Abstract

Obesity is characterized by alterations in immune and inflammatory function. In order to evaluate the potential role of cytokine expression by peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) in obesity-associated inflammation, we studied serum protein levels and mRNA levels in PBMC of interleukin (IL)-6, IL-1β, tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α and IL-1Ra in nine lean and 10 obese subjects. Serum IL-1β was undetectable, IL-1Ra serum levels were elevated, serum levels of TNF-α were decreased and serum levels of IL-6 were similar in obese subjects compared to lean subjects, while transcript levels of IL-6, IL-1β and TNF-α, but not IL-1Ra, were decreased in PBMC from obese subjects. PBMC from obese subjects did, however, up-regulate cytokine expression in response to leptin. Thus, obesity-associated changes in IL-1Ra serum levels and IL-6 mRNA levels were not correlated with changes in cognate mRNA and serum levels, respectively, while TNF-α serum levels and PBMC mRNA levels were both decreased in obese patients. While immune alterations in obesity are manifest in peripheral blood lymphocytes, the general lack of correlation between altered serum levels and altered PBMC gene expression suggests that PBMC may not be the source of aberrant serum cytokine levels in obesity.

Keywords: cytokine, interleukin-1 receptor antagonist, interleukin-1β, interleukin-6, lymphocyte, obesity, tumour necrosis factor-α

Introduction

Obesity is a global health crisis of epidemic proportions that exacts an enormous toll on public health. Obesity has detrimental effects on virtually all physiological systems. As its underlying molecular mechanisms are elucidated, it has become clear that obesity has profound effects on immunity and inflammation. Obesity is associated with an inflammatory state that has been implicated in the pathogenesis of many obesity-related comorbidities. Clinical observations support this concept; numerous studies confirm an increased risk of virtually all types of cancer in obese patients [1], suggesting a defect in immune surveillance. Data from animal models demonstrate a lower incidence of cancer associated with caloric restriction, further supporting a link between weight regulation and carcinogenesis [2]. Other data demonstrate alterations in inflammation in obesity, with elevation of serum inflammatory markers in obese subjects, including interleukin (IL)-6, tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α, soluble TNF-αR, C-reactive protein and complement [3–8]. Inflammatory mediators are similarly elevated in patients suffering from many comorbidities of obesity independent of body weight, including atherosclerosis, diabetes and steatohepatitis [3,9–14]. A state of chronic systemic inflammation may therefore underlie the pathogenesis of many obesity-related comorbidities.

Bariatric surgery is the only effective current treatment for obesity. Given current resource limitations, however, it is estimated that less than 1% of clinically eligible morbidly obese patients in the United States have access to surgical therapy [15]. Pharmacological therapies for obesity-related comorbidities independent of weight loss would be applied more easily to millions of obese patients who do not have access to surgery, and probably result in significant improvements in patient health and associated costs of care. Therapies directed at underlying immune and inflammatory defects in obesity are an excellent target for research as these processes are associated with many obesity-related comorbidities, including diabetes, atherosclerosis, liver disease and cancer.

Leptin is a compelling candidate for a mediator of obesity's effects on immunity and inflammation. Leptin is a16-kDa protein secreted primarily by adipocytes that binds receptors in the hypothalamic appetite centre to effect satiety. Obese (ob) mice, which carry an inactivating mutation in the leptin gene, manifest severe obesity, as well as multiple defects in endocrine, reproductive and immune function [16]. Rare human families with leptin mutations are obese, with immune derangements as well [17]. The vast majority of obese humans do not have leptin mutations, however, but display central leptin resistance, with markedly elevated serum leptin levels [18]. Leptin therefore plays an important role in human obesity. Recent studies demonstrate that leptin is also an important regulator of immune function. Leptin is a member of the long-chain helical cytokine family, and leptin receptors are expressed on virtually all lymphocytes [19–21]. Leptin has been implicated in the regulation of lymphocyte and monocyte function, and specifically has profound effects on lymphocyte and monocyte cytokine expression.

Much prior interest in cellular mediators of inflammation in obesity has focused on intrahepatic and adipose tissue immune cell function [22,23]. Access to these tissue depots is limited, however. We therefore elected to study peripheral blood lymphocytes, and hypothesize that alterations in immune function associated with obesity are manifested in the peripheral immune system. Cytokines are critical effectors of lymphocyte function, and their metabolism is aberrant in obesity. We therefore elected to focus initial study on this aspect of peripheral lymphocyte function and studied four inflammatory cytokines whose regulation is altered in obesity. Given relatively easy access to peripheral blood cells compared to hepatic or adipose-associated immune cells, study of peripheral immune cells would expedite research into mechanisms of immune dysfunction in obesity. Such information will direct further research towards the development of therapies to treat the inflammatory state associated with obesity. Such therapy has the potential to treat multiple obesity-related comorbidities independent of weight loss.

Materials and methods

Research subjects

Morbidly obese patients (BMI > 35) presenting to the Oregon Health and Science University (OHSU) bariatric surgery clinic were enrolled and consented with Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval. Lean (BMI < 25) volunteers with no significant medical problems were recruited from the OHSU community as controls. All patients and lean control subjects denied any recent illness. Peripheral blood was drawn from all patients during their preoperative clinic visit, and from lean control subjects. Because of limitations due to the amount of blood required for assays, separate lean and obese subject groups were used for experiments studying serum cytokine levels and cytokine transcript levels in circulating peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) (subject group 1), and for experiments studying cytokine expression in cultured PBMC (subject group 2) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Research subject clinical information.

| Subject group 1: serum cytokine levels, circulating PBMC cytokine transcription | Subject group 2: cultured PBMC cytokine expression | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Obese subjects | Lean subjects | Obese subjects | Lean subjects | |

| n | 9 | 10 | 10 | 9 |

| BMI (mean, median) | 48, 49 | 23, 22 | 50, 46 | 22, 22 |

| Age (mean, median) | 46, 45 | 35, 32 | 45, 44 | 37, 33 |

| Gender (M/F) | 1/8 | 3/7 | 5/5 | 0/9 |

| Co-morbidities | ||||

| Diabetes | 3 | 0 | 5 | 0 |

| Sleep apnoea | 2 | 0 | 4 | 0 |

| Depression | 5 | 0 | 5 | 0 |

| Hypertension | 8 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Osteoarthritis | 3 | 0 | 4 | 0 |

| GERD | 6 | 0 | 4 | 0 |

| Hyperlipidaemia | 5 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Medications | ||||

| Oral hypoglycaemic | 3 | 0 | 4 | 0 |

| Insulin | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Antihypertensive | 8 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| NSAID | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Antidepressant | 3 | 0 | 5 | 0 |

| Statin | 5 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Antacid | 6 | 0 | 4 | 0 |

Sleep apnoea was defined by diagnosis by polysomnography and use of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP). Osteoarthritis was defined by clinical diagnosis and the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug or other pain medication. Depression was defined by clinical diagnosis and the use of antidepressant medication. PBMC: peripheral blood mononuclear cells.

PBMC isolation and culture

PBMC were isolated by Ficoll gradient separation. A total of 100 000 cells were cultured in 1·25 ml of RPMI + 10% human serum ± leptin (100 nM) for 24 h, after which cells were harvested for RNA preparation or supernatants were harvested for enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Vehicle (leptin diluent buffer) was used as a negative control for leptin. Serum was harvested from peripheral blood after centrifugation of red blood cells and lymphocytes.

RNA preparation and quantitative reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (qRT–PCR)

RNA was prepared from fresh or cultured PBMC using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Inc., Carlsbad, CA, USA). RNA was reverse-transcribed using random hexamer primers, and qRT–PCR performed using SYBR Green I reagent and primers specific for IL-1β, IL-1Ra, IL-6 and TNF-α on an ABI 7900 real-time thermocycler (Applied Biosystems, Inc., Foster City, CA, USA). Primers specific for glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) were used as an endogenous control, and cytokine transcript levels were normalized to GAPDH levels. The 2–ddCT relative quantification method was used to calculate fold difference in transcript levels between samples [24]. Efficiencies of amplification of GAPDH and cytokine transcripts were determined to be equivalent over a range of template concentrations. Primers specific for β-actin were used as an alternative endogenous control gene in select experiments to confirm results using GAPDH primers.

ELISA

Peripheral serum and cell culture supernatants were subject to ELISA using standard kits (R&D Systems, Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA) for IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α and IL-1R antagonist (IL-1Ra).

Statistical analysis

Independent t-test was used to determine the significance of differences in age and BMI between subject groups, and between transcript levels from qRT–PCR between lean and obese subject groups, and for serum cytokine levels from ELISA between lean and obese subject groups. The Mann–Whitney U-test was used to determine the significance of differences in cytokine expression as determined by ELISA in cultured PBMC for each culture condition between lean and obese subject groups. Wilcoxon's signed ranks test was used to determine the significance of differences in cytokine expression as determined by ELISA between PBMC cultured with or without leptin within lean and obese subject groups. Linear regression analysis, with age and subject group as independent variables, was used to determine if a correlation existed between age and serum cytokine levels or circulating PBMC transcript levels. A P-value of 0·05 was the threshold for significance.

Results

Research subject demographics

Research subject clinical information is shown in Table 1. For experiments studying serum cytokine levels and cytokine transcript levels in circulating PBMC, mean age was 35 and 46 years old for lean and obese subjects, respectively (P = 0·057), and mean BMI was 23 and 48 for lean and obese subjects, respectively (P < 0·001). For experiments studying cytokine expression in cultured PBMC mean age was 37 and 46 years old for lean and obese subjects, respectively (P = 0·046), and mean BMI was 22 and 50 for lean and obese subjects, respectively (P < 0·001).

Obese subjects demonstrate abnormalities in serum inflammatory cytokine levels

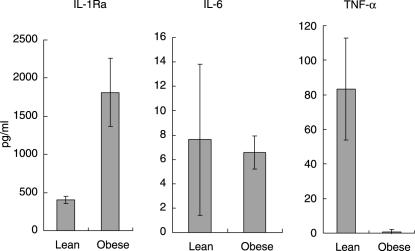

Mean serum IL-1Ra serum levels were 403 and 1812 pg/ml in lean and obese subjects, respectively (P = 0·004). Mean serum IL-6 serum levels were 9·3 and 6·6 pg/ml in lean and obese subjects, respectively (P = 0·674). Mean serum TNF-α serum levels were 84 and 1 pg/ml in lean and obese subjects, respectively (P = 0·016) (Fig. 1). IL-1β was undetectable in the serum of all lean and obese subjects. Linear regression analysis demonstrated no association between cytokine levels and age (P > 0·37 for all cytokines), while the association between subject group and serum cytokine levels remained significant for TNF-α and IL-1Ra (P = 0·026 and P = 0·025, respectively).

Fig. 1.

Serum inflammatory cytokine levels. Mean serum cytokine levels in lean and obese subjects as determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Mean serum interleukin (IL)-1Ra levels were 403 and 1812 pg/ml in lean and obese subjects, respectively (P = 0·004, independent t-test). Mean serum IL-6 serum levels were 7·6 and 6·6 pg/ml in lean and obese subjects, respectively (P = 0·875, independent t-test). Mean serum tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α serum levels were 83 and 0·8 pg/ml in lean and obese subjects, respectively (P = 0·015, independent t-test). IL-1β was undetectable in the serum of both lean and obese subjects. Error bars are standard error of the mean. Note different ordinate scales.

Circulating PBMC from obese subjects demonstrate abnormalities of inflammatory cytokine transcript levels

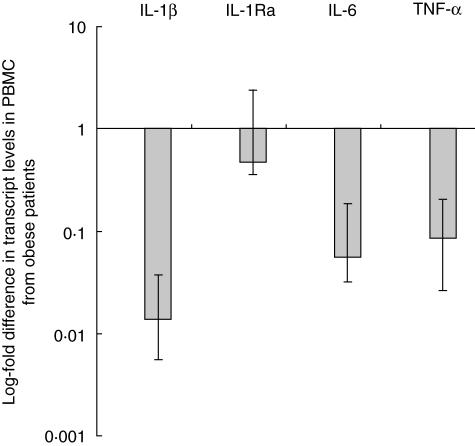

Transcript levels were studied in circulating PBMC from lean and obese patients from which RNA was prepared immediately after peripheral blood draw. Data are shown as the fold difference in transcript levels in PBMC from obese subjects compared to transcript levels in PBMC from lean subjects. Transcript levels of IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α were significantly lower in fresh PBMC from obese subjects compared to lean subjects (0·014, 0·056 and 0·085 times lower, respectively, P < 0·005 in each case). Transcript levels of IL-1Ra were not significantly different between obese and lean subjects (0·4739 times lower, P = 0·57) (Fig. 2). Linear regression analysis demonstrated no association between cytokine transcript levels and age (P > 0·28 for all cytokines), while the association between subject group and cytokine transcript levels remained significant for IL-6, IL-1β and TNF-α (P < 0·003 in each case), but not IL-1Ra (P = 0·53). Primers specific for β-actin were used as an alternative endogenous control gene in select experiments, and demonstrated results similar to those observed using GAPDH primers (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

Cytokine transcript levels in circulating peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) from obese subjects. Mean log fold difference in transcript levels in PBMC from obese subjects compared to transcript level in PBMC from lean subjects as referent = 1, as determined by quantitative reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (qRT–PCR). Log-fold change in transcript level shown numerically under each bar. Differences significant for interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6, tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α (P < 0·005 in each case, single-sample t-test), but not IL-1RA (P = 0·57, single-sample t-test). Error bars are standard error of the mean. The ordinate is log-scale.

PBMC from obese subjects demonstrate decreased expression of inflammatory cytokines in culture, but retain the capacity to up-regulate cytokine expression in response to leptin

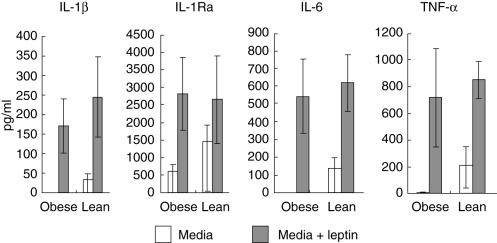

PBMC from obese subjects cultured for 24 h demonstrated markedly lower basal expression of IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α (P < 0·03 in each case), as well as lower levels of IL-1Ra expression which approached significance (P = 0·072). Leptin increased expression of IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α and IL-1Ra in PBMC from obese subjects compared to untreated cells (P < 0·01 in all cases). Leptin also increased expression of IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α in PBMC from lean subjects compared to untreated cells (P < 0·01 in all cases); this difference approached significance only for IL-1Ra in lean subjects (P = 0·086). PBMC from obese subjects therefore retain the capacity to mount a response to pharmacologic doses of leptin (100 nm), increasing expression of IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α and IL-1Ra to the same levels as lean controls (P > 0·3 in all cases). PBMC cultured with vehicle control showed results similar to cells cultured in the absence of leptin (data not shown) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Cytokine concentrations in cultured peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC). Median cytokine concentrations as determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) in supernatants from PBMC from obese and lean subjects cultured with and without leptin. Markedly lower cytokine expression in PBMC from obese subjects compared to PBMC from lean subjects cultured in media only were statistically significant for interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6 and tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α (P < 0·001 in all cases, Mann–Whitney U-test), but approached significance only for IL-1Ra (P = 0·072, Mann–Whitney U-test). Differences in cytokine expression in PBMC cultured with media + leptin between obese and lean subject groups were not significant for all cytokines (P > 0·3 in all cases). Differences in cytokine expression in PBMC cultured with media only compared to PBMC cultured with media + leptin within each group (obese or lean) were statistically significant for IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α in both lean and obese subject groups (P < 0·01 in all cases, Wilcoxon's signed ranks test), and for IL-1Ra in obese subjects (P = 0·005, Wilcoxon's signed ranks test), but only approached significance for IL-1Ra in lean subjects (P = 0·086). Error bars are interquartile ranges. Note different ordinate scales.

Discussion

These data demonstrate marked abnormalities in inflammatory cytokine expression patterns in PBMC from obese subjects, characterized by abnormalities in serum cytokine levels and decreased cytokine transcript levels in fresh and cultured PBMC. Others have demonstrated elevated serum cytokine levels in obese subjects, including IL-1Ra [4,25–27], IL-6 [8,28–30] and TNF-α[8,29–32]. Fewer data study IL-1β levels in obesity, but at least two studies demonstrate elevated serum IL-1β levels in obese children [28,32]. Our data conflict with these previously published data in that serum IL-6 and IL-1β levels were similar between groups and TNF-α levels were lower in obese subjects, although others have shown no elevation of serum IL-6 or TNF-α in obese patients [33,34], similar to our data. There are a number of potential explanations for these discordant data. First, serum levels of cytokines vary widely among individuals [35], suggesting that differences among studies may be in part attributable to overall variation within the human population. Differences in patient comorbidities may also explain differences in serum cytokine levels. For example, others have demonstrated a correlation between severity of sleep apnea, but not BMI, and serum IL-6 and TNF-α levels in obese patients [36]. Serum cytokine levels may be more likely to be elevated in android rather than gynecoid obesity [37,38], and studies differ with respect to the proportion of patients with android fat distribution. Age may also be a factor in serum levels of specific cytokines [34], suggesting yet another clinical factor that might explain variability in results. Finally, patients often lose weight in anticipation of surgery, and weight loss has been shown to reduce elevated serum cytokine levels [5,8]. Subjects in this study underwent phlebotomy within a month of surgery, during which time many of them were actively losing weight, which might reverse pre-existing abnormalities in serum cytokine levels. Larger studies in which patients are better matched for the potential clinical variables that might impact on serum cytokine levels will define precise alterations in serum cytokine levels in different subsets of obese patients.

Cytokine transcript levels in circulating PBMC from obese subjects did not reflect serum cytokine levels but, rather, were markedly decreased for IL-6, TNF-α and IL-1β, but not IL-1Ra. This may be the result of post-transcriptional regulation of cytokine expression, leading to a lack of correlation between transcript levels measured by qRT–PCR and protein levels measured by ELISA. Alternatively, however, this discordance between serum cytokine levels and cytokine transcript levels in PBMC suggests that peripheral blood lymphocytes are not the primary source of elevated serum inflammatory cytokines in obesity. Elevated cytokines may be derived from cytokine-producing cells other than peripheral blood lymphocytes, such as intrahepatic or adipose tissue-associated cells, that undergo different alterations in cytokine expression in response to obesity. Others have, for example, shown up-regulation of IL-1Ra and TNF-α expression in macrophages isolated from subcutaneous adipose tissue [22], in contrast to our data studying PBMC. Adipose tissue has also been suggested as a potential source of elevated TNF-α serum levels in obesity [23]. The observed decrease in cytokine transcript levels in PBMC may be a compensatory response to elevated expression at other in vivo sites. Further study of both peripheral blood and tissue-specific lymphocytes will define functional differences among immune cell subsets.

Transcript levels of IL-1Ra in circulating and cultured PBMC were not significantly different between subject groups, in contrast to the other cytokines studied. IL-1Ra is considered to have an anti-inflammatory function [39], in contrast to IL-1β, TNF-α and IL-6, and it is of interest that it appears to be regulated differently in PBMC in obesity. Selective aberrations in expression among different cytokines in obesity might disrupt the balance of inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines, thus predisposing to an inflammatory state.

Prior data demonstrate an important role for leptin in the regulation of lymphocyte cytokine expression. We used an in vitro culture system to explore the role of leptin in regulating cytokine expression in PBMC. Cultured PBMC from obese subjects had significantly lower expression of IL-6, TNF-α and IL-1β, which only approached significance for IL-1Ra, confirming a pattern of altered expression similar to that seen in circulating PBMC above. Leptin treatment increased expression of all four cytokines in both lean and obese subjects, although this increase only approached significance for IL-1Ra in lean subjects. Others have shown that leptin up-regulates expression of TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-1Ra in both monocytes and T cells [40–42], and our data extend these results to unfractionated PBMC. While leptin has been shown to increase IL-1β expression in the hypothalamus [43], our data are the first of which we are aware that demonstrates that leptin up-regulates IL-1β expression in lymphocytes.

Human obesity is characterized by hypothalamic resistance to the effects of leptin on satiety [44,45]. Our data suggest that no such resistance exists in peripheral PBMC, at least with respect to the effects of leptin on cytokine expression. Despite decreased basal cytokine expression, PBMC from obese subjects retained the capacity to up-regulate cytokine expression in response to a pharmacological dose of leptin to the same degree as lean controls. Further study will determine if other aspects of immune function might be subject to leptin resistance in obesity. Our data suggest that leptin resistance is unlikely to be an active mechanism in the effects of obesity on cytokine expression in lymphocytes. Rather, PBMC from obese subjects retain responsiveness to leptin-induced cytokine expression and other, as yet unknown mechanisms lead to the observed reduced cytokine transcription in these cells in vivo.

Interpretation of these data is limited by a number of constraints. Obese subjects were older than lean subjects. In addition, lean subjects were uniformly healthy and took no medications, while obese subjects had comorbid illnesses and took medications, as outlined previously. It is possible that differences in age, comorbid diseases or medication use may affect cytokine expression in PBMC. Linear regression analysis demonstrated no association between age and cytokine expression, however, making it unlikely that age confounds these results. In addition, others demonstrate higher levels of TNF-α in older subjects [46] or alternatively, no association between ageing and serum IL-6, TNF-α or IL-1β levels [46–49], findings which are not consistent with our data if age did correlate with serum cytokine levels. Further experiments with subjects more closely matched for age and comorbidities will be necessary to address these questions. All the technical constraints of qRT–PCR analysis must be considered. We have corroborated select qRT–PCR data with an alternative endogenous gene control (β-actin). These experiments study PBMC, a heterogeneous population of numerous lymphocyte subsets. While PBMC culture allows for the study of potential paracrine interactions among lymphocytes, it provides no information regarding specific lymphocyte subsets. Study of purified lymphocyte subsets will be necessary to define alterations in specific lymphocyte compartments. Interpretation of these data is also limited by the artificial nature of the in vitro PBMC culture model used in this study. Transfer of this research into an in vivo model will provide further understanding of the clinical significance of these results. The cytokines studied were chosen because of prior data demonstrating alterations in their regulation in obesity. Other cytokines and intracellular mediators are probably involved in obesity-related alterations in immunity, and will also require study.

Conclusion

Obesity is clearly associated with alterations in immune and inflammatory function, as manifested by abnormal regulation of serum inflammatory cytokines in obese subjects [4,8,25,27–32, ]. Our data extend these observations to include cytokine expression in peripheral blood lymphocytes, and suggest that obesity-related alterations in immunity are reflected in peripheral blood lymphocyte function. Surprisingly, however, alterations in cytokine expression in PBMC are discordant with serum cytokine levels, suggesting that elevated serum levels of inflammatory cytokines in obese patients may be derived from a source other than PBMC. We hypothesize that the profoundly decreased levels of cytokine transcripts in PBMC from obese subjects may be a compensatory response to elevated systemic inflammatory cytokines elaborated by other in vivo sources.

Peripheral blood lymphocyte cytokine expression patterns probably do not fully reflect immune function in in vivo microenvironments, and further study will be required to define the relative contributions of lymphocyte subsets in different in vivo compartments to the inflammatory state in obesity. Nevertheless, these experiments demonstrate that immune dysfunction in obesity may be reflected in alterations in peripheral blood lymphocyte function. Study of this easily accessible cell population has the potential to elucidate mechanisms of altered immune function in obesity, and thus guide future research towards designing therapy to reverse such aberrations. Such therapy has the potential to treat multiple comorbidities of obesity independent of weight loss.

Acknowledgments

R. W. O. receives support from the Medical Research Foundation of Oregon, the Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons and PHS Grant 5 M01 RR000334. J. T. R. receives support from Research to Prevent Blindness and the Stan and Madelle Rosenfeld Family Trust. We thank Landon Donsbach for expert administrative assistance and manuscript preparation, and Vicki Jakovec and Susan Schenk for research coordination.

References

- 1.Calle EE, Rodriguez C, Walker-Thurmond K, Thun MJ. Overweight, obesity, and mortality from cancer in a prospectively studied cohort of U.S. adults. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1625–38. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hursting SD, Lavigne JA, Berrigan D, Perkins SN, Barrett JC. Calorie restriction, aging, and cancer prevention: mechanisms of action and applicability to humans. Annu Rev Med. 2003;54:131–52. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.54.101601.152156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Festa A, D'Agostino R, Jr, Williams K, et al. The relation of body fat mass and distribution to markers of chronic inflammation. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2001;25:1407–15. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meier CA, Bobbioni E, Gabay C, Assimacopoulos-Jeannet F, Golay A, Dayer JM. IL-1 receptor antagonist serum levels are increased in human obesity: a possible link to the resistance to leptin? J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:1184–88. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.3.8351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hanusch-Enserer U, Cauza E, Spak M, et al. Acute-phase response and immunological markers in morbid obese patients and patients following adjustable gastric banding. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2003;27:355–61. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Engeli S, Feldpausch M, Gorzelniak K, et al. Association between adiponectin and mediators of inflammation in obese women. Diabetes. 2003;52:942–7. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.4.942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bullo M, Garcia-Lorda P, Megias I, Salas-Salvado J. Systemic inflammation, adipose tissue tumor necrosis factor, and leptin expression. Obes Res. 2003;1:525–31. doi: 10.1038/oby.2003.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bastard JP, Jardel C, Bruckert E, et al. Elevated levels of interleukin 6 are reduced in serum and subcutaneous adipose tissue of obese women after weight loss. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85:3338–42. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.9.6839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liuzzo G, Goronzy JJ, Yang H, et al. Monoclonal T-cell proliferation and plaque instability in acute coronary syndromes. Circulation. 2000;101:2883–8. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.25.2883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Diehl AM. Nonalcoholic steatosis and steatohepatitis IV. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease abnormalities in macrophage function and cytokines. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2002;282:G1–5. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00384.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li Z, Lin H, Yang S, Diehl AM. Murine leptin deficiency alters Kupffer cell production of cytokines that regulate the innate immune system. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:1304–10. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.35997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stentz FB, Kitabchi AE. Activated T lymphocytes in Type 2 diabetes: implications from in vitro studies. Curr Drug Targets. 2003;4:493–503. doi: 10.2174/1389450033490966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arkan MC, Hevener AL, Greten FR, et al. IKK-beta links inflammation to obesity-induced insulin resistance. Nat Med. 2005;11:191–8. doi: 10.1038/nm1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pickup JC, Mattock MB, Chusney GD, Burt D. NIDDM as a disease of the innate immune system: association of acute-phase reactants and interleukin−6 with metabolic syndrome X. Diabetologia. 1997;40:1286–92. doi: 10.1007/s001250050822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Encinosa WE, Bernard DM, Steiner CA, Chen CC. Use and costs of bariatric surgery and prescription weight-loss medications. Health Aff (Millwood) 2005;24:1039–46. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.24.4.1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Faggioni R, Jones-Carson J, Reed DA, et al. Leptin-deficient (ob/ob) mice are protected from T cell-mediated hepatotoxicity: role of tumor necrosis factor alpha and IL-18. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:2367–72. doi: 10.1073/pnas.040561297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ozata M, Ozdemir IC, Licinio J. Human leptin deficiency caused by a missense mutation: multiple endocrine defects, decreased sympathetic tone, and immune system dysfunction indicate new targets for leptin action, greater central than peripheral resistance to the effects of leptin, and spontaneous correction of leptin-mediated defects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84:3686–95. doi: 10.1210/jcem.84.10.5999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Considine RV, Sinha MK, Heiman ML, et al. Serum immunoreactive-leptin concentrations in normal-weight and obese humans. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:292–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199602013340503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bennett BD, Solar GP, Yuan JQ, Mathias J, Thomas GR, Matthews W. A role for leptin and its cognate receptor in hematopoiesis. Curr Biol. 1996;6:1170–80. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)70684-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sanchez-Margalet V, Martin-Romero C, Gonzalez-Yanes C, et al. Leptin receptor (Ob-R) expression is induced in peripheral blood mononuclear cells by in vitro activation and in vivo in HIV-infected patients. Clin Exp Immunol. 2002;129:119–24. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2002.01900.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lord GM, Matarese G, Howard JK, Baker RJ, Bloom SR, Lechler RI. Leptin modulates the T-cell immune response and reverses starvation-induced immunosuppression. Nature. 1998;394:897–901. doi: 10.1038/29795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clement K, Viguerie N, Poitou C, et al. Weight loss regulates inflammation-related genes in white adipose tissue of obese subjects. FASEB J. 2004;18:1657–69. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2204com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Borst SE, Conover CF. High-fat diet induces increased tissue expression of TNF-alpha. Life Sci. 2005;77:2156–65. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2005.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–8. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Juge-Aubry CE, Somm E, Chicheportiche R, et al. Regulatory effects of interleukin (IL)-1, interferon-beta, and IL-4 on the production of IL-1 receptor antagonist by human adipose tissue. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:2652–8. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-031219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Somm E, Cettour-Rose P, Asensio C, et al. Interleukin-1 receptor antagonist is upregulated during diet-induced obesity and regulates insulin sensitivity in rodents. Diabetologia. 2006;49:387–93. doi: 10.1007/s00125-005-0046-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Luheshi GN, Gardner JD, Rushforth DA, Loudon AS, Rothwell NJ. Leptin actions on food intake and body temperature are mediated by IL-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:7047–52. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.12.7047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garanty-Bogacka B, Syrenicz M, Syrenicz A, Gebala A, Lulka D, Walczak M. Serum markers of inflammation and endothelial activation in children with obesity-related hypertension. Neuro Endocrinol Lett. 2005;26:242–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Park HS, Park JY, Yu R. Relationship of obesity and visceral adiposity with serum concentrations of CRP, TNF-alpha and IL-6. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2005;69:29–35. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2004.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khaodhiar L, Ling PR, Blackburn GL, Bistrian BR. Serum levels of interleukin-6 and C-reactive protein correlate with body mass index across the broad range of obesity. J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2004;28:410–15. doi: 10.1177/0148607104028006410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moon YS, Kim DH, Song DK. Serum tumor necrosis factor-alpha levels and components of the metabolic syndrome in obese adolescents. Metabolism. 2004;53:863–7. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2004.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aygun AD, Gungor S, Ustundag B, Gurgoze MK, Sen Y. Proinflammatory cytokines and leptin are increased in serum of prepubertal obese children. Mediat Inflamm. 2005;2005:180–3. doi: 10.1155/MI.2005.180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pincelli AI, Brunani A, Scacchi M, et al. The serum concentration of tumor necrosis factor alpha is not an index of growth-hormone- or obesity-induced insulin resistance. Horm Res. 2001;55:57–64. doi: 10.1159/000049971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Warnberg J, Moreno LA, Mesana MI, Marcos A. Inflammatory mediators in overweight and obese Spanish adolescents. The AVENA Study. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2004;28(Suppl. 3):S59–63. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kyzer S, Binyamini J, Chaimoff C, Fishman P. The effect of surgically induced weight reduction on the serum levels of the cytokines: interleukin-3 and tumor necrosis factor. Obes Surg. 1999;9:229–34. doi: 10.1381/096089299765553089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ciftci TU, Kokturk O, Bukan N, Bilgihan A. The relationship between serum cytokine levels with obesity and obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Cytokine. 2004;28:87–91. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2004.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Winkler G, Lakatos P, Salamon F, et al. Elevated serum TNF-alpha level as a link between endothelial dysfunction and insulin resistance in normotensive obese patients. Diabet Med. 1999;16:207–11. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.1999.00052.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pfeiffer A, Janott J, Mohlig M, et al. Circulating tumor necrosis factor alpha is elevated in male but not in female patients with type II diabetes mellitus. Horm Metab Res. 1997;29:111–14. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-979001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Arend WP, Malyak M, Guthridge CJ, Gabay C. Interleukin-1 receptor antagonist: role in biology. Annu Rev Immunol. 1998;16:27–55. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.16.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zarkesh-Esfahani H, Pockley AG, Wu Z, Hellewell PG, Weetman AP, Ross RJ. Leptin indirectly activates human neutrophils via induction of TNF-alpha. J Immunol. 2004;172:1809–14. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.3.1809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gabay C, Dreyer M, Pellegrinelli N, Chicheportiche R, Meier CA. Leptin directly induces the secretion of interleukin 1 receptor antagonist in human monocytes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:783–91. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.2.7245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Santos-Alvarez J, Goberna R, Sanchez-Margalet V. Human leptin stimulates proliferation and activation of human circulating monocytes. Cell Immunol. 1999;194:6–11. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1999.1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wisse BE, Ogimoto K, Morton GJ, et al. Physiological regulation of hypothalamic IL-1beta gene expression by leptin and glucocorticoids: implications for energy homeostasis. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2004;287:E1107–13. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00038.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Plut C, Ribiere C, Giudicelli Y, Dausse JP. Hypothalamic leptin receptor and signaling molecule expressions in cafeteria diet-fed rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;30:544–9. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.054726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Prpic V, Watson PM, Frampton IC, Sabol MA, Jezek GE, Gettys TW. Differential mechanisms and development of leptin resistance in A/J versus C57BL/6J mice during diet-induced obesity. Endocrinology. 2003;144:1155–63. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-220835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bruunsgaard H, Pedersen AN, Schroll M, Skinhoj P, Pedersen BK. TNF-alpha, leptin, and lymphocyte function in human aging. Life Sci. 2000;67:2721–31. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(00)00851-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Maes M, DeVos N, Wauters A, et al. Inflammatory markers in younger vs elderly normal volunteers and in patients with Alzheimer's disease. J Psychiatr Res. 1999;33:397–405. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3956(99)00016-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Di Iorio A, Ferrucci L, Sparvieri E, et al. Serum IL-1beta levels in health and disease: a population-based study. The InCHIANTI study. Cytokine. 2003;22:198–205. doi: 10.1016/s1043-4666(03)00152-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hasegawa Y, Sawada M, Ozaki N, Inagaki T, Suzumura A. Increased soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor levels in the serum of elderly people. Gerontology. 2000;46:185–8. doi: 10.1159/000022157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]