Abstract

IgA nephropathy (IgAN) is the most common primary glomerulonephritis, with various pathological phenotypes. Our previous study suggested that aberrant glycosylation of serum IgA1 was associated with different pathological phenotypes of IgAN, and substantial evidence indicated that deglycosylated IgA1 had an increased tendency to form macromolecules. The aim of the current study was to investigate the composition of IgA1-containing macromolecules in different pathological phenotypes of IgAN. Sera from 10 patients with mild mesangial proliferative IgAN (mIgAN), 10 with focal proliferative sclerosing IgAN (psIgAN) and 10 healthy blood donors were collected. The sera were applied and IgA1 binding proteins (IgA1-BP) were eluted from the columns immobilized with desialylated IgA1 (DesIgA1/Sepharose) or desialylated/degalactosylated IgA1 (DesDeGalIgA1/Sepharose), respectively. The amounts of IgA1 and IgG and the glycoform of IgA1 in the IgA1-BP were detected by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) and were compared between patients with different pathological phenotypes and normal controls. The amount of IgA1 in IgA1-BP eluted from both columns was significantly higher in patients with both pathological phenotypes of IgAN than in normal controls. In IgA1-BP eluted from DesDeGalIgA1/Sepharose, the desialylation of IgA1 was much more pronounced in patients with both pathological phenotypes of IgAN than in normal controls, while the degalactosylation of IgA1 was much more pronounced only in patients with psIgAN than in normal controls. Furthermore, the amount of IgG in IgA1-BP eluted from DesDeGalIgA1/Sepharose was significantly higher in patients with psIgAN than in normal controls. In patients with psIgAN, the amount of IgG eluted from DesDeGalIgA1/Sepharose was much greater than from DesIgA1/Sepharose. In conclusion, self-aggregated deglycosylated IgA1 with or without IgG were associated with the development of IgAN.

Keywords: deglycosylation, IgA nephropathy, macromolecular IgA1, pathology

Introduction

IgA nephropathy (IgAN) is the most common form of glomerulonephritis throughout the world. It accounts for 20–45% of primary glomerular diseases. One-third of the patients progress eventually to end-stage renal disease [1,2]. However, the pathogenesis of IgAN remains elusive. Our previous study demonstrated that heat-aggregated serum IgA1 from patients with IgAN had a higher binding capacity to cultured human mesangial cells (HMC) and stronger biological effects than from healthy controls, suggesting that serum IgA1 from patients with IgAN was different to healthy people [3,4].

It is known that there are two subclasses of IgA molecules: IgA1 and IgA2. In contrast to IgG, IgM and IgA2, human serum IgA1 is one of the most exceptional human serum immunoglobulins because of its five O-linked oligosaccharides in its hinge region, in addition to the two N-linked carbohydrate chains in its structure. N-acetylgalactosamine (GalNAc) is linked with serine and/or threonine residues, and galactose (Gal) is linked to GalNAc through an β-1,3 linkage. Sialic acid has an α-2,6 linkage with GalNAc and a α-2,3 linkage with Gal residues [5]. In recent years many studies have demonstrated that the initiating event in the pathogenesis of IgA nephropathy is the deposition of deglycosylated IgA1 subclass [6–13]. Recently, we have also confirmed that the binding capacities of desialylated IgA1 (DesIgA1) and desialylated/degalactosylated IgA1 (DesDeGalIgA1) to HMC were significantly higher than that of normal IgA1 [14]. When analysing the eluent obtained from renal biopsy tissue of IgAN, desialylation and degalactosylation of IgA1 was much more pronounced than serum IgA1 [6,15], which implied that aberrantly glycosylated IgA1 was pathogenic.

It is well known that the pathological phenotypes of IgAN are highly variable. However, the key factors contributing to the presentation of different phenotypes of IgAN remain elusive. Recently, Coppo's speculation that defects in IgA1 glycosylation might influence the presentation and natural history of patients with IgAN [16] emphasized the important pathogenicity of the aberrant glycosylation of IgA1. Our previous study demonstrated that desialylation and degalactosylation of serum IgA1 were much more pronounced in patients with focal proliferative sclerosing IgAN than those in patients with mild mesangial proliferative IgAN and normal controls. It suggested that deglycosylation of serum IgA1 was associated closely with pathological phenotypes of IgAN [17].

In IgAN, deposited IgA1 in the glomerular mesangial region is predominantly macromolecular IgA1 [18]. The levels of serum macromolecular IgA1 may elevate in approximately half of patients with IgAN, but van der Boog et al. has demonstrated that the elevated serum level of macromolecular IgA1 was not a prognostic marker for the progression of IgAN. It was not size alone, but the physicochemical composition of macromolecular IgA1 that was the key factor leading to mesangial deposition [19]. Therefore, macromolecular IgA1 composed of deglycosylated IgA1 and other immunoglobulins might be a contributory factor to the pathogenesis of the disease. The aim of the current study was to investigate the composition of immunoglobulins binding to deglycosylated IgA1 and their association with different pathological phenotypes of IgA nephropathy.

Materials and methods

Patients and sera

Twenty patients with renal biopsy-proven IgAN without any complications were enrolled into the current study. Ten patients presented as mild mesangial proliferative glomerulonephritis (mIgAN) without overt tubular and interstitial damage in renal pathology, fulfilling the criteria of HAAS-I, a pathologic scheme of IgAN proposed by Haas [20]. The other 10 had focal proliferative sclerosing glomerulonephritis (psIgAN) and could be defined as HAAS-III or HAAS-V [20]. In the mesangial deposits, IgA was predominant along with C3. IgG was seen in four patients with IgAN in either group. Sera from the patients were collected upon diagnosis by renal biopsy and were stored at −20°C before use. None of the patients had onset of macroscopic haematuria or with prodromal infections. Sera obtained from 10 healthy blood donors were used as normal controls (NC). Informed consent was obtained from the patients for sampling sera.

Isolation of normal human serum IgA1

IgA1 was isolated from normal human plasma by jacalin affinity chromatography [21]. Briefly, the pooled plasma were diluted 1 : 1 with 0·01 mol/l phosphate buffered saline (PBS), filtered through a 0·22 µm Corning syringe filter (Corning Glass Works, Corning, NY, USA) and then applied to a jacalin column. The column was prepared with commercially available jacalin immobilized on cross-linked 4% beaded agarose (Pierce Chemical Company, Rockford, IL, USA) with an IgA1 binding capacity of more than 2 mg/ml. The column was equilibrated with 175 mmol/l Tris-HCl (PH7·4) and IgA1 was eluted with 0·1 mol/l melibiose (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) in 175 mmol/l Tris-HCl and collected in 2-ml fractions. The fractions were then pooled and concentrated using polyethylene glycol (PEG) 20 000. The concentrated sample was dialysed against distilled water for 24 h to remove melibiose. The sample was proved to be IgA1 by double immunodiffusion and immunoelectrophoresis using goat anti-human IgA1, goat anti-human IgG and goat anti-human IgM (Beckman Coulter Inc, Fullerten, CA, USA) as described previously [3]. The total protein concentration of the sample was tested using the Bradford method. IgA1 was then aliquoted into 1 mg per tube and lyophilized.

Preparation of IgA1, DesIgA1 and DesDeGalIgA1/Sepharose

Five g of CNBr-activated Sepharose 4B (Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden) was washed thoroughly with 2 l of 1 mmol/l HCl at 4°C; 25 mg of IgA1 in 30 ml of coupling buffer (0·1 mol/l NaHCO3 containing 0·5 mol/l NaCl, pH 8·3) was added to about 15 ml of the wet gel and stirred at room temperature for 2 h. The remaining active groups were blocked with 30 ml of 0·2 mol/l glycine buffer (pH 8·0) for 2 h at room temperature and then the gel was divided equally into three aliquots. Each aliquot was packed into a column and was washed with 0·1 mol/l Tri-HCl buffer (pH 7·5) and 0·1 mol/l Tri-HCl containing 1 mol/l NaCl (pH 7·5) alternately until the optical density was less than 0·1. The gel in three columns was then suspended in 50 mmol/l sodium acetate buffer (pH 5·0). The gel in the first column was treated overnight with 320 mU of neuraminidase (Sigma) alone, the gel in the second column was treated with 320 mU of neuraminidase and 100 mU of β-galactosidase (Sigma) and the third was suspended with sodium acetate buffer alone as a control. The gel was then washed thoroughly with 0·1 mol/l Tri-HCl containing 1 mol/l NaCl. The columns were named DesIgA1/Sepharose (immobilized with desialylated IgA1), DesDeGalIgA1/Sepharose (immobilized with desialylated/degalactosylated IgA1) and native IgA1/Sepharose, respectively.

Evaluation of the efficacy of enzyme digestion

Evaluation of the efficacy of enzyme digestion was performed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) using arachis hypogaea (peanut agglutinin, PNA, Sigma) and vilsa villosa lectin (VVL, Vector Lab, Burlingame, CA, USA). These two lectins bind specifically to β1,3-Gal residues and the terminal GalNAc residues, respectively. Thirty µl suspended native IgA1/Sepharose, DesIgA1/Sepharose and DesDeGalIgA1/Sepharose gel in 0·01 mol/l PBS and 70 µl 0·01 mol/l PBS containing 0·1% Tween-20 (PBST) were added to the centrifuge tubes. Each sample was added in duplicate. After centrifugation at 9500 g for 2 min, the supernatant was discarded and another 100 µl of PBST was added. The gel was thus washed three times with PBST between steps and the volume of fluid phase reagent was 100 µl in each step. The free active sites were blocked with 0·1 mol/l PBST containing 1% bovine serum albumin (PBST/BSA, Boehringer Ingelheim, Ridgefield, CT, USA) at 37°C for 1 h. Then biotinylated PNA and VVL diluted 1 : 200 in PBST/BSA was added to each tube, incubated for 1 h at 37°C and washed. The tubes were incubated with avidin–horseradish peroxidase (avidin–HRP, Sigma) diluted 1 : 20 000 in PBST/BSA for 40 min and then washed. An enzyme substrate consisting of 0·04%o-phenylenediamine dihydrochloride in 0·1 mol/l citrate phosphate buffer (pH 5·0) and 0·1% H2O2 (v/v) was used to reveal the results. The reaction was stopped with 1 mol/l H2SO4. Absorbance was read at 490 nm with a microplate reader (Biorad550, Bio-Rad, Tokyo, Japan). The assay was repeated five times and the absorbances were expressed as mean ± s.d.

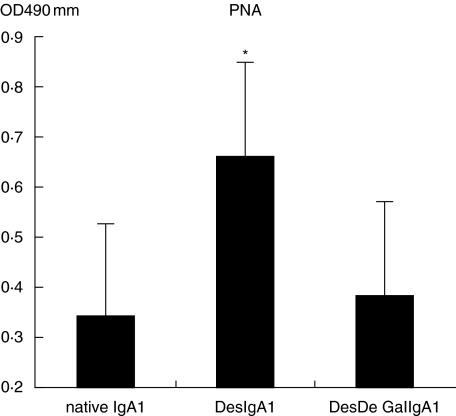

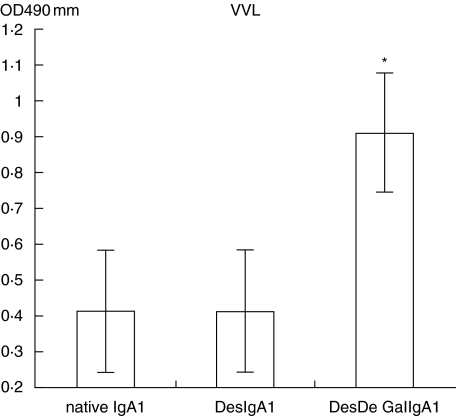

As shown in Figs 1 and 2, the IgA1 immobilized on Sepharose 4B proved to be deglycosylated efficiently by comparison of the relative levels of PNA and VVL in each column with Student's t-test.

Fig. 1.

Native IgA1 was desialylated efficiently through digestion with neuraminidase (DesIgA1/Sepharose versus IgA1/Sepharose and DesIgA1/Sepharose versus DesDeGalIgA1/Sepharose, P < 0·05).

Fig. 2.

Native IgA1 was degalactosylated efficiently through digestion with neuraminidase and β-galactosidase (DesDeGalIgA1/Sepharose versus IgA1/Sepharose and DesDeGalIgA1/Sepharose versus DesIgA1/Sepharose, P = 0·001).

Preparation of specific binding proteins from human sera towards DesIgA1/Sepharose and DesDeGalIgA1/Sepharose

Sera (0·5 ml) from patients with different pathological phenotypes of IgAN and healthy blood donors were applied to both DesIgA1/Sepharose and DesDeGalIgA1/Sepharose columns, respectively. The columns were washed with 0·1 mol/l Tri-HCl (pH 7·5). The binding proteins were then eluted thoroughly with 0·1 mol/l Tri-HCl containing 1 mol/l NaCl (pH 7·5). The eluted materials were concentrated with PEG 20 000, dialysed against 0·01 mol/l PBS overnight at 4°C and stored at −20°C. The total protein content of each IgA1 binding protein (IgA1-BP) was measured using a spectrophotometer under 260 nm and 280 nm.

Detection of IgA1 and glycans of IgA1 in IgA1-BP by sandwich-ELISA

The assay was performed as described previously [22]. Briefly, rabbit anti-human IgA (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark), diluted to 5·5 µg/ml in 0·05 mol/l bicarbonate buffer (pH 9·6), was coated to the wells on one-half of a polystyrene microtitre plate (Costar, Cambridge, MA, USA). The wells in the other half were coated with bicarbonate buffer alone to act as antigen-free wells. The volume of liquid reagents in every step was 100 µl. All incubations were carried out at 37°C for 1 h, and the plate was washed three times with PBST. The plate was then blocked with 1% PBST/BSA and the test samples were added in duplicate to both antigen-coated and antigen-free wells. For detection of IgA1 and α2,6 sialic acid, the samples were diluted to a dilution equivalent to 1 : 100 of original sera, and diluted to the equivalent of 1 : 40 of the original sera for detection of β1,3-Gal and terminal GalNAc. Purified IgA1, obtained from normal human sera through jacalin affinity chromatography, was diluted to 10 µg/ml and used as a positive control for the detection of IgA1 and α2,6-sialic acid. For detection of β1,3-Gal and terminal GalNAc, desialylated IgA1 (DesIgA1) and desialylated/degalactosylated IgA1 (DesDeGalIgA1) diluted to 10 µg/ml were used as positive controls. The biotinylated second antibody or lectins in PBST/BSA were then added, including 1 : 20 000 diluted monoclonal anti-human IgA1 (clone no. A1-18, Sigma) to detect the concentration of IgA1; 1 : 400 diluted elderberry bark lectin (SNA, Vector, USA) to detect α2,6-sialic acid; 1 : 50 diluted PNA to detect β1,3-Gal; and 1 : 200 diluted VVL to detect terminal GalNAc. The wells were then incubated with avidin–HRP diluted to 1 : 20 000 for 40 min. The results were revealed with the substrate as described above. The reaction was stopped with 1 mol/l H2SO4. Absorbance at 490 nm (A) was recorded by the microplate reader.

The relative concentration of IgA1 in IgA1-BP and the level of glycans were calculated as follows: the A value of the blank control was regarded as 0 and the A value of the known positive control was regarded as 100%. The A value of each sample was calculated by log-transformed data. The relative lectin binding per unit IgA1 was calculated as the A value of lectin over the A value of IgA1 concentration: level of glycans = A value of lectin/A value of IgA1 concentration.

Detection of IgG in IgA1-BP by sandwich-ELISA

Monoclonal anti-human IgG (clone no. GG-5, Sigma), diluted to 1 : 10 000 in the coating buffer as mentioned above, was coated to the wells of one-half of a microtitre plate, and the other half was coated with coating buffer alone as antigen-free wells. The plate was incubated at 37°C for 1 h. Purified IgG diluted from 3·13 µg/ml to 0·049 µg/ml were used as positive controls or standards. One hundred µl of reagents was added to the wells at every step and the plate was incubated at 37°C for 30 min between subsequent steps. Between steps the plate was washed three times with PBST. IgA1-BPs diluted to an equivalent of 1 : 80 of original sera were added in duplicate to both antigen-coated wells and antigen-free wells. After incubation, horseradish–peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-human IgG (ZhongShan Biotech, Beijing, China) diluted to 1 : 10000 was used as second antibody. The subsequent procedures were the same as described above and absorbance was recorded at 490 nm. The amount of IgG of each IgA1-BP was calculated.

Statistical analysis

For statistical analysis, statistical software spss version 11·0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA) was employed. Quantitative data were expressed as mean ± s.d. For comparison between patients and controls, Student's t-test and one-way analysis of variance (anova) test were used. A P-value of less than 0·05 was considered significant.

Results

Amount of IgA1-BP obtained from DesIgA1/Sepharose and DesDeGalIgA1/Sepharose.

As shown in Table 1, the total amounts of IgA1-BP obtained from both columns showed no significant difference between patients with different pathological phenotypes of IgAN and normal controls (P > 0·05).

Table 1.

The amount of IgA1-BP eluted from DesDeGalIgA1/Sepharose and DesIgA1/Sepharose.

| DesIgA1/Sepharose | DesDeGalIgA1/Sepharose | |

|---|---|---|

| NC | 0·52 ± 0·12 | 0·61 ± 0·15 |

| mIgAN | 0·59 ± 0·07 | 0·60 ± 0·09 |

| psIgAN | 0·54 ± 0·07 | 0·70 ± 0·21 |

| P | n.s. | n.s. |

n.s.: Not significant; mIgAN: mild mesangial proliferative IgA nephropathy (IgAN); psIgAN: proliferative sclerosing IgAN.

Amount of IgA1 in IgA1-BP obtained from DesIgA1/Sepharose and DesDeGalIgA1/Sepharose

In IgA1-BP eluted from DesIgA1/Sepharose, the amounts of IgA1 obtained from patients with mIgAN and from patients with psIgAN were much greater than from normal controls (mIgAN versus NC, 0·43 ± 0·15 mg versus 0·28 ± 0·19 mg, P = 0·035; psIgAN versus NC, 0·47 ± 0·12 mg versus 0·28 ± 0·19 mg, P = 0·009). There was no significant difference between patients with two pathological phenotypes of IgAN (mIgAN versus psIgAN, 0·42 ± 0·15 mg versus 0·47 ± 0·12 mg, P = 0·556) (see Table 2).

Table 2.

The amount of IgA1 in IgA1-BP eluted from DesIgA1/Sepharose and DesDeGalIgA1/Sepharose.

| DesIgA1/Sepharose | DesDeGalIgA1/Sepharose | |

|---|---|---|

| NC | 0·28 ± 0·19 | 0·29 ± 0·10 |

| mIgAN | 0·43 ± 0·15* | 0·40 ± 0·12* |

| psIgAN | 0·47 ± 0·12** | 0·44 ± 0·12** |

mIgAN: mild mesangial proliferative IgA nephropathy (IgAN); psIgAN: proliferative sclerosing IgAN.

mIgAN versus normal controls (NC), P < 0·05;

psIgAN versus NC, P < 0·05.

In IgA1-BP eluted from DesDeGalIgA1/Sepharose, the amounts of IgA1 obtained from patients with mIgAN and from patients with psIgAN were much greater than from normal controls (mIgAN versus NC, 0·40 ± 0·12 mg versus 0·29 ± 0·10 mg, P = 0·041; psIgAN versus NC, 0·44 ± 0·12 mg versus 0·29 ± 0·10 mg, P = 0·007). Significant differences could not be found between two groups of patients with IgAN (mIgAN versus psIgAN, 0·40 ± 0·12 mg versus 0·44 ± 0·12 mg, P = 0·435) (see Table 2).

Glycosylation of IgA1 in IgA1-BP obtained from DesIgA1/Sepharose and DesDeGalIgA1/Sepharose

In IgA1-BP eluted from DesIgA1/Sepharose, the relative levels of α2,6 sialic acid and β1,3-Gal of IgA1 in IgA1-BP were comparable between patients with both pathological phenotypes and normal controls (P > 0·05) (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Deglycosylation of IgA1 in IgA1-BP eluted from DesIgA1/Sepharose and DesDeGalIgA1/Sepharose.

| DesIgA1/Sepharose | DesDeGalIgA1/Sepharose | |

|---|---|---|

| α2,6-sialic acid | ||

| NC | 0·17 ± 0·33 | 0·24 ± 0·48 |

| mIgAN | 0·17 ± 0·28 | 0·24 ± 0·27 |

| psIgAN | 0·16 ± 0·28 | 0·22 ± 0·37 |

| β1,3-galactose | ||

| NC | 1·22 ± 0·68 | 1·19 ± 0·21 |

| mIgAN | 1·25 ± 0·42 | 0·86 ± 0·31* |

| psIgAN | 0·78 ± 0·34 | 0·78 ± 0·20** |

| GalNAc | ||

| NC | 0·042 ± 0·047 | 0·030 ± 0·024 |

| mIgAN | 0·065 ± 0·034 | 0·049 ± 0·041 |

| psIgAN | 0·060 ± 0·035 | 0·060 ± 0·031** |

mIgAN: mild mesangial proliferative IgA nephropathy (IgAN); psIgAN: proliferative sclerosing IgAN.

mIgAN versus normal controls (NC), P < 0·05;

psIgAN versus NC, P < 0·05.

In IgA1-BP eluted from DesDeGalIgA1/Sepharose, the relative levels of α2,6 sialic acid of IgA1 in IgA1-BP obtained from normal controls, patients with mIgAN and patients with psIgAN were 0·24 ± 0·48, 0·24 ± 0·27 and 0·22 ± 0·37, respectively and was comparable between groups (P > 0·05). The relative level of β1,3-Gal exposure of IgA1 was much lower in patients with both pathological phenotypes of IgAN than in normal controls (mIgAN versus NC, 0·86 ± 0·31 versus 1·19 ± 0·21, P = 0·005; psIgAN versus NC, 0·78 ± 0·20 versus 1·19 ± 0·21, P = 0·001). There was no significant difference between two groups of patients with IgAN (mIgAN psIgAN, 0·86 ± 0·31 versus 0·78 ± 0·20, P > 0·05). Exposure of GalNAc was much greater in patients with focal proliferative sclerosing IgAN than in normal controls (0·060 ± 0·031 versus 0·030 ± 0·024, P = 0·043). There was no significant difference between patients with mIgAN and normal controls (P > 0·05) (see Table 3).

Amount of IgG in IgA1-BP obtained from DesIgA1/Sepharose and DesDeGalIgA1/Sepharose

In IgA1-BP eluted from DesIgA/Sepharose, the amount of IgG had no significant difference in patients with both pathological phenotypes of IgAN and normal controls (P > 0·05) (see Table 4).

Table 4.

The amount of IgG in IgA1-BP eluted from DesIgA1/Sepharose and DesDeGalIgA1/Sepharose.

| DesIgA1/Sepharose | DesDeGalIgA1/Sepharose | |

|---|---|---|

| NC | 0·023 ± 0·009 | 0·033 ± 0·013 |

| mIgAN | 0·026 ± 0·003 | 0·046 ± 0·031 |

| psIgAN | 0·027 ± 0·002 | 0·064 ± 0·031* |

mIgAN: mild mesangial proliferative IgA nephropathy (IgAN); psIgAN: proliferative sclerosing IgAN.

psIgAN versus normal controls (NC), P < 0·05.

In IgA1-BP eluted from DesDeGalIgA1/Sepharose, the amount of IgG obtained from patients with psIgAN was much greater than from normal controls (0·064 ± 0·031 mg versus 0·033 ± 0·013 mg, P = 0·014), while there was no significant difference between patients with mIgAN and normal controls (0·046 ± 0·031 mg versus 0·033 ± 0·013 mg, P = 0·273) (see Table 4).

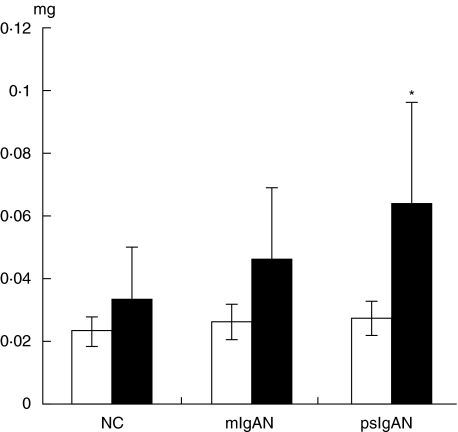

As shown in Fig. 3, only in patients with psIgAN was the amount of IgG eluted from DesDeGalIgA1/Sepharose significantly higher than from DesIgA1/Sepharose (0·064 ± 0·031 mg versus 0·027 ± 0·002 mg, P = 0·004). The difference could not be found in patients with mIgAN and normal controls.

Fig. 3.

Comparison of the amount of IgG in IgA1 binding proteins (IgA1-BP) obtained from DesIgA1/Sepharose and DesDeGalIgA1/Sepharose in each group. In patients with focal proliferative sclerosing IgA nephropathy (IgAN), the amount of IgG eluted from DesDeGalIgA1/Sepharose was much greater than that eluted from DesIgA1/Sepharose (0·064 ± 0·031 mg versus 0·027 ± 0·002 mg, P = 0·004). There were no significant differences between the amounts of IgG obtained from both columns in patients with mild mesangial proliferative IgAN and normal controls (P > 0·05). □, DesIgA1/Sepharose; ▪, DesDeGal1gA1/Sepharose.

Discussion

IgA nephropathy is characterized by the prevalent mesangial deposition of IgA, especially the IgA1 subclass, along with other immunoglobulins and complements. In contrast to other immunoglobulins, human IgA displays unique heterogeneity in its molecular form. Almost all circulating IgA is produced in the bone marrow [23]; it consists of monomeric IgA (mIgA), dimeric IgA (dIgA) and polymeric IgA (pIgA). The precise composition of pIgA is still unknown. These macromolecular IgA complexes might be aggregates of IgA, IgA-containing immune complexes or complexes of IgA associated with other proteins [24].

Although elevation of the circulating macromolecular IgA1 was found in approximately half the patients with IgAN, elevated levels of IgA1 and/or IgA1-containing complexes alone are not sufficient to cause the mesangial deposition of IgA1. This is witnessed by the rare occurrence of IgAN in patients with IgA1 myeloma or infection with HIV, which are also characterized by high circulating IgA1 or IgA1-containing complexes [25]. Therefore, it was speculated that the composition and characteristics of macromolecular IgA1 might play an important role in the pathogenesis of IgAN. In contrast to native IgA1, deglycosylated IgA1 and especially degalactosylated IgA1 had the potential to form complexes with more serum proteins [12,13,26]. In the sera of patients with IgAN, the amount of IgA1 binding to DesDeGalIgA1 was greater than that in the sera of patients with non-IgAN [27]. The glycosylation of IgA1 in IgA1-BP and their relationship with pathological phenotypes of the disease were not investigated further.

In the current study, although the amount of IgA1-BP eluted from DesIgA1/Sepharose and DesDeGalIgA1/Sepharose showed no significant difference between patients with IgAN and normal controls, the amount of IgA1 eluted from both columns was much higher in patients with IgAN than in normal controls, which coincided well with the reports of Nakamura et al. [27]. Furthermore, the amounts of IgA1 binding to DesIgA1/Sepharose and DesDeGalIgA1/Sepharose in patients with mild mesangial proliferative IgAN and focal proliferative sclerosing IgAN were both significantly higher than in normal controls. When glycosylation of IgA1 in IgA1-BP was detected, there was no difference for the glycosylation of IgA1 obtained from DesIgA1/Sepharose between patients with both pathological phenotypes and normal controls. For IgA1 of IgA1-BP eluted from DesDeGalIgA1/Sepharose, the loss of sialic acid was much more severe in patients with the two pathological phenotypes than in normal controls and, more importantly, degalactosylation was much more pronounced in patients with psIgAN than in normal controls. This proved further the fact that the level of macromolecular IgA1 has no association with the progression of IgAN, but deglycosylation of macromolecular IgA1 might be a contributory factor for the heterogeneity of development of the disease. It is known that the sialic acids are large and bulky, and carry a negative charge. Any change in the carbohydrate moieties affects the tertiary structure as well as the electrostatic charges. The loss of stability of IgA1 molecule might lead to the aggregation of IgA1 [5] and the deficiency of galactose might escape clearance by the liver [12,13]. It has been reported that the removal of sialic acid and Gal residues from IgA1 molecules could result in a significant increase in complement-binding properties [9], and GalNAc and Gal exposing glycoforms isolated from patients with IgAN were significantly more active for complement activation than were controls [28]. One recent study demonstrated that the aberrantly glycosylated IgA1-containing complex could affect the proliferation of mesangial cells in vitro and probably plays a role in the pathogenesis of IgAN [29].

Studies have shown that deglycosylated IgA1 molecules have an increased tendency to form self-aggregates or IgA1-containing complexes with IgG [12,13,26]. In the current study, more IgG bound to DesDeGalIgA1/Sepharose than to DesIgA1/Sepharose. The amount of IgG binding to DesDeGalIgA1/Sepharose was significantly higher in patients with psIgAN than in normal controls. These coincided well with reports that degalactosylated IgA1 could bind to IgG to form macromolecular IgA1 more easily [12]. Furthermore, when comparing the amount of IgG among patients with both pathological phenotypes and normal controls, the level of macromolecular complex composed of degalactosylated IgA1 and IgG was associated with the pathological phenotype of the disease. These deglycosylated macromolecular IgA1 complexes could reduce the rate of elimination and catabolic degradation by the liver and have a higher affinity to glomerular mesangial cells than uncomplexed IgA1 [12,13,30]. They undergo preferential deposition in the mesangial area by virtue of enhanced carbohydrate interactions with fibronectin, laminin and collagen of mesangial matrix [11]. There is also evidence that activation of the mesangial cells by co-deposited IgG could contribute synergistically to the development of a proinflammatory mesangial cell phenotype and thereby influence the degree of glomerular injury [31]. A previous study has reported that the binding of IgG in IgA1-BP was dissociated easily by a buffer with high salt concentration, but when eluted with an acid buffer (pH 3·0) no more additional IgA1-BP was eluted [26]. It was speculated that the binding of IgG to deglycosylated IgA1 might be related to a mechanism of self-aggregation of deglycosylated IgA1 and IgG but not to an antigen–antibody reaction.

Trace amounts of complement 3 (C3) were also found in IgA1-BP in a previous study [27]. In the current study, C3 was not detectable in IgA1-BP with the methods used to detect serum C3. However, we speculated that there might be an amount of complements, based on the fact that complements were among those co-deposited in the mesangial region with aggregated IgA1. Failure of the detection of C3 might be due to its trace amounts in IgA1-BP, and a more sophisticated method should be employed to measure C3 in IgA1-BP in future studies.

In summary, the current study confirmed further the important role that deglycosylated IgA1, and especially degalactosylated IgA1, might play in the pathogenesis of IgAN, and deglycosylated IgA1 had a higher affinity to other serum proteins than native ones. More importantly, in the current study we have demonstrated that deglycosylated IgA1 might have a tendency to aggregate with itself or with IgG to form macromolecular complexes, and they could be associated with the development of IgAN.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (30570852) and the Ministry of Health, People's Republic of China (2004230003).

References

- 1.Donadio JV, Joseph P. IgA nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:738–48. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra020109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li LS, Liu ZH. Epidemiologic data of renal diseases from a single unit in China: analysis based on 13 519 renal biopsies. Kidney Int. 2004;66:920–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00837.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang Y, Zhao MH, Zhang YK, Li XM, Wang HY. Binding capacity and pathophysiological effects of IgA1 from patients with IgA nephropathy on human glomerular mesangial cells. Clin Exp Immunol. 2004;136:168–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2004.02408.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang Y, Zhao MH, Li XM, Zhang YK, Wang HY. Serum IgA1 from patients with IgA nephropathy induces phosphorylation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase and proliferation of human mesangial cells. Zhonghua-Yi-Xue-Za-Zhi. 2002;82:1406–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kerr MA. The structure and function of IgA. Biochem J. 1990;271:285–96. doi: 10.1042/bj2710285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Allen AC, Bailey EM, Brenchley PE, Buck KS, Barratt J. Mesangial IgA1 in IgA nephropathy exhibits aberrant O-glycosylation: observations in three patients. Kidney Int. 2001;60:969–73. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.060003969.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Takatani T, Iwase H, Itoh A, et al. Compositional similarity between immunoglobulins binding to asialo-, agalacto-IgA1-Sepharose and those deposited in glomeruli in IgA nephropathy. J Nephrol. 2004;17:679–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ogawa Y, Ishizu A, Ishidura H, Yoshiki T. Elution of IgA from kidney tissues exhibiting glomerular IgA deposition and analysis of antibody specificity. Pathobiology. 2002–03;70:98–102. doi: 10.1159/000067309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hiki Y, Kokubo T, Iwase H, et al. Underglycosylation of IgA1 hinge plays a certain role for its glomerular deposition in IgA nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1999;10:760–9. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V104760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sano T, Hiki Y, Kokubo T, et al. Enzymatically deglycosylated human IgA1 molecules accumulate and induce inflammatory cell reaction in rat glomeruli. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2002;17:50–6. doi: 10.1093/ndt/17.1.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kokubo T, Hiki Y, Iwase H, et al. Protective role of IgA1 glycans against IgA1 self-aggregation and adhesion to extracellular matrix proteins. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1998;9:2048–54. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V9112048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tomana M, Matousovic K, Jullian BA, Radl J, Konecny K, Mestecky J. Galactose-deficient IgA1 in sera of IgA nephropathy patients is present in complexes with IgG. Kidney Int. 1997;52:509–16. doi: 10.1038/ki.1997.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tomana M, Novak J, Jullian BA, Matousovic K, Konecny K, Mestecky J. Circulating immune complexes in IgA nephropathy consist of IgA1 with galactose-deficient hinge region and antiglycan antibodies. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:73–81. doi: 10.1172/JCI5535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang JJ, Xu LX, Zhang Y, Zhao MH. Binding capacity of in vitro declycosylated IgA1 to human mesangial cells. Clin Immunol. 2006. Jan 24; [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Hiki Y, Odani H, Takahashi M, et al. Mass spectrometry proves under-O-glycosylation of glomerular IgA1 in IgA nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2001;59:1077–85. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.0590031077.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coppo R, Amore A. Aberrant glycosylation in IgA nephropathy (IgAN) Kidney Int. 2004;65:1544–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.05407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xu LX, Zhao MH. Aberrantly glycosylated serum IgA1 is closely associated with pathological phenotypes of IgA nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2005;68:167–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00390.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harper SJ, Feehally J. The pathogenic role of immunoglobulin A polymers in immunoglobulin A nephropathy. Nephron. 1993;65:337–45. doi: 10.1159/000187509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van der Boog PJ, van Kooten C, van Seggelen A, et al. An increased polymeric IgA level is not a prognostic marker for progressive IgA nephropathy. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2004;19:2487–93. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfh394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haas M. Histologic subclassification of IgA nephropathy: a clinicopathologic study of 244 cases. Am J Kidney Dis. 1997;29:829–42. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(97)90456-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Diven SC, Caflisch CR, Hammond DK, Weigel PH, Oka JA, Goldblum RM. IgA induced activation of human mesangial cells: independent of Fcar1 (CD 89) Kidney Int. 1998;54:837–47. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1998.00054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Allen AC, Harper SJ, Feehally J. Galactosylation of N- and O-linked carbohydrate moieties of IgA1 and IgG in IgA nephropathy. Clin Exp Immunol. 1995;100:470–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1995.tb03724.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van den Wall Bake AW, Daha MR, Haaijman JJ, Radl J, van der Ark A, van Es LA. Elevated production of polymeric and monomeric IgA1 by the bone marrow in IgA nephropathy. Kidney Int. 1989;35:1400–4. doi: 10.1038/ki.1989.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van der Boog PJ, van Kooten C, de Fijter JW, Daha MR. Role of macromolecular IgA in IgA nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2005;67:813–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00146.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van den Wall Bake AW, Kirk KA, Gay RE, et al. Binding of serum immunoglobulins to collagens in IgA nephropathy and HIV infection. Kidney Int. 1992;42:374–82. doi: 10.1038/ki.1992.298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Iwase H, Yokozeki Y, Hiki Y, et al. Human serum immunoglobulin G3 subclass bound preferentially to asialo-, agalactoimmunoglobulin A1/Sepharose. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;264:424–9. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nakamura I, Iwase H, Ohba Y, Hiki Y, Katsumat T, Kobayashi Y. Quantitative analysis of IgA1 binding protein prepared from human serum by hypoglycosylated IgA1/Sepharose affinity chromatography. J Chromatogr B. 2002;776:101–6. doi: 10.1016/s1570-0232(02)00176-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Amore A, Coppo R. Modulation of mesangial cell reactivity by aberrantly glycosylated IgA. Nephron. 2000;86:255–9. doi: 10.1159/000045778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Novak J, Tomana M, Matousovic K, et al. IgA1-containing immune complexes in IgA nephropathy differentially affect proliferation of mesangial cells. Kidney Int. 2005;67:504–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.67107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Novak J, Vu HL, Novak L, Julian BA, Mestecky J, Tomana M. Interactions of human mesangial cells with IgA and IgA-containing immune complexes. Kidney Int. 2002;62:465–75. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00477.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van Dixhoom MG, Sato T, Muizert Y, van Gijlswijk-Janssen DJ, De Heer E, Dah MR. Combined glomerular deposition of polymeric rat IgA and IgG aggravates renal inflammation. Kidney Int. 2000;58:90–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00144.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]