Abstract

Autoreactivity to heat shock protein 60 (Hsp60) has been implicated in the pathogenesis and regulation of chronic inflammation, especially in autoimmune diseases. In transplantation, there is a lack of information regarding the cytokine profile and specificity of cells that recognize self-Hsp60 as well as the kinetics of autoreactivity following transplantation. We studied the cellular reactivity of peripheral and graft-infiltrating lymphocytes against Hsp60 in renal transplant patients. Cytokine production induced by this protein in peripheral blood mononuclear cells indicated a predominance of interleukin (IL)-10 during the late post-transplantation period, mainly in response to intermediate and C-terminal peptides. Patients with chronic rejection presented reactivity to Hsp60 with a higher IL-10/interferon (IFN)-γ ratio compared to long-term clinically stable patients. Graft-infiltrating T cell lines, cocultured with antigen-presenting cells, preferentially produced IL-10 after Hsp60 stimulation. These results suggest that, besides its proinflammatory activity, autoreactivity to Hsp60 in transplantation may also have a regulatory role.

Keywords: autoimmunity, cytokines/interleukins, heat shock proteins (Hsp), renal transplantation, T cells

Introduction

Since their discovery and isolation [1,2], our view of the biological role of the highly conserved [3] heat shock proteins (Hsp) has changed from an exclusively ‘biochemical’ chaperone function [4] to an increasingly strong recognition of their interaction with the immune system involving both innate and acquired responses [5–7]. Although data in the literature suggest that the immune response to Hsp exacerbates inflammatory reactions [8], there is growing evidence that Hsp can also regulate chronic inflammation, especially in arthritis and diabetes, by inducing T lymphocytes with regulatory activity [9]. Moreover, tolerogenic Hsp60 peptides have been mapped in juvenile arthritis patients [10].

In transplantation (Tx), much of the work regarding Hsp has focused on the cytoprotective effect of these proteins, showing that their prior or early induction attenuates ischaemia and reperfusion injury [11–14]. Nevertheless, cellular response to these proteins in the context of Tx is poorly studied, especially the cytokine profile of these populations. Graft-infiltrating T lymphocytes reactive to mycobacterium Hsp65 and human Hsp70 have been detected in rats and cardiac transplant patients [15–17], and the authors suggested that this proliferative response increased rejection of allografts. On the other hand, data from an experimental model of skin allografting [18] and from our previous work [19] suggested that the cellular response to Hsp60 can also regulate the inflammatory allogeneic response. However, information on graft infiltrating T cell Hsp60 autoreactivity as well as temporal dynamics in the context of Tx is lacking. Data in the literature suggest that different regions of Hsp60 molecules may induce functionally distinct immune responses [20]. Our preliminary data suggested that Hsp60 cellular reactivity, which induced interleukin (IL)-10production, was directed mainly to the intermediate and C-terminal regions of the molecule [21].

The objective of the present work was to study more globally the cellular response cytokine profile induced by different self-Hsp60 stimuli (peptides and proteins) in renal transplant patients. We asked if autoreactivity to Hsp60 induces different cytokine patterns in the early and late period post-Tx and if this pattern is associated with the recognition of different regions of the Hsp60 molecule. We also asked if clinically distinct transplant patients (long-term stable renal function vs. chronic allograft nephropathy patients), mobilize different Hsp-reactive populations. Finally, we investigated whether graft-infiltrating lymphocytes recognize self-Hsp60 and what was the cytokine profile induced by this protein. Characterization of the cellular reactivity to Hsp60 in the context of human Tx can be used as a future alternative or complementary immunotherapy to control graft rejection.

Materials and methods

Patients and samples

A total of 45 renal transplant patients from the Hospital das Clínicas, University of São Paulo Medical School, were enrolled into this study. These patients were divided into four groups according to the biological question addressed. Group 1 comprised 14 renal transplant patients, transplanted from 1995 to 1997, studied sequentially at two time-points after Tx: early (< 6 months post-Tx; average time post-Tx = 3·4 ± 1·9 months) and late (> 1 year post-Tx; average time post-Tx = 20·2 ± 5·5 months), followed-up for 8 years. Average age at Tx was 30 ± 19 years; nine patients presented acute cellular rejection in the first 6 months post-Tx and two developed chronic allograft nephropathy. All the patients in this group received conventional triple immunosuppressive therapy with cyclosporin, azathioprine and prednisone. Group 2 (LONG) comprised 15 long-term and clinically stable renal transplant patients, transplanted from 1968 to 1975, studied at one time-point after Tx (mean time post-Tx in the sample studied = 29 ± 4 years), followed-up for 30 years after Tx. All the long-term patients presented stable renal function, measured by their current creatinine level (mean 1·0 ± 0·23 mg/dl) and clinical follow-up. The immunosuppressive therapy in this group was based on azathioprine and prednisone. Group 3 comprised 12 renal transplant patients, transplanted from 1991 to 1999, studied at one time-point, close to the diagnosis of chronic allograft nephropathy (approximately 15 days after histopathological diagnosis), and followed-up for 6 years. Mean time post-Tx in the sample studied was 3·9 ± 2·6 years. All patients in this group received triple immunosuppressive therapy with cyclosporin, azathioprine and prednisone. Group 4 comprised one patient from group 3 and four other patients from whom we received fragments of the renal biopsies, from which we derived graft-infiltrating T cell lines.

The Hospital's Committee of Ethics approved blood sample and biopsy procedures and patients gave their informed consent. Renal biopsies were performed by clinical indication and classified according to Banff criteria [22]. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were isolated by Ficoll-Hypaque gradient density centrifugation of heparinized blood samples and cryopreserved in liquid nitrogen until use.

Peptides

Peptides (20–23 mer) from different regions of Hsp60 were selected with the tepitope program, used to predict promiscuous and allele specific HLA-II restricted T cell epitopes [23,24]. Briefly, with this algorithm we screened the amino acid sequence of Hsp60 (Swissprot Accession no. P10809 [25]) and selected the regions of the molecule presenting a higher probability of binding to 25 different human leucocyte antigen d-related (HLA-DR) molecules expressed most frequently in the Caucasian population. After selecting the peptides, they were synthesized in our laboratory as described elsewhere [26]. Peptides were analysed by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry (Tof-Spec E, Micromass, Manchester, UK) and by analytical reverse-phase high profile liquid chromatography (HPLC) (Shimadzu Inc., Tokyo, Japan). We selected 18 peptides, six from N-terminal, intermediate and C-terminal regions of Hsp60. The number indicates the position of the first amino acid residue in the peptide sequence of the Hsp60 molecule: N-16 (RVLAPHLTRAYAKDVKFGAD); N-31 (KFGADARALMLQGVDLLADA); N-46 (LLADAVAVTMGPKGRTVIIE); N-76 (DGVTVAKSIDLKDKYKNIGA); N-87 (KDKYKNIGAKLVQDVANNTNEEAG); N-136 (NPVEIRRGVMLAVDAVIAEL); I-223 (YISPYFINTSKGQKCEFQDA); I-269 (KPLVIIAEDVDGEALSTLVLN); I-285 (TLVLNRLKVGLQVVAVKAPGFGD); I-321 (GGAVFGEEGLTLNLEDVQPH); I-353 (DDAMLLKGKGDKAQIEKRIQ); I-372 (QEIIEQLDVTTSEYEKEKLN); p277 (VLGGGVALLRVIPALDSLTPANED) [27]; C-449 (PALDSLTPANEDQKIGIEII); C-464 (GIEIIKRTLKIPAMTIAKNA); C-521 (PTKVVRTALLDAAGVASLLTTAE); C-539 (LTTAEVVVTEIPKEEKDPGM); C-554 (KDPGMGAMGGMGGGMGGGMF).

Proteins

Human Hsp60 gene was a gift from Dr A. C. Camargo at Butantan Institute, Brazil. The gene was removed from its original vector (pGEX-4T1, Amersham Biosciences, Uppsala, Sweden) by digestion with the restriction enzymes BamHI and NotI and cloned in His-tagged pAE vector [28]. Gene fragments corresponding to the intermediate (I-Hsp60; Hsp60 amino acid residues 195–391) and C-terminal (C-Hsp60; Hsp60 amino acid residues 392–573) regions from Hsp60 were polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-amplified using the following primers: 5′-GCGGGATCCAGAAAGGGTGTCATCACA-3′ and 5′-GCCCAAGCTTTCATGCAAGCCGTTCATTCAG-3′ for the intermediate fragment and 5′-GCGGGATCCAAACTGAATGAACGGCTT-3′ and 5′-CCGGGAGCTGCATGTGTCAGAGG-3′ for the C-terminal fragment. The PCR products were cloned directly in the pAE vector by digestion with restriction enzymes BamHI and NotI (or BamHI and HindIII for I-Hsp60) and sequenced to confirm correct cloning. For the production of recombinant proteins (Hsp60, I–Hsp60 and C–Hsp60), transformed Escherichia coli BL21 pLysS (DE3) cells were inoculated in 50 ml of 2 × YT/ampicillin/chloramphenicol medium and grown for 16 h at 37°C. The culture was then diluted in 2 × YT ampicillin/chloramphenicol medium to ABS600nm = 0·1. The culture was grown at 37°C until ABS600nm reached 0·8. At this point, isopropylthio-beta-d-galactoside (IPTG) (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) was added to a final concentration of 1·2 mM and incubated for an additional 2 h. After induction, the culture was centrifuged and the bacterial pellet was ressuspended in 90 ml Tris–NaCl buffer (Tris 100 mM, pH 8·0, NaCl 300 mM) plus 5 mM immidazole (Merck, NJ, USA). The cells were disrupted in a French press (Thermospectronic, Waltham, MA, USA) and centrifuged in order to ascertain whether the recombinant protein was present in the soluble or insoluble fraction (inclusion bodies). Hsp60 was purified from the soluble fraction while the fragments I–Hsp60 and C–Hsp60 were purified from the insoluble fraction in denaturating conditions (all the buffers with 8 M urea). The proteins were purified in a Ni+2-charged Sepharose column (Chelating Sepharose Fast Flow; Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden). After loading the soluble or insoluble fraction, the columns were washed with 10 vol Tris–NaCl buffer plus 30 mM immidazole and the proteins eluted with Tris–NaCl buffer plus 800 mM immidazole. One-ml fractions were collected and analysed in sodium dodecyl sulphate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS–PAGE). For the fragments I–Hsp60 and C–Hsp60, protein refolding was achieved by dialysis against decreasing urea concentrations in PBS at 4°C for 2 days followed by extensive dialysis against PBS alone. The remaining insoluble material was removed by centrifugation. The control protein calglandulin [29] was expressed and purified under the same conditions as Hsp60, and the plasmid was a kind gift from Dr Inácio Junqueira de Azevedo from Butantan Institute (São Paulo, Brazil). Quantification of protein was performed by bicinchoninic acid (BCA) kit assay (Pierce Biotechnology Inc, Rockford, IL, USA). Contaminant lipopolysacharide (LPS) was removed using Triton X-114, as described previously [30]. Quantification of endotoxin contamination in protein preparations was performed with the Limulus amoebocyte lysate (LAL) assay (QCL−1000; BioWhittaker Cambrex Inc, Walkerville, MD, USA). The endotoxin concentrations in our proteins were < 10 EU/mg of protein. Hsp60 was analysed by Western blotting (anti-Hsp60, catalogue no. SPA-806; Stressgen, Victoria, Canada).

PBMC cytokine enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

PBMC (5 × 105 PBMC/well) were resuspended in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Sigma) supplemented with 10% inactivated pooled human serum, plated in 96-well round-bottomed plates (Falcon) and incubated with or without stimuli at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere and 95% humidity for 48 h. The antigens used were: Hsp60 peptides (5 µm, approximately 10 µg/ml), recombinant proteins Hsp60, I-Hsp60, C-Hsp60 and control protein calglandulin (10 µg/ml) and phytohaemagglutinin (PHA, 2·5 µg/ml; Sigma) as positive control. After the incubation period, the plates were centrifuged and the supernatant collected and tested for interferon (IFN)-γ, IL-10, IL-4 and transforming growth factor (TGF)-β by sandwich ELISA. Antibodies and standards for IFN-γ were from Endogen (Woburn, MA, USA), for IL-10 and IL-4 were from Pharmingen (San Jose, CA, USA) and for TGF-β were from R&D (Minneapolis, MN, USA). Briefly, 96-well plates (Easy Wash; Costar, Cambridge, MA, USA) were coated with capture anti-cytokine antibodies diluted in carbonate-bicarbonate buffer (Na2CO3 15 mm, NaHCO3 35 mm, pH 9·6) and incubated overnight at 4°C. After washing with PBS containing 0·05% Tween 20 (Sigma) and blocking with PBS-0·5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) for IFN-γ, IL-10 and IL-4 or with PBS 5% saccharose, 5% Tween 20, 0·05% sodium azide (for TGF-β), for 2 h at room temperature, the plates were incubated with supernatant samples and standards in duplicate overnight at 4°C. Biotinylated secondary antibody specific for each cytokine was added and, after 45 min incubation, avidin–peroxidase was added for 30 min at room temperature. Standards, biotinylated antibodies and avidin–peroxidase were diluted in dilution buffer (PBS 0·1% BSA for IFN-γ, IL-10 and IL-4 or PBS 1·4% delipidized bovine serum, 0·05% Tween 20 for TGF-β). The assays were developed with o-phenylenediamine (OPD; Sigma) for IFN-γ, IL-4 and IL-10 and absorbance was measured at 490 nm using the microplate ELISA reader (model 1550; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). TGF-β assays were developed with substrate reagent patch (R&D; catalogue no. DY999) and absorbance was measured at 450 nm using the microplate ELISA reader. Analysis was performed using the Microplate Manager 4·0 software (Bio-Rad), based on a standard concentration curve. Cytokine production was considered positive over the detection limit of each cytokine: 40 pg/ml for IL-10 and IL-4 and 17 pg/ml for IFN-γ and TGF-β. Cytokine production induced by different stimuli was considered as the concentration above the spontaneous production of cells alone, without antigen.

Graft-infiltrating T cell lines

Graft-infiltrating T cell lines (GIL) were established based on a protocol described in the literature [31] and standardized in our laboratory [32]. Renal biopsy fragments from five different renal transplant patients were dissociated mechanically and the micro fragments were placed into 96-well culture plates in the presence of 1 × 105 irradiated (5000 rad) autologous PBMC/well in DMEM supplemented with 10% inactivated pooled human serum plus IL-2 (40 U/ml; Sigma). The plates were maintained at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere and 95% humidity for 14–20 days. To further expand the graft-infiltrating T cells, the cells were stimulated with autologous irradiated PBMC and PHA (2·5 µg/ml) under the same culture conditions described above. For the flow cytometry analysis, T cell populations 10–14 days after the last stimulation were stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated anti-human CD4 and CD25 and phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated anti-human CD8, CD4, CD28 and CD25 monoclonal antibodies and mouse isotype controls (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) for 30 min at 4°C and washed twice in PBS containing 2% fetal calf serum and 0·1% sodium azide. Five to 10 thousand events gated for lymphocytes were acquired and analysed in the fluorescence activated cell sorter (FACS)Calibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA).

Cytokine detection of graft-infiltrating T cell lines

Ten to 14 days after the last stimulation, T cell lines (5 × 105/well) were incubated with autologous irradiated PBMC (5 × 105/well) as antigen-presenting cells, plus the different antigens. The antigens used were: some Hsp60 peptides (5 µM, approximately 10 µg/ml), recombinant proteins Hsp60, I-Hsp60, C-Hsp60 and control protein calglandulin (10 µg/ml) and PHA (2·5 µg/ml; Sigma) as positive control. After 48 h of stimulation, culture supernatants were collected and the cytokines IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-10, tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α and IFN-γ were measured with Th1/Th2 cytometric bead array (CBA) kit (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA, USA), following the manufacturer's instructions. Acquisition and analysis were performed in a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). TGF-β was measured by sandwich ELISA, as described above for the PBMC. Cytokine production was considered positive over the detection limit of each cytokine: 17 pg/ml for TGF-β and 10 pg/ml for the other cytokines tested by CBA. Cytokine production induced by different stimuli was considered positive when the concentration exceeded the production by T cell lines plus autologous PBMC, without antigen. We also measured the spontaneous production of T cell lines alone (without antigen and without autologous PBMC).

Statistical analysis

The Mann–Whitney U-test (two-tailed) was used to compare the levels of cytokines between groups, Fisher's exact test was used to evaluate the association between data and Wilcoxon's signed-rank test was used to compare cytokine production in the early and late periods post-Tx. All statistical analyses were performed using prism version 3·0 and spss version 10·0·1.

Results

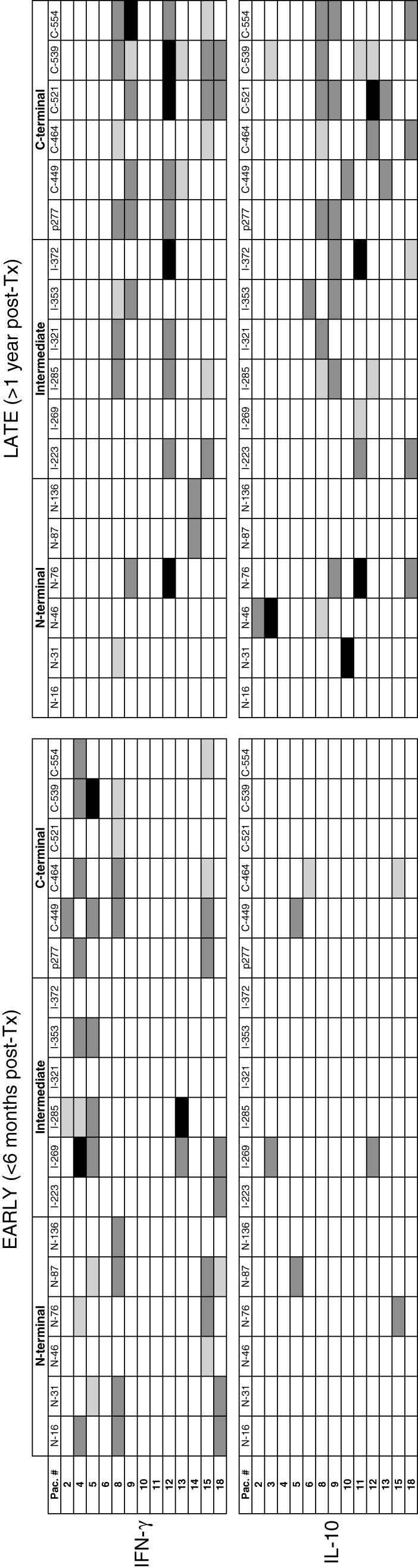

Increased IL-10 production induced by Hsp60 peptides in the late period post-Tx – multiple epitopes in the intermediate and C-terminal region of the protein

We observed a dominant response to Hsp60 peptides in this group of renal transplant patients. Regardless of the period post-Tx, 10 of 13 patients produced IFN-γ induced by Hsp60 peptides and 12 of 13 produced IL-10 (Fig. 1). We detected IFN-γ production both in the early and late periods post-Tx, induced by Hsp60 peptides from the three regions of the molecule. In contrast, IL-10 was poorly produced in the early period (five of 13 patients, each subject recognizing one to two peptides) followed by an increase of this potentially anti-inflammatory cytokine in the late period post-Tx. IL-10 was detected more frequently in the late period post-Tx, mainly in response to C-Hsp60 peptides (P = 0·05). Ten of 13 patients produced IL-10 in the late period post-Tx and half these subjects recognized multiple peptides (≥ 3) from the intermediate and C-terminal regions of the molecule (Fig. 1). The response to PHA was the same in both periods post-Tx (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

Cytokine production induced by heat shock protein (Hsp)60 peptides in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) of renal transplant patients in the early (< 6 months) and late (> 1 year) periods post-transplantation. PBMC were cultured in the presence of Hsp60 peptides derived from the N-terminal, intermediate and C-terminal region of the molecule. The number indicates the position of the first amino acid residue in the peptide sequence of the Hsp60 molecule. After 48 h, the supernatant was collected and the cytokines interferon (IFN)-γ and interleukin (IL)-10 were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Levels of cytokines induced by Hsp60 peptides are represented as □ (no production);  (1–9 pg/ml); ▪ (10–99 pg/ml); ▪ (100–500 pg/ml).

(1–9 pg/ml); ▪ (10–99 pg/ml); ▪ (100–500 pg/ml).

Response to Hsp60 in clinically stable long-term and chronic allograft nephropathy patients (patient groups 2 and 3)

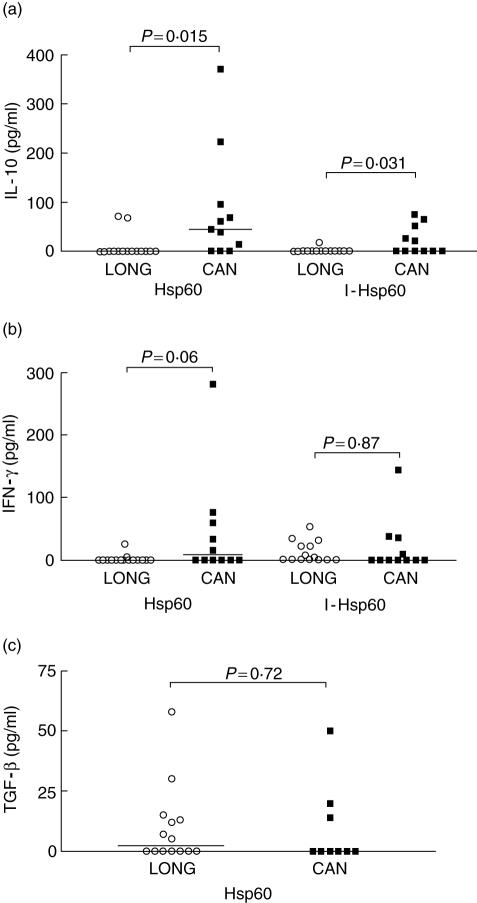

In order to answer the question as to whether renal transplant patients with contrasting clinical outcomes mobilize functionally different Hsp60-reactive cells we compared the cytokine production induced by Hsp60 in long-term clinically stable patients (LONG, group 2) and recently diagnosed chronic allograft nephropathy patients (CAN, group 3). In contrast to what we were expecting initially, Hsp60 and the intermediate fragment I-Hsp60 induced more IL-10 in the CAN than in the LONG group (P = 0·015 and P = 0·031, respectively; Fig. 2a). IFN-γ induced by Hsp60 was also higher in the CAN group, although with no statistically significant difference (Fig. 2b). In contrast, both CAN and LONG patients produced IFN-γ in response to I-Hsp60 (Fig. 2b). The production of TGF-β after stimulation with Hsp60 was observed both in the CAN and LONG group, while we observed a slight increase in levels of this cytokine in the LONG group (Fig. 2c). In order to evaluate the IL-10/IFN-γ balance in both groups, we calculated the IL-10 : IFN-γ ratio. PBMC from CAN patients presented a higher IL-10 : IFN-γ ratio induced by Hsp60 and I-Hsp60, in contrast to LONG patients (Table 1). We also calculated the individual IL-10 : IFN-γ ratios and compared these ratios between the LONG and CAN groups. CAN patients presented statistically significant higher IL-10 : IFN-γ ratios, induced by Hsp60, compared to LONG patients (P = 0·03, Mann–Whitney U-test; data not shown).

Fig. 2.

Cytokine production induced by heat shock protein (Hsp)60 in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) of renal transplant patients with different clinical outcomes: clinically stable long-term patients (group 2, LONG: ○, mean 29 years after transplantation, n = 15) and recently diagnosed chronic allograft nephropathy patients (group 3, CAN: ▪, n = 12). PBMC were cultured in the presence of recombinant proteins Hsp60 and its intermediate (I-Hsp60; residues 195–391). After 48 h, the supernatants were collected and the cytokines interleukin (IL)-10 (a), interferon (IFN)-γ (b), transforming growth factor (TGF)-β (c) and IL-4 were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. IL-4 was not detected in these two groups of patients. P-values calculated by Mann–Whitney U-test, two-tailed.

Table 1.

Interleukin (IL)-10: interferon (IFN)-γ ratio of clinically stable long-term (LONG) and chronic allograft nephropathy (CAN) renal transplant patients.

| LONG | CAN | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL-10 | IFN-γ | Ratio | IL-10 | IFN-γ | Ratio | |

| Hsp60 | 0·5 (0–0) | 0·5 (0–0) | 1 | 44·9 (7–159) | 7·8 (0–68) | 5·8 |

| I-Hsp60 | 0·5 (0–0) | 0·5 (0–26) | 1 | 1·9 (0–58) | 0·5 (0–37) | 3·8 |

| PHA | 140 (0–182) | 2000* | 0·07 | 316 (0–664) | 2000* | 0·16 |

IL-10 and IFN-γ-values are represented by median (interquartile range) cytokine production of the group; ratios were calculated by dividing median IL-10 production by median IFN-γ production of each group. Values of 0 were replaced by 0·5 to allow calculation of ratios.

All values were over detection limit (> 2000 pg/ml). Hsp: heat shock protein; I-Hsp60: intermediate Hsp60 fragment, residues 195 to 391; PHA: phytohaemagglutinin.

GIL recognize self-Hsp60 (patient group 4)

To study whether the response against Hsp60 observed in the periphery is also present in the kidney, where the immune reaction against the graft is effectively occurring, we analysed the capacity of GIL to recognize Hsp60 and the pattern of cytokine produced in response to different Hsp60 stimuli. We established and expanded GIL from biopsies of five different renal transplant patients: three diagnosed as acute rejection, one normal and one CAN (Table 2). We observed a predominance of CD8+ T cells in three GIL; one was exclusively CD4+ and the other presented the same amount of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (Table 2). All the GIL produced IFN-γ spontaneously and only one produced IL-4 (data not shown). We did not observe spontaneous production of TNF-α, IL-10, IL-5, IL-2 or TGF-β in these GIL.

Table 2.

Graft-infiltrating T cell lines derived from renal transplant patients' biopsies: phenotype and histopathological diagnosis.

| % Positive cells | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GIL (no.) | Diagnosis | Time post-Tx | CD4+ | CD8+ | CD4+/CD25+ | CD8+/CD25+ | CD4+/CD28+ | CD8+/CD28+ | CD8+/CD28– |

| 49 | CAN | 6 years | 9 | 83 | 9 | 83 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| 57 | AR | 12 days | 18 | 67 | 18 | 56 | 16 | 15 | 52 |

| 58 | AR | 2 months | 21 | 77 | 19 | 57 | 21 | 17 | 60 |

| 60 | AR | 7 days | 48 | 52 | 48 | 52 | 31 | 16 | 36 |

| 59 | Normal | 3 month | 99 | 0 | 73 | 0 | 97 | 0 | 0 |

AR: acute rejection; CAN: chronic allograft nephropathy; GIL: graft-infiltrating lymphocytes derived from biopsies from five different renal transplant patients; n.d. not determined.

We observed a mixed cytokine production induced by different Hsp60 stimuli, with IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-10 and IL-2 positive responses (Table 3). No IL-4, IL-5 or TGF-β production was observed in co-cultures with GIL after incubation with Hsp60 (peptides and/or proteins). The intermediate recombinant fragment I-Hsp60 induced exclusively IL-10 in three of five GIL cultures, while the control irrelevant protein induced a very low amount of this cytokine in only one GIL (Table 3). The GIL derived from the CAN-diagnosed biopsy presented the most widespread response to Hsp60 peptides and proteins (Table 3, patient 49). The GIL derived from patient 58, diagnosed with acute rejection, produced only IL-10 in response to Hsp60 proteins and a high amount of this cytokine in response to one N-terminal peptide (Table 3).

Table 3.

Cytokine production induced by heat shock protein (Hsp)60 in graft-infiltrating T cell lines (GIL) derived from renal transplant patients' biopsies.

| GIL (no.)/biopsy diagnosis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 49: CAN | 57: AR | 58: AR | 6: AR | 59: normal | |

| IFN-γ (pg/ml) | |||||

| N-87 | 21 | – | – | – | – |

| N-136 | 12 | – | – | – | – |

| I-353 | 3 | – | – | – | – |

| I-372 | 7 | – | – | – | 12 |

| p277 | – | – | – | – | – |

| I-Hsp60 | – | – | – | – | – |

| C-Hsp60 | 12 | – | – | – | – |

| Hsp60 | 4 | – | – | – | – |

| Cal | 20 | – | – | – | – |

| PHA | 2230 | > 5000 | 4413 | 1186 | 2780 |

| TNF-α (pg/ml) | |||||

| N-87 | 59 | – | – | – | – |

| N-136 | – | – | – | – | – |

| I-353 | 8 | – | – | – | 5 |

| I-372 | 84 | – | – | – | – |

| p277 | – | – | – | – | – |

| I-Hsp60 | – | – | – | – | – |

| C-Hsp60 | – | 10 | – | – | – |

| Hsp60 | 30 | – | – | – | 8 |

| Cal | 34 | – | – | – | – |

| PHA | – | > 5000 | – | 78 | 1362 |

| IL-10 (pg/ml) | |||||

| N-87 | – | – | 564 | – | – |

| N-136 | – | – | – | – | – |

| I-353 | 6 | – | – | – | – |

| I-372 | – | – | – | – | – |

| p277 | – | – | – | – | – |

| I-Hsp60 | 5 | 19 | 226 | – | – |

| C-Hsp60 | 7 | 33 | 15 | – | – |

| Hsp60 | 23 | 3 | 113 | – | – |

| Cal | – | – | 1 | – | – |

| PHA | – | 25 | 17 | – | – |

Levels of cytokines after the incubation of GIL with autologous peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) as antigen-presenting cells and different Hsp60 stimuli (peptides and proteins) over the production of the condition without antigen. After 48 h, the supernatant was collected and the cytokines tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α, interferon (IFN)-γ, interleukin (IL)-10, IL-5, IL-4 and IL-2 were detected by cytometric bead array and transforming growth factor (TGF)-β by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Cal: control irrelevant protein. IL-5, IL-4 and TGF-β were not detected. IL-2 was detected only in GIL 57 in response to N-136 peptide and PHA and in GIL 60 in response to PHA. CAN: chronic allograft nephropathy; AR: acute rejection. For the peptides, the number indicates the position of the first amino acid residue in the peptide sequence of the Hsp60 molecule. I-Hsp60: intermediate Hsp60 fragment, residues 195–391; C-Hsp60: C-terminal Hsp60 fragment, residues 392–573).

Discussion

The results from this study showed the existence of Hsp60 autoreactive mononuclear cells, both in the periphery and in cells infiltrating the graft in renal transplant patients. These cells produced both inflammatory and regulatory cytokines in response to this self-antigen, even though we observed IL-10 predominance in the late period post-Tx. IL-10 was also predominant in the chronic allograft rejection patients and in graft-infiltrating T cell lines reactive to the Hsp60 recombinant intermediate fragment. Considering that IL-10 is mainly an immunosuppressive cytokine [33], our data could indicate a regulatory role for Hsp60 autoreactivity, as also suggested by others [34,35].

We were unable to map, using this experimental approach, a peptide that induced exclusively one cytokine and/or was only recognized by clinically stable patients or those with rejection. In fact, we observed a diversity of responses to Hsp60 peptides in all groups of patients studied, which could be explained at least partly by the different HLA that the patients display.

In the current study, we observed temporal differences in IL-10 production induced by Hsp60 peptides, with a major production in the late period post-Tx which was induced preferentially by intermediate and C-terminal peptides. This is in accordance with the hypothesis raised in our previous study, that autoreactivity to Hsp60 could be predominantly regulatory at the late point post-Tx [19], and also in accordance with the ‘regulatory diversification’ mechanism proposed in experimental arthritis [20]. The authors showed that diversification of the T cell responses towards carboxyterminal determinants of the Hsp60 was related to resolution of the inflammatory process [20], and that the transfer of cells from animals immunized with peptides from the C-terminal region of Hsp60 blocked the development of arthritis [7].

Our results regarding graft-infiltrating T cell lines suggest that Hsp60-reactive T lymphocytes can also participate in the regulation of the inflammatory response with mainly IL-10 production. This result is in agreement with recent findings, in which Hsp60 stimulated IL-10 production in T cells, up-regulating the expression of Th2-associated transcription factor GATA3 and down-regulating T-bet and nuclear factor (NF)-κB proinflammatory transcription factors [36]. Because we observed a predominance of CD8+ T cells in these graft-infiltrating T cell lines, CD8 Tc1 and Tc2 could also contribute to the observed cytokine profiles [37]. T cell lines derived from patients 57 and 58, which produced IL-10 in response to Hsp60 stimuli, presented a high percentage of CD8+CD28– T lymphocytes, one of the subpopulations of T regulatory (Treg) cells described in the context of alloreactivity [38]. Graft-infiltrating T lymphocytes reactive to Mycobacterium Hsp65 and to human Hsp70 have been reported previously using proliferation analysis [15–17], and the authors considered that these cells were increasing the inflammatory response. As the cytokine profile of these Hsp-reactive cells was not described, one cannot exclude the possibility that they may also have a regulatory function.

Regarding the cellular response to Hsp60 in two clinically distinct groups, chronic rejection and clinically stable long-term patients, it was interesting to observe that although IFN-γ production induced by Hsp60 was higher in CAN patients, this cytokine did not significantly differentiate these two opposing clinical outcomes. In contrast, we found a higher IL-10 : IFN-γ ratio in chronic allograft nephropathy patients compared to long-term patients, indicating a shift towards a Th2 dominance in response to Hsp60 in CAN patients. One possible explanation is that the intense inflammation that culminated in chronic rejection increased the expression of Hsp60 and consequently immunoregulatory mechanisms mediated by Hsp through IL-10 production. Although this regulatory response was not sufficient to prevent the progression to chronic rejection, it was likely to be one of the regulatory mechanisms that participated in this immunological response. Recently, it was found that patients with active oligoarticular juvenile arthritis produced more IL-10 induced by Hsp60 peptides than patients with disease remission and healthy controls [10]. Even though the comparison between LONG and CAN patients may be biased because of the differences in immunosuppressive therapy and time post-Tx in these groups, we showed important differences in the cellular response to Hsp60 in these patients with contrasting clinical outcomes.

The precise role of IL-10 induced by Hsp60 autoreactivity in Tx is yet to be clarified. We cannot exclude that IL-10 induced by Hsp60 is also playing a pathogenic role, as this cytokine has been implicated in increased infiltration of CD8+ T cells to the graft, the production of alloantibodies and the expression of co-stimulatory molecules [39–41]. On the other hand, IL-10 could be produced by Treg cells reactive to Hsp, as reported by others [9,42]. These authors suggested that, by different mechanisms including mucosal tolerance, Treg cells reactive to Hsp60 are generated and participate in the regulation of inflammatory processes through bystander suppressive effects, such as through the production of IL-10 or other suppressive cytokines [42]. In addition, IL-10 can also be produced by monocytes through direct TLR activation. We are currently addressing the question of which cells are producing IL-10, using intracellular cytokine staining.

The results from the current work add more information regarding the boundary between autoreactivity and Tx that has been explored by other groups. The cellular and humoral responses to self-antigens, such as myosin, vimentin and collagen-V, have been associated mainly with allograft rejection, based on findings that show that immunization with these self-antigens [43,44] or transfer of autoreactive T cells [45,46] accelerates rejection. Vimentin-specific CD8+ T cells, which produce IFN-γ, were detected in cardiac transplant patients [47]. In these settings, autoreactivity after Tx is considered pathological. On the other hand, one cannot discard the possibility that part of the autoimmune response in the context of Tx can also down-modulate inflammation, depending on the graft milieu [48]. In addition, Haque et al.[45] showed that not all the collagen-V reactive T cells are able to induce lung allograft rejection, and they suggested that collagen-V may have antigenic and potentially tolerogenic peptides [49]. Moreover, we have recently been able to significantly prolong heart allograft survival in mice instilled intranasally with a human Hsp60 derived peptide (in preparation).

We believe that discriminating which Hsp epitopes and under which contexts these proteins may induce differential function activities will help us to use their immunoregulatory properties for future clinical applications, either alone or in combination with other immunosuppressive therapies, to prevent allograft rejection.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr A. C. Camargo for kindly providing the human Hsp60 gene, Dr Inácio Junqueira de Azevedo for kindly providing the calglandulin plasmid and for help and technical advice on the expression and purification of recombinant proteins, Lilian Jesus de Oliveira for technical help, Washington Robert da Silva and Cláudio Roberto Püschel for peptide synthesis, Benedita Vitoria Messias for collecting patients' blood samples, Dr Kellen Faé, Dr Kamal Moudgil and Dr Angelina Bilate for fruitful discussions and Linda Caldas for English corrections to the manuscript. Dr Cristina Caldas attended the PhD programme in Immunology at the Instituto de Ciências Biomédicas of the University of São Paulo and was supported by a scholarship from Fapesp (2000/12599–4). This work was supported by grants from Fapesp (2002/06495–7) and CNPq, Brazil.

References

- 1.Ritossa F. New puffing pattern induced by temperature shock and dnp in Drosophila. Experientia. 1962;18:571. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tissières A, Mitchell HK, Tracy UM. Protein synthesis in salivary glands of Drosophila melanogaster: relation to chromosome puffs. J Mol Biol. 1974;84:389–98. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(74)90447-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brocchieri L, Karlin S. Conservation among HSP60 sequences in relation to structure, function, and evolution. Protein Sci. 2000;9:476–86. doi: 10.1110/ps.9.3.476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hartl FU. Molecular chaperones in cellular protein folding. Nature. 1996;381:571–9. doi: 10.1038/381571a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blachere NE, Li ZH, Chandawarkar RY, et al. Heat shock protein-peptide complexes, reconstituted in vitro, elicit peptide-specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte response and tumor immunity. J Exp Med. 1997;186:1315–22. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.8.1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Binder RJ, Vatner R, Srivastava P. The heat-shock protein receptors: some answers and more questions. Tissue Antigens. 2004;64:442–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.2004.00299.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Durai M, Gupta RS, Moudgil KD. The T cells specific for the carboxyl-terminal determinants of self (rat) heat-shock protein 65 escape tolerance induction and are involved in regulation of autoimmune arthritis. J Immunol. 2004;172:2795–802. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.5.2795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mia MY, Durai M, Kim HR, Moudgil KD. Heat shock protein 65-reactive T cells are involved in the pathogenesis of non-antigenic dimethyl dioctadecyl ammonium bromide-induced arthritis. J Immunol. 2005;175:219–27. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.1.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Eden W, van der Zee R, Prakken B. Heat-shock proteins induce T-cell regulation of chronic inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:318–30. doi: 10.1038/nri1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kamphuis S, Kuis W, de Jager W, et al. Tolerogenic immune responses to novel T-cell epitopes from heat-shock protein 60 in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Lancet. 2005;366:50–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66827-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Katori M, Tamaki T, Takahashi T, Tanaka M, Kawamura A, Kakita A. Prior induction of heat shock proteins by a nitric oxide donor attenuates cardiac ischemia/reperfusion injury in the rat. Transplantation. 2000;69:2530–7. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200006270-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Redaelli CA, Tien YH, Kubulus D, Mazzucchelli L, Schilling MK, Wagner AC. Hyperthermia preconditioning induces renal heat shock protein expression, improves cold ischemia tolerance, kidney graft function and survival in rats. Nephron. 2002;90:489–97. doi: 10.1159/000054739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wagner M, Cadetg P, Ruf R, Mazzucchelli L, Ferrari P, Redaelli CA. Heme oxygenase-1 attenuates ischemia/reperfusion-induced apoptosis and improves survival in rat renal allografts. Kidney Int. 2003;63:1564–73. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00897.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Patel A, van de Poll MC, Greve JW, et al. Early stress protein gene expression in a human model of ischemic preconditioning. Transplantation. 2004;78:1479–87. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000144182.27897.1e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moliterno R, Valdivia L, Pan F, Duquesnoy RJ. Heat shock protein reactivity of lymphocytes isolated from heterotopic rat cardiac allografts. Transplantation. 1995;59:598–604. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moliterno R, Woan M, Bentlejewski C, et al. Heat shock protein-induced T-lymphocyte propagation from endomyocardial biopsies in heart transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 1995;14:329–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Trieb K, Grubeck-Loebenstein B, Eberl T, Margreiter R. T cells from rejected human kidney allografts respond to heat shock protein 72. Transpl Immunol. 1996;4:43–5. doi: 10.1016/s0966-3274(96)80032-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Birk OS, Gur SL, Elias D, et al. The 60-kDa heat shock protein modulates allograft rejection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:5159–63. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.9.5159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Granja C, Moliterno RA, Ferreira MS, Fonseca JA, Kalil J, Coelho V. T-cell autoreactivity to Hsp in human transplantation may involve both proinflammatory and regulatory functions. Hum Immunol. 2004;65:124–34. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2003.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moudgil KD, Chang TT, Eradat H, et al. Diversification of T cell responses to carboxy-terminal determinants within the 65-kD heat-shock protein is involved in regulation of autoimmune arthritis. J Exp Med. 1997;185:1307–16. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.7.1307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Caldas C, Spadafora-Ferreira M, Fonseca JA, et al. T-cell response to self HSP60 peptides in renal transplant recipients: a regulatory role? Transplant Proc. 2004;36:833–5. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2004.04.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Racusen LC, Solez K, Colvin RB, et al. The Banff 97 working classification of renal allograft pathology. Kidney Int. 1999;55:713–23. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.00299.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bian H, Reidhaar-Olson JF, Hammer J. The use of bioinformatics for identifying class II-restricted T-cell epitopes. Methods. 2003;29:299–309. doi: 10.1016/s1046-2023(02)00352-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sturniolo T, Bono E, Ding J, et al. Generation of tissue-specific and promiscuous HLA ligand databases using DNA microarrays and virtual HLA class II matrices. Nat Biotechnol. 1999;17:555–61. doi: 10.1038/9858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jindal S, Dudani AK, Singh B, Harley CB, Gupta RS. Primary structure of a human mitochondrial protein homologous to the bacterial and plant chaperonins and to the 65-kilodalton mycobacterial antigen. Mol Cell Biol. 1989;9:2279–83. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.5.2279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Iwai LK, Juliano MA, Juliano L, Kalil J, Cunha-Neto E. T-cell molecular mimicry in Chagas disease: identification and partial structural analysis of multiple cross-reactive epitopes between Trypanosoma cruzi B13 and cardiac myosin heavy chain. J Autoimmun. 2005;24:111–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2005.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Raz I, Elias D, Avron A, Tamir M, Metzger M, Cohen IR. Beta-cell function in new-onset type 1 diabetes and immunomodulation with a heat-shock protein peptide (DiaPep277): a randomised, double-blind, phase II trial. Lancet. 2001;358:1749–53. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06801-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ramos CR, Abreu PA, Nascimento AL, Ho PL. A high-copy T7 Escherichia coli expression vector for the production of recombinant proteins with a minimal N-terminal His-tagged fusion peptide. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2004;37:1103–9. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2004000800001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Junqueira-de-Azevedo IL, Pertinhez T, Spisni A, Carreno FR, Farah CS, Ho PL. Cloning and expression of calglandulin, a new EF-hand protein from the venom glands of Bothrops insularis snake in E. Coli Biochim Biophys Acta. 2003;1648:90–8. doi: 10.1016/s1570-9639(03)00111-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aida Y, Pabst MJ. Removal of endotoxin from protein solutions by phase separation using Triton X-114. J Immunol Meth. 1990;132:191–5. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(90)90029-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weber T, Kaufman C, Zeevi A, et al. Propagation of lymphocytes from human heart transplant biopsies: methodological considerations. Transplant Proc. 1988;20:176–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Coelho V, Moliterno R, Higuchi ML, et al. Gamma delta T cells play no major role in human heart allograft rejection. Transplantation. 1995;60:980–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen S, Kapturczak MK, Wasserfall C, et al. Interleukin 10 attenuates neointimal proliferation and inflammation in aortic allografts by a heme oxygenase-dependent pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:7251–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502407102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pockley AG. Heat shock proteins, anti-heat shock protein reactivity and allograft rejection. Transplantation. 2001;71:1503–7. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200106150-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pockley AG, Muthana M. Heat shock proteins and allograft rejection. Contrib Nephrol. 2005;148:122–34. doi: 10.1159/000086057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zanin-Zhorov A, Tal G, Shivtiel S, et al. O. Heat shock protein 60 activates cytokine-associated negative regulator suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 in T cells: effects on signaling, chemotaxis, and inflammation. J Immunol. 2005;175:276–85. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.1.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Woodland DL, Dutton RW. Heterogeneity Cd4 (+) Cd8 (+) T Cells Curr Opin Immunol. 2003;15:336–42. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(03)00037-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sindhi R, Manavalan JS, Magill A, Suciu-Foca N, Zeevi A. Reduced immunosuppression in pediatric liver–intestine transplant recipients with CD8+CD28– T-suppressor cells. Hum Immunol. 2005;66:252–7. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2004.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li W, Fu F, Lu L, et al. Systemic administration of anti-interleukin-10 antibody prolongs organ allograft survival in normal and presensitized recipients. Transplantation. 1998;66:1587–96. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199812270-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Furukawa Y, Becker G, Stinn JL, Shimizu K, Libby P, Mitchell RN. Interleukin-10 (IL-10) augments allograft arterial disease. paradoxical effects of IL-10 in vivo. Am J Pathol. 1999;155:1929–39. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65512-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.el Gamel A, Grant S, Yonan N, et al. Interleukin-10 and cellular rejection following cardiac transplantation. Transplant Proc. 1998;30:2387–8. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(98)00663-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.van Eden W, Koets A, van Kooten P, Prakken B, van der Zee R. Immunopotentiating heat shock proteins: negotiators between innate danger and control of autoimmunity. Vaccine. 2003;21:897–901. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(02)00538-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fedoseyeva EV, Zhang F, Orr PL, Levin D, Buncke HJ, Benichou G. De novo autoimmunity to cardiac myosin after heart transplantation and its contribution to the rejection process. J Immunol. 1999;162:6836–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nair S, McCormack A, Holder A, et al. Immunisation with vimentin causes rejection of syngeneic cardiac grafts. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2004;23:S132. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Haque MA, Mizobuchi T, Yasufuku K, et al. Evidence for immune responses to a self-antigen in lung transplantation: role of type V collagen-specific T cells in the pathogenesis of lung allograft rejection. J Immunol. 2002;169:1542–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.3.1542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yoshida S, Haque A, Mizobuchi T, et al. Anti-type V collagen lymphocytes that express IL-17 and IL-23 induce rejection pathology in fresh and well-healed lung transplants. Am J Transplant. 2006;6:724–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01236.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Barber LD, Whitelegg A, Madrigal JA, Banner NR, Rose ML. Detection of vimentin-specific autoreactive CD8+ T cells in cardiac transplant patients. Transplantation. 2004;77:1604–9. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000129068.03900.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fedoseyeva EV, Kishimoto K, Rolls HK, et al. Modulation of tissue-specific immune response to cardiac myosin can prolong survival of allogeneic heart transplants. J Immunol. 2002;169:1168–74. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.3.1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sumpter TL, Wilkes DS. Role of autoimmunity in organ allograft rejection: a focus on immunity to type V collagen in the pathogenesis of lung transplant rejection. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2004;286:L1129–39. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00330.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]