS-B are immunogenic. A/J mice (five mice per group) were immunized on days 0, 10 and 24, with cell preparations containing numbers of the cell phenotypes listed below each panel and enclosed by the boxes, and serial serum samples were tested for IgG antibody reactivity to the hLa-GST antigen (top panel) or the control GST protein (bottom panel). N/A = none added; *injections in this group also contained 1 × 107 non-transgenic (Tg) annexinV–propidium iodide (PI)– cells.

In order to determine whether the enhanced responses seen in the case of late apoptotic cell immunization were caused simply by an adjuvant effect of late apoptotic cells, or whether human La antigen expressed by the late apoptotic cells themselves was responsible, groups of mice were immunized with initially healthy, freshly isolated hLa Tg thymocytes (1 × 107 cells per injection; 92 ± 7% annexinV–PI– for the three injections) mixed with non-Tg thymocytes that were in the late stages of apoptosis (3 × 107 cells per injection; 69 ± 3% annexinV+ 31 ± 3% annexinV–PI– for the three injections), and their serological responses to the hLa antigen were followed. The addition of non-Tg cells in late stages of apoptosis to the healthy cell immunogen did not reduce or increase the time to the first detectable anti-La antibody response or the magnitude (P = 0·222; Wilcoxon's rank sum test) of serological reactivity to La at day 28 (Fig. 4, right and centre panels), indicating that late apoptotic cells did not exert an adjuvant effect for the response induced by the healthy cell preparation.

LN DC present immunodominant T cell epitopes of heterologous La/SS-B following late apoptotic cell immunization

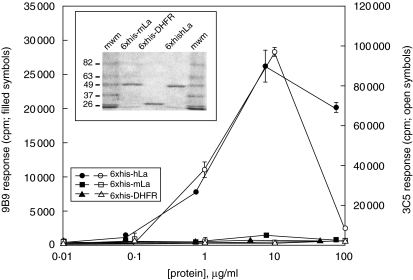

To facilitate investigation of the type(s) of APCs that might initiate autoantibody generation following immunization of mice with syngeneic late apoptotic cells containing heterologous epitopes of La, human-La specific T cell hybridomas were generated. LN T cells of 6xhis-hLa-immunized A/J mice were fused to the BW5147α-β- fusion partner [27], and two independent hybridomas (KD9B9 and KD3C5) that were studied in detail were found to be hLa-specific (Fig. 5). Similar studies using synthetic peptides of the known H-2a-restricted T cell epitopes of hLa showed that 9B9 is specific for the hLa288–302 immunodominant epitope, while KD3C5 is I-Ek-restricted (not shown) and specific for the hLa61–84 immunodominant T cell epitope (data not shown and Fig. 6a, right panel).

Fig. 5.

Human La-specific T cell hybridomas KD9B9 and KD3C5. T cell hybridomas generated by immortalization of six-histidine fusion protein (6xhis-hLa)-primed lymph node (LN) T cells responded to the 6xhis-hLa antigen but not the 6xhis-mLa antigen or an irrelevant 6xhis-linked control protein. Proliferation of the interleukin (IL-4) and/or IL-2-dependent HT-2 cell line to T cell hybridoma supernatants is reported. Inset: Coomassie-stained sodium dodecyl sulphate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis showing the purity and expected mobility of the antigens used in this assay (2 µg protein per lane).

Fig. 6.

Presentation of immunodominant T cell epitopes of human La (hLa) by lymph node (LN) dendritic cells (DC) from mice injected with hLa transgenic (Tg) late apoptotic thymocytes. (a) Positively selected CD11c + LN DC taken from mice immunized once with hLa Tg late apoptotic thymocytes (filled bars, left panel) or non-Tg late apoptotic thymocytes (open bars, left panel) were assayed for the ability to present immunodominant H-2a-restricted T cell epitopes of the hLa antigen to hLa-specific T cell hybridomas. Peptide specificity of KD3C5 (3C5) for hLa 61–84 and KD9B9 (9B9) for hLa 288–302 was verified by culture of the hybridomas with the indicated synthetic peptides and irradiated syngeneic splenocytes from unimmunized A/J mice (right panel). Responses were assessed by measuring tritiated thymidine uptake of the HT-2 cell line when incubated with cell culture supernatants from T cell hybridomas cultured alone or with the indicated LN DC. *Indicates significant differences in responses compared to T cells cultured without DC or with DC exposed to late apoptotic cells in vivo (P < 0·05, Student's t-test). (b) CD11c+ DC and CD19+ B cells were purified from the draining LN of mice injected once with hLa Tg or non-Tg late apoptotic thymocytes, then assayed for the ability to present the hLa 61–84 immunodominant T cell epitope to the KD3C5 T cell hybridoma. Fluorescence activated cell sorter (FACS) histograms show anti-CD11c or -CD19 staining of LN cells before purification (open plots) or after purification (filled plots). Presentation of the immunodominant I-Ek-restricted T cell epitope recognized by the KD3C5 hybridoma by DC but not by B cells was detected (centre panel). Presentation of this epitope was inhibited in the presence of a blocking anti-I-Ek monoclonal antibody (mAb) but not by an isotype control mAb (right panel).

Induction of IgG anti-La antibodies after immunization of non-Tg mice with hLa-expressing late apoptotic cells but not non-Tg apoptotic cells implies the participation of hLa-specific helper T cells (Th) in the initiation of this response. In order to determine whether the known H-2a-restricted T cell epitopes of the hLa protein [24] were presented by LN APC after apoptotic cell immunization, DC isolated from the draining LN of mice injected once with hLa-expressing apoptotic cells in PBS in the absence of adjuvant were assayed for the capacity to stimulate T cell hybridomas specific for the two known immunodominant T cell epitopes of hLa. Because T cell hybridoma stimulation does not require co-stimulation, positively selected CD11c+ cells were used to enhance the purity of the DC population. Figure 6a shows that T cell hybridomas recognizing both the immunodominant 61–84 (KD3C5) and the immunodominant 288–302 (KD9B9) epitopes of the hLa antigen were stimulated to secrete IL-4 and/or IL-2, as measured by the proliferation of HT-2 cells, following incubation with CD11c+ DC taken from mice injected with hLa expressing late apoptotic cells. The amounts of IL-4 and/or IL-2 secreted in these cultures were significantly greater than the amounts secreted by hybridomas cultured with DC isolated similarly from mice that had been injected with late apoptotic cells taken from non-Tg mice.

To confirm these results and to examine further the possibility that other types of APC might be involved in the initiation of anti-La specific ANA in this model, groups of non-Tg A/J mice were injected s.c. with either hLa Tg or non-Tg apoptotic cells in PBS, and 36 h later draining LN were removed for APC purification. CD11c+ DC, CD19+ B cells and CD11b+ macrophages were isolated successively by micromagnetic bead positive selection. Negligible numbers of CD11b+ cells were recovered by this procedure from CD11c -depleted cells and therefore were not studied further. Flow cytometric analysis of aliquots of the thus isolated cells confirmed purities of 80–84% CD11c+ and 96–98% CD19+ cells for DC and B cell populations, respectively (Fig. 6b, left panel). When tested for presentation of the hLa61–84 immunodominant T cell epitope, DC isolated from mice injected with hLa-expressing apoptotic cells again presented this epitope (Fig. 6b, centre panel). In contrast, purified LN B cells taken from mice injected once with hLa-expressing apoptotic cells did not (Fig. 6b). Inclusion of blocking mAb directed to I-Ek in the cultures reduced stimulation of the 61–84-specific T cell hybridoma, while isotype control mAb had no effect (Fig. 6b, right panel). These data indicate that LN CD11c+ DC presented immunodominant T cell epitopes of hLa in association with MHC class II following in vivo exposure to late apoptotic cells expressing the hLa antigen.

Discussion

Mice with defects in the clearance of apoptotic cells develop ANA [14, 15, 31]; however, the specific mechanisms leading to ANA production when the immune system is presented with an excess of apoptotic cells are still understood incompletely. It is suspected that both the generation of neo-epitopes and genetic predisposition are likely to contribute to these responses. The studies reported herein have explored the inherent immunogenicity of cells in the late stages of apoptosis for the induction of antibodies to the La/SS-B antigen, in a non-autoimmune mouse strain. The well-characterized immune response to this antigen in A/J mice has been exploited to provide direct experimental support for the hypothesis [6, 19, 32] that apoptotic cells containing modified antigens of nuclear origin can initiate an immune response in the absence of foreign adjuvants. In these studies, defective clearance of apoptotic cells was mimicked by s.c. administration of an excess of cells in late stages of apoptosis. Under these conditions, mice known to express the appropriate MHC restriction elements for an immune response to the hLa antigen produced anti-hLa antibodies readily when the late apoptotic cells expressed hLa-specific heterologous determinants that mimic apoptosis-induced neo-epitopes. Thus, despite observations that late apoptotic cells can inhibit DC maturation in vitro [12, 13], late apoptotic cells do not prevent immunogenicity in vivo.

Antibodies to mLa (Fig. 2) and Ro (Figure 3) antigens were observed in the sera of mice that produced antibodies to hLa but not in the sera of immunized mice that did not produce antibodies to hLa. Given the fixed time-points of serum collection in these studies, the development of IgG anti-Ro antibodies could not be ascribed to epitope spreading, nor could epitope spreading be ruled out as mechanism for their presence.

Preparations of phenotypically healthy hLa Tg thymocytes induced anti-hLa antibodies in non-Tg mice. However, the reduced and delayed responses observed after immunization of mice with the same number of healthy cells that contaminated late apoptotic cell preparations, combined with the lack of an observable adjuvant effect of non-Tg late apoptotic cell preparations for hLa-expressing phenotypically healthy cells, indicates that these apparently healthy cells contributed to but were not solely responsible for the anti-hLa humoral responses observed. This demonstrates clearly that the apoptotic cells themselves were immunogenic, which is the central theme of the present line of investigation. The extent that phenotypically early or late apoptotic cells induced this response could not be determined definitively, because irradiation resulted in significant fractions of late apoptotic cells at every time-point tested. The relative immunogenicity of phenotypically healthy versus late apoptotic cells was not compared directly in the present study, and the potential significance of healthy cell immunogenicity is likely to depend upon the mechanism(s) responsible. We speculate that priming of hLa-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL) in non-Tg mice may have resulted in the killing of hLa-expressing healthy cells upon subsequent injections. Other possibilities that have not been excluded include immunogenicity of the small numbers of annexinV+PI– early apoptotic cells that contaminated the healthy cell preparations or immunogenicity of cells that apoptosed in situ after injection. Regardless of these possibilities, the data presented in Fig. 4 demonstrate clearly immunogenicity of apoptotic cells in vivo.

Could non-physiological over-expression of hLa antigen in hLa Tg mice be responsible for the humoral anti-La responses observed in non-Tg mice immunized with hLa Tg apoptotic cells in this study? The expression levels of hLa antigen in hLa Tg mice have been investigated carefully and reported previously [21]. Although a completely precise, direct comparison of human and mouse La protein levels is not possible due to the lack of an available hLa-specific mAb with identical affinity for both the human and mouse La antigens, simultaneous detection of human and mouse La in serial dilutions of spleen cell extracts by quantitiative immunoblot with the 3B9 anti-La mAb that recognizes both human and mouse La antigens failed to reveal gross differences in the expression levels of human and mouse La in Line 3 hLa Tg mice [21]. In that same study, the expression of Tg hLa appeared weaker in the thymus of hLa Tg mice compared to other tissues [21]. These data suggest that Line 3 hLa Tg thymocytes, used as an apoptotic cell source in the current study, are unlikely to over-express the hLa antigen. This conclusion is supported further by the observation that copy numbers of hLa and mLa mRNA in tissues of Line 3 hLa Tg A/J mice and copy numbers of mLa mRNA in non-Tg littermates are not different from each other, as revealed by quantitative PCR (M. Bachmann et al., data not shown).

Could the increased expression of total La antigen (hLa plus mLa) in hLa Tg apoptotic cells account for the observed immunogenicity of La in the present studies independently of heterologous epitopes? An exhaustive mapping study revealed a total of 10 H-2a-restricted hLa T cell epitopes in A/J mice primed with hLa antigen in strong adjuvant [24]. Seven of these 10 epitopes were heterologous, while only three of these epitopes were identical in sequence to the mouse La antigen (autologous). Two of the six heterologous epitopes (hLa 288–302 and hLa 61–84) dominated the response, with high stimulation indexes in all (eight of eight) or nearly all (six of eight) of the independent experiments conducted, while all remaining epitopes (five heterologous and three autologous) were weak and induced responses detectable above background in only a minority of experiments. Of the three ‘autologous’ epitopes, only one was capable of inducing anti-La antibodies in mice immunized with peptide in strong adjuvant. In contrast to this, four of four peptides containing heterologous epitopes have been shown to induce T helper cells capable of inducing anti-La antibodies in A/J mice ([21] and data not shown). In the case of immunization of non-Tg mice with hLa Tg apoptotic cells as described in the present study, there is likely to be an approximate twofold increase in the processing of the three subdominant autologous epitopes relative to natural cells. We conclude that the sum of the response to the seven heterologous hLa epitopes that includes two immunodominant ones would eclipse any response induced by a twofold enhancement of the processing of a single subdominant mLa epitope that is capable of inducing a humoral response. This view is supported further by the observed presentation of the two immunodominant hLa epitopes by LN DC of mice receiving a single apoptotic cell injection in the absence of adjuvant.

Although hLa containing known heterologous T cell epitopes was immunogenic for non-Tg mice when expressed by cells in late apoptosis, existing tolerance to the hLa antigen was maintained in immunized hLa Tg mice despite repeated challenge with completely syngeneic late apoptotic cells. Similarly, tolerance to mLa was maintained in non-Tg A/J mice receiving completely syngeneic cell injections. These results are consistent with our previous studies documenting tolerance in the T helper cell compartment in hLa Tg mice [21]. Tolerance to La in the CD8+ T cell compartment could contribute additionally to the lack of immunogenicity of completely syngeneic healthy cells in these experiments, thus potentially preventing generation of apoptotic cells in vivo due to possible hLa-specific CTL priming and subsequent killing of injected hLa-Tg cells. The lack of detectable antibodies to La after syngeneic apoptotic cell immunization is not inconsistent with a previously published report of ANA generated in mice following administration of four weekly intravenous injections of syngeneic thymocytes (4 h post-irradiation) to several normal strains of inbred mice [33]. Although sera of the immunized mice produced an ANA pattern by indirect immunofluorescence in that study, no specific protein antigens to which the induced antibodies bound could be identified by immunoblot using whole cell extracts, nuclear extracts or specific recombinant proteins. We argue that ANA production in apoptotic cell-immunized non-autoimmune-prone mice is expected, requires the generation of neo-epitopes during apoptosis, and that the particular specificities generated depend upon the genetic makeup of the host, especially the MHC haplotype.

As discussed previously, two immunodominant and several subdominant H-2a-restricted T cell epitopes of hLa have been described in A/J mice [24], and the core immunodominant determinants differ from the homologous mLa sequences by single amino acid residues ([24] and data not shown). The presentation of these immunodominant T cell epitopes by LN DC following immunization of mice with hLa expressing late apoptotic cells suggests that DC were likely to have participated in the initiation of the observed anti-La humoral responses. Although determinants of hLa were detected only on DC but not B cells after a single apoptotic cell injection, other APC might play important roles in amplifying the response at later stages, particularly after B cell activation or macrophage accumulation. Identification of critical components of late apoptotic cells that might transform DC into effective APC remains a critical and outstanding question that is currently under investigation. Although in vitro studies have failed to show maturation of DC by syngeneic cells in the late stages of apoptosis [10, 11] this question warrants further in vivo study, where effects such as cytokine secretion by stromal cell types could be important [34].

In conclusion, this study has taken advantage of a relatively well-understood antigenic system to show that apoptotic cells are not inherently non-immunogenic, as has been implied by some in vitro studies. Moreover, the development of IgG antibodies to a clinically relevant extractable nuclear antigen following late apoptotic cell immunization of non-autoimmune prone mice required the presence of neo-epitope-mimicking heterologous epitopes. This study lends experimental support to the concept that apoptosis-related modifications to nuclear antigens, resulting in the creation of neo-T cell epitopes, can contribute to ANA development under conditions of apoptotic cell excess and/or defective clearance mechanisms.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health grants R01 AI48097, K02 AI051647 and P50 AR048940-01. The authors thank Ms Kathy Bryant for expert clerical assistance, and the staffs of the OMRF Imaging Core Facility, Flow Cytometry Core Facility, Laboratory Animal Resources Center and Graphics Resources Center. The authors are grateful to Drs Morris Reichlin, Joel Guthridge and Richard Sonthemier for providing helpful comments.

References

- 1.Tan EM. Autoantibodies to nuclear antigens (ANA): their immunobiology and medicine. Adv Immunol. 1982;33:167–240. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60836-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harley JB, Alexander EL, Bias WB, et al. Anti-Ro (SS-A) and anti-La (SS-B) in patients with Sjogren's syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 1986;29:196–206. doi: 10.1002/art.1780290207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buyon JP, Clancy RM. Autoantibody-associated congenital heart block: TGFbeta and the road to scar. Autoimmun Rev. 2005;4:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2004.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reichlin M. Systemic lupus erythematosus and pregnancy. J Reprod Med. 1998;43:355–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arbuckle MR, McClain MT, Rubertone MV, et al. Development of autoantibodies before the clinical onset of systemic lupus erythematosus. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1526–33. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Casciola-Rosen LA, Anhalt G, Rosen A. Autoantigens targeted in systemic lupus erythematosus are clustered in two populations of surface structures on apoptotic keratinocytes. J Exp Med. 1994;179:1317–30. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.4.1317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Savill J. Recognition and phagocytosis of cells undergoing apoptosis. Br Med Bull. 1997;53:491–508. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a011626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Voll RE, Herrmann M, Roth EA, Stach C, Kalden JR, Girkontaite I. Immunosuppressive effects of apoptotic cells. Nature. 1997;390:350–1. doi: 10.1038/37022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fadok VA, Bratton DL, Konowal A, Freed PW, Westcott JY, Henson PM. Macrophages that have ingested apoptotic cells in vitro inhibit proinflammatory cytokine production through autocrine/paracrine mechanisms involving TGF-beta, PGE2, and PAF. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:890–8. doi: 10.1172/JCI1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gallucci S, Lolkema M, Matzinger P. Natural adjuvants: endogenous activators of dendritic cells. Nat Med. 1999;5:1249–55. doi: 10.1038/15200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sauter B, Albert ML, Francisco L, Larsson M, Somersan S, Bhardwaj N. Consequences of cell death: exposure to necrotic tumor cells, but not primary tissue cells or apoptotic cells, induces the maturation of immunostimulatory dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2000;191:423–34. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.3.423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stuart LM, Lucas M, Simpson C, Lamb J, Savill J, Lacy-Hulbert A. Inhibitory effects of apoptotic cell ingestion upon endotoxin-driven myeloid dendritic cell maturation. J Immunol. 2002;168:1627–35. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.4.1627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clayton AR, Prue RL, Harper L, Drayson MT, Savage CO. Dendritic cell uptake of human apoptotic and necrotic neutrophils inhibits CD40, CD80, and CD86 expression and reduces allogeneic T cell responses: relevance to systemic vasculitis. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:2362–74. doi: 10.1002/art.11130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Botto M, Dell'Agnola C, Bygrave AE, et al. Homozygous C1q deficiency causes glomerulonephritis associated with multiple apoptotic bodies. Nat Genet. 1998;19:56–9. doi: 10.1038/ng0598-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mitchell DA, Pickering MC, Warren J, et al. C1q deficiency and autoimmunity: the effects of genetic background on disease expression. J Immunol. 2002;168:2538–43. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.5.2538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Herrmann M, Voll RE, Zoller OM, Hagenhofer M, Ponner BB, Kalden JR. Impaired phagocytosis of apoptotic cell material by monocyte-derived macrophages from patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41:1241–50. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199807)41:7<1241::AID-ART15>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Herrmann M, Zoller OM, Hagenhofer M, Voll R, Kalden JR. What triggers anti-dsDNA antibodies? Mol Biol Rep. 1996;23:265–7. doi: 10.1007/BF00351179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosen A, Casciola-Rosen L, Ahearn J. Novel packages of viral and self-antigens are generated during apoptosis. J Exp Med. 1995;181:1557–61. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.4.1557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Casciola-Rosen L, Andrade F, Ulanet D, Wong WB, Rosen A. Cleavage by granzyme B is strongly predictive of autoantigen status: implications for initiation of autoimmunity. J Exp Med. 1999;190:815–26. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.6.815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Utz PJ, Anderson P. Posttranslational protein modifications, apoptosis, and the bypass of tolerance to autoantigens. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41:1152–60. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199807)41:7<1152::AID-ART3>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Keech CL, Farris AD, Beroukas D, Gordon TP, McCluskey J. Cognate T cell help is sufficient to trigger anti-nuclear autoantibodies in naive mice. J Immunol. 2001;166:5826–34. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.9.5826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bachmann M, Deister H, Pautz A, et al. The human autoantigen La/SS-B accelerates herpes simplex virus type 1 replication in transfected mouse 3T3 cells. Clin Exp Immunol. 1998;112:482–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1998.00605.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith PR, Williams DG, Venables PJW, Maini RN. Monoclonal antibodies to the Sjögren's syndrome associated antigen SS-B (La) J Immunol Meth. 1985;77:63–76. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(85)90184-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reynolds P, Gordon TP, Purcell AW, Jackson DC, McCluskey J. Hierarchical self-tolerance to T cell determinants within the ubiquitous nuclear self antigen La (SS-B) permits induction of systemic autoimmunity in normal mice. J Exp Med. 1996;184:1857–70. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.5.1857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Topfer F, Gordon T, McCluskey J. Characterisation of the mouse autoantigen La (SS-B): Identification of conserved RNA binding motifs, a putative ATP binding site and reactivity of recombinant protein with poly(U) and human autoantibodies. J Immunol. 1993;150:3091–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Farris AD, Brown L, Reynolds P, Harley JB, James JA, Scofield RH, McCluskey J, Gordon TP. Induction of autoimmunity by multivalent immunodominant and subdominant T cell determinants of La (SS-B) J Immunol. 1999;162:3079–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.White J, Kappler J, Marrack P. Production and characterization of T cell hybridomas. Meth Mol Biol. 2000;134:185–93. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-682-7:185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vremec D, Shortman K. Dendritic cell subtypes in mouse lymphoid organs: cross-correlation of surface markers, changes with incubation, and differences among thymus, spleen, and lymph nodes. J Immunol. 1997;159:565–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.den Haan JM, Bevan MJ. Constitutive versus activation-dependent cross-presentation of immune complexes by CD8(+) and CD8(−) dendritic cells in vivo. J Exp Med. 2002;196:817–27. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aplin BD, Keech CL, de Kauwe AL, Gordon TP, Cavill D, McCluskey J. Tolerance through indifference: autoreactive B cells to the nuclear antigen La show no evidence of tolerance in a transgenic model. J Immunol. 2003;171:5890–900. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.11.5890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cohen PL, Caricchio R, Abraham V, et al. Delayed apoptotic cell clearance and lupus-like autoimmunity in mice lacking the c-mer membrane tyrosine kinase. J Exp Med. 2002;196:135–40. doi: 10.1084/jem.20012094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Casciola-Rosen LA, Miller DK, Anhalt GJ, Rosen A. Specific cleavage of the 70-kDa protein component of the U1 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein is a characteristic biochemical feature of apoptotic cell death. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:30757–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mevorach D, Zhou JL, Song X, Elkon KB. Systemic exposure to irradiated apoptotic cells induces autoantibody production. J Exp Med. 1998;188:387–92. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.2.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sato A, Iwasaki A. Induction of antiviral immunity requires Toll-like receptor signaling in both stromal and dendritic cell compartments. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:16274–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406268101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]