Abstract

Summary

Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita is an autoimmune blistering disease characterized by circulating and skin basement membrane-bound IgG autoantibodies to type VII collagen, a major structural protein of the dermal–epidermal junction. Regulatory T cells (Treg) suppress self antigen-mediated autoimmune responses. To investigate the role of Treg in the the autoimmune response to type VII collagen in a mouse model, a monoclonal antibody against mouse CD25 was used to deplete Treg. A recombinant mouse type VII collagen NC1 domain protein and mouse albumin were used as antigens. SKH1 mice were used as a testing host. Group 1 mice received NC1 immunization and were functionally depleted of Treg; group 2 mice received NC1 immunization and rat isotype control; and group 3 mice received albumin immunization and were functionally depleted of Treg. Results demonstrated that anti-NC1 IgG autoantibodies with high titres, as determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and Western blotting, developed in all mice immunized with NC1 (groups 1 and 2), but were undetected in group 3 mice. The predominant subclasses of anti-NC1 autoantibodies were IgG1, IgG2a and IgG2b; furthermore, these antibodies carried only the kappa light chain. IgG autoantibodies in the sera of NC1-immunized mice reacted with mouse skin basement membrane in vitro and deposited in skin basement membrane in vivo as detected by indirect and direct immunofluorescence microscopy, respectively. Our data suggest that the development of autoimmunity against type VII collagen in mice is independent of Treg function and the autoimmune response is mediated by both Th1 and Th2 cells. We speculate that the basement membrane deposition of IgG may eventually lead to blister development.

Keywords: Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, regulatory T cells and animal model, type VII collagen

Introduction

Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita (EBA) is an autoimmune-mediated subepidermal blistering skin disease that is characterized by blisters and scarring (particularly on the extensor skin surfaces) on clinical examination, subepidermal blister on histopathological examination [1,2], linear IgG deposition in the skin basement membrane zone on immunopathological examination [1,2] and IgG circulating autoantibodies that bind the lamina densa/sublamina densa and recognize the type VII collagen, the major component of anchoring fibril in the skin basement membrane [1,3]. Type VII collagen is a homo-trimer molecule consisting of three identical alpha 1 chains, each of which is composed of NC1 domain (145-kDa), a central collagenous triple helical domain (145-kDa) and a smaller C-terminal NC2 domain (34-kDa) [4]. The NC1 domain of the molecule, located at the N-terminus of type VII collagen, has been found to be a major antigenic epitope region of EBA autoantibodies [5–7]. The pathogenic relevance of NC1 protein has been demonstrated in a passive transfer experimental mouse model of EBA, in which rabbit antibodies raised against either human or mouse type VII collagen NC1 domain were able to induce blisters in mice [8,9]. Subsequently, the NC2 domain of the molecule, located at the C-terminus of type VII collagen, has also been identified as an antigenic epitope region of the EBA autoantibodies [4]. The critical pathogenic epitope of EBA, however, is currently not yet delineated, as the passive transfer experiments were conducted by polyclonal antibodies raised against a large segment of the NC1 protein [8,9]. There are two major clinical subsets of EBA, a more common scarring subtype that affects predominantly the trauma prone extensor skin surfaces [2] and a more rare non-scarring subtype that affects the skin surface in a generalized manner [2,10]. A related disease termed bullous systemic lupus erythematosus (BSLE) is an autoimmune subepidermal blistering skin disease due to autoantibodies targeting type VII collagen occurring in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus [7]. Although the majority of patients with EBA have IgG class autoantibodies to type VII collagen, few were found to have IgA class autoantibodies instead [11]. EBA as a whole is a rare autoimmune disease. A survey in Europe suggests that the incidence of EBA is estimated to be 0·17–0·26 per million people [12]. Because EBA is such a rare disease, it is extremely difficult to perform any meaningful clinical studies in human patients to investigate the pathogenesis of disease or to evaluate optimal treatment options. To make things even more difficult, EBA is one of the chronic, autoimmune blistering diseases known to be resistant to conventional treatments [2]. Currently, there is no target-specific treatment available for EBA. Patients are treated with systemic immunosuppressants and encounter many medication side effects such as steroid-induced diabetes and osteoporosis [2,13]. Although EBA is a rare disease, it causes substantial morbidity to the affected individuals [1,2]. The associated scarring and nail malformation prohibit patients from participating in any kind of sport activities that may involve physical contact. Due to the rarity of epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, a mouse model would be extremely beneficial to investigate disease pathogenesis and optimal treatments.

Treg are potent immunoregulatory cells that account for approximately 5–10% of peripheral CD4+ cells co-expressing CD25 [interleukin (IL)-2 receptor α chain]. They inhibit in vitro proliferation of T cells including CD4+ CD25– and CD8+ subsets [14], although Treg themselves are non-proliferative to in vitro TCR stimulation [14]. Treg may play a significant role in the regulation of autoimmunity against self antigens [15,16]. In certain well-recognized autoimmune diseases such as pemphigus vulgaris and systemic lupus erythematosus, Treg was found to be diminished in number or in function [17–19]. Experimental depletion of Treg by monoclonal anti-CD25 antibodies has led to the development of autoimmune thyroiditis [20], and experimentally administered Treg inhibited development of autoimmune gastritis and encephalomyelitis [21,22]. As there is no existing knowledge regarding the role of Treg in controlling the development of human EBA, we decided to investigate its role in the induction of antoimmune response against self NC1. It is now clear that anti-CD25 monoclonal antibody treatment functionally depleted Treg by shedding the surface expression of CD25, without physically destroying the Treg [23]. Specifically, anti-CD25 depletes the CD4/CD25 double-positive T cells, but not the CD4/forkhead box p3 (Foxp3) double-positive T cells, while eliminating the Treg functions [23].

In the present study, we have generated a recombinant protein encoding the NC1 domain of the mouse type VII collagen and have confirmed that this recombinant protein is indeed a skin basement membrane protein by immunizing rat with this recombinant protein and by demonstrating the binding of rat antibody to mouse skin basement membrane zone. Furthermore, we have successfully induced autoimmunity against mouse type VII collagen NC1 domain in immune-competent SKH1 hairless mice. All the mice immunized against mouse NC1 protein, regardless whether or not they have an intact regulatory T cell system, developed strong IgG autoantibody responses to the NC1 protein and these IgG autoantibodies bound to the skin basement membrane zone. The majority of IgG antibodies belonged to IgG1, IgG2a and IgG2b. No IgA class autoantibodies to type VII collagen were detected in our model.

Materials and methods

Animals

Sprague–Dawley rats (Harlan, Madison, WI, USA) were used for production of polyclonal antibodies against mouse NC1 recombinant protein. Six- to 8-week-old female immune-competent SHK1 hairless mice (Charles Rivers, Wilmington, MA, USA) were used as the host for induction of autoimmunity against NC1. The study complied with the Animal Care Policies and Procedures of the University of Illinois at Chicago.

Cloning and generation of a recombinant mouse type VII collagen NC1 domain

The first-strand cDNA synthesis was accomplished using mouse total skin RNA (Origene, Rockville, MD, USA) with a reverse transcription kit and Random Decamers primer (RETROscript kit) purchased from Ambion (Austin, TX, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed with NC1-sense (5′- CGACTCCTGGTCGCTGCGCTC-3′) and NC1-anti-sense primer (5′- CTGAGCACCCACTCGAGCAGA-3′) using Tag DNA polymerase. PCR was performed initially at 95°C for 3 min, followed by a 35-cycle run (94°C for 1 min, 55°C for 1 min, 72°C for 2 min), and then followed by a final extension at 72°C for 5 min. The PCR products generated were stained with ethidium bromide and examined in 1% agarose gel for correct size. The DNA product was purified from the gel Gene Clean Spin Kit (Q.BIO Gene at Morgan, Irvine, CA, USA) and then sequenced and compared with the published mouse NC1 sequence [24,25]. To generate the recombinant protein, the purified PCR product was ligated to pBAD/Thio-TOPO expression plasmid vector (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) containing V5 epitope and 6 × His at the C-terminus. The vector with inserted NC1 DNA was transformed to Top 10 competent cell (Invitrogen). The clones containing insertions were amplified by PCR using NC1 primers. The positive clones were confirmed by DNA sequencing for correct sequence and in-frame orientation. The confirmed clones were grown in Lennox L Broth (LB) medium containing ampicillin and induced for 4·5 h by 1% arabinose. The recombinant protein was purified using a ProBond Purification System (Invitrogen). The purity was examined by sodium dodecyl sulphate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE).

Generation of rat polyclonal antibody against mouse NC1

Two Sprague–Dawley rats were immunized initially with 100 µg of purified NC1 protein in RIBI non-inflammatory adjuvant (Immunochem Research Inc., MT, USA), followed by immunization every 3 weeks thereafter with 50 µg NC1 recombinant protein with the same adjuvant. After four immunizations, post-immune sera were collected and stored at −80°C.

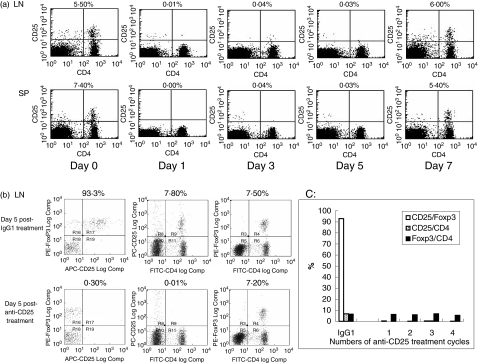

Production and testing of monoclonal antibody against mouse CD25

Hybridoma producing anti-mouse CD25 monoclonal antibody (clone PC61, rat IgG1) was purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) (Manassas, VA, USA). Cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium as instructed. To produce an isotype control for anti-CD25, hybridoma AIIB2 (rat IgG1) was purchased from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank (University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, USA). Cells were cultured in Iscove's Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium as instructed. The proteins in culture supernatant were precipitated by ammonium sulphate, and then the IgG antibodies were purified using protein G Sepharose 4 column (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ, USA). The purity of the IgGs was determined by SDS-PAGE to be > 98% (data not shown). In order to test the functional ability of anti-CD25 antibodies in depleting CD4+ CD25+ T cells, SKH1 mice were administered 500 µg intraperitoneally (i.p.) of either rat anti-CD25 or rat IgG isotype control. Mice that received the antibodies were killed at 24 h (day 1), 72 h (day 3), day 5 and day 7 after the administration of antibodies. The spleen and lymph nodes were harvested. The single-cell suspensions from these lymphoid organs were stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated anti-mouse CD4 and phycoerythrin (PE)-labelled anti-mouse CD25 (eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA). Flow cytometric analyses were performed to determine the presence or absence of the CD4/CD25 double-positive cells (Treg) using a fluorescence activated cell sorter (FACSCalibur; BD Bioscience, San Diego, CA, USA). As shown in Fig. 1a, the depletion of Treg (upper right quadrant of the flow diagram) was essentially completed at day 1, day 3 and day 5 in both lymphoid organs. However, by day 7 the percentages of Treg had recovered to normal levels. Isotype control rat IgG monoclonal antibody did not change the percentage of Treg throughout this 7-day test period (data not shown). We thus determined that administration of anti-CD25 every 5 days would be an efficient way to eliminate Treg. Foxp3 is a specific marker for Treg. It is crucial in the development and function of Treg [26–28]. To assure the complete depletion of Treg after a few cycles of anti-CD25 treatment and to monitor the changes of Foxp3 expression in CD4+ T cells, the following experiment was performed in five groups of SKH1 female mice. Each group contained two mice. Group 1 received a single dose of 500 µg isotype IgG. Group 2 received a single dose of 500 µg anti-CD25. Group 3 received two doses of 500 µg anti-CD25, 5 days apart. Group 4 received three doses of 500 µg anti-CD25, 5 days apart. Group 5 received four doses of 500 µg anti-CD25, 5 days apart. At day 5 of the last treatment of the antibodies, mice were killed and the spleen and lymph nodes were collected. The single-cell suspensions were then stained by FITC anti-CD4, PE anti-Foxp3 and allophycocyanin (APC) anti-CD25 (eBioscience) according to the instructions for the mouse Foxp3 detection kit and analysed by Cyan ADP Cytometer (DakoCytomation, Fort Collins, CO, USA). Our results were consistent with those demonstrated by Kohm et al., who used the same antibodies [23]. We found that whether the mice received one, two, three or four cycles of anti-CD25 monoclonal antibodies, there were essentially no CD4/CD25 double-positive T cells present, and that the anti-CD25 did not change the composition of CD4/FoxP3 double-positive T cells (Fig. 1b,c). This experiment confirmed that our method functionally depleted Treg without physically destroying them (Fig. 1b,c).

Fig. 1.

Effect of anti-CD25 monoclonal antibody. (a) SKH1 mice were intraperitoneally administered 500 µg purified rat anti-CD25. The mice which received the antibodies were killed at 24 h (day 1), day 3, day 5 or day 7 after the administration of the antibody. Spleen and lymph nodes were then harvested. Single-cell suspensions were stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated anti-mouse CD4 and phycoerythrin (PE)-labelled anti-mouse CD25 and analysed by fluorescence activated cell sorter (FACSCalibur). Results of injection of isotype rat Ig G are not shown. Day 0 indicates results of mice without anti-CD25 treatment. The numbers located above dot plots indicate the percentages of CD25+ cells in CD4+ cells. (b) To determine the expression of CD25 and forkhead boxp3 (Foxp3) in CD4+ cells after anti-CD25 antibody treatment, five groups of SKH1 mice were used. Group 1 received a single dose of 500 µg isotype IgG. Group 2 received a single dose of 500 µg anti-CD25. Group 3 received two doses of 500 µg anti-CD25, 5 days apart. Group 4 received three doses of 500 µg anti-CD25, 5 days apart. Group 5 received four doses of 500 µg anti-CD25, 5 days apart. At day 5 of the last injections, cells from the spleen and lymph node were stained by FITC-anti-CD4, PE-anti-Foxp3 and allophycocyanin (APC)-anti-CD25 and analysed by Cyan ADP flow cytometer. Data shown are results from lymph node cells in groups 1 and 2 after one anti-CD25 or IgG isotype injection. The numbers located above each dot plot in the left column indicate the percentages of CD25+ in Foxp3+ cells gated on CD4+ cells. The numbers located above each dot plot in the middle column indicate the percentages of CD25+ cells in CD4+ cells. The numbers located above each dot plot in the right column indicate the percentages of Foxp3+ cells in CD4+ cells. (c) Anti-CD25 inactivates Treg in a consistent manner: CD25+/Foxp3 (gated on CD4+), CD25+/CD4+ and Foxp3+/CD4+ cells in the lymph node were analysed after one, two, three and four cycles of anti-CD25 treatment, showing consistent inactivation of Treg, without physical depletion. Similar analyses for IgG1 isotype treatment obtained after one cycle treatment are shown on the far left for comparison. Similar results were obtained in the studies of the spleen cells (data not shown).

Induction of autoimmunity to recombinant mouse NC1

Three groups of female SKH1 mice were included. Each group comprised five mice. The first group received rat anti-CD25 (500 µg every 5 days) and mouse NC1 (50 µg) every 3 weeks. The second group received rat isotype control (500 µg every 5 days) and mouse NC1 (50 µg) every 3 weeks. The third group received rat anti-CD25 (500 µg every 5 days) and mouse albumin (50 µg) every 3 weeks. For the initial immunization, the immunogens were emulsified 1 : 1 (vol : vol) with complete Freunds' adjuvant (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) and for the subsequent immunizations, the immunogens were emulsified 1 : 1 (vol : vol) with incomplete Freunds' adjuvant (Sigma). Each immunization of NC1 or albumin proteins was administered 24 h after an anti-CD25 or isotype antibody treatment. Three months after the initiation of the immunization blood samples were obtained through orbital punctuation, and the titres of anti-NC1 recombinant protein in the sera were examined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), as described below. After we found high titres of autoantibodies to NC1 developed in both groups 1 and 2, showing no statistically significant difference (data not shown), we terminated the continuous injection of anti-CD25 antibody for groups 1 and 3 and isotype IgG for group 2 at the end of month 3. For the following months, groups 1 and 2 received NC1, and group 3 received albumin immunization without any antibody treatment. At the end of 5·5 months after the initial immunization, the mice were killed. The sera and skin (random front leg biopsy) from these mice were collected for further experiments.

ELISA

The ELISA for detecting type VII collagen autoantibodies was conducted as follows: a 96-well plate (Nunc-Immuno Plate, Nalge Nunc Int., Rochester, NY, USA) was coated with recombinant mouse NC1 (0·5 µg/ml, 100 µl) in carbonate buffer (pH 9·4) overnight at 4°C. The plate was then blocked with 2% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). After washing with PBS/0·5% Tween-20, mouse sera were diluted to 1 K (1000), 4 K, 8 K, 16 K, 32 K, 64 K, 128 K and 256 K with PBS, and the diluted sera was added to the NC1-coated wells and incubated. After washing, a 1 : 5000 diluted horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) was added and incubated. Finally, 3-ethylbenzthiazoline-6-sulphonic acid (ABTS) substrate (Zymed, South San Francisco, CA, USA) was added and the plate was read at 415 nm in a µQuant plate reader (Bio-TEK, Inc., Winooki, VT, USA). ELISA assays were also performed to characterize the subclasses and light chains of the IgG autoantibodies to NC1 as follows: for IgG subclass determination, a 96-well plate (Nunc-Immuno Plate, Nalge Nunc Int.) was coated with recombinant mouse NC1 and blocked as described above. After washing, the diluted (1 : 4000) mouse sera was added to the NC1-coated wells and incubated. After washing, a second antibody solution containing 1 : 1000 diluted alkaline phosphatase-conjugated rat anti-mouse IgG1, IgG2a, IgG2b or IgG3 monoclonal antibodies (BD Biosciences) was added and incubated. Finally, alkaline phosphatase yellow liquid substrate (Sigma) was added (200 µl/well). After a yellow reaction product formed, 3 N NaOH was added to stop the reaction. The plate was read at 405 nm. For light-chain autoantibody determination, a 96-well plate (Nunc-Immuno Plate, Nalge Nunc Int.) was coated with recombinant mouse NC1 and blocked as described above. After washing, the diluted (1 : 4000) mouse sera was added to the wells and incubated. After washing, a second antibody solution containing 1 : 1000 diluted biotin-conjugated rat anti-mouse kappa chain, lambda chain(1,2,3) monoclonal antibodies (BD Biosciences) was added and incubated, followed by incubation of streptavidin–peroxidase polymer (Sigma). Finally, tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) substrate (Sigma) was added. The plate was read at 655 nm. The function of the secondary antibody was validated by using a sandwich method: the plate was coated with unlabelled monoclonal rat anti-mouse IgG1 (BD Biosciences), followed by purified standard mouse IgG1 lambda (BD Biosciences) in serial dilutions, then by biotin-labelled anti-mouse lambda chain(1,2,3) (BD Biosciences), followed by incubation of streptavidin–peroxidase polymer (Sigma) and then TMB substrate (Sigma). The resulting OD 655s were found to parallel the concentrations of standard IgG lambda (data not shown). ELISA was also used to examine if there was NC1-specific IgA in the sera. The protocol was the same as that for light-chain ELISA. The secondary antibody used was biotin anti-mouse IgA (1 : 1000 dilution, eBioscience). The function of the secondary antibody was validated using a sandwich method: the plate was coated with unlabelled monoclonal rat anti-mouse IgA (BD Biosciences), followed by purified standard mouse IgA kappa (BD Biosciences) in serial dilutions, then by biotin anti-mouse IgA (eBioscience), followed by incubation of streptavidin–peroxidase polymer (Sigma) and then substrate TMB. The resulting OD 655s were determined to parallel the concentrations of standard IgA kappa (data not shown). All reactions or incubations except plate coating were performed for 30 min at 37°C.

Immunofluorescence microscopy

In order to confirm that the NC1 recombinant protein generated is indeed a skin basement membrane protein, we tested rat pre- and post-immune sera by indirect immunofluorescence microscopy. Pre-immune serum and post-immune serum were each diluted (1 : 20) in 1% BSA in PBS and placed onto the normal SKH1 mouse skin section (8 µm thick) for 45 min. After washing, the slides were then incubated with Alexa Fluor 488-labelled goat anti-rat IgG antibodies (1 : 1000 dilution, Invitrogen) for another 45 min. After washing, the slides were then covered with a mounting medium (glycerol: PBS; 1 : 1; vol : vol) and cover slip, and examined under an Olympus BX60 fluorescence microscope equipped with epi-illumination (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). To demonstrate that NC1 IgG autoantibodies that were induced by immunization did bind to skin basement membrane, direct immunofluorescence microscopy was performed as follows: 8-µm thick frozen sections cut from randomly obtained skin from the three groups of mice were blocked for 30 min by 5% normal goat serum in PBS, and were then exposed to FITC-labelled goat anti-mouse IgG antibodies (Sigma) diluted in 1% BSA in PBS for 45 min. After washing, the slides were mounted and examined as described above. To demonstrate that NC1 autoantibodies reacted with the skin basement membrane, tissue samples from normal SKH-1 mouse skin were fixed with 37°C 3·7% formaldehyde, methanol free (Ultra Pure, Polysciences, Warrington, PA, USA) for 15 min at room temperature. Sections were permealized in 0·2% Triton X-100 for 5 min. Next, tissues were blocked with 10% normal goat serum in PBS for 30 min. Tissues were then incubated with Image-iT FX Signal Enhancer (Invitrogen) for 30 min. Mouse sera from the three experimental groups were diluted (1 : 200) and incubated on the tissue for 45 min. Finally, tissues were incubated with Alexa Fluor 488-labelled goat anti-mouse IgG (Invitrogen) diluted to 1 : 2000 for 45 min. The sections were examined by fluorescence microscope as described above. All steps with antibody or serum incubation were performed in a moist chamber at room temperature.

Western blotting assays

Recombinant mouse NC1 was loaded onto each of the slots on a 4–20% Tris-glycine gradient gel (Invitrogen). After separation, part of the gel was stained by Coomassie blue. The proteins on the rest of the gel were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). After blocking with a blocking buffer (Li-Cor, Lincoln, NE, USA), the membrane was incubated with mouse anti-V5 epitope (1 : 5000), rat post-immune serum (1 : 5000) or rat pre-immune serum (1 : 5000) overnight at 4°C. After washing the nitrocellulose membrane strips were then exposed to Alexa Fluor 680-labelled goat anti-mouse IgG (Invitrogen) or Alexa Fluor 680-labelled goat anti-rat IgG (1 : 5000 Invitrogen) for 1 h at room temperature. The membrane strips and Coomassie blue-stained gel were then scanned by an Odyssey infrared scanner (Li-Cor). Western blot was also used to confirm the IgG autoantibodies detected by ELISA. Briefly, 300 ng of recombinant mouse NC1 protein was loaded onto each of the slots in the gel used above. The membrane strips were incubated with post-immune mouse sera diluted (1 : 10 000), then exposed to Alexa Fluor 680-labelled goat anti-mouse IgG (Invitrogen) diluted (1 : 5000). After washing, the membrane strips were scanned as described above.

Statistical analysis

Significant differences between the two groups were determined by Student's t-test. All analyses were performed by GraphPad Instat Software (San Diego, CA, USA). A P-value < 0·05 was considered significantly different.

Results

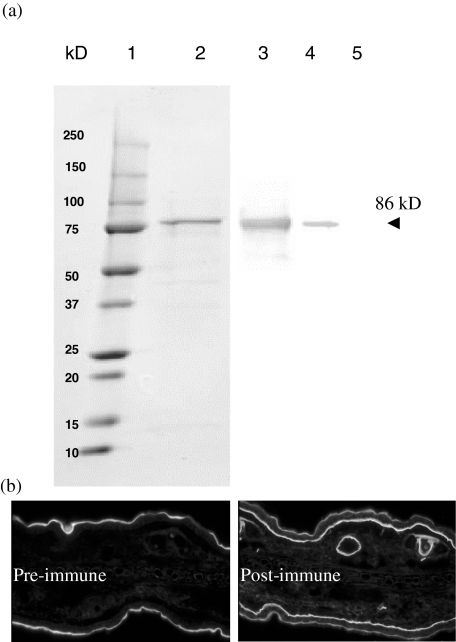

Generation of mouse recombinant NC1 and polyclonal antibody against NC1

From the mouse skin total RNA, we cloned part of NC1 domain of collagen VII. The mouse NC1 cDNA clone contains 1740 base pairs (bp) of nucleotides (from coding nucleotide no. 10 at the 5′ end to nucleotide no. 1749 at the 3′ end based on the DNA sequence in GenBank U32107), encoding 580 amino acids [24,25]. The PCR product contains all the N-terminal amino acids except the first three. The size of recombinant protein expressed in Escherichia coli was approximately 86 kD (Fig. 2a, lane 2, visualized by Coomassie blue) including 16 kD HP-thioredoxin at N-terminal and V5 epitope/6 × histotine at the C-terminus. This 86-kD protein was identified by antibody against V5 epitope (Fig. 2a, lane 3) as well as polyclonal antibodies in rat post-immune serum against this protein (Fig. 2a, lane 4) by Western blot, whereas the pre-immune rat serum did not recognize NC1 recombinant protein (Fig. 2a, lane 5). Indirect immunofluorescence microscope was utilized to further confirm that the antibodies in the rat serum actually reacted with skin basement membrane protein. As illustrated in Fig. 2b, the pre-immune serum (left panel) did not label the skin basement membrane, whereas the post-immune serum (right panel) strongly labelled the skin basement membrane as well as the basement membrane of the hair follicle, confirming that the recombinant mouse type VII collagen NC1 protein that we generated is, indeed, a skin basement membrane protein and is able to induce a strong immune response. Serum from another immunized rat had a similar response against NC1 (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

Generation of recombinant mouse type VII collagen NC1 domain and polyclonal antibodies against mouse NC1. (a). The cDNA of mouse NC1 domain encoding 580 amino acids at the N-terminal was cloned and expressed in Escherichia coli with a molecular mass of approximately 86 kD (lane 2, Coomassie blue-stained). The recombinant protein has a V5 epitope which is used for identifying the correct recombinant protein production by antibody to V5 (lane 3). The serum from the purified NC1 recombinant protein-immunized rat reacts specifically with NC1 (lane 4), while pre-immune serum (same dilution) of the same rat does not react with the protein (lane 5); 2·4 µg, 1·2 µg, 0·12 µg and 0·12 µg recombinant NC1 were loaded to lanes 2, 3, 4 and 5, respectively. (b). The serum from the purified NC1 recombinant protein-immunized rat also reacts distinctively with skin basement membrane zone of the dermal–epidermal junction and hair follicles (right panel), but the pre-immune serum of the same rat does not label it (left panel).

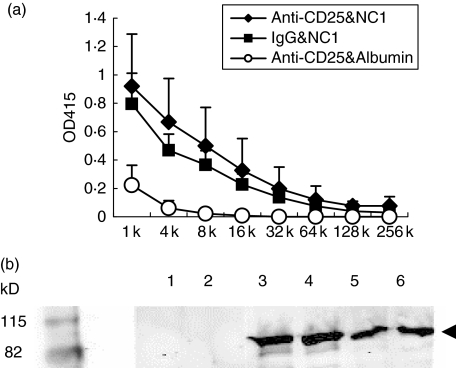

SKH1 mice develop autoantibody against NC1 independent of Treg

Having generated and confirmed a mouse recombinant type VII collagen protein NC1 and demonstrated the effect of anti-CD25 in depleting Treg, we then tested the ability of self antigen mouse NC1 to induce autoimmune response in the presence or absence of Treg. As shown in Fig. 3a, regardless of whether mice received Treg depleting antibody or isotype control, they developed strong IgG class autoantibodies to the recombinant protein. The average titres of the IgG anti-NC1 autoantibodies in mice that received anti-CD25 treatment were slightly higher than in those mice that received isotype control, but no significant difference was observed (P > 0·05). The autoimmune responses are titratable from 1 : 1000 to 1 : 32 000 (Table 1). The mice immunized with mouse albumin and treated with anti-mouse CD25 did not develop IgG class autoantibodies to NC1 (Fig. 3a). The specific reaction of the antoantibodies to NC1 was confirmed further by Western blot. As demonstrated in Fig. 3b, sera from NC1 immunized mice with either Treg depleted (lanes 3 and 4) or undepleted (lanes 5 and 6) had a strong reaction with recombinant protein compared to sera immunized with albumin (lanes 1 and 2). Anti-NC1-specific IgA in the sera of all three groups of mice were undetectable (data not shown).

Fig. 3.

NC1-immunized SKH1 mice produce IgG antoantibodies specifically against recombinant NC1 protein. (a). Titratable enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) titres of autoantibodies. Three groups of female SKH1 mice were included. One group received rat anti-CD25 and mouse NC1 (n = 5, solid diamond), the second group received rat isotype and mouse NC1 (n = 5, solid square) and the third group received rat anti-CD25 and mouse albumin (n = 3, open circle). Mice sera were collected at the end of 5·5 months after the initial immunization and tested for the specific IgG against mouse NC1 by ELISA as described in Materials and methods. (b). Western blot analysis of NC1-specific autoantibodies. Two representative samples from each group are shown: mice treated with anti-CD25 and immunized with albumin (lanes 1 and 2); mice treated with anti-CD25 and immunized with NC1 (lanes 3 and 4); mice treated with rat IgG and immunized with NC1 (lanes 5 and 6). Each of the wells were loaded with 300 ng of recombinant mouse NC1 protein.

Table 1.

Titres of anti-NC1 autoantibodies in the serum.

| Mouse | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | Average |

| Anti-CD25 and NC | 16 000 | 32 000 | 8000 | 4000 | 4000 | 12 800 |

| Isotype and NC1 | 8 000 | 8 000 | 1000 | 8000 | 8000 | 6 600 |

Mice sera were titrated for IgG against NC1 recombinant protein by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay as described in Material and methods. The cut-off OD 415 is 0.36, which is highest in mice receiving anti-CD25 and albumin.

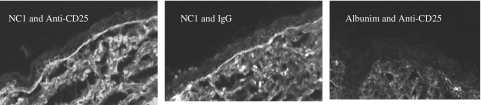

Autoantibody IgG against NC1 reacts with skin basement membrane in vitro and deposits on basement membrane in vivo

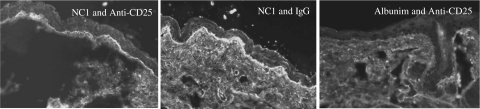

For the IgG anti-NC1 autoantibodies produced by the immunized mice to be pathogenic, they must be able to bind to NC1 in the skin basement membrane. To demonstrate that these NC1 autoantibodies detected by ELISA and Western blotting did bind to the skin basement membrane, indirect immunofluorescence microscopy was performed. As shown in Fig. 4, sera from the mice immunized with mouse recombinant NC1 protein, regardless of their Treg status, react strongly with the basement membrane zone (left and middle panels), whereas the mice immunized with mouse albumin did not react with it (right panel). Furthermore, direct immunofluorescence microscopy was used to determine if autoantibodies against NC1 deposited in the skin basement membrane zone in vivo. As delineated in Fig. 5, similar to the above results, the mice immunized with mouse recombinant NC1 protein with or without anti-CD25 treatment had IgG deposition at the skin basement membrane zone (left and middle panels), whereas the mice immunized with mouse albumin did not have any IgG deposition at the skin basement membrane (right panel).

Fig. 4.

NC1-immunized SKH1 mice produce IgG autoantibodies which react specifically with skin basement membrane. Indirect immunofluorescence microscopy was used to examine the reactivity of autoreactive IgGs with the skin basement membrane zone component, as described in Materials and methods. Left and middle panels show IgG autoantibodies reacting with the skin basement membrane in mice immunized with NC1 in combinations of anti-CD25 or isotype control, respectively. The right panel shows the result of the serum from mouse treated with anti-CD25 and immunized with albumin. Images are representative for each group (original magnification ×40).

Fig. 5.

IgG class autoantibodies deposited to skin basement membrane in NC1-immunized mice. Direct immunofluorescence microscopy was performed to examine the deposit of IgG skin basement membrane zone, as described in Materials and methods. The left panel shows IgG deposits in mice treated with anti-CD25 and immunized with NC1, the middle panel shows IgG deposits in mice treated with rat IgG and immunized with NC1 and the right panel shows IgG deposits in mice treated with anti-CD25 and immunized with albumin. Images are representative for each group (original magnification ×40).

IgG1 and IgG2 subclasses and kappa light chain predominate the anti-NC1 autoantibodies

The subclasses of specific IgG antibodies (IgG1, IgG2a, IgG2b and IgG3) against NC1 were determined by ELISA. As illustrated in Table 2, IgG1, IgG2a and IgG2b together predominate the anti-NC1 autoantibody subclasses. Furthermore, these antibodies seemed to use kappa light chain exclusively in the autoimmune response (Table 2).

Table 2.

Anti-NC1 IgG subclasses and light chains [enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)].

| OD 405 | OD 655 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Groups/no. of mice | IgG1 | IgG2a | IgG2b | IgG3 | Kappa | Lamda |

| Anti-CD25 and albumin | ||||||

| 1 | 0·12 | 0·04 | 0·00 | 0·01 | 0·00 | 0·00 |

| 2 | 0·18 | 0·07 | 0·01 | 0·03 | 0·00 | 0·00 |

| 3 | 0·20 | 0·20 | 0·02 | 0·02 | 0·00 | 0·00 |

| Anti-CD25 and NC1 | ||||||

| 1 | 1·60 | 0·16 | 4·23 | 0·04 | 0·91 | 0·00 |

| 2 | 5·38 | 1·14 | 3·26 | 0·09 | 0·74 | 0·00 |

| 3 | 1·91 | 1·10 | 1·31 | 0·06 | 0·51 | 0·00 |

| 4 | 1·45 | 1·44 | 0·68 | 0·05 | 0·21 | 0·00 |

| 5 | 1·56 | 0·65 | 1·03 | 0·04 | 0·33 | 0·00 |

| IgG and NC1 | ||||||

| 1 | 2·41 | 1·04 | 0·93 | 0·07 | 0·51 | 0·00 |

| 2 | 1·44 | 1·51 | 1·11 | 0·24 | 0·51 | 0·00 |

| 3 | 1·56 | 0·82 | 0·37 | 0·05 | 0·18 | 0·00 |

| 4 | 3·42 | 1·98 | 1·98 | 0·09 | 0·58 | 0·00 |

| 5 | 1·68 | 1·24 | 0·72 | 0·07 | 0·38 | 0·00 |

Mice sera were examined for subclasses and light chains of IgG autoantibodies against NC1 by ELISA as depicted in Materials and methods. Data shown are the original OD values of the ELISAs. The positive cut-off point is 0·20. Positive results are shown in bold type.

Discussion

In the current study, we have demonstrated that autoimmunity against type VII collagen NC1 domain, the major antigenic region of the protein targeted by human patients' autoantibodies, is independent of Treg function through depleting its CD25 surface expression. What does this mean immunologically? One possibility is that the surface CD25 proteins in Treg in SKH1 mice are not functionally active in suppressing autoimmune reactions to type VII collagen, thus contributing to the identical results in mouse groups treated with anti-CD25 and isotype control. Future study of identical experiments in mice of different strains will help to delineate this potential factor. The second possibility is that autoimmune reactions to type VII collagen in SKH1 mice is directly through the activation of autoreactive B cells, thus bypassing T cell regulation. Future study of type VII collagen-autoreactive T cells in the SKH1 mice immunized with NC1 protein may help to determine this point. The third possible explanation is that by immunizing the mice with large doses of immunogen (type VII collagen) in our experiment, which provides a much higher antigen load than that of self protein exposure under a natural condition, the Treg may be overwhelmed by the antigenic dose and not be able to suppress the autoreactivity entirely, allowing some autoreacative T cells to escape suppression by Treg.

In this paper we have reported the successful induction of an autoimmune response to type VII collagen in mice. The type VII collagen-immunized mice, but not the other self protein (albumin)-immunized mice, developed a strong IgG autoantibody response to the type VII collagen. Furthermore, the IgG autoantibodies induced by type VII collagen-immunization were capable of binding to the skin basement membrane in vivo. The subclasses of these autoantibodies, consisting primarily of IgG1, IgG2a and IgG2b, suggest that both Th1 and Th2 helper T cells might have been involved in the production of these anti-NC1 autoantibodies, as IgG1 is influenced substantially by Th2 whereas IgG2a is influenced heavily by Th1 helper T cells [29–32]. The essentially absent IgG3 autoantibody is of interest and may be due to the strong presence of interferon (IFN)-γ and IL-4, hindering the IgG3 subclass switching [29]. Unlike the human immune system, which has approximately 40% of immunoglobulins carrying the lambda light chain, in mice, kappa chain-containing antibodies are approximately 10 times more abundant than lambda chain-containing antibodies [33]. Because the overwhelming majority of antibodies in the mouse system possess kappa light chain, the significance of this predominance in the anti-NC1 autoantibodies in our experiment is not yet clear.

There are several possible explanations for the lack of clinical blister development in our immunized mice. The first is that we simply did not have sufficient observation time for the blister to develop. In human patients with EBA, trauma, as well as IgG autoantibodies that bound to the skin basement membrane, are commonly acknowledged to be contributing factors in the clinical blister formation [1,2]. Thus, it seems that the development of IgG autoantibodies to type VII collagen and the binding of these IgG autoantibodies to the skin basement membrane may not be sufficient for the blistering phenotype to develop in human patients with EBA. Long-term observation after mice develop an autoimmune response to type VII collagen may be needed to monitor the blistering phenotype development. The experiment described in this paper does not allow long-term monitoring because of the substantial ascites which occurred in these mice secondary to administration of anti-CD25 antibodies. Having learned that the autoimmune responses in these mice are independent of Treg, we now can move forward to perform NC1 immunization without the need for anti-CD25 antibodies, thus allowing a longer period of time to monitor for development of the blistering phenotype.

The second possibility is that the immunogen we used did not include a critical pathogenic epitope. This is possible, as our immunogen does not include the entire NC1 domain of the type VII collagen. To explore this possibility, we are currently generating a recombinant mouse protein for the remaining NC1 domain (on the C-terminal portion of the NC1). This additional NC1 protein, along with the NC1 protein already used in this experiment, will be utilized to immunize the mice and their blister development will be monitored.

The third possibility is that the SKH1 strain of mice is resistant to disease development for reasons that have not yet been delineated. To explore this possible explanation, we are currently immunizing other strains of mice, including BALB/c and SJL/j strains, with the same immunogens and will observe whether blisters develop in these additional strains of mice.

In our model system, we found that the autoimmune responses to NC1 self protein was restricted to IgG class, although in human patients with EBA IgA class autoantibodies have been detected. This is interesting, as both Th1 and Th2 helper T cells were probably involved in the class-switching process in our model system due to the fact that both IgG1 and IgG2a class autoantibodies were detected. At least our model system reinforces the findings in human patients, that the predominant autoimmune response to this basement membrane component is through the IgG class humoral immune responses. However, additional studies in different strains of mice may help us to delineate whether the IgG predominance holds true [26–28].

Acknowledgments

This work is supported in part by NIH grant (R01 AR47667, L. S. C).

References

- 1.Woodley DT, Briggaman RA, O’Keefe EJ, Inman AO, Queen LL, Gammon WR. Identification of the skin basement-membrane autoantigen in epidermolysis bullosa acquisita. N Engl J Med. 1984;310:1007–13. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198404193101602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yancey KB. The pathophysiology of autoimmune blistering diseases. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:825–8. doi: 10.1172/JCI24855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen M, Chan LS, Cai X, O'Toole EA, Sample JC, Woodley DT. Development of an ELISA for rapid detection of anti-type VII collagen autoantibodies in epidermolysis bullosa acquisita. J Invest Dermatol. 1997;108:68–72. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12285634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen M, Keene DR, Costa FK, Tahk SH, Woodley DT. The carboxyl terminus of type VII collagen mediates antiparallel dimer formation and constitutes a new antigenic epitope for epidermolysis bullosa acquisita autoantibodies. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:21649–55. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100180200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lapiere JC, Woodley DT, Parente MG, et al. Epitope mapping of type VII collagen. Identification of discrete peptide sequences recognized by sera from patients with acquired epidermolysis bullosa. J Clin Invest. 1993;92:1831–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI116774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jones DA, Hunt SW, III, Prisayanh PS, Briggaman RA, Gammon WR. Immunodominant autoepitopes of type VII collagen are short, paired peptide sequences within the fibronectin type III homology region of the noncollagenous (NC1) domain. J Invest Dermatol. 1995;104:231–5. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12612780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gammon WR, Briggaman RA. Bullous SLE: a phenotypically distinctive but immunologically heterogeneous bullous disorder. J Invest Dermatol. 1993;100:S28–34. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12355210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Woodley DT, Chang C, Saadat P, Ram R, Liu Z, Chen M. Evidence that anti-type VII collagen antibodies are pathogenic and responsible for the clinical, histological, and immunological features of epidermolysis bullosa acquisita. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;124:958–64. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2005.23702.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sitaru C, Mihai S, Otto C, et al. Induction of dermal–epidermal separation in mice by passive transfer of antibodies specific to type VII collagen. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:870–8. doi: 10.1172/JCI21386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gammon WR, Briggaman RA, Woodley DT, Heald PW, Wheeler CE., Jr Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita − a pemphigoid-like disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;11:820–32. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(84)80459-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vodegel RM, de Jong MC, Pas HH, Jonkman MF. IgA-mediated epidermolysis bullosa acquisita: two cases and review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:919–25. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2002.125079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bernard P, Vaillant L, Labeille B, et al. Incidence and distribution of subepidermal autoimmune bullous skin diseases in three French regions. Arch Dermatol. 1995;131:48–52. Bullous Disease French Study Group. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chan LS. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita. In: Lebwohl MG, Heymann WR, Berth-Jones J, Coulson I, editors. Treatment of skin diseases: comprehensive therapeutic strategies. 3. Philadelphia: Mosby; 2006. pp. 191–3. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sakaguchi S, Sakaguchi N, Shimizu J, et al. Immunologic tolerance maintained by CD25+ CD4+ regulatory T cells: their common role in controlling autoimmunity, tumor immunity, and transplantation tolerance. Immunol Rev. 2001;182:18–32. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2001.1820102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen Z, Herman AE, Matos M, Mathis D, Benoist C. Where CD4+CD25+ T reg cells impinge on autoimmune diabetes. J Exp Med. 2005;202:1387–97. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reddy J, Waldner H, Zhang X, et al. Cutting edge: CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells contribute to gender differences in susceptibility to experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol. 2005;175:5591–5. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.9.5591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee JH, Wang LC, Lin YT, Yang YH, Lin DT, Chiang BL. Inverse correlation between CD4 regulatory T-cell population and autoantibody levels in paediatric patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Immunology. 2006;117:280–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2005.02306.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miyara M, Amoura Z, Parizot C, et al. Global natural regulatory T cell depletion in active systemic lupus erythematosus. J Immunol. 2005;175:8392–400. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.12.8392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Veldman C, Hohne A, Dieckmann D, Schuler G, Hertl M. Type I regulatory T cells specific for desmoglein 3 are more frequently detected in healthy individuals than in patients with pemphigus vulgaris. J Immunol. 2004;172:6468–75. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.10.6468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wei WZ, Jacob JB, Zielinski JF, JC, et al. Concurrent induction of antitumor immunity and autoimmune thyroiditis in CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cell-depleted mice. Cancer Res. 2005;65:8471–8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stephens LA, Gray D, Anderton SM. CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells limit the risk of autoimmune disease arising from T cell receptor crossreactivity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:17418–23. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507454102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.DiPaolo RJ, Glass DD, Bijwaard KE, Shevach EM. CD4+CD25+ T cells prevent the development of organ-specific autoimmune disease by inhibiting the differentiation of autoreactive effector T cells. J Immunol. 2005;175:7135–42. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.11.7135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kohm AP, McMahon JS, Podojil JR, et al. Cutting edge: anti-CD25 monoclonal antibody injection results in the functional inactivation, not depletion, of CD4+CD25+ T regulatory cells. J Immunol. 2006;176:3301–5. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.6.3301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li K, Christiano AM, Copeland NG, et al. cDNA cloning and chromosomal mapping of the mouse type VII collagen gene (Col7a1): evidence for rapid evolutionary divergence of the gene. Genomics. 1993;16:733–9. doi: 10.1006/geno.1993.1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kivirikko S, Li K, Christiano AM, Uitto J. Cloning of mouse type VII collagen reveals evolutionary conservation of functional protein domains and genomic organization. J Invest Dermatol. 1996;106:1300–6. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12349019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khattri R, Cox T, Yasayko SA, Ramsdell F. An essential role for Scurfin in CD4+CD25+ T regulatory cells. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:337–42. doi: 10.1038/ni909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hori S, Nomura T, Sakaguchi S. Control of regulatory T cell development by the transcription factor Foxp3. Science. 2003;299:1057–61. doi: 10.1126/science.1079490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fontenot JD, Gavin MA, Rudensky AY. Foxp3 programs the development and function of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:330–6. doi: 10.1038/ni904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Deenick EK, Hasbold J, Hodgkin PD. Decision criteria for resolving isotype switching conflicts by B cells. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:2949–55. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Coffman RL, Lebman DA, Rothman P. Mechanism and regulation of immunoglobulin isotype switching. Adv Immunol. 1993;54:229–70. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60536-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Snapper CM, Mond JJ. Towards a comprehensive view of immunoglobulin class switching. Immunol Today. 1993;14:15–17. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(93)90318-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hasbold J, Hong JS, Kehry MR, Hodgkin PD. Integrating signals from IFN-gamma and IL-4 by B cells: positive and negative effects on CD40 ligand-induced proliferation, survival, and division-linked isotype switching to IgG1, IgE, and IgG2a. J Immunol. 1999;163:4175–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Abbas AK, Lichtman AH. Antibodies and antigens: cellular and molecular immunology. 5. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2002. pp. 54–5. [Google Scholar]