Abstract

Summary

The NOD/SCID mouse model is one of the most established model systems for the analysis of human stem cells in vivo. The lack of mature B and T cells renders NOD/SCID mice susceptible to transplantable human stem and progenitor cells. One remaining functional component of the immune system in NOD/SCID mice is natural killer (NK) cells. We rationalized that by eliminating NK cell-mediated cytotoxicity in this model system engraftment of human haematopoietic stem cells could be improved. Thus perforin-deficient NOD/SCID mice (PNOD/SCID) were generated, which display a complete lack of NK cell-mediated cytotoxicity. To test the engraftment potential of human stem cells in PNOD/SCID mice, we compared the repopulating potential of human haematopoietic stem cells in these mice with the repopulating potential in NOD/SCID mice. Upon injection with varying numbers of mononuclear cells from human cord blood, the number of engrafted PNOD/SCID mice was lower (34·8%) than the number of engrafted NOD/SCID mice (64·7%). Similarly, injection of purified CD34+ human cord blood cells led to engraftment in 32·3% PNOD/SCID versus 60% in NOD/SCID mice. Surprisingly, these results show that the inactivation of cytotoxic activity of NK cells in PNOD/SCID mice did not result in better engraftment with human haematopoietic stem cells. A potential reason for this observation could be that compensatory activation of NK cells in PNOD/SCID mice induces high levels of soluble factors resulting in an environment unfavourable for human stem cell engraftment.

Keywords: human hematopoietic engraftment, NK-cell-mediated cytotoxicity, perforin, transplant rejection, xenotransplantation

Introduction

Immunodeficient mouse models were established originally as in vivo models to analyse immunoregulatory processes and to elucidate the pathogenesis of autoimmune disorders [1]. In addition, immunodeficient mice are used as recipients in xenotransplantation experiments to study growth and behaviour of lymphoid tumours in vivo [2]. They are also used widely to study engraftment and differentiation of allogeneic and xenogeneic transplants [3,4].

Bosma et al. developed a mouse strain termed the severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) mouse which has an autosomal recessive mutation in the scid gene. This results in unsuccessful DNA rearrangement and prevents productive rearrangement of immunoglobulin and T cell receptor genes. The effect is a lack of functional lymphocytes and results in a deficiency of immune functions that are mediated by T and B-cells [1,5–7]. These mice are an ideal in vivo model for the human SCID disorder. Furthermore, these immunodeficiencies also made this mouse strain an ideal model system for xenotransplantation experiments with human haematopoietic transplants. SCID mice were used in three different ways to investigate the engraftment of human haematopoietic stem cells. The first model described was the SCID-hu model. In this system, human fetal liver or fetal bone marrow was transplanted together with fetal thymus tissue under the renal capsule of a non-irradiated SCID mouse [8]. The idea of this technique was to provide the transplanted stem cells with a human microenvironment created by the human fetal thymus tissue. In a second model, normal mice were first irradiated lethally, transplanted with bone marrow cells of SCID mice and subsequently transplanted with human bone marrow cells [9].

The third and most applied variant of the SCID mouse model is the intravenous injection of stem cells into sublethally irradiated recipients. Lapidot et al. first described this method in 1992, where the recipient SCID mice were irradiated with 375–400 cGy prior to the transplantation of human stem cells. A problem of this SCID mouse model is the low level of human engraftment, which ranged from 0·5% to 5% [10]. There are at least two potential reasons accounting for this low engraftment. First, haematopoietic stem cells need special cytokines for proliferation and differentiation. It is very likely that the cytokines produced by the murine microenvironment were not sufficient to fulfil this function due to a lack of species cross-activity of these cytokines. The second explanation for the low engraftment could be a compensatory enhanced activity of the innate immune resistance in these SCID mice. Although SCID mice have no functional T and B cells, their granulocyte and macrophage function is normal. Furthermore, it could be shown that SCID mice have elevated levels of haemolytic complement and natural killer (NK) cell activity, which might disturb or suppress human stem cell growth during the engraftment process [11].

In 1994 Shultz and coworkers introduced an improved mouse strain, which was produced by back-crossing the SCID mutation with the NOD/Lt (non-obese diabetic) strain background [11]. The NOD/Lt mouse strain is a model organism for insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (IDDM) that is mediated by T cells. These mice display a functional deficit in NK cells as well as an absence of circulating complement [12–14]. The new NOD/LtSz-scid mouse (usually called NOD/SCID) combined the immunodeficiencies of the two parental strains: the lack of lymphoid cells in the SCID mouse and the defects in the innate immunity of the NOD/Lt mouse. In addition these mice are not affected by diabetes because they lack the T cells which are necessary to mediate the disease. In fact, engraftment of human haematopoietic cells in those mice was much more efficient compared to SCID mice even without the application of human growth factors [15].

Today the NOD/SCID mouse model is one of the most established and applied immune-deficient mouse model systems for the transplantation of human haematopoietic stem cells. The lack of a functional immune system renders NOD/SCID mice susceptible to transplantable human stem and progenitor cells recovered from umbilical cord blood, fetal liver or bone marrow. Engraftment of human SCID-repopulating cells (SRC) can be found in spleen, blood and bone marrow. Human haematopoietic cells found after 6–8 weeks in bone marrow of engrafted NOD/SCID mice are comprised of early progenitors as well as differentiated cells of the lymphoid and myeloid lineage. However, a complete multi-lineage differentiation including T cells has not been shown in this mouse strain.

One of the few remaining functional components of the immune system in NOD/SCID mice is NK cells. NK cells eliminate target cells with a low or missing expression of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I antigens [16]. Kumar et al. showed that the rejection of parental bone marrow cells by individuals of the F1 generation is mediated by NK cells [17]. This effect, usually called hybrid resistance, indicates that repopulating bone marrow cells are potential targets cells for NK cells. Therefore it is possible that the remaining NK activity in NOD/SCID mice impairs or prevents the survival of early, immature human haematopoietic stem cells. Kägi et al. demonstrated in experiments with perforin-deficient mice that the immunity mediated by NK cells is dependent on the perforin pathway [18,19]. After the binding of the NK cell to the target cell, the NK cell releases perforin from its cytotoxic granules. The perforin polymerizes and generates pores in the membrane of the target cell [18]. In perforin-deficient mice, normal levels of CD8+ and NK cells can be found but NK-mediated cytotoxicity is completely absent. In these mice NK cells can still be activated, but the activated NK cells cannot release perforin. Therefore, the killing mechanism of NK cells is eliminated in these mice.

It is expected that a combination of NOD/SCID and perforin defects would increase the immune defect and should allow for improved engraftment of human stem cells. In this study we report on the generation and characterization of a combined perforin-deficient NOD/SCID mouse (PNOD/SCID) by crossing perforin knock-out NOD mice (PNOD) with NOD/SCID mice. Compared to normal NOD/SCID mice, whose NK cell cytotoxic activity is low but still detectable, the new PNOD/SCID mice display a complete lack of NK cell-mediated cytotoxic activity. In transplantation experiments human engraftment of mononuclear and CD34+ cord blood cells was compared in PNOD/SCID mice and in NOD/SCID mice. Surprisingly, engraftment incidence and levels of engraftment were significantly lower in PNOD/SCID than in NOD/SCID mice.

Materials and methods

Human cells

Mononuclear cells (MNC) were obtained from discarded umbilical cord blood (UCB) samples by density gradient centrifugation using Biocoll separating solution (Biochrom AG, Berlin, Germany). CD34+ cells were obtained by double selection with MACS columns using the CD34 Progenitor Isolation Kit (Miltenyi Biotech, Bergisch-Gladbach, Germany). Selection was performed as recommended by the manufacturer. Purity was checked by flow cytometry. Cells for injection were resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) Dulbecco’s minimum essential medium (DMEM) (gibco, Paisley, Scotland, UK) and injected in 400–800 µl volume per mouse. For some experiments CD34+ cells from two cord blood samples were pooled to obtain sufficient numbers of progenitor cells. In some experiments CD34+ cells were cryopreserved after separation in PBS DMEM containing 8% human albumin (Baxter, Unterschleißheim, Germany), 15% dimethyl sulphoxide (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) and 20 U/ml Liquemin (Roche, Grenzach-Wyhlen, Germany). Prior to injection, frozen cells were thawed, washed in PBS DMEM, counted and resuspended in PBS DMEM.

Development and maintenance of mice

NOD/LtSz-scid/scid (NOD/SCID) mice were bred from breeding pairs obtained originally from D. Shultz (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME, USA) at the Ontario Cancer Institute (Toronto, ON, Canada). Perforin-deficient NOD mice (PNOD) were bred by D. Kägi as described in Kägi et al. [20]. C57/BL6 mice were originally bought from Elevage Janvier (Orleans, France).

To produce perforin-deficient NOD/SCID mice (PNOD/SCID), NOD/SCID mice were crossed with PNOD mice. Mice carrying the SCID defect were identified by their lack of B and T cells shown by fluorescence activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis for the markers CD3, CD4, CD8 and B220. In the following breedings only mice deficient in B and T cells were used. The perforin genotype was determined by PCR.

After the generation of PNOD/SCID mice they were transferred to Freiburg, Germany. NOD/SCID, PNOD/SCID and C57/BL6 mice were bred under specific pathogen-free conditions at the ZKF mouse facility of the University Clinic Freiburg, Germany. Mice received autoclaved drinking water supplemented with Borgal (Intervet, Whitby, ON, Canada) and a sterilized mouse diet.

Genotyping of mice

DNA was obtained from tail tips by phenol–chloroform extraction and PCR was performed using the primers with the following sequences to verify perforin knock-out: 5′GCA TCG CCT TCT ATC GCC TTC T-3′, 5′CCG GTC CTG AAC TCC CCA C3′ and 5′AGC CCC TGC ACA CAT TAC TG-3′. Individuals with the mutated allele show a 250-base pairs (bp) product, wild-type individuals a 300-bp product.

Transplantation of cord blood cells

Mice (6–14 weeks old) received a total-body irradiation with a sublethal dose of 375 cGy using a Cs-137 source 4–24 h before transplantation. Mice were killed after 3–6 weeks (when injected with MNC) or 6–13 weeks (when injected with CD34+ cells). Bone marrow (BM) from femora and tibiae were flushed into Alpha-MEM (BioWhittackerEutope, Verviers, Belgium). Spleens were dissected and crushed through a 70-µm cell strainer into Alpha-MEM. Peripheral blood was taken under narcosis with Isofluran (Abbott, Wiesbaden, Germany) from the retro-orbital sinus.

NK cell assay

The cytotoxicity of NK cells was measured using a chromium-release test. Twenty hours before the assay, mice were injected intravenously (i.v.) with 0·1 mg of the NK cell inducer polyinosinic–polycytidylic acid (poly-I:C; Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) in 0·1 ml PBS. Their spleens were used as a source of NK effectors. Cytotoxicity was determined using 51Cr-labelled target cells in a standard 5-h assay as described [21]. As target cells, NK-sensitive YAC-1 and RMA-S cell lines were used [16]. Specific 51Cr release was calculated as [(experimental release − spontaneous release)/(maximum release − spontaneous release)] × 100.

Flow cytometric analysis of murine BM, spleen and peripheral blood cells

To prepare peripheral blood cells collected from the retroorbital sinus under narcosis with Forene (Abbott, Wiesbaden, Germany) for flow cytometry, red cells were lysed with an 8% ammonium chloride solution and remaining mononuclear cells were resuspended in PBS DMEM. Cells from BM and spleen were also resuspended in PBS DMEM. Cells from all three tissues were incubated with monoclonal antibodies at the concentration recommended by the manufacturer for 20 min at 4°C. Anti-human CD45 antibodies were conjugated to peridinin chlorophyll (PerCP), anti-mouse CD45R/B220 to APC. Anti-human CD3, CD15, CD20, CD34, CD45 and mouse IgG1a were conjugated to FITC and anti-human CD14, CD19, CD33, CD38, anti-mouse CD3, CD49b/PAN-NK cells, rat IgM and mouse IgG2a to phycoerythrin (PE). All antibodies were bought from Pharmingen/Becton Dickinson (San Jose, CA, USA) and Immunotech (Marseille, France). Cells were then washed and resuspended in PBS DMEM and analysed on a Becton Dickinson FacsCalibur. For each experiment, an aliquot of cells was stained with isotype controls. BM cells from an untransplanted PNOD/SCID or NOD/SCID mouse were stained in parallel as an additional negative control.

Quantification of serum IgG

Murine blood was taken from the hearts of 6–8-week-old mice under narcosis with Forene and incubated without anti-coagulant at room temperature for 30 min. The blood samples were then centrifuged for 5 min at 5200 g. The supernatant was collected, transferred to a new tube and stored at −80°C.

Quantitative determination of serum IgGs was performed with the mouse serum IgG enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) Kit from Alpha Diagnostics International (San Antonio, TX, USA), as recommended by the manufacturer.

Haematology

Murine blood was taken from the heart under narcosis with Forene and stored in ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA) tubes.

Blood smears for differential counts were stained with Pappenheim staining. Two hundred randomly chosen white blood cells were counted under the microscope and classified using an AC-8 counter (Hecht, Sondheim, Germany).

Statistics

Mice were classified ‘engrafted’ when the following criteria were fulfilled: (a) when the portion of human CD45+ cells was more than 0·1% and (b) when the living cells gated on CD45 PerCP were positive for a second human marker, for example CD38. Analysis was carried out with either CellQuest or CellQuestPro (Becton Dickinson).

Differences in numbers of engrafted mice were compared using Fisher's exact test. Engraftment levels and cell populations were compared using Wilcoxon's two-sample test. P < 0·05 was considered significant.

Results

In order to obtain an immunodeficient mouse strain that has no functional NK cells in addition to a lack of mature B and T cells, we crossed NOD/SCID mice with PNOD mice. The generated double knock-out PNOD/SCID–/– mice were tested by FACS analyses to detect the deficiency of mature B and T cells, and by PCR to confirm the lack of perforin. No differences in the production of offspring and the lifespan between PNOD/SCID and NOD/SCID were observed.

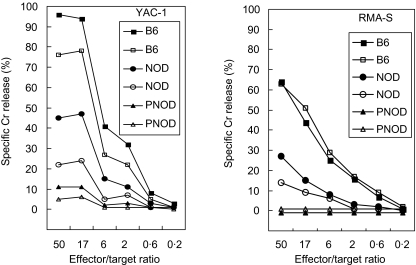

The lytic activity of NK cells from PNOD/SCID mice was tested and compared with NK cells from NOD/SCID and C57/BL6 mice in a NK cell assay using YAC-1 and RMA-S as NK-sensitive target cells (Fig. 1). The results show that target cells were lysed effectively by NK cells from C57/BL6 mice. The effectiveness of NK cells from NOD/SCID mice was reduced by approximately 50% compared to that of NK cells from C57/BL6 mice. In contrast, no lytic activity of NK cells from PNOD/SCID mice could be detected when RMA-S target cells were used. Only a low specific Cr release was detected using YAC-1 cells as target cells. Therefore, NK cell-mediated cytotoxic activity is absent in PNOD/SCID mice.

Fig. 1.

Lack of natural killer cell-mediated cytotoxicity in PNOD/SCID mice. Two animals of each of the three mouse strains C57/BL6 (B6), NOD/SCID (NOD) and PNOD/SCID (PNOD) were injected with 0·1 mg/0·1 ml poly-IC. Splenocytes were isolated 24 h later and used as effector cells in a cytotoxicity assay using 51Cr-labelled YAC-1 and RMA-S cells as targets.

To characterize the haematopoietic system of PNOD/SCID, bone marrow and spleen cells from 6–9-week-old mice were analysed for T cells (CD3), B cells (B220), granulocytes (Gr-1) and NK cells (CD49b/PAN-NK), and compared with corresponding cells from NOD/SCID and C57/BL6 mice. Expression of all four markers was similar in PNOD/SCID and NOD/SCID (Table 1). In contrast to C57/BL6 mice almost no expression of CD3 and B220 could be detected in the spleen of both immunodeficient strains. The percentage of NK cells in PNOD/SCID mice was 1·0% in bone marrow and 1·4% in the spleen. Both values did not differ significantly from that in NOD/SCID and C57/BL6 mice. The percentage of granulocytes was similar in all three strains tested.

Table 1.

Flow cytometry analysis of bone marrow (BM) and spleen cells of C57/BL6, NOD/SCID and PNOD/SCID mice. Data are means of percentages of BM and spleen cells expressing the cell surface markers. Organs of five mice of each mouse strain were analysed.

| Specificity | Organ (%) | C57/BL6 (%) (n = 5) | NOD/SCID (%) (n = 5) | PNOD/SCID (%) (n = 5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD3 | BM | 1·5 ± 0·1 | 1·0 ± 1·0 | 0·6 ± 0·2 |

| Gr-1 | BM | 4·2 ± 0·5 | 8·0 ± 1·7 | 6·7 ± 0·6 |

| B220 | BM | 13·1 ± 3·1 | 0·2 ± 0 | 0·9 ± 0·2 |

| CD49b/PAN-NK | BM | 2·1 ± 0·8 | 1·5 ± 0·5 | 1·0 ± 0·2 |

| CD3 | Spleen | 24·3 ± 5·3 | 0·1 ± 0·1 | 0·1 ± 0·2 |

| Gr-1 | Spleen | 1·7 ± 0·2 | 0·6 ± 0·2 | 0·4 ± 0·2 |

| B220 | Spleen | 23·8 ± 2·9 | 1·2 ± 0·4 | 0·6 ± 0·1 |

| CD49b/PAN-NK | Spleen | 1·6 ± 0·8 | 2·6 ± 2·1 | 1·4 ± 0·4 |

Sera of 6–8-week-old C57/BL6, NOD/SCID and PNOD/SCID mice were assayed for IgG levels. IgG serum concentrations of C57/BL6 mice varied from 0·7 to 6·2 mg/ml. No serum IgGs could be detected in the sera of either PNOD/SCID or NOD/SCID. Therefore no signs of leakiness could be detected in either PNOD/SCID or NOD/SCID mice.

Lymphocytes, neutrophils, eosinophils and monocytes were counted in blood smears of PNOD/SCID, NOD/SCID and C57/BL6 mice. In contrast to the C57/BL6 mice, where lymphocytes were the dominating population of white blood cells (83% on average), the main population of white blood cells in both immunodeficient strains was neutrophils (Table 2). In PNOD/SCID mice, 79% of all white blood cells were neutrophils. There was no difference to NOD/SCID mice where 68·8% of the white blood cells were neutrophils (P = 0·06, Wilcoxon's two-sample test). No significant differences in percentages of lymphocytes (P = 0·09), eosinophils (P = 0·4) and monocytes (P = 0·18) between PNOD/SCID and NOD/SCID mice were detected. In accordance with published earlier work with perforin-deficient mice, we could not detect any evidence that bone marrow functions in PNOD/SCID mice are affected by the lack of perforin [18].

Table 2.

Differential leucocyte counts in C57/BL6, NOD/SCID and PNOD/SCID mice.

| Cell population | C57/BL6 (n = 5) | NOD/SCID (n = 5) | PNOD/SCID (n = 5) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lymphocytes | 83 ± 3·7 | 24·1 ± 6·2 | 16·4 ± 7·8 |

| Monocytes | 3·1 ± 1·7 | 6·1 ± 1·9 | 4·2 ± 2·7 |

| Neutrophils | 13·6 ± 3·3 | 68·8 ± 5·8 | 79 ± 7·0 |

| Eosinophils | 0·3 ± 0·7 | 1·0 ± 1·2 | 0·4 ± 0·8 |

To test the engraftment potential of human stem cells in PNOD/SCID mice, we compared the repopulating potential of stem cells in PNOD/SCID with the repopulating potential in NOD/SCID mice. Groups of sublethally irradiated NOD/SCID and PNOD/SCID mice were injected with equal doses of human haematopoietic cells from umbilical cord blood.

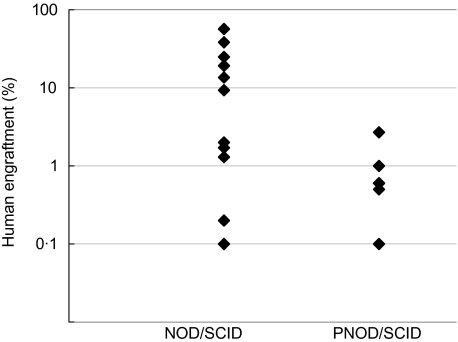

In a first set of experiments we injected either 2·5 × 107 or 3 × 107 unseparated mononuclear cells from umbilical cord blood into both strains. After 3–6 weeks, the murine bone marrow was examined for the presence of human haematopoietic cells by staining with a human-specific CD45 antibody. The frequency of mice engrafted with human haematopoietic stem cells was lower in PNOD/SCID mice compared to NOD/SCID, although it was not significantly different (P = 0·11, Fisher’s exact test). From a total of 23 transplanted PNOD/SCID mice, eight were engrafted compared to 11 of 17 in NOD/SCID (34·8% versus 64·7%; Table 3). The engraftment level varied from 0·1% to 2·7% with a mean engraftment of 0·8% per engrafted mouse in PNOD/SCID. Engraftment levels observed in NOD/SCID mice were between 0·1% and 56·6%, with a mean of 15·2% (Fig. 2). The level of engraftment was significantly lower in PNOD/SCID mice compared to NOD/SCID (P = 0·031, Wilcoxon’s two-sample test).

Table 3.

Human engraftment of CB MNC and CD34+ cells in NOD/SCID and PNOD/SCID mice.

| NOD/SCID | PNOD/SCID | NOD/SCID | PNOD/SCID | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Injected cells | CD34+ | CD34+ | MNC | MNC |

| No. of injected mice | 35 | 34 | 17 | 23 |

| No. of engrafted mice | 21 | 11 | 11 | 8 |

| Portion of engrafted mice (%) | 60 | 32·2 | 64·7 | 34·8 |

Fig. 2.

Engraftment of human mononuclear cord blood cells in PNOD/SCID and NOD/SCID mice. PNOD/SCID and NOD/SCID mice were injected with 2·5 × 106 or 3·0 × 106 mononuclear cells from human cord blood. Mice were killed 3–6 weeks after transplantation. Frequencies of human CD45+ haemopoietic cells in the murine bone marrow were measured by flow cytometry.

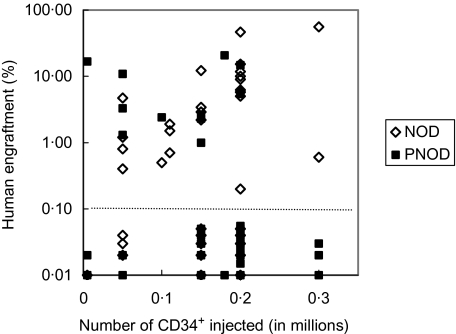

To compare the engraftment potential of haematopoietic progenitors in PNOD/SCID and NOD/SCID, CD34+ cells from umbilical cord blood were isolated by MACS technology. Mice received 5 × 103 to 3 × 104 CD34+ cells. In total, we transplanted 35 NOD/SCID and 34 PNOD/SCID mice with varying numbers of CD34+ cells. Human engraftment was detected in both mouse strains. The frequency of mice engrafted was significantly lower in PNOD/SCID (11 of 34) compared to NOD/SCID (21 of 35; P = 0·03, Fisher's exact test). The level of engraftment varied from 0·2% to 55·6% in NOD/SCID and from 1·0 to 20·7% in PNOD/SCID (Fig. 3). The mean level of engraftment was not significantly different in NOD/SCID (9·5%) compared to PNOD/SCID (6·1%; P = 1, Wilcoxon’s two-sample test).

Fig. 3.

Engraftment of human haemopoietic stem cells in PNOD/SCID and NOD/SCID mice. PNOD/SCID and NOD/SCID mice were injected with varying numbers of CD34+ cells from human cord blood. Mice were killed 6–13 weeks after transplantation. Frequencies of human haemopoietic cells in the murine bone marrow were measured by flow cytometry. The dotted line separates engrafted from not-engrafted mice.

Human cells in the bone marrow of PNOD/SCID and NOD/SCID mice transplanted with CD34+ cord blood cells were analysed for multi-lineage differentiation. Similar levels of early lymphoid cells (CD38), B cells (CD19, CD20), T cells (CD3), myeloid cells (CD14, CD15 and CD33) and CD34+ progenitor cells could be detected. Thus, no differences in the in vivo differentiation pattern of transplanted human haematopoietic stem cells could be detected.

Discussion

NOD/SCID mice are characterized by their deficiency of functional lymphocytes, a functional deficit in NK cells and an absence of circulating complement factors [11–14]. Therefore these mice tolerate xenogeneic transplants and are used widely as in vivo models for the transplantation of human cells [4,22]. Although NK cell function is reduced in NOD/SCID mice the cytotoxic activity of NK cells is still present, and might impair or prevent the survival and engraftment of early, immature human haematopoietic stem and progenitor cells when injected in these mice.

To obtain a strain of NOD/SCID mice with a complete absence of NK cell-mediated cytotoxicity, combined perforin-deficient NOD/SCID mice were produced by crossing PNOD mice with NOD/SCID mice. Compared to normal NOD/SCID mice whose NK cell-mediated cytotoxicity is low but still detectable, the PNOD/SCID mice displayed a complete lack of NK cell-mediated cytotoxicity as determined by NK cell assays.

The newly established PNOD/SCID mouse strain showed no differences in the production of offspring and the lifespan compared to NOD/SCID mice. Percentages of all cell types in the bone marrow and spleen were very similar. Therefore, the absence of perforin had no measurable effect on the haematopoiesis or on stromal cell function in the haematopoietic organs.

In transplantation experiments, human engraftment of mononuclear and CD34+ cord blood cells in the newly established PNOD/SCID was compared to the engraftment in normal NOD/SCID mice. Both engraftment incidence and the level of human engraftment after transplantation with MNC as well as with CD34+ cells were lower in PNOD/SCID than in NOD/SCID mice. These results are surprising, as generation of mice with broadened deficiencies are expected to improve the conditions for cells to survive and/or proliferate in their xenogeneic host. This effect was shown with the generation of the NOD/SCID mouse by combining the immune defects of the NOD/Lt and the SCID mouse [11].

A similar approach to eliminate the activity of NK cells in NOD/SCID mice has been reported by Christianson et al. In their NOD/SCID-beta2-microglobulin-deficient mice, homozygosity for the B2m(null) allele resulted in the absence of MHC class I expression. NOD/SCID-beta2-microglobulin mice have functional NK cells, but NK cells are not activated due to a modulation of NK cell receptors in MHC class I-deficient mice [23]. One effect of this additional defect is an enhanced engraftment potential. An 11-fold higher frequency of SRC compared to normal NOD/SCID mice was observed in these mice [24]. In addition, it was shown that NOD/SCID-beta2 microglobulin-null mice were sequentially engrafted by two distinct and previously unrecognized populations of transplantable human short-term repopulating haematopoietic cells (STRCs). These cells do not engraft normal NOD/SCID mice efficiently [25].

The PNOD/SCID mouse and NOD/SCID-beta2 microglobulin-null mouse share the functional deficiency of NK cells. NK cells from both mouse strains have almost completely lost the lytic activity of their NK cells. The major difference between the PNOD/SCID mouse and the NOD/SCID-beta2-microglobulin-deficient mouse is that NK cells cannot be activated in the latter. It is highly likely that NK cells in NOD/SCID mice are activated by MNC or progenitor cells which are injected into them. In the NOD/SCID-beta2-microglobulin-deficient mouse, the few remaining NK cells cannot be activated and therefore they do not impair human cells during their engraftment, proliferation and differentiation in the mouse environment. The situation in the PNOD/SCID mouse is different. Although NK cells in the PNOD/SCID mouse can no longer kill cells due to their lack of perforin, they can still be activated. It is possible that cytokines or similar molecules released from the activated NK cells, which are unable to kill target cells, may hamper the repopulation of human stem cells. Activation of NK cells in PNOD/SCID mice may induce high levels of soluble factors, resulting in an environment unfavourable for human stem cell engraftment. Therefore, NK cells possibly prevent engraftment in the PNOD/SCID mouse model by non-cytotoxic mechanisms.

Acknowledgments

We thank B. Sauer and E. de Lima-Hahn for technical assistance, Dr S. Whitlow for critical reading and improvements on the manuscript and Professor Dr R. Mertelsmann for his continuing support.

References

- 1.Bosma GC, Custer RP, Bosma MJ. A severe combined immunodeficiency mutation in the mouse. Nature. 1983;301:527–30. doi: 10.1038/301527a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Imada K. Immunodeficient mouse models of lymphoid tumors. Int J Hematol. 2003;77:336–41. doi: 10.1007/BF02982640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bosma MJ, Carroll AM. The SCID mouse mutant: definition, characterisation, and potential uses. Annu Rev Immunol. 1991;9:323–50. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.09.040191.001543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Greiner DL, Hesselton RA, Shultz LD. SCID mouse models of human stem cell engraftment. Stem Cells. 1998;16:166–77. doi: 10.1002/stem.160166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lieber MR, Hesse JE, Lewis S, et al. The defect in murine severe combined immune deficiency: joining of signal sequences but not coding segments in V(D)J recombination. Cell. 1988;55:7–16. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90004-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Malynn BA, Blakwell TK, Fulop GM, et al. The scid defect affects the final step of immunoglobulin VDJ recombinase mechanism. Cell. 1988;54:453–60. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90066-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lapidot T, Fajerman Y, Kollet O. Immune-deficient SCID and NOD/SCID mice models as functional assays for studying normal and malignant human haematopoiesis. J Mol Med. 1997;75:664–73. doi: 10.1007/s001090050150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCune JM, Namikawa R, Kaneshima H, et al. The SCID-hu mouse: murine model for the analysis of human haematolymphoid differentiation and function. Science. 1988;241:1632–9. doi: 10.1126/science.241.4873.1632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lubin I, Faktorowich Y, Lapidot T, et al. Engraftment and development of human T and B cells in mice after bone marrow transplantation. Science. 1991;252:427–31. doi: 10.1126/science.1826797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lapidot T, Pflumio F, Doedens M, et al. Cytokine stimulation of multilineage hematopoiesis from immature human cells engrafted in SCID mice. Science. 1992;255:1137–41. doi: 10.1126/science.1372131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shultz LD, Schweitzer PA, Christianson SW, et al. Multiple defects in innate and adaptive immunologic function in NOD/LtSz-scid mice. J Immunol. 1995;154:180–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kataoka S, Satoh J, Fujiya H, et al. Immunologic aspects of the nonobese diabetic (NOD) mouse: abnormalities of cellular immunity. Diabetes. 1983;32:247. doi: 10.2337/diab.32.3.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Serreze DV, Leiter EH. Defective activation of T suppressor cell function in nonobese diabetic mice: potential relation to cytokine deficiencies. J Immunol. 1988;140:38001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baxter AG, Cooke A. Complement lytic activity has no role in the pathogenesis of autoimmune diabetes in NOD mice. Diabetes. 1993;42:1574. doi: 10.2337/diab.42.11.1574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vormoor J, Lapidot T, Pflumio F, et al. Immature human cord blood progenitors engraft and proliferate to high levels in severe combined immunodeficient mice. Blood. 1994;83:2489–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karre K, Ljunggren HG, Piontek G, et al. Selective rejection of H-2-deficient lymphoma variants suggests alternative immune defence strategy. Nature. 1986;319:675–8. doi: 10.1038/319675a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kumar V, George T, Yu YYL, et al. Role of murine NK cells and their receptors in hybrid resistance. Curr Opin Immunol. 1997;9:52–6. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(97)80158-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kägi D, Ledermann B, Bürki K, et al. Cytotoxicity mediated by T cells and natural killer cells is greatly impaired in perforin-deficient mice. Nature. 1994;369:31–7. doi: 10.1038/369031a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van den Broek MF, Kägi D, Zinkernagel RM, Hengartner H. Perforin dependence of natural killer cell-mediated tumor control in vivo. Eur J Immunol. 1995;25:3514–6. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830251246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kägi D, Odermatt B, Seiler P, et al. Reduced incidence and delayed onset of diabetes in perforin-deficient nonobese diabetic mice. J Exp Med. 1997;186:989–97. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.7.989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cerottini JC, Brunner KT. Cell-mediated cytotoxicity, allograft rejection, and tumor immunity. Adv Immunol. 1974;18:67–132. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60308-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dao MA, Nolta JA. Immunodeficient mice as models of human hematopoietic stem cell engraftment. Curr Opin Immunol. 1999;11:532–7. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(99)00006-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Christianson SW, Greiner DL, Hesselton R, et al. Enhanced human CD4+ T cell engraftment in beta2-microglobulin-deficient NOD-scid mice. J Immunol. 1997;158:3578–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kollet O, Peled A, Byk T, et al. Beta2 microglobulin-deficient (B2m (null)) NOD/SCID mice are excellent recipients for studying human stem cell function. Blood. 2000;95:3102–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Glimm H, Eisterer W, Lee K, et al. Previously undetected human hematopoietic cell populations with short-term repopulating activity selectively engraft NOD/SCID-beta2 microglobulin-null mice. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:199–206. doi: 10.1172/JCI11519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]