Abstract

A calmodulin-like protein (CAMLP) from Mycobacterium smegmatis was purified to homogeneity and partially sequenced; these data were used to produce a full-length clone, whose DNA sequence contained a 55-amino-acid open reading frame. M. smegmatis CAMLP, expressed in Escherichia coli, exhibited properties characteristic of eukaryotic calmodulin: calcium-dependent stimulation of eukaryotic phosphodiesterase, which was inhibited by the calmodulin antagonist trifluoperazine, and reaction with anti-bovine brain calmodulin antibodies. Consistent with the presence of nine acidic amino acids (16%) in M. smegmatis CAMLP, there is one putative calcium-binding domain in this CAMLP, compared to four such domains for eukaryotic calmodulin, reflecting the smaller molecular size (approximately 6 kDa) of M. smegmatis CAMLP. Ultracentrifugation and mass spectral studies excluded the possibility that calcium promotes oligomerization of purified M. smegmatis CAMLP.

Calmodulin, a highly conserved and ubiquitous protein in eukaryotic cells (16, 17), is a small, heat- and acid-stable protein composed of about 155 amino acids; it undergoes a conformational change upon binding calcium and modulates the function of a number of target proteins (20, 21, 40). While calmodulin was initially considered to be absent in bacteria (3, 6), calmodulin-like proteins (CAMLPs) exhibiting either calcium-binding properties or bovine phosphodiesterase (PDE)-stimulating properties were found in some bacteria (8, 10, 12, 13, 15, 24, 34, 36), but their functions were not explored. Fry et al. (11) purified a CAMLP from Bacillus subtilis but did not demonstrate any role for the protein. We demonstrated the presence of CAMLP in heat-treated extracts of five strains of four species of the genus Mycobacterium (M. smegmatis, M. phlei, M. bovis BCG, and M. tuberculosis H37Ra and H37Rv) by monitoring the stimulation of bovine PDE (4, 5, 8, 26, 30). Ratnakar and Murthy (25) showed that trifluoperazine (TFP), a calmodulin antagonist, inhibits the growth of not only a laboratory strain of the pathogenic tubercle bacillus M. tuberculosis H37Rv, but also two clinical isolates resistant to isoniazid and streptomycin (26; [S. P. Rao, P. S. Murthy, and A. Catanzaro, Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 147(Suppl.):A917, 1993]). We found that TFP also inhibits the growth of Mycobacterium avium [S. P. Rao et al., Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 147(Suppl.):A917, 1993]. These results support the view that mycobacteria contain a protein functionally similar to eukaryotic calmodulin. As part of our studies on a possible regulatory role of CAMLP in the growth and metabolism of mycobacteria, we report here the purification of CAMLP from M. smegmatis, the nucleotide sequence of the gene encoding CAMLP, and the expression and partial characterization of the protein.

Purification of M. smegmatis CAMLP.

The activity of M. smegmatis CAMLP was assayed by the method of Fry et al. (11) based on the stimulation of bovine heart PDE activity by eukaryotic calmodulin. M. smegmatis ATCC 14468 was grown from a stab in Brodie and Gray's medium (1.3% Bacto-Casamino Acids, 0.1% potassium fumarate, 0.2% Tween 80, 0.1% K2HPO4, 0.03% MgSO4, 0.002% FeSO4 [pH 7.0], with KOH) (2) at 37°C in a rotary shaker for 2 to 3 days. With this used as a fresh inoculum, 12 1-liter cultures were grown overnight. The cells were sedimented at 10,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C and washed with 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5). About 70 g (wet weight) of cells was obtained.

All operations were carried out at 4°C except for the high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) purification steps (room temperature). The purification profile of CAMLP at each step was monitored by determination of activity and sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) using a Pharmacia Phast-gel system, and the gels were stained with silver (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

SDS-PAGE analysis of the purification of M. smegmatis CAMLP (MSM-CAMLP). An 8 to 25% gradient gel was run on a Pharmacia PhastSystem and stained with silver. Lanes: 1, supernatant from 100,000 × g centrifugation; 2, supernatant from 65% ammonium sulfate precipitation; 3, Sephadex G-75 pool; 4, HPLC gel filtration pool; 5, HPLC reversed-phase column fraction. The protein molecular mass markers used were carbonic anhydrase (30 kDa), soybean trypsin inhibitor (20.1 kDa), and lysozyme (14.3 kDa).

Seventy grams (wet weight) of cells was suspended (400 mg/ml) in 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.5) containing 1 mM each dithiothreitol, phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and CaCl2 (buffer A). The cells were disrupted by passing them twice through a French pressure cell at 10,000 lb/in2. The crude homogenate was centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 30 min. The cytosol was brought to 65% saturation with ammonium sulfate, and the precipitate was discarded. The supernatant solution (200 ml), enriched for CAMLP, was dialyzed against several changes of 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.5) containing 1 mM CaCl2. After concentration (YM3 Amicon membrane), the protein was fractionated on a Sephadex G-75 (superfine) column (2.5 by 100 cm) with buffer A. The active fractions were pooled, concentrated (YM3 Amicon membrane), and further purified by HPLC gel filtration chromatography (TSK column) with buffer A. CAMLP was eluted as a single sharp peak from this column. The active peak fractions were pooled and subjected to a final purification step by HPLC reversed-phase chromatography with an acetonitrile gradient (0 to 70%) in 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA). Fractions (0.2 ml) were immediately lyophilized to remove solvents. One hundred microliters of buffer A was added to each tube, and the activity was determined. A single fraction from the reversed-phase column contained most of the CAMLP activity. This 579-fold purification resulted in CAMLP with a specific activity of 7,120 U, where 1 U is the amount of M. smegmatis CAMLP required for the conversion of 1 μmol of cyclic AMP (cAMP) to 5′-AMP.

N-terminal amino acid sequence of M. smegmatis CAMLP.

The purest fraction from the reversed-phase HPLC step, judged by silver staining and containing CAMLP activity, was subjected to N-terminal amino acid sequence analysis. A sample of ca. 100 pmol of M. smegmatis CAMLP in 22 μl of 5 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5)-1 mM CaCl2 was applied to a Prospin device (Applied Biosystems). The resulting polyvinylidene difluoride blot was washed twice with 20% MeOH prior to sequencing in an Applied Biosystems Blot cartridge on a model 477A pulsed-liquid protein sequencer equipped with a model 120A PTH analyzer (Applied Biosystems) using methods and cycles supplied by the manufacturer. Data were collected and analyzed on a model 610A data analysis system (Applied Biosystems). The resultant N-terminal sequence was AAMKPRTGDGPLEATK. The presumptive initiator methionine appeared to be absent.

Enzymatic digestion and internal amino acid sequence.

A sample (ca. 200 pmol) of M. smegmatis CAMLP in 5 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5)-1 mM CaCl2 was dried in a Speed-Vac (Savant, Farmingdale, N.J.). The resulting residue was taken up in 25 μl of 8 M urea-0.4 M NH4HCO3 and subjected to reduction, alkylation, and proteolytic digestion with 0.3 μg of modified sequencing-grade trypsin (35). The resulting digest was separated by reversed-phase HPLC on a narrow-bore (2.1 by 250 mm) Vydac 218TP52 column and guard column (Separations Group, Hesperia, Calif.) and eluted at 0.25 ml/min at 35°C utilizing a gradient (9) on a System Gold HPLC equipped with a model 507 autosampler, model 126 programmable solvent module, and model 168 diode array detector (Beckman, Fullerton, Calif.). Solvent A was 0.1% TFA in water, and solvent B was 0.1% TFA in acetonitrile. The column effluent was monitored at 215 and 280 nm. Fractions (125 μl) containing tryptic peptides were applied in 30-μl aliquots to a Biobrene (Applied Biosystems)-treated glass fiber filter and dried prior to amino acid sequencing on the previously described sequencer. Some of the sequences found were VPLEGGGR, TGDGPLEATK, GIVMR, TGDGPLEATKEG, and LVVELTPDEAAALGDELKGV. The second and fourth peptides are in the amino-terminal region (described above).

Cloning of the gene for M. smegmatis CAMLP.

From the amino-terminal amino acid sequence and the sequence of the internal tryptic peptides, three degenerate primers were synthesized for PCR amplification of the M. smegmatis CAMLP gene. Oligonucleotides were synthesized by the phosphoramidite method on an Applied Biosystems 380B DNA synthesizer and purified by HPLC. Primer 1 was designed for the first eight amino acids of the amino-terminal peptide (AAMKPRTGDGPLEATK). Primer 2 was designed for all eight amino acids of an internal peptide (VPLEGGGR), and primer 3 was designed for the last eight amino acids of another internal peptide (LVVELTPDEAAALGDELKGV). The sequences upon which the primers were based are underlined. The primer sequences are as follows: primer 1, 5′-GC(CTGA)GC(CTGA)ATGAA(GA)CC(CTGA)CG(CTGA)AC(CTGA)GG-3′; primer 2, 5′-(CTGA)CG(CTGA)CC(CTGA)CC(CTGA)CC(CT)TC(AGTC)A(GA)(AGTC)GG(CTGA)AC-3′; and primer3, 5′-(CTGA)AC(CTGA)CC(CT)TT(AGTC)A(GA)(CT)TC(GA)TC(CTGA)CC(AGTC)A-3′.

The primer combinations used for the amplification of parts of the CAMLP gene were primers 1 and 2 and 1 and 3. Because of the degenerate nature of the oligonucleotides, high concentrations of the primers and genomic DNA were necessary in the PCR to obtain amplified products. Amplification mixtures in a 100-μl volume contained 100 mM Tris-HCl, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 200 μM deoxynucleoside triphosphate (dNTP), 1 μg of each primer, 1 μg of M. smegmatis genomic DNA, and 2.5 U of Taq polymerase. A 30-cycle amplification was carried out at a melting temperature of 92°C for 1 min, an annealing temperature of 50°C for 1 min, and a polymerization temperature of 72°C for 30 s. PCR products were electrophoresed on 5% polyacrylamide gels. Numerous fragments of identical sizes ranging from 200 to 2,000 bp were amplified under both primer combinations. In addition, a product of about 100 bp appeared with primers 1 and 2 but not with primers 1 and 3. This 100-bp product was selected for DNA sequencing. The band was excised from the gel, and DNA was isolated as described previously (31). The ends of the 100-bp fragment were blunt ended with T4 DNA polymerase, and the fragment was cloned into the SmaI site of M13mp18 (31).

Escherichia coli strainTG-1 transfected with M13mp18 recombinants was grown as described previously (28), and single-stranded DNA was isolated. Several clones were sequenced, and the clone specifying the deduced amino acid sequence identical to the amino-terminal 16 amino acids of the protein was selected to design an oligonucleotide probe for Southern hybridization. The sequence of the probe is 5′-GATGGTCCAATGGAGGTTACAAAAAAAGGA-3′. Forty picomoles of the oligonucleotide probe was labeled with [γ-32P]ATP and T4 polynucleotide kinase (31). The probe was purified with a Qiagen nucleotide removal kit.

Twenty micrograms of genomic DNA was digested with BamHI and SalI. Ten micrograms of digested DNA was electrophoresed through 1% agarose in TAE buffer (40 mM Tris-acetate, 1 mM EDTA [pH 8.0]) and transferred to Nytran membranes (Schleicher & Schuell). The remaining DNA was similarly electrophoresed and used to isolate DNA fragments corresponding to the base pair range of interest deduced from the Southern analysis.

SalI fragments of genomic DNA in the range of 1.4 kbp corresponding to the positive band in Southern analysis were excised from the gel and cloned into the SalI site of pUC19. The recombinant plasmids were introduced into E. coli C600 (λ cI+) cells by electroporation. A total of about 70,000 colonies were obtained on seven Luria-Bertani (22) agar plates (15 by 150 mm) containing ampicillin (100 μg/ml). Colonies were lifted onto nylon membranes (NEF-978A; New England Nuclear), and the cells were lysed according to the manufacturer's recommendations. The colonies were screened with the labeled probe described above. Due to the high density of colonies, positive colonies could not be picked as pure colonies. Instead, colony purification of each positive clone, accompanied by a second round of screening, was performed on plates containing about 200 colonies.

DNA sequence analysis of M. smegmatis CAMLP gene.

The DNA sequence of the 1.4-kbp fragment was determined by the method of Sanger et al. (32) as adapted by Applied Biosystems, Inc., for fluorescent DNA sequencing. Sequence analysis of the cloned gene for M. smegmatis CAMLP revealed that the protein is encoded by 55 codons corresponding to an approximately 6-kDa protein (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

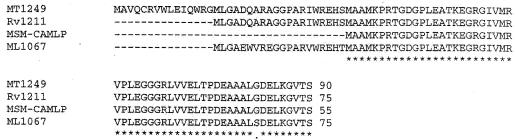

Comparison of the amino acid sequences of CAMLPs from M. smegmatis, M. tuberculosis, and M. leprae. The amino acid sequence of M. smegmatis CAMLP (MSM-CAMLP) deduced from the DNA sequence is shown. The amino acid sequences of M. tuberculosis (MT1249 and Rv1211) and M. leprae (ML1067) CAMLPs, which contain from 20 to 35 extra amino acids as translated from the genomic sequence, are also presented. Identical amino acids are marked with an asterisk.

The molecular mass of calmodulin from eukaryotes is typically about 17 kDa. A 14-kDa protein with calcium-binding property and PDE-stimulating activity was isolated from M. phlei (33). However, the amino acid sequence of this protein was not reported, and hence its homology with calmodulin cannot be determined. The calmodulin gene cloned from another gram-positive bacterial species, Streptomyces erythraeus, has been shown to code for a 17-kDa protein (36), and the CAMLP purified from B. subtilis was shown to have a molecular mass of 23 to 25 kDa (11). Evidence that a protein either identical or similar to M. smegmatis CAMLP exists in other mycobacterial species comes from the M. tuberculosis (www.sanger.ac.uk/Projects/M_tuberculosis and www.tigr.org) and Mycobacterium leprae (www.sanger.ac.uk/Projects/M_leprae) genome sequencing projects (Fig. 2). The homologues in M. tuberculosis H37Rv (Rv1211) and M. leprae (ML1067) were predicted to be 75-amino-acid hypothetical proteins. The homologue in M. tuberculosis CDC1551 (MT1249) is predicted to be a 90-amino-acid protein. The major difference between the M. smegmatis CAMLP, M. tuberculosis Rv1211/MT1249, and M. leprae ML1067 proteins is that the homologous protein in the latter species is suggested to contain 20 or 35 extra amino-terminal amino acids. We suggest that these extra amino acids are derived from an ATG triplet and the subsequent downstream codons, which happen to be in the same reading frame as the real initiator ATG. These extra amino acids do not have the characteristics of a signal sequence. We further emphasize that these extra amino acids are not part of M. smegmatis CAMLP, because the amino-terminal amino acid sequence of M. smegmatis CAMLP, as determined by Edman degradation, matches the deduced amino acid sequences of M. leprae and of M. tuberculosis starting from the 21st amino acid (methionine) (36th amino acid in MT1249) downstream of the previously proposed initiator methionine. The common sequence of 55 amino acids between M. tuberculosis and M. smegmatis is identical. However, there is only one amino acid difference (from glycine to serine) between the M. smegmatis and M. leprae CAMLPs, at position 47. From the amino acid sequence analysis of M. smegmatis CAMLP, we infer that the initiator methionine is processed off the protein.

Expression and purification of M. smegmatis CAMLP as a fusion protein with GroEL and cleavage with enterokinase.

The CAMLP was purified as a fusion protein with the GroEL apical domain by cloning the gene into a modified pRE1 expression vector (29). The modified vector encodes the E. coli GroEL apical domain (41) followed by a glycine- and serine-rich peptide linker and the enterokinase recognition sequence. (Details of the vector construction will be reported elsewhere.) A DNA cartridge with multiple cloning sites (NdeI-SstI-KpnI-SmaI-BamHI-XbaI-EcoRV-SalI) was introduced after the coding sequence for enterokinase. The M. smegmatis CAMLP gene was cloned into the NdeI and BamHI sites. A recombinant was isolated in E. coli C600 (λ cI+). A general procedure for expression in E. coli strain MZ1(cIts857) (42) has been described previously (29).

For purification of the fusion protein, 5 g of MZ1-induced cells harboring the GroEL apical domain-CAMLP fusion protein was suspended in 50 ml of 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) containing 1 mM CaCl2, 1 mM dithiothreitol, and 0.1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride. The French press extract was brought to 70°C and maintained at this temperature for 2 min with mild stirring. The extract was immediately cooled in ice. Precipitated proteins were removed by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 15 min. The fusion protein was purified from the supernatant by absorption onto a DEAE-cellulose column (1.5 by 20 cm) and elution with a 0 to 0.4 M NaCl gradient. The fusion protein was eluted as a sharp peak, as judged by SDS-PAGE. Further purification on Sephadex G-75 (superfine) column (2.5 by 100 cm), equilibrated and eluted with 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 50 mM NaCl, and 1 mM CaCl2, yielded nearly homogeneous protein with a final yield of 10 mg (19) of fusion protein. The fusion protein was digested with enterokinase, and CAMLP was separated from GroEL by gel filtration chromatography using a BIOSEP-SEC-S3000 HPLC column (21.2 by 600 mm) (Fig. 3) from Phenomenex.

FIG. 3.

SDS-PAGE analysis of the purification of M. smegmatis CAMLP from E. coli. The GroEL apical domain-CAMLP fusion protein was purified, digested with enterokinase, and further purified from the tag as described in the text. A sample of 1.5 μg of each protein was electrophoressed through an 8 to 25% gradient gel on a Pharmacia PhastSystem and stained with Coomassie R-250. Lanes: left, molecular mass markers (from top to bottom) for 94, 67, 43, 30, 20.1, and 14.4 kDa; middle, GroEL apical domain-CAMLP fusion protein; right, CAMLP after digestion with enterokinase.

The Ca2+-binding site.

Eukaryotic calmodulin contains four calcium-binding domains referred to as “EF hands” (16). Analysis of M. smegmatis CAMLP for calcium-binding domains revealed one putative Ca2+ site (Fig. 4). Given the size of M. smegmatis CAMLP (one-third that of eukaryotic calmodulin), it is not surprising that only one Ca2+-binding domain is found in the protein. There are several examples of “ancestral” calcium-binding sites with little or no homology to a typical EF hand, even among eukaryotic calmodulins (14, 38). The homology of the putative calcium-binding site in M. smegmatis CAMLP is also atypical with respect to the EF hand signature. The best alignment of the putative calcium-binding site in M. smegmatis CAMLP to an EF hand motif results in a 4-amino-acid spacer (alanine as an extra amino acid) between the conserved GDG and TKE sequences compared to 3 amino acids in the eukaryotic EF hand motifs. The calcium-binding site in M. smegmatis CAMLP contains an aspartate residue and two glutamate residues, satisfying the requirement for calcium binding. Fry et al. (11) purified a 24-kDa CAMLP from B. subtilis. Their attempts to clone the gene for this protein by using primers for EF motifs of eukaryotic calmodulin did not succeed. This suggests that, in at least one type of bacteria other than M. smegmatis, the sequence is different in the EF motif from that of eukaryotic calmodulin (18, 37, 39).

FIG. 4.

Alignment of the calcium-binding sites in M. smegmatis CAMLP (MSM-CAMLP) and eukaryotic calmodulin. Four calcium-binding sites of eukaryotic calmodulin are presented as EF hands 1 to 4. The single putative calcium-binding site of MSM-CAMLP is shown aligned with the eukaryotic calcium-binding sites.

Additional evidence for the presence of a calcium-binding site in M. smegmatis CAMLP comes from the calcium dependence for the activity of the EGTA-treated protein, as measured by the activation of bovine PDE. As shown in Table 1, M. smegmatis CAMLP dialyzed against EGTA lost the ability to activate PDE. However, by adding Ca2+ to EGTA-treated CAMLP, partial restoration of the activity was observed. This finding demonstrates a role for calcium in the activation of PDE by CAMLP.

TABLE 1.

Activation of bovine PDE by M. smegmatis CAMLP and the requirement for calciuma

| Addition | % of basal activity |

|---|---|

| None (basal PDE) | 100 |

| Bovine calmodulin (1.7 μg) | 479 |

| Untreated CAMLP | 339 |

| EGTA-treated CAMLP | |

| Without CaCl2 | 97 |

| With 50 μM CaCl2 | 114 |

| With 100 μM CaCl2 | 155 |

Purified M. smegmatis CAMLP (395 ng of protein) was incubated with EGTA (10 mM) at 4°C for 30 min and then dialyzed against several changes of deionized water. The M. smegmatis CAMLP was assayed for its ability to stimulate the activator-deficient PDE activity. The activity of basal PDE was taken as 100%. The results are the average of three experiments.

A clone was engineered that expressed M. smegmatis CAMLP in which the C-terminal serine was replaced by tryptophan to facilitate measurements of the A280. Sedimentation equilibrium studies (7) of this expressed protein showed it to be monomeric in the absence or presence of 1 mM CaCl2 (data not shown). Mass spectral analysis of M. smegmatis CAMLP in the absence and presence of Ca2+ showed no conclusive evidence of binding of Ca2+ to the protein under the conditions in which we observed strong binding of Ca2+ to bovine brain calmodulin (data not shown). The inability to demonstrate any binding of calcium to the purified protein suggests that the calcium binding to M. smegmatis CAMLP requires its association with either PDE or some accessory proteins.

Reaction of M. smegmatis CAMLP with anticalmodulin antibodies.

The purified M. smegmatis CAMLP was shown to react with anticalmodulin antibodies (data not shown). Wells of a microtiter plate were coated with 100 μl of antigen (200 U of either bovine calmodulin in 0.1% bovine serum albumin [BSA] or M. smegmatis CAMLP) for 2 h at 37°C. After decanting the solution, the wells were washed twice with Tris-buffered saline (TBS; 10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 0.1 M NaCl, 0.05% Tween 20). Nonspecific binding was blocked with 100 μl of TBS containing 1% BSA at 37°C for 1 h. After washing the wells twice as described above, 100 μl of primary antibody (freshly made 1:100 dilution of anticalmodulin antibody in blocking buffer) was added, and the plates were incubated for 2 h at 37°C and then overnight at 4°C. The wells were washed twice and treated with 100 μl of protein A-peroxidase conjugate (1:500 dilution of 0.1 mg in 500 μl of 10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5]) for 1 h at room temperature. A 100-μl aliquot of 0.1 M o-phenylenediamine in 0.1 M citrate-phosphate buffer (pH 5.0) and 1 μl of 30% H2O2 were added to each well, and the plates were kept in the dark for 30 min at room temperature. This was followed by the addition of 100 μl of 6 N HCl. Both the control calmodulin and M. smegmatis CAMLP showed a positive response.

Inhibition of M. smegmatis CAMLP activity by TFP.

Pathogenic species of mycobacteria cause devastating human diseases, including tuberculosis and leprosy. The emergence of drug-resistant tubercle bacilli is a major threat to public health (1). The challenge in treating patients infected with drug-resistant tubercle bacilli is to discover potential new antimicrobial drugs. During the course of our work on the mycobacterial CAMLP, we found that TFP, a calmodulin antagonist, inhibited the growth of M. avium [S. P. Rao et al., Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 147(Suppl.):A917, 1993] and M. tuberculosis H37Rv, which are susceptible and resistant, respectively, to isoniazid (25, 27; [S. P. Rao et al., Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 147(Suppl.):A917, 1993]). Since TFP is a calmodulin antagonist, we tested the effect of TFP on the ability of M. smegmatis CAMLP to activate PDE. Table 2 shows that TFP strongly inhibited the activity of M. smegmatis CAMLP, providing further evidence that M. smegmatis CAMLP has properties akin to eukaryotic calmodulin.

TABLE 2.

Activation of bovine PDE by M. smegmatis CAMLP purified from E. coli and the effect of TFPa

| Protein | % of basal activity |

|---|---|

| None (basal PDE) | 100 |

| Bovine calmodulin (1.7 μg) | 530 |

| CAMLP | 262 |

| +0.25 μg of TFP | 191 |

| +0.50 μg of TFP | 131 |

| +1.00 μg of TFP | 109 |

| +5.00 μg of TFP | 101 |

M. smegmatis CAMLP (0.5 μg of protein) was assayed for its ability to stimulate the activator-deficient PDE activity. The activity of basal PDE was taken as 100%. The results are the average of two experiments.

General features of prokaryotic CAMLPs.

Recently, Nagai et al. (23) studied CAMLPs from Bordetella pertussis, Bordetella parapertussis, and Bordetella bronchisptica. The Bordetella CAMLP purified to homogeneity had a molecular mass of 10 kDa. These findings together with those from our earlier studies (P. Reddy, R. Prasad, and P. S. Murthy, Sixteenth Int. Congress Biochem. Mol. Biol., p. 69, 1994) suggest that some bacteria have CAMLPs of smaller size (6 to 10 kDa). Our work is the first report on the cloning and sequencing of a lower-molecular-mass CAMLP gene from bacteria. We suggest that differences in the molecular masses of bacterial CAMLPs and eukaryotic calmodulins may be evolutionary. The present study shows that the CAMLP from M. smegmatis is similar to eukaryotic calmodulin in its ability to stimulate bovine PDE, dependence on calcium, sensitivity to TFP, and reaction with bovine anticalmodulin antibody, as judged by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, although its molecular size is one-third of that of the eukaryotic calmodulin. These properties of the protein, typical of eukaryotic calmodulin, qualify the protein to be termed a CAMLP (40).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence of the gene encoding CAMLP has been submitted to the GenBank database under accession no. AY319523 (Protein_id, AAP88233).

Acknowledgments

We thank Peng-Peng Zhu, Laboratory of Biochemical Genetics, NHLBI, NIH, for help with the DNADRAW program. Fuquan Yang and Henry Fales, Laboratory of Biophysical Chemistry, NHLBI, NIH, kindly carried out the mass spectrometric analysis of CAMLP.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bloom, B. R., and C. J. Murray. 1992. Tuberculosis: commentary on a reemergent killer. Science 257:1055-1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brodie, A. F., and C. T. Gray. 1956. Phosphorylation coupled to oxidation in bacterial extracts. J. Biol. Chem. 219:853-862. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burgess, W. H., D. K. Jemiolo, and R. H. Kretsinger. 1980. Interaction of calcium and calmodulin in the presence of sodium dodecyl sulfate. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 623:257-270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burra, S. S., P. H. Reddy, S. M. Falah, T. A. Venkitasubramanian, and P. S. Murthy. 1991. Calmodulin-like protein and the phospholipids of Mycobacterium smegmatis. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 64:189-194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burra, S. S., P. H. Reddy, and P. S. Murthy. 1995. Effect of some antitubercular drugs on the calmodulin content of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Indian J. Clin. Biochem. 10:126-128. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clarke, M., W. L. Bazari, and S. C. Kayman. 1980. Isolation and properties of calmodulin from Dictyostelium discoideum. J. Bacteriol. 141:397-400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dimitrova, M. N., R. H. Szczepanowski, S. B. Ruvinov, A. Peterkofsky, and A. Ginsburg. 2002. Interdomain interaction and substrate coupling effects on dimerization and conformational stability of enzyme I of the Escherichia coli phosphoenolpyruvate:sugar phosphotransferase system. Biochemistry 41:906-913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Falah, A. M. S., R. Bhatnagar, N. Bhatnagar, Y. Singh, G. S. Sidhu, P. S. Murthy, and T. A. Venkitasubramanian. 1988. On the presence of calmodulin like protein in mycobacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 56:89-93. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fernandez, J., M. DeMott, D. Atherton, and S. M. Mische. 1992. Internal protein sequence analysis: enzymatic digestion for less than 10 micrograms of protein bound to polyvinylidene difluoride or nitrocellulose membranes. Anal. Biochem. 201:255-264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fry, I. J., L. Villa, G. D. Kuehn, and J. H. Hageman. 1986. Calmodulin-like protein from Bacillus subtilis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 134:212-217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fry, I. J., M. Becker-Hapak, and J. H. Hageman. 1991. Purification and properties of an intracellular calmodulinlike protein from Bacillus subtilis cells. J. Bacteriol. 173:2506-2513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harmon, A. C., D. Prasher, and M. J. Cormier. 1985. High-affinity calcium-binding proteins in Escherichia coli. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 127:31-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iwasa, Y., K. Yonemitsu, K. Matsui, K. Fukunaga, and E. Miyamoto. 1981. Calmodulin-like activity in the soluble fraction of Escherichia coli. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 98:656-660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kawamura, S., K. Takamatsu, and K. Kitamura. 1992. Purification and characterization of S-modulin, a calcium-dependent regulator of cGMP phosphodiesterase in frog rod photoreceptors. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 186:411-417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kerson, G. W., J. A. Miernyk, and K. Budd. 1984. Evidence for the occurrence of and possible physiological role for cyanobacterial calmodulin. Plant Physiol. 75:222-227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klee, C. B., T. H. Crouch, and P. G. Richman. 1980. Calmodulin. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 69:489-515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klee, C. B., and T. C. Vanaman. 1982. Calmodulin. Adv. Protein Chem. 35:213-321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leppla, S. H. 1982. Anthrax toxin edema factor: a bacterial adenylate cyclase that increases cyclic AMP concentrations of eukaryotic cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 79:3162-3166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lowry, O. H., N. J. Rosebrough, A. L. Farr, and R. J. Randall. 1951. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J. Biol. Chem. 193:265-275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Manalan, A. S., and C. B. Klee. 1984. Calmodulin. Adv. Cyclic Nucleotide Protein Phosphorylation 18:227-278. [PubMed]

- 21.Means, A. R., M. F. VanBerkum, I. Bagchi, K. P. Lu, and C. D. Rasmussen. 1991. Regulatory functions of calmodulin. Pharmacol. Ther. 50:255-270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller, J. H. 1972. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 23.Nagai, M., M. Endoh, H. Danbara, and Y. Nakase. 1994. Purification and characterization of Bordetella calmodulin-like protein. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 116:169-174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pettersson, A., and B. Bergman. 1989. Calmodulin in heterocystous cyanobacteria: biochemical and immunological evidence. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 51:95-99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ratnakar, P., and P. S. Murthy. 1992. Antitubercular activity of trifluoperazine, a calmodulin antagonist. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 76:73-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ratnakar, P., and P. S. Murthy. 1993. Trifluoperazine inhibits the incorporation of labelled precursors into lipids, proteins, and DNA of Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 110:291-294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ratnakar, P., and P. S. Murthy. 1994. Preliminary studies on the inhibition of surface growth of isoniazid and streptomycin resistant strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv by trifluoperazine. Indian J. Tuberc. 41:35-37. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reddy, P., and K. McKenney. 1996. Improved method for the production of M13 phage and single-stranded DNA for DNA sequencing. BioTechniques 20:854-859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reddy, P., A. Peterkofsky, and K. McKenney. 1989. Hyperexpression and purification of Escherichia coli adenylate cyclase using a vector designed for expression of lethal gene products. Nucleic Acids Res. 17:10473-10488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reddy, P. H., S. S. Burra, and P. S. Murthy. 1992. Correlation between calmodulin like protein, phospholipids, and growth in glucose-grown Mycobacterium phlei. Can. J. Microbiol. 38:339-342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 32.Sanger, F., S. Nicklen, and A. R. Coulson. 1977. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 74:5463-5467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sarma, P. V. G. K., P. U. Sarma, and P. S. Murthy. 1998. Isolation, purification and characterization of intracellular calmodulin like protein (CALP) from Mycobacterium phlei. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 159:27-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shyu, Y. T., and P. M. Foegeding. 1991. Purification and some characteristics of a calcium-binding protein from Bacillus cereus spores. J. Gen. Microbiol. 137:1619-1623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stone, K. L., and K. R. Williams. 1993. Enzymatic digestion of proteins and HPLC peptide isolation, p. 43-101. In P. Matsudaira (ed.), A practical guide to protein and peptide purification for microsequencing, 2nd ed. Academic Press, San Diego, Calif.

- 36.Swan, D. G., R. S. Hale, N. Dhillon, and P. F. Leadlay. 1987. A bacterial calcium-binding protein homologous to calmodulin. Nature 329:84-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Swan, D. G., J. Cortes, R. S. Hale, and P. F. Leadlay. 1989. Cloning, characterization, and heterologous expression of the Saccharopolyspora erythraea (Streptomyces erythraeus) gene encoding an EF-hand calcium-binding protein. J. Bacteriol. 171:5614-5619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Takamatsu, K., K. Kitamura, and T. Noguchi. 1992. Isolation and characterization of recoverin-like Ca2+-binding protein from rat brain. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 183:245-251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Watterson, D. M., F. Sharief, and T. C. Vanaman. 1980. The complete amino acid sequence of the Ca2+-dependent modulator protein (calmodulin) of bovine brain. J. Biol. Chem. 255:962-975. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wolff, J., G. H. Cook, A. R. Goldhammer, and S. A. Berkowitz. 1980. Calmodulin activates prokaryotic adenylate cyclase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 77:3841-3844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zahn, R., A. M. Buckle, S. Perrett, C. M. Johnson, F. J. Corrales, R. Golbik, and A. R. Fersht. 1996. Chaperone activity and structure of monomeric polypeptide binding domains of GroEL. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:15024-15029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zuber, M., T. A. Patterson, and D. L. Court. 1987. Analysis of nutR, a site required for transcription antitermination in phage lambda. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 84:4514-4518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]