Abstract

RSV causes annual epidemics of bronchiolitis in winter months resulting in the hospitalization of many infants and the elderly. Dendritic cells (DCs) play a pivotal role in coordinating immune responses to infection and some viruses skew, or subvert, the immune functions of DCs. RSV infection of DCs could alter their function and this could explain why protection after natural RSV infection is incomplete and of short duration. In this study, this interaction between DCs and RSV was investigated using a human primary culture model. DCs were generated from purified healthy adult volunteer peripheral blood monocytes. Effects of RSV upon DC phenotype with RSV primed DCs was measured using flow cytometry. Changes to viability and proliferation of cocultured DCs and T-cells were determined using microscopy with fluorescent dyes (Hoechst 33342 and propidium iodide). DC maturation was not prevented by the RSV challenge. RSV infected a fraction of DCs (10–30%) but the virus replicated slowly in these cells with only small reduction to cell viability. DCs challenged with RSV stimulated T-cell proliferation less well than lipopolysaccharide. This is the first study to demonstrate RSV infection of human monocyte derived DCs and suggests that the virus does not significantly interfere with the function of these cells and potentially may promote cellular rather than humoral responses.

Keywords: respiratory syncytial virus, human dendritic cells, bronchiolitis

Introduction

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) causes annual epidemics of respiratory disease affecting the whole population [1–7]. This virus infects many infants during the first winter after their birth and it has long been recognized that RSV infection is responsible for the majority of cases of acute bronchiolitis and viral pneumonia in infancy.

DCs are professional antigen presenting cells and are central to the induction of immune responses and reside at sites of antigen encounter. In their immature form they specialize in antigen capture and processing. Contact with antigen triggers maturation and the DCs migrate to draining lymph nodes where they potently activate the proliferation of naïve T-cells. DCs exist in networks at mucosal surfaces and are the immune cell most likely to have the early contact following viral infection [8]. New evidence from animal studies suggests that there is a sustained increase in pulmonary dendritic cells following respiratory virus infection in mice [9]. Lying within mucosal surfaces, the DCs are also prime targets for a virus to exploit immune responses.

Viral interactions with DCs have been described as a double-edged sword [10] in which the DC either activates effective immunity or succumbs to the virus, which may interfere with (or suppress) effective immunity. Many viruses such as Measles and Herpes simplex virus-1 have developed mechanisms to interfere with the function of DCs to evade the host immune response either by causing the death of the DC or impairing the activation of immunity and the development of long-term immune memory [11,12,13–16]. Recent studies suggested that bovine RSV (BRSV) does not replicate in bovine MoDCs but does affect their survival [17]. In humans, it has been demonstrated that RSV infects ∼37% of human monocytes and 35% of alveolar macrophages (AM's) [18] but the effects on cell viability were not recorded.

Non-cytotoxic viral infection of DCs is reported to interfere with their capacity to orchestrate immune responses by interfering with expression of key costimulatory molecules on the cell surface as well as proteins involved with antigen presentation. This mechanism could also tilt the immune response or prevent the development of long-term immunological memory. It has been reported that RSV infects human cord blood derived DCs [19]. However, there have been no studies investigating whether RSV infects human monocyte derived dendritic cells (MoDCs) and whether this could modify their maturation or interaction with T cells. It has been reported that immature human MoDCs share similar phenotype and function to human lung DC's [20].

Recent studies of BRSV have reported that the virus lowers the expression of MHC class I and II, CD80 and CD86 in infected bovine MoDCs [17]. It has also been reported that human cord blood DCs show enhanced expression of MHC class I and II, CD80, CD86, CD40 and CD83 in the presence of RSV [19]. However, the effect of RSV (free of contaminating cytokines and waste products) upon differentiation of human MoDCs has not been reported.

IL-12 produced by DCs in the presence of an invading pathogen induces T-cells to produce IFN-γ and other Th1 cytokines including IL-2 and TGF-β[21,22] promoting cytotoxic immune responses needed to destroy cells containing replicating viruses [23]. However, some viruses inhibit DCs from secreting IL-12, promoting their survival [11,14,24–28].

It has been observed that bovine MoDCs infected with BRSV showed a 0·5 fold increase in mRNA expression for IL-12p40 compared to uninfected cells [17]. Another group has demonstrated low level expression of the biologically active from of IL-12 (IL-12p70) by cord blood derived human DCs in the presence RSV [19]. However, this expression was not compared to IL-12 secretion by control uninfected DCs. To date, there have been no published studies investigating whether RSV has the ability to alter IL-12 expression by human MoDCs. Furthermore, there have also been no studies investigating whether RSV infected human MoDCs have the ability to stimulate and proliferate T-cells. Immunological protection against RSV has been regarded as incomplete and of short duration [29], consequently the aim of this study was to investigate whether RSV affected MoDC maturation activation of T-cells.

Materials and methods

Generation of MoDCs

Human peripheral blood was obtained from 6 healthy volunteers with informed consent. 40–100 ml of peripheral blood was removed by venepuncture, heparinized and diluted 1/2 in wash buffer (endotoxin free PBS without Ca2+ and Mg2+ containing 2% heat inactivated foetal calf serum; Gibco BRL, Paisley, UK). Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated by centrifugation over Histopaque™ 1077 (Sigma Chemical Co., Poole, UK) followed by three washes in wash buffer. Monocytes were isolated by magnetic negative selection (StemSep™, StemCell Technologies) according to the manufacturers instructions. Monocytes were routinely 85–90% CD14 positive using this isolation procedure.

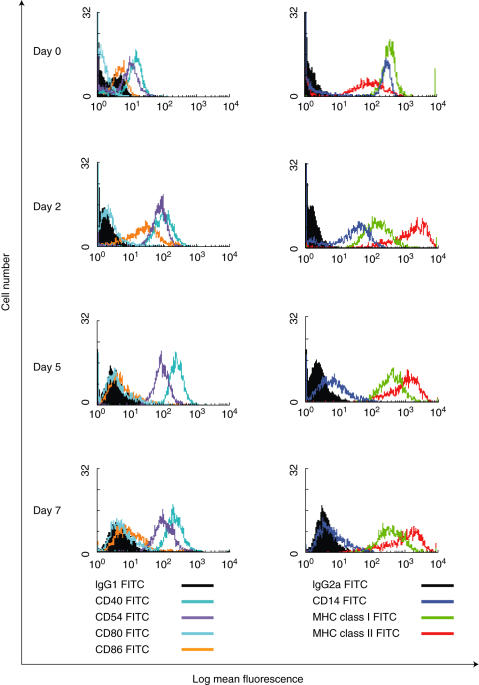

Monocytes were seeded at a density of 1 × 106 cells/ml in serum free X-Vivo-20™ (BioWhittaker, Wokingham, Berkshire) in 24 well flat bottomed plates (Corning Costar, High Wycombe, UK). Cells were supplemented with 40 ng/ml GM-CSF and 20 ng/ml IL-4 (Biosource International, Nivelles, Belgium) and were cultured at 37 °C in a 5% CO2/air mix Sanyo humidified incubator for 5–7 days for DC generation. Cultures were given 50% fresh media containing cytokines twice weekly. The phenotype of MoDCs generated by the serum free culture conditions in this study is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Flow cytometry data to show the phenotypic differentiation of monocytes (day 0) into immature MoDCs over 7 days of culture. Differentiating cells were stained with FITC conjugated antibodies (□) and matched isotype controls (▪) on day 0, 2, 5 and 7. Results are representative of three independent experiments using different volunteer DCs.

RSV production and purification

Respiratory Syncytial Virus was routinely propagated by infection of HeLa cells. Sub-confluent layers of HeLa cells (60–80%) were infected with A2 strain RSV at 37 °C in 2% FCS containing Dulbecco's Modified Eagles Medium (DMEM) until syncytia developed (∼ 5 days). The media was removed and the cells harvested by extensive scraping of the monolayer. RSV virions were released from the HeLa cells by a freeze/thaw cycle and sonication using an ultrasonics Sonicor. Cell debris was separated from the released RSV by centrifugation.

RSV was purified from contaminating proteins and HeLa cell waste products using a rapid centrifugal diafiltration system (developed in house by Dr E Bataki, University of Sheffield, UK). It has been previously demonstrated using sensitive silver staining of proteins in SDS PAGE gels that this washing of the virus extracts successfully removed proteins < 1000 kD as well as removing IL-8 [30]. Briefly, Vivaspin-20™ filters (Vivascience, Sartorius Group) with a 20 ml volume capacity and a pore size of 1 × 106 kD were primed by washing the polyethersulphone membranes in serum free DMEM medium before coating with a 0·1% solution of casein (I-block, Tropix-Perkin-ELMER, Applied Biosystems, Warrington, UK). After washing the filters again with serum free DMEM, a 1/20 solution of crude RSV in serum free media was added to each filter. Centrifugation at 2500 rcf for 40 min at 4 °C resulted in contaminating cytokines and HeLa cell waste products passing through the membrane into the lower chamber (filtrate) and purified RSV remained in the top chamber (retentate) Aliquots of 1/2 or 1/4 purified RSV in serum free media were stored at −70 °C.

Infectivity of RSV stocks was determined by immuno-plaque assay whereby HeLa cells were inoculated with serial dilutions of RSV. Infection was detected with a primary mixed monoclonal RSV antibody (Novocastra, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK), a secondary goat antimouse peroxidase conjugate antibody and a 4-chloronapthol substrate (both obtained from Sigma Chemical Co.). Infectivity was expressed as the number of plaque forming units formed by 1 ml of RSV (pfu/ml).

Some experiments required nonreplicating RSV as a control and this was achieved by exposing thawed aliquots of purified RSV to 240 V of UV light on a FotoPrepI transilluminator for 10 min. Inactivation was verified by complete inhibition of plaque formation when tested in the immuno-plaque assay. RSV replication was also prevented in some experiments by addition of 500 µg/ml of humanized mouse anti-F glycoprotein antibody (Palivizumab) to 1·6 × 105 pfu/ml purified RSV (a kind gift from Abbott Laboratories, Berkshire, UK). This concentration was shown to completely inhibit formation of plaques in the immuno-plaque assay.

Maturation of MoDCs

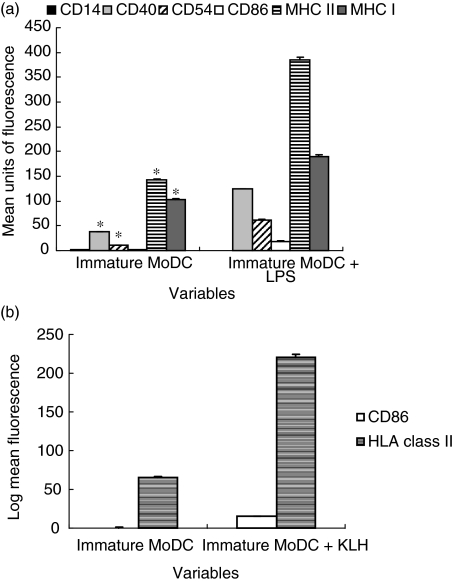

For some experiments, MoDCs were matured between days 5–8 of culture. DC maturation was induced by addition of either 1 µg/ml lipopolysaccharide (LPS) from E. coli 026:B6 together with 2% autologous platelet free plasma or 100 µg/ml Keyhole Limpet Haemocyanin (KLH) (both purchased from Sigma Chemical Co.) for 48 h. The phenotype of mature MoDCs generated by addition of 1 µg/ml LPS and 100 µg/ml KLH is shown in Fig. 2a,b. Addition of LPS to DCs is a widely accepted method to induce effective DC maturation and this probably occurs due to Toll-like-receptor (TLR) signalling and is not dependant upon internalization of LPS by DCs. As internalization of foreign antigens is required for DCs to mature within the airway, endotoxin free KLH was also used to induce DC maturation [31] for comparison purposes as this highly immunogenic protein antigen (which is often used as an adjuvant in vaccines) requires internalization to promote DC maturation. Purified RSV was added to MoDCs at concentrations of 1·6 × 104−5 × 105 pfu/ml on days 5–8 for comparison of MoDC maturation.

Fig. 2.

Maturation of DCs (a) DC maturation by addition of 1 µg/ml LPS. DCs were stained with matched isotype controls and each bar represents the subtracted matched isotype mean fluorescence values for each antibody. The error bars represent the standard error of the mean fluorescence measurements and *significance at P < 0·001 compared to MoDCs cultured with LPS. Results are representative of six independent experiments using different volunteer DCs. (b) DC maturation by addition of 100 µg/ml KLH. DCs were stained with matched isotype controls and each bar represents the subtracted matched isotype mean fluorescence values for each antibody. The error bars represent the standard error of the mean fluorescence measurements and *significance at P < 0·001 compared to MoDCs cultured with KLH. Results are representative of three independent experiments using different volunteer DCs.

Viability staining

MoDC viability was assessed by incubation of the cells with medium containing Hoechst 33342 (Sigma Chemical Co.) and propidium iodide (PI) (Molecular Probes, Cambridge Biosciences, Cambridge, UK) at final concentrations of 10 µM and 20 µM, respectively. After 10 min incubation at 37 °C, the MoDCs were visualized under a Leica DMIRB UV fluorescent inverted microscope using the UV filter. Viable cells appeared morphologically normal and were stained blue. Apoptotic cells with intact plasma membranes stained with Hoechst 33342 but displayed morphology characteristic of apoptotic cells including DNA condensation and fragmentation of nuclei. Late apoptotic cells stained blue/pink as they were both Hoechst 33342 and propidium iodide positive due to partial loss of membrane integrity. Necrotic cells stained only with propidium iodide and appeared as bright red with swollen nuclei.

Cell numbers were counted using a Whipple graticule in the microscope eyepiece and placing this randomly over several areas within each well, with a minimum of three replicate wells for each measurement (Pyser-SGI, Edewbridge, UK). The mean counts of viable, necrotic and apoptotic cells were derived and the total numbers of each type of cell per well determined (Mean graticule cell count = Area of well/area of graticule). The viable, apoptotic and necrotic cells were expressed as a percentage of the total number of cells counted.

Flow cytometry

For investigation of MoDC surface antigen expression, cells were carefully removed from culture by gentle pipetting, washed and spun to pellet. MoDCs were then resuspended in wash buffer (PBS containing 0·1% bovine serum albumin [BSA]) at concentration of 1 × 106 cells/ml. Cells were placed in 200 µl volumes into each tube and were again spun to pellet. Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) conjugated monoclonal antibodies specific for HLA class I (ABC) and II (DQ, DP, DR) (Serotec, Kidlington, Oxford, UK), CD54, CD14 (Dako, Ely, Cambridgeshire, UK) and CD86 (Ancell Corporation, Bayport, USA) were used for surface staining together with matched isotype controls. All monoclonal antibody solutions and isotype controls were standardized to a concentration of 10 µg/ml of IgG by dilution in wash buffer and 100 µl volumes were added to the cell pellets. After vortexing and incubation on ice for 30 min in the dark, cells were washed free of unbound antibody by two washes in buffer and subsequent centrifugation. Surface stained MoDCs were resuspended in wash buffer for analysis.

To stain for intracellular RSV antigen expression MoDCs were re-suspended in wash buffer at 1 × 106 cells/ml and were fixed in 4 °C 50% acetone, 50% PBS solution. The cells were added drop-wise to the acetone:PBS whilst the fixative solution was subject to vortex at low speed to ensure a single cell suspension during permeabilization and fixation. The fixative solution was removed from the MoDCs by addition of wash buffer, centrifugation and aspiration of the supernatant. MoDCs were stained with a previously determined optimal dilution (1/50) of the purified mixed monoclonal antibody (Novocastra, Newcastle, UK; specific for the phosphoprotein (P), fusion protein (F) and nuclear protein (N) of (RSV) and incubated for 30 min on ice in the dark. Cells were washed free of unbound antibody as above and were subsequently stained with 10 µg/ml of antimouse FITC antibody (Sigma Chemical Company, Poole, UK) for 30 min on ice in the dark. The cells were then washed three times and re-suspended in 200 µl volumes of wash buffer.

Cells were analysed using a Coulter Epics ELITE ESP flow cytometer measuring fluorescence emission at 525 nm. Cell fragments or clusters of cells were excluded from acquisition and MoDCs were gated using a forward scatter versus side scatter plot. Data was expressed using WinMDI flow cytometry version 2·8 software.

T-cell proliferation assays

T-cells were isolated from a different volunteer to the DC donor (allogeneic). Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were isolated as above by centrifugation and T-cells were isolated by magnetic negative selection (StemSep™, StemCell Technologies) according to the manufacturers instructions. T-cells were routinely 95% CD3 positive using this isolation procedure.

One × 105 T-cells were cocultured with 4 × 104 MoDCs (primed with LPS, KLH or RSV) at a ratio of 2·5 : 1 in triplicate wells in X-Vivo-20™ media for 7 days at 37 °C in a 5% CO2/air mix Sanyo humidified incubator. After 7 days, cell viability was measured by staining with Hoechst 33342 and propidium iodide. Cell numbers were calculated using a Whipple graticule calibrated with a stage micrometer. Total cell numbers were calculated as previously described.

Data analysis and statistics

Data generated from this study was expressed as mean ± standard error (SE) or percentage (%) of positive stained cells. All data was assessed for significance using SigmStat® statistical software, version 2·0. Parametric flow cytometry data and data derived from T-cell proliferation assays was analysed using paired t-tests. Data was only considered significant at P < 0·001 for flow cytometry data due to the large sample size for each measurement. Comparisons of proportions of positive stained cells between variables were analysed using the z-test. Again, flow cytometry proportion data was only considered significant at P < 0·001.

Results

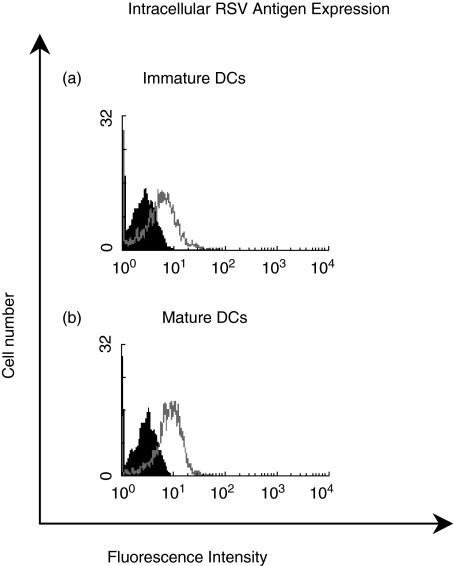

RSV is detectable inside both immature and mature MoDCs after incubation

The ability of CD1a positive immature MoDCs to internalize RSV was investigated. Immature MoDCs were generated over 7 days and incubated with 5 × 105 pfu/ml purified RSV for 30 min at 37 °C. LPS matured MoDCs were also incubated with an identical titre of RSV for comparison. Internalization of RSV was stopped after 30 min by addition of ice-cold FACS buffer to both cell populations followed by copious washing. Immature and mature MoDCs were fixed and permeabilized with acetone/PBS solution and were stained for intracellular RSV antigens. MoDCs were also left unfixed (and nonpermeabilized) to investigate cell surface RSV antigen expression.

Unfixed MoDCs (immature and mature) that had been incubated with RSV did not stain for RSV antigens. Staining for RSV antigens was only observed in MoDCs that had been fixed and permeabilized demonstrating that RSV antigens were present intracellularly. Immature MoDCs efficiently internalized RSV as shown by the increase in fluorescence compared to the minus primary antibody control (Fig. 3a). A similar increase in fluorescence was observed for mature MoDCs (Fig. 3b), suggesting that RSV was present within both immature and LPS matured MoDCs within 30 min of incubation with the virus.

Fig. 3.

Internalization of 5 × 105 pfu/ml purified RSV by (a) immature DC and (b) mature DC after 30 min of incubation at 37°C (□); DCs incubated with RSV but stained only with the secondary antimouse FITC antibody (minus primary antibody controls)(▪). Results are representative of three independent experiments using different volunteer DCs.

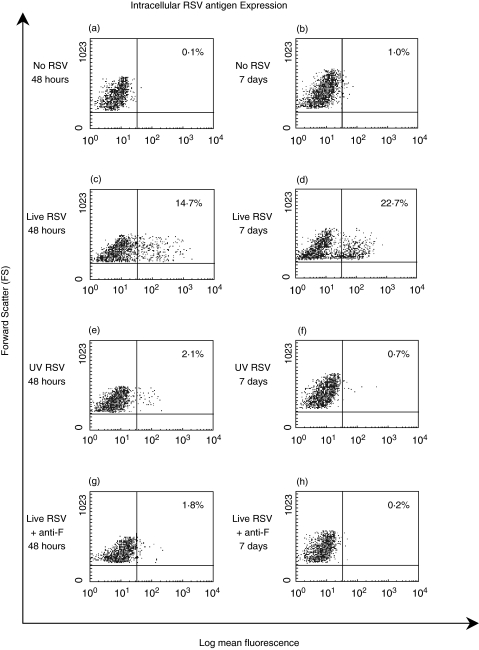

RSV productively infects MoDCs

RSV antigens were detected inside immature and mature MoDCs at similar levels. To demonstrate that there was an increase in the viral content of these cells, immature MoDCs were infected with 1·6 × 105 pfu/ml RSV or 1·6 × 105 pfu/ml UV inactivated RSV. The specificity of the staining was also demonstrated by adding RSV (1·6 × 105 pfu/ml) with 500 µg/ml of mouse anti-RSV F glycoprotein (Palivizumab) for 10 min before addition to the MoDCs. MoDCs were also incubated in the absence of RSV to assess nonspecific staining. The cells were fixed and permeabilized and stained for intracellular RSV antigens at time points of 48 h and 7 days.

The percentage of MoDCs that positively stained for intracellular RSV antigens after 48 h and 7 days of culture is shown in Fig. 4. In the absence of RSV, unstained MoDCs increased their auto-fluorescence between 48 h and 7 days (data not shown) and so at each time point the staining for RSV infected cells was corrected using the non specific staining observed at the same time point. After 48 h of culture with live purified RSV, 10–20% (n = 3) of the MoDCs stained positive for intracellular RSV antigens (Fig. 4c). In the presence of nonreplicating UV inactivated purified RSV at the same titre, the percentage of positive cells was significantly lower at 1–3% (P < 0·001) (n = 3) (Fig. 4e) The positive staining associated with live RSV (10–20% (n = 3) (Fig. 4c) was significantly blocked (P < 0·001) by the anti-F-glycoprotein antibody with only 1–2·5% (n = 3) cells stained (Fig. 4g).

Fig. 4.

Flow cytometry data to compare the percentage of DCs positive for intracellular RSV antigens after 48 h and 7 days (a, b) in the absence of RSV and (c, d) in the presence of 1·6 × 105 pfu/ml purified RSV (live RSV); (e, f) 1·6 × 105 pfu/ml UV inactivated purified RSV and (g, h) 1·6 × 105 pfu/ml purified RSV incubated with a humanized anti-F glycoprotein blocking antibody. The plots on the left show DCs after 48 h of incubation compared to the plots on the right that shows DCs after 7 days of incubation. Dead cells and/or cell clusters were excluded from analysis by gating. Results are representative of three independent experiments using different volunteer DCs.

After 7 days of incubation with RSV, the percentage of positive cells staining for RSV increased from 10 to 20% (Fig. 4c) to 20–30% (P < 0·001) (Fig. 4d), showing that MoDCs were still capable of replicating RSV on day 11 of culture (RSV was added on day 4). MoDCs incubated with UV inactivated RSV showed a reduction in positive staining after 7 days (0–2%; Fig. 4f) compared to 48 h of incubation (1–3%, Fig. 4e). A significant reduction in staining was also observed between day 2 and day 7 after infection when the RSV was added with the anti-F glycoprotein antibody.

To establish whether infected MoDCs produced RSV that was capable of infecting and replicating in other cells 105 immature MoDCs were challenged with 1 × 104 pfu/ml of RSV and left for 7 days. These cells were then harvested, washed, and cocultured with HeLa cells for 3 days. An equivalent titre of RSV was added to equivalent numbers of HeLa cells directly and at the end of this period the RSV plaque number was determined by immunostaining. From the infected MoDC the range of plaques varied from 5 to 9 × 104/pfu/ml whereas this titre of RSV added directly to the HeLa cells produced a range from 20 to 30 × 106 pfu/ml.

RSV induced DC maturation

Although RSV productively infected a population of MoDCs, it was questioned as to whether RSV interfered with the maturation of MoDCs. Immature MoDCs were supplemented with 1·6 × 104 pfu/ml purified RSV and then compared to control MoDCs in the absence of RSV. After 48 h of incubation, MoDCs were stained with FITC conjugated antibodies to CD14, CD54, CD86 and HLA classes I and II. Increases to the expression of all surface molecules (except CD14) were observed in the presence of RSV compared to the control MoDCs (Table 1). Taken together, these results demonstrated that challenge with RSV had stimulated maturation of the MoDCs.

Table 1.

Phenotypic characteristics of monocyte derived DCs after 48 h of culture in the absence and presence of 1·6 × 104 pfu/ml RSV. Mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) values have been corrected by subtraction of matched isotype controls from each measurement. Results are representative of three independent experiments using different volunteer DCs.

| Mean fluorescence intensity (± SE) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Control DCs | RSV DCs | |

| CD86 | 0·1 ± 0·01 | 5·4 ± 0·1* |

| CD54 | 8·6 ± 0·1 | 42·6 ± 0·4* |

| HLA class I | 50·3 ± 1·2 | 77·9 ± 1·7* |

| HLA class II | 42·8 ± 0·8 | 49·4 ± 1·1* |

| CD14 | 1·3 ± 0·1 | 0·5 ± 0·01* |

P < 0·001 compared to controls.

RSV induced T-cell proliferation

To investigate whether RSV incubated MoDCs were able to proliferate T-cells, immature MoDCs were supplemented with 2·4 × 105 pfu/ml purified RSV, 100 µg/ml KLH, or 1 µg/ml LPS and were incubated for 48 h. The primed MoDCs were then cultured with allogeneic T-cells at a ratio of 1–2·5 for a further 7 days. T-cells and MoDCs from each of the variables were also cultured alone as controls. After 7 days of culture, the total cell numbers from each variable were counted by staining of the viable, apoptotic and necrotic cells with Hoechst 3342 and PI.

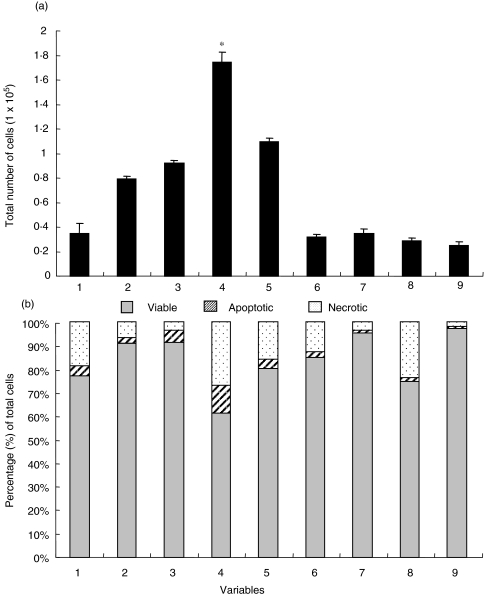

Figure 5 shows results from a typical allogeneic T-cell and MoDCs coculture. These two cell types did not proliferate over 7 days when cultured alone. Total cell numbers from KLH primed cocultures were comparable with total cell numbers from the control cocultures. However, there was a large significant (P < 0·01) increase in cell number after LPS primed MoDCs were cocultured with T-cells compared to the control cocultures. Although T- cells cocultured with RSV primed MoDCs proliferated, they did not proliferate as well as T-cells cocultured with LPS MoDCs. Figure 3b shows the percentage of viable, apoptotic and necrotic cells for each variable after 7 days of coculture with allogeneic T-cells. Levels of cell death (apoptosis and necrosis) were generally less than 20% apart from those cultures treated with LPS where larger number of dead cells were observed.

Fig. 5.

(a) Allogeneic T-cell proliferation induced by day 7 DCs primed with KLH, LPS and 2·4 × 105 pfu/ml purified RSV. DCs were cocultured with T-cells at a ratio of 1 : 2·5. The error bars represent the standard error between the mean total cell counts derived from counting 3 areas in triplicate wells of a 96 well plate and *significance at P < 0·001 compared to cocultured control MoDCs. (b) Graph to show the percentages of viable, apoptotic and necrotic cells after the T-cell proliferation assay (as shown in (a)) as assessed by staining with Hoechst 33342 and propidium iodide. Results are representative of nine independent experiments.

Discussion

This study has shown that RSV has the ability to infect both immature and mature human MoDCs productively but without these cells losing their viability in large numbers or altering their differentiation and immune regulatory function. The results also suggest that RSV may persist in MoDCs. This is the first study to report in detail these effects of RSV upon human MoDCs.

The finding that RSV antigens were present within both immature and mature DCs after 30 min of incubation was interesting given that fact that mature DCs are significantly less able to capture antigens than immature DCs. However, this phenomenon was also observed in other independent experiments with different volunteer mature DCs exhibiting the phenotype of typical LPS matured DCs (high expression of HLA class I and II and increases in expression CD86, CD40 CD54). It was not observed when FITC dextran was incubated with LPS matured DCs (data not shown). These results suggest that RSV may gain entry into DCs via a specific cell surface antigen instead of via a pinocytic pathway. Another paramyxovirus, Measles virus, gains access to DCs by binding to the surface receptor CD46 before fusing with the membrane via the F-protein [32]. In addition, a study by Behera et al. [33] has demonstrated that CD54 facilitates RSV entry and infection of human epithelial cells by binding to the viral F-glycoprotein. Further work is required to investigate the hypothesis that RSV uses CD54 or other surface antigens to gain entry into mature MoDCs for viral replication.

The cellular content of RSV antigens increased in the MoDCs 48 h after infection but not when the cells were sham infected with UV inactivated RSV. If the RSV had accessed MoDCs without replicating, a decrease in RSV staining over time might have been expected. Instead the mean fluorescent intensity of staining and the proportion of positively stained cells increased with time 7 days post infection (Fig. 5). The infection of the DCs was specifically blocked by pre incubation of the RSV with the anti-RSV F-glycoprotein antibody.

There was a variation between different donors in the percentage of MoDCs that stained for RSV antigens (ranging from 10 to 30%), suggesting that a variable subpopulation of cells was susceptible to infection (or replication). These results concur with previous reports that RSV infected ∼30% of alveolar macrophages and monocytes [18]. Bartz et al. [19] also reported that RSV infected ∼10% of human cord blood derived DCs but this was examined only 24 h post infection and the increasing expression of RSV antigens over time was not demonstrated. BMDCs were reported not to support BRSV replication by Werling et al. [17] who used plaque assays to detect viral replication. However, they did not use flow cytometry to detect individual cells and may therefore have missed a sub population of infected cells too small to produce sufficient virus to detect using a plaque assay.

It is not clear why a fraction of the MoDCs were permissive to RSV replication but this may be due to variations in phenotype and maturation. If maturation of cultured MoDC was asynchronous the immature cells may have been better protected, as they would be more active in the uptake and processing of foreign antigens. Mature DCs down-regulate these antigen processing functions and may posed better targets for RSV infection. However when both mature and immature cells were infected with RSV, equivalent amounts of RSV were detected in a sub population of these two MoDC cultures. Compared to respiratory epithelial cells, RSV appeared only to infect a subpopulation of MoDCs and to replicate more slowly within these cells. Whereas equivalent titres of RSV were found to infect every HeLa cell and the bronchial epithelial cells (16HBEo line) resulting in complete destruction of these cells within 4–5 days. This difference suggests a mechanism by which RSV may reside within antigen presenting cells the host for prolonged periods [34,35]. In this present study 7 days after MoDC were infected with RSV they were able to productively infect HeLa cells albeit at a very low level.

The infection (and replication) of RSV within a sub population of MoDCs may have been influenced by the phenotype and maturation of these cells. During their differentiation, CD14 expression by MoDCs reduced in the presence of RSV comparably to LPS, suggesting that exposure promoted normal maturation. The increased expression of maturation markers was also observed in the cells exposed to RSV compared to sham infected cells. This effect was consistent with reports by others [17,19] that RSV does not detrimentally affect the maturation and phenotypic development of DCs from their precursors. Whilst no inhibitory effect upon MoDC maturation was observed, the infection of a subpopulation of the cells may have altered other aspects of their immune regulating functions.

MoDCs primed with RSV stimulated T cell proliferation but less effectively than MoDCs primed with LPS (Fig. 6). A dose dependent increase in T cell proliferation was also observed with increasing titre (from 1·4 × 105 to 2·2 × 106 pfu/ml) of RSV added to the MoDCs (P < 0·012). Variation in proliferation of the T cells was observed between individual donors, but overall MoDCs challenged with RSV stimulated proliferation of T cells to the same or greater extent than KLH but always less than the effect of LPS.

The viability of the MoDCs and T cells in the cocultures was examined to establish if the RSV provoked ‘memory’ cytotoxic responses since most adults experience multiple episodes of RSV infection during their life. Reductions to the viability (∼83% viability) of T cells and MoDCs were seen in the cocultures but more cells died when LPS was added compared to RSV.

In this study DCs were derived from healthy adult volunteer monocytes and these may not adequately represent antigen presenting cells in the infant. Comparison with neonatal cord blood derived DCs may help to resolve whether the maturation and function of these cells is different when they interact with RSV compared to adult ‘monocyte derived’ DCs.

Taking into account that only a proportion of the MoDCs became infected with RSV without large reductions to their viability and function, it could be argued that this virus had no major inhibitory or enhancing impact upon the immune function of these cells. However, the persistence of the virus in a subpopulation of DCs may maintain the virus at subclinically detectable levels.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the financial support of the Sheffield Children's Hospital Children's Appeal. We would like to thank Dr Geoff Toms (Newcastle University, UK) for providing preparations of RSV(A2) and Abbott Laboratories for the supply of the humanized mouse monoclonal anti F glycoprotein antibody (Palivizumab).

References

- 1.Everard ML. Respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis and pneumonia. In: Taussig L, Landau L, editors. Textbook of Paediatric Respiratory Medicine. Mosby: St Louis; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gilchrist S, Torok TJ, Gary HE, Jr, Alexander JP, Anderson LJ. National surveillance for respiratory syncytial virus, United States 1985–90. J Infectious Dis. 1994;170:986–90. doi: 10.1093/infdis/170.4.986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Falsey AR, Walsh EE. Respiratory syncytial virus infection in adults. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2000;13:371–84. doi: 10.1128/cmr.13.3.371-384.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Everard ML, Swarbrick A, Wrightham M, McIntyre J, Dunkley C, James PD, Sewell HF, Milner AD. Analysis of cells obtained by bronchial lavage of infants with respiratory syncytial virus infection. Arch Dis Childhood. 1994;71:428–32. doi: 10.1136/adc.71.5.428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith PK, Wang SZ, Dowling KD, Forsyth KD. Leucocyte populations in respiratory syncytial virus-induced bronchiolitis. J Paediatrics Child Health. 2001;37:146–51. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1754.2001.00618.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Viuff B, Tjornehoj K, Larsen L, Rontved CM, Uttenthal A, Ronsholt L, Alexandersen S. Replication and clearance of respiratory syncytial virus: apoptosis is an important pathway of virus clearance after experimental infection with bovine respiratory syncytial virus. Am J Pathol. 2002;161:2195–207. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64496-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Byrd LG, Prince GE. Animal models of respiratory syncytial virus infection. Clin Infectious Dis. 1997;25:1363–8. doi: 10.1086/516152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klagge IM, Schneider-Schaulies S. Virus interactions with dendritic cells. J General Virol. 1999;80:823–33. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-80-4-823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beyer M, Bartz H, Horner K, Doths S, Koerner-Rettberg C, Schwarze J. Sustained increases in number of pulmonary dendritic cells after respiratory syncytial virus infection. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;113:127–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2003.10.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bhardwaj N. Interactions of viruses with dendritic cells: a double-edged sword. J Exp Med. 1997;186:795–9. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.6.795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fugier-Vivier I, Servet-Delprat C, Rivailler P, Rissoan M-C, Liu Y-J, Rabourdin-Combe C. Measles virus suppresses cell-mediated immunity by interfering with the survival and functions of dendritic and T cells. J Exp Med. 1997;186:813–23. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.6.813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mikloska Z, Bosnjak L, Cunningham AL. Immature monocyte-derived dendritic cells are productively infected with herpes simplex virus type 1. J Virol. 2001;75:5958–64. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.13.5958-5964.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Salio M, Cella M, Suter M, Lanzavecchia A. Inhibition of dendritic cell maturation by herpes simplex virus. European J Immunol. 1999;29:3245–53. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199910)29:10<3245::AID-IMMU3245>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Andrews DM, Andoniou CE, Granucci F, Ricciardi-Castagnoli P, Degli-Esposti MA. Infection of dendritic cells by murine cytomegalovirus induces functional paralysis. Nature Immunol. 2001;2:1077–84. doi: 10.1038/ni724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moutaftsi M, Mehl AM, Borysiewicz LK, Tabi Z. Human cytomegalovirus inhibits maturation and impairs function of monocyte-derived dendritic cells. Blood. 2002;99:2913–21. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.8.2913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grigoleit U, Riegler S, Einsele H, et al. Human cytomegalovirus induces a direct inhibitory effect on antigen presentation by monocyte-derived immature dendritic cells. Br J Haematol. 2002;119:189–98. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2002.03798.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Werling D, Collins RA, Taylor G, Howard CJ. Cytokine responses of bovine dendritic cells and T cells following exposure to live or inactivated bovine respiratory syncytial virus. J Leukocyte Biol. 2002;72:297–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Midulla F, Huang YT, Gilbert IA, Cirino NM, McFadden ER, Panuska JR. Respiratory syncytial virus infection of human cord and adult blood monocytes and alveolar macrophages. Am Rev Respiratory Dis. 1989;140:771–7. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/140.3.771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bartz H, Buning-Pfaue F, Turkel O, Schauer U. Respiratory syncytial virus induces prostaglandin E2, IL-10 and IL-11 generation in antigen presenting cells. Clin Exp Immunol. 2002;129:438–45. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2002.01927.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cochland L, Isler P, Songeon F, Nicod LP. Human lung dendritic cells have an immature phenotype with efficient mannose receptors. Am J Respiratory Cell Mol Biol. 1999;21:547–54. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.21.5.3785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stockwin LH, McGonagle D, Martin IG, Blair GE. Dendritic cells. immunological sentinels with a central role in health and disease. Immunol Cell Biol. 2000;78:91–102. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1711.2000.00888.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Trinchieri G. The two faces of interleukin 12: a pro-inflammatory cytokine and a key immunoregulatory molecule produced by antigen-presenting cells. Ciba Found Symp. 1995;195:203–14. doi: 10.1002/9780470514849.ch14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Trinchieri G. Proinflammatory and immunoregulatory functions of interleukin-12. Int Rev Immunol. 1998;16:365–96. doi: 10.3109/08830189809043002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grosjean I, Caux C, Bella C, Berger I, Wild F, Banchereau J, Kaiserlian D. Measles virus infects human dendritic cells and blocks their allostimulatory properties to CD4+ T cells. J Exp Med. 1997;186:801–12. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.6.801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Steineur MP, Grosjean I, Bella C, Kaiserlian D. Langerhans are susceptible to measles virus infection and actively suppress T cell proliferation. European J Dermatol. 1998;8:413–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Macatonia SE, Gompels M, Pinching AJ, Patterson S, Knight SC. Antigen-presentation by macrophages but not by dendritic cells in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. Immunology. 1992;75:576–81. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kruse M, Rosorius O, Kratzer F, Stelz G, Kuhnt C, Schuler G, Hauber J, Steinkasserer A. Mature dendritic cells infected with herpes simplex virus type 1 exhibit inhibited T-cell stimulatory capacity. J Virol. 2000;74:7127–36. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.15.7127-7136.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Plotnicky-Gilquin H, Cyblat D, Aubry JP, Delneste Y, Blaecke A, Bonnefoy JY, Corvaia N, Jeannin P. Differential effects of parainfluenza virus type 3 on human monocytes and dendritic cells. Virology. 2001;285:82–90. doi: 10.1006/viro.2001.0933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hall CB, Walsh EE, Long CE, Schnabel KC. Immunity to and frequency of reinfection with respiratory syncytial virus. J Infectious Dis. 1991;163:693–8. doi: 10.1093/infdis/163.4.693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bataki EL, Everard ML, Evans GS. Respiratory Syncytial Virus and Neutrophil Activation. Clin Exp Immunol. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2005.02780.x. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Geiger JD, Hutchinson RJ, Hohenkirk LF, et al. Vaccination of pediatric solid tumour lysate-pulsed dendritic cells can expand specific T cells and mediate tumour regression. Cancer Res. 2001;61:8513–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dorig RE, Marcil A, Chopra A, Richardson CD. The human CD46 molecule is a receptor for measles virus (Edmonston strain) Cell. 1993;75:295–305. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)80071-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Behera AK, Matsuse H, Kumar M, Kong X, Lockey RF, Mohapatra SS. Blocking intercellular adhesion molecule-1 on human epithelial cells decreases respiratory syncytial virus infection. Biochem Biophys Res Comms. 2001;280:188–95. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.4093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Valarcher JF, Bourhy H, Lavenu A, Bourges-Abella N, Roth M, Andreoletti O, Ave P, Schelcher F. Persistent infection of B lymphocytes by bovine respiratory syncytial virus. Virology. 2001;291:55–67. doi: 10.1006/viro.2001.1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cubie HA, Duncan LA, Marshall LA, Smith NM. Detection of respiratory syncytial virus nucleic acid in archival postmortem tissue from infants. Pediatric Pathol Laboratory Med. 1997;17:927–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]