Abstract

The objective of this work was to study the role of mannose-binding lectin (MBL) and C-reactive protein (CRP) in pneumococcal pneumonia, to determine whether MBL acts as an acute-phase reactant and whether the severity of the disease correlates with MBL levels. The study comprised 100 patients with pneumococcal pneumonia. The pneumonia severity score was calculated and graded into a risk class of mortality (Fine scale). The MBL genotypes and the levels of MBL and CRP at the acute and recovery phases were determined. Fifty patients with the wild-type MBL genotype showed higher MBL levels in each phase (P < 0·001) and an increased risk to developing bacteraemia, odds ratio (OR) 2·74, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1·01–7·52) (P = 0·02), but this did not correlate with the pneumonia severity class. CRP levels in the acute phase, 79·53 mg/l [standard deviation (s.d.) 106·93], were higher in the subjects with positive blood cultures (P = 0·003), and remained higher [20·12 mg/l (s.d. 31·90)] in the group of patients with an underlying disease (P = 0·01). No correlation was observed between the levels of MBL and CRP in each phase, or with the pneumonia severity score. We cannot conclude that MBL acts uniformly as an acute-phase reactant in pneumococcal pneumonia. MBL levels do not correlate well with the severity of the pneumonia. The risk of developing bacteraemia could be enhanced in individuals with the wild-type MBL genotype.

Keywords: acute phase proteins, community-acquired pneumonia, C-reactive protein, mannose-binding lectin, Streptococcus pneumoniae

Introduction

The estimated incidence of community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) in Spain is about 162 cases per 100 000 individuals, with 53 000 hospital admissions per year [1]. Streptococcus pneumoniae is the most important CAP aetiological agent and elicits a powerful inflammatory and immune response that relies upon a close relationship between innate and adaptive components of the host's immune system, with a release of inflammatory mediators, such as interleukin (IL)-6, which is the main inducer of the synthesis in hepatocytes of an acute-phase protein, the C-reactive protein (CRP) [2]. CRP plays a significant role in the defence against S. pneumoniae, binding the C polysaccharide of the cell wall, activating the classical complement pathway and favouring the opsonophagocytosis of these bacteria [3,4].

Interest in CRP has increased during recent years because changes in its concentration have been used as a marker related to the risk of future coronary events or as a measure of the activity of some rheumatological disorders. In the case of CAP, higher plasma levels of CRP have been encountered in patients with bacterial pneumonia, in contrast to viral aetiology, and have been related to the severity of the disease, suggesting that CRP levels may help to evaluate a patient's management and to monitor response to antibiotic therapy [5–8]. However, a recently published systematic review has concluded that testing for CAP is neither sensitive nor specific enough to rule in or rule out a radiological infiltrate or the bacterial aetiology of the respiratory tract infection [9].

Mannose-binding lectin (MBL) is a plasma lectin with a high affinity for N-acetyl glucosamine, a component of peptidoglycan, present on the surface of microbes but not on human cells. MBL interacts with both the innate and adaptive immune system, and has some homologies with CRP: it is synthesized by hepatocytes, takes part in the opsonophagocytosis of bacteria and initiates the complement cascade (via the lectin pathway). MBL has also been suggested to act as an acute-phase reactant, and that heat shock and proinflammatory cytokines could stimulate its production in vitro [10,11]. The role of MBL in the risk of developing bacterial infections has been studied with conflicting results. It seems that MBL gene mutations determine a susceptibility to infection in patients with systemic lupus erythematosis and HIV infection, influence the severity of lung disease in patients with cystic fibrosis and increase the number of episodes of acute respiratory infection in children [12–15]. Moreover, homozygotes for MBL variants could be at increased risk of developing invasive infections by S. pneumoniae, as has been demonstrated previously [16], although this relationship was not encountered in another published work [17].

The objective of the present study was to evaluate the role of MBL in pneumococcal pneumonia by comparing the levels of MBL and CRP, to determine whether MBL really acts as an acute-phase reactant in this setting, and to establish whether the severity of the disease correlates with lower MBL levels. The latter issue gains in importance, as MBL therapy could be a possible option to treat deficiency states, as has been demonstrated in cystic fibrosis [18].

Materials and methods

The study was conducted in Son Dureta Hospital, a 900-bed tertiary referral centre, and Son Llàtzer Hospital, a 350-bed community centre (Mallorca, Spain).

Selection of patients and definitions

From 1 June 2003 to 30 June 2005 we studied all consecutive adult patients (> 18 years old) with pneumococcal pneumonia with clinical features and/or X-ray findings. The microbiological criteria used to confirm the pneumococcal aetiology were: (1) at least one blood or pleural fluid culture positive for S. pneumoniae, (2) one sputum culture positive for the same bacteria in addition to a positive determination of rapid immunochromatographic urinary antigen test or (3) in those cases in which bronchoscopy procedures were carried out, a quantitative bacterial recount of at least 103 colony-forming units (CFU)/ml for telescope catheter culture; 104 CFU/ml for bronchoalveolar lavage or 105 CFU/ml for bronchoaspirate were considered significant.

Patients were recruited from the emergency departments of either of the two participant hospitals and a blood sample (acute phase) was obtained immediately after the microbiological diagnosis was confirmed. When a patient with a confirmed microbiological pneumococcal pneumonia did not meet the criteria for hospital admission they were requested by telephone to attend the out-patient clinic to provide a blood sample. At least 4 weeks after the resolution of the acute pneumococcal infection, the patients were requested to visit the out-patient clinic to provide another blood sample (recovery phase).

Demographic variables and comorbidities were collected for each patient. In each episode the pneumonia severity score was calculated and graded into a risk class of mortality by using the Fine scale [19], considering three groups: low risk (classes I, II and III), moderate risk (class IV) and high risk (class V).

Patients with nosocomial infections, primary immunodeficiencies (routine immunological tests were carried out to evaluate their immunological status), those who died before the microbiological diagnosis was obtained, or who did not turn up at the out-patient clinic during the acute phase and those who refused to sign the informed consent were excluded. For patients with recurrent pneumonia episodes, only the first episode was considered.

Laboratory tests

Blood samples were collected aseptically into plain and ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA) tubes in the first 48 h of hospital admission. For all samples, serum was separated immediately and transferred into cryovials and preserved at − 80°C for further testing. EDTA blood samples were used for genomic DNA isolation. DNA isolation was carried out using the proteinase K method.

CAP was determined by nephelometry (BNAII, Dade Behring® Marburg, Germany) using a highly sensitive commercial kit (Dade-Behring®). The cut-off point used to detect abnormal values was > 3 mg/dl, as suggested by the CRP manufacturer.

Mannose-binding lectin (MBL) serum concentrations were determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) performed in microwells coated with a monoclonal antibody against the MBL carbohydrate-binding domain in a commercial kit (oligomerized mannan-binding lectin; AntibodyShop®, Gentofte, Denmark). MBL concentrations in serum were expressed as ng/ml.

For the MBL genotype, genotyping was perfomed by polymerase chain reaction with sequence-specific primers (PCR–SSP). Primers and conditions for amplification of MBL mutations were used according to Steffensen et al.'s [20] method, with a personal modification of the temperature conditions for amplification of exon 1 with mix B (20 s at 60°C instead of 58°C). Analysis was accomplished by subjecting samples of genomic DNA from each individual to a maximum of 17 PCR reactions carried out under three different PCR conditions with various MgCl2 concentrations. The genotypes were determined by the presence or absence of a specific band after electrophoresis in a 2% agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide visualized by ultraviolet light and photographically recorded (data not shown).

Ethics

All the patients were required to sign an informed consent and the study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Comunitat de les Illes Balears.

Statistical analysis

First, a descriptive analysis of the population of the study was made. In the bivariate analysis, we used χ2 tests to compare qualitative variables. Comparison of the quantitative variables was carried out using non-parametric tests (Mann–Whitney test). For the correlation analysis we calculated Pearson's coefficient. Statistical significance was taken as a P-value less than 0·05. The risk of bacteraemia associated with MBL genotypes was estimated using the calculation of odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence interval (CI). Statistical power was at least 80%.

The analysis was carried out with spss 12·0 and GraphPad Prism4 software.

Results

One hundred patients (68 male, 32 female) with pneumococcal pneumonia (53 with bacteraemia) were included. Fifty-one patients had at least one comorbidity, mainly chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (33 cases), and 15 subjects were infected by HIV-1. Forty-three patients were classified into the low-risk mortality class and 57 into the moderate–high-risk classes. Forty-three patients' samples of the recovery phase were processed. Demographic and general characteristics of the study population are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic and general characteristics of the study population.

| n = 100 | |

|---|---|

| Male/female | 68/32 |

| Age (years; mean/range) | 58·27 (21–96) |

| Comorbidity | 51 |

| COPD | 33 |

| Diabetes | 9 |

| Cardiac failure | 9 |

| Hepatopathy | 7 |

| Corticosteroids/immunosuppressors | 4 |

| Neutropenia | 2 |

| Renal insufficiency | 2 |

| Solid neoplasm | 2 |

| HIV-1 infection | 15 |

| HAART | 8 |

| CD4 cell count/cell/µl (median/range) | 135 (36–500) |

| Smokers | 46 |

| Alcoholism | 4 |

| Drug abuse (active) | 8 |

| Bacteraemia | 53 |

| Mortality risk class (Fine) | |

| Low I | 15 |

| Low II | 11 |

| Low III | 17 |

| Moderate IV | 42 |

| High V | 15 |

COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; HAART: highly active anti-retroviral therapy.

Fifty patients presented the wild-type MBL genotype (AA), 43 were heterozygous (AO) and four homozygous (OO) for the MBL variants. In three cases it was not possible to determine the genotype. The patients with the AA genotype showed higher levels of MBL than the two mutated groups (AO/OO) considered together, in the acute (P < 0·001) and recovery phases (P < 0·001). Non-statistical differences were observed between the MBL genotype and the levels of CRP (Table 2).

Table 2.

Mannose-binding lectin (MBL) and C-reactive protein (CRP) levels according to the MBL genotype. The number of patients, grouped by risk class, with very low levels of MBL in the acute phase is also shown.

| Genotype AA | Genotype AO/OO | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MBL acute (ng/ml) | |||

| Mean (s.d.) | 4298·81 (2109·34) | 863·83 (675·12) | < 0·001 |

| Median (range) | 4225 (1150–10000) | 700 (35–2500) | |

| MBL recovery (ng/ml) | |||

| Mean (s.d.), | 3576·19 (1246·25) | 695·56 (523·37) | < 0·001 |

| Median (range) | 4000 (1200–5750) | 650 (35–2100) | |

| MBL acute < 500 ng/ml | |||

| Low-risk | – | 7 cases | – |

| Moderate–high-risk | – | 6 cases | |

| CRP acute (mg/l) | |||

| Mean (s.d.) | 67·69 (105·28) | 54·95 (70·37) | n.s. |

| Median (range) | 34 (1–578) | 22 (1–265) | |

| CRP recovery (mg/l) | |||

| Mean (s.d.) | 10·12 (14·76) | 12·50 (26·92) | n.s. |

| Median (range) | 4·50 (1–67) | ;3 (0–125) | |

The relation between MBL genotypes and the presence or absence of bacteraemia is shown in Table 3. Patients with the AA genotype showed a higher risk of developing bacteraemia, OR 2·74 (95% CI 1·01–7·52, P = 0·02). No statistical differences were found between risk class of mortality (Fine scale) and MBL genotypes (Table 3). Thirteen patients with the AO/OO genotype presented MBL levels lower than 500 ng/ml (seven in the low- and six in the moderate–high-risk groups) in the acute phase, but no differences were detected when compared with those having the MBL acute level above that value.

Table 3.

Mannose-binding lectin (MBL) genotypes in relation to bacteraemia and risk class of mortality (Fine scale).

| Genotype AA | Genotype AO/OO | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blood cultures* | |||

| (a) Positive | 32 | 18 | 50 |

| (b) Negative | 13 | 20 | 33 |

| Risk class* | |||

| (a) Low | 18 | 22 | 40 |

| (b) Moderate–high | 32 | 15 | 47 |

In 14 episodes blood cultures were not performed and in three cases MBL genotypes were not performed.

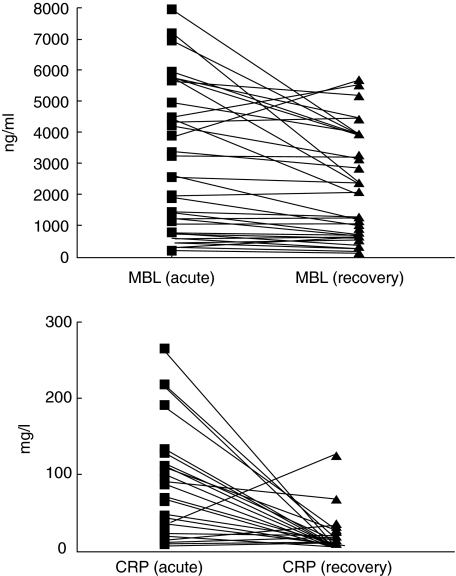

Although the mean and median of the MBL levels, both in acute and in recovery phases, were higher for the moderate–high-risk group, these differences did not reach statistical significance. The mean values of CRP in acute phase were similar for both groups, and only the CRP level in the recovery phase was statistically higher (P = 0·005) in the moderate–high-risk group (Table 4). When we compared the MBL levels with the severity group for each of the genotypes (AA versus AO/OO) in the acute and recovery phases, these differences remained non-significant (Table 4). Figure 1 represents the individual MBL and CRP concentrations of the 43 patients with two paired samples (acute and recovery phases). Fifty-four patients were lost to follow-up, 28 were AA and 26 were AA/OO, without differences in comparison with patients whose paired samples were obtained.

Table 4.

Mannose-binding lectin (MBL) and C-reactive protein (CRP) concentrations in the acute and recovery phases in accordance with the mortality risk group (Fine scale) for the whole study population. MBL concentration in each phase and risk group for the different MBL genotypes.

| Low-risk* | Moderate–high-risk** | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| The whole study population | |||

| MBL acute (ng/ml) | |||

| Mean (s.d.) | 2380·69 (2174·29) | 2990·00 (2451·03) | n.s. |

| Median (range) | 1450 (35–7250) | 2600 (90–10000) | |

| MBL recovery (ng/ml) | |||

| Mean (s.d.) | 1988·57 (1536·02) | 2391·20 (1871·05) | n.s. |

| Median (range) | 1850 (100–5250) | 2400 (35–5750) | |

| CPR acute (mg/l) | |||

| Mean (s.d.) | 68·29 (113·11) | 57·04 (70·94) | n.s. |

| Median (range) | 22 (1–578) | 31 (1–294) | |

| CRP recovery (mg/l) | |||

| Mean (s.d.) | 4·24 (6·36) | 15·77 (26·19) | 0·005 |

| Median (range) | 2 (0–25) | 6 (1–125) | |

| Restricted to AA genotype | |||

| MBL acute (ng/ml) | |||

| Mean (s.d.) | 4525·00 (1745·95) | 4185·71 (2291·04) | n.s. |

| Median (range) | 4500 (1400–7250) | 3750 (1150–10000) | |

| MBL recovery (ng/ml) | |||

| Mean (s.d.) | 3107·14 (1316·06) | 3810·71(1188·43) | n.s. |

| Median (range) | 2400 (1700–5250) | 4000 (1200–5750) | |

| Restricted to AO/OO genotypes | |||

| MBL acute (ng/ml) | |||

| Mean (s.d.) | 835·47 (704·97) | 897·50 (659·16) | n.s. |

| Median (range) | 675 (35–2500) | 750 (90–2200) | |

| MBL recovery (ng/ml) | |||

| Mean (s.d.) | 870·00 (678·60) | 584·55 (393·06) | n.s. |

| Median (range) | 720 (100–2100) | 580 (35–1300) | |

Includes: I, II and III Fine categories.

Includes: IV and V Fine categories.

Fig. 1.

The mannose-binding lectin and C-reactive protein concentrations of each of the 43 patients with two paired samples in the acute and recovery phases.

At each phase, the mean levels of MBL of the patients with bacteraemia were higher than those with negative blood cultures [acute: 3038·49 (s.d. 2218·70) ng/ml versus 2532·17 (s.d. 2590·70) ng/ml; recovery: 2751·94 (s.d. 1781·36) ng/ml versus 1923·12 (s.d. 1751·47) ng/ml] but without statistical significance. In the acute phase, the levels of CRP were significantly higher in the subjects with positive blood cultures [79·53 (s.d. 106·93) mg/l versus 36·68 (s.d. 63·77) mg/l (P = 0·003)], but in the recovery phase these differences disappeared [6·03 (s.d. 7·58) mg/l versus 12·78 (s.d. 17·02) mg/l].

The levels of CRP in the recovery phase remained higher in the group of patients with an underlying disease in comparison with the previously healthy ones [20·12 mg/l (s.d. 31·90) versus 5·77 mg/l (s.d. 7·42) (P = 0·01)].

There was no correlation between the levels of CRP and MBL either in the acute phase (P = 0·87) or in the recovery phase (P = 0·53). Finally, no correlation was observed between the pneumonia severity score at hospital admission and the acute values of CRP (P = 0·78) or MBL (P = 0·21).

One patient died, in relation to the pneumococcal pneumonia. She was an elderly woman with chronic hepatopathy and cardiac failure, classified at admission as high risk. She presented the AO genotype, and the values of CRP and MBL in acute phase were 138 mg/l and MBL 215 ng/ml, respectively. Four additional patients died in the 3 months following the acute episode, two with exacerbated COPD, one with a non-Hodgkin lymphoma and one with diffuse pleural carcinomatosis. When we compared the levels of CRP and MBL in the acute phase of the deceased cases with the remaining 95 surviving subjects no statistical differences were detected.

The previously exposed statistical analysis was repeated excluding the 15 patients with HIV-1 infection, also excluding the 51 patients with comorbities, and the results obtained were comparable with those of the whole population (data not shown).

Discussion

The properties of MBL as an acute-phase reactant have been studied in different scenarios since the first description [10], that MBL synthesis is induced as a part of the acute response. Neth et al. observed a higher MBL concentration in children with malignancy than in healthy individuals [21]. Two other studies have analysed the behaviour of MBL in patients undergoing major surgery, with discordant results. In the first study, in sequential blood samples of 11 patients after major hip surgery, increases in MBL concentration between 1·5 and threefold were observed [22]. In the same study, a rise in MBL levels was observed in five patients after a malaria attack. In another study including patients who underwent gastrointestinal resections for malignant disease, the MBL levels did not rise immediately after surgery, but lower MBL levels were associated with the occurrence of postoperative infections [23]. However, although both studies were conducted in the postoperative setting the population analysed was different, and in the second study the observation period was shorter, with only two blood samples tested (1 and 3 days after the surgery).

A study of critically ill patients admitted to an intensive care unit (ICU) concluded that, even though the MBL levels on day 5 of admission and on the last day of the ICU stay were higher in the non-survivors, these levels were not related to the outcome in the multivariate analysis when adjusted for all risk factors upon admission [24]. The authors observed that the MBL concentration increased during the ICU stay; however, no correlation was observed with CRP levels at any point. In another study including patients with severe infection and proven sepsis (bloodstream infection or community-acquired pneumonia), MBL concentrations behaved as an acute-phase reactant, defined as a 25% increase or decrease from baseline levels, in 31·3% and 27·3% of the cases, respectively, with 41·4% of the patients exhibiting steady-state levels throughout the study period. The authors concluded that the MBL concentrations demonstrated a variable acute-phase response [25].

The present study has failed to establish a correlation between MBL levels and the severity of pneumococcal pneumonia, evaluated with a well-validated scale. Moreover, no differences between MBL levels during the acute episode and in the recovery phase were detected, and no correlation was observed with the CRP levels at any of the time-points. So, we agree with the conclusions reached in the previous study [25], that MBL does not act uniformly in all patients as an acute-phase reactant. Furthermore, in the group of patients with underlying disease the CRP concentration in the recovery phase remained significantly higher, probably indicating a persistent inflammatory state. The same was not observed for MBL levels, supporting the absence of parallelism between both proteins.

As expected [26–28], MBL concentrations were lower for patients with the mutated MBL genotype. In our study it was not possible to establish a relationship with the severity of the pneumonia, nor for the subgroup of cases with very low levels of MBL, although the number of patients in this situation was limited. Although levels below 500 ng/ml have been observed more frequently among non-survivors, these differences disappeared when corrected for the risk factors at admission [24].

Interestingly, the patients with the wild-type MBL genotype had a greater risk of developing bacteraemia. When the total study population was considered, in patients with positive blood cultures the MBL levels tended to be higher, although without reaching statistical significance. To explain this finding, which seems to render bloodstreams more susceptible to invasion, it can be speculated that, as has been reported [29], the N-acetylglucosamine of the cell wall of Gram-positive bacteria is a biologically relevant ligand for MBL and that MBL inhibits peptidoglycan-induced production of proinflammatory cytokines, suggesting that MBL may down-regulate macrophage-mediated inflammation and, furthermore, that MBL enhances phagocyte recruitment, thus hypothetically favouring the bloodstream entrance of the bacteria by proper cell-surface anchoring.

CRP levels in the acute phase did not correlate with the severity of the pneumonia; the data were not concordant with those reported previously [8]. Some factors can justify these differences: our study was restricted only to episodes of well-documented pneumococcal pneumonia attended at hospital emergencies, and the CRP level was determined not immediately after admission, but only when a microbiological confirmation was obtained; because the plasma half-life of CRP is about 19 h [30], the stimulus for its increased production could have ceased after the antibiotic treatment was initiated, thus not reflecting the real values at admission. However, patients with pneumococcal bacteraemia presented higher CRP values in the acute phase than those with negative blood cultures, a circumstance that has also been emphasized by other authors [5].

There are some possible limitations to our study. As it was conducted in the ambit of hospital emergencies, less severe episodes of pneumonia attended normally in the primary care setting could not be included, although 43 of the episodes were grouped into the low-risk classes, with an estimated risk of mortality under 1%. We used restrictive criteria to warrant the aetiology of the pneumonia, excluding other possible pneumococcal episodes such as those without a confirmed microbiological diagnosis, with an isolated positive urinary antigen or an isolated sputum smear. Determination of MBL and CRP levels was made when the microbiological confirmation was obtained. This delay, as commented above, could have influenced the drop in the CRP concentrations, but probably did not affect the MBL concentrations because the half-life of circulating MBL, as observed from infusion studies in MBL-deficient humans, has been estimated to be as long as 5–7 days [31].

Although 42 and 15 patients in our series were grouped into moderate- and high-risk classes (estimated risk of mortality 9·3% and 27%, respectively) only one patient died in relation to the acute episode, so the analysis was extended to cover mortality within the following 3 months. It is possible that some patients with pneumococcal pneumonia could not be included because they died before a microbiological diagnosis was obtained.

In summary, with the data presented here we cannot conclude that the MBL acts as an acute phase reactant in pneumococcal pneumonia. Although the study was not designed to decide the need for hospitalization of patients with community-acquired pneumococcal pneumonia, it seems that MBL cannot be used for this purpose, as the levels of this lectin do not correlate with the severity of the pneumonia. The role of MBL could be different in pneumonias of another aetiology or in other clinical situations (i.e. immunosuppressed patients), as the antimicrobial mechanism of MBL will depend on the nature of the infecting organism and the immunological state of the host.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by two grants from Fondo de Investigaciones Científicas de la Seguridad Social (FISS Exp. 03/1054) and Conselleria de Salut i Consum, Govern Balear (Exp. 62/2003).

References

- 1.Almirall J, Bolibar I, Vidal J, et al. Epidemiology of community-acquired pneumonia in adults: a population based study. Eur Resp J. 2000;15:757–63. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3003.2000.15d21.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Castell JV, Gomez-Lechon MJ, David M, Fabra R, Trullen R, Heinrich PC. Acute-phase response of human hepatocytes: regulation of acute-phase protein synthesis by interleukin-6. Hepatology. 1990;12:1179–86. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840120517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Szalai AJ, Agrawal A, Greenhough TJ, Volanakis JE. C-reactive protein: structural biology, gene expression and host defense function. Immunol Res. 1997;16:127–36. doi: 10.1007/BF02786357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaplan MH, Volanakis JE. Interaction of C-reactive protein complexes with the complement system. I. Consumption of human complement associated with the reaction of C-reactive protein with pneumococcal C polysaccharide and the choline phosphatides, lecitin and sphingomyelin. J Immunol. 1974;112:2135–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ortqvist A, Hedlund J, Wretlind B, Carlstrom A, Kalin M. Diagnostic and prognostic value of interleukin-6 and C-reactive protein in community-acquired pneumonia. Scand J Infect Dis. 1995;27:457–62. doi: 10.3109/00365549509047046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hedlund J, Hansson LO. Procalcitonin and C-reactive protein levels in community-acquired pneumonia: correlation with etiology and prognosis. Infection. 2000;28:68–73. doi: 10.1007/s150100050049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.García Vázquez E, Martínez JA, Mensa J, et al. C-reactive protein levels in community-acquired pneumonia. Eur Respir J. 2003;21:702–5. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00080203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Almirall J, Bolibar I, Toran P, et al. Contribution of C-reactive protein to the diagnosis and assessment of severity of community-acquired pneumonia. Chest. 2004;125:1335–42. doi: 10.1378/chest.125.4.1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van der Meer V, Neven AK, van der Broek PJ, Assendelft WJJ. Diagnostic value of C reactive protein in infections of the lower respiratory tract: systematic review. BMJ. 2005;331:26. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38483.478183.EB. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ezekowitz RA, Day LE, Herman GA. A human mannose-binding protein is an acute-phase reactant that shares sequence homology with other vertebrate lectins. J Exp Med. 1988;167:1034–46. doi: 10.1084/jem.167.3.1034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arai T, Tabona P, Summerfield JA. Human mannose-binding protein gene is regulated by interleukins, dexamethasone and heat shock. Q J Med. 1993;86:575–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garred P, Madsen HO, Halberg P, et al. Mannose-binding lectin polymorphisms and susceptibility to infection in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthitis Rheum. 1999;42:2145–52. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199910)42:10<2145::AID-ANR15>3.0.CO;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hundt M, Heiken H, Schmidt RE. Association of low mannose-binding lectin serum concentrations and bacterial pneumonia in HIV infection. AIDS. 2000;14:1853–4. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200008180-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garred P, Pressler T, Madsen HO, et al. Association of mannose-binding lectin gene heterogeneity with severity of lung disease and survival in cystic fibrosis. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:431–7. doi: 10.1172/JCI6861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koch A, Melbye M, Sorensen P, et al. Acute respiratory tract infections and mannose-binding lectin insufficiency during early childhood. JAMA. 2001;285:1316–21. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.10.1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roy S, Knox K, Segal S, et al. MBL genotype and risk of invasive pneumococcal disease: a case–control study. Lancet. 2002;359:1569–73. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08516-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kronborg G, Weis N, Madsen HO, et al. Variant mannose-binding lectin alleles are not associated with susceptibility to or outcome of invasive penumococcal infection in randomly included patients. J Infect Dis. 2002;185:1517–20. doi: 10.1086/340216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garred P, Pressler T, Lanng S, et al. Mannose-binding lectin (MBL) therapy in an MBL-deficient patient with severe cystic fibrosis lung disease. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2002;33:201–7. doi: 10.1002/ppul.10064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fine MJ, Auble TE, Yealy DM, et al. A prediction rule to identify low-risk patients with community-acquired pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:243–50. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199701233360402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Steffensen R, Thiel S, Varming K, Jersild C, Jensenius JC. Detection of structural gene mutations and promoter polymorphisms in the mannan-binding lectin (MBL) gene by polymerase chain reaction with sequence-specific primers. J Immunol Meth. 2000;241:33–42. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(00)00198-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Neth O, Hann I, Turner MW, Klein NJ. Deficiency of mannose-binding lectin and burden of infection in children with malignancy: a prospective study. Lancet. 2001;358:614–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05776-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thiel S, Holmskov U, Hviid L, Laursen SB, Jensenius JC. The concentration of the C-type lectin, mannan-bindig protein, in human plasma increases during and acute phase response. Clin Exp Immunol. 1992;90:31–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1992.tb05827.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Siassi M, Hohenberger W, Riese J. Mannan-binding lectin (MBL) serum levels and post-operative infections. Biochem Soc Trans. 2003;31:774–5. doi: 10.1042/bst0310774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hansen TK, Thiel S, Wouters PJ, Christiansen JS, Van den Berghe G. Intensive insulin therapy exerts antiinflammatory effects in critically ill patients and counteracts the adverse effect of low mannose-binding lectin levels. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:1082–8. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-021478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dean MM, Minchinton RM, Heatley S, Eisen DP. Mannose binding lectin acute phase activity in patients with severe infection. J Clin Immunol. 2005;25:346–52. doi: 10.1007/s10875-005-4702-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Madsen HO, Garred P, Thiel S, et al. Interplay between promoter and structural gene variants control basal serum level of mannan-binding protein. J Immunol. 1995;155:3013–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Minchinton RM, Dean MM, Clark TR, Heatley S, Mullighan CG. Analysis of the relationship between mannose-binding lectin (MBL) genotype, MBL levels and function in an Australian blood donor population. Scand J Immunol. 2002;56:630–41. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.2002.01167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mead R, Jack D, Pembrey M, Tyfield L, Turner M. Mannose-binding lectin alleles in a prospectively recruited UK population The ALSPAC Study Team, Avon Longitudinal Study of Pregnancy and Childhood. Lancet. 1997;349:1669–70. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(05)62635-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nadesalingam J, Dodds AW, Reid KB, Palaniyar N. Mannose-binding lectin recognizes peptidoglycan via the N-acetyl glucosamine moiety, and inhibits ligand-induced proinflammatory effect and promotes chemokine production by macrophages. J Immunol. 2005;175:1785–94. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.3.1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vigushin DM, Pepys MB, Hawkins PN. Metabolic and scintigraphic studies of radioiodinated human C-reactive protein in health and disease. J Clin Invest. 1993;91:1351–7. doi: 10.1172/JCI116336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Valdimarsson H, Stefansson M, Vikingsdottir T, et al. Reconstitution of opsonizing activity by infusion of mannan-binding lectin (MBL) to MBL-deficient humans. Scand J Immunol. 1998;48:116–23. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.1998.00396.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]