Abstract

Transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) and prostaglandins (PG) regulate the cell-mediated immune response, so it has been proposed that they affect the progression of pulmonary tuberculosis. Here we report that the administration of soluble betaglycan, a potent TGF-β antagonist, and niflumic acid, a PG synthesis inhibitor, during the chronic phase of experimental murine tuberculosis enhanced Th1 and decreased Th2 cytokines, increased the expression of iNOS and reduced pulmonary inflammation, fibrosis and bacillary load. This immunotherapeutic approach resulted in significant control of the disease comparable to that achieved by anti-microbial treatment alone. Importantly, the combination of immunotherapy and anti-microbials resulted in an accelerated clearance of bacilli from the lung. These results confirm that TGF-β and PG have a central pathophysiological role in the progression of pulmonary tuberculosis in the mouse and suggest that the addition of immunotherapy to conventional anti-microbial drugs might result in improved treatment of the disease.

Keywords: cell-mediated immune response, immunotherapy, prostaglandins, TGF-β, tuberculosis

Introduction

Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection is still a major world health problem. Eradication will require the sustained action of physicians, medical scientists and governments. The long (6-month) chemotherapy regimens are a major hurdle which, together with the appearance of drug-resistant strains of bacilli, limit the success of treatment [1]. In principle, improvement of the host immune response by vaccination or immunotherapy could help to alleviate the shortcomings of the antibiotics [2–4]. Work conducted in vitro, as well as with an experimental murine model that resembles closely human pulmonary tuberculosis, particularly in developing countries where there are high challenging doses and a tendency for elevated Th-2 response in progressive disease [5], has suggested that transforming growth factor (TGF)-β and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), which decrease the cell-mediated immune response (CMI), are significant mediators of tuberculosis progression [6–8].

Mycobacterial infections are controlled by activation of macrophages through type I cytokine production by T cells [9–11]. Interferon (IFN)-γ and tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α are essential for this process, as they promote macrophage activation and the expression of the inducible form of nitric oxide synthase (iNOS). In most murine models, iNOS is essential for the killing of intracellular mycobacteria [12]. Suppression of T cell responses to mycobacterial antigens in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) is a consistent feature of tuberculosis [13], and in vitro observations indicate that TGF-β participates in these effects [8,14,15]. TGF-β supresses the CMI at multiple levels [16]. It blocks lymphocyte proliferation and function (CD-4 cells are particularly susceptible), suppresses interleukin (IL)-2 production, suppresses expression of the IFN-γ receptor and of major histocompatibility complex (MHC)-II [17–19] and blocks IFN-γ-induced macrophage activation [20], causing inhibition of IL-1, TNF-α and iNOS production [21,22]. Similarly, the high PGE2 concentrations present during the late phase of the murine disease contribute to increased pneumonia and to decreased expression of IFN-γ, TNF-α and iNOS [7]. Additionally TGF-β is capable of inducing collagen synthesis and promoting fibrosis, a common abnormality in advanced pulmonary tuberculosis [23]. In order to determine the pathophysiological relevance of TGF-β and PGE2 we have treated pulmonary tuberculosis in mice with TGF-β-neutralizing agents and cyclooxyenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitors which decrease the production of PGE2. Our findings indicate that during the late phase of the disease this therapeutic regimen reduced bacterial load to an extent similar to that achieved by conventional anti-microbial treatment. Our results confirm that TGF-β and PGE2 are major mediators of the defective cellular immune response that leads to the progression of tuberculosis. Furthermore, they suggest that combining anti-microbial and immunotherapeutic approaches might attain optimal treatment of human tuberculosis.

Materials and methods

Experimental model of progressive pulmonary tuberculosis

The experimental model of pulmonary tuberculosis has been described previously in detail [6,24]. Briefly, male BALB/c mice from 6 to 8 weeks of age were used. The virulent M. tuberculosis strain H37Rv was cultured in Proskauer and Beck medium modified by Youmans. After 1 month of culture, bacilli were harvested and resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at 107 live cells/ml. Bacilli were stored in 100 µl aliquots at −70°C and their viability was checked before use [24]. To induce pulmonary tuberculosis, mice were anaesthetized with 56 mg/kg of intraperitoneal pentothal (Anestesal, Smith Kline, Mexico City, Mexico). The trachea was exposed via a small midline incision, and 2·5 × 105 viable bacteria were instilled. The incision was sutured with sterile silk, and the mice were maintained in a vertical position until the effect of anaesthesia passed. Infected mice were maintained in cages fitted with micro insulators connected to negative pressure. Two experiments were performed, and the data pooled. All procedures were performed in a laminar flow cabinet in bio-safety level III facilities. The protocol was approved by the Ethical Committee for Experimentation in Animals of the National Institute of Medical Sciences and Nutrition in Mexico.

Pharmacological management during the late phase of the infection

We have shown previously that in this experimental model TGF-β is produced in low concentrations during the early phase of the disease (first month post-infection), increasing to a stable high level during the late phase of the infection [6]. Therefore, in order to block TGF-β during the late phase, we employed recombinant soluble betaglycan (SBG) or commercially available pan-specific TGF-β neutralizing antibodies (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MI, USA). SBG was produced in insect cells using the baculoviral expression system from a suitably modified cDNA as a secretory protein that corresponds to the extracellular region of betaglycan, also known as the type III TGF-β receptor [25]. This protein resembles the soluble form of betaglycan which, similar to its membrane counterpart, exhibits high binding affinities for all TGF-β isoforms, but in contrast to the membrane form prevents their binding to the signalling types I and II TGF-β receptors. Therefore it functions as a TGF-β neutralizing agent [25]. Initially, we determined an optimal SBG dose to block TGF-β activity, taking colony-forming unit (CFU) determinations in lung homogenates and delayed-type hypersensitivity (DTH) responses as evaluation parameters. We found that 30 µg administered twice per week by the intraperitoneal route was optimal. Thus, we performed two independent experiments with this dose of SBG starting the treatment at day 30 post-infection, when the late phase of the infection begins and the TGF-β concentration is raised and maintained at a high level. For comparison purposes, another group of chronically infected mice was treated on alternate days with 20 µg intraperitoneally (i.p.) of anti-TGF-β pan-specific blocking antibodies (R&D Systems). In terms of their in vitro TGF-β1 neutralizing activity these doses of SBG and antibody are equivalent [25], and are predicted to neutralize fully the TGF-β1 concentration found in the lungs of the mice subjected to this experimental form of pulmonary tuberculosis [6]. In the experiments in which niflumic acid (NA) was included, 500 µg was administered twice per day using intragastric canulation. For the first set of experiments there were three groups of mice. Group one received SBG, group two was treated with blocking pan-specific TGF-β antibodies, and group three received SBG plus NA. A control group received the diluent (saline solution) by gavage and the i.p. route. The anti-tuberculosis drugs used in the experiment shown in Fig. 5 (later) were: rifampicin 10 mg/kg, isoniazid 10 mg/kg and pyrazinamide 30 mg/kg. These were administered daily using intragastric cannulation.

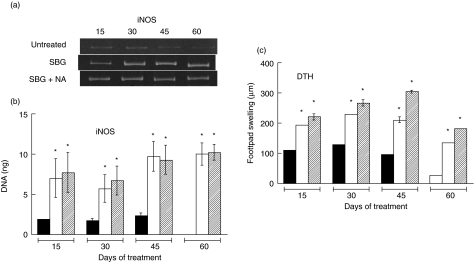

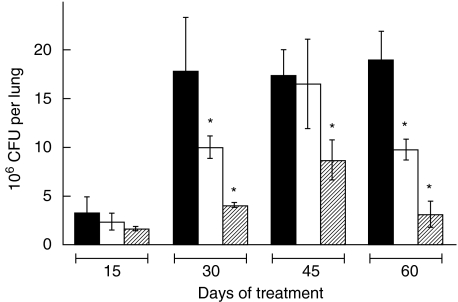

Fig. 5.

Lung colony-forming units (CFU) during anti-microbial and/or immunotherapy regimens. Mycobacterium tuberculosis CFU were determined as shown in Fig. 4 from the lungs of mice subjected to the following treatments: control untreated mice (c, black bars), soluble betaglycan (SBG) plus niflumic acid (NA) (i, cross-hatched bars), anti-microbial drugs (a, grey bars), SBG plus NA and anti-microbial drugs (i + a, double cross-hatched bars). Statistical analysis indicated a significant difference (P< 0·01) for the indicated treatments (*) when compared with their corresponding day of treatment controls. Additionally, the decrease of CFU obtained by the SBG plus NA plus anti-microbial treatment (¶) was significantly (P= 0·03) different when compared against the anti-microbial drugs alone at day 30 of treatment.

Pathology of infected lungs

After 15, 30, 45 and 60 days of the different treatments, groups of eight mice were killed by exsanguination. One lung, right or left, was perfused with absolute ethyl alcohol for histological analysis, and the other lung was frozen in liquid nitrogen for other determinations. Using an automated image analyser (Q Win Leica, Milton Keynes, UK), we determined the percentage of lung surface affected by pneumonia and the area of granuloma in the different groups [24]. In lung sections stained with Masson trichrome, we also determined by automated morphometry the percentage of lung surface affected by fibrosis.

Determination of CFU in infected lungs

Right or left lungs from four mice, in two different experiments per each killing time-interval, were used for M. tuberculosis colony counting. Lungs were homogenized with a Polytron (Kinematica, Lucerne, Switzerland) in sterile 50 ml tubes containing 3 ml of isotonic saline. Four dilutions of each homogenate were spread onto duplicate plates containing Bacto Middlebrook 7H10 agar (Difco Laboratory code 0627-17-4, Difco Laboratories, Detroit, MI, USA) enriched with oleic acid, albumine, catalase and dextrose enriched medium (OADC). The time for incubation and colony counting was 21 days [26].

Analysis of iNOS in lung homogenates by reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT–PCR)

Four lungs, right or left, were used to isolate RNA from the different mice groups at each killing time-point using Trizol (Gibco brl, Gaithersburgh, MD, USA), as described previously [6,24]. cDNA was synthesized by using Maloney murine leukaemia virus reverse transcriptase (Gibco brl) and oligo dT priming. The cDNA from four infected mice per sacrifice point was pooled. The expression of iNOS mRNA (and of other cytokines) was determined by RT–PCR, as described previously [6,24,27]. The PCR products were electrophoresed on 6% polyacrylamide gels, running molecular weight standards with known DNA mass and concentration (Gibco brl, low DNA mass ladder), and analysed with an image analysis densitometer coupled to a computer program (ID image analysis software, Kodak Digital Science, Rochester, NY, USA). To determine the approximate mRNA concentration of each cytokine in nanograms, the computer program compared the optical densities from the experimental samples with the molecular marker bands containing known quantities of DNA. Expression of glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase was used to control for RNA content and integrity.

Quantification of cytokines in lung homogenates by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

The lung homogenates used for RNA purification were also used to quantify cytokines by ELISA [26]. After homogenization and centrifugation, the protein phase was extensively dialysed in sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS) and quantified with Bradford reagent (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) using a standard curve with bovine serum albumin (BSA). To quantify IL-2, IL-4, IFN-γ and TNF-α capture ELISAs were performed using monoclonal antibody pairs and recombinant standards (Pharmingen, San Jose, CA, USA). Briefly, 96-well plates were coated with 0·5 µg/ml of monoclonal anti-mouse IL-2, IFN-γ, IL-4 or TNF-α dissolved in 100 µl of 0·05 M carbonate buffer, pH 9·5, overnight at 4°C. After washing with PBS-Tween 0·05%, wells were blocked with 1% BSA in PBS-Tween 20 for 2 h at room temperature. Lung homogenate protein at 0·5 µg/ml in 100 µl PBS was incubated for 3 h at 37°C. After washing, biotinylated polyclonal rabbit anti-mouse IL-2, IL-4, IFN-γ or TNF-α at 1 µg/ml in PBS-Tween were incubated with streptavidin peroxidase diluted 1/1000 in PBS/Tween for 1 h at room temperature. To reveal the peroxidase, orthophenylenediamine and H2O2 were used.

Measurement of cutaneous DTH

Culture filtrate was harvested by filtration from M. tuberculosis H37Rv grown as described above for 4–5 weeks. Then culture filtrate antigens were precipitated with 45% (w/v) ammonium sulphate, washed and redissolved in PBS. For DTH measurement, each mouse received an injection of 20 µg of antigen in 40 µl of PBS into the hind footpad. The footpad was measured with an engineer's micrometer before and 24 h after the antigen injection [27]. Each data point represents the means of eight mice, four from each time-point and experiment comparing the different groups.

Statistics

A one-way analysis of variance (anova) and Student's t-test were used to compare morphometry and CFU determinations in infected mice treated with TGF-β blockers and non-treated control animals. A difference of P < 0·05 was considered significant. The analysis of data in Fig. 1 was performed by a general linear model of contrasts [28].

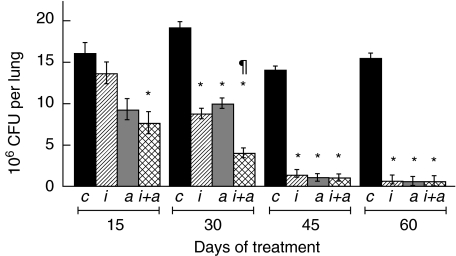

Fig. 1.

Histology and morphometry of lungs. Representative whole mounts of lungs from control untreated (a), soluble betaglycan (SBG) (b) and SBG plus niflumic acid (NA) (c) treated animals at the end of the experiment (60 days of treatment). Morphometry of lung area affected by pneumonia (d), granuloma size (e) and percentage of fibrotic lung surface (f), comparing control non-treated mice (black bars), animals treated with SBG (white bars) and with a combination of SBG plus NA (cross-hatched bars) at the indicated times of treatment. Data are means from eight mice in two different experiments and three random fields from each pulmonary lobe. Asterisk: statistical significance with respect to the control group (P< 0·05).

Results

Histopathological effects of blocking TGF-β during the late phase of tuberculosis infection

In order to inhibit TGF-β we have chosen recombinant soluble betaglycan (SBG), a potent anti-TGF-β agent with properties that make it ideal for long-term therapeutic use in animals and humans [25]. Preliminary studies indicate that the optimal dose of SBG was 30 µg intraperitoneally per animal twice a week. These same studies revealed that the degree of pneumonia was significantly higher in the SBG-treated than in the control untreated animals. Because TGF-β is a potent anti-inflammatory cytokine [29,30], we thought that its suppression might result in tissue damage due to excessive inflammation. Therefore, for the full-scale experiments at the optimal dose of SBG, we included another experimental group treated with SBG plus one efficient anti-inflammatory drug. We chose niflumic acid (NA), a drug that specifically blocks COX-2, the inducible and rate-limiting enzyme of PG synthesis.

Histological analysis of lungs after 60 days of treatment showed progressively increasing pneumonia, affecting the 45% of the lung surface of control untreated mice (Fig. 1a,d). Noticeably, recipients of SBG had 25% more pneumonia than the control mice after 2 months of treatment (Fig. 1b,d). Importantly, the intraperitoneal administration of a pan-specific TGF-β blocking antibody also led to increased pneumonia relative to the controls (not shown), indicating that this was an effect of blocking TGF-β and not a non-specific side effect of our recombinant protein. When NA was added to the SBG treatment the lung surface affected by pneumonia decreased significantly to only half of what was observed in control untreated mice after 2 months of treatment (Fig. 1c,d).

The area of granuloma in control untreated animals was lower than in mice treated with SBG or the combination SBG plus NA (Fig. 1e). Interestingly, the SBG-treated mice showed a significant decrease of lung surface affected by fibrosis in comparison with the controls (Fig. 1f). The fact that the same effect was observed in mice with the anti-TGF-β antibodies (not shown) suggests strongly that the fibrosis observed in the late phase of the infection is caused by the TGF-β. Similar fibrotic effects of TGF-β, its so-called ‘dark-side’, have been documented extensively in pathologies affecting organs such as kidney and liver [31].

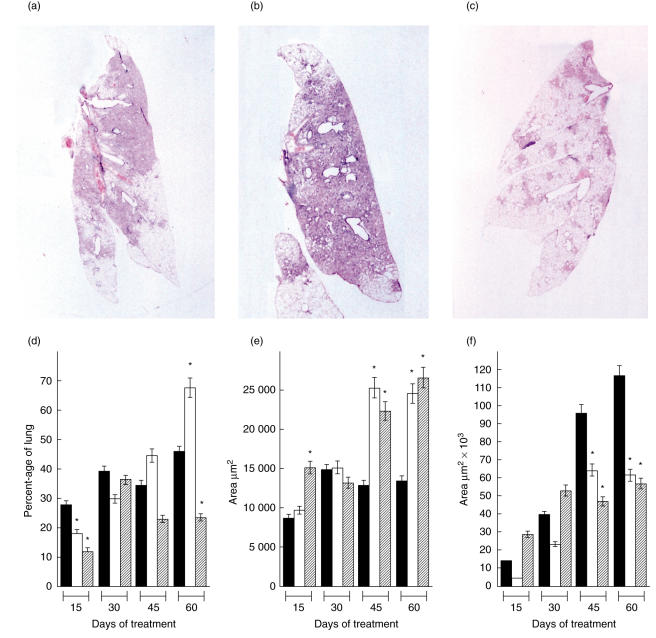

Effects of blocking TGF-β on Th1 and Th2 cytokines in the lung

Decreased Th1 and increased Th2 cytokines are characteristic features of the late progressive phase of our murine model of tuberculosis. In order to determine whether or not neutralization of TGF-β could reverse these effects we measured IFN-γ, IL-2, IL-4 and TNF-α by ELISA in lung homogenates of SBG-treated animals. IFN-γ and IL-2 were consistently higher in SBG-treated animals than in control untreated mice at the four time-points of the experiment (Fig. 2a,b). After 2 months of treatment the levels of these two Th1 cytokines were twofold higher in the SBG-treated group than in control untreated animals. At the same time, however, IL-4, a Th2 cytokine, was at only 30% of the level found in the control untreated group (Fig. 2c). Interestingly, combined treatment with SBG and NA did not exert a further effect on the balance of Th1–Th2 cytokines. The levels of TNF-α were higher in the SBG-treated animals than in the control animals at all the time-points. Addition of NA to the treatment further increased levels of TNF-α, especially after 45 and 60 days of treatment (Fig. 2d). Based on our recent findings that high lung concentrations of PGE2 during the late phase tuberculosis contribute to modulation of the cellular immune response [7], we expected that NA would synergize with all the effects of SBG on cytokine levels. None the less, our data indicate that this expectation was fulfilled significantly only for TNF-α. Importantly, when the same cytokines were studied by RT–PCR, the pattern observed was similar to that revealed by the ELISA, suggesting that TGF-β operates at the level of gene expression (not shown).

Fig. 2.

Lung cytokine levels during immunotherapy. Concentrations of the indicated cytokines, interferon (IFN)-γ (a), interleukin (IL)-2 (c), IL-4 (c) and tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α (d) were determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay using lung extracts of control untreated mice (black bars), animals treated with soluble betaglycan (SBG) (white bars) and animals treated with the combination of SBG plus niflumic acid (NA) (cross-hatched bars) at the indicated times of treatment. Data are means from eight mice in two different experiments. Asterisk: statistical significance with respect to the control group (P< 0·05).

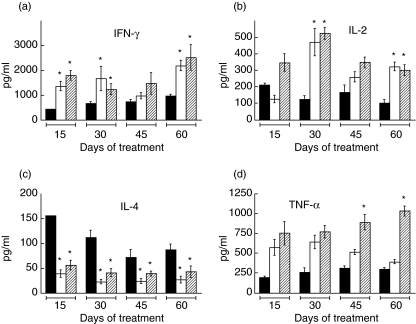

Effects of blocking TGF-β activity on iNOS and DTH responses

The sustained lung TNF-α levels in the presence of sustained Th1 and decreased Th2 cytokines suggested an enhanced cellular immune response and a better macrophage response against the bacilli. To assess these questions we measured the levels of lung iNOS mRNA by RT–PCR and the DTH responses to mycobacterial antigens in these mice. As shown in Fig. 3a,b the levels of iNOS mRNA were low in the untreated animals at all times, and by day 60 were practically undetectable. On the other hand, the animals treated with SBG, whether alone or together with NA, had higher levels of iNOS mRNA at every experimental time-point. Similarly, the DTH responsiveness declined progressively in the control untreated animals, while it was significantly greater in the SBG-treated animals. This increase was slightly higher in the animals given the combination of SBG plus NA (Fig. 3c).

Fig. 3.

Delayed-type hypersensitivity (DTH) and lung inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) mRNA during immunotherapy of tuberculosis. The relative amount of iNOS mRNA in lung extracts (a,b) and the DTH response (c) of control untreated mice (black bars), animals treated with soluble betaglycan (SBG) (white bars) and animals treated with a combination of SBG plus niflumic acid (NA) (cross-hatched bars) at the indicated times of treatment are shown. (a) Representative result from reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT–PCR) for iNOS mRNA. Loading control was determined separately by RT–PCR of GA3PDH mRNA (not shown). (b) Combined results from eight mice in two different experiments. (c) DTH responses to soluble antigens of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in tuberculous animals. Swelling was measured 24 h after challenge. Asterisk: statistical significance with respect to the control group (P< 0·05).

Effect of blocking TGF-β activity on counts of M. tuberculosis in the lung

As predicted from the above results, the burden of infection was dramatically decreased in the animals treated with SBG or SBG plus NA. CFU in the lungs of control untreated mice rose steadily, whereas they fell significantly after 30 days of treatment with SBG and SBG and NA (Fig. 4). After 60 days of treatment, mice treated with SBG showed 50% fewer CFU than controls, while those treated with the combination of SBG and NA showed the most striking decrease in CFU, which were sixfold less than the control mice.

Fig. 4.

Lung colony-forming units (CFU) during immunotherapy of tuberculosis. Mice were infected intratracheally with H37Rv Mycobacterium tuberculosis as described in Methods. One month post-infection the indicated treatments were initiated and continued for 2 months. CFU from the lungs were determined as described in Methods at the indicated treatment times. Control untreated mice (black bars), animals treated with soluble betaglycan (SBG) (white bars) and animals treated with a combination of SBG plus niflumic acid (NA) (cross-hatched bars) are shown. Asterisk: statistical significance (P< 0·05).

Comparison of anti-microbial therapy and anti-TGF-β-based immunotherapy

The above results indicate that an immunotherapeutic scheme based on the neutralization of TGF-β and PGE2 could limit successfully the progression of tuberculosis. Thus, in order to compare the efficiency of this regimen with the standard anti-microbial treatment, we set up another experiment including anti-microbial treatment groups (typical anti-tuberculosis drugs at the conventional doses). As a parameter of efficiency we measured the pulmonary CFU at different times of treatment. Figure 5 indicates that, as expected, the two groups receiving standard anti-microbial therapy showed decreasing CFU at every time-point, reaching an almost complete bacterial clearance after 2 months. Strikingly, the combination of SBG plus NA was as effective as standard anti-microbial therapy at 30, 45 and 60 days. These results indicate that the efficiency of the immunotherapeutic approach alone is comparable to that of the chemotherapeutic regimen. The combination of standard anti-microbial therapy plus SBG and NA was the treatment that produced the lowest CFU at every time-point of the experiment (Fig. 5). Importantly, this treatment achieved the fastest rate of clearance of bacilli at day 30, with CFU values that were significantly lower than those produced by the anti-microbial or immunotherapeutic schemes separately.

Discussion

In the late 1990s the work of Toossi and Ellner pointed to TGF-β as an important factor in the pathophysiology of tuberculosis. Their work with peripheral blood mononuclear cells from tuberculous patients demonstrated that their deficient T cell responses, INF-γ production and antigen-driven blastogenesis could be restored by TGF-β-neutralizing agents [14,15]. These observations prompted them to propose the possibility of using inhibitors of TGF-β as adjuvants to anti-tuberculous chemotherapy [8]. At the same time, our work with an experimental murine model that resembles human pulmonary tuberculosis supported this notion by showing a clear correlation between TGF-β levels and progression of the disease [6]. It is important to point out that this animal model resembles better the disease in developing countries, where there are high infecting doses and a marked tendency for elevated IL-4 responses in progressive disease [5]. Moreover, fibrosis in human tuberculosis might be related to the presence of the Th2-like response. It has been reported that pulmonary fibrosis in systemic sclerosis is associated with CD8 cells secreting IL-4 and IL-4δ2 [32], and in IL-4-null Balb/c mice the absence of IL-4 led to very low TGF-β production during the progressive phase of the disease, with lesser fibrosis and diminished bacterial growth [33]. All these findings confirm that Th-2 cytokines are directly involved in the development of fibrosis, probably by inducing TGF-β production [34]. In the present work, we study the participation of TGF-β in the induction of immunosuppression and fibrosis during experimental tuberculosis, and test for the first time the feasibility of manipulate this cytokine with therapeutic proposal.

It is well established that M. tuberculosis and its components are efficient inducers of TGF-β1 production by macrophages. TGF-β1, the best-studied of the three human TGF-β isoforms, is involved in suppression of the CMI and in the induction of fibrosis. Moreover, TGF-β is a key immunoregulatory cytokine produced by the recently characterized T regulatory cells population [35]. In tuberculosis, these activities are important considering that in mouse and humans, M. tuberculosis infection is controlled mainly by macrophage activation induced through Th1 cytokines, and extensive fibrosis is a common feature of this disease [4]. These abnormalities are observed in the lungs of BALB/c mice infected via the trachea with M. tuberculosis H37Rv [6,24]. In this model, there is an initial phase of partial resistance dominated by Th1 cytokines plus TNF-α and expression of the inducible form of nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), followed by a late phase of progressive disease characterized by a drop in the number of cells expressing IL-2, TNF-α or iNOS, progressive pneumonia, extensive interstitial fibrosis, high bacillary counts and very high levels of TGF-β. These high TGF-β levels, produced by infected macrophages and possibly also by regulatory T lymphocytes, are likely to contribute to the fibrosis and down-regulation of the CMI that permits disease progression.

Using this animal model we analysed the pathological and immunological effects of blocking TGF-β activity during the progressive phase of the disease. For that purpose SBG, a recombinant soluble receptor protein with a strong TGF-β neutralizing activity [25], was administrated during the second and third month post-infection, which corresponds to the late and progressive phase of the disease [6]. In comparison with control animals, the suppression of the TGF-β activity produced higher expression of TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-2, iNOS and lower expression of IL-4, together with significantly decreased lung fibrosis and bacillary load. However, there was also a significantly higher inflammatory response manifested as a greater area of lung affected by pneumonia. This side effect was not totally unexpected, in view of TGF-β's important anti-inflammatory activity [16, 29, 30]. In addition, it indicates that TGF-β plays multiple roles in the progression of pulmonary tuberculosis, first as down-regulator of CMI, secondly as a profibrogenic factor and thirdly as a suppressor of excessive inflammation. The latter role could be considered as a useful reaction preventing tissue damage in lungs with advanced tuberculosis; unfortunately, an excess of TGF-β contributes simultaneously to progressive deterioration of the protective immune response. Thus, in tuberculosis, as in other diseases in which TGF-β has a physiopathological contribution, this cytokine can play several, sometimes contrasting, roles [23]. In our murine model of tuberculosis the levels of TGF-β seem to determine whether an infected mouse develops a protective response or progressive disease and immunopathology. Too much TGF-β down-regulates Th1 responses allowing immunopathology and leading to susceptibility and progression, while too little TGF-β allows microbe expansion and persistent infection. Interestingly, a very similar two-faced role has been proposed for the TGF-β produced by regulatory T lymphocytes in other infectious diseases [35].

From the therapeutic perspective, blocking TGF-β produced a significant improvment in the protective immune response decreasing the lung bacillary loads, but at the same time too much inflammation with lung consolidation. In order to limit the proinflammatory side effect of the anti-TGF-β treatment, a group of animals in this late phase of the infection were treated with SBG plus the anti-inflammatory drug NA, a potent and specific inhibitor of cyclooxygenase 2, which is the rate-limiting enzyme for prostaglandin production. The choice of NA was also supported by our recent findings that high concentrations of PGE2 in lung during the late phase tuberculosis contribute to modulation of the cellular immune response [7]. Interestingly, the combination of SBG and NA produced a significant reduction in bacillary load and had a significant synergistic effect on the levels of pulmonary TNF-α. The fact that TNF-α was the only cytokine exhibiting this synergistic response suggests that its expression is regulated by both TGF-β and PG, and emphasized the proposal that it has a crucial protective role in the presence of a favourable high Th1 plus low Th2 context, as has been proposed before [36,37]. As important as the modulation of TNF-α may be, treatment with SBG plus NA also affected other cytokines and effectors, such as INF-γ, IL-2, IL-4 and iNOS, that are relevant in the progression of tuberculosis. This emphasized further that successful immunotherapeutic approaches against M. tuberculosis and other intracellular facultative infectious agents must be as immunoregulatory as possible [38].

In summary, our results demonstrate that TGF-β is a significant cytokine that is involved in the regulation of macrophage activation, Th1 and Th2 responses and of both protective and immunopathological mechanisms. These activities are susceptible to be therapeutically manipulated for the treatment of tuberculous animals. SBG, which blocks TGF-β, in combination with an anti-inflammatory drug, produced a synergistic effect in the elimination of bacilli and avoided excessive inflammation, constituting a novel immunotherapeutic regimen. Recent studies indicate that similar immunological disturbances may play an important pathophysiological role in the human disease. Therefore this novel treatment opens an unexplored avenue for treatment, especially in immunocompromised patients or in those infected with drug-resistant strains. Furthermore, our results also revealed that this immunotherapeutic regimen is, in terms of bacillary load in the lungs, as effective as the standard anti-microbial treatment and that the combination of both of these therapeutic approaches is the one that results in the quickest decrease of pulmonary CFU. This accelerated microbial clearance is of great relevance to the human disease because, in principle, it could reduce the length of chemotherapeutic regimens. Finally, despite the efficacy of NA in inhibiting COX-2 activity and the great advantages of SBG as a TGF-β inhibitor (discussed elsewhere, López-Casillas et al., submitted), it must be mentioned that these are not the only agents endowed with such pharmacological properties. Given the abundance of anti-TGF-β agents developed for anti-neoplasic treatment [39] and the existence of many pharmaceuticals capable of inhibiting prostaglandin synthesis, it should not be difficult to devise an immunotherapeutic approach similar to the one we have described, for the successful treatment of human tuberculosis and of any other infectious diseases in which the cellular immune response is compromised for similar reasons.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grants from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (to F.L.-C.), the International Centre for Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology (to F.L.-C.), the Wellcome Trust (to R.H.-P.), the European Union International Cooperation with Developing Countries (to R.H.-P.) and Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología, Mexico (to F.L-C. and R.H.-P.). We thank Dr Juan Burgueño for his assistance with the statistical analysis of data.

References

- 1.Gandy M, Zumla A. Introduction. In: Gandy M, Zumla A, editors. The return of the white plague global poverty and the ‘new’ tuberculosis. London: Verso; 2003. pp. 7–12. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barnes PF. Immunotherapy for tuberculosis. Wave of the future or tilting at windmills? J Resp Crit Care Med. 2003;168:142–3. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2305001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Waldmann TA. Immunotherapy: past, present and future. Nature Med. 2003;9:269–77. doi: 10.1038/nm0303-269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaufmann SHE. How can immunology contribute to the control of tuberculosis? Nature Rev Immunol. 2001;1:20–30. doi: 10.1038/35095558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rook GAW, Dheda K, Zumla A. Immune responses to tuberculosis in devoloping countries; implications for new vaccine. Nature Rev Immunol. 2005;5:661–7. doi: 10.1038/nri1666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hernández-Pando R, Orozco H, Arriaga K, Sampieri A, Larriva-Sahd J, Madrid-Marina V. Analysis of the local kinetics and localization of interleukin-1 alpha, tumour necrosis factor-α and transforming growth factor-β, during the course of experimental pulmonary tuberculosis. Immunology. 1997;90:607–17. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1997.00193.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rangel-Moreno J, Estrada-García I, García-Hernández ML, Aguilar-León D, Marquez R, Hernández-Pando R. The role of protaglandin E2 in the immunopathogenesis of experimental pulmonary tuberculosis. Immunology. 2002;106:257–66. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2002.01403.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Toossi Z, Ellner JJ. The role of TGF-β in the pathogenesis of human tuberculosis. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1998;87:107–14. doi: 10.1006/clin.1998.4528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Onwubalili JK, Scott GM, Robinson JA. Deficient immune interferon production in tuberculosis. Clin Exp Immunol. 1985;59:405–13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rook GAW, Hernández-Pando R. The pathogenesis of tuberculosis. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1996;50:259–84. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.50.1.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cooper AM, Dalton DK, Stewart TA, Griffin JP, Russell DG, Orme IM. Disseminated tuberculosis in interferon-γ gene-disrupted mice. J Exp Med. 1993;178:2243–7. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.6.2243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chan J, Xing Y, Magliozzo RS, Bloom BR. Killing of virulent Mycobacterium tuberculosis by reactive nitrogen intermediates produced by activated murine macrophages. J Exp Med. 1992;175:1111–22. doi: 10.1084/jem.175.4.1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ellner JJ. The immune response in human tuberculosis – implications for tuberculosis control. J Infect Dis. 1997;176:1351–9. doi: 10.1086/514132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hirsch CS, Hussain R, Toossi Z, Dawood G, Shahid F, Ellner JJ. Cross-modulation by transforming growth factor β in human tuberculosis: suppression of antigen-driven blastogenesis and interferon γ production. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:3193–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.8.3193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hirsch CS, Ellner JJ, Blinkhorn R, Toosi Z. In vitro restoration of T cell responses in tuberculosis and augmentation of monocyte effector function against mycobacterium tuberculosis by natural inhibitors of transforming growth factor β. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:3926–31. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.8.3926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Letterio JJ, Roberts AB. Regulation of immune responses by TGF-β. Annu Rev Immunol. 1998;16:137–54. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.16.1.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tada T, Ohzeki S, Utsumi K. Transforming growth factor β induced inhibition of T cell function. J Immunol. 1991;146:1077–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pinson DM, Le Claire RD, Lorsbach RB, Parmely MJ, Russell R. Regulation by transforming growth factor β-1 of expression and function of the receptor for IFN-γ on mouse macrophages. J Immunol. 1992;149:2028–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Geiser AG, Letterio JJ, Kulkarni AB, Karlsson S, Roberts AB, Sporn MB. Transforming growth factor β1 (TGF-β1) controls expression of major histocompatibility genes in the postnatal mouse: aberrant histocompatibility antigen expression in the pathogenesis of the TGF-β1 null mouse phenotype. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:9944–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.21.9944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tsunawaki S, Sporn M, Ding A, Nathan C. Deactivation of macrophages by transforming growth factor β. Nature. 1988;334:260–2. doi: 10.1038/334260a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chantry D, Turner M, Abney E, Feldmann M. Modulation of cytokine production by transforming growth factor-β. J Immunol. 1989;142:4295–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ding A, Nathan CF, Graycar J, Derynck R, Stuher DJ, Srimal S. Macrophage deactivating factor and transforming growth factors beta 1, 2 and 3 inhibits induction of macrophage nitrogen oxide synthesis by IFN gamma. J Immunol. 1990;145:940–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wahl SM. Transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) in inflammation: a cause and a cure. J Clin Immunol. 1992;12:61–74. doi: 10.1007/BF00918135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hernández-Pando R, Orozco EH, Sampieri A, et al. Correlation between the kinetics of Th1/Th2 cells and pathology in a murine model of experimental pulmonary tuberculosis. Immunology. 1996;89:26–33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vilchis-Landeros MM, Montiel JL, Mendoza V, Mendoza-Hernández GL, López-Casillas F. Recombinant soluble betaglycan is a potent and isoform-selective transforming growth factor-β neutralizing agent. Biochem J. 2001;355:215–22. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3550215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hernández-Pando R, Pavon L, Orozco EH, Rangel J, Rook GAW. Interactions between hormone-mediated and vaccine-mediated immunotherapy for pulmonary tuberculosis in BALB/c mice. Immunology. 2000;100:391–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2000.00054.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hernández-Pando R, Orozco EH, Honour J, Silva P, Leyva R, Rook GAW. Adrenal changes in murine pulmonary tuberculosis; a clue to pathogenesis? FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 1995;12:63–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1995.tb00176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McCulloch CE, Searle SR. Generalized, linear and mixed models. New York: Wiley; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shull MM, Ormsby I, Kier AB, et al. Targeted disruption of the mouse transforming growth factor-β1 gene results in multifocal inflammatory response. Nature. 1992;359:693–9. doi: 10.1038/359693a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kulkarni AB, Huh C-G, Becker D, et al. Transforming growth factor β1 null mutation in mice causes excessive inflammatory response and early death. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:770–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.2.770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Border WA, Ruoslahti E. Transforming growth factor-β in disease: the dark side of tissue repair. J Clin Invest. 1992;90:1–7. doi: 10.1172/JCI115821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Atamas SP, Yurovsky VV, Wise R, et al. Production of type 2 cytokines by CD8+ lung cells is associated with greater decline in pulmonary function in patients with systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42:1168–79. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199906)42:6<1168::AID-ANR13>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hernández-Pando R, Aguilar D, Hernández ML, Orozco H, Rook G. Pulmonary tuberculosis in BALB/c mice with non-functional IL-4 genes: changes in the inflammatory effects of TNF-α and in the regulation of fibrosis. Eur J Immunol. 2004;34:174–83. doi: 10.1002/eji.200324253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee CG, Homer R, Zhu Z, et al. Interleukin-13 induces tissue fibrosis by selectively stimulating and activating transforming growth factor β1. J Exp Med. 2001;194:809–21. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.6.809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Belkaid Y, Rouse BT. Natural regulatory T cells in infectious disease. Nature Immunol. 2005;6:353–60. doi: 10.1038/ni1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hernández-Pando R, Rook GAW. The role of TNF-α in T cells mediated inflammation depends on the Th1/Th2 cytokine balance. Immunology. 1994;82:591. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rook GAW, Hernández-Pando R, Dheda K, Seah GT. IL-4 in tuberculosis: implications for vaccine design. Trends Immunol. 2004;25:483–8. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2004.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rook GAW, Dheda K, Zumla A. Do successful tuberculosis vaccines need to be immunoregulatory rather than merely Th1-boosting? Vaccine. 2005;23:2115–20. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.01.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dumont N, Arteaga CL. Targeting the TGFβ signalling network in human neoplasia. Cancer Cell. 2003;3:531–5. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00135-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]